1 a brief history of motion graphics

early practices & pioneers

The moving image in Cinema Occupies a Unique niche in the history of twentieth-century art. Experimental film pioneers of the 1920s exerted a tremendous influence on succeeding generations of animators and graphic designers. In the motion picture film industry, the development of animated film titles in the 1950s established a new form of graphic design called motion graphics.

—Cecile Starr

Precursors of Animation

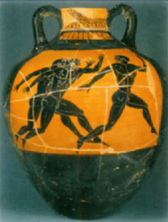

Since the beginning of our existence, we have endeavored to achieve a sense of motion in art. Our quest for telling stories through the use of moving images dates back to cave paintings found in Lascaux, France and Altamira, Spain, which depicted animals with multiple legs to suggest movement. Attempts to imply motion were also evident in early Egyptian wall decoration and Greek vessel painting.

1.1 Panathenaic amphora, c. 500 BC. Photo by H. Lewandowski, Louvre, Paris, France. Réuníon des Musées Nationaux © Art Resource, NY.

persistence of vision

Animation cannot be achieved without understanding a fundamental principle of the human eye: persistence of vision. This phenomenon involves our eye’s ability to retain an image for a fraction of a second after it disappears. Our brain is tricked into perceiving a rapid succession of different still images as a continuous picture. The brief period during which each image persists upon the retina allows it to blend smoothly with the subsequent image.

early optical inventions

Although the concept of persistence of vision had been firmly established by the nineteenth century, the illusion of motion was not achieved until optical devices emerged throughout Europe to provide animated entertainment. Illusionistic theatre boxes, for example, became a popular parlor game in France. They contained a variety of effects that allowed elements to be moved across the stage or lit from behind to create the illusion of depth. Another early form of popular entertainment was the magic lantern, a device that scientists began experimenting with in the 1600s (1.2). Magic lantern slide shows involved the projection of hand-painted or photographic glass slides. Using fire (and later gas light), magic lanterns often contained built-in mechanical levers, gears, belts, and pulleys that allowed the slides (which sometimes measured over a foot long) to be moved within the projector. Slides containing images that demonstrated progressive motion could be projected in rapid sequence to create complex moving displays.

One of the first successful devices for creating the illusion of motion was the thaumatrope, made popular in Europe during the 1820s by London physicist Dr. John A. Paris. (Its actual invention has often been credited to the astronomer Sir John Herschel.) This simple apparatus was a small paper disc that was attached to two pieces of string and held on opposite sides (1.3). Each side of the disc contained an image,

1.2 Magic lantern slide & projectors. Photos by Dick Waghorne. Courtesy of the Wileman Collection of Optical Toys.

and the two images appeared to become merged together when the disc was spun rapidly. This was accomplished by twirling the disc to wind the string and gently stretching the strings in opposite directions. As a result, the disc would rotate in one direction and then in the other. The faster the rotation, the more believable the illusion.

In 1832, a Belgian physicist named Joseph Plateau introduced the phenakistoscope to Europe. (During the same year, Simon von Stampfer of Vienna, Austria invented a similar device called the stroboscope.) This mechanism consisted of two circular discs mounted on the same axis to a spindle. The outer disc contained vertical slots around the circumference, and the inner disc contained drawings that depicted successive stages of movement. Both discs spun together in the same direction, and when held up to a mirror and peered at through the slots, the progression of images on the second disc appeared to move. Plateau derived his inspiration from Michael Faraday, who invented a device called “Michael Faraday’s Wheel,” and Peter Mark Roget, the compiler of Roget’s Thesaurus. The phenakistoscope was in wide circulation in Europe and America during the nineteenth century until William George Homer invented the zoetrope, which did not require a viewing mirror. Referred to as the “wheel of life,” the zoetrope was a short cylinder with an open top that rotated on a central axis. Long slots were cut at equal distances into the outer sides of the drum, and a sequence of drawings on strips of paper were placed around the inside, directly below the slots. When the cylinder was spun, viewers gazed through the slots at the images on the opposite wall of the cylinder, which appeared to spring to life in an endless loop (1.4).

1.3 Thaumatrope discs and case. Photo by Dick Waghorne. Courtesy of the Wileman Collection of Optical Toys.

1.4 Zoetrope, top view. Photo: Dick Waghorne. Wileman Collection of Optical Toys.

The popularity of the zoetrope declined when Parisian engineer Emile Reynaud invented the praxinoscope. A precursor of the film projector, it offered a clearer image by overcoming picture distortion by placing images around the inner walls of an exterior cylinder. Each image was reflected by a set of mirrors attached to the outer walls of an interior cylinder (1.5). When the outer cylinder is rotated, the illusion of movement is seen on any one of the mirrored surfaces. Two years later, Reynaud developed the praxinoscope theatre, a large wooden box containing the praxinoscope. The viewer peered through a small hole in the box’s lid at a theatrical background scene that created a narrative context for the moving imagery.

1.5 Praxinoscope. Photos by Dick Waghorne. Wileman Collection of Optical Toys.

Earlv Cinemtic Inventim

During the late 1860s, former California governor Leland Stanford became interested in the research of Etienne Marey, a French physiologist who suggested that the movements of horses were different from what most people thought. Determined to investigate Marey’s claim, Stanford hired Eadward Muybridge, who earned a reputation for his photographs of the American West, to record the moving gait of his racehorse with a sequence of still cameras (1.6). Muybridge continued to conduct motion experiments, some of which were published in an 1878 article in Scientific American. This article suggested that its readers cut the pictures out and place them in a zoetrope to recreate the illusion of motion. This fueled Muybridge to invent the zoopraxiscope, an instrument that allowed him to project up to 200 single images on a screen. This forerunner of the motion picture was received with great enthusiasm in America and England. In 1884, Muybridge was commissioned by the University of Pennsylvania to further his study of animal and human locomotion and produced an enormous compilation of over 100,000 detailed studies of animals and humans engaging in various physical activities. These volumes were a great aid to visual artists in helping them understand movement.

In 1889, Hannibal W. Goodwin, an American clergyman, developed a transparent, celluloid film base, which George Eastman began manufacturing. For the first time in history, long sequences of images could be contained on a single reel. (Zoetrope and praxinoscope strips were limited in that they could only display approximately 15 images per strip.) In Britain, Louis and Auguste Lumiere developed the kinora, a home movie device that consisted of a 14-cm wheel that held a series of pictures. When the wheel was rotated by a handle, the rapid succession of pictures in front of a lens gave the illusion of motion(1.7). By 1894, coin-operated kinetoscope parlors could be seen in New York

1.6 Motion study, by Eadweard Muybridge. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

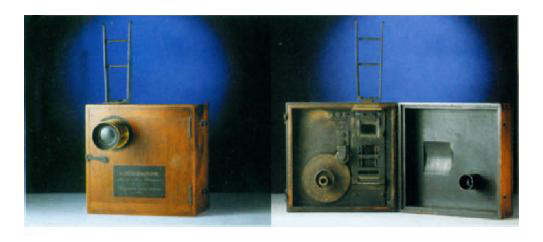

City, London, and Paris. This eventually led to their invention of the Cinematographe, the first mass-produced camera-printer-projector of modern cinema (1.8). For the first time in history, cinematographic films were projected onto a large screen for a paying public.

1.7 Kinara. Photo by Dick Waghorne. Wileman Collection of Optical Toys

In addition to filming movies, new developments led to the concept of creating drawings that were specifically designed to move on the big screen. Prior to Warner Brothers, MGM, and Disney, the origins of classical animation can be traced back to newspapers and magazines that displayed political caricatures and comic strips. One of the most famous cartoon personalities before Mickey Mouse was Felix the Cat. Created by Australian cartoonist Pat Sullivan and animated by Otto Mesmer, Felix was the first animated character to have an identifiable screen personality. In 1914, an American newspaper cartoonist named Winsor McCay introduced a new animated character to the big screen—Gertie the Dinosaur. The idea of developing a likeable personality from a living creature had a galvanizing impact upon audiences. As the film was projected on screen, McCay would stand nearby and interact with his character.

1.8 The Cinematographe, the first mass-produced camera-printerprojector of modern cinema. Courtesy: National Museum of American History.

The cell animation process, developed in 1910 by Earl Hurd at John Bray studios, was a major technical breakthrough in figurative animation that involved the use of translucent sheets of celluloid for overlaying images. Early artists who utilized Bray’s process included Max Fleischer (Betty Boop), Paul Terry (Terrytoons), and Walter Lantz (Woody Woodpecker). Stop-motion animation, which can be traced back to the invention of stop-action photography, was used by French filmmaker Georges Méliès, a Paris magician. In Méliès’ classic film, A Trip to the Moon (1902), stop-action photography allowed Méliès to apply his techniques, which were derived from magic and the theatre, to film. Additional effects, such as the use of superimposed images, double exposures, dissolves, and fades, allowed a series of magical transformations to take place.

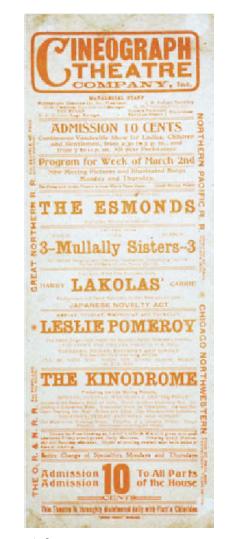

1.9 Ad for “Cineograph Theatre” showing a daily program of motion picture shows (I 1899–1900). Courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

Four years later, J. Stuart Blackton, an Englishman who immigrated to the United States, discovered that by exposing one frame of film at a time, a subject could be manipulated between exposures to produce the illusion of motion. In 1906, his company, Vitagraph, released an animated short titled Humorous Phases of Funny Faces, one of the earliest surviving American animated films. Blackton’s hand is seen creating a line drawing of a male and female character with chalk on a blackboard. The animation of each face’s changing facial expression was accomplished through single-frame exposures of each slight varia-tion. When the artist’s hand exits the frame, the faces roll their eyes and smoke issues from a cigar in the man’s mouth. At the end of the film, Blackton’s hand reappears to erase the figures. This new stop-motion technique shocked audiences as the drawings magically came to life (Chapter 10, figure 10.7).

1.10 Postage stamp with portrait of Georges Melies. Courtesy of Anthology Film Archives.

Emile Cohl and Max Fleischer expanded the resources of animation by mixing live footage with hand-drawn elements. Known as the father of French animation, Emile Cohl, a newspaper cartoonist, is known for his first classic film, Fantasmagorie (1908). Cohl’s 300 subsequent short animations were a product of the Absurdist school of art, which derived artistic inspiration from drug-induced fantasy, hallucinations, and insanity. These works combined hand-drawn animated content and live action. Around 1917, Max Fleischer, an admirer of McCay’`s realistic style, patented the technique of rotoscoping. This process involved drawing frames by tracing over previously filmed live-action footage, allowing the animator to produce smooth, lifelike movements. Fleischer’s next invention, the Rotograph, enabled animated characters to be placed into live, realistic settings. A live action background would be filmed and projected one frame at a time onto a piece of glass. A cel containing an animated character would be placed on the front side of the glass, and the composite scene would be filmed. With this technique, Fleischer went on to develop the personalities of famous characters such as Koko the Clown, Betty Boop, Popeye, and Superman.

Experimental Animation

At the turn of the twentieth century, postwar technological and indus trial advances, and changing social, economic, and cultural conditions of monopoly capitalism throughout Europe fueled artists’ attempts to reject classical representation. This impulse led to the rapid evolution of abstraction in painting and sculpture. Revolutionary Cubist painters began expressing space in geometric terms. Italian Futurists became interested in depicting motion on the canvas as a means of liberating the masses from the cruel treatment that they were receiving from the government. Dada and Surrealist artists sought to overthrow traditional constraints by exploring the spontaneous, the subconscious, and the irrational. These forms of Modernism abandoned the laws of beauty and social organization in an attempt to demolish current aesthetic standards of art. This was manifested in music, poetry, sculpture, painting, graphic design, and experimental filmmaking.

pioneers of “pure cinema”

During the 1920s, huge movie palaces, fan magazines, and studio publicity departments projected wholesome images of stars. (Few people knew the names of the directors!) Hollywood’s mass-produced romances and genre films reaffirmed values such as the family and patriotism. In Germany, France, and Denmark, filmmakers began to embrace a more personal attitude toward film through the medium of animation. Their basic motivation was not inspired by commercial gain; rather, it came from a personal drive to create art. “Pure cinema,” as the first abstract animated films were called, won the respect of the art community who viewed film as an expressive medium.

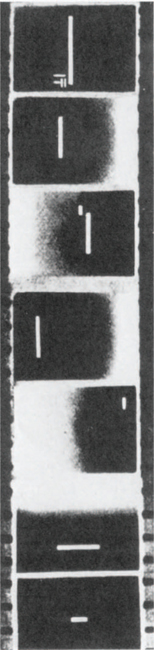

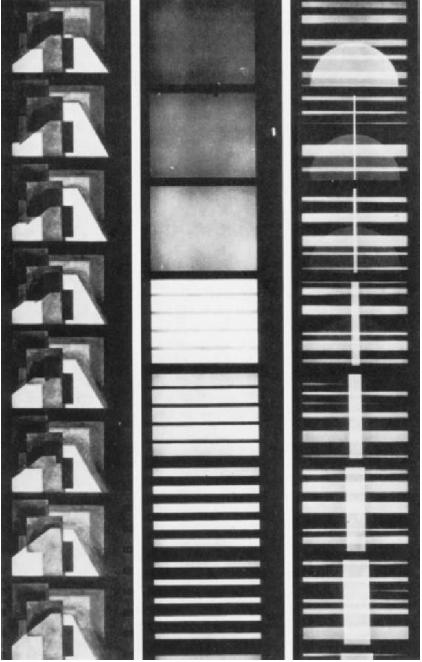

During the early 1900s, Swedish musician and painter Viking Eggeling described his theory of painting by way of music, in terms of “instruments” and “orchestration.” His desire was to establish what he referred to as a “universal language” of abstract symbols, and he strived to accomplish this by emphasizing musical structure and avoiding representation. The nihilistic tendencies of the Dada movement gave Eggeling the freedom to break from conventional schools of thought, and he collaborated with German filmmaker Hans Richter on a series of scroll drawings that utilized straight lines and curves of varying orientations and thicknesses. These structures were arranged in a linear progression across a long scroll of paper, forcing viewers to see them in a temporal context. Driven by the need to integrate time into his work, he turned his attention to film and produced Symphonie Diagonale in 1923. Taking almost four years to complete, this frameby-frame animation showed a strong correlation between music and painting in the movements of the figures, which were created from paper cutouts and tin foil (1.11). Eggeling died in Berlin approximately two weeks after his film was released.

1.11 Filmstrip from the work Of Viking Eggeling. From Experimental Animation, courtesy of Cecile Starr

A major contributor to the Cubist movement, Fernand Léger has been described as “a painter who linked industry to art.” Born in northwestern France, he desired to express his love for city life, common people, and everyday objects in painting. By 1911, he became identified with his tubular and curvilinear structures, which contrasted with the more angular shapes produced by other cubists, such as Picasso and Braque. During the 1920s, Leger began to pursue film and produced his classic, Ballet Mechanique (1923). Created without a script, this masterpiece demonstrated a desire to combine the energy of the machine with the elegance of classical ballet. Fragments of reflective, metal machinery, disembodied parts of figures, and camera reflections were orchestrated into a seductive, rhythmic mechanical dance. Conceptually, this film has been interpreted as a personal statement in a world of accelerating technological advancement and sexual liberation. From an artistic perspective, it represented a daring jump into the territory of kinetic abstraction.

German Dadaist Hans Richter collaborated with Viking Eggeling to produce a large body of “scroll drawings” that depicted sequential transformations of geometric forms that he described as “the music of the orchestrated form.” Richter saw film animation as the next logical step for expressing the kinetic interplay between positive and negative forms. Richter’s silent films of the late 1920s demonstrated a more surreal approach that combined animation with live-action footage. At the time, these shocking films challenged artistic conventions by exploring fantasy through the use of special effects, many of which are used in contemporary filmmaking. In Ghosts Before Breakfast (1927), people and objects engage in unusual behavior set in bizarre and often disturbing settings. Flying hats continually reappear in conjunction with surrealistic live images of men’s beards magically appearing and disappearing, teacups filling up by themselves, men disappearing behind street signs, and objects moving in reverse. In a scene containing a bull’s eye, a man’s head becomes detached from his body and floats inside the target. In another scene of a blossoming tree branch, fast-motion photography was used. Richter also played back the film in reverse and used negatives to defy the laws of the natural world.

1.12 Filmstrip from Rhythm 23 (1923) by Hans Richter. From Experimental Animation, courtesy of Cecile Starr.

After World War I, German painter Walter Ruttmann became impatient with the static quality of his artwork and saw the potential of film as a medium for abstraction, motion, and the passage of time. In 1920, he founded his own film company in Munich and pioneered a series of playful animated films entitled Opus, all of which explored the interaction of geometric forms (1.13). (Opus 1 [1919-1921] was one of the earliest abstract films produced and one of the few that was filmed in black and white and hand-tinted.) The technical process that Ruttmann employed remains questionable, although it is known that he painted directly onto glass and used clay forms molded on sticks that, when turned, changed their appearance. Ruttmann’s later documentary, Berlin: Symphony of a City, gives a cross-section impression of life in Berlin in the late 1920s. The dynamism of urbanization in motion is portrayed in bustling trains, horses, masses of people, spinning wheels, and machines, offering an intimate model of Berlin.

1.13 Frames from Opus III (c. 1923) and Opus IV (c. 1924), by Walter Ruttmann. From Experimental Animation, courtesy of Cecile Starr.

Born in Brooklyn, New York, Emanuel Radnitsky (known as Man Ray), became an enigmatic leader of the Dada—Surrealist and American avant-garde movements of the 1920s and 1930s. After establishing Dadaism in New York City with Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia, he moved to Paris and became a portrait photographer for the wealthy avant-garde. By the early 1920s, he developed a reputation for his use of natural light and informal poses during a time when Pictorialism was the predominant style of photog-raphy in Europe. Commercial success gave him the freedom to experiment, and his discovery of the “Rayograph” (later called the photogram) made a significant contribution to the field of photography. Throughout the 1920s, Man Ray produced Surrealist films that were created without a camera, such as Anemic Cinema (1925–26) and L’Etoile de Mer (1928). He often described them as “inventions of light forms and movements.”

In the 1930s, Russian-born filmmaker Alexander Alexeieff and American Claire Parker invented the pinboard (later named the pinscreen), one of the most eccentric traditional animation techniques. This contraption consisted of thousands of closely-spaced pins that were pushed and pulled into a perforated screen, using rollers to achieve varying heights. When subject to lighting, cast shadows from the pins produced a wide range of tones, creating dramatic textural effects that resembled a mezzotint, wood carving, or etching. The extraordinary results of this process are evident in classic pieces such as Night on Bald Mountain (Chapter 6, figure 6.35) and The Nose, a film based on a story about a Russian major whose nose is discovered by a barber in a loaf of bread. According to Parker, “Instead of brushes we use different sized rollers; for instance, bed casters, ball-bearings, etc., to push the pins toward either surface, thus obtaining the shades or lines of gray, black, or white, which we need to compose the picture.”

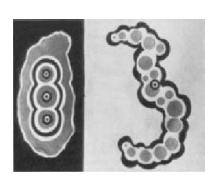

Revolutionary New Zealand animator Len Lye, who often referred to himself as “an artist for the twenty-first century,” pioneered the directon-film technique of cameraless animation by painting and scratching onto 35mm celluloid. His use of abstract, metaphorical images are a product of his association with Surrealism, Futurism, Constructivism, and Abstract Expressionism, as well as his affinity for jazz, Oceanic art, and calligraphy. His use of percussive music, saturated color, and organic forms had a major impact on a genre that later became known as music video. Living in Samoa between 1922 and 1923, Lye became inspired by Aboriginal motifs and produced his first animated silent film, Tusalava (1929), which he created to express “the beginnings of organic life” (1.14). This film took approximately two years to complete, since each frame was hand-painted and photographed individually. In a 16mm abstract film titled Free Radicals (1958), Lye scratched the content onto a few thousand feet of black film leader using tools ranging from sewing needles to Indian arrowheads.

1.14 Frame from Tulsava (1929), by Len Lye. From Experimental Animation, courtesy of Cecile Starr.

In Canada, Norman McLaren has been described as a “poet of animation.” Inspired by the masterpieces of filmmakers Eisenstein and Pudovkin, he began animating directly onto film, scratching into its emulsion to make its stock transparent. (At the time, he was unaware that Len Lye was conducting similar experiments.) In 1941, he was invited to join the newly formed National Film Board of Canada (NFB), and there, he founded an animation department and experimented with a wide range of techniques. Films, such as Fiddle-de-Dee (1947) and Begone Dull Care (1949), were made by painting on both sides of 35mm celluloid. Incredibly rich textures and patterns were achieved through brushing and spraying, scratching, and pressing cloths into the paint before it dried. For over four decades, McLaren produced films for the NFB that served as an inspiration for animators through out the world. In 1989, two years after his death, the head office building of the NFB was renamed the Norman McLaren Building.

Berlin animator Lotte Reiniger is known for her silhouette cut-out animation style during the sound-on film era of the 1930s. Her full-length feature film, The Adventures of Prince Achmed (Chapter 10, figure 10.12), was among the first animated motion pictures to be produced, taking approximately three years to complete. The main characters were marionettes that were composed of black cardboard figures cut out with scissors and photographed frame-by-frame.

1.15 Lotte Reiniger in the 1920s. From Experimental Animation, courtesy of Cecile Starr.

1.16 Mary Ellen Bute, c. 1954. From Experimental Animation, courtesy of Cecile Starr.

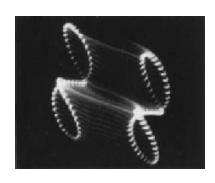

Born in Texas, Mary Ellen Bute studied painting and earned a degree in stage lighting at Yale. She became interested in filmmaking as a means of exploring kinetic art, and in collaboration with Joseph Schillinger, a musician and musical composer who had developed a theory about the reduction of musical structure to mathematical formulas, began animating a film that would prove that music could be illustrated with images. Because of the intricacy of the images, however, this ambitious film was not completed. Mary Ellen Bute incorporated many different types of found objects in her work including combs, colanders, Ping-Pong balls, and eggbeaters and photographed them frame-by-frame at various speeds. She intentionally distorted them by filming their reflections against a wall to conceal their origin. Her first film from the 1930s, Rhythm in Light, involved shooting paper and cardboard models through mirrors and glass ashtrays to achieve multiple reflec-tions. Mary Ellen also explored oscilloscope patterns as a means of controlling light to produce rhythm (1.17). Between 1934 and 1959, her abstract films played in regular movie theaters around the country.

As a leading innovator of experimental film, Oskar Fischinger believed that visual music was the future of art. Born in Germany, he was exiled to Los Angeles when Hitler came to power and the Nazis censured abstraction as “degenerate.” During the early 1920s, his pursuit of the Futurist goal to make painting dynamic manifested in a series of film studies created from charcoal drawings of pure, geometric shapes and lines. Constructed from approximately 5,000 drawings, they demonstrated a desire to marry sound and image. Fischinger also experimented with images produced from a wax-slicing machine and explored color film techniques, cardboard cutouts, liquids, and structural wire supports. In 1938, Fischinger was hired by Disney Studios to design and animate portions of Fantasia. His presence in Hollywood helped shape generations of West Coast artists, filmmakers, graphic designers, and musicians.

1.17 Frame from Abstronic (1954), by Mary Ellen Bute. From Experimental Animation, courtesy of Cecile Starr.

Born in Portland, Oregon, Harry Smith, who began recording Native American songs and rituals as a teenager, emerged as a complex artistic figure in sound recording, filmmaking, painting, and ethnographic

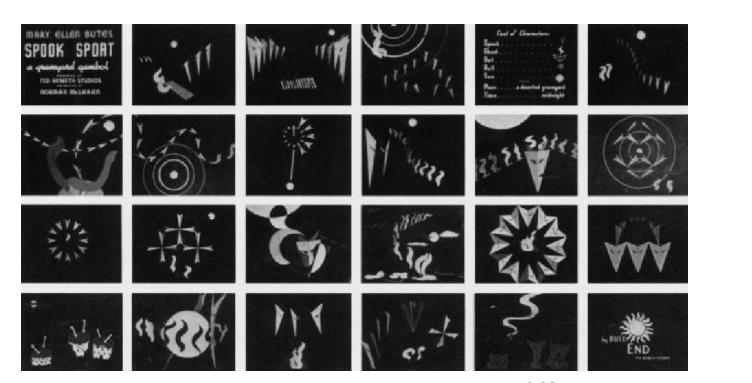

1.18 Frames from Spook Sport (1939), by Mary Ellen Bute and Norman McLaren. From Experimental Animation, courtesy of Cecile Starr.

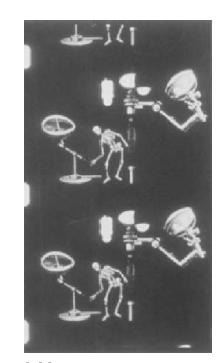

collecting. Intrigued by the occult, he often spoke of his art in alchemical and cosmological terms. His process involved hand-painting onto 35mm film stock in combination with stop motion and collage. Similar to his life and personality, his compositions are complex and mysterious and have been interpreted as explorations of unconscious mental processes. Like an alchemist, he worked on his films secretly for almost 30 years. At times, Smith spoke of synesthesia and the search for correspondences among color, sound, and movement. His painstaking direct-on-film process involved a wide range of nonconventional tools and techniques ranging from adhesive gum dots to Vaseline, masking tape, and razor blades. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Smith’s collage films became increasingly complex. He cut out pictures and meticulously filed them away in envelopes, building up an image archive which he used in later works such as Film # 12, Heaven and Earth Magic (1.20).

After studying painting at Stanford, Robert Breer moved to Paris and became heavily influenced by the hard-edged geometric qualities of Neo-plasticism and the abstractions of the De Stijl and Blue Rider movements. Eventually, Breer felt restricted by the boundaries of the static canvas and produced a series of animations that attempted to preserve the formal aspects of his paintings. He also experimented with rapid montage by juxtaposing frames of images in quick succession.

1.19 Painting (untitled) by Harry Smith. Courtesy of the Harry Smith Archives and Anthology Film Archives.

1.20 Frame from Film # 12, Heaven and Earth Magic (1957–1962), by Harry Smith. Courtesy of the Harry Smith Archives and Anthology Film Archives.

Jan Švankmajer was one of the most remarkable European filmmakers of the 1960s. His innovative works have helped expand traditional animation beyond the concept of Disney cartoons. His bizarre, often grotesque, Surrealist style aroused controversy after the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, and his opportunities to work in Czech studios were restricted. Nevertheless, he employed a wide range of techniques and used almost anything he could find, including man-made objects, animals, plants, insects, and bones in order to fuse object animation with live action. Švankmajer’s love of rapid montage and extreme close-ups is evident in films such as Historia Naturae (1967), Leonardo’s Diary (1972), and Quiet Week In A House (1969). His surrealist orienta-tion is evident in his use of somber, haunting images of living creatures and inanimate objects that are thrust into worlds of ambiguity. The impact of his images often dominates over the narrative, as people take on the appearance of robots, and inanimate objects engage in savage acts of decapitation, suicide, and cannibalism. In The Last Trick of Mr. Schwarcewalld and Mr. Edgar (1964), a beetle crawls out of the head of the main character who wears a wooden mask. In Jabberwocky (1971), branches blossom and apples drop and burst open to reveal maggots. A jackknife dances on a table, falls flat, and its blade closes to produce a trickle of blood that oozes out of its body. In another scene, a tea party of dolls dine at a small table, consuming other dolls who have been crushed in a meat grinder and cooked on a miniature range.

“By simply limiting the viewer of a painting to 144th of a second I produce one unit of cinema and by adding several of these units together I produce a motion picture.”

— Robert Breer

Inspired by Eastern European culture and the films of Jan Švankmajer, identical twin brothers Stephen and Timothy Quay (the “Brothers Quay”) were among the most accomplished puppet animation artists to emerge during the 1970s. Their exquisite sense of detail and decor, openness to spontaneity, and use of extreme close-ups have enchanted audiences worldwide, and their innovations contributed a unique sense of visual poetry to animated film. The miniature sets of the Quays create a world of repressed childhood dreams. Absurd and incomprehensible images (e.g., antiquated-looking toys, machinery, bones, meat, etc.) exist in a chaotic, multilayered world where human characters live at the mercy of insidious machines. Unexpected, irrational events distort space and time beyond recognition. The harsh, grimy atmosphere of decay, the ominous quality of chiaroscuro, the dazzling use of light and texture and adept camera movement give their films an eerie, sublime quality. Some of their best known shorts include Street of Crocodiles (1986), The Institute Benjamenta (1995), and In Absentia (2000). The Quays have also produced network IDs, commercials for Coca-Cola, MTV, and Nikon, and music videos including Peter Gabriel’s “Sledgehammer.” The Brothers Quay currently reside in North London and work in South London at their studio, Atelier Koninck.

“We really believe that with animation one can create an alternate universe, and what we want to achieve with our films is an ‘objective’ alternate universe, not a dream or a nightmare but an autonomous and self-sufficient world, with its particular laws and lucidity… The same type of logic is found in the ballet, where there is no dialogue and everything is based on the language of gestures, the music, the lighting, and sound. ”

— Stephen & Timothy Quay

During the 1970s, American animators Frank and Caroline Mouris developed the technique of collage animation in their Academy Award-winning film Frank Film (1973). In the 1990s, they went onto create the short, Frankly Caroline (1999). Both films are characterized by an overabundance of images representing Western culture and iconography. The objective of these films was to provide a visual biography of their lives and their collaborative personal and working partnership. Frank Mouris describes Frank Film as a “personal film that you do to get the artistic inclinations out of your system before going commercial.” The Mouris’ animation style has appeared in many music videos and television spots on PBS, MTV, and the Nickelodeon channels. Their animated shorts have also been featured on programs such as Sesame Street and 3-2-1 Contact.

computer animation pioneers

Since the 1960% advancements in digital technology have exerted a tremendous influence over subsequent generations of animators and commercial motion graphic designers all over the world.

John Whitney hypothesized a future in which computers would be reduced to the size of a television for home use. His interest in film, electronic music, and photography was influenced by French and German avant-garde filmmakers of the 1920s. Whitney felt that music was part of the essence of life and attempted to balance science with aesthetics by elevating the status of the computer as a viable artistic medium to achieve a correlation between musical composition and abstract animation. In collaboration with his brother James, he devised a pendulum sound recorder that produced synthetic music for his animated compositions. During World War II, Whitney discovered that the targeting elements in bomb sights and antiaircraft guns could calculate trajectories that could be used to plot graphics. From surplus antiaircraft hardware, he built a mechanical analog computer (which he called a “cam machine”) that was capable of metamorphosing images and type. This later proved to be successful in commercial advertising and in film titling. During the 1950s, Whitney began producing 16mm films for television and produced the title sequence for Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (created in partnership with Saul Bass). He also directed short musical films for CBS and in 1957, worked with Charles Eames to create a large seven-screen presentation for the Fuller Dome in Moscow. In 1960, Whitney founded Motion Graphics Inc. and produced openings for shows such as Dinah Shore and Bob Hope. He also produced Catalogue, a compilation of the effects that he had perfected with his analog computer (1.23). In 1974, John Whitney, Jr. and Gary Demos formed a Motion Picture Products group which led to the first use of computer graphics for motion pictures while working on the film Westworld (1973). This film employed pixelization—a technique that produces a computerized mosaic by dividing a picture into square blocks and averaging each block’s color into a single color.

1.21 Frames from Arabesque, by John Whitney. Courtesy of The Estate of John and James Whitney and the iota Center. All rights reserved.

1.22 PJohn Whitney’s book, Digital Harmony: On the Complementarity of Music and Visual Art, explains the influence of historical figures such as Pythagoras and Arnold Schoenberg on his artistic process. It also provides insight into his groundbreaking work in computer animation and the integration of music and filmmaking. Courtesy of The Estate of John and James Whitney. All rights reserved.

1.23 Frame from Catalogue, by John Whitney. Courtesy of The Estate of John and James Whitney and the iota Center. All rights reserved.

During the 1960s, Stan Vanderbeek became one of the most highly acclaimed underground filmmakers to experiment with computer graphics and multiple screen projection. He produced films using a variety of processes including collage, hand-drawn animation, live action, film loops, video, and computer-generated graphics. He also invented the Movie-Drome theatre, a 360° overhead projection area that surrounded audiences with images as they lay on their backs around the perimeter of the dome. This development later influenced the construction of worldwide “life theaters” and image libraries to advance international communication and global understanding.

1.24 John Whitney. Photo courtesy of Anthology Film Archives.

During the time that Vanderbeek was producing collage films, Ken Knowlton, an employee of Bell Labs, was developing a Beflix programming language for the production of raster-based animation, a system used by Vanderbeek. Knowlton also investigated pattern perception and developed an algorithm that could fragment and reconstruct a picture using dot patterns. During the 1990s, he won several awards for his digital mosaics that, close up, depicted a complex array of objects, and from a distance, became discernible as a recognizable image.

In 1961, MIT student Ivan Sutherland created a vector-based drawing program called Sketchpad. Using a light pen with a small photoelec-tric cell in its tip, shapes could be constructed without having to be drawn freehand. He also invented the first head-mounted display for viewing images in stereoscopic 3D. (Twenty years later, NASA used his technique to conduct virtual reality research.) Dave Evans, who was hired to form a computer science program at the University of Utah, recruited Sutherland, and by the late 1960s, the University of Utah became a primary computer graphics research facility that attracted John Warnock (founder of Adobe Systems and inventor of the PostScript page description language) and Jim Clark (founder of Silicon Graphics).

A few years earlier, Robert Abel, who had originally produced films with Saul Bass, established the computer graphics studio Robert Abel & Associates with his friend Con Pederson in 1971. He was contracted by Disney to develop promotional materials and the opening sequence to The Black Hole (1979), and later to produce graphics for Disney’s movie Tron (1982). Abel won multiple awards, including two Emmys and a Golden Globe, and his company became recognized for its ability to incorporate conventional cinematography and special effects techniques into the domain of CGI

Motion Graphics in Film Titles

Film title design evolved as a form of experimental filmmaking within the realm of commercial motion pictures. The origin of film titles can be traced back to the silent film era, where credit sequences were presented on title cards containing text. They were inserted throughout the film to maintain the flow of the story. (Ironically, they often interfered with the pacing of the narrative.) Hand-drawn white lettering superimposed over a black background provided information such as the title, the names of the individuals involved (director, technicians, cast, etc.), the dialogue, and action for the scenes. Sometimes the letters were embellished with decorative outlines, and usually the genre of the film dictated the style. For example, large, distressed block letters marked horror, while a fine, elegant script characterized romance. After the implementation of sound, titles began to evolve into complete narratives and became elevated to an art form.

1.25 Saul Bass in his later years. Photo courtesy of Anthology Film Archives.

During the 1950s, American graphic design pioneer Saul Bass became the movie industry’s leading film title innovator. His evocative opening credit sequences for directors such as Alfred Hitchcock, Martin Scorsese, Stanley Kubrick, and Otto Preminger garnered public attention and were considered to be miniature films in themselves.

Born in New York City in 1920, Bass developed a passion for art at a young age and became grounded in the aesthetics of Modernist design through the influence of Gyorgy Kepes, a strong force in the establishment of the Bauhaus in Chicago. After working for several advertising agencies, he moved to Los Angeles and founded Saul Bass & Associates in 1946. His initial work in Hollywood consisted of print for movie advertisements and poster designs. In 1954, he created his first title sequence for the film Carmen Jones (1954). Bass viewed the credits as a logical extension of the film and as an opportunity to enhance the story. His subsequent animated openings for Otto Preminger’s The Man With the Golden Arm (1955) and Anatomy of a Murder (1959) elevated the role of the movie title as a prelude to the film. They also represented a rebirth of abstract animation since the experimental avant-garde films from the 1920s. According to Director Martin Scorsese, “Bass fashioned title sequences into an art, creating in some cases, like Vertigo, a mini-film within a film. His motion graphics compositions function as a prologue to the movie—setting the tone, providing the mood and foreshadowing the action.”

During the 1960s, Friz Freleng, known for his work on the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies series of cartoons from Warner Bros, developed the opening cartoon animation for The Pink Panther (1963). This immediately became an icon of pop culture, appearing in a number of sequels and eventually its own television series. Freleng’s cool, contemporary design style, the use of spinning letters and unscrambling words, along with the distinctive theme music from Henry Mancini was a complete departure from the cheaply made theatrical cartoons of the time.

In contrast, American designer Maurice Binder’s openings for the classic James Bond movies gained popularity in their abstract, erotic imagery. Beginning with Dr. No and ending with License to Kill, Binder’s stylish credit sequences for fourteen 007 films became a trademark of the series and have been described as a visual “striptease” of nude figures against swirling, enveloping backgrounds of color. In a time where pop music and fashion permeated mainstream entertainment, these sensual openings were a perfect match for Bond’s character. The classic gun barrel opening that precedes the traditional pre-credit opening sequences in every 007 film was initially created by Binder for the opening to Dr. No (1962). Gunshots, which are fired across the screen, transform into the barrel of a gun that follows the motion of the silhouetted figure of Bond. The figure turns toward the camera and fires, and a red wash flows down from the top of the screen as the gun barrel becomes reduced to a white dot. Binder achieved this effect by actually photographing through the barrel of a .38 revolver. This sequence became a trademark of the 007 series and was used extensively throughout its promotion. (Each actor playing Bond had his own interpretation of the famous gun barrel walk-on, the first being stuntman Bob Simmons, then Sean Connery, George Lazenby, Roger Moore, Timothy Dalton, and finally Pierce Brosnan.)

Terry Gilliam’s contribution to animation is manifested in a series of bizarre title sequences and animated shorts that he produced for Monty Python. Born in Minnesota, Gilliam became strongly influenced by Help! and MAD Magazine while studying at Occidental College in California. Gilliam joined Fang, the college’s literary magazine, and sent copies of the magazine to Harvey Kurtzman, editor of Help! and co-founder of MAD. After receiving a positive response from Kurtzman, he went to New York and was hired as Kurtzman’s assistant editor. Here, Gilliam met a British comedian named John Cleese and, in 1969, was asked to join the Monty Python group as animator for the show’s opening credits. Gilliam’s outrageous cutout animations worked well with the group’s comedy routine. His ability to transform images of mundane objects into outrageous “actors” not only entertained his audiences but has demonstrated what stop-motion collage animation was capable of achieving. Terry Gilliam also became involved in directing live action during the 1970s and 1980s. Quirky stage sets, bizarre costumes, and puzzling camera angles are seen in Jabberwocky (1977), Time Bandits (1981), Brazil (1985), The Age of Reason (1988), and The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1989).

In 1977, Richard Alan Greenberg and his brother Robert founded R/Greenberg Associates. Richard, a traditionally-schooled designer, established a name for his company by “flying” the opening titles for the feature film Superman (1978). This sequence demonstrated an early example of computer-assisted effects that enabled the animation of three-dimensional typography. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Richard Greenberg designed title credits for features including Family Business (1989), Flash Gordon (1980), Altered States (1980), Another You (1991), Death Becomes Her (1992), Executive Decision (1996), and Foxfire (1996). Many of these titles are treated as visual metaphors that set the tone of the movie.

For the past four decades, groundbreaking title sequences for classics such as Dr. Strangelove (1964), The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), and A Clockwork Orange (1971) earned Cuban-born filmmaker Pablo Ferro a reputation as a master of title design, along with legendary designer Saul Bass. During his advertising career in the 1950s, Ferro introduced several techniques to the commercial film industry including rapid-cut editing, hand-drawn animation, extreme close-ups, split-screen montage, overlays, and hand-drawn type. Many designers claim that his quick-cut technique, in particular, influenced what later became known in television as the “MTV style.” In the opening sequence to the film To Die for (1995), Ferro developed the leading character through a montage of newspaper and magazine covers. (Nicole Kidman is so desperate to be a television newscaster that she convinces her lover to kill her husband so that she can pursue her career.) Pablo Ferro’s revitalization of hand-lettered movie titles and classic broadcast animations such as NBC’s Peacock and Burlington Mills’ “stitching” logo also became his trademarks.

Influenced by Pablo Ferro and Saul Bass, Kyle Cooper was one of the first graphic designers to reshape the conservative motion picture industry during the 1990s by applying trends in print design and in-corporating the computer to combine conventional and digital processes. After studying under legendary designer Paul Rand at the Yale University School of Art, he worked at R/Greenberg Associates in New York and contributed to the title sequence for True Lies (1994). In 1995, his opening credit sequence for David Fincher’s psychological thriller Se7en, which expressed the concept of a deranged, compulsive killer, immediately seized public attention. Today, it is regarded as a landmark in motion graphic design history.

After designing the opening for John Frankenheimer’s interpretation of H.G. Wells’s novel The Island of Dr. Moreau (1996), Kyle Cooper, Chip Houghton, and Peter Frankfurt founded Imaginary Forces, a motion graphics studio in Los Angeles.

Motion Graphics in Television

Early cinematic techniques that were used in experimental avant-garde film and movie title sequences became adopted in broadcast motion graphics, as television became a new medium for animation.

Harry Marks and network identities

By the late 1960s, most prime time television content was produced on color film. Tape recording technology also became available, and color videotape machines and tape cartridge systems were offered by RCA, providing stations with a reliable method of playback. Broadcasters stretched the limits of portability with large cameras and record ers. Program relay by satellite also emerged, giving viewers live images from all over the world. When there were just three television networks, brand identity was easily captured in three signature logos: NBC’s Peacock, CBS’s Eye, and ABC’s round logo designed by Paul Rand.

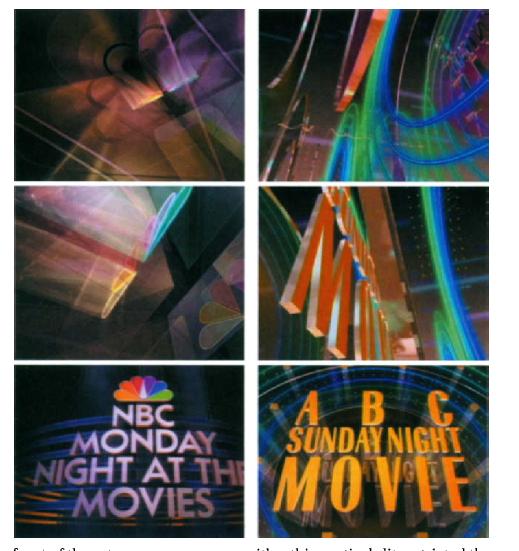

During that time, Harry Marks, who was working for ABC, conceived the idea of the moving logo and hired Douglas Trumbull, who pioneered the special effects in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), to assist him in his endeavors. Trumbull’s slit scan camera, which he had developed as an extension of John Whitney’s work, was mounted on a track and moved toward artwork that was illuminated on a table. In

1.26 Frames from NBC’s Monday Night at the Movies and ABC’s Sunday Night Movie by Dale Herigstad (1989). Courtesy of Harry Marks/Pacific Data Images and NBC.

front of the art, an opaque screen with a thin vertical slit restricted the field of view of the camera to a narrow horizontal angle. Although this process was laborious and expensive, it introduced many graphic possibilities into the broadcast world. The animated opening sequence to ABC’s Movie of the Week was a major accomplishment and captivated audiences nationwide. As a precursor to modern digital animation techniques, it brought about a major graphic design revolution.

Summary

Optical devices that emerged throughout Europe during the late nineteenth century demonstrated the phenomenon of persistence of vision, which involves our eye’s ability to retain an image for a fraction of a second after it disappears. Eadward Muybridge’s motion studies of animals and humans served as an aid to visual artists in helping them understand movement. In Britain, the Lumiere brothers took these experiments further and invented the first camera-printer-projector of modern cinema.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, artists began rejecting classical representation and desired to express space in geometric terms. Many desired to produce abstract, experimental animations that explored new techniques such as direct-on-film and collage During the 1970s, figures such as Stan Vanderbeek, John Whitney, and Robert Abel began exploring methods of computer animation for film titles. During the 1950s, graphic design pioneer Saul Bass became the movie industry’s leading film title innovator. His evocative opening credit sequences for directors such as Hitchcock and Preminger garnered public attention and were considered to be miniature films in themselves. During the 1960s, Friz Freleng’s opening cartoon for The Pink Panther (1963) and Maurice Binder’s openings for the classic James Bond movies became icons of pop culture. Terry Gilliam’s film titles, animated shorts, bizarre stage sets, costumes, and puzzling camera angles have set many design trends. In 1977, Richard Alan Greenberg and his brother Robert founded R/Greenberg Associates and established their reputation for their "flying" opening titles in the feature film Superman (1978). Many designers claim that Cuban filmmaker Pablo Ferro’s groundbreaking title sequences for classics such as Dr. Strangelove (1964)—in their use of rapid-cut editing and hand rawn type—influenced what became known in television as the “MTV style.” Influenced by Pablo Ferro and Saul Bass, Kyle Cooper was one of the first graphic designers to reshape the conservative motion picture industry during the 1990s by applying trends in print design and incorporating the computer to combine conventional and digital processes. In 1995, his credit openings for David Fincher’s psychological thriller Se7en immediately seized public attention and to this day is regarded as a landmark in motion graphic design history.

Early cinematic techniques that were used in experimental avant-garde film and title sequences became adopted in television. Harry Marks, who was working for ABC, conceived the idea of the moving logo and hired Douglas Trumbull, who pioneered the special effects in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), to help him animate the sequence to ABC’s Movie of the Week, which captivated audiences nationwide and brought about a major graphic design revolution