Chapter Twenty-Four. The Missing Muse

There is no way to know for certain when the creative spark will strike. Yet as with carrying a lightning rod in a storm, there are ways to increase the odds. As we’ve seen throughout this book, showing up and working hard can make a huge difference. As Coleman Cox said, “The harder I work the luckier I get.” And I say that the harder you work, the more creative you become. Effort and creativity are closely intertwined.

The celebrated American painter and photographer Chuck Close put it this way: “The advice I like to give young artists, or really anybody who’ll listen to me, is not to wait around for inspiration. Inspiration is for amateurs; the rest of us just show up and get to work.” And this isn’t just a flippant, off-the-cuff remark. Chuck Close was tragically paralyzed over twenty years ago, yet as an artist he continues to thrive.

Hard Work Isn’t Enough

The idea that creative inspiration strikes when we put in the time and effort is a strong theme throughout this book. Yet that isn’t the only way. Creative inspiration is complex, and it doesn’t always come like a lightning bolt from the sky; sometimes it arrives like a quiet voice that comes to you while floating in the middle of the sea. Inspiration is as unpredictable as the waves. Regardless, inspiration does ignite most often when we begin the work, yet sometimes all the tenacity, grit, and self-discipline in the world aren’t enough to pave the way for inspiration to appear.

A few years ago, I began to think more and more about what it means to live the creative life. I filled countless pages in my journals with ideas, sketches, and quotes. The creative juices flowed in an effortless and exciting way. Then a small light bulb went off in my head: What if these ideas could turn into a book? My enthusiasm swelled. I began to imagine how the project might evolve. I put together a proposal and after a few revisions sent it off with high hopes.

Ideals Are Easy

My excitement was off the charts when I received the good news—my book proposal was approved. I took a deep breath and triumphantly raised my fist into the air. I was proud and it was time to begin. Without any hesitation, I began by journaling a few thoughts. I quickly wrote about the type of book that I wanted to write. I began with an ideal. Here’s what I wrote: “I want to write about the adventure and reward of the creative life. I want to write something that stands the test of time. Simple, uncluttered and true. A guiding force. A magnetic north. A reference book. A survival guide. I want to write a book that is authentic and alive. I want to write something that is without veneer. I want to write something that will help people live more creative and meaningful lives. I want to write a book that will bring change. I want to write with steel strong words with carbon fiber ink. I want to write a book that I can be proud of, one that I can display and evangelize without a second thought.” I wrote and wrote, the words gushing forth in an uninhibited flow. With the vision cast, now it was time for the real writing to begin. I cleared my schedule for the following day, left for home, and my confidence soared.

The next day I walked into my studio with a victorious stride, saying aloud, “This book is going to write itself.” Little did I know that I was going to have to eat my words. With a book title like The Creative Fight, how could I have been so naive? I sat down to write and suddenly all of my momentum disappeared. The gush turned into a slog. The once bright creative spark became dull. Instead of enthusiasm, I was full of dread. I tried to write, but the words came out like chatter and noise. The sentences read like empty platitudes and worn-out clichés. I felt like an imposter—no, I was an imposter. Self-doubt stiffened my joints. Days turned into weeks and weeks, and I still hadn’t written a single usable word.

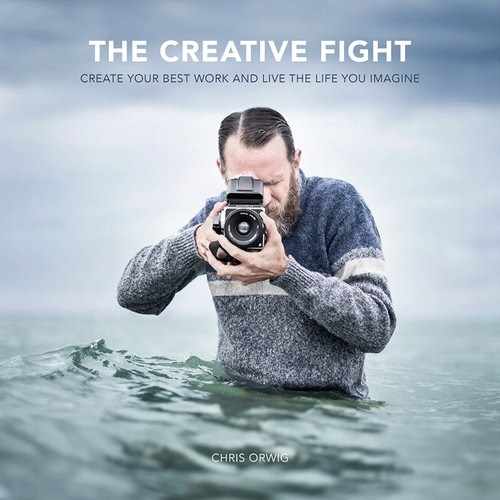

Picasso said, “Inspiration exists, but it has to find you working.” Picasso must have lied, because I was working but inspiration never found my door. Or maybe it was my fault? Maybe I was working in the wrong way, like showing up for a boat trip but arriving at the wrong dock. Maybe inspiration was waiting for me somewhere else. I felt adrift, unequipped, and in over my head, like a tourist who stood in a sailboat for a photograph but was suddenly blown out to sea. I was out of my element and ill prepared. The immensity of the situation made me feel like a small speck on the endless sea.

The Visitation

Floating alone in the vast ocean, I was lost, inspiration nowhere in sight. But then, as if I had been visited by a muse, Steve Callahan’s plight came to mind. During a solo transatlantic race, Callahan’s sailboat struck an unidentified object and sank off the coast of Africa. In the darkness of night he escaped with a small life raft and a duffel bag of supplies. Stranded and alone, he drifted across the Atlantic Ocean for 76 days. It was a miracle he survived. Yet it was on this voyage that he came to know himself and become the most alive. Callahan later reflected, “To my mind, voyaging through wildernesses, be they full of woods or waves, is essential to the growth and maturity of the human spirit. It is in the wilderness that you really learn who you are.”

It was as if a muse wanted me to revisit Callahan’s story to give me insight into my own. It became clear that my problem was not about talent or skill but about identity and control. I had been trying to subdue and wrestle the ideas of the book, when what I needed most was to get lost in the wilderness in order to grow. Rather than work on the book, I needed the book to work on me.

Before I could make progress, I needed to abandon the extra baggage I had unknowingly brought along. After doing this, I then realized I was out of fuel. I was depleted and couldn’t figure out why. The muse spoke and reminded me that the energy needed to prepare for a voyage is different from the energy needed to set sail. And a voice whispered, When your ship sinks (as it inevitably will), you have to stay calm.

Adrift

Alone in my life raft, I had been nervous and scared. Worse, I didn’t want my weakness to show. So I acted like I had it all together, stood up, and pounded on my chest, but the ocean didn’t seem to care. Defeated, I crumpled up at the base of the raft. I felt so small. The muse brought more of Callahan’s words to mind: “The heartfelt realization of one’s insignificance yields a calming sense of being completely connected to a greater whole.” Like a key that opened a lock, smallness and isolation gave way to connection and grace. I realized my mistake. After my book project was approved, the creative spark vanished because I was trying to write from a posture of conquest and strength. This type of book could only be written as one who was adrift on the sea—for it is from a position of weakness that you find strength.

WHY DO WE LOVE THE SEA? IT IS BECAUSE IT HAS SOME POTENT POWER TO MAKE US THINK THE THINGS WE LIKE TO THINK.

— ROBERT HENRI

Creativity flourishes most when we stop pretending. And creativity always prefers honesty over show. It became clear that this project couldn’t be about making myself look talented or smart. And it couldn’t be written with the ending in mind; this book was a journey into the unknown. Like most worthwhile creative endeavors, it was a risk and the possibility of failure was real.

When we are stuck, working harder can help, but it can also make the problem worse. At first glance, this may sound contradictory to the basic premise of this book. Yet the creative fight isn’t just about climbing the ladder, but making sure that you have found the right one. Letting go of ego and admitting that creative inspiration isn’t always something that we can generate ourselves is a surefire way to speed up the search for the ladder you were destined to climb.

Many Muses

The ancient Greeks were a culture inspired. Collectively, their creative output wasn’t just a spark; it was a blaze. Yet the Greeks believed that inspiration came not from within, but from an outside source. For the Greeks, the epicenter of inspiration was not the individual but a muse. The ancient myths told of nine muse goddesses who provided inspiration for literature, science, and the arts. These nine daughters of Zeus fueled the fire.

Thousands of years later, the ideas and myths surrounding the muse have evolved. In modern times, we have traded in the limited and ethereal archetype muse for a more ubiquitous form. Today, a muse might be a musician who inspires us to sing, a mountain that motivates us to paint, or the flight of a bird that inspires us to get out of our locked cage. Muses take on countless shapes and forms. Some are predictable, like the calm ocean at dusk, whereas others go unseen, like the feeling you get when you climb up a tree.

I once climbed to the top of an ancient redwood. Out of breath and tired from climbing, I clung to the now-small tree trunk that fit inside my two hands. Hundreds of feet below, the fifteen-foot-wide trunk was anchored to the ground. Swaying in that treetop, I felt that I was in a sacred space. I took a deep breath and drank in the pine scent, clouds, and light. Up in the tree, I felt on top of the world, as if I could almost touch the heavens above. My soul took flight. It was a surreal and spiritually refreshing experience to be perched so far off the ground.

Thin Places and Myth

The ancient Celts might say my experience was divine. Celtic mythology considers some places—including trees—thresholds or doorways to the divine. Such places are called “thin” because they occur when the visible and the invisible worlds practically touch.

As one traditional Celtic saying explains, “Heaven and earth are only three feet apart, but in the thin places that distance is even smaller.” Thin places are often associated with wild landscapes, mountaintops, rivers, and oceans. What makes a place thin isn’t so much the geography as the experience there. As poet Sharlande Sledge wrote, “Thin places are where the door between this world and the next is cracked open for a moment, and the light is not all on the other side.”

The concept of “thin places” is an old and beautiful one. When I get stuck or just feeling dull, I visit places that make me feel refreshed and clear my head. This experience doesn’t always include a spiritual glow, but sometimes it does. My favorite place to go is an ancient redwood grove. And I love to walk to the water’s edge, whether on the sand or at the end of a pier. Or I like to get lost on the mountain biking trails behind my house. The refreshment of nature restores my hope and belief, belief that my situation can improve. This faith acts like kindling that keeps the creative fire aglow.

Thin places aren’t limited to epic landscapes and mountaintops. You can create a thin space in various ways. When I’m stuck somewhere that isn’t ideal, I find that closing my eyes and taking a few deep breaths can help. Other ideas include lighting a candle or using a Tibetan meditation singing bowl. Rather than do something different every time, be consistent so that the peace and refreshment can more readily flow. Try it for yourself, even now. Pause reading. Close your eyes and take a breath with the idea of seeing your space as thin.

STEP 1. CREATE AN ENERGY MAP

Creative progress isn’t easy; it requires different types of energy at each stage:

Stage 1. Energy to plan

Stage 2. Energy to execute

Stage 3. Energy to recover when you fall

Stage 4. Energy to finish strong

For an upcoming project, goal, or dream, create a map that clarifies the three types of energy that you will need. Mapping this out can serve as a reminder to shift gears as you transition, and it can act as a guide to help you maintain the right type of energy for the task at hand. In your journal, write out a few characteristics of the type of energy. For example:

1. Plan = excitement, imagination, inhibition

2. Execute = grit, tenacity, steadfast strength

3. Recover = calm, patient

STEP 2. CREATE YOUR OWN MUSE

Myths spark the imagination. The Greek myths told of nine muses for different domains (poetry, dance, comedy, song, and so on). The muses had names, personalities, and skills. The ancient poets, dancers, and other creatives turned to a muse for help.

As a way to modernize this concept, write a myth of your own. The simplest definition of a myth is a story with meaning attached to it. Write a myth that describes five muses of your own—consider selecting muses that are people who inspire you to live in a better way. This might be an author, a musician, a pastor, a poet, a friend, or a comedian of international fame.

STEP 3. DEFINE THIN PLACES

Thin places are sacred and special places that open you up to the divine. Select a few thin places that inspire you. Consider finding thin places in your town, city, state, country, and world. In your journal, write out a list of five, and then visit one of these in search of the divine.