13. Saving and Printing Images

Photoshop Elements can save images in a number of file formats, each with its own set of specialized uses and limitations. In this chapter, I’ll begin with a discussion of formatting options and then move on to other considerations for saving your image files and preparing them for printing. I’ll look at how to format and save multiple images (known as batch processing) and then look at tools you can use to lay out, organize, and catalog your image files. In addition, I’ll look closely at the steps necessary to get the best prints from your digital images, whether you’re printing them at home or uploading your files to an online photo service.

Understanding File Formats

Photoshop Elements lets you save an image in many different file formats, from the native, information-rich Photoshop format to optimized formats for the Web, such as GIF and JPEG. Among these is an extremely specialized collection of formats (PCX, PICT Resource, Pixar, PNG, Raw, Scitex CT, and Targa) you’ll rarely need to use and won’t be discussed here. What follows are descriptions of the most common file formats.

Photoshop

Photoshop (PSD) is the native file format of Photoshop Elements, meaning that the saved file will include information for any and all of Elements’ features, including layers, styles, effects, typography, and filters. As its name implies, any file saved in the PSD format can be opened not only in Photoshop Elements, but also in Adobe Photoshop. Conversely, any Photoshop file saved in its native format can be opened in Photoshop Elements. However, Photoshop Elements doesn’t support all the features available in Photoshop, so although you can open any file saved in the PSD format, some of Photoshop’s more advanced features (such as layer sets) won’t be accessible to you within Photoshop Elements.

A good approach is to save every photo you’re working on in the native Photoshop format and then, when you’ve finished editing, save a copy in whatever format is appropriate for that image’s intended use or destination. That way, you always have the original, full-featured image file to return to if you want to make changes or just save in a different format.

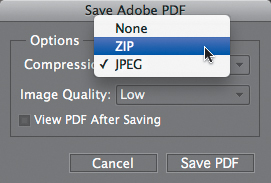

Figure 13.1 When you save your work as a PDF file, you can apply JPEG or ZIP compression.

JPEG and GIF

The two major Web file formats (JPEG and GIF) are covered in detail in Chapter 12, “Preparing Images for the Web,” so I’ll look at them just briefly here. Of particular note is the fact that you can use the Save As command to save an image as a GIF or JPEG file, with virtually all of the same file options as in the Save for Web dialog—so the obvious question is: Why use one saving method over the other when saving for the Web?

The Save for Web dialog offers several features the individual GIF and JPEG Save As command dialogs don’t. For one, Save for Web provides a wonderful before-and-after preview area.

No less valuable is the flexibility you have to change and view different optimization formats on the fly. An image just doesn’t appear the way you expected in GIF? Try JPEG. Additionally, with the click of a button, you can open and preview your optimized image in any browser present on your system.

Photoshop PDF

Portable Document Format (PDF) is the perfect vehicle for sharing images across platforms or for importing them into a variety of graphics and page layout programs. PDF is also one of only three file formats (native Photoshop and TIFF are the other two) that support an image file’s layers; layer qualities (like transparency) are preserved when you place a PDF into another application like Adobe Illustrator or InDesign. The real beauty of this file format is that any document saved as a PDF file can be opened and viewed by anyone using Adobe’s free Acrobat Reader software, which Adobe bundles with its applications and makes available as a free download from its Web site. PDF offers two compression schemes for controlling file size: ZIP and JPEG (Figure 13.1).

TIFF

Tagged Image File Format (TIFF) is a workhorse among the file formats. The format was designed to be platform independent, so TIFF files display and print equally well from both Windows and Macintosh machines. Additionally, any TIFF file created on one platform can be transferred to the other and placed in almost any graphics or page layout program.

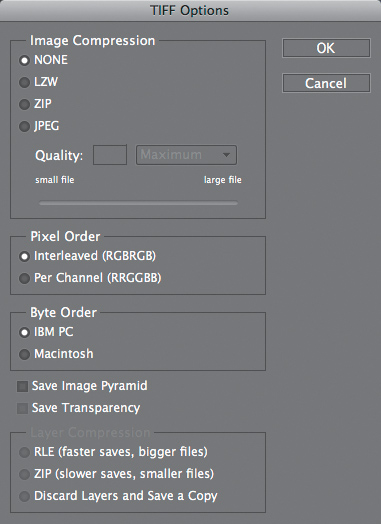

You can optimize TIFF files to save room on your hard drive using one of three compression schemes, or you can save them with no compression at all (Figure 13.2). Of the three compression options, LZW is the one supported by the largest number of applications and programs.

The Pixel Order option should be left at the default of Interleaved. The Byte Order option encodes information in the file to determine whether it will be used on a Windows or Macintosh platform. On rare occasions, TIFF files saved with the Macintosh option don’t transfer cleanly to Windows machines. But since the Mac has no problem with files saved with the IBM PC byte order, I recommend you stick with this option.

Checking the Save Image Pyramid check box saves your image in different tiers of resolution, but since not many applications support the Image Pyramid format, leave this box unchecked.

Checking the Save Transparency check box ensures transparency will be maintained if you place your image into another application like Illustrator or InDesign.

If your image contains layers, you can choose from two Layer Compression schemes, or choose to discard the layers altogether and save a copy of your image file.

Figure 13.2 Although the TIFF format offers several compression schemes, LZW is usually the most reliable.

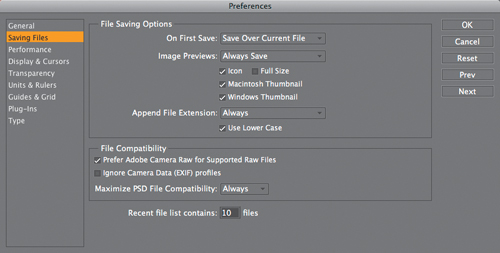

Figure 13.3 The Saving Files window of the Preferences dialog.

Figure 13.4 The On First Save drop-down menu lets you control when the Save As dialog appears.

Figure 13.5 Use the File Extension drop-down menu to determine whether you want filename extensions displayed.

Setting Preferences for Saving Files

The Saving Files portion of the Preferences dialog provides a number of ways to control how Elements manages your saved files.

To set the Saving Files preferences:

1. From the Photoshop Elements menu, choose Preferences > Saving Files. The Preferences dialog opens with the Saving Files window active (Figure 13.3).

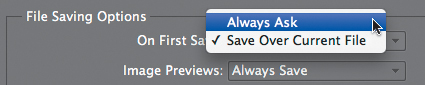

2. From the On First Save drop-down menu, you can choose when you want to be prompted with the Save As dialog (Figure 13.4).

3. From the Image Previews drop-down menu, choose an option to either save or not save a preview with the file.

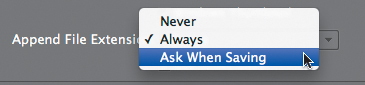

4. From the Append File Extension dropdown menu, choose whether file extensions should or should not be added (Figure 13.5).

5. In the File Compatibility portion of the dialog, set the Maximize PSD File Compatibility drop-down menu to Always. This gives you the maximum number of compatibility options.

6. If you’re pre-processing Raw files in another program, deselect the Prefer Adobe Camera Raw for Supported Raw Files option.

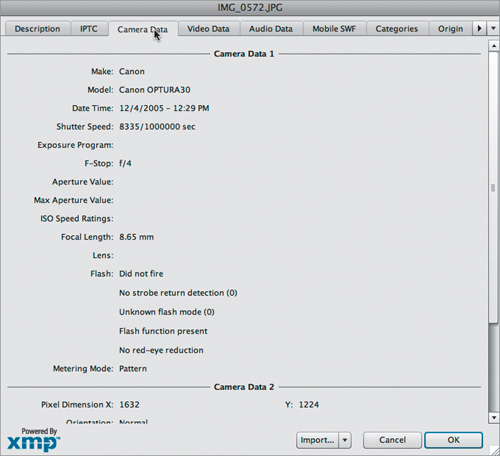

7. Digital cameras assign their own color profiles (EXIF profiles) to your digital photos. If you’d prefer to assign your own profiles in Elements, select the Ignore Camera Data (EXIF) profiles check box.

8. In the text box labeled Recent file list contains, enter a number from 1 to 30.

9. Click OK to close the dialog and apply your preferences settings.

Figure 13.9 You can save groups of files from a number of different sources.

Figure 13.10 Select a folder containing all the images you want to save at one time.

Formatting and Saving Multiple Images

You’ve just finished a prolific day of shooting pictures, and as a first step to sorting through all those images, you’d like to convert them to Elements’ native Photoshop format and then change their resolution to 150 dpi. You could, of course, convert them individually, but the Process Multiple Files command can do all that tedious, repetitive work for you.

To batch process multiple files:

1. From the File menu, choose Process Multiple Files to open the dialog of the same name.

2. From the Process Files From dropdown menu (Figure 13.9), do one of the following:

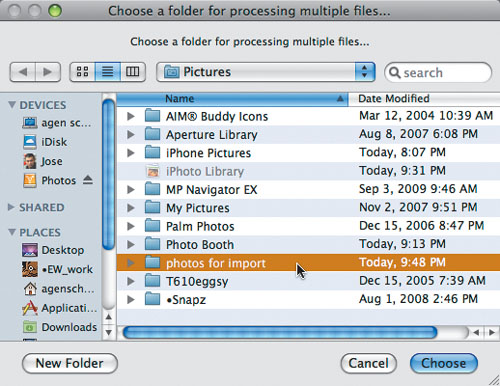

![]() To select images within a folder on your hard drive, choose Folder, click the Browse button, and then locate and select the folder containing the images you want to convert (Figure 13.10). If you spot folders within the folder you select that also contain files you want to convert, click the Include All Subfolders check box in the Process Multiple Files dialog.

To select images within a folder on your hard drive, choose Folder, click the Browse button, and then locate and select the folder containing the images you want to convert (Figure 13.10). If you spot folders within the folder you select that also contain files you want to convert, click the Include All Subfolders check box in the Process Multiple Files dialog.

![]() To select images stored in a digital camera, scanner, or PDF, choose Import; then select the appropriate source from the From drop-down menu. The choices in the From dropdown menu will vary depending on the hardware connected to your computer.

To select images stored in a digital camera, scanner, or PDF, choose Import; then select the appropriate source from the From drop-down menu. The choices in the From dropdown menu will vary depending on the hardware connected to your computer.

![]() To select files that are currently open within Photoshop Elements, choose Opened Files.

To select files that are currently open within Photoshop Elements, choose Opened Files.

3. Click the Destination Browse button; then locate and select a folder to save your converted files.

In the Browse for Folder dialog that appears, you’re also offered the option of creating a new folder for your converted files.

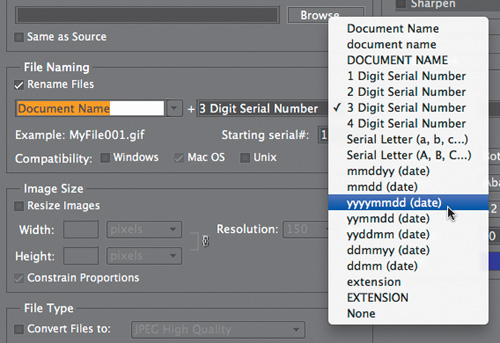

4. If you want to add a file naming structure to your collection of converted images, select the Rename Files check box; then select naming options from the two dropdown menus (Figure 13.11).

Refer to the Example text (located below the Rename Files check box) to see how the renaming changes will affect your filenames.

5. Select the Compatibility check boxes for whichever platforms you want your filenames to be compatible with.

A good approach is to select all three of these, just to be on the safe side. Notice that the Mac OS platform is preselected and dimmed.

6. If you want to change either the physical dimensions of your image or its resolution, click the Resize Images check box, then do one or both of the following:

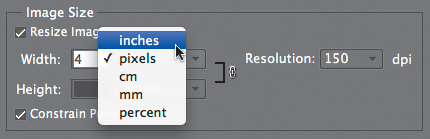

![]() To convert all of your images to a specific size, first select a unit of measure from the units drop-down menu, then enter the width or height in the appropriate text box, making sure that the Constrain Proportions check box is selected (Figure 13.12).

To convert all of your images to a specific size, first select a unit of measure from the units drop-down menu, then enter the width or height in the appropriate text box, making sure that the Constrain Proportions check box is selected (Figure 13.12).

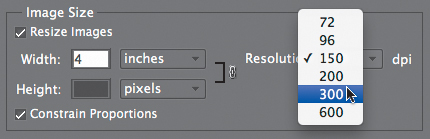

![]() From the Resolution drop-down menu, choose a resolution in dots per inch (dpi) to change the resolution of all your images (Figure 13.13).

From the Resolution drop-down menu, choose a resolution in dots per inch (dpi) to change the resolution of all your images (Figure 13.13).

Figure 13.11 Choose from a number of file naming options to arrange your images in consecutive order.

Figure 13.12 You can resize entire groups of images to the same width or height dimensions.

Figure 13.13 Choose a resolution to apply to all of the files in your selected group.

Figure 13.14 Choose a formatting option to apply to all the files in your selected group.

The resolution setting in this dialog is in dots per inch (print resolution) rather than pixels per inch (screen resolution), so changing just the resolution here will do nothing to alter your image, or change its file size. It changes only the dimensions of the final printed image and has no effect on the size it displays onscreen. (For more information on image resizing, see “Changing Image Size and Resolution” in Chapter 3.)

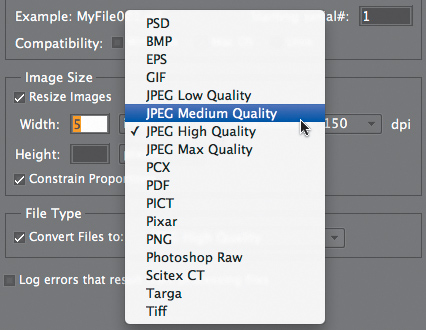

7. From the Convert Files to drop-down menu, choose the desired format type (Figure 13.14).

8. Click OK to close the dialog and start the batch process. The selected files are opened, converted in turn, and then saved to the folder you’ve chosen.

If you’ve chosen one of the import options, an additional series of dialogs appears, guiding you through the selection of images to import.

![]() Tip

Tip

![]() Using a little simple math can help you to convert pixel dimensions to inches. Just multiply the resolution you’ve selected by the number of inches (of either height or width) that you want your final image to be. For example, if you’ve selected a resolution of 72 dpi, and you want the width of your images to be 4 inches; simply multiply 72 by 4, then enter the total (288) in the width text box.

Using a little simple math can help you to convert pixel dimensions to inches. Just multiply the resolution you’ve selected by the number of inches (of either height or width) that you want your final image to be. For example, if you’ve selected a resolution of 72 dpi, and you want the width of your images to be 4 inches; simply multiply 72 by 4, then enter the total (288) in the width text box.

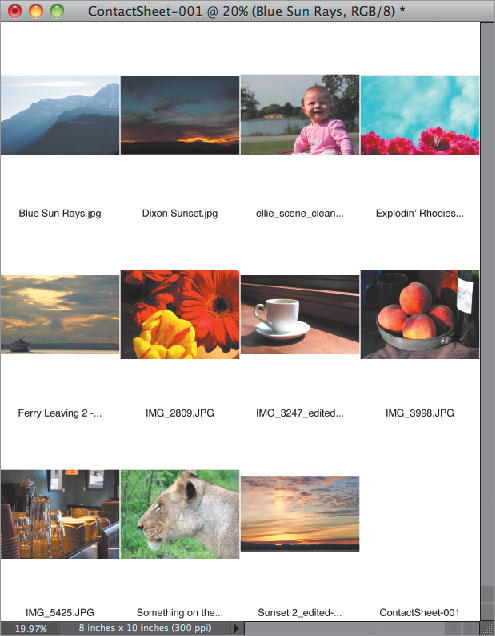

Creating a Contact Sheet

You may have lots of photos downloaded from your digital camera, but with unhelpful filenames like 102-0246_IMG.JPG, organizing and sorting them can be a difficult task. And although Bridge lets you view and sort through your images, sometimes it’s nice to have a printed hard copy to study and mark up. In traditional photography, contact sheets are created from film negatives and provide a photographer or designer with a collection of convenient thumbnail images organized neatly on a single sheet of film or paper. The Contact Sheet feature works in much the same way.

To make a contact sheet:

1. Do one of the following:

![]() In Bridge, select the photos you would like to include in your contact sheet and then choose Tools > Photoshop Elements > Contact Sheet II.

In Bridge, select the photos you would like to include in your contact sheet and then choose Tools > Photoshop Elements > Contact Sheet II.

![]() In Photoshop Elements, open the files you want and choose File > Contact Sheet II.

In Photoshop Elements, open the files you want and choose File > Contact Sheet II.

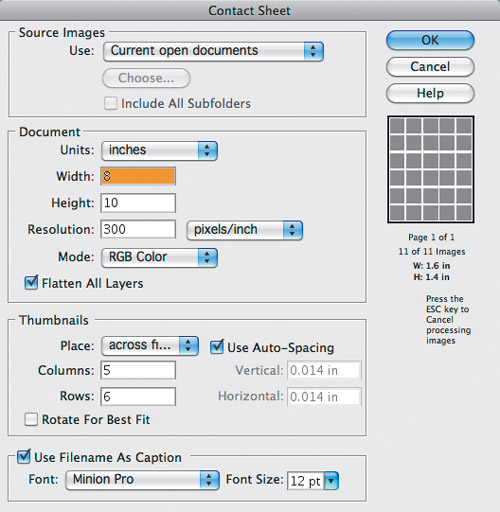

The Contact Sheet dialog opens (Figure 13.15). If you came from Bridge, the Source Images drop-down menu reads Selected Images from Bridge. If you opened the dialog from within Photoshop Elements, you may need to choose Current open documents. You can also choose Folder and specify a folder of images on your hard disk.

2. Specify the paper size, printing resolution, and color mode of the printer you’re using.

3. In the Thumbnails pane, choose how the photos will be arranged on the page by specifying the number of columns and rows, and choosing a sort order. You can also control the spacing between images or leave it set to Auto-Spacing.

Figure 13.15 Set up printing options in the Contact Sheet dialog.

Figure 13.16 The contact sheet is assembled and ready for printing.

4. If you want each image to be labeled with its filename, mark the Use Filename as Caption check box and specify a font and size for the text.

5. Click OK.

Elements builds the contact sheet before your eyes (it actually runs a script that opens each image, resizes it, and places it in a new document). After a short time, the contact sheet is assembled and ready for printing (Figure 13.16).

![]() Tip

Tip

![]() Building a contact sheet is a memoryintensive task. If Photoshop Elements doesn’t have enough memory to do the job, a dialog will alert you. Close other programs and try again.

Building a contact sheet is a memoryintensive task. If Photoshop Elements doesn’t have enough memory to do the job, a dialog will alert you. Close other programs and try again.

Creating a Picture Package

Photoshop Elements’ Picture Package creates a page with multiple copies of the same image, just like the kind you’d receive from a professional photographer’s studio. Printing images this way is also more economical, because you waste less photo paper.

To make a picture package:

1. Do one of the following:

![]() In Bridge, select the photos you would like to include in your contact sheet and then choose Tools > Photoshop Elements > Picture Package.

In Bridge, select the photos you would like to include in your contact sheet and then choose Tools > Photoshop Elements > Picture Package.

![]() In Photoshop Elements, open the files you want and choose File > Picture Package.

In Photoshop Elements, open the files you want and choose File > Picture Package.

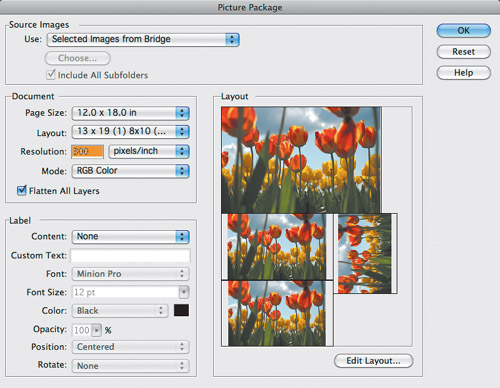

The Picture Package dialog opens (Figure 13.17). If you came from Bridge, the Source Images drop-down menu reads Selected Images from Bridge. If you opened the dialog from within Photoshop Elements, you may need to choose Current open documents. You can also choose File, Folder, Frontmost Document, and Open Files.

2. Specify the paper size, printing resolution, and color mode of the printer you’re using. The Layout drop-down menu determines how the images are arranged, which you can preview in the Layout pane.

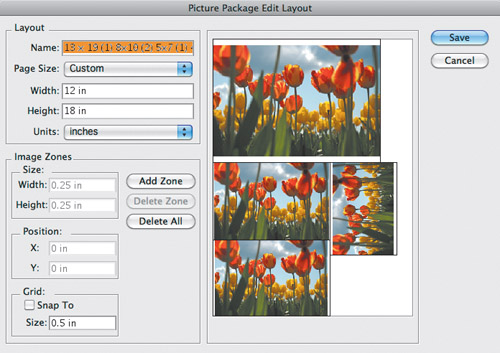

3. To change the layout, click the Edit Layout button and fine tune the appearance of the page (Figure 13.18). Click Save to apply the changes.

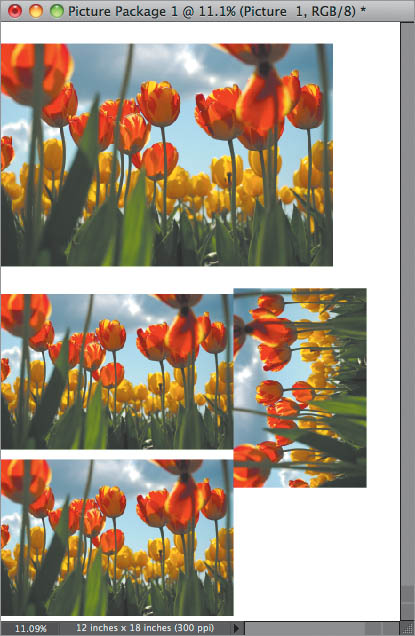

4. Click OK.

Elements builds the picture package, creating a new file for every page (Figure 13.19).

Figure 13.17 A picture package creates pages that include multiple sizes of each image.

Figure 13.18 Edit the layout of the picture package page.

Figure 13.19 The finished picture package.

Figure 13.20 The Photoshop Elements Print dialog.

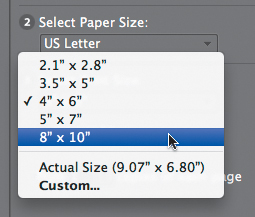

Figure 13.21 Choose the size the photo will be on the printed page.

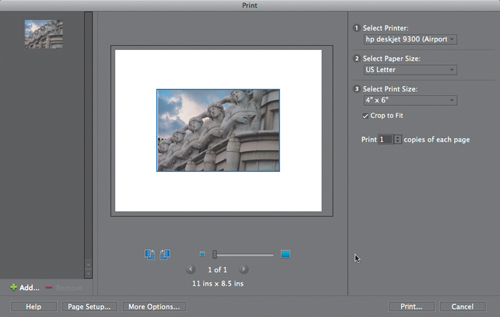

Printing an Image

Many photographers create their own prints instead of sending files to a print service, which you can do easily from within Photoshop Elements.

To print an image:

1. From the File menu, choose Print to open the Print dialog (Figure 13.20).

2. Select a printer and optionally adjust settings specific to it from the Select Printer and Select Paper Size options.

3. Click the Select Print Size drop-down menu and choose the size at which the image will print (Figure 13.21). The page preview reflects the page size in proportion to the image you want to print.

Choosing Custom opens the More Options dialog, which lets you specify a custom size.

4. Specify the number of copies of each page to print.

5. To customize the appearance of the image on the printed page, click the More Options button and see the next page.

6. Click the Print button to send the job to the printer.

Setting more printing options

Elements offers optional print settings for adding more information to your prints. They can be helpful when printing drafts or outputting images for other projects.

To set more printing options:

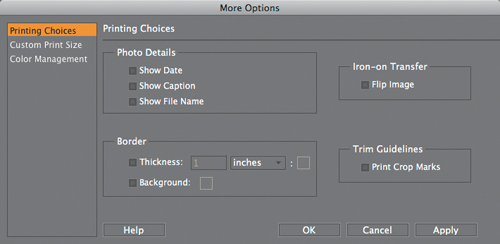

1. Before you print, click the More Options button and, in the dialog that appears (Figure 13.22), do one of the following:

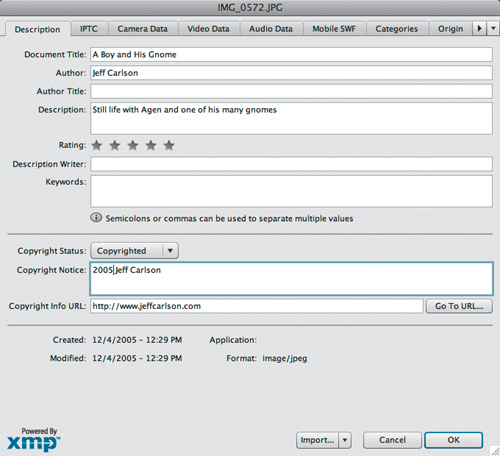

![]() In the Photo Details area, click the checkboxes to display an image’s date, caption, or file name. If a document title or description has been entered for the image in the File Info dialog, it will be represented in the page preview as gray bars. The document title (File Name) appears at the top, and the description (Caption) appears at the bottom (Figure 13.23). (See the sidebar “Adding Personalized File Information” earlier in this chapter.)

In the Photo Details area, click the checkboxes to display an image’s date, caption, or file name. If a document title or description has been entered for the image in the File Info dialog, it will be represented in the page preview as gray bars. The document title (File Name) appears at the top, and the description (Caption) appears at the bottom (Figure 13.23). (See the sidebar “Adding Personalized File Information” earlier in this chapter.)

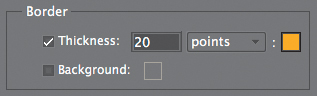

![]() In the Border area, click the Thickness check box and specify a width for the line (Figure 13.24). Click the small color swatch to the right to select the border’s color. You can also set a background color for the page.

In the Border area, click the Thickness check box and specify a width for the line (Figure 13.24). Click the small color swatch to the right to select the border’s color. You can also set a background color for the page.

![]() If you’re making transfers for t-shirts, click the Flip Image check box under Iron-on Transfer to invert the image horizontally. (If your printer’s driver has an invert image option, make sure that’s not selected—otherwise, the image will flip back to its original orientation when printed.)

If you’re making transfers for t-shirts, click the Flip Image check box under Iron-on Transfer to invert the image horizontally. (If your printer’s driver has an invert image option, make sure that’s not selected—otherwise, the image will flip back to its original orientation when printed.)

![]() Under Trim Guidelines, click the Print Crop Marks button to include crop marks (Figure 13.25).

Under Trim Guidelines, click the Print Crop Marks button to include crop marks (Figure 13.25).

2. Click the Apply button to view the changes in the preview without leaving the More Options dialog. Or, click OK to return to the Print dialog.

Figure 13.22 The More Options print dialog.

Figure 13.23 Photo details appear as simple gray bars in the preview window.

Figure 13.24 Select a measurement unit and size for your border.

Figure 13.25 Crop marks positioned at the corners.