Chapter Three. Visualization and Sketching

Objectives

After studying the material in this chapter, you should be able to:

1. Define the terms vertex, edge, plane, surface, and solid.

2. Identify four types of surfaces.

3. Identify five regular solids.

4. Draw points, lines, angled lines, arcs, circles, and ellipses.

5. Apply techniques that aid in creating legible well-proportioned freehand sketches.

6. Apply techniques to draw irregular curves.

7. Create a single-view sketch.

8. Create an oblique sketch.

9. Create perspective sketches.

10. Create an isometric sketch of an object.

Refer to the following standard:

• ANSI/ASME Y14.3 Orthographic and Pictorial Views

Complex Surface Models Created Using 3D CAD (Courtesy of Professor Richard Palais, University of California, Irvine, and Luc Benard.)

Understanding Solid Objects

Sketches and drawings are used to communicate or record ideas about the shape of 3D objects. Before starting to sketch, it helps to develop a vocabulary for understanding and discussing 3D shapes.

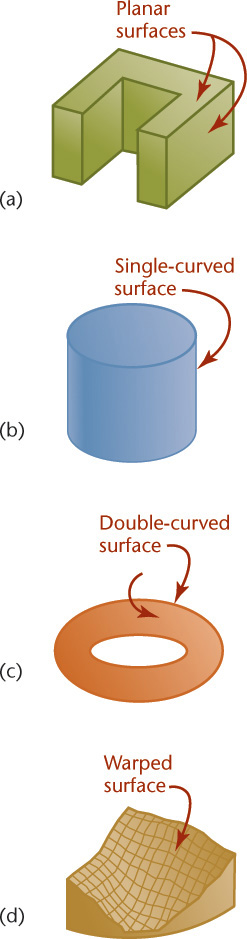

Three-dimensional figures are referred to as solids. Solids are bounded by the surfaces that contain them. These surfaces can be one of the following four types:

• Planar

• Warped

Regardless of how complex a solid may be, it is composed of combinations of these basic types of surfaces. Figure 3.1 shows examples of the four basic types of surfaces.

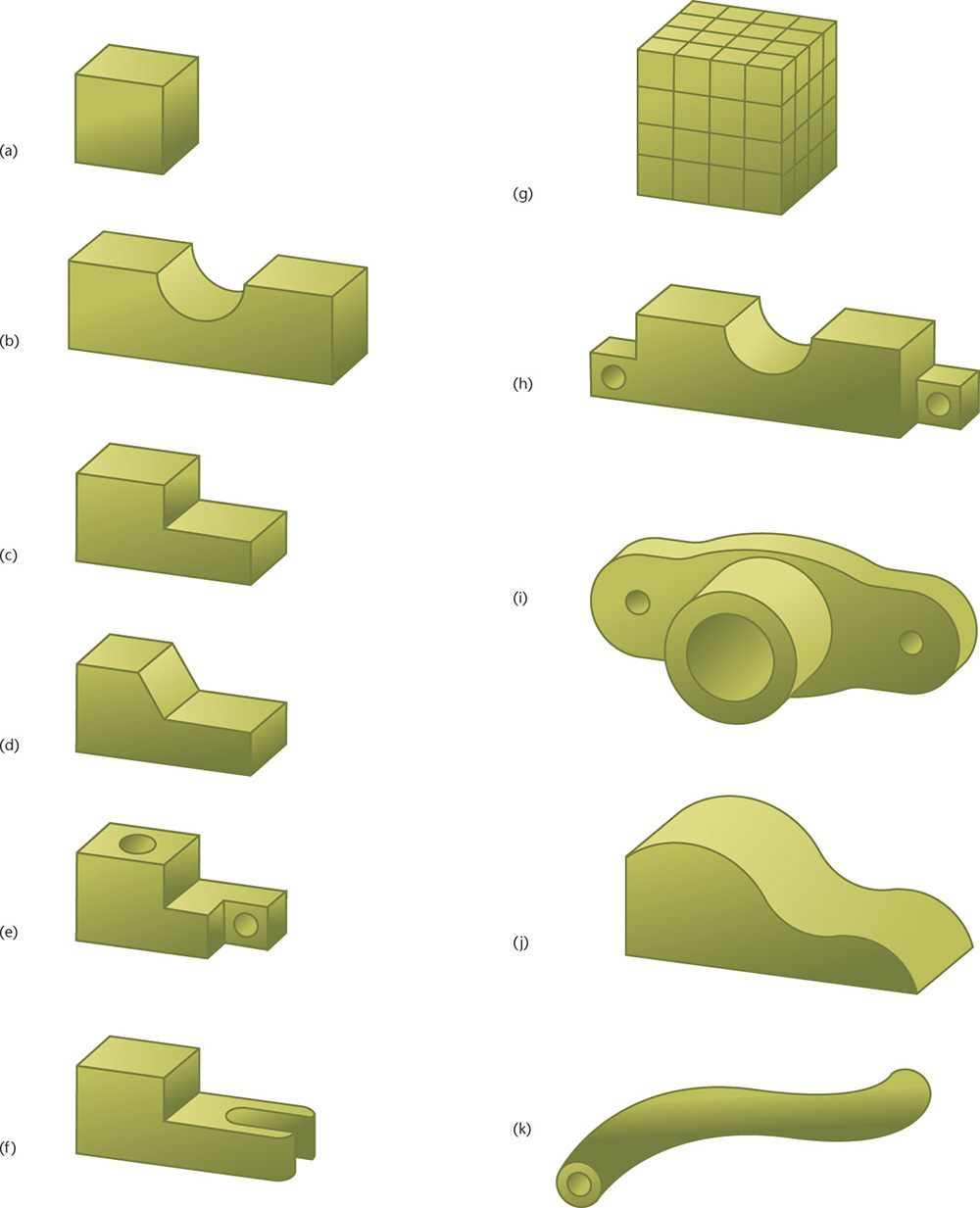

Types of Solids

Polyhedra

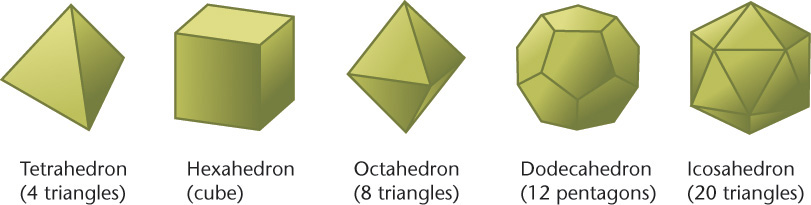

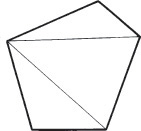

Solids that are bounded by plane surfaces are called polyhedra (Figures 3.2–3.4). These planar surfaces are also referred to as faces of the object. A polygon is a planar area that is enclosed by straight lines.

Regular Polyhedra

If the faces of a solid are equal regular polygons, it is called a regular polyhedron. There are five regular polyhedra: the tetrahedron, hexahedron, octahedron, dodecahedron, and icosahedron (Figure 3.2).

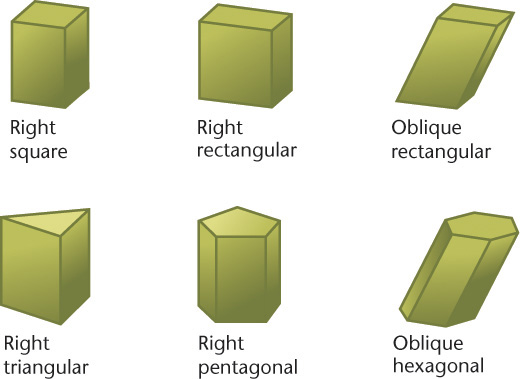

Prisms

A prism has two bases, which are parallel equal polygons, and three or more additional faces, which are parallelograms (Figure 3.3). A triangular prism has triangular bases, a rectangular prism has rectangular bases, and so on. (If a prism’s bases happen to be parallelograms, the prism is a called a parallelepiped, a word rarely heard in everyday conversation.)

A right prism has faces and lateral (side) edges that are perpendicular to the bases; an oblique prism has faces and lateral edges that are angled to the bases. If one end is cut off to form an end that is not parallel to the bases, the prism is said to be truncated (a word that simply means “shortened by having a part cut off”).

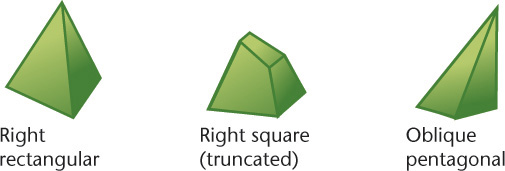

Pyramids

A pyramid has a polygon for a base and triangular lateral faces that intersect at a common point called the vertex (Figure 3.4). The line from the center of the base to the vertex is called the axis. If the axis is perpendicular to the base, the pyramid is called a right pyramid; otherwise, it is an oblique pyramid. A triangular pyramid has a triangular base, a square pyramid has a square base, and so on. If a portion near the vertex has been cut off, the pyramid is truncated, or it is referred to as a frustum.

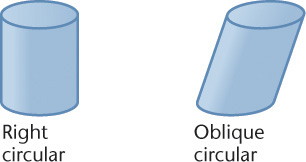

Cylinders

A cylinder has a single-curved exterior surface (Figure 3.5). You can think of a cylinder as being formed by taking a straight line and moving it in a circular path to enclose a volume. Each position of this imaginary straight line in its path around the axis is called an element of the cylinder.

Cones

A cone has a single-curved exterior surface (Figure 3.6). You can think of it as being formed by moving one end of a straight line around a circle while keeping the other end fixed at a point, the vertex of the cone. An element of the cone is any position of this imaginary straight line.

Spheres

A sphere has a double-curved exterior surface (Figure 3.7). You can think of it as being formed by revolving a circle about one of its diameters, somewhat like spinning a coin. The poles of the sphere are the points at the top and bottom of the sphere that would not move while it was spinning. The axis of the sphere is the term for the line between its poles.

Tori

A torus is shaped like a doughnut (Figure 3.8). Its boundary surface is double curved. You can think of it as being formed by revolving a circle (or other curve) around an axis that is positioned away from (outside) the curve.

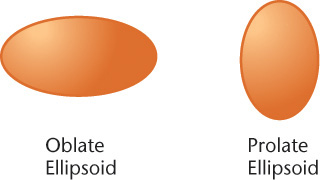

Ellipsoids

An oblate or prolate ellipsoid is shaped like an egg (Figure 3.9). You can think of it as being formed by revolving an ellipse about its minor or major axis, respectively.

Understanding Sketching Techniques

Analyzing Complex Objects

The ability to break down complex shapes into simpler geometric primitives is an essential skill for sketching and modeling objects.

Before you begin to draw the outline of an object, consider its overall shape and the relationships between its parts. Construction lines can help you preserve the overall dimensions of the object as you sketch.

Bear in mind that you should be thinking in terms of basic shapes whether you are sketching by hand or using a CAD program. Because basic curves and straight lines are the basis of many of the objects that people create, practice in creating the basic elements of a drawing will help you sketch with ease.

Essential Shapes

Look for the essential shapes of objects. If you were to make a clay model of an object, what basic shape would you start with? A ball? A box?

Try squinting your eyes and looking at familiar objects. Do you see their shape as a rectangle? A circle? What other basic shapes do you notice when you look at objects this way?

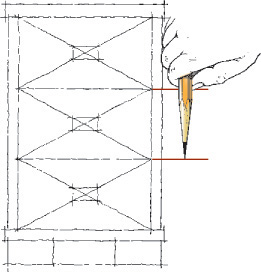

Think about breaking down more complex objects into their simpler geometric shapes as shown in Figure 3.10. You can block in these shapes using construction lines to show their relationships to one another. Then, add details, continuing to pay attention to the spatial relationships between them.

Construction Lines

Artists often begin a sketch by blocking in light guidelines to help them preserve basic shapes and proportions. In technical drawing these are called construction lines (Figure 3.12).

It is often helpful to begin a sketch by describing the object’s main shapes with construction lines, taking some care to accurately represent the relative size and placement of features.

Use the basic shapes as a guide to place key features, then use those main features as a “reference map” to place smaller details. For example, the sixth fret line is about halfway up the rectangular guitar neck.

Throughout this chapter you will use light construction lines to draw circles, arcs, and ellipses. Section 3.4 discusses the process of estimating and maintaining the proportions of an object in further detail.

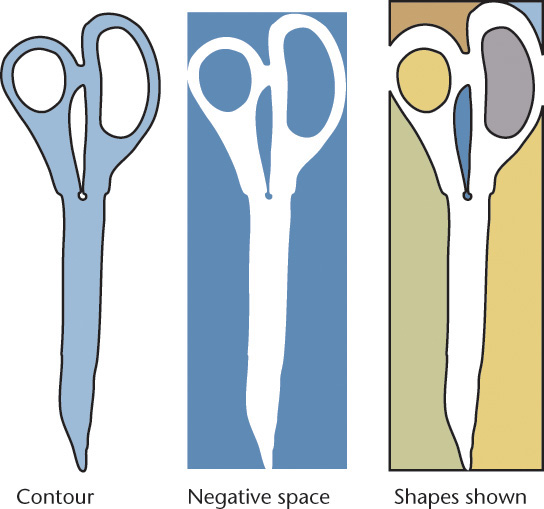

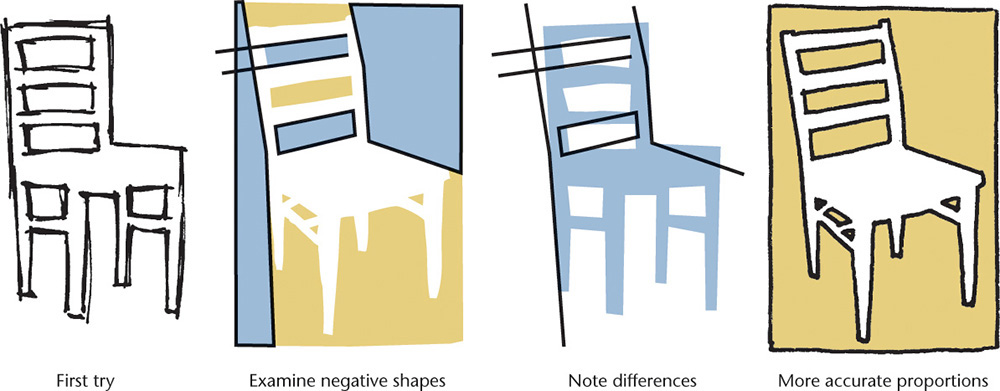

Contours and Negative Space

The contours of an object are the main outlines that separate it from the surrounding space. One way to think about the contours of objects is to look at the contrast between the positive and negative space. Positive space is the space occupied by the object. Negative space is the unoccupied space around it.

In Figure 3.13 the space occupied by the contour of a pair of scissors is shown. Note how you can identify specific shapes by looking at the negative space. The individual shapes that make up the negative space are shown in different colors to make them easier for you to see. Some people sketch more accurately when they try to draw the negative space that surrounds the object.

Tip: Practice Drawing Contours

Try sketching the negative spaces that define the shape of a chair. Look at each space as an individual shape. What is the shape of the space between the legs? What is the shape of the space between the rungs and the seat?

Make a sketch of a chair, paying careful attention to sketching the negative spaces of the chair as they really appear. The positive and negative spaces should add up to define the chair.

If you have difficulty, make corrections to your sketch by defining the positive shapes and then check to see if the negative shapes match.

An 8.5″ × 11″ sheet of Plexiglas® (available at most glass stores) is an excellent tool for developing sketching ability. Using a dry-erase marker, hold the Plexiglas up in front of an object and trace the object’s contours on the Plexiglas. If you don’t move, the outline should match the object’s outline exactly. Lower the Plexiglas and look at the orientation of the lines. Are they what you expected?

Try looking at the object and drawing the sketch with the Plexiglas lying on your desktop or knees. Then, raise it and see if your drawing matches the object.

To develop sketching ability, try drawing everyday objects like your toaster, printer, or lamp, as well as exterior and interior views of buildings and equipment.

Viewpoint

As you sketch objects, keep in mind that you want to maintain a consistent viewpoint, as a camera does. This is easier when you are sketching a picture from a book, because you can’t move around the object. When you move, you see a different view of the object depending on where you stand.

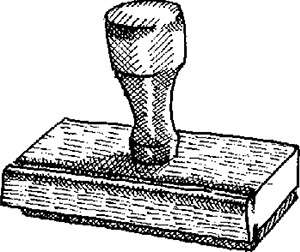

Sometimes people have difficulty sketching because they want to show parts of the object that cannot really be seen from a single viewpoint. For example, knowing that the handle of the rubber stamp in Figure 3.14 appears circular from the top, you may be tempted to show it as round, even though it may appear elliptical from your viewpoint.

When you are sketching an object pictorially, temporarily set aside your knowledge of the shapes the object is actually made of and carefully examine the shapes you see from a single, static viewpoint. In this type of sketching, instead of trying to envision the object as it is, try only to see it as it looks.

Shading

Adding shading to your sketch can give it a more realistic appearance because it represents the way the actual object would reflect light. Shading doesn’t mean “coloring in.” You may want to shade only the most prominently shadowed areas. First, identify the darkest and lightest areas on an object. If you want, you can shade various middle tones, placed exactly as they look on the object.

In some ways, shading is like doing a drawing within a drawing, because it is a matter of identifying shapes. When you are shading, instead of identifying the shapes of the object’s contours, you are identifying the shape and relative darkness of the shadows.

Hatching lines, shown in Figure 3.15, and stippling, shown in Figure 3.16, are commonly used methods to add shading because they are easier to reproduce with a photocopier than continuous-tone pencil shading. In the illustration you can see that shadowed areas are darkened simply by adding more hatching lines or stippling dots.

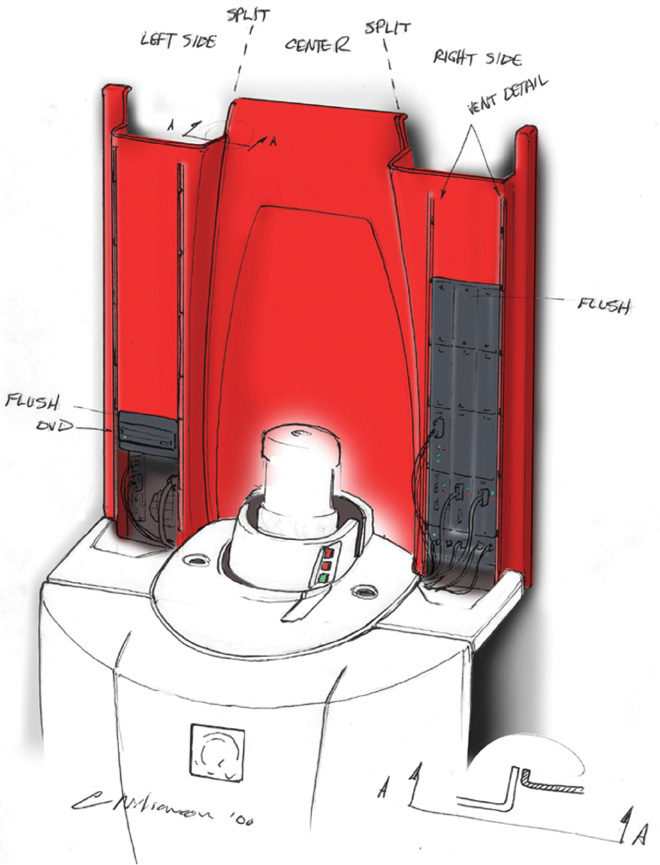

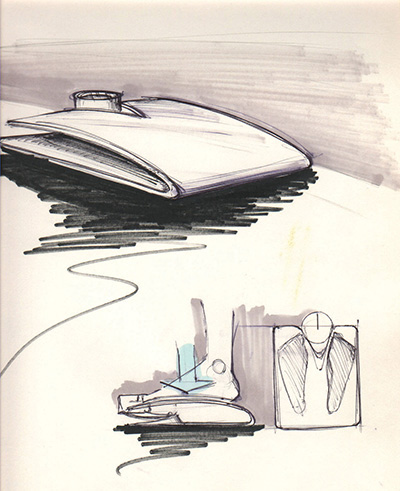

It is not uncommon for people to draw outlines by hand and add digital shaded fills to a scan of the outline. Another way to make a subject the clear focal point of a drawing is to stylize the shadows. Industrial designers often use markers to add a stylized shadow to their sketches. You can use a straight edge to protect the original sketch from the marker and quickly sketch the shadow (Figure 3.17).

Regardless of how you apply shading, darken the outline to define the shape clearly and boldly. Remember that when you are communicating by using a sketch, its subject should be clear. To make the subject—in this case, a rubber stamp—clear, make it stand out with thick bold contour lines.

Edges and Vertices

Edges

An edge of a solid is formed where two surfaces intersect. Edges are represented in drawings by visible or hidden lines (Figure 3.18).

Vertices

A vertex (plural, vertices) of a solid is formed where three or more surfaces intersect. The end of an edge is a vertex. These vertices or “points” are very useful in defining the locations of the solid object feature that you will sketch (Figure 3.18).

Points and Lines

A point is used to represent a location in space but has no width, height, or depth (Figure 3.19). A point in a drawing is represented by the intersection of two lines (Figure 3.19a), by a short crossbar on a line (Figure 3.19b), or by a small cross (Figure 3.19c). Do not represent points by simple dots on the paper. This makes the drawing look “blobby” and is not as accurate.

A line is used in drawings to represent the edge of a solid object. A straight line is the shortest distance between two points and is commonly referred to simply as a “line.” If the line is indefinite in extent, in a drawing the length is a matter of convenience, and the endpoints are not marked (Figure 3.20a). If the endpoints of the line are significant, they are marked by small drawn crossbars (Figure 3.20b). Other common terms are illustrated in Figures 3.20c to i. Either straight lines or curved lines are parallel if the shortest distance between them remains constant. The common symbol for parallel lines is | |, and for perpendicular lines it is ⊥. Two perpendicular lines may be marked with a “box” as shown in Figure 3.20g. Such symbols may be used on sketches, but not on production drawings.

Angles

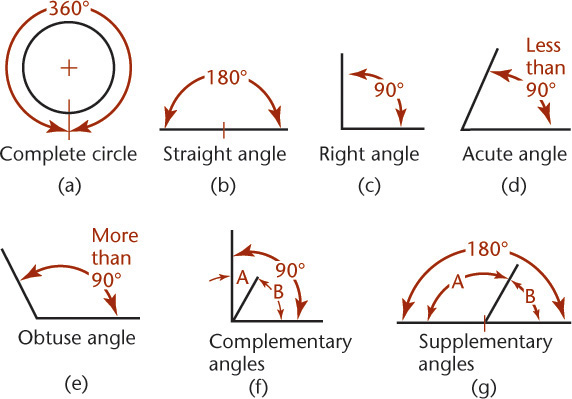

An angle is formed by two intersecting lines. A common symbol for angle is ∠.

There are 360 degrees (360°) in a full circle, as shown in Figure 3.21a. A degree is divided into 60 minutes (60′), and a minute is divided into 60 seconds (60″). The angle value 37°26′10″ is read 37 degrees, 26 minutes, and 10 seconds. When minutes alone are indicated, the number of minutes should be preceded by 0°, as in 0°20′. If the minutes value were listed alone without showing the zero value, it might be mistaken for a distance measurement. For example, 20 minutes, 10 seconds written as 20′10″ might be mistaken for 20 feet 10 inches.

The different kinds of angles are illustrated in Figure 3.21. Two angles are complementary if they total 90° (Figure 3.21f) and are supplementary if they total 180° (Figure 3.21g).

In sketching, most angles can be estimated. Use a protractor if necessary when drawing odd angles.

Drawings and Sketches

The following are important skills to keep in mind for sketches and drawings:

1. Accuracy. No drawing is useful unless it shows the information correctly.

2. Speed. Time is money in industry. Work smarter and learn to use techniques to speed up your sketching and CAD drawings while still producing neat accurate results.

3. Legibility. A drawing is a means of communicating with others, so it must be clear and legible. Give attention to details. Things that may seem picky and small as you are drawing may be significant and save money or even lives when the product is built.

4. Neatness. If a drawing is to be accurate and legible, it must also be clean.

Freehand Sketching

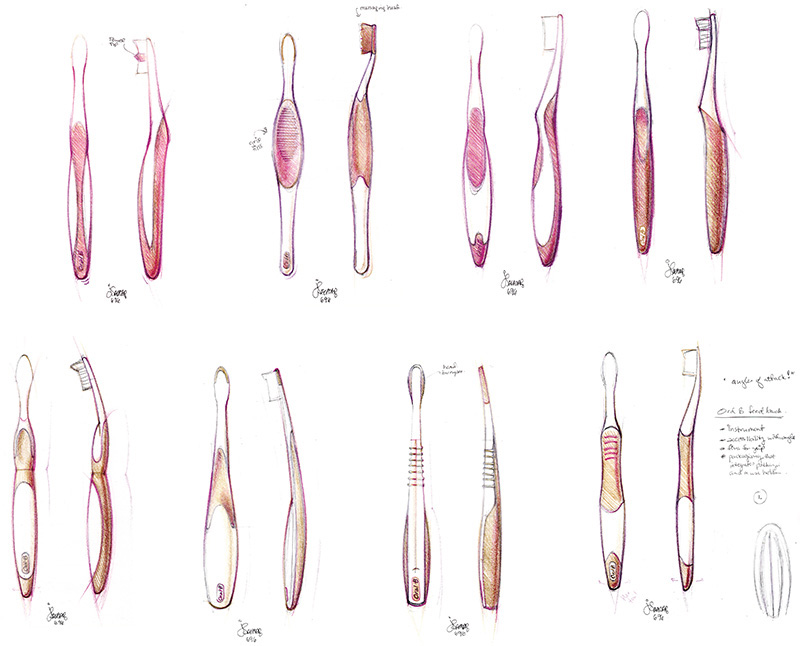

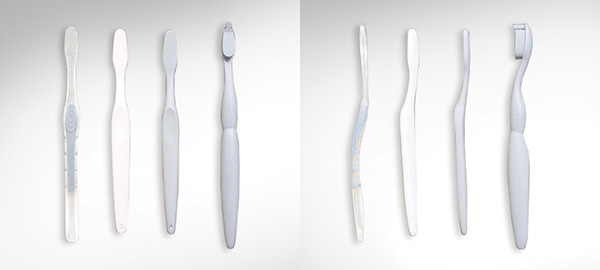

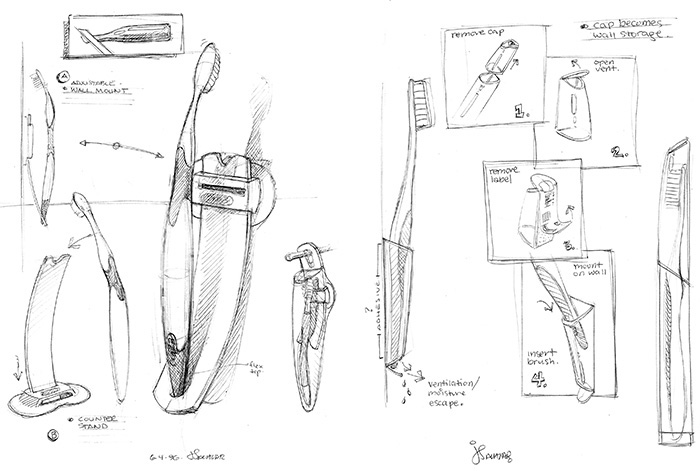

Freehand sketches are a helpful way to organize your thoughts and record ideas. They provide a quick, low-cost way to explore various solutions to design problems so that the best choices can be made. Investing too much time in creating a detailed layout before exploring your options through sketches can be costly.

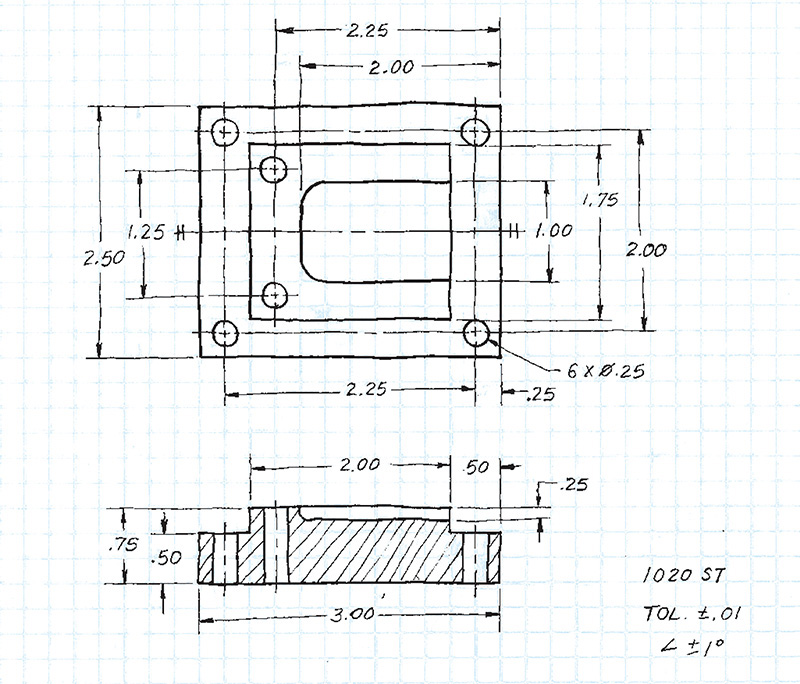

The degree of precision needed in a given sketch depends on its use. Quick sketches to supplement verbal descriptions may be rough and incomplete. Sketches can be used to convey important and precise information when they are clearly drawn and annotated.

Freehand sketching requires only pencil, paper, and eraser. Mastering the techniques in this chapter for showing quick single-view, oblique, perspective, and isometric drawings using good freehand line technique will give you a valuable tool for communicating your ideas.

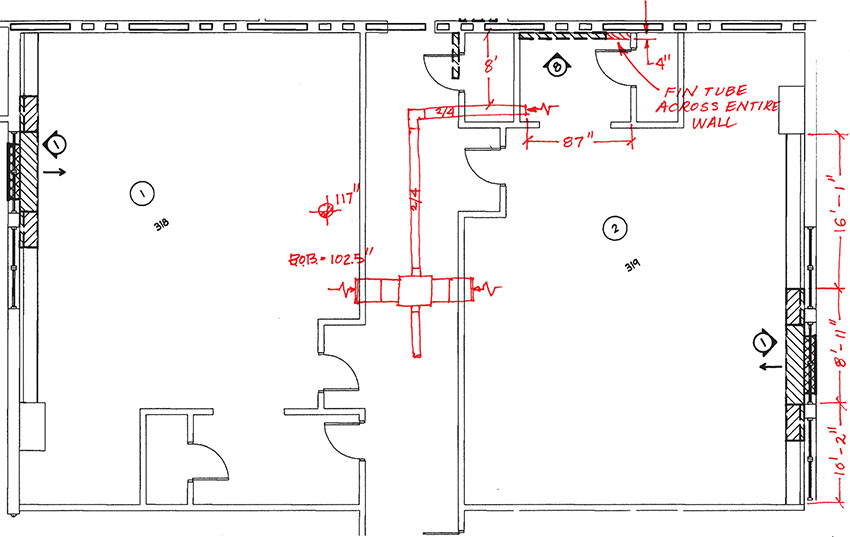

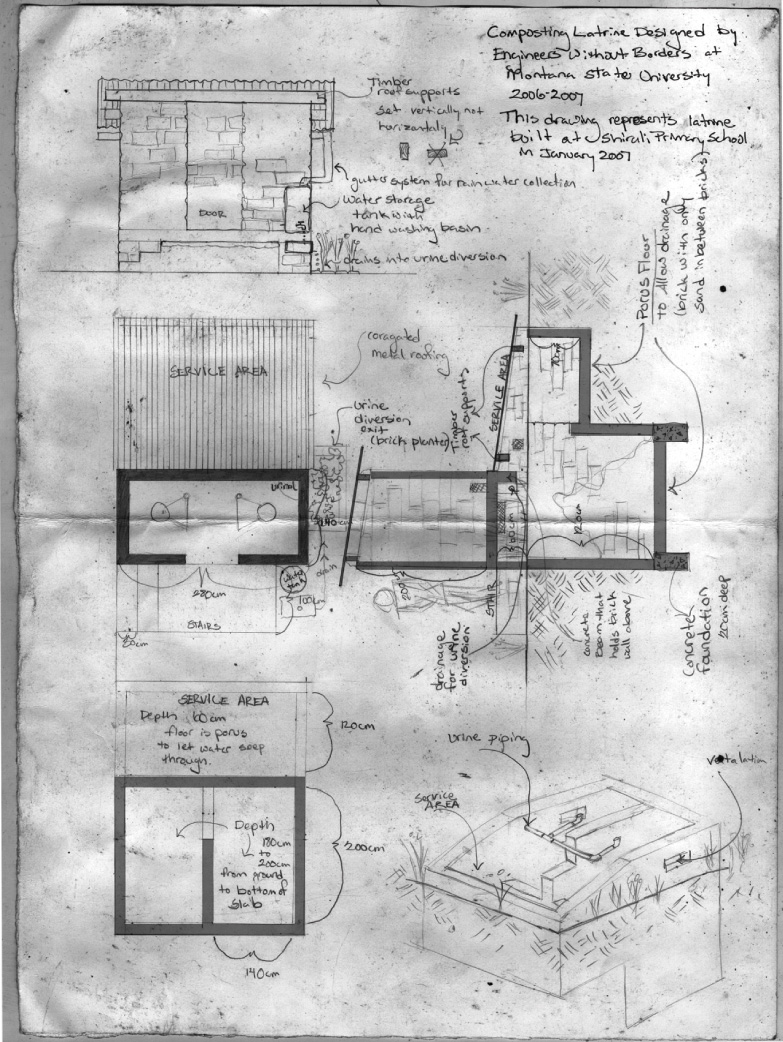

The term freehand sketch does not mean a sloppy drawing. As shown in Figure 3.22, a freehand sketch shows attention to proportion, clarity, and correct line widths. Figure 3.23 shows an as-built drawing with corrected items sketched on the printed CAD drawing.

3.22 Sketch on Graph Paper. Sketches are also used to clarify information about changes in design or to provide information on repairing existing equipment.

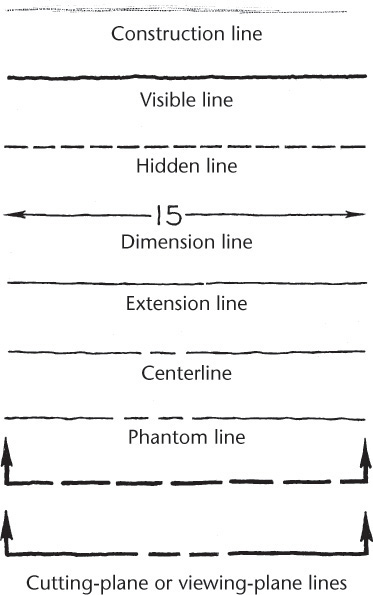

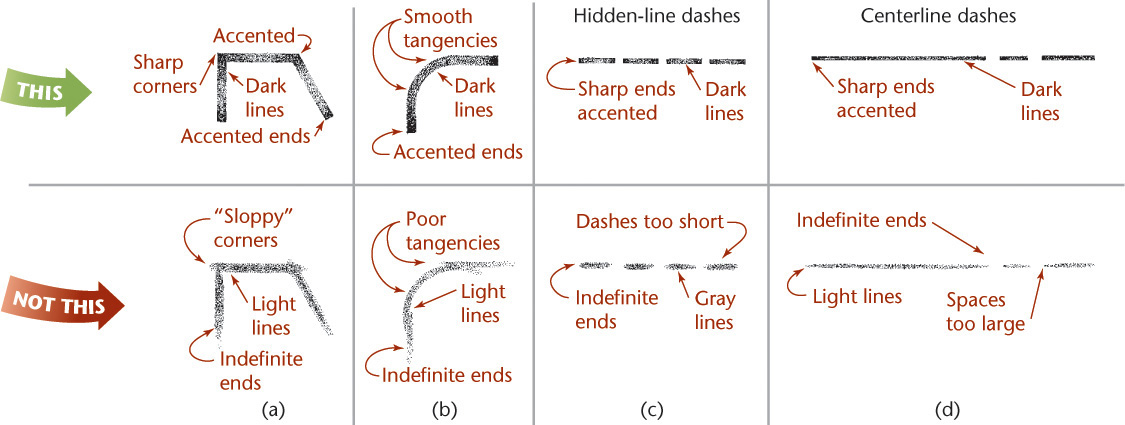

3.1 Technique of Lines

The chief difference between a drawing and a freehand sketch lies in the character or technique of the lines. A good freehand line is not expected to be as rigidly straight or exactly uniform. A good freehand line shows freedom and variety, whereas a line drawn using CAD or instruments should be exact. Still, it is important to distinguish between line patterns to make your drawing legible.

The line patterns in Figure 3.24 are examples of good freehand quality. Figure 3.25 shows examples of good and poor technique.

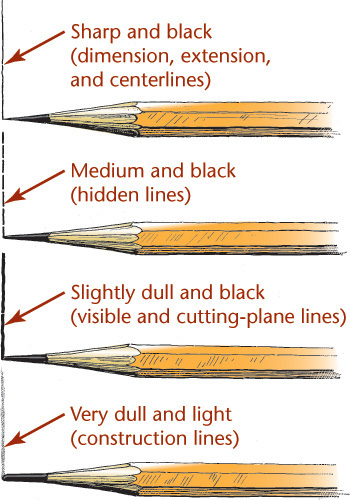

Lineweights

• Make dimension, extension, and centerlines thin, sharp, and black.

• Make hidden lines medium and black.

• Make visible and cutting-plane lines thick and black.

• Make construction lines thick and light.

Tip

Even in freehand drawings, thick lines should be twice the width of thin lines.

Thicknesses do not have to be exact, but there should be an obvious difference between thick and thin lines.

Because visible lines and cutting-plane lines are the two thick line patterns, other lines should be distinctly thinner in comparison.

To draw thick and thin lines freehand, you might like to keep two pencils handy, one that is razor sharp for thin lines and another that is dulled, to create thicker lines.

As the sharp point becomes dulled, switch it with the dull pencil, and sharpen the other, so that there is always one sharp and one dulled point ready to use.

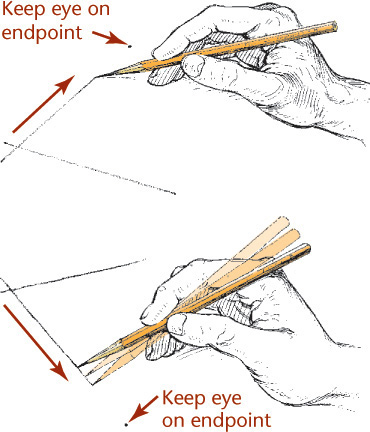

3.2 Sketching Straight Lines

Most of the lines in an average sketch are straight lines. With practice, your straight lines will naturally improve, but these basics may help you improve quickly.

• Hold your pencil naturally, about 1″ back from the point, and approximately at a right angle to the line to be drawn.

• Draw horizontal lines from left to right with a free and easy wrist and arm movement.

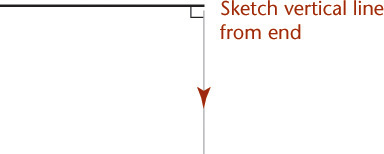

• Draw vertical lines downward with a wrist and arm movement.

• Draw curved lines using finger and wrist movements.

Blocking in a Freehand Drawing

Over the years, freehand sketchers have developed all sorts of tricks to improve speed and accuracy. Methods for finding midpoints or quickly blocking in straight vertical and horizontal lines are just a few secrets of the technical sketching craft that can come in handy, even today. When a great idea hits, or you need to sketch quickly at a meeting or on a job site, you might not have access to a CAD system, or even a ruler.

Tips: Drawing Long Freehand Lines

For long freehand lines, make light end marks and lightly sweep your pencil between them, keeping your eye on the mark toward which you are moving. When you are satisfied with the accuracy of your strokes, apply more pressure to make a dark line.

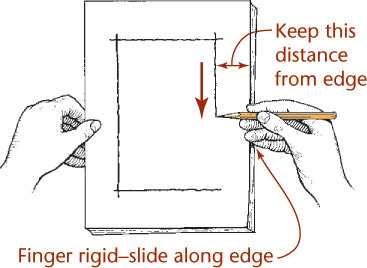

Blocking in a Border Freehand

Hold your hand and pencil rigidly and glide your fingertips along the edge of the paper to maintain a uniform border.

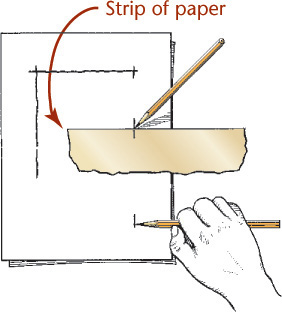

Blocking in a Border Using a Strip of Paper

Mark the distance on the edge of a card or a strip of paper and use it like a ruler to mark at intervals, then draw a final line through the points.

If your line looks like this, you may be gripping your pencil too tightly or trying too hard to imitate mechanical lines.

Slight wiggles are OK as long as the line continues on a straight path.

Occasional very slight gaps are fine and make it easier to draw straight.

Finding a Midpoint Freehand

Use your thumb on your pencil to guess half the distance. Try this distance on the other half. Continue adjusting until you locate the center, then mark it.

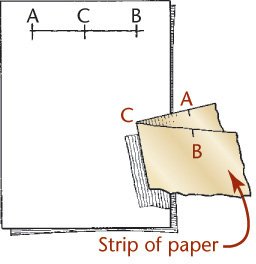

Folding a Paper to Find a Midpoint

Mark the total distance on the edge of a strip of paper, then fold the paper to locate its center at the crease. You can fold one half to find quarter points, and so on.

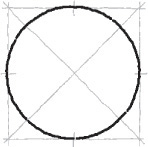

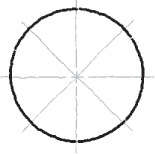

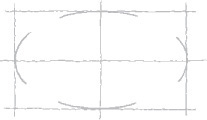

3.3 Sketching Circles, Arcs, and Ellipses

Circles

Small circles can be sketched using one or two strokes, without blocking in any construction lines. Circle templates also make it easy to sketch circles of various sizes.

For better looking freehand sketched circles of larger sizes, try the construction methods shown here. Figure 3.26 shows an object with rounded features to sketch using circles, arcs, and ellipses.

3.26 Many objects have rounded features that circles, arcs, and ellipses are used to represent. (Tim Ridley © Dorling Kindersley.)

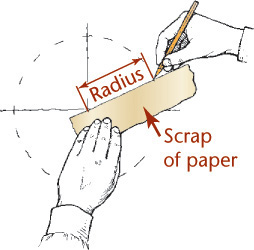

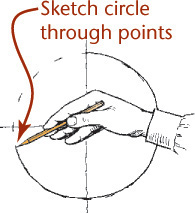

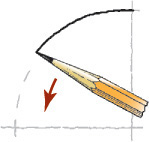

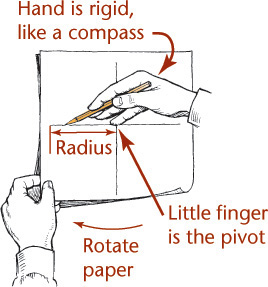

Tip: The Freehand Compass

Using your hand like a compass, you can create circles and arcs with surprising accuracy after a few minutes of practice.

1. Place the tip of your little finger or the knuckle joint of your little finger at the center.

2. “Feed” the pencil out to the radius you want as you would do with a compass.

3. Hold this position rigidly and rotate the paper with your free hand.

Sketching Arcs

Sketching arcs is similar to sketching circles. In general, it is easier to hold your pencil on the inside of the curve. Look closely at the actual geometric constructions and carefully approximate points of tangency so that the arc touches a line or other entity at the right point.

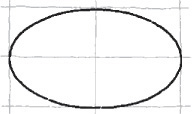

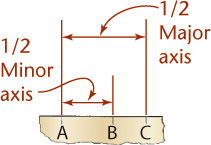

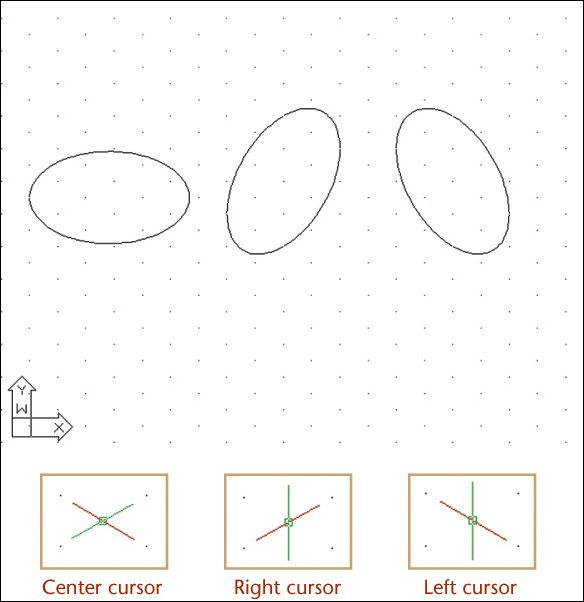

Sketching Ellipses

If a circle is tipped away from your view, it appears as an ellipse. Figure 3.27 shows a coin viewed so that it appears as an ellipse. You can learn to sketch small ellipses with a free arm movement similar to the way you sketch circles, or you can use ellipse templates to help you easily sketch ellipses. These templates are usually grouped according to the amount a circular shape would be rotated to form the ellipse. They provide a number of sizes of ellipses on each template but usually include only one or two typical rotations.

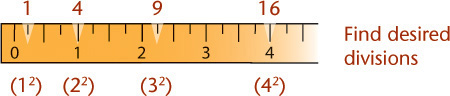

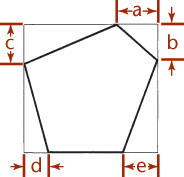

3.4 Maintaining Proportions

Sketches are not usually made to a specific scale, although it can be handy to do so at times. The size of the sketch depends on its complexity and the size of the paper available. The most important rule in freehand sketching is to keep the sketch in proportion, which means to accurately represent the size and position of each part in relation to the whole. No matter how brilliant the technique or how well drawn the details, if the proportions are off, the sketch will not look right.

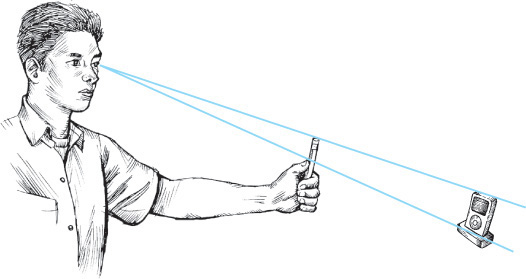

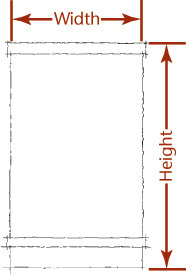

To maintain proportions, first determine the relative proportions of height to width and lightly block them in. You can mark a unit on the edge of a strip of paper or use your pencil (as in Figure 3.28) to gauge how many units wide and high the object is. Grid paper can help you maintain proportions by providing a ready-made scale (by counting squares). As you block in the medium-size areas, and later as you add small details, compare each new distance with those already established.

3.5 One-View Drawings

Frequently, a single view supplemented by notes and dimensions is enough information to describe the shape of a relatively simple object.

In Figure 3.29, one view of the shim plus a note indicating the thickness as 0.25 mm is sufficient.

Nearly all shafts, bolts, screws, and similar parts should be represented by single views in this way.

3.6 Pictorial Sketching

A pictorial sketch represents a 3D object on a 2D sheet of paper by orienting the object so you can see its width, height, and depth in a single view.

Pictorial sketches are used frequently during the ideation phase of engineering design to record ideas quickly and communicate them to others. Their similarity to how the object is viewed in the real world makes them useful for communicating engineering designs to nonengineers. Later in the design process, pictorial drawings are often used to show how parts fit together in an assembly and, in part catalogs and manuals, to make it easy to identify the objects.

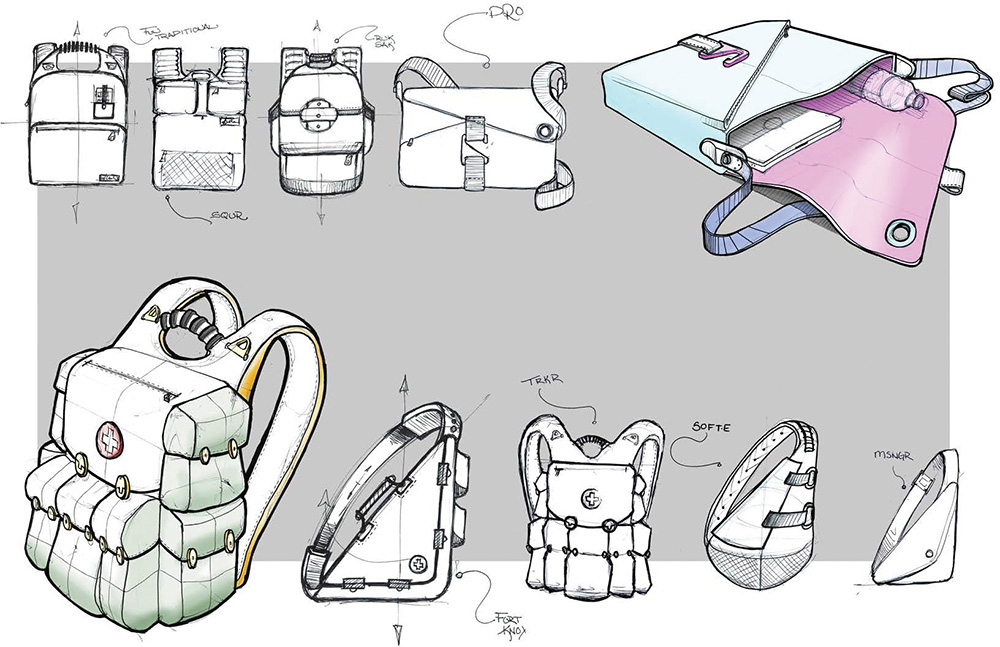

This chapter examines three common methods used to sketch pictorials: isometric sketching, which is a subtype of the general category of axonometric projection, oblique sketching, and perspective sketching. Figure 3.30 shows perspective, isometric, and oblique sketches of a stapler. Figure 3.31 shows pictorial sketches for backpack concepts.

3.31 Pictorial sketching is used frequently to convey preliminary design ideas, as in these backpack concept sketches. (Courtesy of André Cotan.)

Each of the pictorial methods differs in the way points on the object are located on the 2D viewing plane (the piece of paper).

A perspective sketch presents the most realistic looking view. It shows the object much as it would appear in a photograph—portions of the object that are farther from the viewer appear smaller, and lines recede into the distance.

An axonometric sketch is drawn so that lines do not recede into the distance but remain parallel. This makes isometric views easy to sketch but takes away somewhat from the realistic appearance.

An oblique sketch shows the front surface of the object looking straight on and is easy to create, but it presents the least realistic representation because the depth of the object appears to be out of proportion.

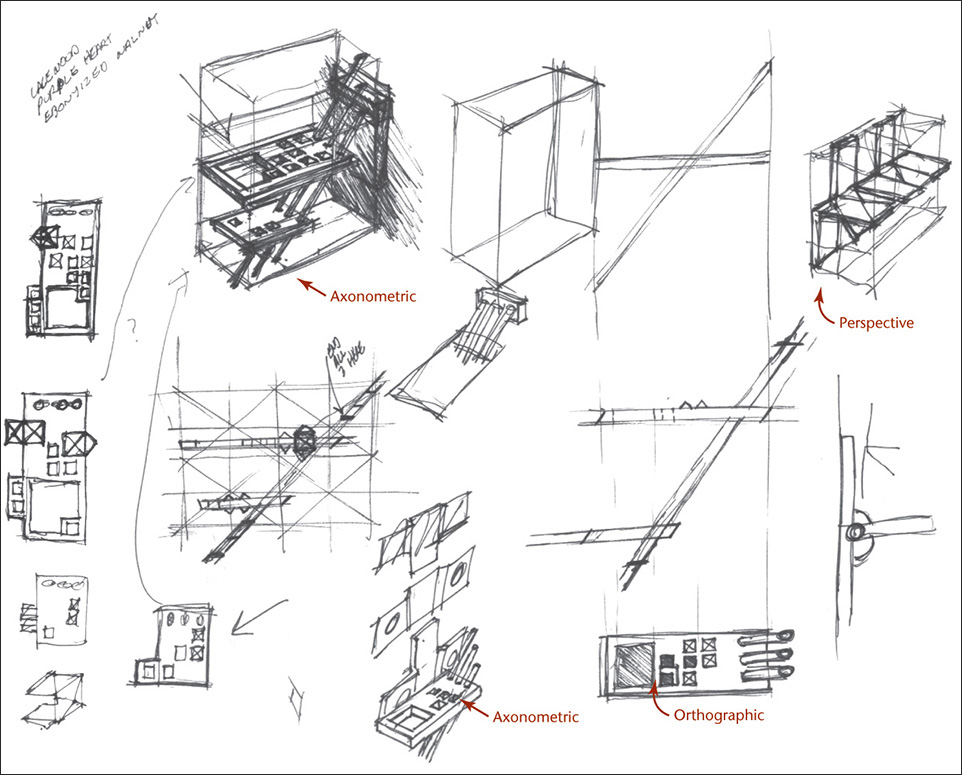

Various types of pictorial drawings are used extensively in catalogs, sales literature, and technical work. They are often used in patent drawings; in piping diagrams; in machine, structural, architectural design, and in furniture design; and for ideation sketching. The sketches for a wooden shelf in Figure 3.32 are examples of axonometric, orthographic, and perspective sketches.

3.32 Sketches for a Wooden Shelf Using Axonometric, Orthographic, and Perspective Drawing Techniques. The axonometric projections in this sketch are drawn in isometric. (Courtesy of Douglas Wintin.)

In axonometric and oblique drawings, distant features are not shown proportionately smaller, the way they appear in a photograph or to our vision. Edges that are parallel on the object always appear parallel in an axonometric view. The most common axonometric projection is isometric, which means “equal measure.” When a cube is drawn in isometric, the axes are equally spaced (120° apart). Though not as realistic as perspective drawings, isometric drawings are much easier to draw. CAD software often displays the results of 3D models on the screen as isometric projections. Some CAD software allows you to choose between isometric, axonometric views (see Figure 3.35 for examples), or perspective representation of your 3D models on the 2D computer screen. In sketching, dimetric and trimetric sometimes produce a better view than isometric but take longer to draw and are therefore used less frequently.

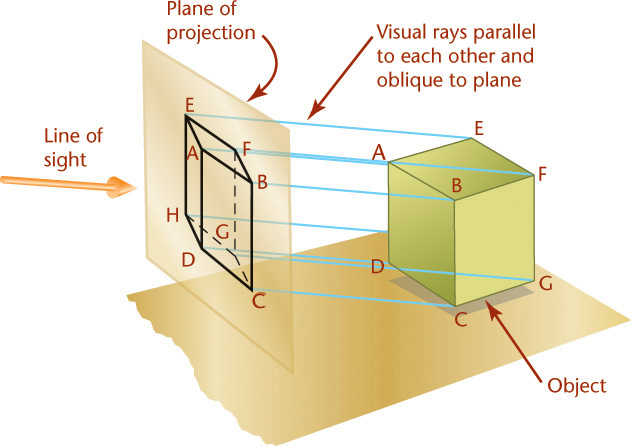

3.7 Projection Methods

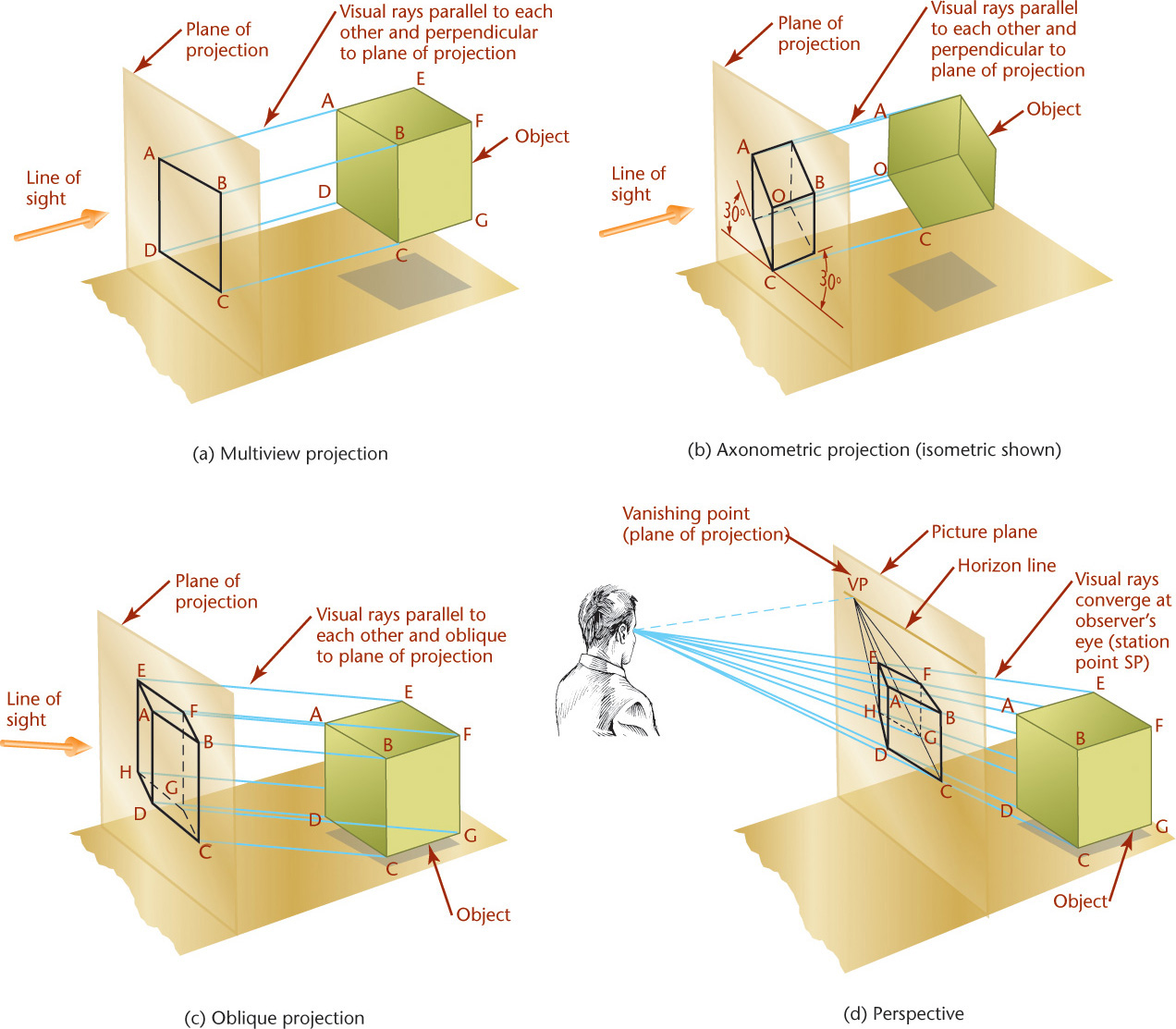

The four principal types of projection are shown in Figure 3.33. All except the regular multiview projection (Figure 3.33a) are pictorial types, because they show several sides of the object in a single view. In both multiview projection and axonometric projection, the visual rays are parallel to each other and perpendicular to the plane of projection. Both are types of orthographic projection (Figures 3.33a and 3.33b).

In oblique projection (Figure 3.33c), the visual rays are parallel to each other but at an angle other than 90° to the plane of projection.

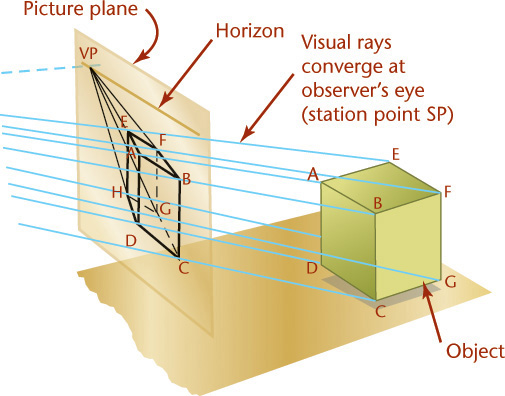

In perspective (Figure 3.33d), the visual rays extend from the observer’s eye, or station point (SP), to all points of the object to form a “cone of rays,” so that the portions of the object that are farther away from the observer appear smaller than the closer portions of the object.

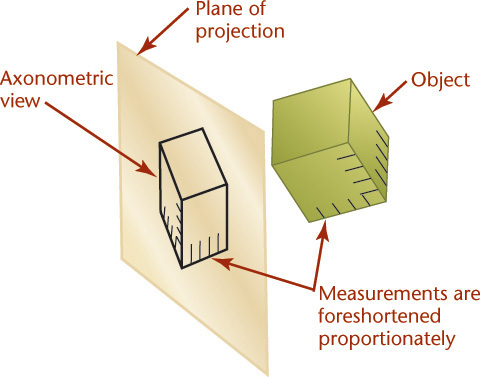

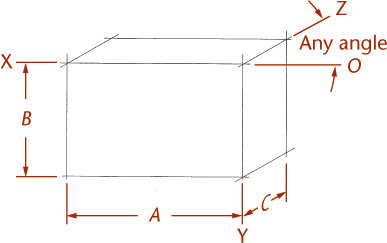

3.8 Axonometric Projection

The feature that distinguishes axonometric projection from multiview projection is the inclined position of the object with respect to the planes of projection. When a surface or edge of the object is not parallel to the plane of projection, it appears foreshortened. When an angle is not parallel to the plane of projection, it appears either smaller or larger than the true angle.

To create an axonometric view, the object is tipped to the planes of projection so that principal faces, such as the top, side, and front, show in a single view. This produces a pictorial drawing that is easy to visualize, but because the principal edges and surfaces of the object are inclined to the plane of projection, the lengths of the lines are foreshortened. The angles between surfaces and edges appear either larger or smaller than the true angle. There are an infinite variety of ways that the object may be oriented with respect to the plane of projection.

The degree of foreshortening of any line depends on its angle to the plane of projection. The greater the angle, the greater the foreshortening. Once the degree of foreshortening is determined for each of the three edges of the cube that meet at one corner, scales can be easily constructed for measuring along these edges or any other edges parallel to them (Figure 3.34).

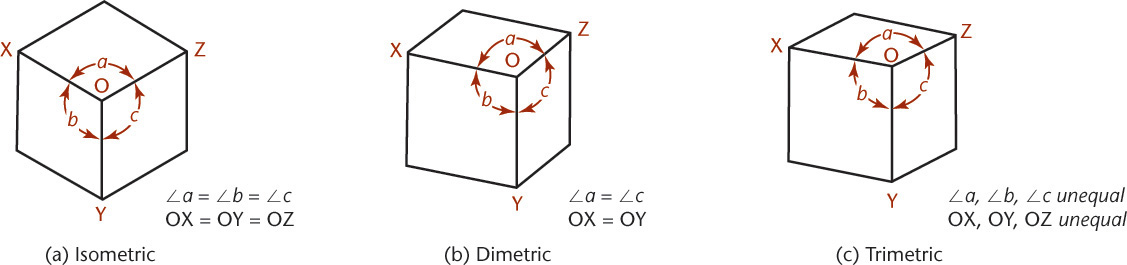

Use the three edges of the cube that meet at the corner nearest your view as the axonometric axes. Figure 3.35 shows three axonometric projections.

Isometric projection (Figure 3.35a) has equal foreshortening along each of the three axis directions.

Dimetric projection (Figure 3.35b) has equal foreshortening along two axis directions and a different amount of foreshortening along the third axis. This is because it is not tipped an equal amount to all the principal planes of projection.

Trimetric projection (Figure 3.35c) has different foreshortening along all three axis directions. This view is produced by an object that is unequally tipped to all the planes of projection.

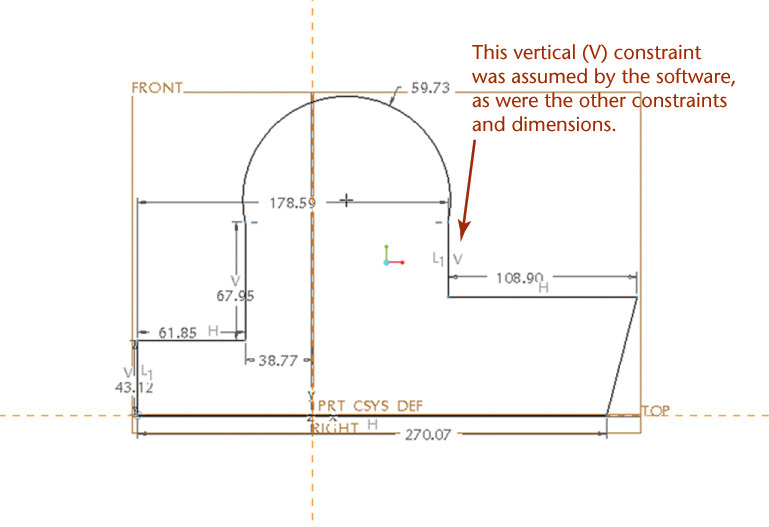

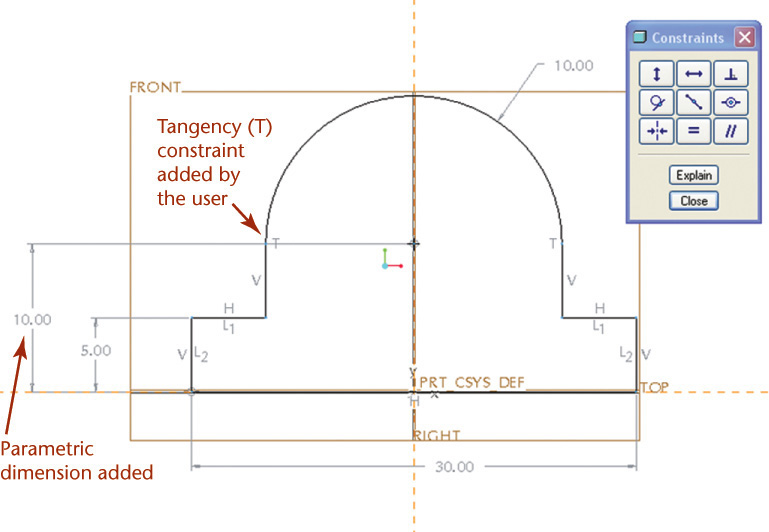

Axonometric Projections and 3D Models

When you create a 3D CAD model, the object is stored so that vertices, surfaces, and solids are all defined relative to a 3D coordinate system. You can rotate your view of the object to produce a view from any direction. However, your computer screen is a flat surface, like a sheet of paper. The CAD software uses similar projection to produce the view transformations, creating the 2D view of the object on your computer screen. Most 3D CAD software provides a variety of preset isometric viewing directions to make it easy for you to manipulate the view. Some CAD software also allows for easy perspective viewing on screen.

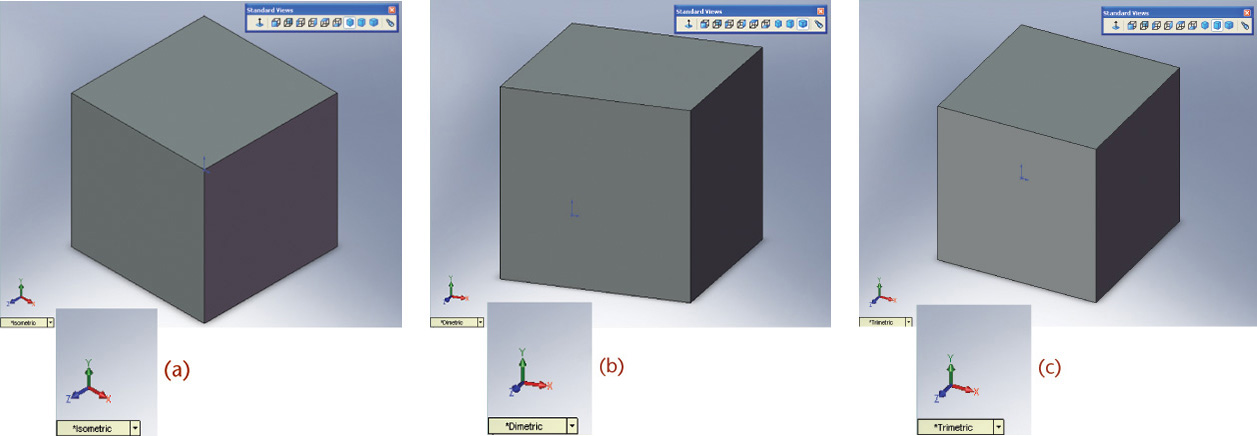

After rotating the object you may want to return to a preset typical axonometric view like one of the examples shown in Figure 3.36.

3.36 (a) Isometric View of a 1″ Cube Shown in SolidWorks; (b) Dimetric View; (c) Trimetric View (Images courtesy of ©2016 Dassault Systèmes SolidWorks Corporation.)

3.9 Isometric Projection

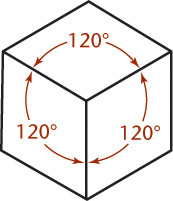

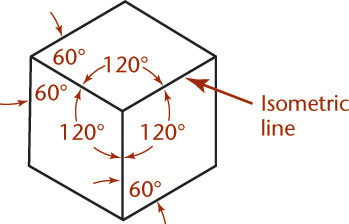

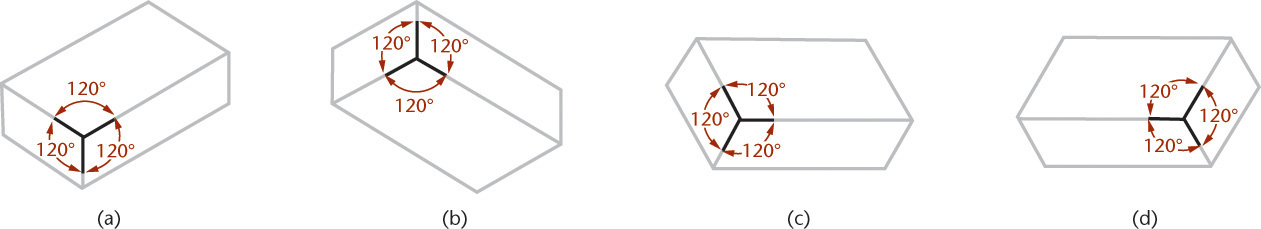

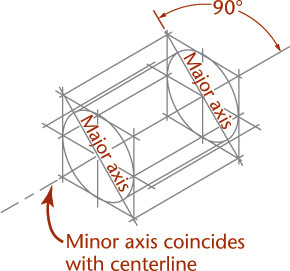

In an isometric projection, all angles between the axonometric axes are equal. To produce an isometric projection, you orient the object so that its principal edges (or axes) make equal angles with the plane of projection and are therefore foreshortened equally. Oriented this way, the edges of a cube are projected so that they all measure the same and make equal angles (of 120°) with each other, as shown in Figure 3.37.

Isometric Axes

The projections of the edges of a cube make angles of 120° with each other. You can use these as the isometric axes from which to make measurements. Any line parallel to one of these is called an isometric line. The angles in the isometric projection of the cube are either 120° or 60°, and all are projections of 90° angles. In an isometric projection of a cube, the faces of the cube, and any planes parallel to them, are called isometric planes. See Figure 3.38.

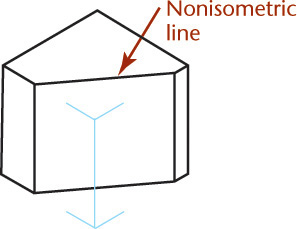

Nonisometric Lines

Lines of an isometric drawing that are not parallel to the isometric axes are called nonisometric lines (Figure 3.39). Only lines of an object that are drawn parallel to the isometric axes are equally foreshortened. Nonisometric lines are drawn at other angles and are not equally foreshortened. Therefore the lengths of features along nonisometric lines cannot be measured directly with a scale.

Isometric Scales

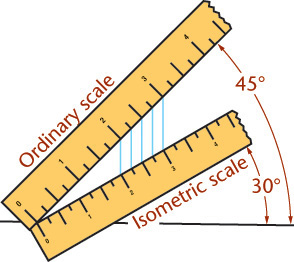

An isometric scale can be used to draw correct isometric projections. All distances in this scale are 2/3 × true size, or approximately 80% of true size. Figure 3.40a shows an isometric scale. More commonly, an isometric sketch or drawing is created using a standard scale, as in Figure 3.40b, disregarding the foreshortening that the tipped surfaces would produce in a true projection. Figure 3.40c shows an isometric view of a 10″ cube modeled in 3D. When measured parallel to the view, the length appears to be 8.1650 due to the foreshortening (near 80% of the actual size).

Tip: Making an Isometric Scale

You can make an isometric scale from a strip of paper or cardboard by placing an ordinary scale at 45° to a horizontal line and the paper (isometric) scale at 30° to the horizontal line. To mark the increments on the isometric scale, draw straight lines (perpendicular to the horizontal line) from the division lines on the ordinary scale.

Alternatively, you can approximate an isometric scale. Scaled measurements of 9″ = 1′–0, or three-quarter-size scale (or metric equivalent) can be used as an approximation.

3.10 Isometric Drawings

When you make a drawing using foreshortened measurements, or when the object is actually projected on a plane of projection, it is called an isometric projection (Figure 3.40a). When you make a drawing using the full-length measurements of the actual object, it is an isometric sketch or isometric drawing (Figure 3.40b) to indicate that it lacks foreshortening.

The isometric drawing is about 25% larger than the isometric projection, but the pictorial value is obviously the same in both. Because isometric sketches are quicker (because you can use the actual measurements), they are much more commonly drawn.

Tip

Some CAD software will notify you about the lack of foreshortening in isometric drawings (or allow you to select for it) when you print or save them.

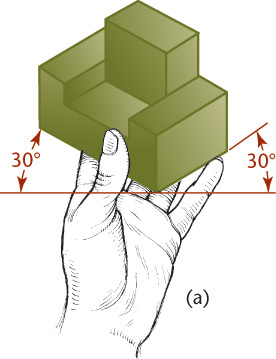

Positions of the Isometric Axes

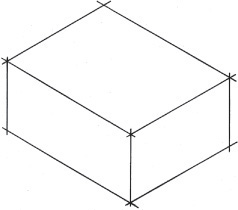

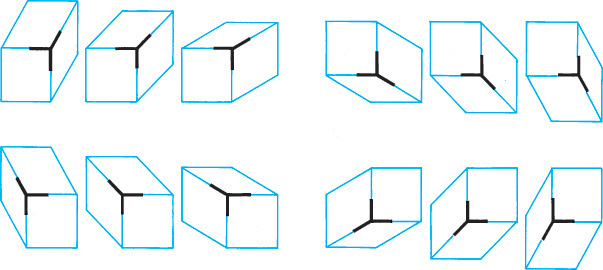

The first step in making an isometric drawing is to decide along which axis direction to show the height, width, and depth, respectively. Figure 3.41 shows four different orientations that you might start with to create an isometric drawing of the block shown. Each is an isometric drawing of the same block, but with a different corner facing your view. These are only a few of many possible orientations.

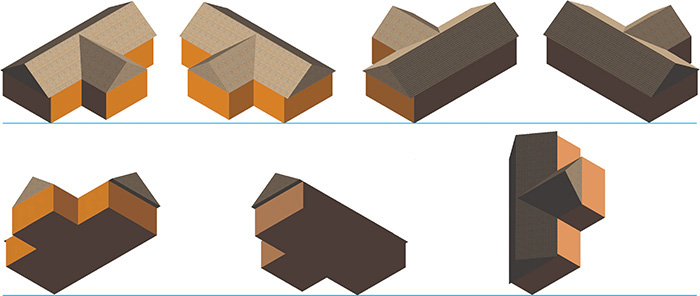

3.42 Isometric Options. These views of a simple model of a house are all isometric, but some show the features best.

You may orient the axes in any desired position, but the angle between them must remain 120°. In selecting an orientation for the axes, choose the position from which the object is usually viewed, or determine the position that best describes the shape of the object, or better yet, both.

If the object is a long part, it will look best with the long axis oriented horizontally.

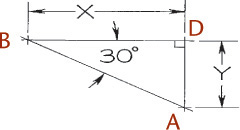

3.11 Making an Isometric Drawing

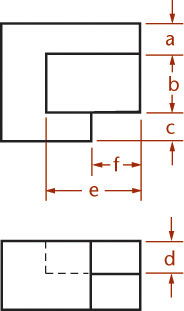

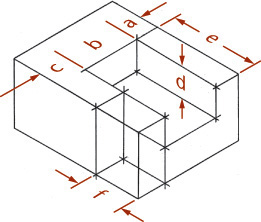

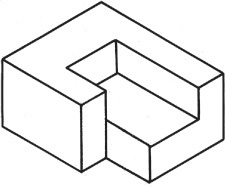

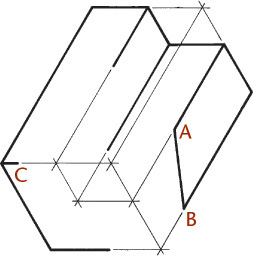

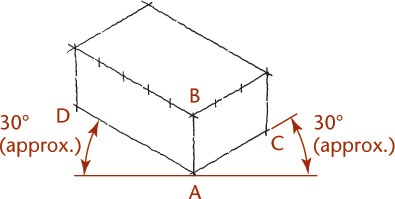

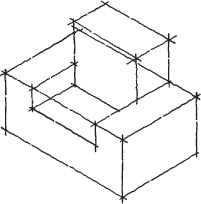

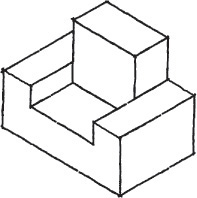

Rectangular objects are easy to draw using box construction, which consists of imagining the object enclosed in a rectangular box whose sides coincide with the main faces of the object. For example, imagine the object shown in the two views in the Step by Step feature at right enclosed in a construction box, then locate the features along the edges of the box as shown.

The Step by Step feature on the next page shows how to construct an isometric drawing of an object composed of all “normal” surfaces. Normal is used technically to mean “at right angles.” A normal surface is any surface that is parallel to the sides of the box. Notice that all measurements are made parallel to the main edges of the enclosing box—that is, parallel to the isometric axes. No measurement along a nonisometric line can be measured directly with the scale, as these lines are not foreshortened equally to the normal lines. Start at any one of the corners of the bounding box and draw along the isometric axis directions.

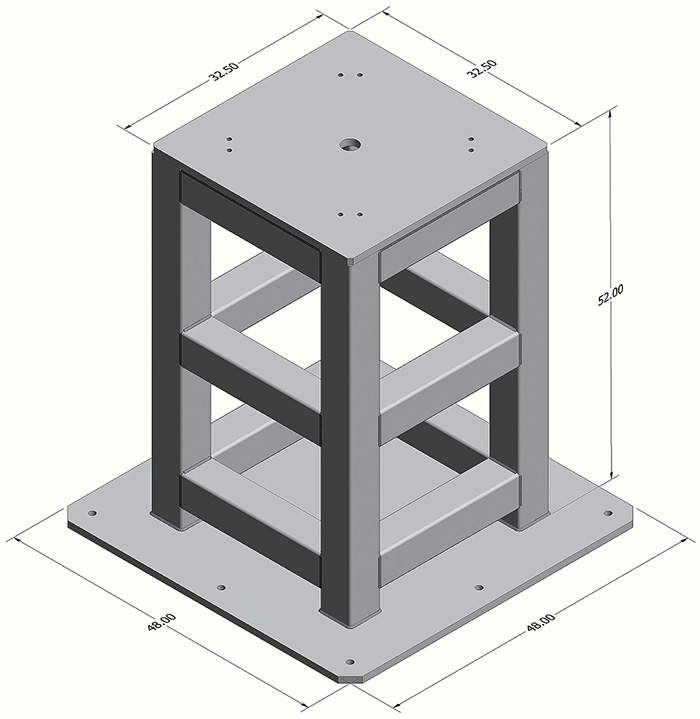

3.43 Isometric drawings are not typically dimensioned. When they are, the dimensions should appear in the same plane as the isometric axes and read from the bottom of the sheet or aligned in the isometric planes. (Courtesy of Brandon Wold.)

3.12 Offset Location Measurements

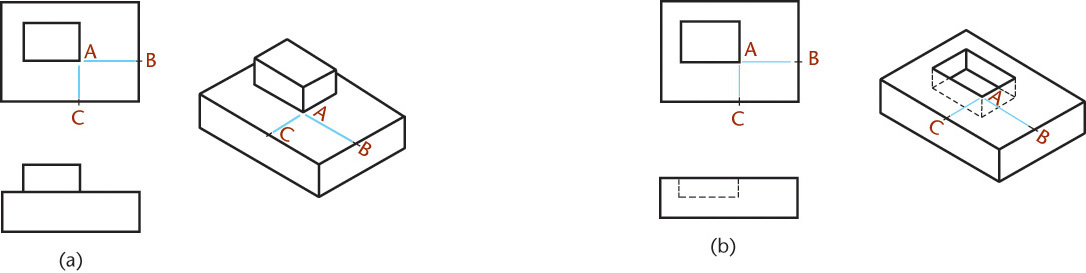

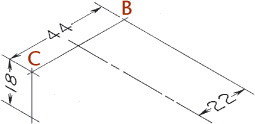

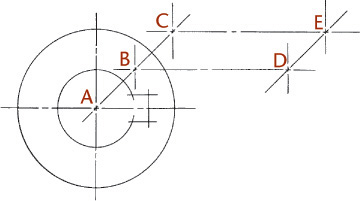

Use the method shown in Figures 3.44a and b to locate points with respect to each other. First, draw the main enclosing block, then draw the offset lines (CA and BA) full size in the isometric drawing to locate corner A of the small block or rectangular recess. These measurements are called offset measurements. Because they are parallel to edges of the main block in the multiview drawings, they will be parallel to the same edges in the isometric drawings (using the rule of parallelism).

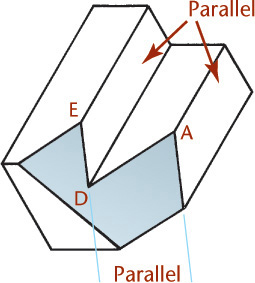

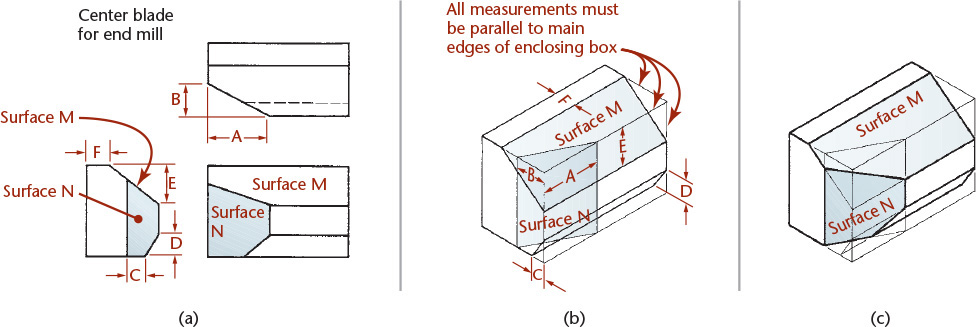

Isometric Drawings of Inclined Surfaces

Figure 3.45 shows how to construct an isometric drawing of an object that has some inclined surfaces and oblique edges. Notice that inclined surfaces are located by offset or coordinate measurements along the isometric lines. For example, dimensions E and F are measured to locate the inclined surface M, and dimensions A and B are used to locate surface N.

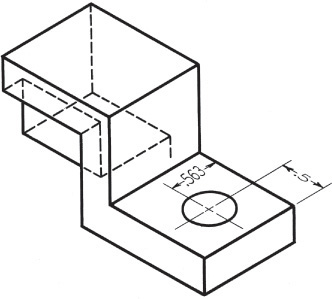

3.13 Hidden Lines and Centerlines

Hidden lines in a drawing represent the edges where surfaces meet but are not directly visible. Hidden lines are omitted from pictorial drawings unless they are needed to make the drawing clear. Figure 3.46 shows a case in which hidden lines are needed because a projecting part cannot be clearly shown without them. Sometimes it is better to include an isometric view from another direction than to try to show hidden features with hidden lines. You will learn more about hidden lines in Chapter 6.

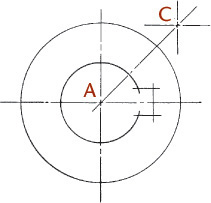

Draw centerlines locating the center of a hole only if they are needed to indicate symmetry or for dimensioning. In general, use centerlines sparingly in isometric drawings. If in doubt, leave them out, as too many centerlines will look confusing.

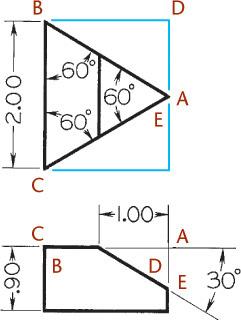

3.14 Angles in Isometric

Angles project true size only when the plane containing the angle is parallel to the plane of projection. An angle may project to appear larger or smaller than the true angle depending on its position.

Because the various surfaces of the object are usually inclined to the front plane of projection, they generally will not be projected true size in an isometric drawing.

Tip: Checking Isometric Angles

To convince yourself that none of the angles will be 60°, measure each angle in the isometric in the figure above with a protractor or scrap of paper and note the angle compared with the true 60°. None of the angles shown are the same in the isometric drawing. Two are smaller and one is larger than 60°.

Estimating 30° Angles

If you are sketching on graph paper and estimating angles, an angle of 30° is roughly a rise of 1 to a run of 2.

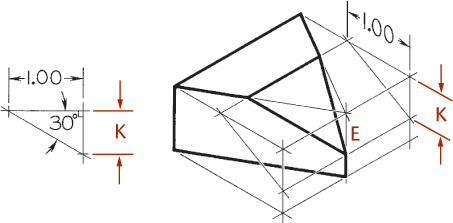

3.15 Irregular Objects

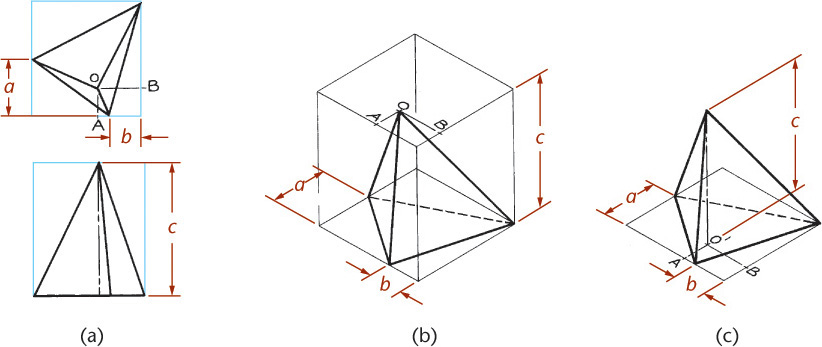

You can use the construction box method to draw objects that are not rectangular (Figure 3.47). Locate the points of the triangular base by offsetting a and b along the edges of the bottom of the construction box. Locate the vertex by offsetting lines OA and OB using the top of the construction box.

Tip

It is not always necessary to draw the complete construction box as shown in Figure 3.47b. If only the bottom of the box is drawn, the triangular base can be constructed as before. The orthographic projection of the vertex O’ on the base can be drawn using offsets O’A and O’B, as shown, and then the vertical line O’O can be drawn, using measurement C.

Tennis Ball (Factory Reject) (Excerpted from Droodles – The Classic Collection by Roger Price ©2000 by Tallfellow Press. Used by permission. All rights reserved.)

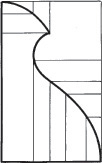

3.16 Curves in Isometric

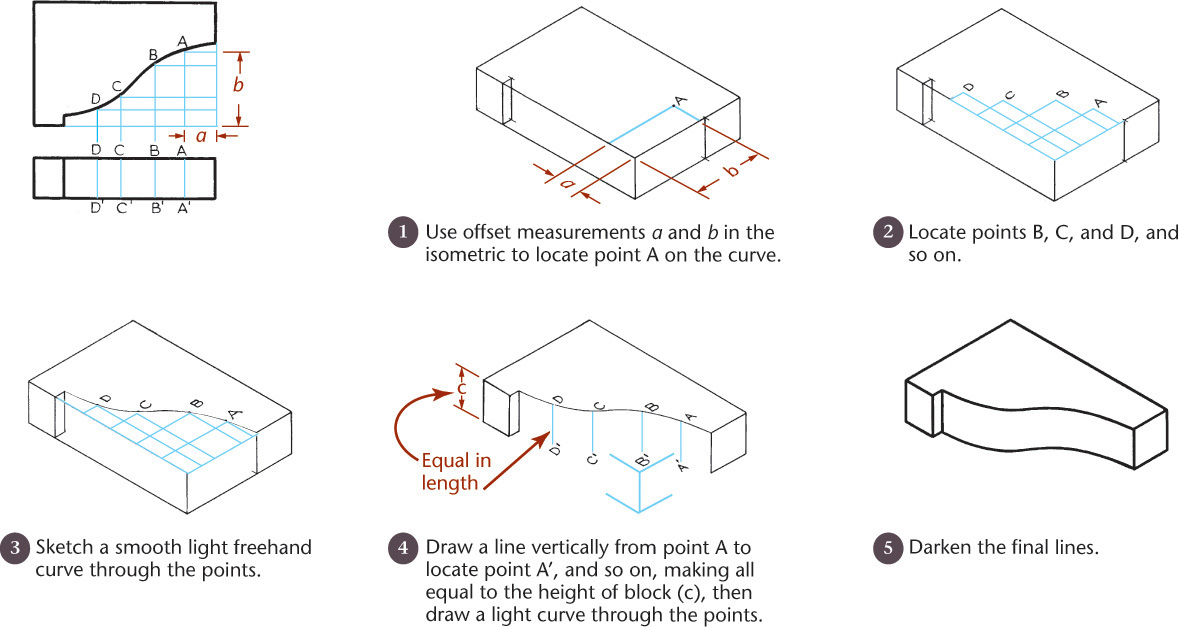

You can draw curves in isometric using a series of offset measurements similar to those discussed in Section 3.12. Select any desired number of points at random along the curve in the given top view, such as points A, B, and C in Figure 3.48. Choose enough points to accurately locate the path of the curve (the more points, the greater the accuracy). Draw offset grid lines from each point parallel to the isometric axes and use them to locate each point in the isometric drawing as in the example shown in Figure 3.48.

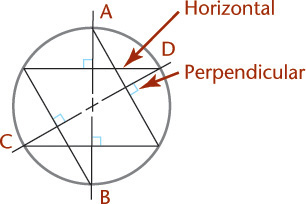

3.17 True Ellipses in Isometric

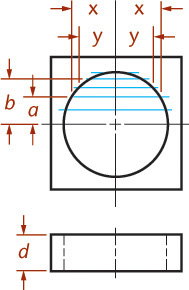

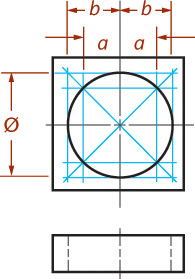

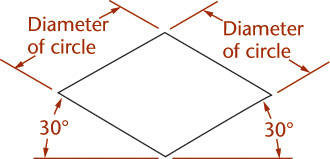

If a circle lies in a plane that is not parallel to the plane of projection, the circle projects as an ellipse. The ellipse can be constructed using offset measurements.

3.18 Orienting Ellipses in Isometric Drawings

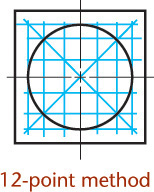

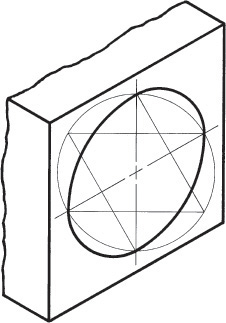

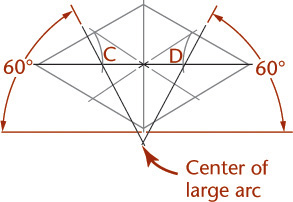

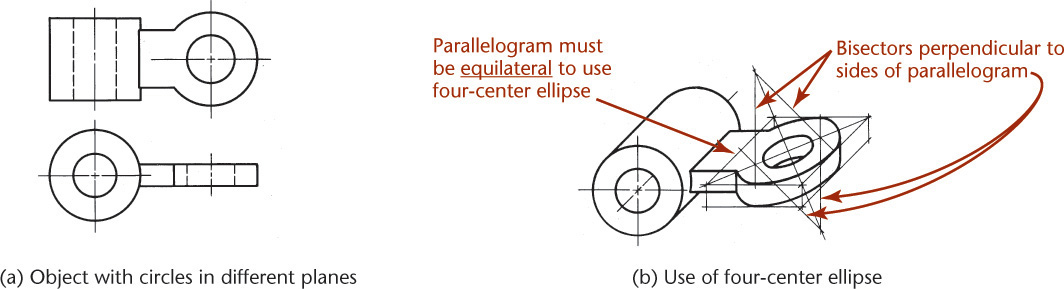

Figure 3.49 shows four-center ellipses constructed on the three visible faces of a cube. Note that all the diagonals are horizontal or at 60° with horizontal. Realizing this makes it easier to draw the shapes.

Approximate ellipses such as these, constructed from four arcs, are accurate enough for most isometric drawings. The four-center method can be used only for ellipses in isometric planes. Earlier versions of CAD software, such as AutoCAD Release 10, used this method to create the approximate elliptical shapes available in the software. Current releases use an accurate ellipse.

More Accurate Ellipses

The four-center ellipse deviates considerably from a true ellipse. As shown in Figure 3.50a, a four-center ellipse is somewhat shorter and “fatter” than a true ellipse. When the four-center ellipse is not accurate enough, you can use a closer approximation called the Orth four-center ellipse to produce a more accurate drawing.

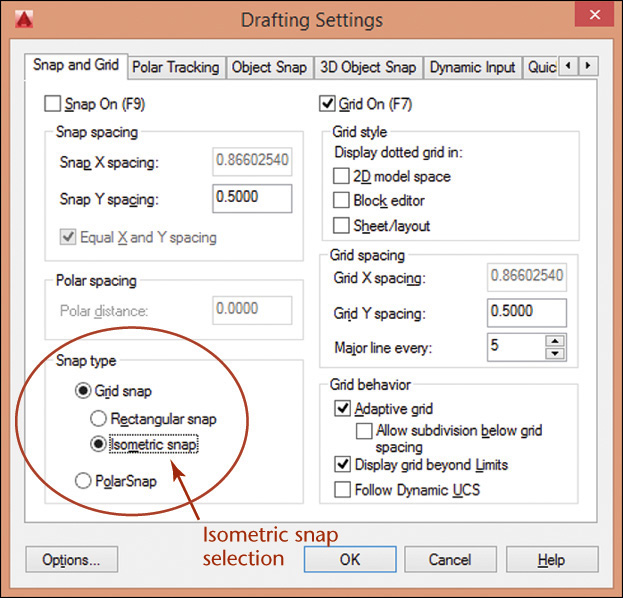

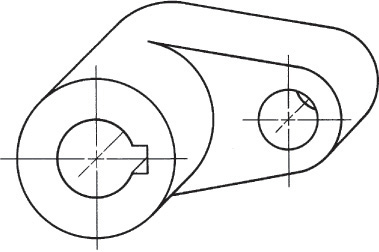

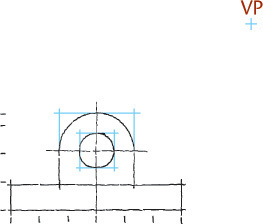

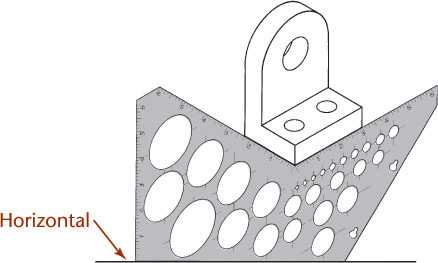

Special templates like this isometric template with angled lines and ellipses oriented in various isometric planes make it easy to draw isometric sketches. The ellipses are provided with markings to coincide with the isometric centerlines of the holes—a convenient feature in isometric drawing.

You can also draw ellipses using an ellipse template. Select the size and alignment of the major and minor axes of the ellipse to match the orientation of the shape in your drawing.

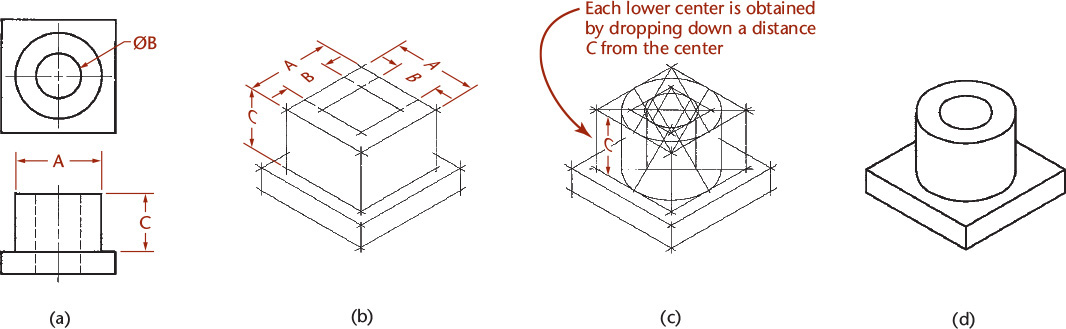

3.19 Drawing Isometric Cylinders

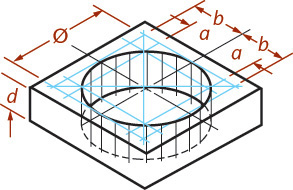

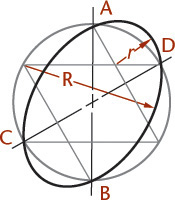

A typical drawing with cylindrical shapes is shown in Figure 3.51. Note that the centers of the larger ellipse cannot be used for the smaller ellipse, though the ellipses represent concentric circles. Each ellipse has its own parallelogram and its own centers. Notice that the centers of the lower large ellipse are drawn by projecting the centers of the upper large ellipse down a distance equal to the height of the cylinder.

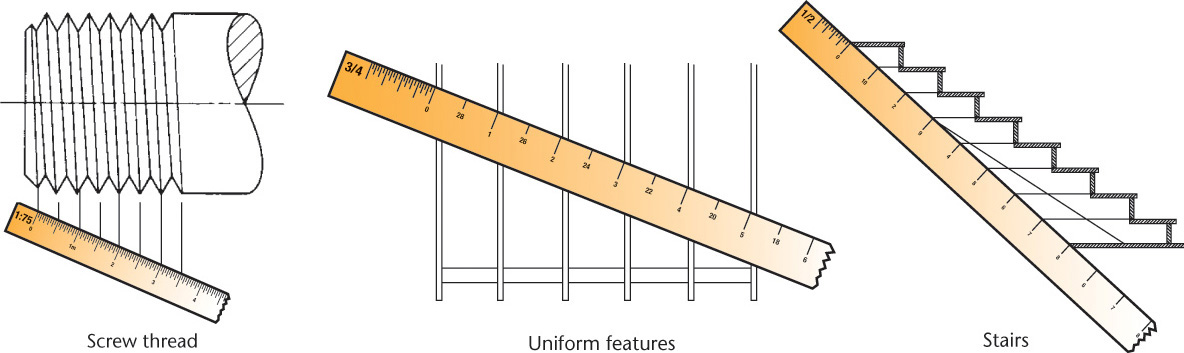

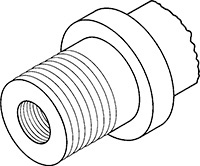

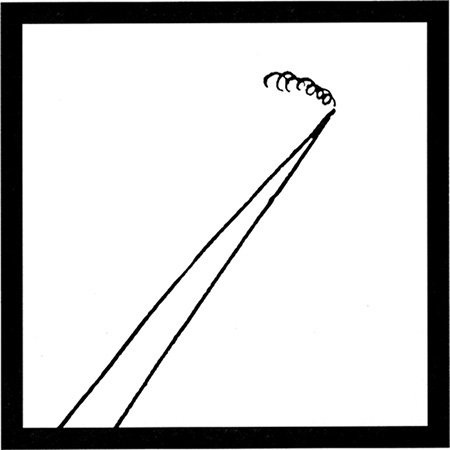

3.20 Screw Threads in Isometric

Parallel partial ellipses equally spaced at the symbolic thread pitch are used to represent only the crests of a screw thread in isometric (Figure 3.52). The ellipses may be sketched, drawn by the four-center method, or created using an ellipse template.

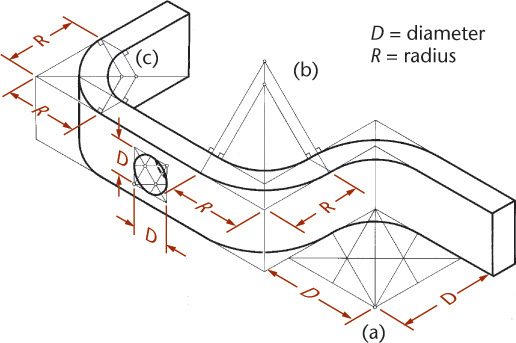

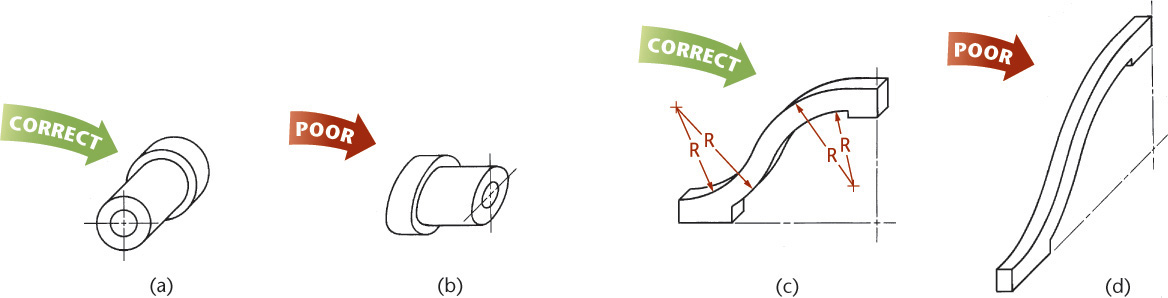

3.21 Arcs in Isometric

The four-center ellipse construction can be used to sketch or draw circular arcs in isometric. Figure 3.53a shows the complete construction. It is not necessary to draw the complete constructions for arcs, as shown in Figures 3.53b and c. Measure the radius R from the construction corner, then at each point, draw perpendiculars to the lines. Their intersection is the center of the arc. Note that the R distances are equal in Figures 3.53b and c, but that the actual radii used are quite different.

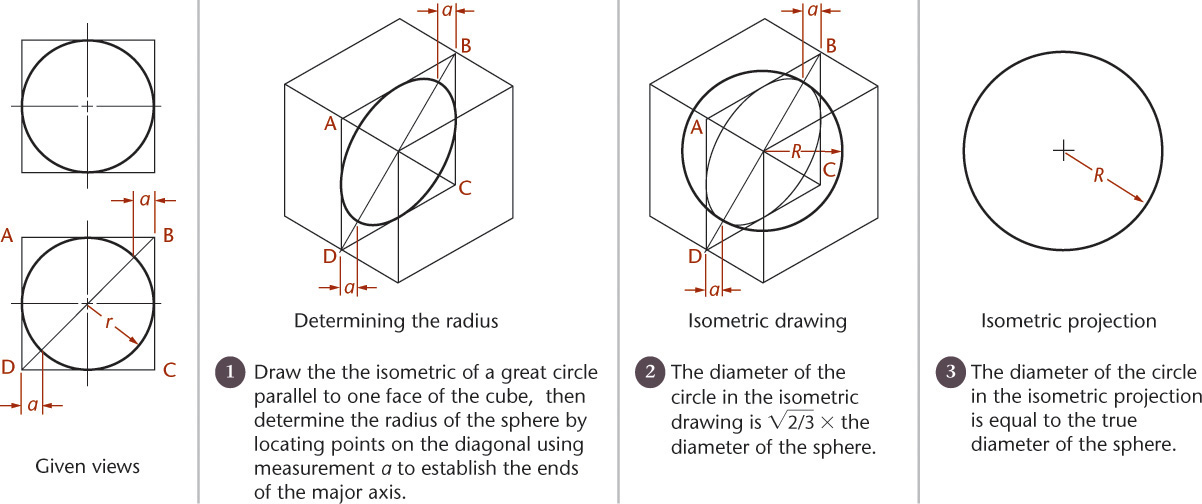

3.22 Spheres in Isometric

The isometric drawing of any curved surface can be constructed from all lines that can be drawn on that surface. For spheres, select the great circles (circles cut by any plane through the center) as the lines on the surface. Because all great circles, except those that are perpendicular or parallel to the plane of projection, are shown as ellipses having equal major axes, they enclose a circle whose diameter is the major axis of the ellipse.

Figure 3.54 shows two given views of a sphere enclosed in a construction cube. Next, an isometric of a great circle is drawn in a plane parallel to one face of the cube. There is no need to draw the ellipse, since only the points on the diagonal located by measurements a are needed to establish the ends of the major axis and thus to determine the radius of the sphere.

In the resulting isometric drawing, the diameter of the circle is ![]() times the actual diameter of the sphere. The isometric projection is simply a circle whose diameter is equal to the true diameter of the sphere.

times the actual diameter of the sphere. The isometric projection is simply a circle whose diameter is equal to the true diameter of the sphere.

3.23 Oblique Sketches

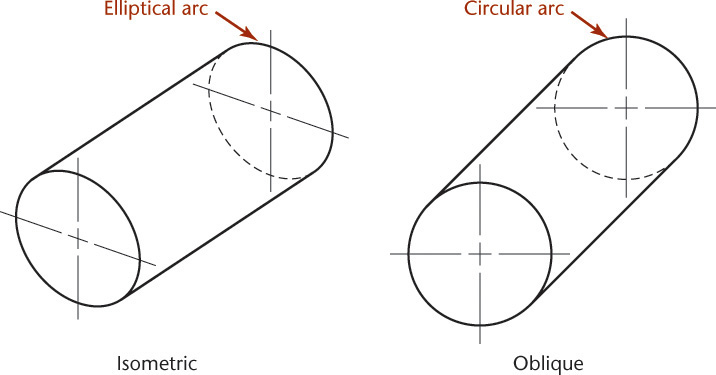

Oblique drawing is an easy method for creating quick pictorials (Figure 3.55). In most oblique sketches, circles and angles parallel to the projection plane are true size and shape and are therefore easy to construct. Although circular shapes are easy to sketch in the front oblique plane, they would appear elliptical in the top or sides. Oblique views are primarily a sketching technique used when the majority of circular shapes appear in the front view or when the object can be rotated to position circles in the front view.

CAD is not typically used to create oblique views because better-appearing isometric or perspective drawings can be created easily from 3D CAD models.

Appearance of Oblique Drawings

Three things affect the appearance of your oblique sketch:

1. The surface of the object you choose to show parallel to the projection plane

2. The angle and orientation you choose for the receding lines that depict the object’s depth

3. The scale you choose for the receding lines depicting the object’s depth (Figure 3.56)

Meat Cereals. Oblique sketching shows the front surface parallel to the view, making these meat cereal boxes easy to draw. (Courtesy of Randall Munroe.)

Choosing the Front Surface

Think about which surface of the object would be the best one to think of as parallel to the plane of projection. For example, a cube has six different surfaces. As you are creating your sketch, any of those six surfaces could be oriented as the “front” of the part. Of course, with a cube it wouldn’t matter which one you chose. But a cube with a hole through it will make a much better oblique sketch when the round hole is oriented parallel to the projection plane.

Angle of Receding Lines

An angle of 45° is often chosen for the angle of the receding lines because it makes oblique sketches quick and easy. You can use graph paper and draw the angled lines through the diagonals of the grid boxes. An angle of 30° is also a popular choice. It can look more realistic at times. Any angle can be used, but 45° is typical. As shown in Figure 3.57, you can produce different oblique drawings by choosing different directions for the receding lines.

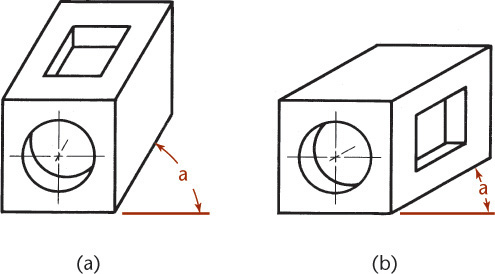

3.24 Length of Receding Lines

Theoretically, oblique projectors can be at any angle to the plane of projection other than perpendicular or parallel. The difference in the angle you choose causes receding lines of oblique drawings to vary in angle and in length from near zero to near infinity. However, many of those choices would not produce very useful drawings. Figure 3.58 shows a variety of oblique drawings with different lengths for the receding lines.

Because we see objects in perspective (where receding parallel lines appear to converge) oblique projections look unnatural to us. The longer the object in the receding direction, the more unnatural the object appears. For example, the object shown in Figure 3.58a is an isometric drawing of a cube in which the receding lines are shown full length. They appear to be too long and they appear to widen toward the rear of the block. Figure 3.59b shows how unnatural the familiar pictorial image of railroad tracks leading off into the distance would look if drawn in an oblique projection. To give a more natural appearance, show long objects with the long axis parallel to the view, as shown in Figure 3.60.

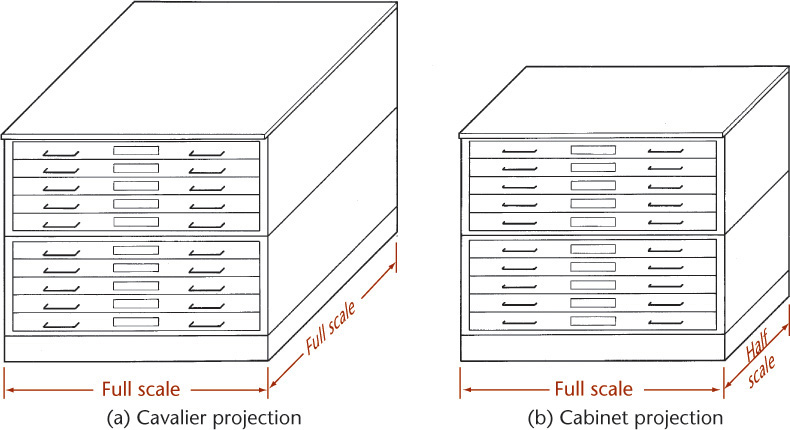

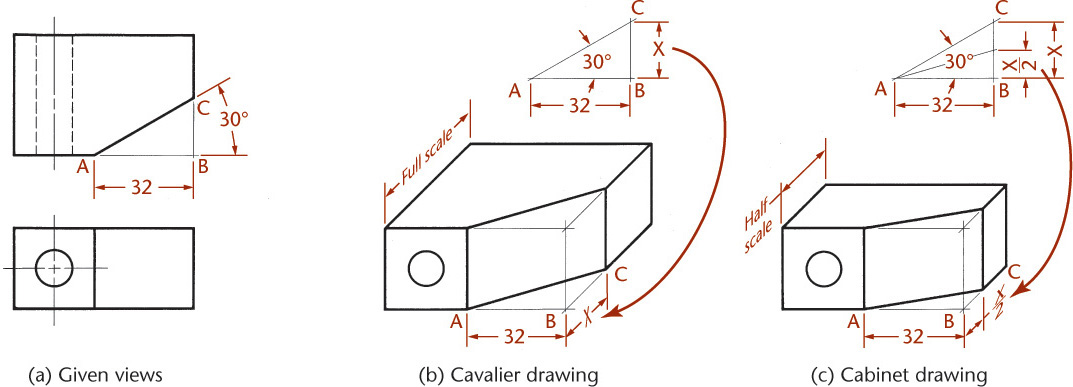

Cavalier Projection

When the receding lines are true length—(the projectors make an angle of 45° with the plane of projection)—the oblique drawing is called a cavalier projection (Figure 3.58a). Cavalier projections originated in the drawing of medieval fortifications and were made on horizontal planes of projection. On these fortifications the central portion was higher than the rest, so it was called cavalier because of its dominating and commanding position.

Cabinet Projection

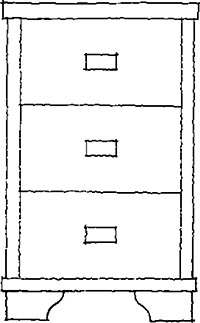

When the receding lines are drawn to half size (Figure 3.58d), the drawing is known as a cabinet projection. This term is attributed to the early use of this type of oblique drawing in the furniture industries. Figure 3.61 shows a file drawer drawn in cavalier and cabinet projections.

3.25 Choice of Position in Oblique Drawings

Orient the view so that important shapes are parallel to the viewing plane, as shown in Figure 3.62. In Figures 3.62a and c, the circles and circular arcs are shown in their true shapes and are easy to draw. In Figures 3.62b and d they are not shown in true shape and must be plotted as free curves or ellipses.

3.26 Ellipses for Oblique Drawings

Circular shapes that are parallel to the front plane of projection appear as circles in oblique view. In isometric views they appear elliptical. Figure 3.63 shows a comparison of a cylinder drawn in isometric and oblique views.

It is not always possible to orient the view of an object so that all its rounded shapes are parallel to the plane of projection. For example, the object shown in Figure 3.64a has two sets of circular contours in different planes. Both cannot be simultaneously placed parallel to the plane of projection, so in the oblique projection, one of them must be viewed as an ellipse.

If you are sketching, you can just block in the enclosing rectangle and sketch the ellipse tangent to its sides. Using CAD, you can draw the ellipse by specifying its center and major and minor axes. In circumstances where a CAD system is not available, if you need an accurate ellipse, you can draw it by hand using a four-center arc approximation.

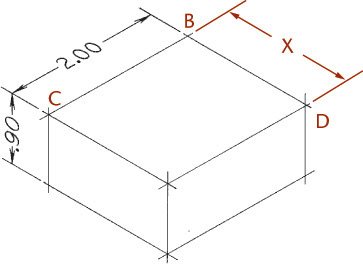

3.27 Angles in Oblique Projection

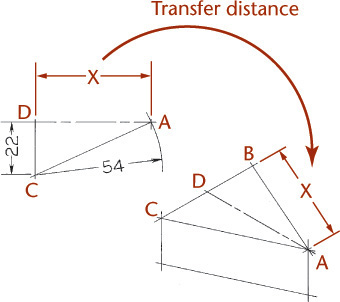

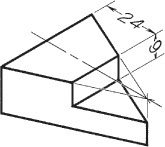

When an angle that is specified in degrees lies in a receding plane, convert the angle into linear measurements to draw the angle in an oblique drawing. Figure 3.65a shows a drawing with an angle of 30° specified.

To draw the angle in the oblique drawing, you will need to know distance X. The distance from point A to point B is given as 32 mm. This can be measured directly in the cavalier drawing (Figure 3.65b). Find distance X by drawing the right triangle ABC (Figure 3.65c) using the dimensions given, which is quick and easy using CAD.

You can also use a mathematical solution to find the length of the side: The length of the opposite side equals the tangent of the angle times the length of the adjacent side. In this case, the length of the opposite side, X, is about 18.5 mm. Draw the angle in the cavalier drawing using the found distance.

Remember that all receding dimensions must be reduced to match the scale of the receding axis. In the cabinet drawing in Figure 3.65c, the distance BC must be half the side BC of the right triangle in Figure 3.65c.

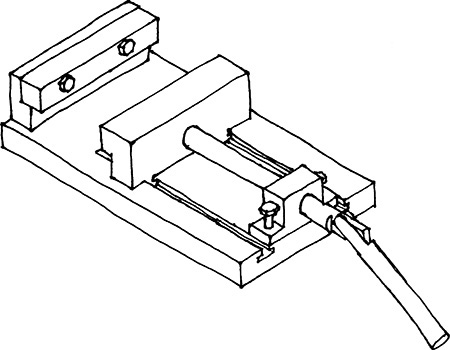

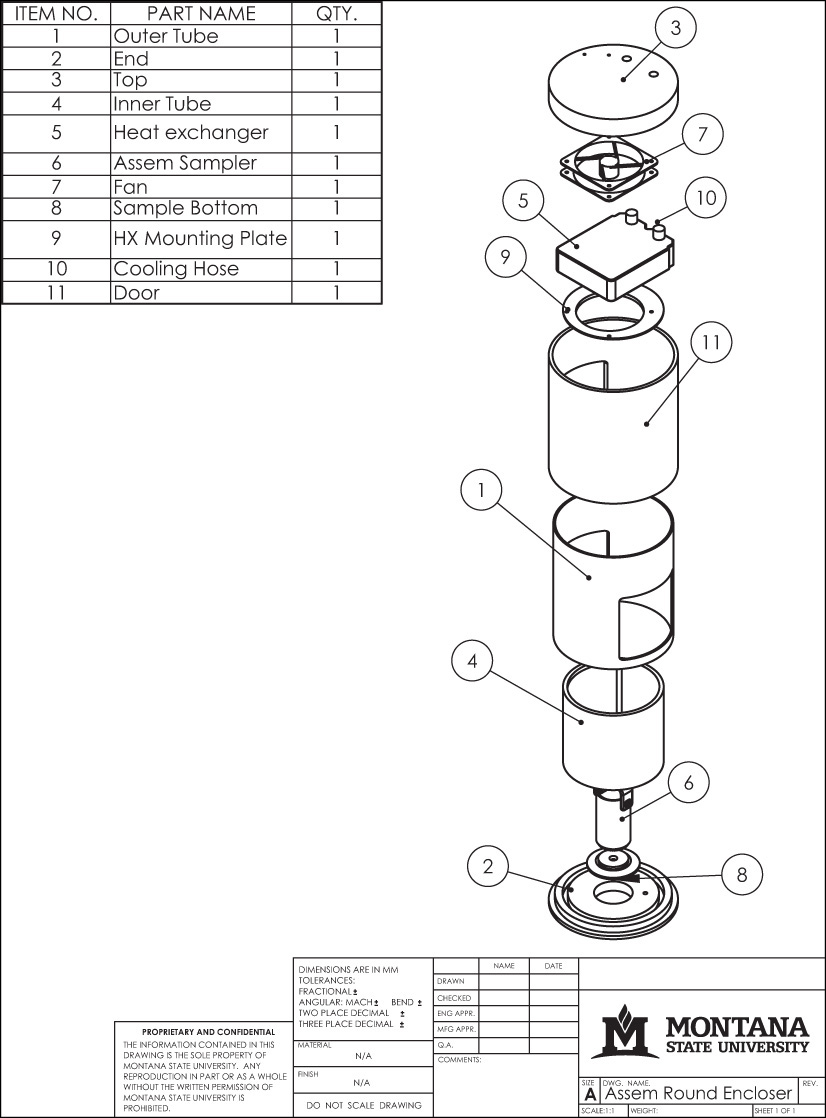

3.28 Sketching Assemblies

Assembly drawings are used to show how parts fit together. Because they do not need to provide all the information to make individual parts, isometric sketches or drawings are often used that show only the exterior view of the assembled parts. You can use assembly sketches as you design to identify areas that must fit together or have common dimensions, or to maintain critical distances to ensure that the device will function as expected. Figure 3.66 shows an isometric sketch of an assembly.

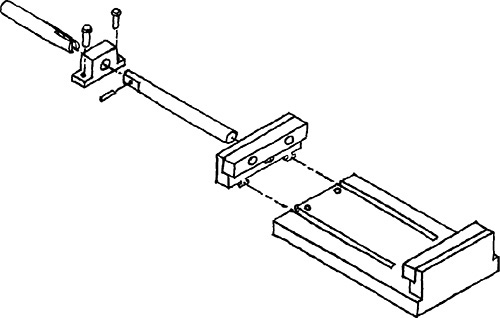

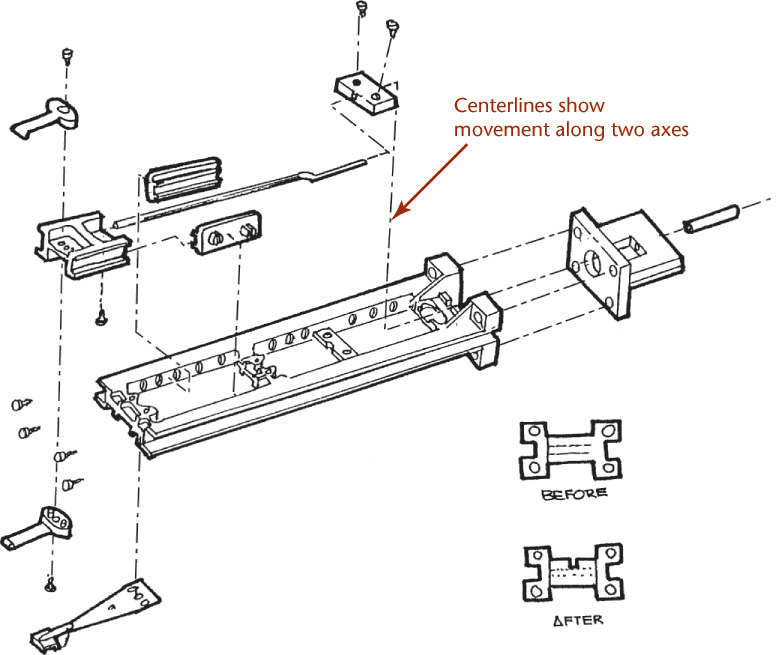

Sketched assembly drawings are useful in documenting your ideas in a rougher state. An exploded isometric assembly drawing shows the individual parts moved apart from one another along the isometric axis line directions. A centerline pattern is used to show how the parts relate and fit together.

When creating an exploded assembly sketch, keep the parts lined up with the other parts where they assemble. If possible, move any single parts along only one axis direction. In Figure 3.67, all exploded parts are moved along only one axis direction. Notice the centerline pattern showing how the parts align. If you must move a part in two different directions so that it can be seen clearly, add a centerline showing how the part must move to get to its proper location in the assembly. In Figure 3.68, parts have been moved in two axis directions. You can see the jog in the centerline indicating how the part has been moved.

3.67 Exploded Isometric Assembly Sketch. Centerlines have been added to show where parts line up in the assembly.

3.68 Isometric Assembly Sketch. Some parts have been exploded in two directions so they do not overlap other parts in the assembly. The centerlines indicate the path the part must follow to assemble correctly. (Courtesy of Albert W. Brown, Jr.)

Finished assembly drawings that will be given to manufacturing workers to show them how to produce a device also contain a parts list that identifies each part in the assembly, the quantity necessary, the material of each part, and a number identifying which item it is on the drawing. A parts list can also be included on a sketched assembly drawing. Sometimes it is helpful to give a quick assembly sketch to manufacturing along with part drawings, especially if they are parts you need to have manufactured quickly from a sketch. Seeing how the parts fit together in assembly will help the manufacturer understand the entire device and identify potential problems.

3.29 Sketching Perspectives

Perspective pictorials most closely approximate the view produced by the human eye. Perspective views are the type of drawing most like a photograph. Examples of a perspective drawing can be seen in Figures 3.69, 3.70a, and 3.72. Although complex perspective views are time consuming to sketch, they are easy to create from 3D CAD models.

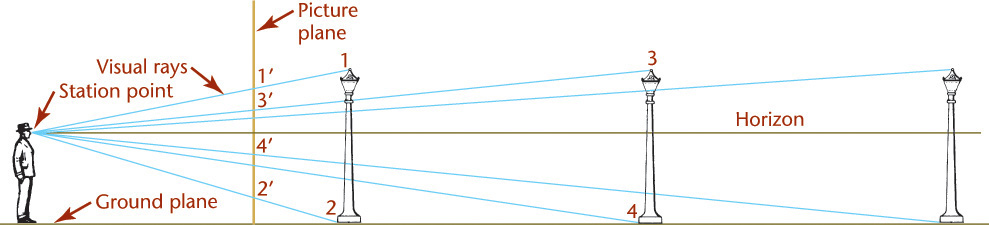

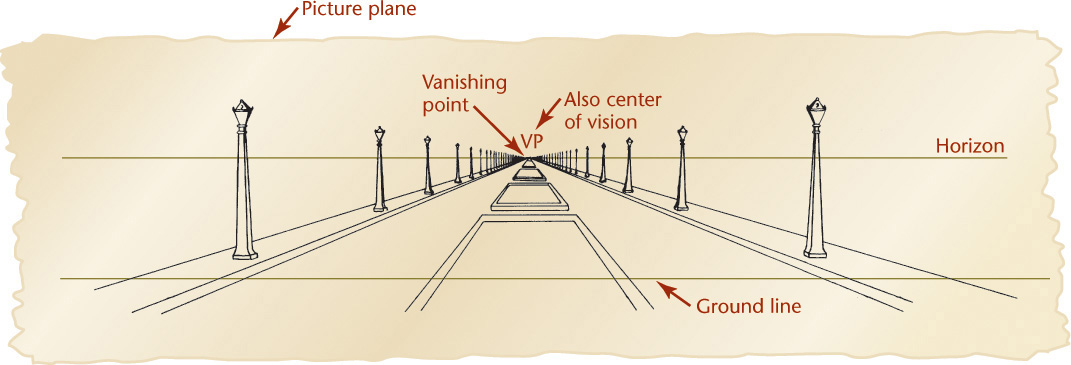

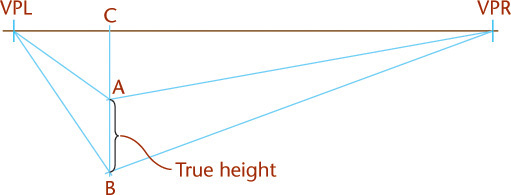

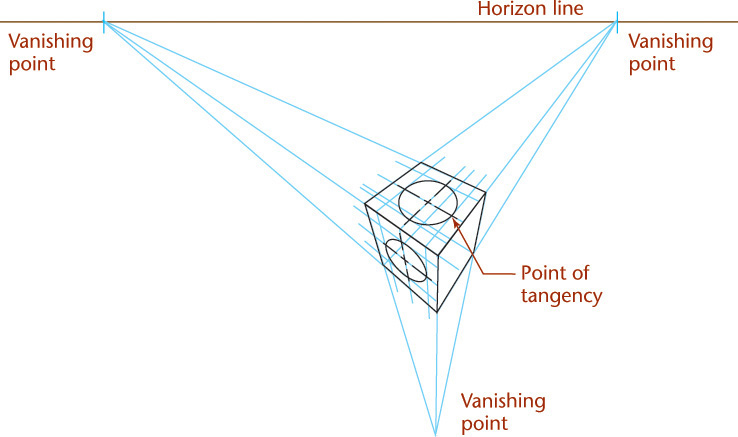

Unlike parallel types of projection, perspective projectors converge. The point at which the projectors converge is called the vanishing point. This is clearly seen in Figure 3.70a.

The first rule of perspective is that all parallel lines that are not parallel to the picture plane vanish at a single vanishing point, and if these lines are parallel to the ground, the vanishing point will be on the horizon. Parallel lines that are also parallel to the picture plane remain parallel and do not converge toward a vanishing point (Figures 3.71 and 3.72).

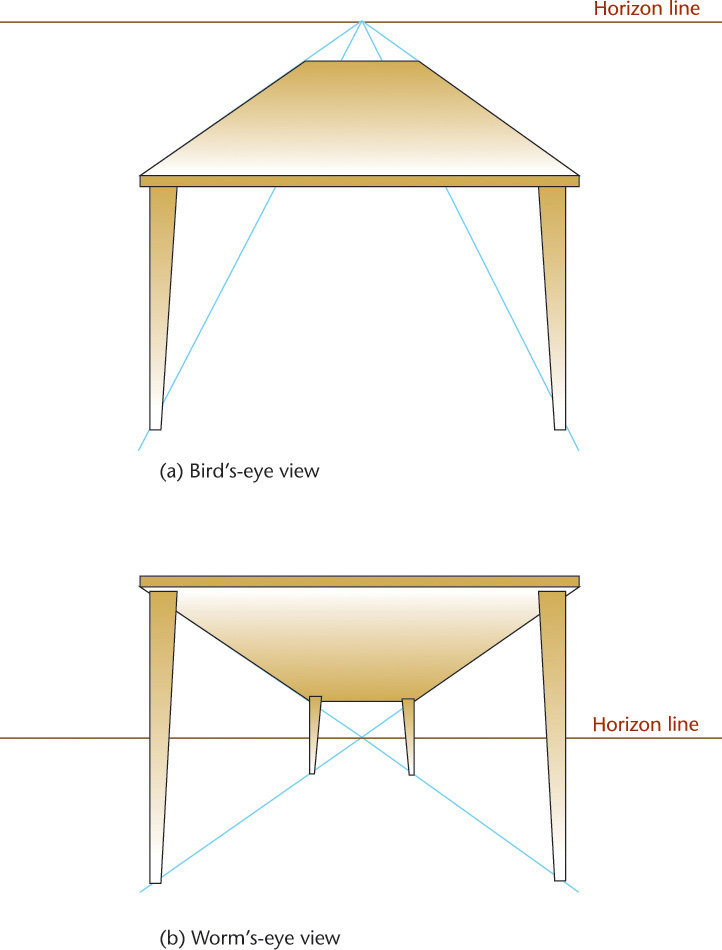

When the vanishing point is placed above the view of the object in the picture plane, the result is a bird’s-eye view, looking down onto the object. When the vanishing point is placed below the view of the object, the result is a worm’s-eye view looking up at the object from below (see Figure 3.74 on page 107).

There are three types of perspective: one-point, two-point, and three-point perspective, depending on the number of vanishing points used.

The Three Types of Perspective

Perspective drawings are classified according to the number of vanishing points required, which in turn depends on the position of the object with respect to the picture plane.

If the object sits with one face parallel to the plane of projection, only one vanishing point is required. The result is a one-point perspective, or parallel perspective.

If the object sits at an angle with the picture plane but with vertical edges parallel to the picture plane, two vanishing points are required, and the result is a two-point perspective, or an angular perspective. This is the most common type of perspective drawing.

If the object sits so that no system of parallel edges is parallel to the picture plane, three vanishing points are necessary, and the result is a three-point perspective.

One-Point Perspective

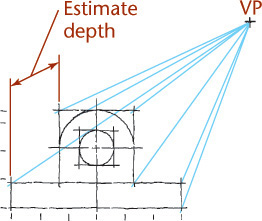

To sketch a one-point perspective view, orient the object so that a principal face is parallel to the picture plane. If desired, this face can be placed in the picture plane. The other principal face is perpendicular to the picture plane, and its lines will converge toward a single vanishing point.

8:12 Train as Seen by 8:12 1/2 Commuter (Excerpted from Droodles – The Classic Collection by Roger Price ©2000 by Tallfellow Press. Used by permission. All rights reserved.)

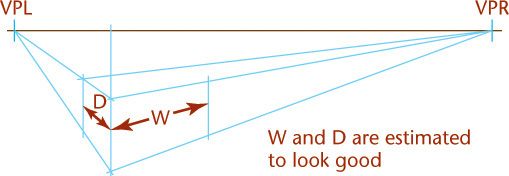

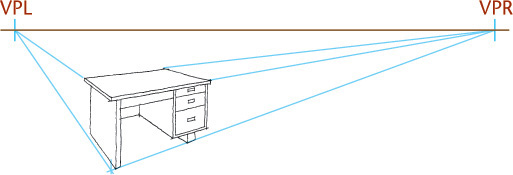

Two-Point Perspective

Two-point perspective is more true to life than one-point perspective. To sketch a two-point perspective, orient the object so that principal edges are vertical and therefore have no vanishing point; edges in the other two directions have vanishing points. Two-point perspective is especially good for representing buildings and large civil structures, such as dams or bridges.

Three-Point Perspective

In three-point perspective, the object is placed so that none of its principal edges is parallel to the picture plane. Each of the three sets of parallel edges has a separate vanishing point. See Figure 3.73.

Bird’s-Eye View versus Worm’s-Eye View

The appearance of a perspective sketch depends on your view-point in relation to the object. Select some reachable object in the room and move so that you are looking at it from above and really notice its shape. Now gradually move so that you are looking at it from below. Notice how the change of viewpoint changes the appearance of its surfaces—which ones are visible and their relative size.

The horizon line in a perspective sketch is a horizontal line that represents the eye level of the observer. Locating the sketched object below the horizon line produces a view from above (or a bird’s-eye view). Locating the sketched object above the horizon line produces a view from below (or a worm’s-eye view). Figure 3.74 illustrates the horizon line in a drawing and the effect of placing the object above or below the horizon line.

3.30 Curves and Circles in Perspective

If a circle is parallel to the picture plane, its perspective view is a circle. If the circle is inclined to the picture plane, its perspective drawing may be any one of the conic sections in which the base of the cone is the given circle, the vertex is the station point, and the cutting plane is the picture plane (see Figure 3.71). The centerline of the cone of rays is usually approximately perpendicular to the picture plane, so the perspective will usually be an ellipse.

An ellipse may be drawn using a method of blocking in its center and a box tangent to the ellipse as shown in Figure 3.75. Also shown is a convenient method for determining the perspective of any planar curve.

3.31 Shading

Shading can make it easier to visualize pictorial drawings, such as display drawings, patent drawings, and catalog drawings. Ordinary multiview and assembly drawings are not shaded. The shading should be simple, reproduce well, and produce a clear picture. Some of the common types of shading are shown in Figure 3.76. Two methods of shading fillets and rounds are shown in Figures 3.76c and d. Shading produced with dots is shown in Figure 3.76e, and pencil tone shading is shown in Figure 3.76f. Pencil tone shading used in pictorial drawings on tracing paper reproduces well only when making blueprints, not when using a copier.

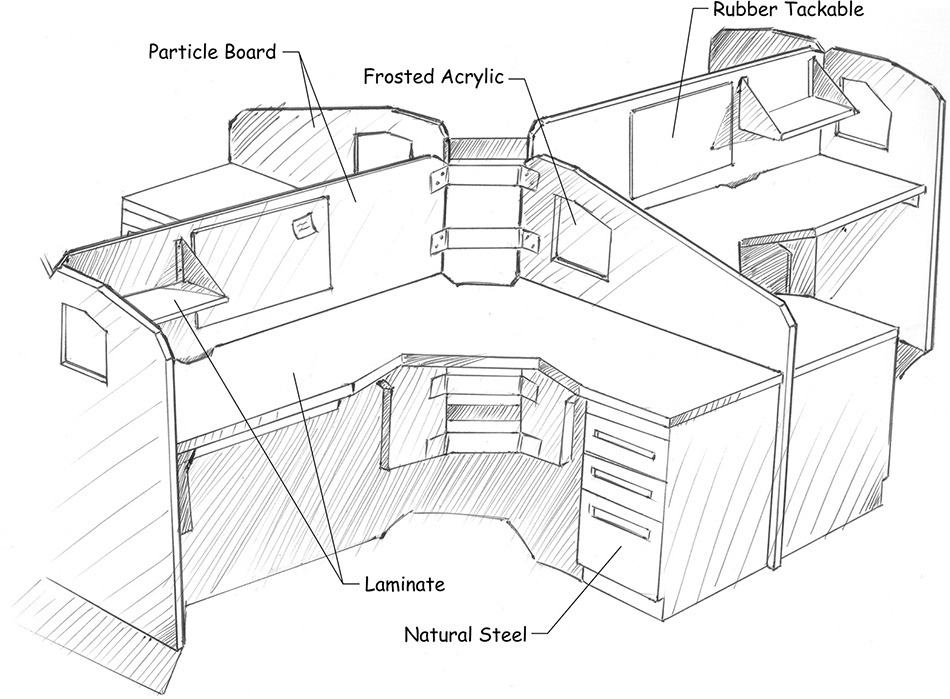

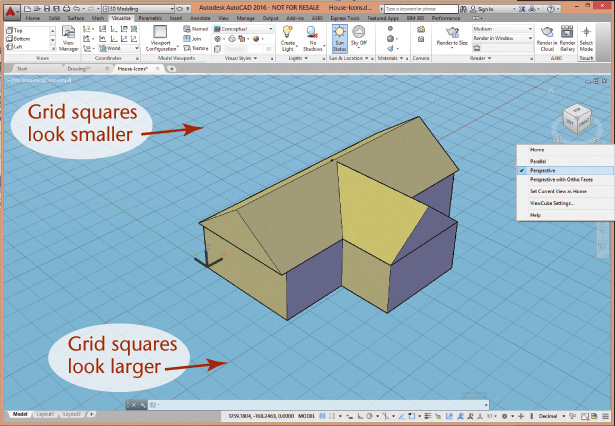

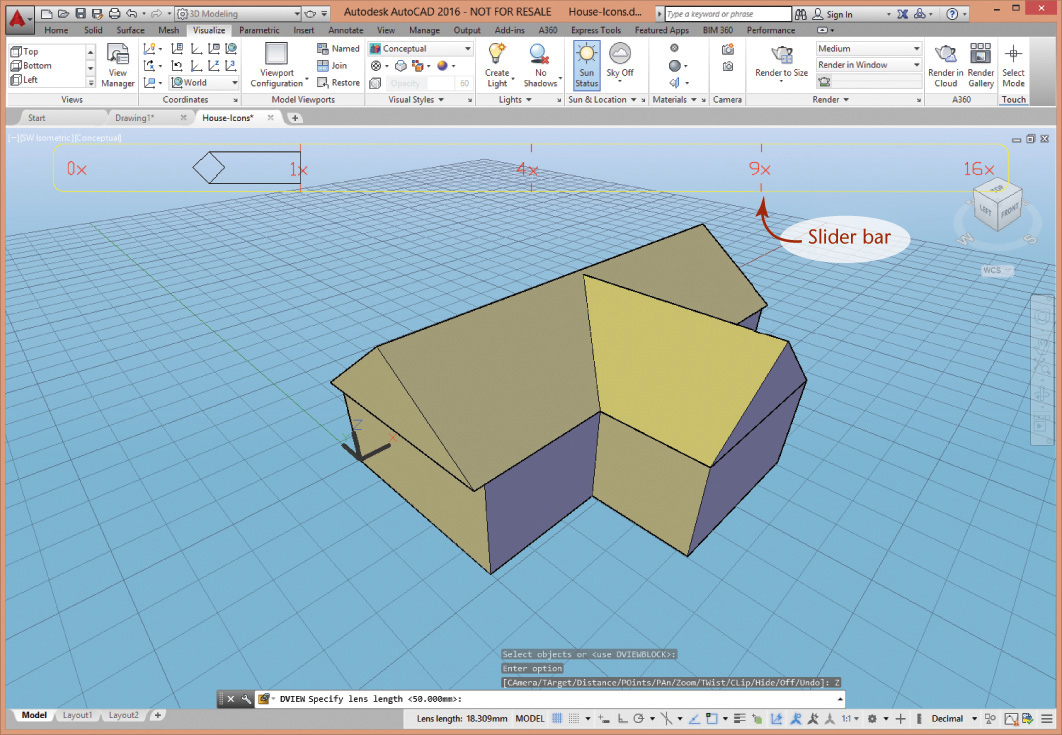

3.32 Computer Graphics

Pictorial drawings of all types can be created using 3D CAD (Figures 3.77 and 3.78). To create pictorials using 2D CAD, use projection techniques similar to those presented in this chapter. The advantage of 3D CAD is that once you make a 3D model of a part or assembly, you can change the viewing direction at any time for orthographic, isometric, or perspective views. You can also apply different materials to the drawing objects and shade them to produce a high degree of realism in the pictorial view.

3.33 Drawing on Drawing

Because CAD helps people produce accurate drawings that are easy to alter, store, and repurpose, computer automation has made the painstaking aspects of hand-rendering technical drawings nearly obsolete. Still, the ability to sketch with clarity is an immediate and universal way to record and communicate ideas.

The ability to think of complex objects in terms of their basic solid components and to identify relationships between various surfaces, edges, and vertices is basic to creating both hand-drawn (Figure 3.79) and computer-generated technical drawings. By understanding how to represent objects accurately, you can communicate efficiently as part of a team and increase your constructive visualization ability, or your ability to “think around corners.”

3.79 Hand Sketch Conveying Custom Workstation Furniture Concept (Courtesy of Jacob A. Baron-Taltre.)

Chapter Summary

• Sketching is a quick way of visualizing and solving a drawing problem. It is an effective way of communicating with all members of the design team.

• Three-dimensional figures are bounded by surfaces that are either planar, single-curved, double-curved, or warped.

• Prisms, pyramids, cylinders, cones, tori, and ellipsoids are common shapes in engineering drawings. There are also five regular polyhedra: the tetrahedron, hexahedron, octahedron, dodecahedron, and icosahedron.

• There are special techniques for sketching lines, circles, and arcs. These techniques should be practiced so they become second nature.

• Using a grid makes sketching in proportion an easy task.

• Circles can be sketched by constructing a square and locating the four tangent points where the circle touches the square.

• A sketched line does not need to look like a CAD or mechanical line. The main distinction between CAD and instrumental drawing and freehand sketching is the character or technique of the line work.

• Freehand sketches are made to proportion, but not necessarily to a particular scale.

• Sketching is one of the most important skills for accurately recording ideas.

• Isometric, oblique, and perspective are three methods used to create pictorial sketches.

Review Questions

1. What are the advantages of using grid paper for sketching?

2. What is the correct technique for sketching a circle or arc?

3. Sketch the alphabet of lines. Which lines are thick? Which are thin? Which are very light and will not reproduce when copied?

4. What type of pictorial drawing can easily be drawn on square grid paper?

5. What is the advantage of sketching an object first before drawing it using CAD?

6. What is the difference between proportion and scale?

Sketching Exercises

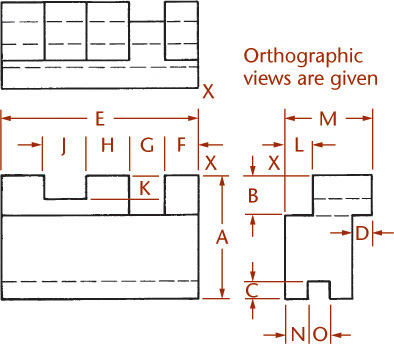

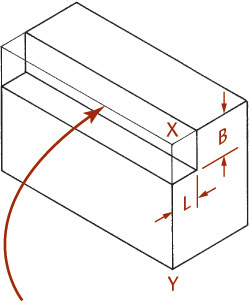

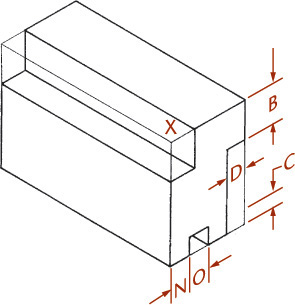

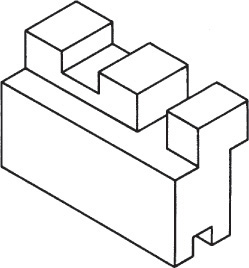

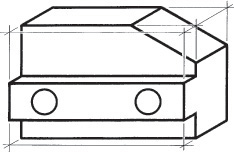

Exercise 3.1 Sketch the objects shown using isometric, oblique, and one- or two-point perspective.

1. Practice the sketching skills and techniques you have learned for construction lines and ellipses. Set a timer for 10 minutes and make quick sketches of these nine different containers.

2. Select one container and create isometric, oblique, and perspective drawings.

3. Design a new piece of drinkware, using your sketching skills.

4. Select one container. Draw an enclosing box and shade in the negative space so that the contour of the container remains white.

Exercise 3.3 Quick Sketch. Practice the sketching skills and techniques you have learned for construction lines and ellipses. Set a timer for 10 minutes and make quick sketches of these six different chairs.

Exercise 3.4 Quick Sketch. Practice the sketching skills and techniques you have learned for construction lines and ellipses. Set a timer for 10 minutes and make quick sketches of these tools.

Exercise 3.5 Sketching. Practice the sketching skills and techniques you have learned for construction lines and ellipses. Set a timer for 10 minutes and make quick sketches of these items.

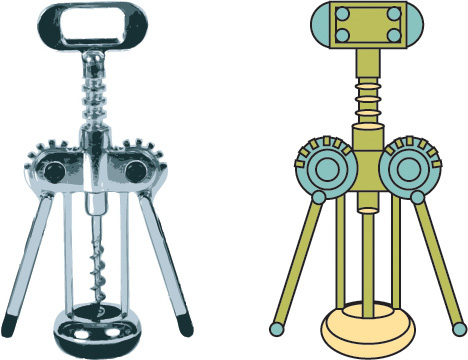

Exercise 3.6 Parking Meter. Create an oblique pictorial sketch of the parking meter shown here. Use construction lines to keep the features in proportion.

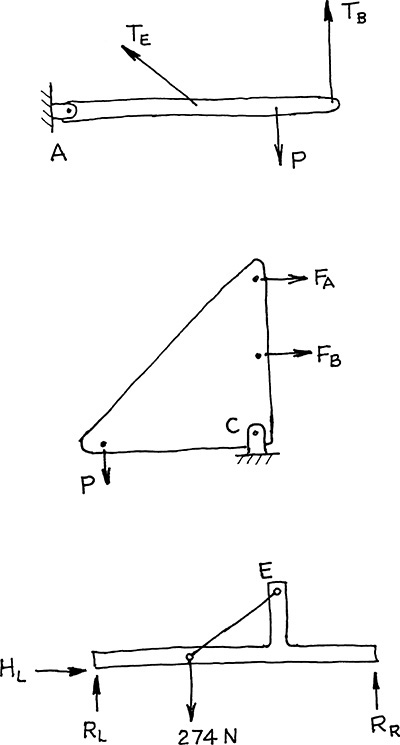

Exercise 3.7 Free-Body-Diagram Sketches. Sketch the free body diagrams as shown.

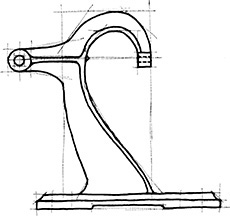

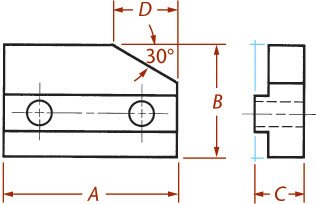

Exercise 3.8 Rocker Arm. Create a freehand sketch. Use the dimensions to help in estimating proportions. Leave the dimensions off your sketch unless directed otherwise by your instructor.

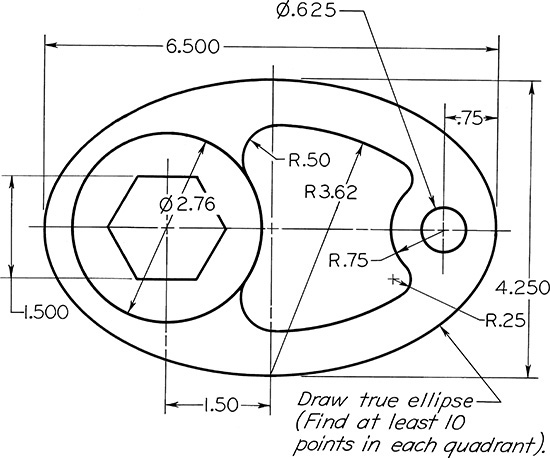

Exercise 3.9 Special Cam. Create a freehand sketch. Use the dimensions to help in estimating proportions. Leave the dimensions off your sketch unless directed otherwise by your instructor.

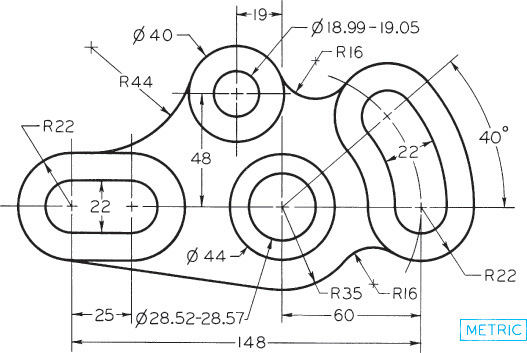

Exercise 3.10 Boiler Stay. Create a freehand sketch. Use the dimensions to help in estimating proportions. Leave the dimensions off your sketch unless directed otherwise by your instructor.

Exercise 3.11 Outside Caliper. Create a freehand sketch. Use the dimensions to help in estimating proportions. Leave the dimensions off your sketch unless directed otherwise by your instructor.

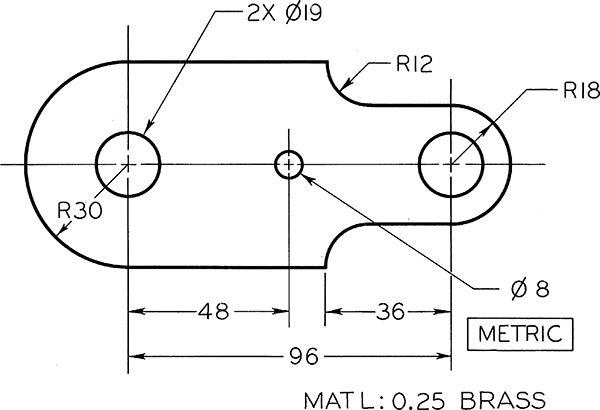

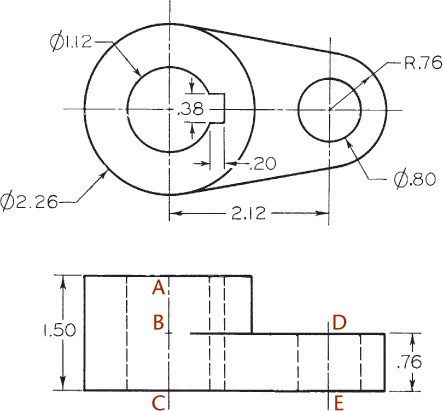

Exercise 3.12 Gear Arm. Create a freehand sketch. Use the dimensions to help in estimating proportions. Leave the dimensions off your sketch unless directed otherwise by your instructor.

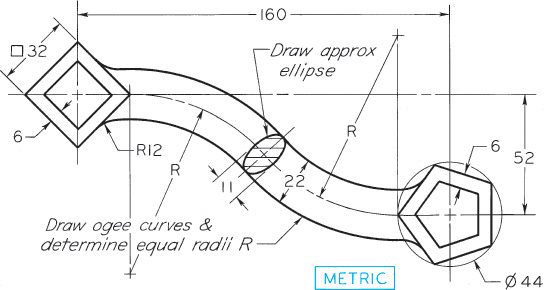

Exercise 3.13 Special S-Wrench. Create a freehand sketch. Use the dimensions to help in estimating proportions. Leave the dimensions off your sketch unless directed otherwise by your instructor.