12 motion graphics sequencing

synthesizing the content

The process of sequencing in motion graphics can provide visual rhythm, enhance narrative, create emotions, and enable you to construct and restructure time and space. Time can be dramatically condensed from a period of several weeks into minutes or seconds. Space can be radically altered, jarring viewers between different environments to empower them and give them a sense of omnipresence. Further, sequencing can attribute new meanings to the subject being portrayed, making it more memorable and perhaps even life-changing.

“The essence of cinema is editing, its the combi-nation of what can be extraordinary images of people during emotional moments, or images in a generai sense, put together in a k,nd of alchemy.”

—Francis Ford Coppola

Editing: An Overview

The technique of editing has been alive for years, giving much creative potential and power to motion designers. In film and video, it involves the coordination and joining of multiple shots, each shot consisting of a series of frames that occupy screen space and time. In motion graphic design, it is the process of linking two or more motion graphic sequences or two or more views of the same sequence into a cohesive whole.

“To edit, means to organize pieces of film into a film, to ‘write’ a film with the shots, and not to select pieces for ‘scenes.’”

—Dziga Vertov

Traditional linear editing involves a linear tape-to-tape process in which specialized equipment, such as videotape recorders (VTRs), switchers, and mixers, are used to sequence footage into a finished production. Today’s flexibility of nonlinear editing allows you to digitally access and modify frames of footage without altering the original source. (In contrast, the “cut and glue” technique of film editing is destructive, since the actual film negative is cut.) Nonlinear editing is performed on standard desktop computers or on specialized hardware systems (such as the Media 100 and Avid) that can process high-resolution data in real-time. Consumer-level video editing applications, such as Final Cut Pro (Apple Computer, Inc.) and Pinnacle Studio (Pinnacle Systems, Inc.), offers nonlinear editing, compositing, and special effects tools, while motion graphics programs, such as After Effects, offer standard but less sophisticated editing capabilities. Some editing software can be downloaded for free, and others, like Microsoft’s Windows Movie Maker or Apple’s iMovie, are included in the operating system.

Editing can be broken down into two processes: 1.) selecting and 2.) sequencing. Selecting involves choosing which actions or events will be in the final production. This depends upon your contextual factors, such as the subject being communicated, the intent of the communication, the target audience, and the method or style that will be used to deliver the message. Sequencing involves linking the actions or events together in a way that clarifies and intensifies the information, to create a clear and memorable experience for viewers.

From classical Hollywood films to avant-garde filmmaking and experi-mental animation, different editing styles throughout history have defined the narrative and nonnarrative form of filmmaking and have inspired trends in motion graphics.

Historical Perspective

Editing itself can dominate a film’s style. During the 1920s, film theorists began to realize what film editing could achieve, and it quickly became the most widely discussed film technique to successful cinema Sergei Eisenstein’s early productions, such as Strike, Potempkin, October, and Old and New, demonstrate the attempt by young, experimental Russian filmmakers to make editing their fundamental principle in film during the 1950s.

In the past, video editing was a linear process that required careful planning in advance. Today, dimple cuts, inserts, superimpositions, and masks can be performed digitally in any order, offering a greater degree of flexibility and precision in the timing and synchronization of events Additionally, they allow motion graphic designers to readily alternate between multiple sources of footage in a more spontaneous and creative manner.

Editing is established through the use of cuts and transitions. Both of these techniques necessitate a visual strategy that requires patience, sensitivity, and intuition. It is important to remember that intuitive judgments can lead to conscious decisions.

Cuts

The cut has been the most widely used editing technique since the invention of film. It produces abrupt, instantaneous changes of space or time in a sequence, or between sequences, of images, actions, or events. Unlike transitions, they do not occupy time or space. Cutting between images with different points of view or different types of framings can contribute to the emotional impact of the theme. If poorly used, however, cuts can create undesirable results that look like mistakes rather than intentional, artistic decisions. As discussed later in this chapter, rhythmic cutting can help determine pace and regulate event density. For example, the frequency of cuts in an MTV spot or a short television commercial might establish sensory bombardment of visual information, whereas the more limited number of cuts in a documentary nature film may preserve its modest, academic integrity.

The soundtrack in music rodeos often aids motion graphic designers in determining where visual cutting should occur.

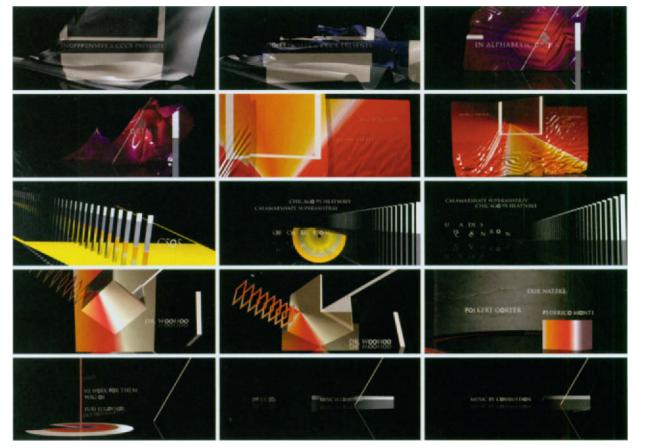

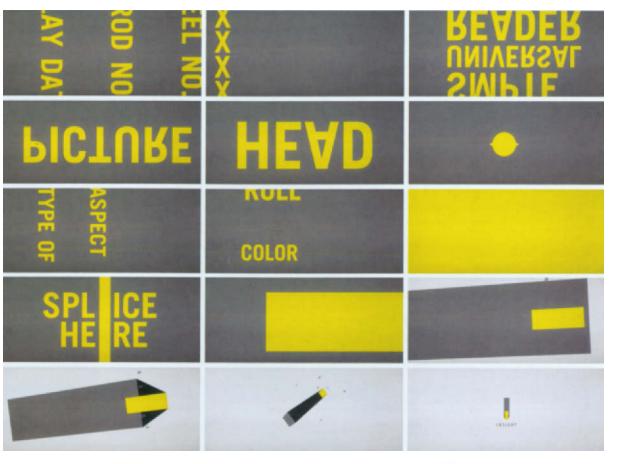

In figure 12.1, simple cuts between segments of digitally-projected images and credits conform to subtle changes in the music to create a quiet sense of drama and suspense. In contrast, the rapid, rhythmic cuts in the typographic sequence in figure 12.2 give the company’s identity a high intensity feel.

12.1 Frames from the opening tides for OFFF’s BCN 06 event. Courtesy of Renascent.

Crosscutting involves cutting between different actions that occur at the same time to keep viewers informed of two or more events. In traditional chase scenes it can build tension by shifting back and forth from the pursuer to the pursued. As a result, both lines of action are tied together, indicating that they are concurrent. This technique can enrich a narrative continuity and alter time by accelerating or slowing down the main action. It also gives viewers a range of knowledge that is greater than that of the subject. Although it creates some spatial discontinuity (discussed later in this chapter), it can link separate events together to produce a sense of cause and effect.

Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery f (1903). a landmark of American silent film. is on early example of parallel editing. Many of the shots depend upon our ability to imagine that the crosscut scenes extend into off-screen space where events continue to develop whether we are present to view them or not.

Parallel editing involves crosscutting between independent spaces or events to suggest that they are taking place simultaneously. It also creates a sense of omnipresence, giving viewers unrestricted access to onscreen and offscreen space by alternating between events from one line of action with events from other places. It can also create parallels

12.2 Frames from a motion ID for Insight, a company specializing in behind-the-scenes film production. Courtesy of Renascent.

by suggesting analogies to draw the viewer into the action. Parallel editing is basic to motion picture editing and has been used to describe relationships between images and their corresponding Insight, a company specializing in behind-the-scenes film production. Courtesy of Renascent. soundtrack. The technique of counterpoint functions in the opposite way—to show relationships between images that are not parallel to the accompanying soundtrack. Both of these techniques have been used for creating suspense and altering the passage of time.

A cutaway shows an event or sequence of events that are unrelated to the main event. Its objective is to temporarily draw attention away from the action as it continues to unfold in offscreen space and time. In Heritage, a personal film about themes from the Old Testament, a sequence showing a close-up of a Torah reading precedes a shot of an Israeli dancer moving to the sound of his voice. Cutawaysare also used to establish symbolism, such as an image of a dancing flame followed by a rabbi reciting a prayer (12.3).

12.3 Frames from Heritage. Phase III, by Jon Krasner. This sequence uses cutaways between a Torah reading, an Israeli dancer, a flame, and a rabbi reciting a prayer. © Jon Krasner. 2007.

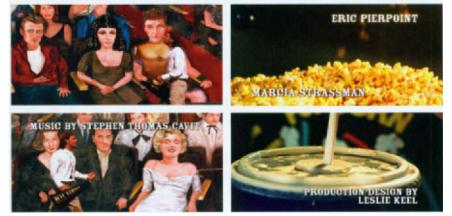

12.4 The opening titles to The Movie Hero (2003) employs cutaway views between the main talent. who believes that his life is a movie watched by an audience that only he can see. and images of movie theatre concessions. Courtesy of Shadowplay Studio.

Many believe that Russian filmmaker Lev Kuleshow, who helped establish the basis for montage during the silent film era. pioneered the technique of parallel editing by linking together different shots of actors who seemed to be looking at each other. although they were filmed on different Moscow streets. Many filmmakers have employed the “Kuleshov effect” by juxtaposing shots of disparate events to create a cohesion between different spaces or time zones.

As an alternative to cutaways, jump cuts produce abrupt changes or noticeable jumps in the positions or movements of elements against a constant background. (Alternatively, the ground can change abruptly while an element remains fixed in space.) Because there is a visible change in the content, it becomes obvious that part of the composition has been cut out. The illusion of continuous time is broken.

Jump cuts became popular narrative devices during the 1960s and continue to be used to accentuate rhythm, abbreviate time, signal emotional stress, or cause viewers to be momentarily perplexed. In a series of promos for Comedy Central’s hit series, Chappelle’s Show, a frequent use of jump cuts in the subject’s movement, positioning, and camera views works in concert with the background’s bold graphic shapes to express the sharp, defiant humor of the series (12.5)).

A flash cut is a rapid interchange between two shots to create a dramatic, psychological effect. Sometimes a single frame is enough to arouse fear or shock. Jump cuts and flash cuts are discussed later in this chapter with regard to establishing temporal discontinuity.

12.5 Frames from Comedy Central’s Chopelle’s Show. Courtesy of Freestyle Collective.

Transitions

Transitions are alternatives to using straight cuts to link sequences of images or actions. Both in their style and in their speed, they allow a smooth flow between changes by providing a link between sequences. Whether transitions are generated by the camera during capture, produced optically in a lab, or digitally on a computer, they play an influential role in the timing of events by providing gradual changes between sequences over a designated time period in a composition. Aesthetically, it is essential that you exercise artistic discretion in using transitions appropriately and in moderation without becoming overly dependent upon their effects.

The most common types of transitions are dissolves, fades, and wipes. Dissolves are frequently used to indicate passages of time. They in-volve smooth, gradual changes of opacity between two overlapping events so that the ending frames of the first event incrementally blend with the opening frames of the next. This method of transition softens abrupt changes between frames, producing the effect of one sequence melting into the other. (In sound, a dissolve is commonly referred to as a crossfade.) As mentioned later in this chapter, using dissolves can aid continuity because they act as thematic or structural time bridges between events.

A dissolve’s length can produce various effects. For example, a slow dissolve can indicate a long time lapse, while a quick one can convey a brief passage of time. In a bumper for Showtime Networks, slow to enhance the concept of flowing silk (12.6)). If a dissolve is frozen midway, a superimposition results, producing ghosted images of two different sources. (Stopping a crossfade would produce a mix of two different audio sources.)

12.6 Frames from a bumper for Showtime Networks. Courtesy of Giant Octopus.

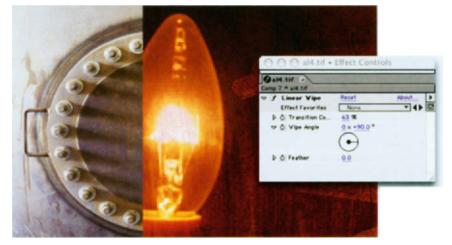

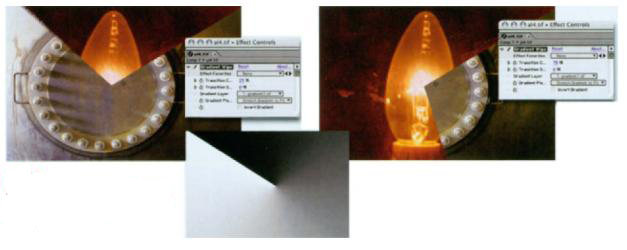

A fade is a dissolve from or to black (or any solid color). It is achieved by gradually increasing the exposure until the image reaches its full brightness capacity. A fade-out is obtained by gradually decreasing exposure until the last frame is completely black. Fades are generally used at the beginning or end of major events to signify a major change in content, time, or space. As such, they represent a distinct break in a story’s continuity. The length of a fade is usually taken into strong consideration with regard to the timing and mood of the overall piece. In the title sequence to Mansfield Park, the use of fades between long durations of events effectively establishes the tone of the film (Chapter 6, figure 6.21). The opening titles to the film Moth employ fades between the strange transformations of rotating macro close-ups of light bulb filaments and the opening scene, to indicate that a passage of time has passed (12.7)). In a bumper for a weekly ice hockey series broadcast across NTL’s cable network, short fades are emulated through actual players skating in and out of a theatre spotlight in a blacked out ice hockey rink. Small increments of time between the actions reflect the passion and excitement of the game (12.8)). In a student project involving a fictional product advertisement, Eric Eng’s incorporation of fades and dissolves between shots of varying camera angles focus on the subject’s organic forms to express its power and beauty (12.9)).

In most motion graphics and digital editing applications. the parameters of built-in transitions can be altered in terms of thew duration, size, and orientation, depending on the type of transition.

Wipe transitions were common in the 1930s, involving an image literally pushing the previous image off of the frame through a horizontal, vertical, or diagonal movement. A flip (or flip frame) is a type of wipe in which the images appear to be cards flipped one after another. Wipes

12.7 Frames from the opening tides for Moth. Courtesy of Applied Works. © Amulet Films Limited 2004. www.amuletfilms.com.

12.8 Frames from the opening titles for Inferno. Courtesy of Applied Works. © Sportfact Ltd 1997.

12.9 Frames from a fictional product ad by Eric Eng, Rochester Institute of Technology.

can move in any direction, open any side, start in the center and move outward toward the frame’s edges or vice versa. Additionally, they can begin as one shape and morph into another. (Split-screen effects are often created by wipes that are partially completed.)

In addition to standard dissolves, fades, and wipes, most applications offer a variety of complex graphic transitions that can be customized and animated; they can flip, bounce, and crush their way into the frame. Transitions such as clock wipes, checkerboards, and Venetian blinds typically are included in most consumer packages, while more complicated transitions can be generated from actual black and white images or alpha channels. It is critical to exercise mature aesthetic judgment and use these types of transitions appropriately with respect to the integrity of your concept and design.

12.10 A linear wipe reveals new imag-ery in a specified direction. For example, at 90 degrees the wipe travels from left to right.

12.11 After Effectd’s gradient wipe wipe references the luminance values of an overlying image.

12.12 above:

below: Adobe After Effects’ block wipe Susan Detrie’s quiet. elegant. ani creates the effect of an image mated transitions for Fine Living disappearing in random blocks.

12.13 below:

Susan Detrie’s quiet. elegant. ani mated transitions for Fine Living Network consist of simple. two dimensional graphic planes that move fluidly across the screen at various angles. Courtesy of Fine Living Network and Susan Detrie.

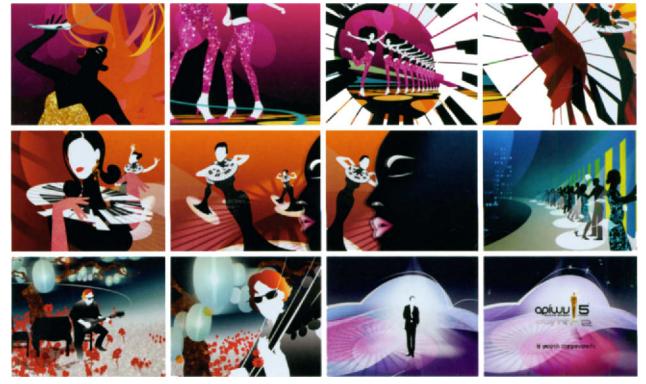

Last, transitions can involve using images from one scene to introduce images or events in the next. A great example of this is a design for a trailer and on-air package for the 2006 Arion Music Awards (12.14)). The concept behind the project was to personify various categories of music in a fresh, contemporary way through the use of colorful ani-mated illustrations. There are several image transitions that smoothly link the events. For example, a ring of piano keys enters into the frame to form a mask that encloses the underlying background imagery. The mask becomes smaller and quickly transforms the imagery into the next scene featuring several female dancers wearing a piano-like collar around their necks. An extreme graphic close-up of a woman’s profile enters the frame from the right and moves across the screen toward the left, its color shifting us into a new space. Another transition in scenery occurs when a medium shot of a male figure playing guitar zooms into a space that becomes the last scene featuring a television host that turns into the music video award, a golden trophy.

12.14 Frames from the trailer and on-air package design for the Arion MusK Awards. organized by the Mega Channel, the first corporate channel w launch on the Greek airwaves. Courtesy of Velvet.

Figure 12.15 illustrates another example in a network rebrand for BET J, a cable television channel intended to showcase jazz music of black musicians. Freestyle Collective aimed to create a design that expressed the soul and funk of jazz. The device of frame mobility (discussed later in this chapter), emulated with a continuous zoom out, was used to create smooth transitions between three different levels of space: 1) a woman aboard an airplane, 2) the airplane itself, and 3) a scene featuring a road, landscape, building, and the airplane flying off in the distance. Another composition for BET J uses a pair of musical symbols as a natural means of transition into a graphic cityscape. In a header for 50 anon bo es nada, a documentary series that narrates the history of the Spanish television, Ritxi Ostariz’s transitions are created by zooming into a portion of an image that becomes the ground for the next scene which features different elements (12.16).

12.15 Frames from a network rebrand for BET J.a spin-off cable television channel of BET (Black Enter-tainment Television), intended to feature jazz music. Courtesy of Freestyle Collective. ![]()

12.16 Frames for 50 ones be es nod0. Courtesy of Ritxi Ostariz.

Pictorial transitions can also be created by cutting or dissolving between an image at the end of one sequence and a similar image at the beginning of the next, as illustrated in Hillman Curtis’ Flash advertise ment in figure 12.17.

12.17 Frames from “Greenville,” an online Flash advertisement for Craig Frasier/Squarepig.tv. Courtesy of hillmancurtis, inc.

Mobrle Framing

Mobile framing offers an alternative method of constructing motion graphics sequences versus standard cuts and transitions that are associated with editing. The camera techniques described in Chapter 6 can be employed physically or digitally to break up a composition into various segments. (Figure 12.18), for example, shows a continuous, unedited motion graphics sequence of three-dimensional forms that move uniformly as the “camera” zooms out and rotates our point of view to establish a final frontal view of the image.

12.18 Frames from a logo animatio’ for Heidelberg. Courtesy of Renascent.

Frame mobility can also impact our sense of pace and rhythm, since it occupies duration in a composition. The velocity or speed in which the camera moves is an important consideration. A quick pan away from a subject can arouse curiosity or wonder, while an abrupt movement can induce the element of surprise or shock. Music videos often organize the velocity of camera moves to the underlying rhythm of a song.

Establishing Pace

Pace—a vital, yet elusive, aspect of sequencing—represents the speed in which content is presented. It functions to deliver messages in the most engaging and meaningful way, taking into consideration the duration that events exist onscreen and the manner that cuts and transitions are used to link them. Film and video editors are expected to know how to choose an editing pace that establishes the mood of the content. Many of today’s feature films and TV shows are often paced fast, allowing you to follow the basic story but enticing you to watch it again. Subtle events that are missed can be enjoyed during a later viewing. On the other hand, documentary films and training videos are usually slower paced, since their objective is to deliver information clearly the first time around without losing the audience’s interest.

A composition’s pace can change over time to communicate different aspects of a story. In the opening titles to the television miniseries, The Path to 911 (2006), the pace picks up as the film progresses toward an extreme close-up of the World Trade Center. Each shot is heightened to inform us that an event is about to occur. Mundane scenes of a person’s morning journey to work become transformed into images of large groups of people that are juxtaposed with close-ups of feet, hands, and bird’s-eye views looking down into the city’s streets (12.19).

12.19 Frames from the opening titles to The Path to 911. a miniseries that aired on ABC on September 10.2006 and September II.2006. Courtesy of Digital Kitchen.

tempo and event density

In music, tempo refers to the speed that beats occur in each measure. In film, animation, and motion graphics, tempo refers to the speed that events occur over time.

If you are unsure of the subjective feel that you want for your composition’s pare. try listening to different genres of music anal you find one that has a prevailing tempo that expresses the mood of your concept

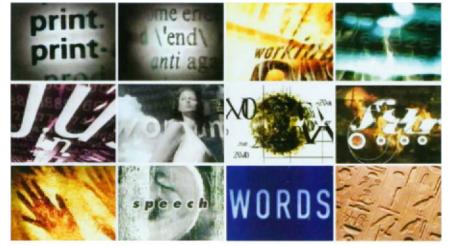

Most of us have experienced that a slow tempo can support a languid pace, while a fast tempo can establish a brisk one. Moderate tempos can reinforce a sense of positive, forward progress and can be applied to a wide range of styles, from the energy of a corporate presentation to cheerful good feelings in a travel spot. The tempo you choose can determine and regulate the number of cuts and transitions that will be applied to your composition or the event density. For example, the large number of cuts in many car commercials create a high-density, edge-of-the-seat impact, while a smaller number of cuts in a nature documentary may generate a tranquil, serene atmosphere. David Carson’s experimental film, End of Print, illustrates a high-density composition through short, rapid bursts of disassociated, disjointed images and typographic elements. Carson’s precise, dynamic editing to the soundtrack creates an information overload that bombards us with information (12.20). In contrast, the slow tempo of The Path to 911 (12.19) is characterized by minimal cuts between segments.

12.20 Frames from End of Print. based on the book. End of Print 1 1995 ] by David Carson and Lewis Blackwell.© David Carson.

transition speed

The speed that transitions take place is another factor that can help establish and regulate pace. The duration of dissolves, fades, or any other types of transitions that take place between events may affect the composition’s overall pace more than the style of transition you choose. Generally speaking, fast-paced compositions with rapid transitions across small ranges of frames can deliver snappy, energetic effects, while slow fades or dissolves that occur over long time intervals can produce a more deliberate and dignified feel.

Establishing Rhythm

In music, listening to the repetition of beats and accents in a song can identify its rhythm.

Rhythm and pace are directly related. A rhythm with a steady, consistent pace can be effective in that it is predictable enough for viewers to feel subconsciously and tap their feet to. On the other hand, a rhythm with an inconsistent, variable pace can be effective because it breaks predictability, treating viewers to the element of surprise. From traditional cinema to MTV,

From traditional cinema to Mnl: rhythmic editing (also referred to as dynamic editing) has been applied to both narrative and non narrative forms of film and motion graphics. It has also been applied to both continuous and discontinuous approaches to editing. During the early twentieth century, avant-garde Cubist and Dada filmmakers, as well as filmmakers from the French Impressionist and Soviet montage school subordinated narrative concerns to developing complementary editing approaches to establish rhythmic patterns. (Even classical

Historical Perspective

French Impressionist and Soviet avantgarde filmmakers often subordinated narrative to pure rhythmic editing In French Impressionist films, rhythmic editing was often used to depict inner turmoil or violence. for example, the impact of the train crash in the film La Roue was conveyed through a series of accelerated shots that became shorter and shorter over time.

Rhythm was also a key element in the work of Surrealist filmmakers such as Hans Richter, who combined improvisation and innovative camera usage with a sense of formal Constructivism to produce continuous rhythmic themes throughout his films.

Lev Kuleshov’s The Death Ray (1926), Sergio Eisenstein’s October (1927),and many of the films of Alfred Hitchcock also show how rhythm can dominate narrative.

Hollywood cinema explored the rhythmic use of dissolves in mon-tages.) When sound films became the standard, rhythmic editing was evident in musical comedies, dance sequences, and dramas. During the 1960s, fast cutting to the beat of a tune was used in television commercials for soft drinks and during the 1980s in music videos, in which a rapid succession of highly stereotyped images were cut to match the rhythm of the soundtrack.

Experimental filmmaker Marin Amok( took rhythmic editing to the extreme. Piece Touchce (1989). an 18-second sequence taken from o 1950s American “8” mane, was reproduced frome-by-frvme and manipulated according to its temporal and soma) progression. In Passage a I’acte (1993), a postwar family breakfast scene from the 1950s ft lm. To Kill a Mockingbird. is transformed into a disturbing, compulsive, rhythmic sequence of repetitive movements and sounds. The sound of the opening and dosing of the screen door mimics gunfire. and repeated shots of the family members who. like a broken record, yell out parts of words or twitch bock and forth seem to pulsate to on underlying continuous. monotonous beat

continuous rhythm

In music, dance, or any other form of time-based, artistic expression, most of us seem driven by rhythms that are discernable, steady, and constant. Many filmmakers, animators, and motion graphic artists who have been inspired by avant-garde cinema and Eisenstein’s experiments with montage have strived to create uniform, rhythmic structures in their compositions.

timing

In motion graphics, timing can be considered in establishing a steady, continuous rhythm. In music, timing differs from tempo, in that it indicates the number of beats in a measure; tempo describes the speed of the beats in each measure. If you are a musician or have a basic knowledge of musical composition, you may already know that a 4/4 timing yields a different tap-of-your-foot-to than a 3/4 time signature, which, if played slowly, can feel like a waltz.

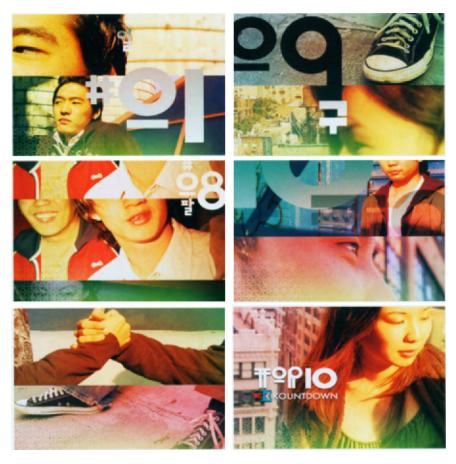

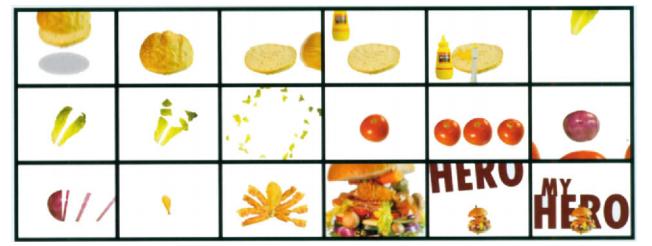

If you are editing to music, the timing of beats and accents can help determine the underlying visual rhythm. Alternatively, you can recite a verse in your mind or listen to the beat of a metronome to create a sense of timing if sound is not available. In figure 12.22, the timing of the cuts between photographs of urban hipster scenes and dreamlike live-action imagery was precisely edited to match the piece’s soundtrack. In a student project entitled My Hero, Eric Decker gave careful consideration to the cuts between segments and the timing in which various foods and condiments enter and leave the frame. Both are precisely edited to match the rhythm of the soundtrack (12.22).

In music, rhythm describes how sounds of varying length and accentuation are grouped into patterns called measures. The timing of notes in each measure is independent of the tempo that governs the composition’s pace. If you tap your foot faster or slower to the beat of a tune, the rhythm does not change — only its tempo.

frame duration

The duration that a composition’s segments remain onscreen is one of the most basic temporal considerations of rhythmic editing, allowing you to govern the amount of time that viewers are allowed to see and interpret the content.

12.21 Frames from a network package for MTV K. the First premium channel under the MTV World family geared specifically toward young Korean-Americans. Courtesy of Freestyle Collective.

Combinations of live action video. still photos and vibrant animations are edited to match the timing of the soundtrack to evoke the young. cool lifestyle that has become synonymous with MTV culture

12.22 Frames from My Nero. by Eric Decker. Produced in “Dynamic Typography” at the Rochester Institute of Technology. Professor Jason Arena.

A segment in a composition can be as short as a single frame or as long as thousands of frames, running for many minutes. One of the simplest ways to construct a consistent rhythm is by making all the segments approximately the same duration. Regardless of the content, related or unrelated images, actions, or events that are presented in equally spaced time intervals, will produce a steady rhythm that unifies them into a cohesive whole. This also means that the number of cuts and transitions that are used (or the event density) are distributed throughout the composition in equal intervals. A silent viewing of Man Ray’s avant-garde film, Emak Bakia (1926), illustrates this concept. The romantic, underlying musical rhythm that prevails throughout the film is largely due to the fact that the durations of thematically related mov-ing objects and figures on the screen are similar.

Early cinema tended to rely on shots that were fairly lengthy. Shots eventually became shorter with the practice of continuity editing, and by the early 1920s, American films had average shot lengths of five seconds. The advent of sound film stretched this to about ten seconds.

repetition of image and action

Cutting or transitioning between recurring segments that have matching or similar images or actions can also introduce uniform rhythm. This can help create a sense of structural continuity and maintain a sense of pace and cohesiveness in a composition.

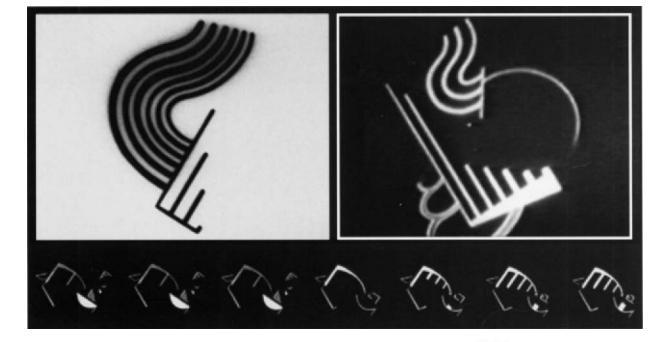

Experimental animations from the 1920s relied heavily on the concept of repetition to achieve rhythm. Fernand Léger’s and Dudley Murphy’s Cubist film, Ballet Mécanique (1924), builds a rhythmic structure from juxtaposed mundane objects that are treated as motifs and are re peated in different combinations in rapid succession. Highly rhythmic sequential movements of spinning bottles, faces, hats, and kitchen utensils, which taken out of their original context, recur in highly organized arrangements. Body gestures and facial expressions seem to be mechanically orchestrated to move in concert with the film’s soundtrack. Graphic contrasts, frame mobility, and rapid sequences of close-ups, medium close-ups, and extreme close-ups illustrate a complete abandonment of the continuity system in favor of achieving a dance-like choreography of rhythm (12.23). In Viking Eggeling’s Symphonie Diagonale (1924), each movement was choreographed to a steady, mechanical tempo. Rhythm is articulated by the manner and speed by which geometric elements appear and disappear in the frame, along with the duration for which they remain on the screen. In many instances, figures build over time, line by line, and varying shades of gray create the effect of images fading in and out to the underlying musical score. The arrangement of different themes within the piece can be compared to the orchestration of a symphony (12.24).

12.23 Fernand Léger’s Ballet Mécanique (1924) demonstrates a consistent rhythmic progression of abstract images and actions.

Image and action uniformity was also a key element in Hans Richter’s approach of combining spontaneous improvisation with formal organization. Throughout his Surrealist film, Ghosts Before Breakfast (1927), a strong underlying rhythm is maintained in the relative speeds that elements move from shot to shot. Equal numbers of characters or objects also remain constant throughout the film to preserve rhythm. For example, three men in the one scene follow three hats in the previous shot. Additionally, shapes that fill the frame are spaced apart at equal intervals. In one particular scene containing five guns that are rotated to form a pinwheel image, the guns are spaced equidistant from each another. The rhythm is also present in the speed at which they turn. Recurring images of flying hats also establish a continuous rhythm throughout the composition.

12.24 Filmstrip from Viking Eggehng’s Symphonie Diagonaie (1924), Taking almost four years to complete. this lrame-hy-frame animation showed a strong correlation between music and painting in the movements of figures that were created from paper cutouts and tin foil Viking Eggeling died in Berlin approximately two weeks after his film was released

In musical arrangements, individual notes and durational sonic patterns ((notes drat repeat at regular intervals an contribute to a compost iron’s rhythmic flow to emote unity. in classical music, certain themes may be duplicated to give the piece a unique personality that differs front other arrangements. Without repetition. a musical composition can stray away aimlessly in too many directions, lacking a facus

In a bilingual on-air opener and program design for “DW Euromax” (12.25)), objects such as violins, shoes, chandeliers, chairs, and fountain pens are strategically arranged into moving patterns or more complex abstract shapes. The elements move at constant speeds and are spaced apart at equal intervals. The repetition of these elements in consecutive segments ties the film together into a unified composition.

12.25 Frames from “DW Euromax.” a bilingual on-air program design. Courtesy of Velvet. ![]()

variable rhythm

Rhythm does not have to be uniform; in fact, it can change over time in order to vary the mood of a composition. Unlike dance music, where the rhythm is steady and continuous, the variety of tempo changes throughout a piece of classical music characterizes its different phases.

Variation in rhythm allows new material to be introduced into repetition. It can help break predictability and be used to emphasize a particular point of interest. It can also allow you to simply stay in synch with the soundtrack if your piece is a music video. Even if the “beat” of the soundtrack is steady and constant, introducing changes in the way images and actions are presented, as well as tempo, event density, and frame duration of content can add variety. In Léger’s Ballet Mécanique, the relative scale of objects in the frame changes through the use of close-up, medium close-up, and extreme close-up shots. Additionally, close framings are used to isolate and emphasize form and texture, while other framings, such as upside-down shots and masks, introduce rhythmic variation.

emphasis

Emphasis marks an interruption in the fundamental pattern of events. It can also break predictability and define a point of focus. In music, emphasis is achieved by providing accents in order to make certain notes or combinations of notes stand out. In character animation, it is used to exaggerate movement. In motion design, it is used to contribute toward the visual hierarchy. For example, an element that flies or tumbles into the frame calls more attention to itself than one that moves slowly and uniformly.

varying event frequency and tempo

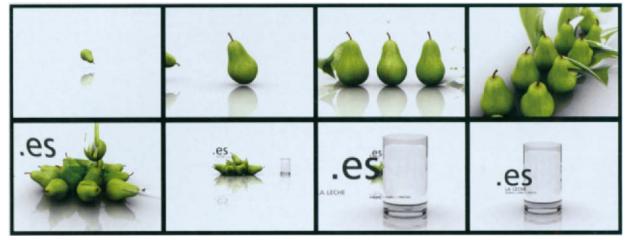

Showing the same event repeatedly, but in a different way, can block the viewer’s normal expectation about the narrative. In fact, it can invite viewers to focus on the actual process of assembling the story. One way to achieve this is by changing the tempo in which events are presented. This also serves as an easy way to introduce rhythmic possibilities. Slow motion seems to interrupt a composition’s flow, because it presents a close-up of time (similar to holding your breath), while fast motion seems to accelerate you forward in time. In a broadcast commercial for a supermarket in Spain, Joost Korngold of Renascent was given the task of creating seamless transitions between groupings of pears, a glass of milk, and several oranges to illustrate the process of waking up in the morning, driving to work and starting the day. Based on a rough storyboard sketch, his challenge was to make the transitions between the elements as interesting as possible by creating harmonious movements of the objects and the camera. The incorporation of fast motion and accelerated camera movements creates an exciting, unpredictable visual rhythm against the underlying, steady beat of the soundtrack (12.26).

12.26 Frames for "Ervsk’ a broad-cast commercial for a Spanish supermarket Courtesy of Joist Korngold. cc:, Renascent 2007.

In TV12’s PSA promoting vehicle safety, a brisk tempo is established through rapid jump cuts that occur during a rotated and zoomed-in view of a Roadsense Team vehicle. The tempo suddenly gives way to a steady but moderate pace that accompanies a layering of complex road signs that move uniformly across the screen 12.27).

In the network package for MOJO (Chapter 8, figure 8.34), discon-tinuous rhythm was deliberately used to create an edgy attitude and almost disturbing feel in order to arouse anticipation. In fact, it was intended to invoke precisely the opposite reaction that you would get from watching the Hallmark Channel or Martha Stewart. Rapid cuts between images occur at an unsteady pace, changing according to the soundtrack. Instead of using music, motion graphics company Flying Machine implemented pure sounds to create strong rhythmic con-trasts. One particular segment shows a dramatic contrast in which a shot of a group of rapidly twisting and turning kitchen utensils is immediately followed by a slow pan of a sensuous female torso and a car. The repetition of events, such as alcohol being poured into a glass, film projections, and extreme close-ups of female body parts, occurs at an unpredictable rate to reinforce the element of surprise.

varying frame duration

Controlling the rhythmic succession of images, actions, or events by manipulating their onscreen duration provides plenty of opportunities to introduce variety into a composition’s rhythmic structure. Regardless of the time that images, actions, or events “live” in the frame, if their onscreen durations are similar, the predictability of the rhythm can grow cumbersome if they are long or become irritating if they are short. (Keep in mind that this is not always true. Similar durations of events can establish a pleasing, underlying musical rhythm, as in Man Ray’s Emak Bakia.) Combining sequences consisting of different frame lengths can create irregular rhythms. For example, shortening or lengthening each consecutive sequence can produce an accelerated or decelerated rhythm, which can produce the effect of drama and tension, leading viewers to expect a change in narrative action. Mixing and matching short and long sequences can serve to renew the audience’s attention and refresh their interest. (This means that the distribution of the cuts and transitions that link a composition’s segments can also be variable).

12.27 Frames from TV12’s “ICBC Roadsense.” Courtesy of Tiz Beretta and Erwin Chiong.

pause

In addition to incorporating inserts and cutaways, pauses can also vary a composition’s rhythm and pace. A pause can be a series of black consecutive frames between two segments or a specified time interval where the action remains frozen on the screen. Pauses can also be used to give viewers time to rest between events, emphasize a point, create expectations or tension, or help regulate the viewer’s perception of the flow of time.

Birth, Life, and Death

In Chapter 5, birth and death describe how elements are introduced into the frame and the manner in which they leave the frame. “Life” describes their duration or how long they live or reside in the frame. In sequencing, all of these factors need to be given considerable at tention. The sequential or transitional continuity that is established in many of the storyboard designs in Chapter 9 is largely due to the method in which elements appear on the screen and how they leave the frame. This allows transitions between events to flow smoothly and be easily deciphered without even seeing their actual movement.

Introduction and Conclusion

The significance of a story’s beginning and conclusion cannot be overstated. Critical thought must be given to how you plan to capture your audience’s attention and keep them engaged throughout the duration of the piece. Your opening and closing sequences must establish both a strong start and a strong finish. They should be given at least twice as much attention as the middle of the composition. Beware of overloading these segments with too many special effects and transitions; sometimes simplicity can be most effective (less is more) in establishing and confirming the concept.

Summary

The technique of editing involves coordinating and joining multiple images, actions, or events into a cohesive whole. Cuts produce instantaneous changes between scenes. Parallel editing involves joining separate events together to produce a sense of cause and effect. Cutaways are used to shift the viewer’s attention away from the main action as it unfolds in offscreen space and time. Jump cuts produce abrupt changes in the positions or movements of elements, breaking the illusion of continuous time. Transitions are passages of time that allow gradual changes between events. For example, fades are used to signify major changes in content, time, or space, representing distinct breaks in a story’s continuity. Mobile framing through camera movement is an alternative to linking sequences through cuts and transitions.

A composition’s editing pace is based on the duration that events exist onscreen and the manner in which cuts and transitions are used to link them. Factors that help determine and govern pace are tempo, event density, and transition speed.

Rhythmic editing can be used to create continuity or discontinuity. Presenting events in equally spaced time intervals and establishing graphic and action uniformity between segments produces uniform rhythm. Varying a composition’s tempo, changing the duration of onscreen events, and inserting pauses can break predictability in order to maintain the interest of viewers.

Critical thought must be given to the principles of birth, life, and death as well as the story’s beginning and conclusion.