2 Core democratic values

and orientations1

‘Should China adopt a democratic political system?’ and ‘What kind of democratic political system should China have?’ are still hotly debated questions inside and outside China. Regardless of the outcome of this debate, it is probably inevitable that China will, sooner or later, engage in meaningful democratic reform of its political system as social and economic problems reach boiling point. When that happens, will the Chinese people be ready to live in such a system and make it work? In general, it is assumed that ‘the development of a stable and effective democratic government depends upon the orientations that people have to the political process upon the political culture.’2 As Gibson and Duch point out, ‘Democratization is more than the simple imposition of formally democratic institutions on a polity’; and people's beliefs can either constrain or promote a ‘structural process of democratization.’3

Historically the Chinese peasantry in Confucian tradition has been viewed as a conservative social and political force. A popular view still prevalent among intellectuals and the general population in China is that the peasantry is one of the main obstacles to Chinese democracy because of its conservative political culture. This is despite meaningful villager committee elections, which take place in many Chinese villages, and recent scholarship which suggests that Chinese peasants are very conscious about their rights and are willing to protect them through ‘rightful resistance.’4 Some scholars even suggest that it could be the Chinese countryside leading the rest of the country to nationwide democracy.5 Nevertheless, Chinese peasants are still too often perceived to be adherents to authoritarian culture. The absence of democracy in China is often blamed on the Chinese peasants who are thought to have a low level of democratic political culture and a lack of democratic traditions.

Is this popular and negative view of the Chinese peasantry with regard to democratic values valid? What is the current status of democratic values among peasants in southern Jiangsu province? How do Sunan peasants compare to urban residents in Beijing in terms of their democratic values? What are the factors that might affect the support or lack of it for core democratic values among Sunan peasants? Answers to these questions are crucial in understanding and predicting political developments in China.

Support of core democratic values among southern Jiangsu peasants

As indicated earlier, it is assumed that the development of stable and effective democratic institutions depends heavily on citizens’ support of core democratic values. It is hard to imagine democratic institutions will survive in a political culture where there is serious lack of support for many key democratic values. Over the years scholars of political science have identified the following core democratic values: political tolerance, appreciation of liberties and freedoms, consciousness of civic/political rights, and support for competitive elections.6 It is these values which are tapped as the dependent variable in this chapter.

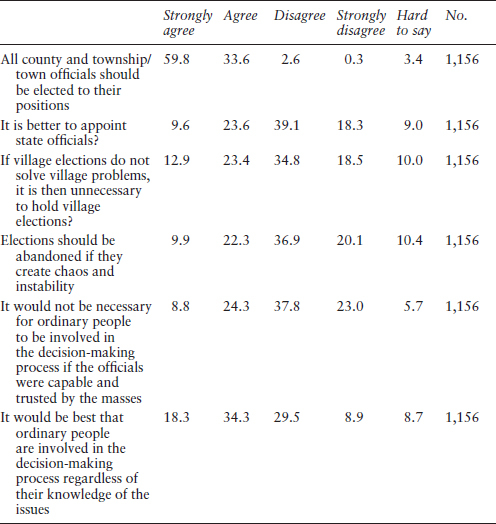

Findings presented in Table 2.1 show that peasants in the survey strongly endorsed democratic elections. An overwhelming majority supported the concept that township and county officials, who are currently not directly elected by voters, should be popularly elected to their positions. Close to 60 percent of the respondents seemed to support the idea that state leaders should also be promoted through elections. They were also asked whether all village party secretaries should be popularly elected, and an overwhelming majority (82 percent) said that they should. A major constraint and drawback in current village self-government in China is that the village party secretary is the most powerful cadre (or the ‘first-hand') and the elected villagers’ committee chairman is usually a deputy to the party secretary. Yet, the party secretary is not popularly elected. The lack of power held by the villagers’ committee chairman significantly reduced the meaningfulness and effectiveness of village elections in China (which will be explained further in Chapter 6).

It is even more surprising to find that a majority of our respondents were not willing to give up on democratic elections even if elected officials did not solve their problems. In other places, people often take a utilitarian approach toward democracy, believing that democracy will provide the means for solving specific problems. Yet most of the respondents in the survey seemed to insist on democratic elections even if they might not solve village problems. The findings for the question concerning potential chaos and instability resulting from elections were also telling. A majority of the respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement that elections should be abandoned if they created chaos and instability. It should be noted that the Chinese people, after experiencing centuries of upheavals, revolutions, and instabilities, have a special fear of chaos or luan. The chaotic Cultural Revolution is still fresh in people's minds. Therefore, the survey findings are especially interesting given the Chinese people's traditional concern for stability. Moreover, there was also a strong sense of popular participation. Over 60 percent of the respondents did not believe in elite politics and over 50 percent supported a citizen's right to participate regardless of knowledge and educational level. These findings contradict the negative perception of low political democratic culture among the Chinese peasantry.

Table 2.1 Selected democratic values I (%)

Source: Jiangsu Rural Survey 2000

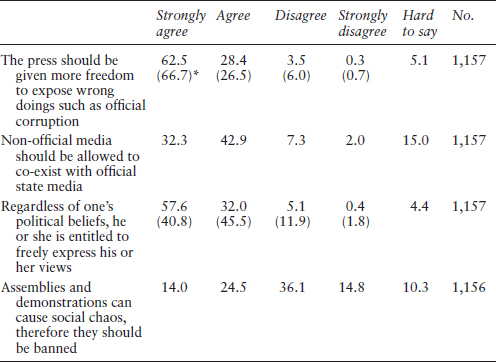

Table 2.2 presents findings on attitudes toward freedom of the press, tolerance, and political efficacy. Freedom of the press seems to be strongly favored by our respondents. An overwhelming majority believed that the press should be given more freedom to expose wrong doings, such as official corruption. A majority also thought that non-state controlled media should be allowed to exist alongside the official press. Close to 90 percent agreed that everyone was entitled to the same rights of free speech regardless of one's political beliefs. Again, these findings seem to defy the conventional wisdom that Chinese peasants are a socially and politically conservative force and hold values incompatible with democracy. In fact, on most of these questions, the peasant respondents in Jiangsu fared equally well or even better than the urban residents in Beijing.

Table 2.2 Selected democratic values II (%)

Note

*Figures in parentheses are combined findings from surveys conducted in Beijing in 1995 and 1997.

Source: Jiangsu Rural Survey 2000

The answers to the above questions were combined and tallied to form an additive index to capture a collective profile of a respondent's level of support for core democratic values. This index was used as the dependent variable in the multivariate analysis below.

Socio-political and economic factors influencing democratic values

Several socio-political and economic factors are used as independent variables to explain the formation and degree of support for the core democratic values held by peasant respondents in our survey. They are socio-economic satisfaction, income, political satisfaction, free-market values, political efficacy, a perceived need for political reform, and key socio-demographic variables.

Socio-economic satisfaction

In studying stability in democracies many scholars have identified ‘individual satisfaction with their socio-economic conditions’ as a key factor for the development and maintenance of a stable democratic system.7 However, a study conducted by Finifter and Mickiewicz in the former Soviet Union in the late 1980s showed that higher satisfaction with one's own life resulted in decreased receptivity to democratic change.8 In other words, they found that people who were more satisfied with their socioeconomic conditions tended to be more conservative in their political orientation. Even though there appears to be a difference between the established democracies and authoritarian societies in transition with regard to the relationship between personal life satisfaction and support for democratic values, the difference may not be real. The key is change or status quo. The proper hypothesis that can be proposed for both situations is probably that people living in either system who are more satisfied with their personal socio-economic conditions are less supportive of social change and more prone to maintaining the status quo. This is probably as true of people living in democracies as it is for people who live in authoritarian countries.

Based on the above analysis, I suspect that respondents’ life satisfaction influences their support for democratic values in a negative way. Evidence has shown that the new rich and people whose lives have significantly improved in recent years in China have indeed become politically conservative. The strategy of the Chinese Communist Party to improve its legitimacy by raising people's living standards (or eudemonism) has worked to a certain degree.9 Therefore it is hypothesized that peasants in the survey who felt more satisfied with their individual socio-economic conditions are less supportive of the core democratic values that could lead to a potentially drastic political change, that is, democratization.

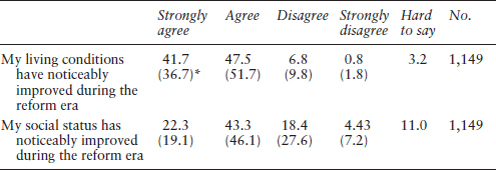

In this study I measured individuals’ satisfaction with their socioeconomic conditions by asking respondents to grade two statements: ‘My living conditions have improved in the reform era’ and ‘My social status has improved noticeably in the reform era.’ For both statements, respondents were asked to register their levels of satisfaction on a four-point scale in which ‘1’ (or ‘strongly disagree’ with the statement) stands for ‘very dissatisfied’ and ‘4’ (or ‘strongly agree’ with the statement) stands for ‘very satisfied’. Then numbers were tallied to form an additive index for each respondent that became the independent variable for socio-economic satisfaction. The results (see Table 2.3) are not surprising. An overwhelming majority (close to 90 percent) of the respondents agreed with the statement that their living standards had noticeably improved in the reform era while about 66 percent of them felt that their social status had likewise improved in the same period. In fact, compared with survey data gathered from Beijing in the late 1990s more people in southern Jiangsu province strongly agreed with the statement that their living conditions had noticeably improved in the reform era. However, it should be reiterated that southern Jiangsu province is one of the most economically developed rural areas in China.

Table 2.3 Levels of socio-economic satisfaction (%)

Note

*Figures in parentheses are combined findings from surveys conducted in Beijing in 1995 and 1997.

Source: Jiangsu Rural Survey 2000

Income

Income is closely related to the variable of life satisfaction. Income has long been used in western literature as an impact factor in political behavior and orientation. For example, there is a strong linkage between people with higher incomes and conservative political orientation and a preference for the status quo because of their vested economic interest in the existing system. Following the same logic on the relationship between life satisfaction and support for democratic values, it is hypothesized here that peasants in southern Jiangsu province with higher incomes tended to be less supportive of core democratic values since the latter might lead to drastic social and political changes in China.

Political satisfaction

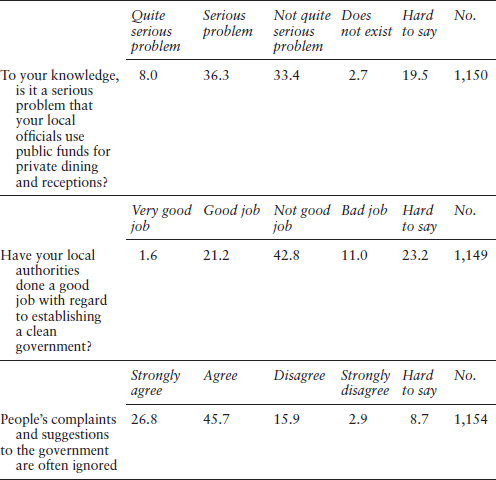

Political satisfaction is another independent variable used to account for the support of core democratic values. Political satisfaction refers to satisfaction with the political situation and government performance in the respondents’ locale. Following the same logic that explains the relationship between socioeconomic satisfaction and support for democratic values, people who are satisfied with the current political situation and government performance in China are probably less likely to support democratic values which have the potential to lead to fundamental changes in the political system. At the same time, people who are very unsatisfied with the political situation and government performance in China are more likely to support those values. Three questions were asked about political satisfaction, namely, assessment of the seriousness of the problem of local officials misusing public money for extravagant dining and receptions, the level of clean local government, and the responsiveness of local officials to local residents’ complaints and suggestions.

Findings from Table 2.4 are not surprising either. It seems that majority of the respondents were not satisfied with local Chinese government and government officials. Using public funds for private dining and receptions is a serious problem in China and has been a major source of public discontent in rural areas. The survey shows that close to half of the respondents felt that the problem was either very serious or serious in their locale, although close 20 percent were reluctant to express their opinion on this somewhat sensitive question. When they were asked what kind of job their local authorities had done with regard to establishing clean government, over 50 percent did not think their local authorities had done a good job. Again many were reluctant to answer the question. A much higher proportion agreed or strongly agreed that local government rarely reacted to their complaints and suggestions. Overall, there is a modest to high degree of public discontent with local government and local government officials among the peasant respondents. The answers to these questions were tallied and added to form an additive index to be used as the independent variable of political satisfaction in the multivariate analysis.

Table 2.4 Levels of political satisfaction (%)

Source: Jiangsu Rural Survey 2000

Support for free market economic reform

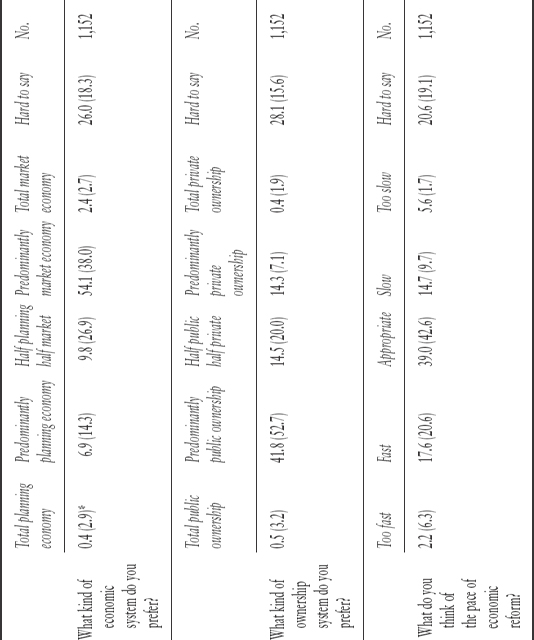

Many scholars have long argued that there is a strong correlation between a free market economic system and democracy.10 Not only does the positive relationship between a free market economy and democracy exist at the institutional level, the strong connection between the preference for a free market economy and democratic values is also found at the individual level.11 Given that connection, it is interesting to discover how Chinese peasants feel about the on-going market-driven reforms which started in the late 1970s and whether their views on the free-market economy affect their belief in democratic values. It is thus hypothesized that individual peasants in southern Jiangsu province who embraced market-driven reform and private ownership were more likely to support core democratic values.

It is apparent that the economic reforms that began in the late 1970s have dramatically changed the face of China, making it one of the fastest growing economies in the world. These reforms have markedly improved the standard of living for ordinary Chinese people. Yet, these reforms have also had negative consequences such as inflation, declining social welfare programs, corruption, a widening gap between rich and poor, and job insecurity. In the two surveys conducted in Beijing in the 1990s, there was lukewarm support for the adoption of a complete or predominantly market economy.12 Although these economic reforms started in the countryside and received strong initial support from the peasantry who benefited from them, since the late 1980s the economic situation in rural China has deteriorated and the income gap between urban residents and peasants has widened due to declining prices for agricultural products, the rising cost of farming, and excessive fee collection by local governments. Given the new peasants’ current circumstances, do Chinese peasants still support free market-driven reforms?

The results for the questions about preferences for economic systems and ownership structures show an interesting pattern. With regard to economic systems, very few respondents preferred a totally central planned economy (CPE) or a predominantly CPE (see Table 2.5). Also not many people (only 9.8 percent) preferred a genuinely mixed economy. Compared to data from the Beijing surveys, these figures are much lower. Around 56 percent of the respondents preferred either a mostly market economy or a total market economy. This figure is much higher than that in the Beijing surveys. A quarter of the respondents in the rural Jiangsu survey had a hard time deciding which system would be best for them. It seems that a market economy, which has been favored and promoted by the government since the early 1980s, is more acceptable to the peasants in Jiangsu than urban residents in Beijing. This is probably because urban residents have been more affected negatively than peasants by the market-driven reforms that have led to redundancies from state-owned enterprises. Also Chinese peasants are more economically independent and do not receive much in the way of state welfare and subsidies.

Table 2.5 Attitudes toward economic reforms (%)

Note

* Figures in parentheses are combined findings from surveys conducted in Beijing in 1995 and 1997.

Source: Jiangsu Rural Survey 2000

When it comes to forms of ownership of the means of production, most of the peasants in the survey still preferred predominantly public owned, even though the figure is lower than that in the Beijing surveys. Close to 15 percent of the Jiangsu peasants in the survey supported an evenly mixed ownership system, with very few favoring totally private ownership. The support for a predominantly publicly owned system among our respondents may be explained by two factors. The first is the official policy of maintaining just such a system in the economy even though private business (including foreign investment) has made tremendous strides and has been playing an increasingly important role in the Chinese economy in the past three decades. The second is the predominant position of collectively owned TVEs that existed in Jiangsu at the time of the survey. Before 2000, southern Jiangsu was well known for its successful collective TVEs which were referred to as the ‘Sunan model’ of rural economic development in China.

When asked about the pace of economic reforms, close to 40 percent of the respondents seemed satisfied with the current pace. However, around 20 percent thought they had been moving fast (17.6 percent) or too fast (2.2 percent). Interestingly, about an equal number of the respondents believed the economic reforms had been moving either slow (14.7 percent) or too slow (5.6 percent). Again, these last two figures are higher than those in the Beijing surveys, suggesting peasants in our Jiangsu survey are more reform-minded than the urban residents in Beijing. Once again, around 20 percent of the respondents had difficulty in answering the question. These findings show that there is no consensus concerning the pace of economic reform even though most people seemed content with the current pace. Answers to these questions were tallied and added to form an additive index to be used as the independent variable of support for market-driven economic reform in the multivariate analysis.

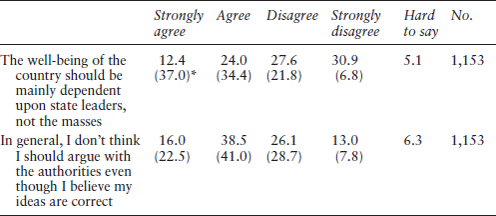

Political efficacy

According to Angus Campbell, Gerald Gurin, and Warren Miller, political efficacy is ‘the feeling that individual political action does have, or can have, an impact upon the political process’.13 Democratic values are all about public participation in the decision-making process and belief that individual citizens can have an influence and impact upon politics. Therefore, it is hypothesized that those who had higher degrees of confidence in their ability to influence politics (that is, higher degrees of political efficacy) in rural southern Jiangsu province also tended to support core democratic values more than those who did not. To measure the level of political efficacy, the respondents were asked to assess two statements: (a) ‘The well-being of the country is mainly dependent upon state leaders, not the masses’ and (b) ‘In general, I don't think I should argue with the authorities even though I believe my ideas are correct’. The findings were mixed. Close to 60 percent of the respondents believed that the well-being of the country should depend on the masses instead of state leaders (see Table 2.6). The number is actually higher than that obtained in the Beijing surveys. However, most people in southern Jiangsu province (about 55 percent) were reluctant to challenge the authorities (compared to 63 percent in the Beijing surveys). A summary variable of political efficacy is derived from the respondents’ sum of the scores on both statements and used as the independent variable in the multivariate analysis.

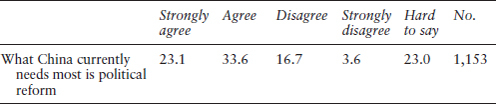

Support for Political Reform

China has made great strides in economic reforms since the late 1970s. Yet it has made little progress in meaningful political reform. However, it is erroneous to say that China has not engaged in political reform at all since Mao's death. Rather, the emphasis of Chinese political reform has been more on political rationalization and legalization.14 Specifically the post-Mao leaders abandoned Mao's practice of class struggle and continuous revolution, rebuilt the party and governmental apparatus with the aim of improving bureaucratic efficiency. However, post-Mao leaders, such as Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, and Hu Jintao, have yet to decide to adopt fundamental and systematic political reforms. Political reform is understood as further liberalization and democratization of the Chinese political structure as it would make the decision-making process more transparent and hold up public officials to public scrutiny. It is therefore hypothesized that peasants in southern Jiangsu province survey who favored political reform were more likely to support core democratic values. The statement used in the survey to measure support for political reform is fairly straightforward. Respondents were asked to agree or disagree with the statement ‘What China needs most is political reform’. Table 2.7 shows over 55 percent of them agreed or strongly agreed. The scores for individual respondents are used as the independent variable for support for political reform in the multivariate analysis.

Table 2.6 Levels of political efficacy (%)

Note

*Figures in parentheses are combined findings from survey conducted in Beijing in 1995.

Source: Jiangsu Rural Survey 2000

Table 2.7 Support for political reform (%)

Source: Jiangsu Rural Survey 2000

Key socio-demographic variables

There is a widespread theoretical consensus linking key demographic factors with support of democratic values. Drawing upon previous studies, it is expected that demographic factors influenced the respondents’ attitudes toward democratic norms. Specifically, the focus is on the impact of age, education, and gender on the support of core democratic values.

Age

In their study Finifter and Mickiewicz found stronger support for democratization among young people in the former Soviet Union.15 They credited this phenomenon to the fact that the youth in the former Soviet Union tended to be associated with ‘modern’ ideas and were more open-minded than older people. Similar findings were also claimed in China.16 For example, Chan and Nesbitt-Larking argued that youth in China tended to be more critical of the government and more protective of their individual rights.17 Based on these observations it is hypothesized that younger peasants in southern Jiangsu province would be more supportive of core democratic values and norms.

Education

Education has long been used as a predictor of people's political attitudes. In their seminal work The Civic Culture, Almond and Verba conclude that ‘educational attainment appears to have the most important demographic effect on political attitudes’ and that the more educated one is, the more he or she is inclined to possess ‘civic culture’.18 Other scholars have in particular argued that regardless of official ideological norms, education contributes to the support of democratic values because ‘education broadens perspectives, increases stores of information, and … contributes to respect for diversity and difference’.19 Intellectuals and students always stood at the forefront of liberal and democratic movements in China in the twentieth century. A survey conducted in 1990 in China also shows that education had a positive impact on political tolerance.20 Thus, it is expected that higher levels of education among peasants in southern Jiangsu province led to stronger support for core democratic values and norms.

Gender

Although sexual equality has been officially promoted in China since 1949, women in China have never achieved equal status with men. In fact, women's social status has arguably declined in the reform era due to market-oriented reforms. Chinese authorities are very ineffective in enforcing gender equality laws and employers openly discriminate against women in the job market due to perceived ‘women problems’. As a result, women are often given only traditional jobs such as secretaries, waitresses, teachers, and nurses. The social status of women in the Chinese countryside is even worse than that in the urban areas. Most women in rural China stay at home and play the traditional roles of mothers and wives.21 It is reasonable to assume that Chinese women tend to be more traditional in values and culture and are more obedient to authorities. Evidence from the former Soviet Union suggests that there is a connection between gender and attitudes toward democratic values and democratization.22 Specifically, women were found to be less supportive of democratic values because of their female traditional roles in society.23 Therefore, it is hypothesized that female respondents in our survey were less supportive of core democratic values than men.

Multivariate analysis

Table 2.8 presents the multivariate analysis (ordinary least squares multiple regression) results in support of core democratic values in the Jiangsu survey. Altogether, the two categories of independent variables (socio-economic: satisfaction, income, political satisfaction, support for a free market economy, political efficacy, support for political reform; demographic: age, education, and gender) explain 13 percent of the variance in support of core democratic values and norms.

Earlier it was hypothesized that people who were more satisfied with their socio-economic conditions were less likely to support core democratic values since the realization of these values would lead to major changes to the current Chinese political system. The findings from our multivariate analysis, however, reject this hypothesis. In fact, it shows that people who felt that their socio-economic conditions had improved were more supportive of core democratic values. In addition, levels of income are also positively related to the support of democratic values even though the association is not statistically significant. It seems that improvement in people's material and social life has not reduced their desire for democracy. It should be pointed out that this finding is in accordance with the generally held proposition that improvements in living conditions or material life facilitate democratization.24 This proposition has also been proven by evidence from the past three decades.25

Table 2.8 Multiple regression in support of core democratic values

Independent variables |

Support for core democratic values |

|

Non-standardized coefficient |

Standard error |

|

Socio-economic satisfaction |

0.132** |

0.047 |

Income |

0.019 |

0.021 |

Political satisfaction |

–0.092* |

0.040 |

Support for market reform |

0.323** |

0.063 |

Political efficacy |

0.115** |

0.041 |

Support for political reform |

0.714** |

0.078 |

Demographic attributes |

||

Age |

–0.499** |

0.187 |

Education |

0.147* |

0.074 |

Gender (female = 0; male = 1) |

0.302** |

0.112 |

Constant |

23.621** |

0.939 |

Multiple R |

0.364 |

|

R2 |

0.132 |

|

Adjusted R2 |

0.125 |

|

Note

Abraham Maslow's theory of a ‘hierarchy of needs’ is often cited to explain the positive relationship between life improvement and a desire for democracy and liberties. As Larry Diamond notes, ‘While the satisfaction of lower-order needs does not automatically increase the salience of individual needs for political freedom and influence, it makes the valuing of those needs more likely’.26 This finding has pointed out a brighter future for democratization in China since economic reforms are continuing to improve people's material life and living conditions.

Table 2.8 also shows that people in the survey who were less satisfied politically tended to be more supportive of democratic values and norms. Political satisfaction here is measured primarily in terms of satisfaction with clean government. There is no doubt that corruption is a serious problem in China and is one of the key issues that concern people. The negative relationship between political satisfaction and support for democratic values and norms suggests that people expect to use democracy to eliminate or lessen the problem of official corruption.

It was also hypothesized that people who supported a market economy were more likely to support core democratic values. This is confirmed by the multivariate analysis (see Table 2.8). This result puts into question the theory of ‘neo-authoritarianism’, which advocates a transition to a market economy while withholding democratic reforms. It also confirms that there is a positive relationship between a market economy and democratic values and system, as argued by scholars such as Schumpeter and Dahl.27 In the current Chinese context, both marketization and democratization involve shifting power from the state to individuals. This positive relationship points to good prospects for democratization in China since the market-driven reforms are still continuing and may facilitate the democratization process. Thus it is expected that further market reforms will contribute only positively to the establishment of a more democratic system in China.

The multivariate analysis also indicates, not surprisingly, that people who had higher levels of political efficacy were more likely to support core democratic values. In addition, Table 2.8 shows that the perceived need for political reform is positively related to support for core democratic values, as was hypothesized earlier. Thus, people who desired political change were likely to support potential democratization in China. In particular, the types of political reform that our respondents look for are more freedom of press, meaningful and competitive elections and equal protection of rights for all citizens regardless of their political views.

Finally, all the three key demographic factors in our study are strongly related to the support of democratic values. Our multivariate analysis shows that young people, men and people with a better education tended to be more supportive of core democratic values and norms. These findings are in accordance with empirical evidence discovered in other countries. The results for age and education point to positive prospects for democratic changes in China, since the future belongs to the young and Chinese educational levels are improving.

Conclusion

Traditionally the Chinese peasantry has been blamed for not having any interest in democracy. It has been seen to be backward in culture and political orientation, lacking education, and naturally obedient to authorities. The findings from survey data collected in southern Jiangsu province, however, contradict these conventional wisdoms. As southern Jiangsu province is one of the most economically developed rural areas in China, the author does not want to infer that the descriptive findings in this chapter hold true for the rest of the Chinese countryside. However, the multivariate analysis carried out here could be generalized to the whole country because the analyses were done at an individual level.

Descriptive data from this survey show that the peasants in southern Jiangsu province had relatively high levels of democratic values and political efficacy. They overwhelmingly endorsed elections as the means of official promotions and appointments, were extremely supportive of freedom of the press, and showed relatively high levels of political tolerance. The findings also show that rural respondents in southern Jiangsu had higher levels of democratic culture than the urban respondents in the Beijing surveys conducted in the 1990s. In addition, they indicate high levels of socio-economic satisfaction in the reform era. Yet most of our respondents were not happy with the corruption situation in their local area and they demanded more political reforms. While it may be premature and incorrect to say that all Chinese peasants are ready for democracy, it does seem that rural residents in southern Jiangsu are quite ready for democratic change.

On the economic front, the government's efforts to develop a market economy while maintaining a primarily public ownership system seem to enjoy a high degree of support among the peasants in southern Jiangsu. In fact, more people in our Jiangsu rural survey supported a market economy than in the Beijing surveys. This is probably due to the fact that market reforms in the rural area (such as de-communization) occurred fairly early in the reform era (in the late 1970s and early 1980s) and there are no state-owned enterprises in rural China.

The multivariate analysis is even more revealing. First, improvement in socio-economic conditions has not prevented people from believing in democratic values and norms. The better people are satisfied with their socio-economic life, the more they tend to be supportive of core democratic values and norms. Second, higher levels of political efficacy, lower levels of political satisfaction, and free-market values are conducive to democratic values among Jiangsu peasants. In addition, a perceived need for political reform contributes positively to support for democratic values. Third, young people, men and peasants with higher educational levels tend to be more in favor of democratic values and norms.

Overall, these findings point to a brighter future of democratization in the Chinese countryside. Over the past decade there has been a general and steady deterioration of stability in the Chinese rural areas due to a combination of factors such as misbehavior and corruption by the local government officials, misguided government policies, and a lack of improvement in peasant living conditions. Peasant riots and disturbances are not uncommon in modern China. The stability and economic development of China depend much on the situation in the vast rural areas. How to accommodate the political demands of the peasants while maintaining a steady economic growth is still an enormous challenge for the Chinese government. Realizing that democracy can be an effective means to solve, in part, China's rural problems, the Chinese government has started experimenting with democratic practices in rural areas. (Chapter 6 will focus on village elections in China.) It remains to be seen how far the democratic practices will go.