2. The Two-Generation Model

If you’ve ever watched three people playing racquetball, you know how chaotic it is. Two-person racquetball is pretty straightforward: Person A hits the ball, then Person B, and then back and forth until someone scores. With three people, though, Person A is playing against Persons B and C—at least while serving. Then, when Person B serves, A and C team up, and later it’ll be A and B against C. As you might imagine, the games are generally longer than two-person racquetball games because it’s a little harder to score when you’re always facing two opponents. And if you were to come in during the middle of a point, it would be fairly difficult to figure out which player had served.

This leads to an interesting observation (at least to me). While I can think of plenty of individual sports where we compete against multiple opponents—racquetball, track, and auto racing come to mind—I can’t think of a single team sport that involves more than two teams competing against one another. We have individual sports where one person can defeat any number of opponents by being faster, stronger, or more skilled. We also have team sports like gymnastics where multiple teams are competing, but they’re not truly competing against each other because they’re not actively interacting; instead, each team participates separately and does not interfere in any way with the performance of the other competitors. But can you imagine how complicated football would be if there were three end zones? Each offense could score in two different end zones, but they’d have to get through two different defenses as well. Can you even envision a triangular basketball court? Games would end with final scores of 3–1, and players would retire at 25 because they’d all be nearly dead from exhaustion.

And do you know why we don’t have these kinds of competitions? It’s not because their creation is beyond us. We’ve made buildings that rotate in the wind, we’ve got 943 varieties of mustard when the world would happily have survived with merely 65, and anyone who has ever tried to make a turducken (which is a chicken stuffed into a duck and then stuffed into a turkey, in case you’re not from Minnesota) knows that there is definitely an easier way to get all that meat shoved into your face. We could invent sports with 3 or 4 or 12 teams competing simultaneously. We could design the proper courts and stadiums, and we could figure out a system of universally acceptable rules. It would be complicated, but we could certainly do it.

But we haven’t, we won’t, and the reason we won’t is because it isn’t natural. In human history, we’ve never come up with a team sport where more than two teams at a time compete directly against one another because it has never occurred to us to do so. It’s always two teams. It’s the only way we know how to think about those kinds of competitions.

And...Your Point?

The point is that the current generational divisions we’re operating with are similarly unnatural. It’s virtually impossible not to feel overwhelmed when you feel as though you’re simultaneously playing against three distinct generations. The current conversation doesn’t simply complicate the issue; it actually goes against human nature.

If that sounds extreme to you, then consider that except for the seasons of the year, we divide almost nothing into fours. Our body is bilaterally symmetrical and consists of organs and sections that never occur more than twice: two eyes, two ears, two hands, two knees, two kidneys, two lungs, two nostrils, and two halves of the brain. Human beings have created hundreds of political parties over the centuries, but all of them boil down into two major categories: conservative or liberal (relative to their counterparts).1 Returning to the sports analogy, those of us who enjoy a given sport typically support only one team and reserve a special hatred for one other team more than all others. There are two biological sexes, two states of energy in the binary system that’s allowing me to write this sentence,2 two possible locations in which you might spend eternity after you die, and two types of transmissions you can choose from when you buy a new car.

1 And just in case you’re a Green Party American or Free Democratic Party German and want to contest the nuances of our multifaceted political system, you can either vote or not vote on any given issue, and if you choose to vote, you can either vote Yes or No. Fundamentally, all of politics is the exercise of one of only two options. Yay for simplicity!

2 I am so not getting into the swamp of quantum computing, since I think it’s safe to say that generational issues don’t have much of a quantum component. But in case I wanted to, I would argue that in a quantum system, you know either the position or the velocity. Boom!

Indeed, in virtually everything we do, we divide the world into twos. Men vs. Women, Republicans vs. Democrats, Axis vs. Allies (and then later East vs. West), American League vs. National League, Paper vs. Plastic, East Coast Rap vs. West Coast Rap, Ketchup vs. Mustard,3 Pepsi vs. Coke, Introverts vs. Extroverts, Rural vs. Urban, PC vs. Mac, Nerds vs. Jocks...as you can see, we have an overwhelming tendency to divide the world into two groups. We do so because it feels natural and allows us to simplify what might otherwise be a chaotic and indecipherable mess.

3 Not quite sure why this one is such a contest since they taste totally different. But get yourself into the right online forums, and you’ll soon learn that there are millions of people apparently willing to die in support of their chosen condiment.

Your conversation about generational issues at work shouldn’t be any different. Dividing people into four generations has deprived us of the ability to provide a workable contrast against those who do things differently. By creating a situation in which every person has three supposed antagonists, current generational theory has essentially rendered all of us paralyzed, unable to know how to move forward against so many different people coming at us from so many different directions.

In fact, a simple look at today’s workplace demographics is yet another reason the four-generation model is an obsolete one. First off, the so-called Traditionalists constitute around 5% of today’s current workforce, which is a small enough percentage that it simply doesn’t make sense to view them as a population so idiosyncratic and distinct from your other workers that they need to be coached and listened to and managed in a completely different way from everyone else. Then we have approximately 75 million Baby Boomers, 35 to 40 million in Generation X, and 75 to 80 million in Generation Y. From a purely mathematical standpoint, you can easily see that two generations are dominating the workforce.

Moreover, Gen Xers tend to view themselves as a composite of the larger cohorts they’re sandwiched between. They identify themselves as having some of the typical characteristics of Baby Boomers and some of the Millennials. So really, they’re already trying to help simplify this picture for us by voluntarily placing themselves in one of the two larger camps.

Alan’s experience is typical of many Gen Xers and, as mentioned a moment ago, provides a nice transition into the model I’m advocating in this book. To put things into a perspective we can actually work with, we need to create a functional dichotomy. That’s what Alan did naturally; instead of thinking of himself as a member of a distinct generation who had nothing in common with those older or younger than himself, he identified sometimes with one group and sometimes with another.

We need to get rid of these four generations. We don’t need them. To be perfectly honest, we don’t even actually use them, at least not when we’re comparing ourselves against others (more on that in a few pages). So let’s replace it with something simpler and more natural. As we’ve already discussed, everything we do ultimately gets divided into two main opposing groups. And when you dissect the generational divide to its most fundamental level, there are really only two ways we look at one another.

There’s Generation Us, and then there’s Generation Them.

Generation Us and Generation Them

Throughout the entirety of human history, we’ve always divided the world into these two simple categories: Us and Them.4 Us and Them is how we think about everyone and everything. We have friends and family, and everyone else is a stranger; we have people who are the same color or sexual orientation or religion as ourselves, and everyone else is not; we have people who work in our industry and people who work in other fields; we have people who work in our company, and everyone else is an outsider who can’t possibly understand the issues we’re dealing with or the processes that govern our business.

4 I realize that I mentioned this once in the Introduction, but I’m mentioning it here again because there’s a decent chance you didn’t bother to read the Introduction.

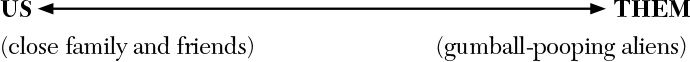

Because we are constantly analyzing everyone with multiple Us/Them criteria, we tend to unconsciously put everyone we meet along a sliding spectrum of Us and Them—a single straight line, with Us at one end and Them at the other:

Most of us have very few people we would place all the way at the Us side of the line. Your spouse, your kids, your parents, your siblings, your closest friends—these people are probably as far on the Us side of things as anyone gets.

On the other hand, most of us have a larger (but still small) number of people who we would place all the way on the Them side: people from different countries who speak a different language, practice a different religion, eat different foods, wear different clothes (or no clothes at all), and engage in different pastimes. I’m sure you can think of some people or cultures that seem so foreign that it’s hard to imagine having anything at all in common with them. Three-headed aliens that eat rocks and poop out gumballs, for instance, would probably be all the way to the right.

At its most basic level, this constant analysis of Us and Them governs the way we treat the people with whom we come in contact. The more we can identify Us qualities in others, the better we tend to get along; the more we identify Them qualities in others, the more we respond with hesitation, confusion, suspicion, contempt, derision, or outright hatred.

The entire history of human civilization can be viewed through this extremely simple lens. When one tribe or nation finds enough common qualities between itself and another, the two groups form trade agreements, establish military alliances, and occasionally merge into a single unified people. This is the process by which the American colonies, which did not initially function as a cohesive whole, were able to unify and oppose the British. America’s original colonies disagreed on a wide variety of issues, but ultimately they chose to view one another as predominantly Us and the British as predominantly Them. The rest, of course, is history.

Similarly, when one company finds another in a similar industry with a similar vision and qualities complementary to their own, the two often begin to work together and occasionally merge. When we find someone we have a lot in common with, we become friends and sometimes marry. The history of female suffrage, civil rights, and same-sex marriage in the United States can all be explained by the slow but steady progression of a greater number of Americans viewing all three of those groups of people as more Us and less Them.

At the same time, when we realize that we no longer have very many qualities in common—when we start to see our spouses or bosses or business partners or military allies as more Them and less Us—that’s when we start to separate. That’s when we stop talking, get divorced, feel stifled or unappreciated at work, set up trade embargoes, and so on. I challenge you to find a single human interaction in which the constant interplay of Us and Them is not at work. It is the philosophical underpinning of absolutely everything we do. The more we see other people like Us, the better we get along. The more we see other people like Them, the more problems we have.

Your generational issues at work are functioning in exactly the same way. If you’re butting heads with someone and have attributed the difficulty to generational issues, the real problem is that you feel as though your antagonist is more Them and less Us. When you and a same-age colleague commiserate about the chronic impatience of your young employees or lament the hopeless intransigence of the old guard, what you’re really doing is identifying Us qualities in your conversation partner and Them qualities in the people you’re complaining about. It’s that simple.

Fortunately, this classification of Us and Them isn’t a rigid or permanent one. Because each of us is constantly analyzing everyone else as Us or Them in dozens of different ways all the time, our attitudes about other people tend to shift considerably. A Christian will be friendlier toward a Muslim she works with than one who lives in a foreign country because the two coworkers have several Us qualities in common—same employer, similar job duties, possibly even similar interests—but she is likely to become less friendly toward a Christian friend who suddenly converts to Islam because that act moves the friend more into the Them camp. If you learn tomorrow that you and your boss share the same hobby, you’ll view her in a slightly more positive light; if you learn that the two of you share 17 hobbies in common, you’ll probably get along very well. If one of your friends suddenly goes on a nine-month diet comprised entirely of pickles and hummus, your relationship with that person will change in a slightly negative direction—especially if he doesn’t let you give him a mint.

The goal of all this, presuming that you want to have happy and healthy relationships with the people you’re forced to share the world with, is to put as many people as possible into the Us camp. And there are exactly two ways we do this (there’s that number two again).

The first is to find as many commonalities as possible between ourselves and everyone else. Shared interests, shared heritage, shared goals—the more of these we find in others, the better we’ll get along. To modify an earlier example, when a family with a different religion than yours ends up moving into the house next door, they’re already more of an Us than they would be if they lived halfway around the world because you can easily identify specific things you have in common—similar income level, kids in the same school system, and so on.

However, finding those commonalities isn’t always possible. Not everyone has the same background or education or hobbies as you, and you can’t force other people to think or behave exactly the way you do. So the second way we attempt to move people into the Us camp is to try to understand why they act or believe the way they do because doing so allows us to put other people’s behaviors and attitudes into a context we can better understand. Understanding where someone else is coming from is rarely as strong a unifier as going to the same college or being diagnosed with the same type of cancer, but it’s still a powerful tool to turn Them into Us. To modify another earlier example: If you are heterosexual but see the push for same-sex marriage as a desire on the part of same-sex couples to enjoy the same kinds of relationships as heterosexual couples, you will be more likely to support them because you’ll recognize an Us quality in them—namely, the desire to marry.

So far we’ve limited our discussion to social and cultural issues—race, religion, sexual orientation, nation-building, war, and so on. I’ve done this to illustrate that the Us/Them dichotomy is the defining psychological impulse behind everything we do. We’re hard-wired to put everyone we meet into one of these two categories, and we move them closer toward fully Us or fully Them depending on a lot of different factors. The more commonalities we can find between ourselves and others and the better we can understand their motivations for doing whatever it is that they do, the more we’ll view them as Us and the better we’ll be able to work together. It’s not a terribly complicated concept, and it works for everything. These are the only two ways that any of us ever come together.

So now that we’ve established a philosophical framework for solving every type of human problem (presuming, you know, that people actually want to do that), let’s focus on how the Us vs. Them dynamic plays out in your professional life.

Us vs. Them, the Professional Version

Just like in our personal and cultural lives, the Us and Them dynamic plays out in every element of our professional lives as well. Management vs. employees, salaried workers vs. contractors, the people in your department vs. the people in any other department, and so on. Regardless of where you work, you will have certainly witnessed one or more of these dichotomies. All other things being equal, managers tend to align themselves more closely with other managers than with entry-level employees, and salaried workers tend to view outside consultants as more Them and less Us.

In an ideal company, everyone identifies everyone else as an Us. Managers, employees, customers, and shareholders all view themselves as part of a single entity with a shared and mutually beneficial goal. That’s when you see a happy and productive workforce, healthy competition between departments, and all the other “we’re in this together” stuff that helps companies grow and profit and make the Best Companies to Work For list and so on. If you look at the mission statement of Starbucks, for example, you’ll see a dedicated effort to position everyone in their enterprise as united in purpose, from the farmers who grow their coffee to the baristas who use delicious syrups to make that coffee palatable to the shareholders who demand constant growth. Whether Starbucks is succeeding or not can be a matter of debate, but there can be no debate that their goal is to create a company where everyone is an Us.

In a crappy5 company, however, workers tend to treat the people outside of their immediate circle as Them. That’s when you hear employees complaining about management, customers jumping ship for a more attentive competitor, departments separating off into isolated and occasionally antagonistic silos, and so on. To use an easy example, the management at Enron treated both their customers and their employees as Them, and that attitude contributed to a self-centered culture that ultimately led to that company’s collapse. More recently, the senior management at Polaroid treated digital media in general and its users in particular as something to be avoided rather than embraced—as a Them rather than Us—and in 2008 Polaroid filed for bankruptcy.

5 I felt like crappy was a better antonym for ideal than less than ideal.

So if you’re a CEO trying to figure out how to improve your company’s culture, the first question you need to be asking is, “What can I be doing to create an environment where everyone is an Us?” If you’re a sales manager struggling to improve relations with the people who create the products you’re responsible for selling, you need to ask, “What can I do to convince our designers and developers that my goals are the same as theirs?” And if you’re a new employee eager to move up in your company, you need to ask, “What can I do to persuade my managers that I’m really one of them?”

Viewing the world through an Us/Them framework, and then constantly thinking about how to move people away from Them and toward Us, is the easiest way to define problems and find solutions for every human issue we face—personal, professional, or otherwise.

How the Us/Them Dynamic Operates

We’ve discussed how the Us/Them argument plays out in the workplace in several different ways. And without question, far and away the biggest Us/Them dichotomy that we deal with in our professional lives is the cultural and intellectual divide between more-experienced workers and their less-experienced colleagues. It’s a split that transcends departmental divisions and supersedes even management/staff divisions. Employees can become managers, but new managers are almost never immediately accepted as full equals by their more senior counterparts. In the same way, workers in different departments who were hired at the same time will often find more in common with each other than they will with their younger or older colleagues in their own departments.

In fact, when we talk about generational issues in the workplace, what we’re often talking about are issues of experience rather than age. We usually phrase the issue as a function of age, since getting older and gaining experience are typically synonymous. But not always.

Case in point: If you’re hiring 2 entry-level account executives, or 200 entry-level call center representatives, or 2,000 entry-level computer software engineers, their age is absolutely irrelevant to the way you will train them. Whether you’re talking about an 18-year-old high school graduate, a 25-year-old college graduate, a 40-year-old making a midcareer transfer from another industry, or a 52-year-old returning to the workforce after spending the last two decades raising her children, they’ll all go through the same training. They’ll all be given the same tools. And, most importantly, they’ll all be viewed as inexperienced by your existing workforce.

That doesn’t mean age isn’t an issue because it absolutely is. In each of these examples, your older workforce will typically discover more Us qualities with your older hires, just as your younger staff members will connect more easily with your younger hires. The point is that age isn’t the only factor at play here because there are some important ways in which age and experience are not always synonymous. We talk about this in more detail in later chapters, but for now it’s important to note that this issue of experience—how we acquire it, what it teaches us, how we use it, and how it occasionally constrains and even harms our ability to innovate—is going to be a major part of our discussion.

Interestingly enough, there’s almost no research to help us determine at what point a person moves from inexperienced to experienced at a given job or skill. Some studies have attempted to quantify the point at which a person becomes an expert at a given skill, and we reference those later; but there’s really nothing to help explain at what point the novice transforms into the knowledgeable and respected dispenser of wisdom. For the most part, you’ve been left to determine that for yourself—which is something all of us instinctively do, but unfortunately we are rarely in perfect agreement with everyone else’s definitions of experienced and inexperienced. What exactly constitutes “more experienced” and “less experienced” varies from industry to industry and company to company.

The “more experienced/less experienced” dichotomy is also one whose members tend not to move very quickly along the Us/Them line. If someone has 12 more years’ experience as a carpenter or computer analyst or whale herder than you do, there’s really nothing you can do to catch up. Until he retires or switches industries, he’ll always have 12 more years’ experience than you, and so he’ll always be inclined to view you as less-experienced and therefore at least a little Them.

And if this dichotomy of age and experience isn’t a perfect rule, it’s absolutely true that the vast majority of us feel as though it is. In my capacity as a keynote speaker, I’ve spoken at hundreds of different events—association conferences, company meetings, leadership retreats, all-staff training days, and everything in between. Collectively I’ve had the opportunity to speak to representatives of several thousand different companies, everything from mother/daughter businesses to Fortune 25 companies. And whenever the subject of generational issues has come up, all of the people and companies I’ve spoken to—repeat, 100% of them—have told me that their workplace feels as though there are a lot of workers in the more-experienced camp (however they choose to define that for themselves), a lot of workers in the less-experienced (or inexperienced) camp, and relatively few people in between to bridge that gap. This belief simultaneously reflects the hard numbers of current workplace demographics and reinforces the main thesis of this book that all of us instinctively want to divide things into two opposing sides for the sake of clarity and simplicity. And I’m willing to bet anything—a speedboat, a pet giraffe, whatever you want—that if I were to ask you if it feels as though you have a large number of highly skilled workers, a large number of new or less-skilled workers, and not enough people in between to create a smooth transition between the two, you’d say yes.

The point is, if yours is the typical workforce, then the “more experienced/less experienced” dichotomy is probably impacting every element of your business. It’s a dichotomy that’s both rooted in natural demographics and reinforced by our natural tendency to divide things into twos. That’s why the four-generation model has to go, and that’s why replacing it with a more natural two-generation approach—one that focuses specifically and relentlessly on the constant interplay between age and experience—will make the solutions to your generational issues easier than they’ve ever been before.

And to make things even easier (and more amusing), let’s change the terms a little bit. So far I’ve been focusing on the terms more experienced and less experienced, but that’s a little wordy and not a whole lot of fun to say. More importantly, most of the time age and experience go hand in hand. So let’s call it what it really is. Every generational book you’ve ever read and every generational training session or keynote speech you’ve ever attended has danced around the truth in an effort to play nice and be polite and do all that stuff I don’t really feel like doing anymore. So let’s just come out with the truth.

The real generational issue facing your company is the endless battle between Young People and Old People.

If you’re truly honest with yourself, that’s how you frame generational differences at work. Your issues are unique to you and your particular situation. But whatever those issues are, you have never said to yourself, “Well, I’m a Baby Boomer with Traditionalist tendencies trying to understand the subtle nuances of Gen X and Gen Y sensibilities.” You’ve never thought, “I’m a skeptical, self-starting Gen Xer struggling to deal with the entrenched hierarchical mentality of my Boomer superiors.” Ever. In the history of ever, nobody has phrased their generation difficulties in those terms.

What you’ve really thought is:

“That punk kid doesn’t have the first idea how things really work around here.”

“That stodgy old windbag should just do us all a favor and retire.”

These two sentences encapsulate everything you’ve ever thought when it comes to generational issues at work. You’ve had one or both of these thoughts because that’s what human beings have been thinking about other human beings since we became civilized enough to get mad at each other. There are not four generations in the workplace, and there never havebeen. There are two—Young People and Old People.

You will not always be the Young Person or the Old Person in the conflict. I’m sure you’ve had issues with colleagues who are both more and less experienced than you are. I’m sure you’ve rolled your eyes at people who have been with your company forever, just like I’m certain you’ve muttered curses to yourself at people who got hired two months ago. However, whenever you butt heads with someone at work and chalk it up to a generational issue, you always and automatically position yourself as either Young or Old relative to the person you’re having a problem with.

So we’ve finally eliminated our current, unwieldy four-generation model and replaced it with a two-generation model, Young People vs. Old People. This makes sense. Now it’s time to start solving 100% of your generational issues at work. If you’ll remember, that means we have to do two things: First, find as many things as possible that Young People and Old People have in common; and second, explain as well as possible why each generation thinks and behaves the way it does. The answers to both of those questions are fairly simple, and those conversations will overlap from time to time.

But before we do that, let’s have a little fun.