4 motion graphics in the environment

an overview

we live in a time and culture where all of our sensory experiences are challenged by the bombardment of information. The potential of motion graphics in our physical world has finally been realized and is helping to shape the landscape of environmental interior and exterior design. Public informational systems, performance art, memorial and donor recognition programs, and contemporary video installations are vehicles that have opened new doors for motion graphic designers.

“what made view I people stop painting frescoes and start painting on panels and stretched canvases anyway? And what if corporations moved away from fixed logo-type signage on the outside of their building facilities and put big video screens up there instead?”

—Terry Green, twenty2product

New Technologies

Digital technologies are playing a much greater role in shaping our visual, public landscape. Video wall systems, which can display very large images without compromising screen resolution, are thriving throughout the world in almost every arena, including trade shows,shopping malls, corporate lobbies, casinos, showrooms, nightclubs, retail stores, restaurants, and sports arenas. Pier 39, located in Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco, is visited by millions of affluent consumers annually. As a prime target for advertisers, they experience a 9’ × 15’ video wall, developed and installed by San Francisco Outdoor Tv. The LED screen operates seven days, featuring headline news and sports programs, weather, and trivia in San Francisco and the Bay Area.

A major benefit of video wall architecture is that it is scalable and interchangeable, allowing many screen sizes and horizontal or vertical configurations. The X-Wall, for example, is designed specifically for the expanding requirements for large scale visualization and presentation systems. Another advantage is that as a video wall’s size increases, the number of available pixels (resolution) and overall brightness per square foot remains constant. (This is not true of projection systems.) A 2’ × 2’model, for example, involves four monitors or cubes to be placed side-by-side on top of another two. The configurations can grow to 3’ × 3’, 4’ × 4’ and so forth.

Media critics believe that video wall technology will continue developing along with the demands of more sophisticated public entertainment and information systems.

Over the past decade, advanced display technologies have used light to transform public spaces, build brands, and invoke imagination by allowing motion graphics to become a physical part of our environment. Large companies, such as Daktronics—one of the world’s largest suppliers of large screen video displays and electronic scoreboards—are trendsetting in the sphere of Light Emitting Diodes (LED) technology. LED lighting systems have increasingly become the choice of architects and designers who are transforming environments with “intelligent light.” Unlike traditional “flat” LCD or plasma displays, LEDs can be customized to any size and aspect ratio, allowing many possible geometric configurations. These displays are manufactured with perfectly square corners, having little or no seams apparent between modules to allow seamless configurations of content. Another advantage of LED displays is that they are visible in front windows, since they are bright enough to compete with sunlight. They can also have viewing distances less than 3 feet, since the pixels are densely placed.

Immersive Environments

Immersive environments shape a sense of place by providing order, ambience, comfort, and insight to a physical or virtual space. They are a unique confluence of architecture, interior design, images, motion graphics, and sound that operate holistically to provide aesthetic, meaningful experiences and enhance social interaction. They are also used to communicate products, services, or messages by merging interactive digital technologies with tangible and physical spatial experiences. Today immersive environments are designed to blend physical and imaginary worlds in which moving images, text, and audio can respond to humans. The artistic and expressive qualities of animation is appearing more frequently in hotel lobbies, trade shows, retail spaces, and museums, as well as in complex public environments such as airports and theme parks.

Historical Perspective

During the 1920s, French film director Abel Gance experimented with a three screen version of Napolcon. In the 1960s, Cinemascope’s elongated proportion was extended by Cinerama to a concave screen that curved to embrace audiences. The New York World’s Fair of 1964 marked the apotheosis of the giant screen frenzy. Pavilions competed for the most breathtaking displays: the circular Kodak theater, the GE “sky-dome spectacular,” General Cigar’s “Movie in the Round,” and Charles and Rac Eames’ “View from the People Wall,” a nine screen projection on the ceiling of the IBM building. These were the precursors to today’s IMAX theaters.

During the 1970s, multiimage slide projectors allowed multiple, dissolving images to be displayed in an array of wide ratios. Those slide shows also relied heavily on film processing, glass mounting, and slide tray loading. Electronic imaging surfaced in the mid 1980s. The slide screen was put aside for video wall monitors and new, exciting possibilities of video display technology. During the 1990s, dignal processing and high-resolution projection cubes were developed to compete with brighter projector technologies. By this time, video walls were so popular that all kinds of companies were joining the production arena.

The concept, design, and fabrication of immersive environments must take into account how information is perceived and processed by an audience, the application of graphic style to the information, and (he needs of diverse audiences-including individuals with physiological and cognitive disabilities. Color, typography, composition, and movement must also be considered in order to communicate information clearly, concisely, and consistently.

interior design

The infusion of motion graphics into interior spaces has become a vital component in establishing mood and atmosphere. In corporate lobbies or waiting rooms, for example, they can be used to reinforce a brand, change content to support various messages, and define an ambiance that might be unattainable with other mediums, while maintaining the design integrity of the space. Motion graphics in retail and event spaces can add a unique dimension to the space, provide drama and suspense in entranceways, attract outside traffic by presenting the content in display windows, and support a product theme or a brand. Casinos, restaurants, and hotels have also used motion graphics to create engaging immersive experiences for patrons, provide conversation pieces to stimulate guest interaction, and provide unique content as a substitute to mundane television programming.

Spanning across the width of the lobby of Nielsen Media Research’s head office in NewYork, a row of ten projection screens plays video presentations that are looped throughout the day (4.1 and 4.2). The architect who designed the lobby chose rear projection (versus plasma) screens, allowing them to line up seamlessly without any frames around them. For exhibition and convention projects of this nature, it is challenging to predict how the video will look large-scale, since the wall may not actually be implemented until after the content is designed. (In this case, the wall was built just two weeks before the opening.) Additionally, the wall’s large size made it difficult to gauge how it would look in the lobby just by watching a small preview movie.

A video installation for John Levy, an international lighting design firm headquartered in Los Angeles, was used inside several casinos with the simple goal of providing entertainment for the casino’s patrons. The installation consisted of five 15’ tall screens. The motion graphics composition, entitled “Lava,” was an amalgamation of various beach scenes including surfing, underwater imagery, and water sports (4.2).

4.2 Frames from a looped video installation for Nielsen Media Research’s head office.

4.3 Frames from “Lave.” Courtesy of Reality Check Studios.

In 2004, Imaginary Forces designed a permanent video installation for the lobby of New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The installation randomly selects artworks from the museum’s collection and animates them on nine 30″ screens in tandem with changing content on events and exhibitions to provide both information and ambience. The system architecture, consisting of high definition LCD monitors and a network of ten computers, algorithmically selects from a repertoire of images and action sequences, such as fast blurring, slow scaling, and cross-fading and applies them to the screens. The museum updates the system with text and new images of temporary shows and the permanent collection on a regular basis, so that the content always changes. According to Kurt Ralske, who designed and implemented the system and co-designed the image sequences, the original idea for the installation involved playing back video from a hard drive. Because of the amount of data needed to display the content at high resolution, the use of still images in motion could be created by moving, transforming, scaling, and blending them in real-time (4.4).

4.4 MoMA display screens, 2004. Courtesy of Imaginary Forces.

In addition to the use of flat screens, many animated interior designs have utilized curved LED displays. For example, Radio Shack’s corporate headquarters in downtown Fort Worth, Texas utilizes a circular configuration of LED displays to line the 64’ interior circumference of its rotunda (4.5). Each screen measures 4’ high × 22’ in diameter. A combination of vivid live-action and graphic content, theatrical lighting, and sound gives patrons a distinctive, sensory experience and conveys Radio Shack’s dominance in the consumer electronics market. The Grand Court at the Mall at Millennia in Orlando, Florida houses a circle of twelve, freestanding LED displays that represent the Neolithic majesty of Stonehenge (4.6). The screens are thrust 30’ in the air, each measuring 10’ high × 4’ wide with a 40° arc. Since they can be viewed from behind, the cosmetic appearance of the rear surfaces had to be aesthetically pleasing and continuous. This celebration of American consumerism on a grand scale provides an entertaining, informative environment for its patrons.

4.5 The rotunda at Radio Shack’s corporate headquarters in Fort Worth,Texas. Photo courtesy of Daktronics, Inc.

4.6 LED displays at the Grand Court at the Mall at Millennia in Or lando, Florida. Photo courtesy of Daktronics, Inc.

The cosmetic amearance of the Executive Suite at Goldman Sachs’ global headquarters is enlivened with a digital media installation that features a rich display of live data reflecting the firm’s visionary technological innovations, industry knowledge, and global insights. This compelling communication experience shares Goldman Sachs’ position in the world financial markets in an instantaneous and sophisticated way that engages their executive staff and impresses

their visitors. Unified Field, a privately held media design company in New York City, implemented their “Evolving Screen” technology to transform this public space into “living architecture” by providing a self-evolving movie that interweaves the history, culture, and people of Goldman Sachs with current events, global financial data, and news in a virtual 3D landscape. The information—which takes on many forms including live footage, text, images, real time news, data feeds, and data-driven 4D models—continually changes in response to market and business activities, ranging from trading patterns of individual stocks to informed decisions of personnel worldwide (4.7).

4.7 Frames from the screens at the Executive Suite of Goldman Sachs’ global headquarters. Courtesy of Unified Field, Inc.

Billijam, a video art and motion graphics company in NewYork City specializes in creating distinctive animation sequences that bring life and culture to public spaces that require ambiance enhancement (4.8). Founded by entrepreneurs Marya Triand and Pat Lewis, the company has helped define brands in the hotel industry by providing aesthetic, immersive environments that can be displayed on plasma screens or be projected onto almost any surface. Additionally, they can be timed to generate different ambiences for patrons throughout the day. Marya’s captivating work has been displayed in settings such as The Times Square Hilton, the Marriott Marquis, the New York Barclay Hotel, Hotel 41, Club Avalon, and the Remote Lounge.

4.8 Marya Triand’s dynamic animation sequences are imbued with colorful and textural video and graphic images to create ambient environments for public spaces. Courtesy of Billijarn.

4.9 Frames from a community video wall for Washington Mutual’s Manhattan retail space. Courtesy of twenty2product. Copyright 2003 Washington Mutual, all rights reserved.

exhibit design

Today, the field of exhibit design combines graphic design, interactive media, motion graphics, and product design. Exhibit designers typically have backgrounds that include a variety of disciplines, such as industrial design, architecture, interior design, graphic design, and theatrical design. They must demonstrate strong creative skills and sensitivity to basic aesthetic principles, such as color, composition, and perspective, as well as a knowledge of materials, lighting, and the ability to work independently or as part of a team.

An imaginative, well-designed exhibit creates a memorable and lasting impression on its viewers. Its success is judged by the effectiveness in which its content meets the aesthetic and spatial requirements of a site. The design must incorporate the essence of the individual products or brands being featured, while tying them into a cohesive, unified environment. Other considerations involve the creative use of lighting and architectural elements such as stairways, lounges, reception desks, entranceways, conference rooms, flooring, ceilings, walls, and so forth. Further, materials can range from sand and tree bark to synthetic materials such as translucent concrete or fiberglass.

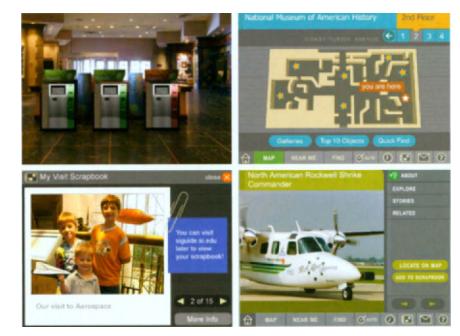

The Samsung Experience, located on the third floor of The Shops at Columbus Circle in the Time Warner Center, is one of the strongest examples of digital convergence in an immersive environment. A remarkable 10,000-square-foot interactive emporium of virtual reality experiences and technology integrates various technologies to demonstrate to visitors how Samsung’s brand and latest products can enrich everyday life. (Samsung’s partners, including MIT Media Lab, Parsons School of Design, Napster, and Sprint PCS, are featured.) As an educational resource, this seamless world of sights, sounds, and sensations communicate the life-enhancing benefits of digital technology without the pressures of a sales environment. Giant rotating LCD screens feature interconnected virtual worlds. Interactive workstations allow users to create digital collages in real time. In the space outside of the Samsung Experience is an interactive map of Manhattan that can be viewed and manipulated with hand gestures, facilitating a user’s experience of digital lifestyle in NewYork. Of particular interest is The Cyber Brand Showcase, a participatory Web site that blurs the boundary between real and virtual space by allowing visitor information to be exchanged between the physical environment and the online environment through cyber conduits.

Elan was the premier sponsor of the 9th International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease at the Pennsylvania Convention Center in Philadelphia. KSK:STUDIOS hired a environmental designer, Adrian Levin, to design the booth, and a branding specialist, Anita Zeppetelli, to establish the visual identity for the convention. Video signage was presented on six plasma screens that were installed around the main tower. Instead of playing the same video on all six screens, a computerbased video device allowed six independent streams of video to be displayed in sync, so that elements could move all across the screens. The most challenging aspect of this project was that the screens were configured in a hexagonal arrangement, meaning that the video could have no discrete ends horizontally. Within a 3D program, six cameras were aimed at the same objects from different angles (4.10).

4.10 Exhibit design for an International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease. Courtesy of Dyske Suematsu and KSK:STUDIOS.

BrainLAB, a German medical technolorn company, showcased their orthopedic products at a trade show convention screens that were configured in a row, each repreusesnintgin tg-w ae lsv-pee cpil faiscm a screens that were configured in a row, each repreusesnintgin aspecific product (4.11). Rather than playing independent videos simultaneously, they wanted certain elements to move across the screens. At KSK:STUDIOS, Dyske Suematsu designed the motion graphics and harnessed a computer-based video server to play twelve streams of video in sync. Since the screens had to act as one, the dimensions of the original design were enormous (10,368×486 pixels to be exact).

4.11 Installation for BrainLAB. Courtesy of Dyske Suematsu and KSK:STUDIOS.

art installations

At the Wexner Center for the Arts at the Ohio State University, “Overture” is an example of how motion graphics are becoming an increasing component of fine art installations. Similar to the manner in which title sequence sets the tone of a film, the installation, designed and implemented by Imaginary Forces, served to establish the theme of a much larger exhibit on contemporary architecture and design entitled “Suite Fantastique.” This show spanned “the practices of sculpture, architecture, and film titles,” assuming “the musical metaphor of a symphony.” The installation was devoted to seven of Imaginary Forces’ title sequences to films including Se7en, Donnie Brasco, The Island of Dr. Moreau, and Sphere. Museum visitors were drawn in by a sequential configuration of four elevated, ascending screens that were designed in collaboration with architect Greg Lynn. The images played in concert with the main display, a 17”high-definition screen (4.12).

4.12 “Overture,” from the exhibition “Suite Fantastique.” Wexner Center for the Arts, Ohio State University. Courtesy of imaginary Forces and the Wexner Center for the Arts.

Nir Adar, a NewYork-based chef, food stylist, and artist, was commissioned to create a large-scale video installation for an annual dining design show at the Salone Internazionale del Mobile, a large restaurant in Milan (4.13). At the entrance to the pavilion were two screens (24’ × 7’) that projected images that created a wallpaper of transforming food patterns. Across from the entrance was a 72’ × 7’ wall consisting of five screens that featured photographs of Nir’s food sculptures slowly morphing into each other, in combination with video footage of foods getting squashed between sheets of glass. According to Nir, the footage “had a tension between beauty and repulsion, and had a hypnotic quality to it. When you look at it as mere abstraction, the colors, shapes, and motion are stunningly beautiful, but when you think of the fact that it is foodstuff being squashed, you feel repulsed by it.” Some of images were time-reversed, while others were flipped vertically or horizontally to produce a kaleidoscopic effect. This perfect alchemy of food, fashion, and design resulted in a visual odyssey of form, color, and texture that made the food seem touchable and engaging. Nir further explained: “My idea was to feature and reflect the synergy between food, architecture, design and fashion…I created the pattern’s effect, the food sculptures symbolized architecture, and the food on plates represented the dining.”

4.13 Frames from “Heat As Directed,” a large-scale video installation by Nir Adar. Commissioned by Adam Tihany for his “Dining Design” show at the Salone lnternazionale del Mobile in Milan. Courtesy of KSK Studios and Dyske Suematsu.

educational installations

In recent years, motion graphics have played a significant role in interactive educational installations. For example, multidimensional forms and patterns move and change in size and color on several giant screens in response to people’s traffic patterns in Goldman Sachs’ new Learning Center in NewYork City. Unified Field developed a dynamic media installation that uses an advanced 4D visualization program and Intelligent Recognition Inference System (I.R.I.S.) to simulate the patterns and fluctuations in which twenty-first century market environments, like Goldman Sachs, operate. Data on the history of the stocks in the world’s capital markets is layered with information, such as days of the week and historical events, giving visitors a visceral experience and inviting them to extrapolate their own conclusions on the markets. As a leader in global investment banking, Goldman Sachs wanted to evoke an inspirational learning environment while communicating their commitment to building skills, transforming attitudes, and encouraging new thought and behavioral patterns. This complex installation used Unified Field’s 4D visualization software on an SGI supercomputer and Windows NT server. Four curved, frosted panels and a 42″ plasma screen are mounted on four wing-shaped aluminum poles. Ten feet in front of the panels and embedded in the ceiling is a tracking video camera that monitors the motion of viewers and interfaces with a high-speed image processing board containing gesture recognition software (4.14).

4.14 A dynamic media installation at Goldman Sachs’ Learning Center. Courtesy of Unified Field, Inc.

In the atrium of New Jersey’s Liberty Science Center is an exhibition entitled “Vital Signs,” which features an interactive, streaming media centerpiece that disseminates breaking news about our planet and the museum’s themes of environment, health and invention. A mystical, wraparound display of LED screens is interspersed with projections of 3D forms and interpretive text that move in space to produce a poetic and engaging blend of science, technology, and art. The installation delivers a rich sense of timelessness that inspires observation and inquiry by allowing visitors to select topics, upload information, and view streaming content from all sides of the atrium. Unified Field envisioned this “as a node in a knowledge network, where data from internal and external sources feed multidimensional representations to make the intangible visceral, while powerfully illustrating the everchanging nature of science and technology.” These “sculptural media” elements were designed to function as part of a digital narrowcast network, a digital sign system, a messaging system, and interactive exhibits. Visible from every location in the museum, they effectively alert and inform visitors of the presence and wonder of science (4.15).

4.15 “Vital Signs,” a media installation at the Liberty Science Center. Courtesy of Unified Field, Inc.

retail environments

In retail spaces, immersive environments can create genuine, emotional branding experiences by putting guests into new intuitive and exotic worlds. An example of this is the HBO Shop in HBO’s New York headquarters in Manhattan. A combination of large-scale installation, and motion graphics transform the store into an architectural canvas onto which large-format video projections, choreographed lighting, and audio work together to create a unique visual experience (4.16). The Los Angeles design agency Imaginary Forces collaborated with the architecturaUdesign firm Gensler to transform this 750” retail space into an immersive, animated interior and exterior design that features HBO’s award-winning programming. From the outside, four parallel, large-format video displays appear to recede into an open, deep space from the storefront window to the back, leaving a lasting impression on nearby pedestrians. The store is encased in acid-etched, white glass walls that serve as a projection surface and soak up the changing colors of overhead lights. The LED screens, which appear to be suspended in mid-air, attract the attention of shoppers and entice them into entering the store. Inside the store, they are treated to themed

environments that continually change, as the merchandise plays a secondary, supporting role. Behind the main displays are three high-resolution 65″ plasma screens in portrait mode. In addition to the storefront displays, a 33’-long LED ribbon display is set back into the wall about 1 1/2’ to create an inlet that acts as a backdrop for props from the shows. The continuous animation displayed draws shoppers toward the back of the store. Further, two ceiling-mounted projectors throw 6’-high × 8’-wide video imagery onto facing walls. Lighting was given strong consideration to make the store’s 14’ walls change color. (For example, when the displays feature scenes from The Sopranos, the walls would turn blood red.) Lighting designer Michael Castelli and the design team experimented with various lighting fixtures to see how different types of glass would absorb colored light and chose backpainted glass with an acid-etched surface that allowed for extreme color saturation to emulate the look of a high-resolution monitor.

4.16 As a clever marketing tool, the HBO Shop’s audio, lighting, projection, LED, and plasma displays create multimedia-driven immersive environments for its shoppers.The content it displays is designed to lead shoppers to the store’s checkout area.

It seems likely that, as technology continues to advance, motion graphic designers will have more creative opportunities to play a greater role in designing the content for these types of public spaces.

Animated Exteriors

Today, motion graphics are playing a much greater role in shaping our architectural, urban landscape, due to the rapid advancement of LED technology. Integrated software/hardware systems can stream and scale live video content from various media sources, including servers, DVD players, camcorders, and computers, to accommodate large-scale architectural installations.

Chanel Tokyo is a 10-story building in the Ginza district of the Japanese capitol that was designed in 2004 by Peter Marino Architect, an internationally acclaimed architectural firm based in New York City. Part retail store and part giant electronic billboard, the building’s light metallic edifice is covered with 700,000 computer-controlled LED units that are capable of flashing messages or patterns that adjust to the store’s changing image. Additionally, they can be programmed to emulate a giant swatch of Chanel’s tweed fabric or display video from Chanel’s fashion show. The building’s facade also served as a screen for photographer Michal Rovner’s video installation entitled “Tweed, Tokyo,” which captured the perpetual movements of pedestrians outside the stores from a bird’s-eye view (4.17).

4.17 Chanel Tokyo building in Tokyo, laoan.Artist: Micha, Rovner: a, Phot0grapher:Takashi Orii; Architect: Peter Marino.

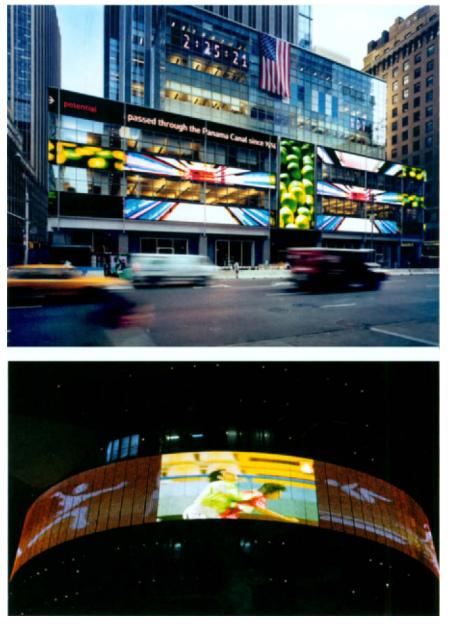

The building at 745 Seventh Avenue, in NewYork City, offers another compelling example of the growing symbiotic relationship between large-scale motion graphics and architecture. Three sides of the building are wrapped with distinctive 7’-high by 133’-long LED display bands, accentuated by a 40’-high video monolith positioned at the building’s west entrance. Advanced engineering, state-of-the-art technology, and innovative, artistic vision makes this building a showpiece for combining aesthetic form with practical function (4.18).

Because conventional, high-resolution video screens are often impractical due to their cost, low-resolution video grid systems are becoming more popular and affordable solutions to large-scale installations and architectural projects. An excellent example of how low-resolution video can be applied to a surface is a massive, 11,700 sq. ft. video screen that wraps around Aspire Tower, the tallest building in Doha, Qatar (4.19). Color Kinetics, a leading innovator in LED lighting, completed the unique, suspended video display that curves with the tower’s architectural design. The facade’s cylindrical screen was constructed from a wire mesh composed of approximately 156,500 nodes of light.

The company’s custom-engineered Chromasic ® microchip allows each node to function as a programmable pixel unit. Live coverage of the Asian Games was fed directly to the nodes through an integrated software/hardware system to project the images. The building’s facade served as a real-time medium for sharing broadcast coverage of the 2006 Asian Games and has provided the public with a dynamic canvas for future video content.

4.18 745 Seventh Ave, NewYork City. Photo courtesy of Daktronics, Inc.

4.19 An intelligent LED lighting system by Color Kinetics forms an I 1,700 sq. ft. video screen that wraps around Aspire Tower in Doha, Qatar. Photo credit: Lumasense. Courtesy of Color Kinetics.

The Yoshikawa Building served as a perfect canvas for Japan’s stunning installation that installed strands containing thousands of controllable, thimble-sized LED nodes behind an exterior glass wall running vertically from the 3rd to the 10th floor (4.20). Color Kinetics’ highly developed control system (Light System Manager) was able to showcase customized light show animations that were built in Adobe Flash. Onlookers were mesmerized by the building’s holiday theme show of light as artistic expression. Animations included swirls of changing colors, geometric shapes, and rushes of color climbing up the facade.

4.20 Yoshikawa Building,Tokyo. Photo credit: Nacasa & Partners. Courtesy of Color Kinetics japan.

The intricate, animated patterns on the tower of Harrah’s Atlantic City Resort & Casino are generated from 4,100’ of anodized aluminum bands of programmable LED lights that wrap around each level of the building. A wide variety of animated effects include color wipes, sunbursts, and large simulations of simple graphic shapes. According to Dave Jonas, president of Harrahs, the lighting effects “have forever changed the skyline of Atlantic City” (4.21).

4.21 An intelligent LED lighting system by Color Kinetics creates a dynamic, animated facade for Harrah’s Atlantic City Resort & Casino. Photo credit: Stone Mountain Lighting Group. Courtesy of Color Kinetics.

Located next to Milan’s famous il Duomo cathedral is La Rinascente, Italy’s largest department store, known for its stylish clothing and world-renowned former employee/designer, Giorgio Armani. Its theme, “Shopping Requires Inspiration,” is expressed through its sophisticated interior design and dazzling window displays. Recently, the building’s facade was transformed to a dazzling series of intricate design effects and patterns of light to create a unique and embracing entrance that would inspire Milan residents and visitors to shop. Cibic & Partners’ exterior lighting scheme used Color Kinetics’ 12,000 flexible LED strands that were installed across two exterior walls of the

building. The nodes were spaced in 12” increments, and each could be individually controlled to generate logos and images. Panels of frosted glass were mounted over the installation to diffuse and magnify the appearance of each node (4.22).

4.22 An intelligent LED lighting system allows individually controllable points of light to form a unique window display for high-end department store La Rinascente in Milan, Italy. Photo credit: Piero Comparotto,Arkilux.

Digital Signage

Digital signage—one of the fastest growing marketing opportunities in the world today—ranges from sports scoreboards to giant video screens in large public spaces such as shopping malls. As a “real-time” messaging medium, it is used to present many forms of content over high-speed networks to video displays in public venues. Interactive digital signage solutions, such as touch-screen kiosks, can deliver dynamic, timely messages that can impart information or influence consumer behavior. In advertising, its marketing content can be crafted based upon specific information that consumers provide or from the purchases that they make. Dynamic digital signage—typically composed of a server, a monitor, and software—is emerging as a new generation of sign technology in the advertising industry. It is capable of delivering dynamic visual content to multiple locations, meaning that advertisers can communicate a brand or message locally or around the world to employees and customers from a central location (4.23).

In response to the demands of advertisers to reach more audiences, and to the decline of prices in LCD, plasma, and projector displays, the need for digital signage has accelerated. Wal-Mart, The Gap, and Foot Locker have already adapted dynamic digital signage technology to promote their brands nationwide. In 2006, a partnership between Latin America’s most dominant companies, Grupo Televisa and Wal-Mart de Mexico (or “Wal-Mex”), launched an in-store media network covering Wal-Mex stores across Mexico. More than 5,000 LCD displays and touchscreen kiosks have enhanced the store’s appeal to shoppers and have assisted them in making purchasing decisions. Shopping malls have also adopted digital signage technology as a strategy to keep consumers informed, entertained, and more likely to buy. The Adspace Mall Network—the largest network of mall-based digital displays in the US.—consists of 8-foot-tall “smart screens” that feature “Today’s Top Ten” specials, events, and commercials. Further, the use of digital signage at airports and museums has also become more extensive.

4.23 Coca-Cola display in Times Square, New York City. Courtesy of Daktronics Inc.

Digital Art Spots (DASs) are a core component of the Business Sponsored Art ProgramTM developed by the company Billijam (4.24). They are original digital artworks that are sponsored by advertisers to support their brand by displaying their logo or tagline, which provides the advertisers with PR buzz and public attention of pedestrians. These artworks can be commissioned for in-store displays, shopping mall displays, digital billboards, digital street networks, or large-scale content (e.g., billboards, wallscapes, spectaculars, street media and transit media). During August through September, 2005, Clear Channel and Billijam partnered to bring DAS to the streets of Manhattan through its digital display network. Businesses could sponsor original artwork to be displayed on eighty LED video screens that were strategically placed at the entrances of major subway stations throughout the city.

4.24 A Digital Art Spot from NewYork City’s Business Sponsored Art ProgramTM. Courtesy of Billijam.

Performance

The integration of motion graphics into live performances, including musical concerts, ceremonies, and awards shows, has increased substantially over the past decade. As staging becomes more extravagant, the prospects of giant illuminated video screens and elaborate lighting facilities call for new methods of choreographing data to synchronize with the changing scenery or music being performed.

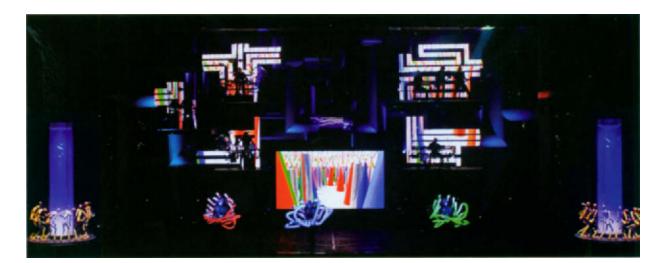

In a performance of Blue Man Group at a custom-designed, 1,800-seat theater at The Venetian Resort Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, Nevada, a matrix consisting of LED displays gave audiences a dynamic, multisensory performance that merged artistic expression with technology.

Accompanying a rectangular video display that hung in the center of the stage were five circuit board displays mounted on different levels of the stage. The performers could access the levels by running up a spiral staircase behind each platform. When lit, they not only convey video content of text and images, but also provide s a light source to backlight the performers with different colors and act as a palette to change the mood of the set (4.25).

4.25 Blue Man Group performance at TheVenetian in Las Vegas, Nevada.Photo courtesy Of Daktronicsi Inc.

Each year, the Blip Festival celebrates the work of international artists who are exploring the musical potential of low-bit technology. element Labs designed a series of fluctuating and abstracted geometric patterns to accompany the rhythmic melodies of “small sounds at large scales pushed to the limit at high volumes” produced by ancient Nintendo and Atari videogame consoles, Game Boys, Sega hardware, and Commodore computers (4.26).

4.26 Blip Festival. Photo courtesy Of Element Labs.

Alternate Spaces

Motion graphics have become an increasing entity in virtual spaces that were made possible by computer technologies during the 1990s. Virtual Reality (VR) technology—which allowed viewers to enter into a dimension that was set apart from their immediate physical space—dissolved the boundary of the frame, allowing designers to break away from familiar compositional devices. The full potential of motion graphics in today’s immersive virtual spaces remains to be realized.

The potential of motion graphics in today’s augmented space (or augmented reality)—physical space that is amplified with electronic and visual information (e.g., static images, typography, animation, and live-action content)— seems even more promising. Many of the scenarios discussed in this chapter, including exhibit designs, museum installations, video wall architecture, and animated interiors and exteriors, are all examples of augmented space.

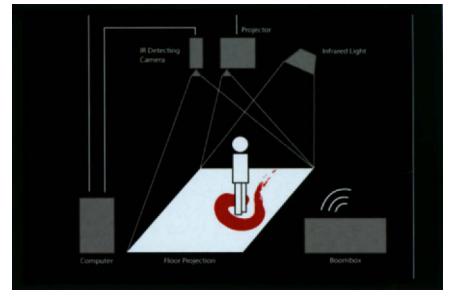

Larger and flatter video displays, 3D technologies, and network technologies are actively entering our immediate, physical world, presenting us with kinetic and context-specific information that can change at any time. Video surveillance technologies, which are becoming ubiquitous, can deliver and extract data (for example, a user’s interests and work patterns) to and from a physical space. AR glasses can layer content over our own visual field. On a much smaller level, “cell space” can hold customizable data that can aid users in checking in at a hotel or in retrieving information about a particular product in a store. Un like virtual reality, which removes the content being presented from real life, augmented reality re-appropriates physical space through media. This enables us to acquire information in much more engaging ways and increase social connections and self-expression in public spaces. For example, RhythmFlow is a collaborative, video-based system that encourages new interpretations of ways of re-adapting to public spaces through body movement. Created by Karl Channell, a digital media and motion graphic designer, this reactive projection system was framed to visualize people’s rhythms in public dance recreation culture. Since dance typically exists in an open space, unconstrained by walls, the design of this system adapts to the idea of “fat free” design, reducing elements down to their essence and focusing on human-centered approaches to problem solving. A video projector is mounted from above and is projected downwards onto a dance circle (4.27). Infrared lights that are projected downward onto the circle are reflected back to an infrared sensitive camera that detects and follows the dancer’s changing shadows. As a result, the history of the dancer’s movements leaves trails of painted pixels behind. Fast movements produce thin lines, while slower ones leave thick blotches remnant of a pen being held to paper. As lines cross paths, they react by changing colors and causing the pixels to become more energized or agitated. As the drawings of older patterns fade away, new patterns are drawn simultaneously. The style of the visuals can be altered, depending on which system the user selects. According to Karl, “The focus remains on the dancers, but with a layer of virtual content and expressiveness on top of them and their surrounding dance territory.”

4.27 RhythmFlow, by Karl Channell.

Summary

The potential of motion graphics in our physical world has been realized and is helping to shape the landscape of environmental design.

New digital technologies are playing a greater role in shaping this visual, public landscape. Video wall systems, which can display very large images without compromising screen resolution, are thriving throughout the world in almost every arena, including trade shows, showrooms, nightclubs, retail stores, restaurants, and sports arenas. New display technologies have used light to transform public spaces, build brands, and invoke imagination by allowing motion graphics to become a physical part of our environment. Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs) have increasingly become the choice of architects and environmental designers who are transforming environments with “intelligent light.” Unlike traditional LCD or plasma displays, LED displays can be built to any size and aspect ratio to allow customized geometric configurations. These displays are visible in front windows, since they are bright enough to compete with sunlight, and can be viewed from distances less than 3 feet.

Motion graphics in interior spaces have become a vital component in setting mood and atmosphere. In corporate lobbies or waiting rooms, for example, they can be used to reinforce a brand, change content to support various messages, and define an ambiance that might be unattainable with other mediums, while maintaining the design integrity of the space. In retail and event spaces, they can add a unique dimension to the space, provide drama in entranceways, and attract outside traffic by presenting the content in display windows. Casinos, restaurants, and hotels have also used motion graphics to stimulate guest interaction and provide unique content as a substitute to mundane television programming.

Immersive environments are designed to blend physical and imaginary worlds in which moving images, text, and audio can respond to humans. The artistic and expressive qualities of motion are appearing more frequently in exhibit designs, retail spaces, and art installations, as well as in complex public environments such as airports and theme parks. Additionally, they are playing a greater role in accommodating large-scale architectural installations and digital signage systems, which are capable of delivering content to multiple locations.

The integration of motion graphics into live performance increased substantially over the past decade. As staging becomes more extravagant, the prospects of giant illuminated video screens and elaborate lighting facilities call for new methods of choreographing data to synchronize with the changing scenery or music being performed.

Although the full potential of motion graphics in today’s immersive virtual spaces remains to be realized, their potential in today’s augmented environments seems even more promising.