8 the sequential composition

designing in time

Every story must have a begining, middle, and end. The visual and sonic experience of images, actions, and sounds over time can allow it to unfold in its natural order of events. On the other hand, the sotry can be told in a different order, according to a completely different timeline.

Similar to musical conductors who choreograph sounds, motion designers orchestrate sequences of events and the manner in which images and type move and change over time, appear and disappear off the screen, and transition from one event into the next in every story.

—Tom Mdoreiy

Sequential Composition: An Overview

The mind compartmentalizes visual information, motion, and souhd into units. For example, in musical compositions, we structure sounds into predefined arrangements. In dance, we organize patterns of movement into highly refined sequences. The same is true in motion graphics; we “orchestrate” events into units or sequences that unfold over time and across space through movement and transition. This allows us to create order, build excitement, or arouse anticipation.

Sequential composing is a developmental process that, with dedicated thought and adequate planning, can enhance artistic expression and conceptual impact. The language of cinema can be used to tell stories in effective, meaningful ways.

Forms of Contie

Continuity throughout a composition generates the feeling that space and time are fluid and continuous. During the 1930s and 1940s, many narrative American films were produced and edited according to the classical continuity editing style. The approach was guided by explicit rules to maintain a clear, logical narration and relied heavily on spatial and temporal relationships between shots. Subsequent films, such as Singing in the Rain (1952) and Persona (1956), demonstrate a strict adherence to these continuity standards.

The application of continuity editing to motion graphics can allow you to be clear in your storytelling and delivery of information.

8.1 Frames from a Flash-based Web interstitial for SquarePig TV. This composition demonstrates an effective use of traditional cinematic continuity principles. Courtesy of hillmancurtis, inc.

spatial continuity

Continuity can be used to structure both on screen and off screen space in a way that preserves the viewer”s cognitive map. This means, simply, that the viewer”s sense of where things are in the frame and outside of the frame is coherent and constant throughout the composition. There should be a common space between consecutive sequences so that the viewer”s flow of attention is maintained without disruptions.

establishing context

Establishing a context prior to cutting between elements facilitates the preservation of spatial continuity. For example, if you establish a context of two people looking in the same direction, subsequent frontal close-up shots allow to us to perceive the direction of their gaze as continuing into off screen space (8.2). In figure 8.3, frontal close-ups of two people looking at each other continue the converging vectors that were previously established in a prior medium shot. When the context establishes diverging vectors, subsequent frontal close-ups continue our perception that they are looking away from each other (8.4). In the title sequence shown in figure 8.5, a humorous shot of two figures combating a fictional monster cuts to a frontal, close-up shot of one of the figures, revealing his expression of dread. The context that was established in the first scee allows us to interpret his gaze as being directed toward the monster-not at the viewer.

8.2 Spatial continuity of continuing vectors in subsequent close-ups.

8.3 Spatial continuity of converging vectors in subsequent close-ups.

8.4 Spatial continuity of diverging vectors in subsequent close-ups.

index and motion vectors

Index vectors are powerful structural elements that provide stability in a composition. In the sequential composition, they can preserve our sense of spatial continuity between consecutive images, actions, or events. The application of a continuing index vector in figure 8.6 is shown in a medium shot of a person looking to the right followed by a close-up in which the direction of her glance is maintained.

8.5 Frames from “HandleThe Jandal”,an opening title sequence for DIY NZ music video awards. Courtesy of Krafthaus Films (New Zealand).

In traditional continuity style editing in live-action film, scenes are constructed along an imaginary axis of action (also commonly referred to as the vector line or line of conversation), where the subjects are recorded from one side of a 180-degree line. The goal: to stabilize space. Although the cuts can vary between long shots and over the shoulder shots, they ensure a consistent screen direction in which viewers can predict where the subjects are with respect to the event.

The axis of action can also be used to establish relationships between two interacting subjects, for example, a speaker and an audience. Cutting between two views on the same side of the 180-degree line establishes a converging index vector that creates the sense that the speaker and the audience are looking at each other. Cutting between views from opposite sides of the line, however, would produce a continuing index vector that make them appear to be looking at a third party. In a motion graphics environment, this principle is illustrated in the music video for the song “Megalomaniac” by the band Incubus. This dark piece, which barrages us with historical live-action footage and animated sequences, makes use of both converging and continuing index vectors to complement the song”s powerful message (8.7; Chapter 2, figure 2.74).

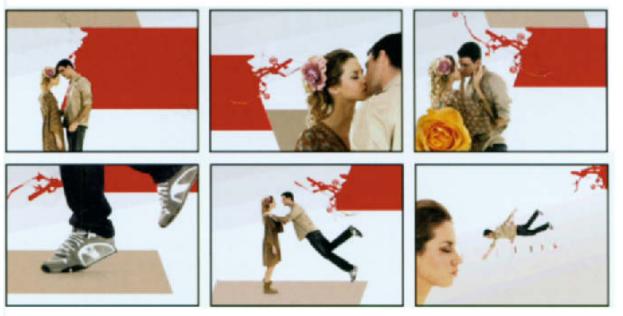

As a general rule, maintaining the positions of major elements in the frame between shots preserves the viewer”s cognitive spatial “map.” Maintaining the directions that elements move from scene to scene also preserves continuity from on screen and off screen space.Figure8.8 illustrates this principle invelvet”s recent design package for Nova Tv, the first Croatian commercial television network. A male figure occupies the right side of the frame, while the female figure is located on the left. Their positioning in the frame is maintained in subsequent views, preserving a sense of spatial continuity. This partially compensates for the abrupt transitions between the shots. A quick cut to a close-up of the male figure”s feet followed by a zoom out and a quick

8.6 Frames from Heritage (Phase 3)by Jon Krasner. 0 Jon Krasner.

360∘ rotation shows the male figure floating away from the woman. Their angle of direction is preserved in the diverging motion vector that is created in his movement.Figure8.9 shows another humorous sequence in which the donkey”s position adheres to the left side of the frame, while the woman”s location remains fixed to the screen”s right half. When we cut to a close-up of the donkey resisting its owner, the motion vector continues toward the right edge of the frame and into the off screen space that we presume the woman occupies.

8.7 Frames from the music video to “Megalomaniac” by Incubus. Courtesy of Stardust Studios.

8.8 Frames from a package redesign for Nova TV, the first Croatian commercial television network. Courtesy of velvet.

Spatial continuity is maintained in the consistent diverging motio vector of the male fiure.![]()

8.9 Frames from a package redesign for Nova TV. Courtesy of velvet.

In this humorous sequence, spatial continuity is maintained in the continuing motion vector between the woman and her donkey.

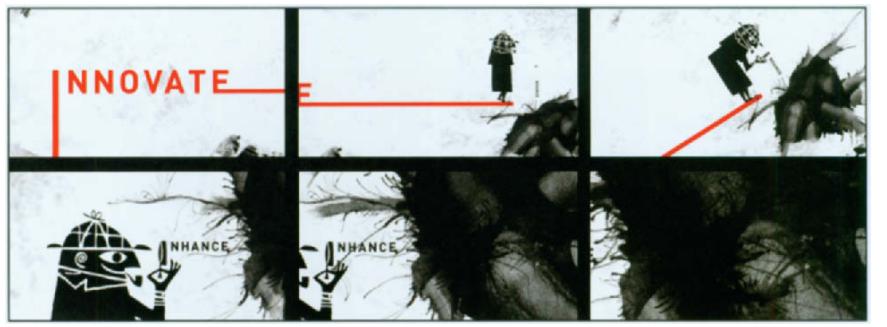

Figure8.10 illustrates a different example of how continuing motion vectors can achieve spatial continuity. The bottom of the uppercase “E” in “innovate” extends outward to the right, leading our eye into the next scene. The view is then zoomed and rotated to feature the detective character. The wide tracking between the letters “NHANCE” points our eye to the right, in concert with the camera”s pan to the next scene.

8.10 Frames from “Adobe.” Courtesy of IAAH

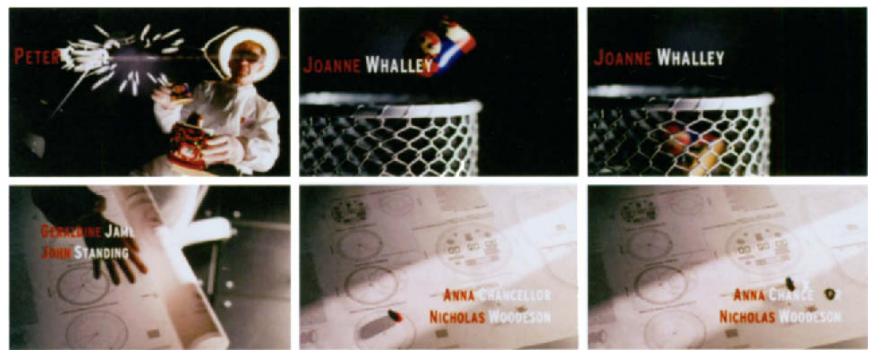

In the Pink Panther-style opening for The Man Who Knew Too Little (1997), a motion vector is established from the character”s flick of an image to the left. After a cut to the next scene, the image”s gravitational motion continues toward the left before bouncing off of the rim of the trash receptacle. The next scene features the character”s hand unrolling a blueprint toward the right-hand edge of the frame. The motion of the image established from the impact of the trashcan enters the frame from the left and continues off the right edge of the screen (8.11).

8.11 hamesfrom the opening titles for The Man Who Knew Too Little (1997). a comic film Starrine Bill Murray. Courtesy of Kemistry.

frame mobility

The effect of mobile framing (or camera motion) on the sequential aspects of a composition can preserve spatial continuity. An example of this is the Web “teaser” for artevo.com ( Chapter 7,figure 7.2). Different scenes are presented through several emulated camera moves A pause or a deceleration between each move is used to emphasize the most important aspects of the concept in words or phrases such as “a global community,” “opportunities,” artists,” and “invest in artists of the world.” In figure 8.12, a single continuous pan is used in an in-store motion graphics sequence for Telecom, maintaining the viewer”s cognitive spatial map.

8.12 Frames from an in-store looped animation for Te,ecom, based on Xtra Broadband”s new communications technologies. Courtesy of Gareth O”Brien of Graffe.

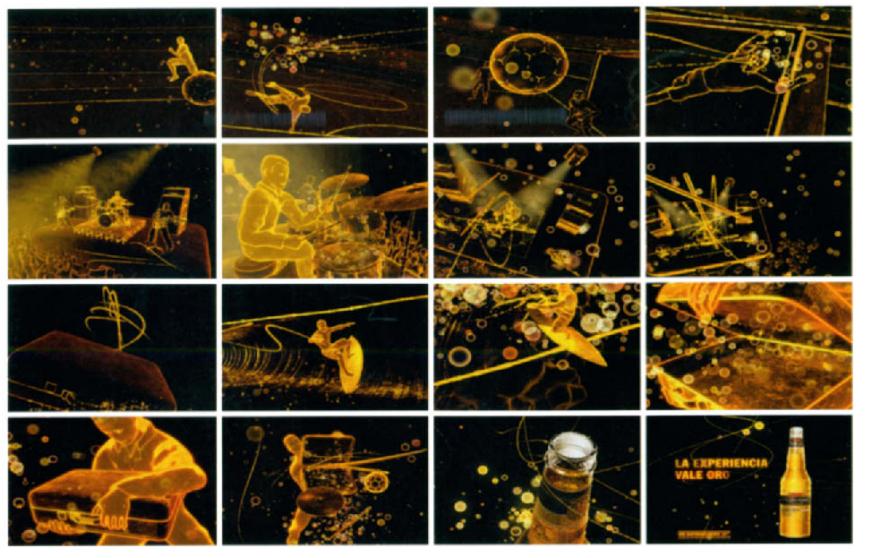

In a TV ad for Miller Genuine Draft, constant camera motion is employed throughout the composition to maintain both spatial and motion spatial continuity between segments (8.13). AS we follow the next scene to observe its continued motion from a different perspective. In another instance, frame mobility gives us a sense of omnipresence as we are shifted in space from a straight on, medium view, to a bird”s-eye view of the drummer. As the frame continues to pull us in an upward direction, the flying drumsticks provide a natural transition into the next scene of a flying suitcase that closes on them in midair. The framing of the last sequence of the composition makes us feel as if we are riding the waves with the surfer.

graphic continuity

Graphic continuity considers the inherent visual properties of line, form, value, color, and texture. For example, instead of employing a fade to link two segments, you might decide to zoom into a shape that matches a shape in the following segment.

8.13 Frames from “Collector.” Courtesy ofThe Ebeling Group.

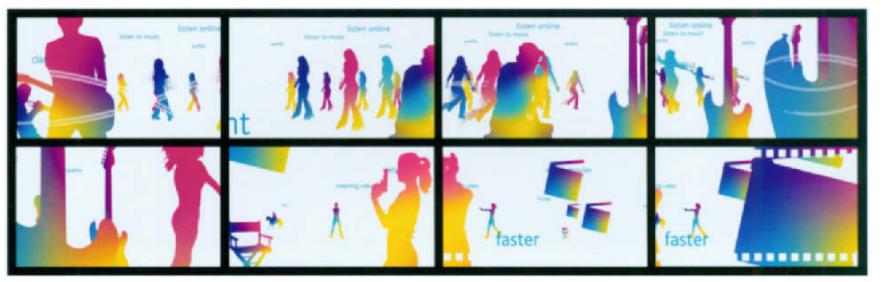

In figure 8.14, the graphical sequences in a trailer for an annual digital film festival Are linked together with straight cuts to match the sonic component of the soundtrack. As similar mechanical structures are repeated, variations of forms, values, colors, textures, and movements maintain our interest. The trailer”s smooth, fluid sense of pictorial continuity feels similar to a piece of well-constructed classical music.

8.14 Frames from a film festival trailer. Courtesy of onedotzero.

Graphic continuity can also function as natural transitions to move you between motion graphic sequences. For example, in Hillman Curtis’ online advertisement for Craig Frasier/Squarepig.tv (Chapter 12. figure 12.17), zooming into a portion of a scene allows us to focus on a simple geometric shape. We then cut to a similar shape and zoom out to show the same event from a different viewpoint. This transitional effect creates a smooth linkage between the two scenes.

temporal continuity

Temporal continuity controls the timing of the action and contributes to a plot classical music.;s manipulation of story time—the way the order of events is presented. Events can be organized in chronological order or, through editing, can alter temporal succession to bring the viewer into the past, present, or future. It can achieve a sense of cause and effect, suspense, or surprise. Classical continuity editing presents sequences of actions in their logical order, and each action is displayed only once. Occasionally flashbacks and flash forwards are used to enhance the viewer classical music.;s awareness of prior events and their relationship to the present. Cutaways are also sometimes used to show related events to the main action. In Strike, Sergio Eisenstein made frequent use of temporal expansion through overlapping shots to prolong the action and reinforce the drama of the event. In October, he combined overlapping shots of rising bridges to demonstrate the event’s impact.

Using dissolves, as opposed to cuts, aids continuity because temporally they act as a time bridge, producing thematic or structural relationships between events. For example, dissolving between a long shot of the wind blowing through several trees, a close-up of leaves blowing on the ground, and wind blowing through a woman’s hair shows a thematic relationship. Dissolving between tree branches blowing in the wind and a woman’s hair blowing in the breeze represents a structural relationship.

Temporal ellipsis can condense small to large quantities of time with the purpose of omitting unnecessary pieces of information that would normally detract the viewer’s attention from the main story. Typical examples of temporal ellipsis during the 1930s and 1940s include spinning newspaper headlines, book pages fluttering, and clock hands dissolving. In Stanley Kubricks film, 2001, the sequence of the bone flying through the air cuts directly to a graphic match of a sequence containing a nuclear weapon in space orbiting the earth. Millennia are

automatically eliminated in less than a second. Many times, dissolves, fades, or wipes are used to indicate temporal ellipsis so that viewers can recognize that time has passed. Brief portions of footage can be linked to compress a lengthy series of actions into a few moments.

action continuity

The actions of animated graphic elements and live-action images can be carried smoothly across cuts and transitions to preserve both spatial and temporal continuity.

The following tips can help preserve action continuity.

1.) Cutting just before or after an action will emphasize the beginning or end of the action, rather than on the flow of the action between sequences. Cutting from a sequence containing a static element to a sequence where the element is in motion will create the effect of the element suddenly accelerating awkwardly through time. On the other hand, if you cut from a sequence that contains a moving element to one where the element is static, the element appears to come to an abrupt halt. Therefore, it is better to avoid the above scenarios and cut during an action to ensure maximum continuity.Figure 8.15 illustrates this principle in a sequence of shots that show different views of a tennis player. Employing cuts during the action preserves continuity

2.) Cutting between different types of actions that move in the same direction will preserve continuity.

3.) When cutting during a camera move, such as a pan or zoom, continue the same motion in the following sequence.

4.) If you are panning with a moving element, continue the pan in the same direction at the same velocity in the following sequence. This will maintain the camera movement through the cut, as opposed to interrupting the cut. Otherwise, there will be a sudden distraction in the flow of movement, and this might appear as a mistake rather than an intentional decision.

8.15 Frames from Flying Machine’s Sci-Fi reel. Courtesy of Flying Machine.

Forms of Disrontinuitv

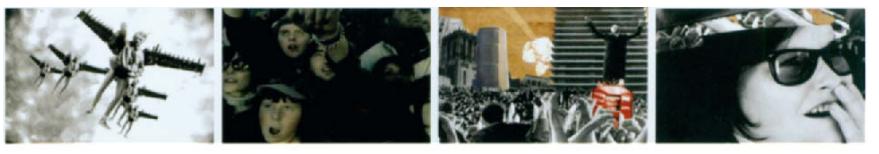

Discontinuity editing offers an alternative approach to editing using techniques that are considered to be unacceptable to traditional continuity principles. Although the classical continuity system has been the most popular historically, violating this system can produce aesthetic effects that may weaken the narrative but intensify its context. In fact, discontinuity editing is guided more by emotion rather than story. It can be used to enhance anticipation or arouse anxiety. David Carson’s music video for Nine Inch Nails, for example, is composed entirely of fleeting, disjointed images that convey the energetic, rebellious nature of the soundtrack. The abandonment of space or time lends itself to what appears to be the band’s underlying themes of rage, self-loathing, and technological hype (Chapter 5, figure 5.19). A montage for the title sequence illustrated in figure 8.16 demonstrates how mismatching spatial and temporal relationships are deliberately used to express the dynamism and power of the Formula 3 race car. In figure 8.17, the motion graphics sequence for Kia Magentis’ Web site also uses discontinuous space and time to establish the mood.

8.16 Frames from a title for Formula 3. Courtesy of Krafthaus Films

narrative and non-narrative forms

Discontinuity has been explored in both narrative and non-narrative forms of cinema and motion graphics. In traditional cinema, narrative alternatives to continuity editing have created unusual ways of telling stories and have become integrated into mainstream culture and practice. Accelerated editing, for instance, has been used to create tension when a story builds to an emotional climax. Crosscutting between simultaneous actions that occur in different locations was considered a radical innovation at the time and is still used frequently today.

8.17 Frames from Kia Magentis’ Web site. Courtesy ofTavo Ponce.

During the 1920s, many European avant-garde painters became the pioneers of avant-garde cinema and have taken the most daring steps in establishing alternatives to continuity editing. Non-narrative forms of discontinuity continue to allow motion graphic designers to focus not on content, but rather on aesthetic form and process.

graphic considerations

A myriad of graphic and rhythmic possibilities exist when you break away from the limitations of spatial, graphic, temporal, and action continuity. Images, actions, and sequences of events can be joined together by virtue of their formal graphic and rhythmic qualities.

In cinema, Bruce Conner’s experimental films, such as Cosmic Ray, A Movie, and Report, for example, joined segments of found newsreel footage, film leader, and old clips with regard to their graphic qualities and patterns of movement.

Many discontinuity practices in early twentieth-century cinema have inspired generations of filmmakers and motion graphic designers in film, broadcast, and interactive motion graphics. David Carson’s intuitive use of kinetic images and typography is similar to his print work, in that it is expressive, experimental, and multilayered. He reinforces content with form, and his use of subtle shape and color contrasts effectively communicates the feel of the subject matter, often eliciting an emotional response from the viewer (8.18).

8.18 Frames from aW commercial for Nike, Courtesy of David

Historical Perspective

Modern art movements, such as German Expressionism, Dada and Surrealism, have employed various form of discontinuity in film to engage audiences on a purely visceral level. Erich Pommer’s German Expressionist film,The Cabinetof Dr. Caligari (1919), wasgroundbreaking in thatitmerged avant–gardetechniques with conventional storytelling. Throughout the film, continuity was often sacrificed to make viewers aware that the irractional convironment depicted a world of insanity that the main character was expericencing.

Surrealist filmmakers after World War I attempted to express dreams and the subconsious by juxtaposing and superimposing ordinary images and events that occur in daily life in unusualcombinations. Their spontaneous and undirected approach to editing allowed themto arrive at far–fetched analogies and bizarre personal fetishes. Many of these films continue to be highly regardedas works of art. Luis bunuel's Belle de jour (1968) provides a voycuristic view into the subconscious mind of a troubled heroine. Salvador Dali's An Andalusian Dog (1928) presents several disturbing events that are intentionally unrclated on a conceptual level. Hans Richter's Ghots Before Breakfast (1927) presents an actor wearing a hat inb one shot, immediately followed by a barcheaded shot of the same actor. Similar typres of changesthroughoutthe film shatter theillusion of graphic and pictorial continuity.

In Russia during the 1920s, Soviet filmmakers, such as Sergel Eisenstein and dziga Vertov, also experimented withspatial and temporal discontinuity with the objective of shocking their audiences out of passive spcetatorship, invitingthem tomakeconceptualconnections between events.

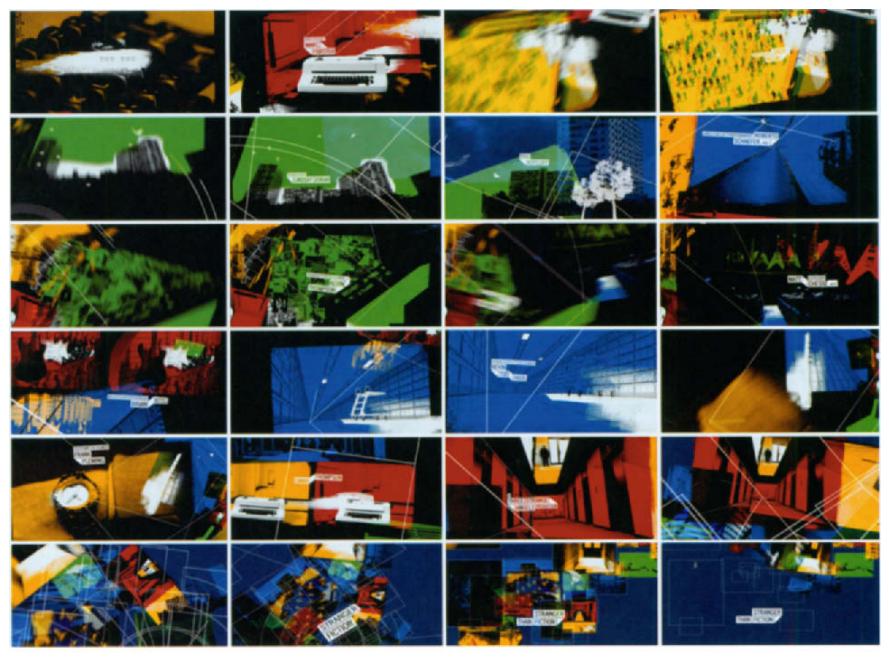

Although narrative can take a back seat when priority is given to visual and conceptual criteria, a composition’s graphic possibilities can help enforce its underlying theme. The ending title sequence to Stranger Than Fiction (2006) is an example of this. The theme of the film depicts how the concept of life can imminently play out like a story. The monotonous existence of an IRS agent hears the voice of an esteemed author inside his head, ominously narrating his life. When the author narrates that he is going to die, he becomes anxiously determined to find her and convince her to change the story. In this credit sequence, quick camera movements and rapid, restless movements of elements entering and leaving the frame completely throw off our sense of space and time. Unrelated spaces and events are shown with different color tints or at unusual angles (sometimes upside down). They appear to occur simultaneously as they are juxtaposed temporally through frame mobility or spatially through superimposition.

Without seeing the film, we see what appears to be a kinetic collage of unrelated images and events. We are forced to appreciate it from a purely formal perspective in terms of its shapes, layering, color, and movement.. After hearing about the film’s concept, it becomes apparent how this stylistic approach enforces the underlying theme. The method in which the composition is sequenced gives us an insight into the world of the author (or of authors in general). When writing a fictional story, authors often pull disparate ideas out of a “hat” and experiment with ways that they could fit together. The disjointed feel of “possibilities” is expressed in the discontinuity of image, time, and space to illustrate the struggle of the author (figure 8.19).

8.19 Stranger Than Fiction. Courtesy of The Ebeling Group. Producer: Keith Bryant; Director: MK 12.

8.20 Frames from Addikt’s promotional film leader, 2007. Courtesy of Addikt.

Discontinuity between sequences of lines and shapes enhances this composition’s aesthetic impact.

subjectivity

The use of subjectivity through point-of-view editing can enhance a story’s narrative structure by representing the viewpoint of one or Frames from Addikt’s promotional film leader, 2007. Courtesy of Addikt. more characters. This approach tends to evolve through developing psychological connections that violate believable space and time that Discontinuity between sequences of lines and shapes enhances this comdositionls aesthetic is inherent to traditional continuity editing.

In Stanley Kubrick’s 2001:A Space Odyssey (1968), the Star-Gate scene representing Keir Dullea’s cosmic journey through time and space is historically one of the most conceptually imaginative sequences in narrative cinema. It confounds our expectations of character point of view by breaking free from the conventions of linear time and space, inviting us to engage in the mysteries of human life and the universe on a deeper level than an average narrative film is capable of.

In motion graphics, many popular film title designs utilize the device of montage to create an emotional environment that allows audiences to connect or identify with the main character. For example, in David Fincher’s crime film, Se7en (1995), Kyle Cooper’s renowned opening credit sequence creates a state of mind, whereby unusual camera

Historical Perspective

After World War I, point–of–view editing allowed French Impressionistfilmmakerstoportray psychologicalstates ofmind. Out–of–focus and filtered shots with awkward camera movements and unusual angles were used to depict the state of mind of drunken or ill characters. They alsoinvented ways of fastening their Cameras to moving vehicles, amusement rides, and machines thatcould move. Experimentation with editing patterns, lenses, makes, and superimpositions allowed acharacter’s inner consiousness to be expressed. The use of flashbacks was also quite common, and sometimes, the majority of the film was a flashback.

In Abel Gance’s romantic melodrama, La Roue (1923), techniques, such as rapid cut montage, extreme and low–angled closeups, tracking, and sup[erimposition establish a rich psychological portrayal of the film’s main character. In the French silent film, La Souriante Madame Beudet (1923), director Germaine Dulac paints his character’s emotional feelings of anxiety, entrapment, and disillusionment through slow motion, distortion, and metaphorical juxtapositions of images (8.21) Scholars and theorists regard this psychological narrative as one of the first “feminist” films. It influenced Hollywood directors, such as Alfred Hitchcock, as well as popular American genres and styles.

angles and manic, unstable movements of typography and live-action elements mimic the psychological nature of a character driven by obsession. The imagery appears as if it “were attacked with razor blades and bleach,” according to an interview with Kyle (“David Fincher: Postmodern Showoff,” by Renee Sutter). In another interview, he stated that somebody told him “I don’t know what that [film] was about, but I felt like I was watching somebody being killed.”

8.21 Frame from Germaine Dulacls La Souriante Madame Beudet (I 922).

In an animated identity for Film4Extreme’s channel launch in the UK, “stylized shots of things that make you squirm” are combined with the themes of “sex, drugs, and tattooing.” Particular portions of the sequence feel similar to the opening titles in Se7en with respect to seeing through the eyes of a character. Abrupt cuts and disjointed, disturbing images of the tattooing process allow us to connect with the bizarre female figure who appears at the very end of the sequence (8.22).

spatial discontinuity

Breaking spatial continuity allows you to reconstruct an environment that partially relies on the imagination of the viewer. This can be used to establish the viewpoint of a character or intensify the emotional impact or mood of the concept.

8.22 Frames from a identity for Film4Extreme. Courtesy of Kemistry.

In Sergio Eisenstein’s film October (19271, a scene of crouching soldiers precedes a shot of a descending cannon. This juxtaposition creates a violation of space, forcing us to depict the figures as if their government was crushing them. A shot of a cannon hitting the ground gives way to an image of starving women and children. Once the wheels hit the ground, we cut to a shot of one woman’s feet in the snow. The repetitive use of cannon imagery makes it difficult to decipher if multiple cannons are being lowered or if one descending cannon is showed several times. Again, we have no choice but to formulate our own interpretation of the event, versus being fed the narrative.

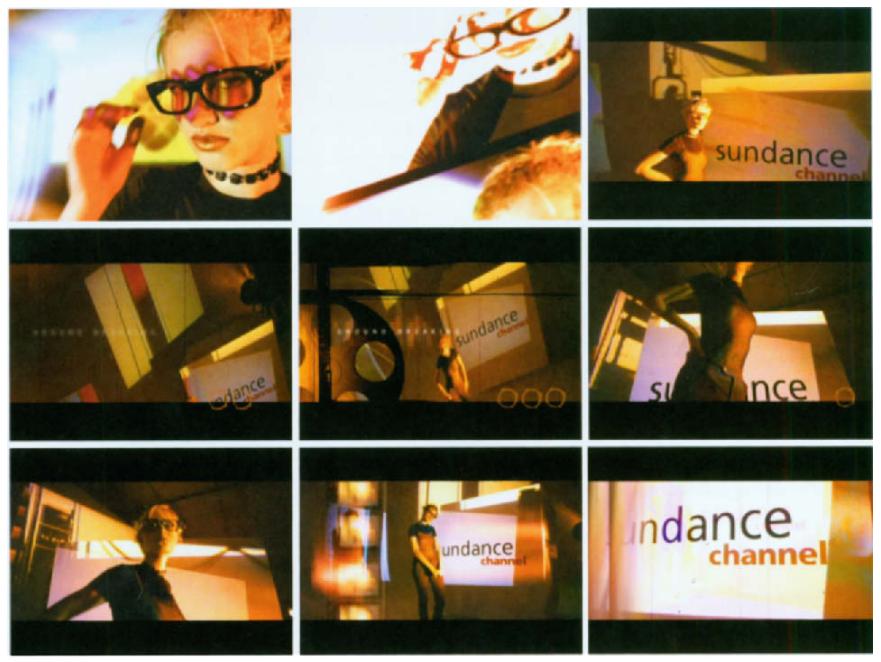

Violating the 180-degree rule can intentionally disorient viewers by throwing off their cognitive spatial map to weaken their impression of an objective world. In Surrealist filmmaking, the 180-degree principle was often abandoned in favor of cutting between opposite sides of a subject’s index vector. This allowed filmmakers to create fantasy worlds that expressed the irrational thoughts of the subconscious mind. The opposing screen directions could effectively portray a character troubled condition’s troubled condition. In figure 8.23, this strategy adds visual interest to a scene that might otherwise have been too predictable if edited in traditional Hollywood-style. Giant Octopus’ promotional interstitial for the Sundance film channel, which portrays a female figure posing next to a movie screen with the channel’s identity projected onto it, commences with a medium-close-up shot of the figure seductively pulling her glasses downward. This subtle motion is accompanied by an abrupt frame stutter effect that lasts for a few frames. An abrupt shift to a long shot and a zoom in to the figure gives us a cognitive spatial map of the

environment. Our logical sense of the space is, however, interrupted as another frame stutter is followed by a bird’s-eye view of the scene. A rotating film reel occupies the foreground plane, and a line of type moves across the frame. Another cut reveals a camera tilt upward from the figure’s waist to her face. This motion is intercepted by another long shot in which an animated filmstrip plays next to the figure in the foreground. A cut to a close-up of the projected channel identity is followed by a final long shot that shows the movie screen from a side angle. The varied frame duration between these scenes contributes to the composition’s overall sense of discontinuity.

8.23 Sundance film channel. Courtesy of Giant Octopus.

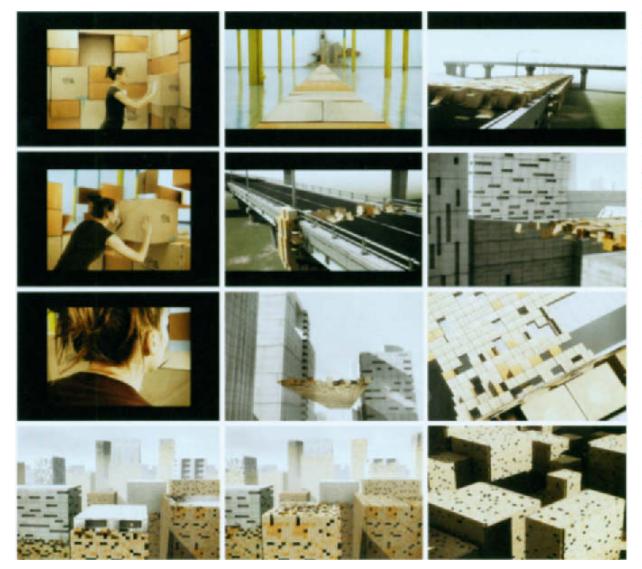

In Velvet’s package for the political evening program for the Franco German culture arte, the theme of political entanglement, symbolized by a labyrinth and a ball of yarn, is expressed through the spatial discontinuity between the shots. The backdrop of the labyrinth, similar to an Escher drawing in which space defies the laws of physics, reinforces this concept. Throughout the composition, spatial discontinuity is maintained by mixing camera angles in coordination with the chaotic body and hand movements of the actors (Chapter 5, figure 5.18). In contrast, the re-branding of a German children’s television program in figure 8.24 illustrates how spatial discontinuity between scenes is used to express the feeling of haphazard, spontaneous play. The goal of the package was to appeal to children between the ages of 3–14 years.

8.24 Frames from the re-branding of ZDF-TIVI, a German national television program for children. Courtesy of velvet.

temporal discontinuity

Breaking temporal continuity also allows you to deliberately create ambiguity, build tension, and intensify emotional impact.

Sergio Eisenstein conceived of film as a vehicle for experimental editing, and he aimed to alter the viewer’s consciousness by refusing to present a story’s events in their correct, logical order. Likewise, Hans Richter strove to alter our sense of chronological time in his Ghosts

Before Breakfast (1927). Mismatched cuts and unexpected transitions present shots of men with and without beards, creating the effect that their beards magically appear and disappear in the frame. Teacups’ fill by themselves, hats fly around, and a man’s head detaches itself and floats in the air. At times, characters even move in reverse.

jump cuts and flash cuts

In classical continuity-style editing, jump cuts and flash cuts (Chapter 12) are considered technical flaws, because they violate temporal continuity. However, they have become part of today’s cinematic vocabulary because of their ability to show an ellipsis of time, arouse tension, or create disorientation by breaking the flow of events. For example, the promos for Chappelle’s Show employ jump cuts to illustrate the sharp, defiant humor of the series (Chapter 12, figure 8.25).

8.25 Frames from “Melting Point,” a fictional television show opening by Corey Hankey, Rochester Institute of Technology, Professor Jason Arena.

Jump cuts are used with choppy camera movements and abrupt transitions to create the hip atmosphere of a realty TV show.

The captivating opening titles to the Fear Makers film, Death 4 Told (2004) combines jump cuts and flash cuts to provide an insight into the mind of a voyeur whose presence is only suggested. Viewers are induced with fear and anxiety as they witness startling evidence of the character’s madness from a trail of items that he has obsessively collected. In one particular segment, a pan of a brick wall containing various crime scene paraphernalia is followed by a flash cut to the dark face of a woman emerging from the background as the first credits begin to appear. Another cut presents an eerie image of a doll’s face that connects us to one of the piece’s vignettes, “The Doll’s House” (8.26).

8.26 Frames from the opening titles for Death 4 Told (2004). Courtesy of Steel coast Creative.![]()

8.27 Frames from Box, a Surrealist film. Directed by the Toronto based company Nakd. Courtesy of The Ebeling Group. Executive Producer: Mick Ebeling; Producer: Susan Lee.

Jump cuts between camera angles, distances, and movements of the figure to create a sense of drama and urgency.

8.28 In an identity for Domes tika, a community that fosters sharing artistic disciplines, jump cuts and frame stutters were choreographed to match the rap-like beat of the soundtrack. Courtesy of Tavo Ponce.

parallel editing

Parallel editing is a common way to explore discontinuous spatial and temporal possibilities. Achieved through the technique of crosscutting, it can be used to create the illusion that different events are interwoven in time or in space. D. W. Griffiths film Intolerance (19161, for example, interweaves events from different eras and distant countries based on their logical (versus spatial or temporal) relationships. At one point, he cut from a setting in ancient Babylon to Gethsemane, and from France in 1772 to America in 1916. In Schindler’s List (1993), director Steven Spielberg used parallel editing to contrast between the hardships of the Jews with the comfortable lifestyle of Schindler and the Nazis.

In motion graphics, music videos have used crosscutting to create impossible worlds in which a character magically appears in different sets or locations “at the same time.” In a television commercial promoting Bombay Sapphire’s gin, Stardust Studios presented various women, all who represent a heroine, walking through environments, while pieces of the environment attach to them. The use of parallel editing allows the heroine to be transported between different worlds, from a grim, black and white cityscape into an exotic dream, lush with vegetation and wildlife. After diving into a body of water and swimming with a school of translucent jellyfish, she appears to be free and revived and is again transported into a newly transformed sapphire-blue city to make her way home in the evening’s clear moonlight (8.29).

In a public awareness advertisement for Japan Railways, parallel editing was used to create a dual existence between a young musical performer who passionately plays the violin and a group of kindergarteners. In a second ad, shots of the performer are crosscut with shots of a service manager in a subway station directing commuters to their destinations (8.30).

8.29 Frames from“Step into Blue;” a television commercial to promote Bombay Sapphire. Courtesy of Stardust Studios.

8.30 Frames from “Service Manager” and “Kindergarten,” ads from a public awareness campaign for Japan Railways. Courtesy of The Ebeling Group. Executive Producer: Mick Ebeling; Producer Susan Lee: Director: Nakd.

event duration and repetition

Controlling the “life” of on screen events allows you to differentiate actual story time from screen time (or storytelling time). You can take liberties with the duration of events; events can be stretched out to make screen time greater than story time, or they can be consolidated in order to emphasize the principal actions. For example, an event that would normally consume five hours could be reduced down to a few minutes or seconds to deliver the main point. Additionally, events can be repeated, and each repetition can be shown from different camera angles, spatial distances, and heights, as well as at a different speed or frame duration.

In a television segment for Times Now, a cable network based in India, the movement of the graphic flying toward the camera is repeated five times, each time with a slightly different speed and a different angle and positioning in the frame. This break with temporal continuity effectively conveys a sense of urgency that depicts the fast pace of the

broadcast news industry (8.31). In a bumper for the Golf Channel cable network, the action of a live-action figure swinging a golf club is repeated in tiny silhouettes that are juxtaposed in the lower portioi of the frame. Their similar, repeated motions alter our perception of time to emphasize the swing (8.32).

8.31 Frames from 6 Minutes, a segment fromTimes NOW, a cable network based in India. Courtesy of Giant Octopus.

Montage

During the aftermath of Word War I, painters and filmmakers became liberated to explore new ways of presenting ideas through the technique of montage. Surrealist and Dada filmmakers began juxtaposing unusual combinations of mundane images of daily life events to explore dreams and the subconscious. Their spontaneous, playful approach to editing, in contrast to Hollywood’s traditional continuity style, allowed them to create far-fetched analogies and bizarre personal fetishes. In Salvador Dali’s An Andalusian Dog (1928), the main character drags two pianos filled with dead donkeys across a room. In a disturbing scene at the beginning of the film, a man slits the eyeball of a woman with a razor blade, and her reaction is lifeless and apathetic. Hans Richter’s Ghosts Before Breakfast introduces obscurity and fantasy by incorporating clocks, hats, ladders, and figures into unusual, irrational settings.

8.32 Frames from a bumper for the Golf Channel. Courtesy of Gian octopus.

conceptual forms

Conceptual montage (also referred to as idea-associative montage) involves juxtaposing two different ideas to formulate a third concept or tertium quid. This allows you to communicate complex messages to an audience in a short period of time.

One form of conceptual montage is the comparison montage, which involves juxtaposing two thematically similar events to reinforce a basic idea. For example, an image of a lighted cigarette on the ground followed by an image of a burning forest conveys the idea of environmental awareness. The collision montage involves juxtaposing two thematically unrelated events. The resulting idea is the result of the dualistic conflict between the two original ideas.

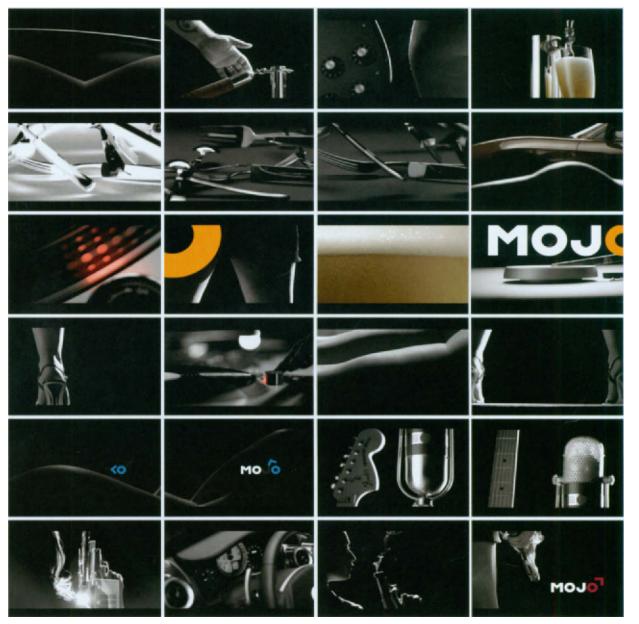

Flying Machine’s design package for MOJO, a high-definition, maleoriented entertainment network, demonstrates a combination of comparison and collision montage. The goal was to create an edgy, suggestive design that had “attitude.” Many of the themes, ranging from beer and cooking to exotic cars, exotic women, music, and travel adventure, allowed creative director Micha Riss to take many liberties in comparing and contrasting images. For example, a shot of twisting and turning kitchen utensils precedes a slow pan of a sensuous female torso in the foreground and the sleek body of a car in the background. The juxtaposition between human and machine, or organic and synthetic, challenges us to make a connection. Another segment featuring extreme close-up shots of a guitar neck and a microphone moving in opposite vertical directions also invites us to construct a tertium quid through comparison and contrast. The composition ends with a medium shot of a female figure erotically extinguishing the barrel of a smoking gun with her lips (8.34).

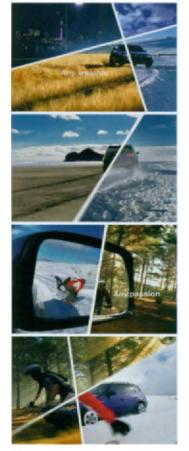

8.33 This commercial for BMW employs an animated Screen to tie together various driving conditions governed by weather and terrain. Courtesy of Stardust Studios.

Sergio Eisenstein discovered that if a film was edited to synchronize with the human heartbeat, it could have a tremendous psychological effect on his audiences. In his essay “A Dialectic Approach to Film Form,” he compares conflict in history to editing in film. In Strike! (1924), he juxtaposes a workers’ rebellion being put down with a nondiegetic insert of cattle being slaughtered. Eisenstein’s use of parallel editing synthesizes two ideas to produce a third idea symbolizing that the workers are cattle. In the “Odessa Steps” sequence of Battleship Potempkin (1925), Eisenstein juxtaposed images Of innocence against images of violence. He also mixed contrasting long shots and low

8.34 Frames from a network package for MOJO, a male-oriented, highdefinition TV channel featuring a block of original prime-time shows.Courtesy of Flying Machine.

angle shots of the soldiers with close-ups of the citizens to depict their fear and panic. In October, Eisenstein forces us to actively interpret the events by confronting us with disoriented sequences of images of the protagonist-the Russian people-the antagonist-the Provisional Government-that continued to support its allies after the Revolution. Shots of soldiers socializing with their German enemies are followed by a shot of a bombardment in which they run to their trenches.

Another scene of the soldiers on the battlefield follows a shot of a cannon being lowered from an assembly line. Shots of a tank are crosscut with those of hungry women and children standing in breadlines in the snow. As a result, the delineation of narrative is sacrificed in favor of a rhythmically striking composition that invites us to connect with the theme emotionally. Many music videos since the late 1980s have continued to employ Eisenstein’s theories of montage.

analytical forms

Analytical forms of montage can be used to indicate a passage of time and condense or expand time within a narrative context. It can also be used to synthesize different time zones of one or more related events into a single event. Although the content is critical and is considered in terms of its thematic attributes, analytical montages often violate continuity in order to focus on the emotional aspects of the subject matter.

The early cinematic technique of sequential montage (also referred to as cause-and-effect montage or narrative montage) has been used to tell stories in shorthand by condensing events down into their primary components and presenting them in their original cause-and-effect

Historical pespective

In early avant-garde filmmaking, sequential montage often involved deconstructing the content by cutting up the film and editing it back into a condensed series of events. It often relied on devices, such as repetition, close-ups, rapid cuts, and dissolves, to eapture and hold the audience’s attention. Walter Ruttman’s Berlin: Symphony of a Big City (1927) is an extraordinary documentary that provides an intimate model of urbanization by juxtaposing sequences of images of horses, trains, bussling crowds, and machines to express the dynamism of Berlin. Associations berween the everday lifestyle of the working class and that of the wealthy clite suggest a basic similarity, versus a class struggle. The linking of these sccnes unifies the content of the film by showing a cross scetion of a city in motion, the interaction of its parts contributing to the whole.

In Russia, Sergel Elsenstein and Dziga Vertov utilized sequential montage to express ideas about popular culture. Influenced by the Soviet avant-garde, Eisenstein rejected conventional documentaries that involved linking scenes in a smooth, logical manner. His films made complex, visual statements by shocking his audiences with totally unexpected scenes that were composed of numerous different shots.

order. Although the presentation is linear, spatial continuity rules are often broken to emphasize the story’s highlights and shift viewers through time to suggest a fleeting passage of events.

In Krafthaus Films’ opener for a New Zealand music video competition, sequential montage was employed to showcase “the ultimate sexy rock chick” in “a virtual world where she moves from heavy rock hardware into a more Zen-like space after her climax,” according to David Stubbs, the producer, writer, and director for the video (8.35). In figure 8.36 an animation based on the Greek legend of Icarus is consolidated into a sequential montage that lasts a little over a minute.

8.35 8.35 Frames from the opening titles for a New Zealand music video competition. Produced, written, and directed by David Stubbs and Gareth O’Brien for Radio Active 89FM. Courtesy of Krafthaus Films.

Sequential montages usually do not show the main event; rather, they imply it. This forces viewers to participate in the story by making their own personal connections. A boxing sequence, for example, may begin with a medium shot of one player gearing up to throw a punch. We then cut to a bird’s-eye view of both players during the action of the punch. A shot of the crowd immediately follows, and then we cut to a final close-up of the second player down on the ground. The action

8.36 Frames from “lcarus.” © 2005 Adam Scwaab

of the second player receiving the punch is never actually shown. We are also forced to decipher space and time as continuous, even though continuity rules are broken. In a simple motion graphics scenario, a shot of an object moving across the screen is followed by a shot of another object crossing its path. These are the cause aspects of the montage. The next shot reveals the object’s effect after the impact. The actual event in which they interact is only implied. We are expected to apply closure to realize the full event, rather than being hand-fed all aspects of the story. Although time has been condensed to intensify the emotional feel, the original order of events has been preserved.

In a Sundance Film Festival bumper, Digital Kitchen conceived the idea of using pop-up imagery from children’s books.Their animated version of Icarus begins with a long shot of the main character poised on a balcony. An abrupt cut reveals a close-up of his legs standing at the edge and then leaving the balcony to propel him on his journey toward the sun. After a quick cut to a circular, radiating image of the sun (a desk lamp), the sequence ends with a scene of feathers floating down behind the main title to the bottom of the frame. Instead of experiencing the entire event, we are treated to its aftermath (8.37).

8.37 Frames from an animated bumper for the Sundance Film Festival 2006. Courtesy of Digital Kitchen.

Unlike the sequential montage, the sectional montage interrupts the flow of time by bringing the progression of the story’s events to a halt in order to focus on an isolated action or event. Events are not presented in their original cause-and-effect sequence, but rather, in a nonlinear fashion, allowing us to construct a unique, new meaning, apart from the larger context they belong to. Herbert Zettl offers a terrific analogy in his book, Sound, Sight, Motion: “The sectional montage acts more like a musical chord in which the three notes compose a gestalt that is quite different from playing them one by one.”

As an alternative to cutting, events can be juxtaposed pictorially in the form of a split screen display or as a presentation across multiple screens to show them happening concurrently. Sports telecasts and news presentations often rely on the divided screen to reveal specific moments from various points of view. Modern day television dramas, such as 24, make effective use of split-screen sectional montage to illustrate simultaneous events occurring in different locations.

Summary

Sequential composition considers the manner in which events occur over time. Cinematic language and traditional editing techniques can be used to tell stories in meaningful ways.

Continuity editing practices have been used to create a logical sense of space and time. The use of index and motion vectors can preserve the viewer’s logical sense of space between scenes.Graphic and temporal continuity can be used to create smooth linkages between scenes and

to contribute toward a plot’s manipulation of story time. The device of temporal ellipsis can condense time in order to omit unnecessary information that might detract an audience’s attention from the story.

Discontinuity can be used to enhance anticipation or arouse anxiety. The use of subjectivity through point-of-view editing can enhance a story’s narrative structure by representing the viewpoint of one or more characters. Breaking spatial continuity can reconstruct an environment that partially relies on the imagination of the viewer. Varying event duration and repetition allows you to break temporal continuity in order to differentiate actual story time from screen time. Events can be stretched out, consolidated, or repeated from various viewpoints.

The technique of montage can be used to help audiences connect or identify with the subject matter.Conceptual montage involves juxtaposing two different ideas to formulate a third idea or tertium quid.Sequential montage tells stories in shorthand by condensing events into their primary components in their original cause-and-effect order. The main event is typically implied, forcing viewers to make their own personal connections. The sectional montage interrupts the flow of time by bringing the story’s events to a halt in order to focus on an isolated action or event.

Assigments

The following assignments are intended to help you strengthen your sensitivity to the sequential aspects of a composition. Share your work with others and discuss what devices (i.e., motion vectors, frame mobility, event duration and repetition, subjectivity, etc.) were used to create continuity or discontinuity. Consider what aspects of these projects could potentially be applied to “real world” assignments.

spatial continuity: primary motion # 1

overview

You will construct and edit three animated sequences of a moving object shown from multiple viewpoints.

objective

To explore how continuity editing can create a logical interpretation of a space shown from multiple perspectives.

Nest these three compositions into a fifth 10-second composition, and vary their in and out points to show only a portion of each. Edit them together using straight cuts.

specifications

You are to stay within the 10-second time limit. For this reason, you are to use only straight cuts, since transitions occupy time.

considerations

To establish spatial continuity in the scenario of two people having a conversation or engaging in a game or physical activity, all cameras are placed on one side of a 180-degree line. The same principle should be applied to this assignment; consider using an imaginary axis of action to determine the correct camera viewpoints. Additionally, consider how spatial continuity can be preserved from on screen into off screen space by maintaining the direction that elements move between scenes

spatial continuity: secondary motion # 1

overview

You will construct and edit a series of animations that show an object from multiple camera angles, spatial distances, and frame mobility.

objective

To explore how continuity editing can be used to create a logical interpretation of an object in a space shown from various perspectives and mobile framings.

stages

Create a simple shape or letter form in a three-dimensional space using a program that has 3D capabilities.

Create five 10-second compositions, each containing the static shape or letter form. Incorporate a camera into each composition, and adjust its position and settings to reveal a different perspective of the element. Next, animate the camera in each to create a different type of mobile framing. (One composition might show a zoom in from a bird's eye view, while another might employ a tilt upward from a frontal, close-up view.)

Nest these animations into a new 10-second composition, and vary their in and out points to show only a portion of each. Edit them together using straight cuts.

Nest these animations into a new 10-second composition, and vary their in and out points to show only a portion of each. Edit them together using straight cuts.

- In most of these assignments. cutting during the element’s motion (instod of before or after it) will ensure maximum continuity.

- Movements should only be presented once their logical order to preserve continuity.

- Establishing a spatial context that shows the entire subject at some point during the piece will help maximiae spatial continuity.

- When cutting during a camera move, contiue the same move in the following segment through the cut, versus intercepting the cut. for example. if you are pannin form a particular camera angle or disance, contiue the pan in the some direction in a subsequent sequence that might prseent the subject from a different angle or distance. Try to match the speed of the consecutive moves to maintain the flow of movement.

specifications

You are to stay within the 10-second time limit. For this reason, you are to use only straight cuts, since transitions occupy time.

considerations

To establish spatial continuity in the scenario of two people having a conversation or engaging in a game or physical activity, all cameras are placed on one side of a 180-degree line. The same principle should be applied to this assignment; consider using an imaginary axis of action to determine the correct camera viewpoints. Additionally, consider how spatial continuity can be preserved from on screen into off screen space by maintaining the direction that elements move between scenes

spatial continuity: secondary motion # 1

overview

You will construct and edit a series of animations that show an object from multiple camera angles, spatial distances, and frame mobility.

objective

To explore how continuity editing can be used to create a logical interpretation of an object in a space shown from various perspectives and mobile framing.

stages

Create a simple shape or letter form in a three-dimensional space using a program that has 3D capabilities.

Create five 10-second compositions, each containing the static shape or letter form. Incorporate a camera into each composition, and adjust its position and settings to reveal a different perspective of the element. Next, animate the camera in each to create a different type of mobile framing. (One composition might show a zoom in from a bird’s eye view, while another might employ a tilt upward from a frontal, close-up view.)

Nest these animations into a new 10-second composition, and vary their in and out points to show only a portion of each. Edit them together using straight cuts.

specifications

You are to stay within the 10-second time limit. For this reason, you are to use only straight cuts, since transitions occupy time.

consideration

Consider how the effect of frame mobility preserves spatial continuity. Consider employing the 180-degree rule. Placing all cameras on one side of an imaginary axis of action will help maintain spatial continuity.

primary and secondary motion # 1

overview

You will construct a live-action sequence of two figures interacting based on a series of shots that show multiple camera angles, spatial distances, and mobile framings.

objective

To explore how continuity editing can create a logical interpretation of an event that is shown from various perspectives and mobile framings.

stages

Choreograph a 10-second performance of two people interacting in a conversation, a game, or physical activity. Since they will be performing the activity several times, have them rehearse the motions so that they are consistent.

Videotape the event five times, each from a different camera angle and distance. Frame mobility can be employed during shooting or on the computer after the footage has been digitized. Each clip should be approximately 10 seconds long.

Digitize and import the clips into a motion graphics application of your choice. Vary the in and out points of each clip to show only a portion of each. Edit them together using straight cuts.

specifications

You are to stay within the 10-second time limit. For this reason, you are to use only straight cuts, since transitions occupy time.

considerations

Consider how frame mobility preserves spatial continuity. Consider employing the 180-degree rule. Placing all cameras on one side of an imaginary axis of action will help maintain spatial continuity.

primary and secondary motion # 2

overview

You will record and edit a live-action scene from multiple camera angles, spatial distances, and mobile framings of the event.

objective

To explore how continuity editing can create a logical interpretation of an event that is shown from various perspectives and mobile framings.

stages

With the help of three people, film a short live-action sequence from four different camera angles and spatial distances. Frame mobility can be employed during shooting or created digitally after the footage has been digitized. Each clip should be approximately 10 seconds long.

Digitize and import the clips into a motion graphics application. Vary their in and out points, and edit them together using straight cuts.

specifications

You are to stay within the 10-second time limit. For this reason, you are to use only straight cuts, since transitions occupy time.

considerations

Consider how frame mobility and the 180-degree rule preserves spatial continuity.

breaking spatial continuity

overview

You will reconstruct assignments 1–4 to break spatial continuity.

objective

To investigate how violating continuity can deliberately disorient theviewer in order to arouse mystery or induce emotions.

specifications

You are allowed to duplicate object and camera movements and present them out of their original sequence. Use only straight cuts in order to stay within the 10-second time limit.

considerations

Observe how deviating from the 180-degree rule and cutting before or after object or camera actions makes space discontinuous.