Introduction

The aim of this book has been to contest the belief that there is an inevitable, inescapable and irreversible shift towards a formal market economy in post-Soviet societies by re-evaluating the role of informal economies in this region of the world. In this chapter we synthesise the findings from the previous chapters to reach some conclusions on the role of informal economies in post-Soviet societies. To do this, and following the structure of the book, first, we review the theoretical and conceptual framework we have advocated for rethinking the role of informal economies in the post-Soviet world and, second, display how using this as a lens enables one to more fully understand not only that households draw upon a plurality of economic practices to secure their livelihood in post-Soviet spaces, but also how the nature, role and meaning of these diverse work practices vary across different population groups.

(Re)theorising transition economies

In order to understand the role that informal economic practices play in securing a livelihood and getting by in post-Soviet spaces, Part I of this book outlined a theoretical and conceptual framework for rethinking this issue. In Chapter 2 we revisited the recurring question of transition in order to dispute not only the past hegemony of the command economy system, but also the notion that there is a universal linear trajectory of development in post-Soviet spaces towards a hegemonic ideal-type formal market economy system as some end-point. Instead, we called for a more nuanced argument to be adopted that allows it to be recognised how there has been a transformation of post-Soviet economies in varying ways from different starting points and along different economic development trajectories.

Chapter 3 then turned its attention to contesting the myth that the advent of a hegemonic formal market economy is an inevitable and natural process and that no other options exist regarding the trajectory of economic development. On the issue of the inevitability of a formal market economy, this chapter made it very clear that a future where the formal market economy becomes hegemonic is not cast in stone. Indeed, to assert that the formal market economy is unavoidable is to fly in the face of the empirical evidence on the trajectories of post-Soviet economies. On the issue of whether the advent of a formal market economy is a natural process, meanwhile, this chapter revealed that the formal market economy is not an autonomous sector that grows with little or no help. Rather, it is argued to have been energetically facilitated and sustained by a barrage of intervention. Taking this into account, it has been asserted that one has to consider quite how widely and deeply the formal market economy would have permeated the post-Soviet world without such massive intervention and encouragement. If the formal market economy has only captured such a minor share of all economic activity even when governments have so actively intervened to encourage its growth, then one does wonder quite how expansive the formal market realm would have been if left to its own devices. Given this continuous and ongoing nurturing and support by government, it is thus obvious that the formal market economy is not an organic process. Once recognised, then the future trajectory of economic development becomes more open. Seeking to develop the formal market economy through controlled interventionism and paying little heed to the development of work beyond the formal market economy becomes clearly recognised as but one option available regarding the trajectory of economic development.

The outcome has been a rethinking of the ‘economic’ and an opening up of economic development as an ‘undefined, open-ended, heterogeneous transformative process’ (Chowdhury 2007: 10). Rather than view post-Soviet spaces as lagging behind the west by reducing difference to backwardness, this chapter opened up the future to other possibilities beyond a totalising formal market economy. Our project, therefore, has been to deconstruct the familiar notion of economic development as a transition to a formal market economy by revealing that formal market economic practices are just one of a plurality of economic practices in post-Soviet spaces, thereby decentring the formal market economy and recovering alternative futures for economic development so as to disrupt dominant economic discourses about the future of post-Soviet economies as being towards a totalising formal market economy. However, our intention has not been to replace one universal conceptualisation of the trajectory of economic development with another alternative universal.

Instead, we have argued that not only is the informal and non-market economy persistent and even growing in many post-Soviet spaces (negating the formalisation and marketisation theses), but also that the role they play in contemporary post-Soviet spaces is not always the same and that it varies according to both the type of informal work being considered and the population groups and places being evaluated. Reviewing the competing theoretical perspectives on the role of informal economies in contemporary economies, Chapter 3 concluded by raising the possibility that some forms of informal work might be a by-product of the changes in the formal market economy in some places and among some populations groups, while other forms of informal work will act as complements and yet others as alternatives to the formal market economy.

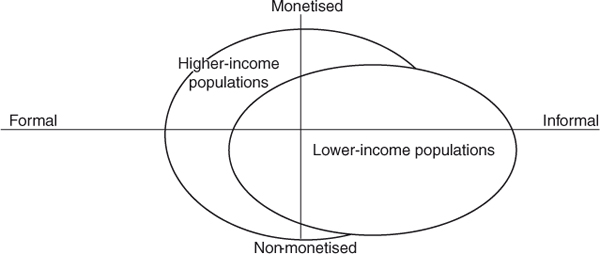

To move beyond an understanding of the economic and economy which is centred on the impending hegemony of a formal market economy and to gain greater understanding of the role that informal economies continue to play in people’s livelihood practices, chapter 4 adopted a ‘whole economy’ perspective and constructed an analytical lens for understanding the multiple labour practices which exist in contemporary economies. Transcending the simplistic formal/informal economy dichotomy, and developing the ‘total social organisation of labour’ conceptual framework proposed by Glucksmann (2005), this conceptualised a spectrum from formal-oriented to informal-oriented labour practices, which is cross-cut by another spectrum ranging from wholly monetised to wholly non-monetised labour practices.

The resultant outcome is to capture the plurality of labour practices that exist in post-Soviet societies in a manner which shows how they all seamlessly merge into each other.

Having developed this analytical lens for understanding the ‘diverse economies’ of the post-Soviet world, Chapter 4 then used this to provide an over-arching understanding of the multifarious labour practices used in Ukraine and Russia. Analysing the results of 600 interviews conducted across various populations in Ukraine and 313 interviews conducted in Moscow, this revealed the shallow permeation of the formal market economies in Ukraine and Russia that have been supposedly undergoing a ‘transition’ to formal market economies. It also revealed the existence of diverse work cultures across different populations, along with marked socio-spatial variations in the nature of individual labour practices. To begin to develop a deeper understanding of these socio-spatial variations in individual labour practices, Part II then evaluated the various labour practices that are used to secure a livelihood in post-Soviet societies.

The lived experiences of transition

To begin to develop a deeper understanding of the role that informal economic activities play in securing a livelihood in post-Soviet societies, as well as the socio-spatial variations, each form of informal economic activity has been evaluated in turn. Displaying the need to transcend the formal/informal economy dichotomy, Chapter 5 examined the role played by formal employment in securing a livelihood, and more precisely how in post-Soviet societies the formal economy is so infused with informality that it is difficult, if not impossible, to differentiate formal and informal labour practices. Chapter 6 then evaluated the role played by informal employment, Chapter 7 the roles played by paid favours, reimbursed family work and one-to-one unpaid labour, Chapter 8 formal unpaid employment and informal unpaid employment and Chapter 9 self-provisioning. The intention in doing so has been to display the prevalence of these forms of labour in everyday livelihood practices in post-Soviet societies in order to show, on the one hand, how the transition to a hegemonic formal market economy is far from achieved, and on the other hand, the prominent role of informal economic activities in everyday livelihood practices in the post-Soviet world.

In Chapter 5 it was revealed that despite all of the hyperbole about the hegemony of the formal market economy, just 59.2 per cent of the working-age population is employed in the formal economy. This means that four in every ten people of working age in the post-Soviet world do not participate in the formal economy. Even this, however, is an exaggeration of the reach of formalisation in post-Soviet societies. Many of those who are in formal employment are in jobs infused with informality. Some one in eight formal employees receive an envelope wage and this on average amounts to 38 per cent of their wage packet. The result is that even if 59 per cent of the working-age population is engaged in formal employment, one in eight of these occupy quasi-formal jobs. This not only blurs the divide between formal and informal jobs, but also means that the proportion in purely formal employment is even lower than previously assumed. This, however is not the only way in which the formal economy is infused with informality. As the case studies of kindergartens, schools, the university system, entry into the graduate labour market and healthcare provision revealed, the formal economy in post-Soviet societies remains riddled with crime, informality and corruption. In doing so, this chapter revealed that it is impossible to view the formal and informal economies as separate and discrete spheres. Informality is an inherent feature of the formal economy in post-Soviet societies.

Chapter 6 then turned its attention to the role played by informal employment and showed that it is not some small residue that is steadily disappearing from view in post-Soviet economies. As Schneider (2012) reveals, its magnitude is equivalent to 32.6 per cent of GDP across post-Soviet economies, and although it has declined slightly over the last few years relative to the formal economy, it remains a sizeable feature across all post-Soviet societies. Indeed, examining the results of the surveys conducted in Ukraine and Moscow, informal employment was found to play a central role in the livelihood practices of a large proportion of households. Indeed, some 40 per cent of Ukrainian households cite informal employment as either the principal or secondary contributor to their living standard and 43 per cent in Moscow. Examining their reasons for engaging in informal employment, moreover, in Ukraine 30 per cent of informal employment is explained purely in terms of exclusion from the formal economy, 35 per cent purely to avoid the costs, time and effort of formal registration and in preference to formal employment, and 13 per cent purely for social and/or redistributive reasons, with the remaining 22 per cent a mix of these rationales. Similar levels of reliance on informal employment and diversity in the rationales among those engaged in informal employment was identified in Moscow.

Despite this heavy reliance on informal employment in both countries and similar rationales being expressed for engaging in this work, the configuration of informal employment differs markedly across the two countries. The finding is that in Moscow 78 per cent is informal self-employment and 22 per cent is waged informal employment. In Ukraine, in contrast, 38 per cent is informal self-employment and 62 per cent waged informal employment. Yet despite this, the rationales for engagement in each type of informal employment and by each population group are markedly similar in both countries. Voluntarism, and therefore the neo-liberal and post-structuralist theorisations, is more commonly cited by those engaged in informal self-employment and those living in higher-income households, rural and affluent localities. Exclusion from the formal economy, meanwhile, is more commonly cited among those engaged in waged informal employment and among low-income households, and those living in urban and deprived areas.

It is important to be aware, however, that even if some types of explanation are more common for some types of informal employment than others, there remains tremendous diversity in the rationales for participating in each type of informal employment among different population groups. In other words, there is a rich tapestry of both types of informal employment and reasons for engaging in them in these post-Soviet societies that cannot be neatly captured by promulgating universal hues. Just as one would not draw universal generalisations about formal waged employment and formal self-employment when evaluating its nature or the reasons for engaging in such work, it is similarly erroneous to do so when considering the informal labour market in post-Soviet societies.

Chapter 7 then turned its attention to the prevalence and nature of three forms of one-to-one exchange in post-Soviet societies, namely one-to-one unpaid labour, reimbursed family work and paid favours. This revealed that in both Ukraine and Moscow unpaid one-to-one labour is more prevalent among lower-income populations, where it is more likely to be conducted for and by kin, not least because they lack the financial purchasing power to use money or gifts, and/or physical wellbeing to reciprocate with in-kind labour, so engage in such exchange out of necessity. Higher-income populations, in contrast, use one-to-one monetised exchange more to expand their social networks and consolidate relationships and do so more out of choice. Deprived populations therefore use this when no other options are open to them, in order to ‘get by’, whereas for affluent populations it is conducted more as a matter of choice, in order to ‘get on’.

The chapter then examined the nature of a form of labour that has been seldom discussed in post-Soviet societies or beyond, namely paid family labour whereby a household member reimburses another household member for work conducted. This reimbursement can be in the form of money, but also in the form of gifts or the in-kind reciprocal exchange of labour. The overarching finding was that reimbursed family labour constitutes a small but significant livelihood practice in post-Soviet spaces. Mostly involving inter-generational exchanges between a parent and child, such a labour practice is most common in more affluent populations. In lower-income populations where such a labour practice is less frequent, when it does occur, it more commonly involves gifts and/or in-kind reciprocity rather than monetary exchange. The notion that the existence of such a labour practice marks the advent of a marketisation of the domestic realm, however, does not appear to be valid. Examining the rationales underpinning such exchanges, there is little notion that the participants in such practices view themselves as engaged in market-like profit-motivated exchanges. Broader social and redistributive rationales, such as the desire to impart an understanding of the meaning of money, were found to be more to the fore in terms of the participants’ motives than profit-motivated rationales, and nor did they perceive these exchanges as akin to market-oriented exchanges conducted for the purpose of profit.

Turning to paid favours, Chapter 7 then revealed in both Ukraine and Moscow the existence of a continuum of forms of paid favours from those closer to informal self-employment conducted for profit-motivated rationales through to those more akin to mutual aid in terms of the social relations and motives involved. Those closer to profit-motivated informal self-employment are conducted mostly for more distant acquaintances, and are also more prevalent among higher-income populations, while those where the profit motive is largely absent, are redistributive and social rationales prevail are undertaken largely for closer social relations and are more prevalent in lower-income populations.

Chapter 8 then transcended the widespread assumption that when one engages in formal employment, it is always paid labour. Reviewing the persistence and even growth of unpaid internships in the private, public and third sectors of the economy, which many people now undertake in order to gain work experience and improve their employability, as well as the existence of trials on an unpaid basis so that employers can judge the suitability of an applicant for a post, as well as the growth of formal volunteering in the third sector, this revealed that formal unpaid labour certainly exists in the private and public sectors. In these sectors, young people, in order to gain much needed work experience and often to get a ‘foot in the door’, often undertake it. In the private sector, though, there is evidence that employers potentially use this method as a means of employing ‘free’ labour so as to reduce labour costs and hence increase a firm’s profitability. Moreover, there is also evidence of formal unpaid labour occurring when employers (in both the private and public sectors) fail to pay employees’ full wages. While this problem has considerably improved since the chaotic days of the 1990s, where wage arrears were a major problem, the problem still exists and one which has seemingly been exacerbated in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Regarding unpaid labour in the third sector, this certainly exists but importantly is rarely used to meet the material needs not met by other fields of provision, such as the formal market economy. Individuals engage in community-based associations to fulfil their own needs rather than to deliver material support to others. As such, if the intention in Ukraine and Russia is to encourage the development of civil society in order to meet material needs not met by the formal private and public sectors, or even other forms of informal delivery, then developing participation in community-based groups is inappropriate. This chapter then addressed a labour practice that has seldom been analysed in post-Soviet societies, namely informal unpaid employment, which is where somebody is employed by an organisation on an unpaid basis, but the employer or employee does not adhere to all the rules and regulations required. This revealed that such work often prevails because employers and workers engaged in unpaid employment do not realise that the legal responsibilities that apply to paid employment are also applicable to unpaid employment, such as indemnity insurance, or health and safety legislation.

Chapter 9 then addressed the practice of self-provisioning, often assumed to be a leftover from a previous mode of accumulation, and that the small vestiges that remain will eventually disappear as the formal market economy became ever more dominant (e.g. Smuts 1971; Watts 2001). This reveals the extensiveness of self-provisioning in post-Soviet societies and how it is possible to differentiate between ‘willing’ (rational economic actors, choice, identity seeking) and ‘reluctant’ (economic and market necessity, dupes) participants in self-provisioning. Not only is self-provisioning a ubiquitous practice which a significant minority of households in both Ukraine and Moscow rely heavily on to secure their livelihood, but the vast majority of everyday tasks in households are conducted on a self-servicing basis. The clear implication is that everyday life in Ukraine and Moscow is more a ‘do-it-yourself’ rather than a ‘do it for me’ culture. Some households, moreover, do more on a self-provisioning basis than others. Indeed, the lowest-income households conduct more on a self-provisioning basis than the highest-income households. This, however, is not because it is purely a product of economic necessity.

Economic necessity is more common as an explanation in lower-income households, but cannot be relied on exclusively to explain all self-provisioning. A fuller and more comprehensive explanation for self-provisioning requires a move beyond this simplistic explanation. As has been here revealed, some self-provisioning is conducted on a ‘willing’ basis by those who engage in such endeavour either as a rational economic calculation, for pleasure, or to seek self-identity from the end-product, while other self-provisioning is conducted on a ‘reluctant’ basis by those forced into such endeavour either for economic reasons or due to problems with finding and using tradespeople. The finding is that although reluctant self-provisioning is more likely among lower-income populations, in higher-income populations people are markedly more likely to be willing participants. Overall, however, self-provisioning in these post-Soviet economies is a persistent, important and pervasive feature of the economic landscape in the post-Soviet world. With this in mind, we now turn our attention to drawing some conclusions about the role of informal economies in the post-Soviet world.

The role of informal economies in the post-Soviet world

Since the demise of the socialist bloc, the recurring belief has been that post-Soviet societies are in transition to capitalism. Indeed, Kostera (1995) has likened the intervention and investment to facilitate this advent of capitalism to a religious crusade, with management educators and consultants acting like missionaries spreading the cult of what Parker (2002) calls ‘market managerialism’. However, this book has revealed that in post-Soviet societies a plurality of labour practices are pursued. One important finding is the relatively shallow penetration of the formal market economy although the depth to which it has permeated everyday life varies socio-spatially. Another finding is that work cultures also vary. Those living in affluent populations adopt more formal and monetised work cultures, while those in lower-income populations are more reliant on community exchanges between closer social relations, both of the monetised and non-monetised variety, as well as self-provisioning (see Figure 10.1).

The character of each labour practice also varies socio-spatially. On the whole, affluent populations engage in a greater range of labour practices, and do so out of choice, while deprived populations employ a narrower range of practices which they engage in more out of necessity in the absence of alternatives. The outcome is that uneven development in Moscow and Ukraine is not characterised by affluent populations being more formalised and monetised. Rather, uneven development is characterised by a polarisation between ‘work busy’ populations engaging in a wide array of labour practices and doing so more commonly out of choice, and ‘work deprived’ populations engaging in a narrower range of labour practices which they do more commonly out of necessity. Depending on the types of informal work and populations studied, different representations of the informal economy are appropriate. When considering the limited number of households pursuing subsistence modes of production, for example, and how very few households remain untouched by the formal economy, the residue perspective appears valid. Indeed, this is further reinforced by subsistence households, especially in the deprived rural area of Ukraine, who assert that their numbers are dwindling as the young leave the countryside and move to the towns in search of formal employment.

When considering other types of informal work, however, it is the representation of the informal economy as a by-product of a new emergent form of capitalism that is using informal working arrangements to compete and off-loading onto the informal sector those no longer of use to it which is valid. Support for this comes not only when examining forms of informal waged employment such as ‘envelope wages’ and sweatshop-like work, as well as routine self-provisioning, but also when wider trends are recognised such as that participation in the informal economy is much greater among lower-income populations. Yet to depict all of the informal economy in this manner is a misnomer.

As the evidence in support of the representation of the informal economy as a complement to the formal economy clearly displays, informal work, at least in some of its varieties, is often not a sphere inhabited purely by the marginalised, but rather, is a realm which reinforces, rather than reduces, the socio-spatial disparities in the formal economy. This is exemplified in the realm of do-it-yourself activity, for example, as well as the sphere of paid favours. There are also types of informal work that are a chosen alternative to the formal economy. Not only is there a culture of resistance to immersion in the formal economy, at least among some engaged in subsistence production as their primary work strategy, but the extensive ‘hidden enterprise culture’ of off-the-books enterprise and entrepreneurship being pursued as a widespread resistance practice to the (in their eyes) over-excessive regulation and state corruption, provides solid support for the depiction of informal work as a chosen alternative.

The result is that although varying discourses are appropriate as representations of different types of informal work, no one articulation fully captures the diverse nature and multiple meanings of the informal economy in Ukraine and Moscow. However, if we transcend the view that these are competing discourses and recognise that each is a depiction of particular types of informal work, as Chen (2006) most prominently has suggested, then it becomes quickly obvious that by incorporating all of them a finer-grained and more comprehensive understanding of the complex and diverse meanings of the informal economy can be achieved.

How, therefore, might these articulations be coupled together to reach this more holistic understanding? At first glance, this appears unachievable. On the one hand, in the representations of the informal economy as a residue and an alternative, the formal and informal economies are viewed as discrete and separate, while in the discourses of the informal economy as a complement to, and by-product of, the formal economy, they are viewed as inextricably inter-related. Indeed, much of the contemporary literature that views formal and informal work as entangled vehemently opposes any notion of separateness (e.g. Smith 2004; Smith and Stenning 2006).

In lived practice, however, some forms of informal work are relatively entangled in the formal economy and others relatively separate. ‘Envelope wages’, where formal employees are paid a portion of their wages on a cash-in-hand basis, for example, provide solid support for the depiction of formal and informal work as inextricably inter-related. Yet this intimate entanglement of formal and informal work is not apparent when examining most forms of self-provisioning. There is a case to be made, therefore, for recognising a spectrum of informal work ranging from varieties that are relatively separate from the formal sphere to those that are relatively intertwined with the formal economy (e.g. ‘envelope wages’). On the other hand, while the residue and by-product perspectives universally attribute the informal economy with exclusion or necessity, the complementary and alternative approaches do the inverse and view such practices to result from a desire to exit the formal realm or choice. However, it is again wholly feasible to conceptualise a continuum of types of informal work ranging from those where choice is more likely to prevail (e.g. paid favours, unpaid community exchange, informal entrepreneurship) to those where exclusion is more prevalent (e.g. exploitative ‘sweatshop’-like informal waged employment).

These discourses, therefore, do not need to be seen as rival and contradictory representations of the informal economy. Instead, they can each be read as valid depictions of particular types of informal work which need to be integrated together to achieve a finer-grained and fuller understanding of the diverse nature of the informal economy. Indeed, this is now starting to be recognised (e.g. Chen 2006). How they can be joined together to provide a more holistic understanding, nevertheless, has not been so far discussed. Here, a first attempt is made to do so. Figure 10.2 provides a graphic representation of how this might be accomplished. The four contrasting discourses are here used to depict particular types of informal work that exist on, first, a spectrum that ranges from forms of informal work that are relatively separate from the formal economy to types that are heavily embedded in the formal economy, and second, a spectrum of the reasons for engagement from pure exclusion at one end to pure exit at the other.

If adopted when analysing the informal economy, this integrative conceptual framework that facilitates an understanding of the multifarious nature of labour practices would have important impacts on how we think about informal work. First, adopting such a conceptual framework would enable the persistent debates between rival discourses that contest each others’ viewpoint despite them talking about different forms of informal work (e.g. neo-liberals on informal self-employment and post-Fordists on informal waged employment) to be transcended. It might also begin to put a stop to the all-too-common occurrence whereby discourses simply focus upon those forms of informal work conforming to their depiction of informal work while ignoring those that do not. As Samers (2005) has highlighted, for instance, post-development theorists viewing informal work as a chosen alternative seem to display a myopic disregard for forms of informal work that do not conform to their depiction, such as low-waged sweatshop-like informal employment. This, however, is not unique to these commentators. It applies across the spectrum of discourses.

Second, adopting this more integrative conceptual framework might also start to result in more nuanced policy approaches towards informal work. At present, a largely negative approach predominates, reflecting the dominance of the residue and by-product perspectives. This is particularly the case when considering what needs to be done about undeclared work where the dominant approach is to eradicate such work by increasing the probability of detection and the penalties if caught (Williams 2004a, 2006b). It is similarly the case when considering other forms of informal work. Few, if any, governments move beyond an employment-centred discourse when discussing economic development. If the above conceptual framework were adopted, however, then this would help identify those forms of informal work that need to be eradicated and those that need to be either transformed into formal employment or tacitly condoned rather than adopting a ‘one size fits all’ public policy approach which treats all types the same.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, this more holistic framework might also help the long-standing but simplistic arguments about whether formalisation or informalisation is the path to progress to be finally transcended. Rather than an ‘on–off’ decision about whether formalisation or informalisation is the way forward for economic development, more nuanced and finer-grained debates about the nature and direction of urban and regional economic development could perhaps start to emerge that pursue a more ‘pick and mix’ approach so far as various types of informal (and formal) work are concerned.

In sum, this book finds that the representation of market hegemony has prevented the recognition, valuing and even developing of other (and ‘othered’) labour practices beyond the formal market economy. In this book an alternative theoretical framework and analytical lens for capturing and ordering these multiple labour practices has been developed which portrays labour practices more fluidly, showing how they are not separate discrete practices but are seamlessly entwined and conjoined. This has enabled a rethinking of labour relations and the lived practice of economic transition in post-Soviet societies. If it is now applied more widely to understanding the multiplicity of labour practices in not only the post-socialist world but also so-called advanced western economies and the majority (third world), then this book will have achieved its principal intention. If this then begins to stimulate deliberation of the feasibility of, and possibilities for, alternative futures beyond market hegemony, then it will have achieved all of its objectives.