Chapter 9

Trustees’ Non-Fiduciary Duties and Powers

Chapter Contents

Fiduciary Duties, Non-Fiduciary Duties and Powers

Duty of Care and Skill Required of a Trustee

Chapter 8 introduced the trustee: How a trustee may be appointed and how their trusteeship may be ended. This chapter builds upon Chapter 8 and moves forward to address a trustee’s non-fiduciary duties. It also considers the powers that a trustee enjoys in administering the trust.

As You Read

Look out for the following:

![]() the types of non-fiduciary duties that a trustee is subject to;

the types of non-fiduciary duties that a trustee is subject to;

![]() the types of power that a trustee enjoys; and

the types of power that a trustee enjoys; and

![]() the standard of care and skill that a trustee should use when exercising his duties and powers.

the standard of care and skill that a trustee should use when exercising his duties and powers.

Fiduciary Duties, Non-Fiduciary Duties and Powers

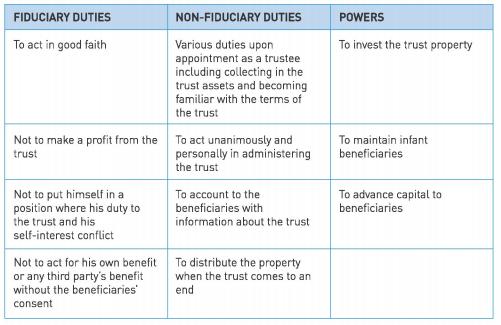

As was seen in Chapter 8, a trustee is a type of fiduciary who is subject to a number of duties of both a fiduciary and non-fiduciary nature. The trustee also possesses a number of powers. As a reminder, these duties and powers are set out in the table in Figure 9.1.

Non-Fiduciary Duties

Breach of a non-fiduciary duty generally means that the trustee will be liable to pay equitable compensation to the trust for the loss it has sustained. Of course, the trustee will only be liable

to pay compensation providing a true loss can be shown1 to have been sustained by the trust and the trustee’s liability for such loss has not been successfully excluded or limited by a trustee exemption clause. Both of these issues are considered further in Chapter 12.

Duties upon appointment as a truste

The trustee is subject to various duties when he is appointed to be a trustee. These duties were outlined by Kekewich J in Hallows v Lloyd.2 He said that the trustees must:

![]() ascertain what the trust property is;

ascertain what the trust property is;

![]() ascertain the terms of the trust which they are required to administer; and

ascertain the terms of the trust which they are required to administer; and

![]() read the trust documents to see what, if any, incumbrances affect the trust.

read the trust documents to see what, if any, incumbrances affect the trust.

Kekewich J’s comments are logical. The trustee’s duties should, as a matter of basic principle, include understanding the terms of the trust which he is bound to administer. This will include making himself familiar with the beneficiaries and the terms of the trust and seeing what, if any, specific duties the settlor has placed upon him and what powers he enjoys. The trustee must also ascertain what incumbrances (obligations) bind the trust so that he can comply with them.

The trustee must own an interest in the trust property if he is to administer the trust. The settlor must, consequently, constitute the trust.3 Provided a deed has been used to appoint him, s 40 of the Trustee Act 1925 provides that the trust property will be vested in the trustee automatically upon his appointment.

The additional duty of the trustee to collect in the trust assets if he is not appointed by deed — forcefully if necessary — was spelt out by the Court of Appeal in Re Brogden.4

The facts concerned trusts established by John Brogden. He left £10,000 in his will to each of his two daughters and one of his sons. During his life, he worked in partnership with his three sons in a colliery business. After his death, one of his daughters, Mary Jane Billing, wanted her share of the money to be appropriated to her benefit under the trust. The trustee was reluctant to do so as to do so would have resulted in the trustee obtaining the money from the business which Mr Brogden’s three sons continued to run. In correspondence with Mary, the trustee thought to press for the money would have put him ‘in a very unpleasant position with your brothers’. Ultimately, the colliery business became insolvent. The issue for the Court of Appeal was what, if any, liability was to be borne by the trustee for not pressing for the money to be transferred to the trust.

Cotton LJ believed that the trustee’s duty was to demand the payment of the money due to the trust and, if the money was not paid by the business, to take ‘reasonable means’5 to enforce the payment. The trustee should have acted far more forcefully than he did. If needed, he should have taken legal action against the business to recover the money for the trust. His action fell far short of this. He did not demand the payment due and was willing to enter into negotiations with the partnership over what types of assets the business would give to the trust to satisfy the debt owed to the trust. Consequently, the trustee was personally responsible for the loss to the trust fund. Only if the trustee could show that the trust would not have recovered the money from the business could he be excused from liability. The trustee could not show that here.

The case illustrates that the duty of the trustee upon taking office is to secure the trust assets, taking legal action if necessary. It also shows the serious consequence for the trustee if such assets are not secured: the trustee will have to make good the loss to the trust from his own personal assets. Fry LJ described the trustee’s duty as ‘the duty — the dominant duty, the guiding duty — of recovering, securing, and duly applying the trust fund’.6

Breach of the duty does not depend on the trustee acting with bad faith or dishonestly. On the contrary, the Court of Appeal accepted that the trustee had behaved honourably throughout. That was irrelevant, however. The task for the trustee was to collect in the trust assets which he had failed to do.

Duty to act unanimously and personally

At common law, the trustee was obliged to administer the trust personally. In the case of more than one trustee, this means that all of the trustees have to become involved in the administration of the trust. As Cross J pointed out in Re LuckingsWill Trusts,7 a passive trustee will be responsible for decisions which cause loss to the trust fund if he simply allows an active co-trustee to make decisions on his own. There is, therefore, a disincentive for a trustee to stand by and let his fellow trustees make decisions in administering the trust.

The liability of two or more trustees is joint and several.8

Glossary: Joint and several liability

Joint and several liability can only apply where two or more people are acting together. ‘Joint’ means that they are together responsible for their actions. ‘Several’, however, means their liability can attach just to one of them. For example, if two trustees breached a trust, it would be open to a beneficiary to take legal action against them both — for they are both jointly liable for the breach — or just one of them to recover the entire loss sustained by the trust.

Exceptions can occur when trustees do not have to act unanimously. One such exception concerns small charitable trusts (with an income of less than £10,000 in the previous financial year) where two-thirds of their trustees may decide under s 268 of the Charities Act 2011 to exercise a range of powers, for example, to transfer trust property to another charitable trust.

The duty to act personally was founded on the Latin maxim delegates non potest delegare — the person to whom something has been delegated cannot himself then delegate his task. The logic behind it is self-explanatory: the settlor has deliberately chosen someone to administer his trust and had he wanted the trustee to delegate their functions to another person, the settlor would have chosen that second person himself. This duty could be altered in the terms of the trust deed if the settlor so wished. But the duty of personal service had an exception, as Viscount Radcliffe explained in Pilkington v IRC,9 ‘[t]he law is not that trustees cannot delegate: it is that trustees cannot delegate unless they have authority to do so’.10

As trusts became ever more complex to manage and the types of investment grew wider in scope, trustees began to delegate their functions more and more, whilst remaining in overall charge of the trust.

The functions that a trustee may delegate

Trustees now enjoy a wide ability to delegate their powers. This ability is set out in Part IV of the Trustee Act 2000.

The Trustee Act 2000 greatly enhanced the trustee’s ability to delegate their functions. In non-charitable trusts, s 11(2) provides that a trustee may delegate any of their functions apart from what may be termed their ‘core’ duties. The functions that a trustee cannot delegate are those related to:

[a] whether and how the assets of the trust may be distributed;

[b] whether and how any payments owed by the trust should come out of capital or income funds;

[c] any power to appoint a new trustee; and

[d] any power that the trustee otherwise enjoys to delegate one of their functions.

The people to whom a trustee may delegate functions

Trustees may appoint agents, nominees and custodians to whom they may delegate their functions.

Suppose Scott declares a trust appointing Thomas as his trustee. The trust property is £100,000. Thomas has no knowledge of investment opportunities that may exist and realises he needs some assistance in deciding what type of investments to make.

Thomas can appoint an agent to advise him what type of investment to make. An obvious example might be that if he decided that he wanted to invest in shares, he might appoint a stockbroker to advise him which companies were performing well and worthy of investment. He might instruct the stockbroker to buy shares suitable for the trust. If the stockbroker is appointed as an agent, the actual contract for the purchase of the shares is made between the trustee and the company selling the shares. The agent is not part of the transaction.

A nominee is a slightly different concept. A nominee is someone in whose name property might be registered, but who is not the true owner. Thomas might appoint a nominee if he wished to keep an investment secret from the outside world. Alternatively, nominees are often used to purchase shares in a speedy manner. It is quicker for the nominee to buy the shares in its name rather than advising the trustee to purchase shares for the trust and then waiting for that transaction to take place.

A custodian receives assets for safe-keeping. A trustee might decide to place trust assets into the hands of a custodian where they will remain until the trustee collects them. Custodians are often used by charities for them to retain the legal title to a charity’s property whilst the trustees administer the trust.

Under s 12 of the Trustee Act 2000, the trustees may appoint one of themselves to be an agent for the trust. A beneficiary cannot, however, be appointed as an agent.11 The trustees have the capacity to decide the terms of the agent’s appointment.12 Special rules exist under s 15 for agents appointed to exercise asset management functions. These include that the agreement under which such an agent is appointed must be in writing13 and the trustees must prepare a written policy statement guiding the agent as to how the trust assets should be managed.14 This statement must be kept under constant review.15

A nominee may be appointed by the trustees under s16 of the Trustee Act 2000. Such appointments must be in writing16 and can be in relation to any of the trust’s assets, except for settled land.

Trustees may also appoint a custodian of the trust’s assets under s 17 of the Trustee Act 2000. Such appointment must again be in writing.17 A custodian is defined in s 17(2) as:

For the purposes of this Act a person is a custodian in relation to assets if he undertakes the safe appointment of the assets or of any documents or records concerning the assets.

Under s 19 of the Trustee Act 2000, nominees and custodians must either be people who carry on businesses as professional nominees, or custodians, or a corporate body, which is controlled by the trustees. Provided this condition is met, agents, nominees and custodians can all be one and the same person.18 The trustees may decide the terms of appointment of any nominee or custodian.19

Steps that trustees must take when delegating their functions

(a) Choose prudently

Whoever the trustees choose, the trustees must exercise their choice prudently, as illustrated by Fry v Tapson.20 If they do not, they are liable for his errors.

Two trustees were appointed by the will of John Dunn to invest trust monies either by lending the money as mortgages over property in Tasmania or Great Britain or by investing the money in shares in public companies in the UK. The trustees decided to invest £5,000 by advancing it over a property in Liverpool. The money was to be secured by a mortgage, which was to earn the trust interest at 4.5 per cent. The solicitor of the trustees recommended a surveyor to value the property and the trustees accepted that recommendation. The problem was that the surveyor was based in London and there was no evidence that he even went to Liverpool to value the house. It was valued at £7,000-£8,000 and the mortgage was duly entered into.

The borrower failed to repay the mortgage and went bankrupt. Developments had taken place adjacent to the house which meant that its value had fallen and was worth less than the amount due under the mortgage (this is known as ‘negative equity’ although this has nothing to do with the courts of equity). One of the beneficiaries brought an action against the trustees for breach of trust. Evidence showed that the house, even when the mortgage was created, was worth barely enough to cover the amount advanced.

Kay J described the appointment of a London surveyor to value a property in Liverpool as a ‘most incautious act’.21 He had no local knowledge of either that particular house, or the general property market in Liverpool. His report was written to generate interest in the house. Kay J acknowledged that, if an agent was properly employed by a trustee, the trustee would not be responsible for the agent’s faults. But the agent was not properly employed here. He was employed ‘out of the ordinary scope of his business’22 as he was not familiar with the Liverpool property market. By failing to choose their agent prudently, the trustees were liable for his faults.

(b) Review performance

If an agent, nominee or custodian is appointed, the trustees’ task does not end upon that appointment. Section 22 of the Trustee Act 2000 makes it clear that the trustees must keep the appointment under constant review. Trustees must, if necessary, consider whether to intervene in the appointment and exercise any power that they may have.23 Section 22(4) specifies that an intervention may take the form of the trustees giving directions to their agent, nominee or custodian or even going so far as to revoke the appointment entirely. What is clear is that, once appointed, the trustees cannot sit back and let their appointee run the trust in their place. This was shown in Re Lucking’s Will Trust.24

Here, a trust was set up which consisted of a majority shareholding in Stephen Lucking Ltd, a small business which had a factory in Chester. Profits in the business were falling. The trustee (who was also a director of the company) appointed Mr Peter Dewar to be a director and the new manager of the business. The company had a bank account on which cheques could be drawn, but the cheques needed the signature of two directors. A practice developed whereby the trustee would sign blank cheques and send them to Peter for him to complete the amounts and also sign them. Peter lived in Scotland and had considerable commuting expenses, which he settled using the ‘blank cheque system’ of payment. Peter then borrowed money from the company without the trustee’s knowledge, simply recording the borrowing as a ‘loan to a director’. Whilst the trustee accepted Peter’s explanation for this, again the loan was facilitated using the blank cheque payment method. Over a few years, Peter’s indebtedness to the company increased to over £15,800. Peter went bankrupt, owing the company this money.

One of the beneficiaries brought an action against the trustee for failing to supervise Peter. She alleged that she had been caused a loss because the company had itself suffered a loss which could have been distributed to her as effectively a shareholder in the company.

Cross J held that the trustee was liable for breach of trust for part of the loss suffered by the trust. The trustee was not liable for breach of trust simply by signing blank cheques, even though such action was described by Cross J as inherently ‘notoriously dangerous’.25 Further, the trustee was not liable for the period of time that he had no reason to suspect Peter was abusing the confidence that the trustee had placed in him. This changed, however, when Peter began withdrawing excessive amounts from the company, in addition to his salary and expenses. At that point, the trustee should have noticed that Peter was abusing his position. The trustee would only have seen this if he had kept a closer eye on Peter’s dealings. Failure to do so meant that the trustee was liable for that loss sustained by the trust fund.

Duty to account to the beneficiaries with relevant information about the trust

It might be assumed that, because the beneficiaries have an interest in the trust property, they are entitled to be kept fully and entirely up-to-date with accurate information about the trust. For example, beneficiaries might wish to know how the trust property is being invested, how those investments are performing and to what extent any of their number has enjoyed any of the trust property.

Over the last century, the courts have narrowed the circumstances when beneficiaries are entitled to see information about the trust.

In O’Rourke v Darbishire,26 the House of Lords gave beneficiaries a wide entitlement to see information concerning the trust. The facts concerned a disputed winding up of the estate of Sir Joseph Whitworth. The claimant’s case was that he was entitled to part of the estate of Sir Joseph. To pursue his claim successfully, he needed to have sight of certain documents.

Lord Wrenbury agreed with the decisions of the Court of Appeal and the High Court in the case in that a beneficiary had a proprietary right to see trust documents, explaining, ‘[t]he beneficiary is entitled to see all trust documents because they are trust documents and because he is a beneficiary. They are in this sense his own’.27

A beneficiary did not need to take court action to enjoy this right. It was a proprietary right he enjoyed.

Lord Wrenbury said the beneficiary’s right was not to be confused with the legal process of discovery (now called ‘disclosure’). In a civil action, this is the stage of legal proceedings where each party reveals to the other relevant documents which either help or hinder their case.28 The beneficiary did not enjoy his right under this process as discovery was, and disclosure remains, the right to see another party’s documents. The beneficiary’s right was a proprietary one which he enjoyed as a beneficiary. It was entirely separate to this process.

On the facts of the case, the claimant was not a beneficiary and had, therefore, to establish an entitlement to see the disputed documents through the process of discovery. The claimant was partly successful in obtaining an order to see certain documents. What is important is that beneficiaries were recognised to have a proprietary right to have sight of all trust documents.

This issue was considered again by the Court of Appeal in Re Londonderry’s Settlement29 where its members curtailed a beneficiary’s right to see documents relating to the trust.

The facts concerned a discretionary trust of shares in Londonderry Collieries Ltd declared by the Seventh Marquess of Londonderry in 1934. The trustees, together with people referred to as ‘appointers’, were to decide who was to benefit from the defined class from the capital and income of the trust fund. One of the settlor’s daughters, Lady Helen Walsh, was a member of the class.

In 1962, the trustees decided to distribute the capital and thus bring the trust to an end. Lady Helen wanted more money than she had been given by the trustees. She asked the trustees to supply her with various documents but the trustees supplied only copies of documents detailing people whom they had chosen to benefit from the trust together with the trust’s annual accounts. Lady Helen’s motive in seeking these documents was to scrutinise the trustees’ reasons for preferring other beneficiaries over her. The trustees, to prevent family discord, decided not to supply any further documents detailing either the agendas or minutes of their meetings, or their correspondence with the appointers and other beneficiaries. The trustees brought an action for directions to the court, asking which documents they were bound to supply to Lady Helen.

In giving the leading judgment of the Court of Appeal, Harman LJ reminded the court that the trustees had never been under a duty to disclose to beneficiaries their reasons for reaching a decision over which they enjoyed a discretion. The reasoning behind this ensured trustees had some freedom to make decisions without their motives being called into question. If, however, trustees volunteered their reasons, whether or not they were sound could be questioned by the court.30

Harman LJ, with whom Danckwerts LJ agreed, thought that the observations of the House of Lords in O’Rourke v Darbishire over the right that a beneficiary had to inspect ‘trust documents’ were too general and provided little assistance to a beneficiary’s request to see specific documents. Harman LJ held that the minutes of the trustees’ meetings and the agendas prepared for such meetings were not documents that the beneficiary could inspect, because an inspection would immediately reveal the trustees’ motives and the reasons for their decisions. He did not believe that these documents could be described as ‘trust documents’. Even if they could, however, the beneficiary could not see them, because the principle that protected trustees’ deliberations on a matter of exercising their discretion could override the competing principle that the beneficiary was entitled to see all trust documents. The correspondence between the trustees, appointers and beneficiaries were not documents which a beneficiary enjoyed a right to inspect.

Salmon LJ agreed that as long as the trustees exercised their discretion honestly, their reasons for the exercise of that discretion could not be challenged. There was thus no point in disclosing trustees’ reasons to the beneficiaries — even if the reasons were disclosed, they were not open to challenge. Challenging trustees’ reasons would mean that trustees’ decisions would become impossible to make if they felt that such decisions were always open to be criticised in court.

Salmon LJ laid down the characteristics of ‘trust documents’:

Trust documents do … have these characteristics in common: (1) they are documents in the possession of the trustees as trustees; (2) they contain information about the trust which the beneficiaries are entitled to know; (3) the beneficiaries have a proprietary interest in the documents and, accordingly, are entitled to see them.31

He said that if any part of a document contained information which the beneficiaries were not entitled to know — such as trustees’ reasons for making a decision — then the document would not be one that the beneficiaries were entitled to see.

As well as providing information about what constituted a trust document, the decision in this case also placed limits on what beneficiaries were entitled to see. In particular, beneficiaries were not entitled to see the reasons for trustees’ decisions. This was either because, in Harman LJ’s view, non-disclosure of such reasons trumped the beneficiaries’ right to see the trust document or because the document containing the reasons was not a ‘trust document’ as defined by Salmon LJ.

The matter was addressed again in Schmidt v Rosewood Trust Ltd32 where a new approach to the issue of disclosure was given by the Privy Council.

The facts concerned two discretionary trusts, co-s et up by Vitali Schmidt, under the jurisdiction of the Isle of Man. His son, Vadim, as administrator for his father’s estate, brought an action to obtain accounts of the trusts and other information from the trustee, the defendant. As administrator for his father’s estate, the trustee had paid Vadim ![]() 14.6 million which the trustee said was his entitlement under the trusts. Vadim’s case was that his father had been entitled to a larger share of the total of

14.6 million which the trustee said was his entitlement under the trusts. Vadim’s case was that his father had been entitled to a larger share of the total of ![]() 105 million that constituted the trust fund. He wanted access to certain documents to assist his claim. The defendant’s defence, inter alia, was that neither Vitali nor Vadim were beneficiaries under either trust, but were mere objects of a power. As such, neither of them had any entitlement to see trust documents.

105 million that constituted the trust fund. He wanted access to certain documents to assist his claim. The defendant’s defence, inter alia, was that neither Vitali nor Vadim were beneficiaries under either trust, but were mere objects of a power. As such, neither of them had any entitlement to see trust documents.

In giving the opinion of the board, Lord Walker did not think that beneficiaries had an absolute proprietary right to see trust documents. Instead:

the more principled and correct approach is to regard the right to seek disclosure of trust documents as one aspect of the court’s inherent jurisdiction to supervise, and if necessary to intervene in, the administration of trusts.33

An applicant did not need a beneficial interest as such in the trust property to avail himself of such a right as ‘[t]he object of a discretion (including a mere power) may also be entitled to protection from a court of equity’.34 Such protection would depend on the court’s discretion to intervene in the administration of a trust.

In exercising that discretion, Lord Walker said that there were three areas which the court would have to consider:

[a] whether a beneficiary (or other applicant, such as an object under a power) should be assisted by the court;

[b] the types of documents which should be disclosed to the applicant and whether they should be disclosed in an edited or unedited form; and

[c] whether any safeguards should be imposed to restrict the use of the disclosed documents (e.g. by stating that the documents could only be inspected at a solicitor’s offices).

The tide in favour of beneficiaries had turned since O’Rourke v Darbishire as Lord Walker stated:

the recent cases also confirm … that no beneficiary … has any entitlement as of right to disclosure of anything which can plausibly be described as a trust document. Especially when there are issues as to personal or commercial confidentiality, the court may have to balance the competing interests of different beneficiaries, the trustees themselves, and third parties. Disclosure may have to be limited and safeguards may have to be put in place.35

On the facts, Vadim’s case was remitted to the High Court in the Isle of Man for determination as to whether he could seek disclosure of documents related to the trust. Lord Walker thought that Vadim’s claims were potentially sound and was therefore entitled to the disclosure that he sought.

Lord Walker thought that the three judgments of the Court of Appeal in Re Londonderry’s Settlement were not easy to reconcile. Harman and Danckwerts LJJ had treated the beneficiary’s right to see trust documents as a qualified right, which could be overridden by the competing principle that a trustee’s reasons should be kept confidential. Salmon LJ had preferred to try to define what could and could not amount to a ‘trust document’.

Do you think there is any discernible common thread running through these separate judgments?

Is a wish letter to be treated differently from other documents?

This question concerned the High Court in the more recent case of Breakspear v Ackland.36

The facts concerned three potential beneficiaries’ application for a wish letter to be disclosed to them.

Glossary: A wish letter

A ‘wish letter’ — or, sometimes, a ‘letter of wishes’ — is a document in which a settlor expresses a desire to the trustees to use their powers in a particular way.

Perhaps the most common use for a wish letter is with a discretionary trust. This is where the settlor initially establishes the trust for the benefit of a defined class. That class might be fairly large. The settlor might then attempt to narrow down the field in the class by expressing a wish to his trustees that certain people in the class be chosen as beneficiaries.

Wish letters are not binding on trustees. Yet often, out of courtesy, the trustees will take into account the people the settlor has set out in his wish letter.

Briggs J recognised that the use of a wish letter had two competing interests behind it. On the one hand, a wish letter was a useful device whereby a settlor could communicate sensitive and secret information to his trustees. It was therefore useful if such letters could be seen to be confidential and not subject to disclosure to beneficiaries. On the other hand, as in this case, the sight of a wish letter would often give the potential beneficiaries a solid idea of whether they were likely to benefit from the trust and would therefore prove invaluable to them in planning their lives and those of their children and dependants. Such competing interests had to be balanced by the court.

Briggs J referred to what he described as the ‘Londonderry principle’:

the process of the exercise of discretionary dispositive powers by trustees is inher-ently confidential, and that this confidentiality exists for the benefit of beneficiaries rather than merely for the protection of the trustees.37

He did not believe the decisions in Re Londonderry’s Settlement and Schmidt v Rosewood Trust Ltd conflicted. The cases were not on all fours with each other. Re Londonderry’s Settlement concerned documents that had a confidential nature about them. Schmidt v Rosewood Trust Ltd did not. The issue in that case was whether the applicant was entitled to see the documents, not whether the documents themselves were confidential or not.

After a thorough review of English, Australian and Channel Islands authorities, Briggs J held that the conclusion nowadays was not that the beneficiaries enjoyed any proprietary right to see trust documents but instead any request for the disclosure of a document possessed by the trustees was a request to the court to exercise its discretion. Bound by precedent, he followed the Londonderry principle. He also agreed with the reasoning behind it — that beneficiaries might in fact be protected by not having certain documents disclosed to them. Documents passing between a trustee and a settlor over which beneficiary should be chosen to benefit from a discretionary trust might, for example, reveal that one particular beneficiary was suffering from a life-threatening illness. Trustees had to have the security that their enquiries as to such matters could be kept confidential.

A wish letter in a family trust was written ‘for the sole purpose of serving and facilitating an inherently confidential process’.38 It was therefore appropriate that such a document should, prima facie, be seen to be confidential as between the settlor and trustees and not be disclosed to the beneficiaries. This confidence could be voluntarily overridden by the trustees but Briggs J thought that the trustees should only disclose a wish letter if ‘disclosure is in the sound administration of the trust, and the discharge of their powers and discretions’.39

Briggs J gave guidance for how trustees should manage a beneficiary’s request to them to disclose a wish letter in relation to family discretionary trusts. The trustees are obliged to consider whether they should exercise their discretion to allow the beneficiary sight of the document. The trustees may simply answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the beneficiary’s request and do not have to provide reasons for their decision. Providing reasons is, in some ways, more dangerous for the trustees, as the court can consider whether their reasons are honest.

The trustees may seek the court’s assistance as to whether they should disclose the wish letter. In such a case, the court itself had to have full disclosure of the letter. If disclosure was ordered, Briggs J thought that the safeguards mentioned by Lord Walker in Schmidt v Rosewood Trust Ltd could be employed. Briggs J thought that, as a matter of policy, the courts were not biased towards disclosure.

On the facts, Briggs J held that the wish letter had to be disclosed. That was due to the trustees’ intention to seek the court’s later sanction to their proposed distribution scheme of the trust fund. At that later stage, the contents of the wish letter would be relevant to the proposed distribution and the potential beneficiaries had to be permitted to comment on the scheme. All disclosure of the wish letter would do at this stage would be to give that information to the potential beneficiaries at an earlier stage. Their right to comment on the proposed distribution scheme outweighed any family disharmony that might be suffered due to the disclosure of the wish letter.

Summary of the duty to account

The decision in Breakspear v Ackland is an interesting one. Aside from precedent considerations, Briggs J made it clear that he would have followed Re Londonderry’s Settlement in any event, over Schmidt v Rosewood Trust. It seems that he followed the views of Harman and Danckwerts LJJ in Re Londonderry’s Settlement and it is their views that he termed ‘the Londonderry principle’. In general, it seems clear that the beneficiaries no longer enjoy a proprietary right to see any trust document that they might wish to see. Certain documents which contain trustees’ reasons or other confi-dential information may be protected from disclosure. The trustees themselves may always override this by deciding voluntarily to disclose the document. If not, the actual (or potential, in the case of a discretionary trust) beneficiary may ask the court to order disclosure. The Londonderry principle — that trustees exercising their discretion to dispose of the trust fund is a confidential process and can override a beneficiary’s desire to see a document — remains good law. The court must balance the beneficiaries’ desire to see confidential documents with the need to allow trustees the ability to make decisions without fear of being impeached. If a document was ordered to be disclosed, then the safeguards suggested in Schmidt v Rosewood Trust Ltd could be employed.

Duty to distribute the trust fund

When the trust comes to an end, perhaps because the beneficiary has fulfilled the contingency, or a life tenant has died to be succeeded by the remainderman, the duty of the trustees is to pay the fund to the beneficiaries.

The trustees must ensure that they pay the money to the correct beneficiaries. This did not occur in Eaves v Hickson40 albeit the trustees were perhaps more unfortunate than deliberately neglectful or dishonest.

Mary Babinton left realty to her two trustees on trust to be divided into two halves: one half was for John Knibb’s children and the other for the children of William Knibb. The trustees sold the property. William Knibb sent the trustees a marriage certificate, in which he claimed to have been married in 1826. He also sent in his children’s baptismal certificates, with dates following that year. In fact, the marriage took place in 1836, but the marriage certificate had been forged. William’s children were all illegitimate. The trustees, acting in good faith and relying on the marriage certificate, paid out the money to William’s children. The children of John Knibb discovered the marriage certificate was a forgery and brought an action for the money which had been wrongfully paid out of the trust fund to be replaced.

The Master of the Rolls held that the fund had to be replaced. Although he believed that it was a ‘very hard case on the trustees’,41 ultimately they had paid the money out wrongly. The loss had to be borne by the person who had paid out the money. On the facts, the court strived to ameliorate the position to the innocent trustees. The court ordered the children who had benefited from the money to repay it with interest, with any shortfall being made up by William Knibb, who must have known that the marriage certificate had been forged. If any further shortfall remained, the trustees had to make it good.

Normally, it will be apparent when the trust has come to an end because either a benefi-ciary will have clearly fulfilled a contingency or the life tenant will have died. The court has power, however, to order the trustees to distribute the trust fund. An order to distribute the trust fund was made by the High Court, in unusual circumstances, in Re Green’s Will Trusts.42

The facts concerned the will of Evelyne Green and her only son, Barry. Barry was a tail gunner in a bomber aircraft that left RAF Linton-on-Ouse in January 1943 on a mission to Berlin. Barry was never heard of again. Later in 1943, Evelyne saw a photograph of a man in a Swiss magazine whom she believed to be Barry. Both the Red Cross and the government could not confirm this to her and believed the photograph to be dubious. Evelyne wound up her son’s estate in 1948 but she continued to believe that he was alive. When writing her will in 1972, she left her estate to Barry. She gave him until 1 January 2020 to come forward to claim it. If he failed to do so, then after that date the money was to go to establishing a foundation to treat deprived animals. One of the issues for the court was whether Evelyne’s estate should be distributed to the foundation or whether it should remain in trust pending Barry coming forward to claim it.

Nourse J held that Barry must have been presumed to have died on the night of the bombing raid, given that nothing further had been seen or heard of any of the crew members of that mission. An order would be made that the trustees must distribute the trust fund in favour of the charitable foundation that Evelyne had established in her will.

Nourse J made what is known as a Benjamin order. This originates from the case of Re Benjamin,43 in which the testator left his residuary estate in his will on trust for his 13 children. One of his sons had last been seen 10 months before the testator died in Aix-ia-Chapelle, France, allegedly making his way to London. Nothing had been seen or heard of the son since that time. The High Court made an order permitting the trustees of the testator’s will to distribute the estate of the testator as though the son had predeceased his father. This meant that the estate would be distributed amongst the other 12 children. Joyce J said the burden of proof of establishing that the son had survived his father was on those claiming under the son. They had failed to satisfy this burden.

Nourse J described a Benjamin order as one that:

does not vary or destroy beneficial interests. It merely enables trust property to be distributed in accordance with the practical probabilities, and it must be open to the court to take a view of those probabilities entirely different from that entertained by the testator.44

As to whether further time should elapse before the trustees should distribute the fund, Nourse J said that the test to be applied was:

whether in all the circumstances the trustees ought to be allowed to distribute and the beneficiaries to enjoy their apparent interests now rather than later.45

The case illustrates that a court can order the trust fund to be distributed, by making use of a Benjamin order. Such an order is a useful way of administering trusts which might otherwise, subject to the perpetuity period, remain in suspense for potentially a long period of time. It enables the trustees to carry on their trusteeship by distributing the trust property.

A statutory mechanism exists in s 27 of the Trustee Act 1925 for the trustees to distribute trust property to beneficiaries of whom they have notice. This section provides that trustees can place an announcement in the London Gazette and in a newspaper local to the area connected to the trust giving notice that they intend to distribute the trust fund to all those beneficiaries of whom they have notice. The announcements must set out a period (not less than two months) in which beneficiaries can notify the trustees of their claim to the trust fund. If any genuine claims are made during that time period, those ‘new’ beneficiaries will obviously benefit from the trust. If, on the other hand, the trustees receive no claims, they can simply distribute the trust fund to all those beneficiaries of whom they have notice.

Making connections

Reflect now on why certainty of object is vital to form a valid trust. The key principle of certainty of object was that beneficiaries had to be at least ascertainable. Hopefully, they will all have been ascertained by the trustees before the trust fund is distributed but if not, provided they are ascertainable, the trustees may benefit from either a Benjamin order or the mechanism in s 27 of the Trustee Act 1925 to distribute the trust fund.

If you have forgotten about certainty of objects, now might be a good time to refresh your memory of that part of Chapter 5.

As well as these non-fiduciary duties, which trustees must undertake, they also enjoy various powers, which they may or may not use at their discretion.

Trustees’ Powers

Trustees enjoy three key powers:

![]() a power to invest the trust property;

a power to invest the trust property;

![]() a power to maintain beneficiaries; and

a power to maintain beneficiaries; and

![]() a power to advance capital to the beneficiaries before they become entitled to it.

a power to advance capital to the beneficiaries before they become entitled to it.

Making connections

A certain type of power has already been discussed in Chapter 2: the power of appointment. This is a power that a donee/trustee has to choose who will benefit from the donor or settlor’s generosity. The powers considered here are of a different type: they are concerned with managing the trust as opposed to selecting who will benefit from it.

The key concept of any power, however, is that there is no obligation on the recipient to use it. The trustee always has the choice whether to use it or not. Failing to comply with a duty is more serious as a duty carries with it an obligation to do or not do an act.

A trustee cannot, however, refuse to consider whether to exercise a power. Such a refusal would undoubtedly be a breach of one of the core fiduciary duties to act in good faith in the beneficiaries’ best interests.

A power to invest the trust property

This is probably the most important of the trustees’ powers. If the central concept of a trust is to administer property on behalf of another, it is logical that administering that property will mean investing it to secure a return in either capital or income or both forms.

Somewhat surprisingly, it was not until the Trustee Act 2000 came into force that trustees were permitted to make a wide range of investments. The Trustee Investment Acts 1961 had limited the types of investments that trustees could invest in to low-risk securities, such as government bonds and shares in public limited companies with a solid history of producing good profits. The purpose was to reduce risk to beneficiaries, but restricting trustees’ investment choices meant that beneficiaries suffered as the low-risk securities tended to produce low returns.

Under the Trustee Investments Act 1961, trustees were encouraged to invest in UK Government bonds (also called ‘gilts’). These remain today one of the safest forms of investment. They work by a purchaser effectively lending the government the purchase price of the gilt for usually a fixed period of time, say five years. When that fixed time expires, the amount of the gilt purchase price is repaid by the government, together with interest.

Many trusts will continue to invest a certain proportion of their wealth into gilts because they are considered to be a secure form of investment. It is highly unlikely that the UK Government will not repay the purchase price of the gilt to the investor. As they are low-risk, they tend to have low rates of return and the interest paid on them is not very high. It makes comparatively little sense for trustees to invest huge amounts, when slightly riskier investments could produce a better rate of return.

Fortunately, s 3 of the Trustee Act 2000 widened a trustee’s investment powers considerably. Section 3(1) provides that:

Subject to the provisions of this Part, a trustee may make any kind of investment that he could make if he were absolutely entitled to the assets of the trust.

This is known as the trustees’ ‘general power of investment’.46 The general power applies to trusts created before or after the Trustee Act 200047 and dramatically simplifies the modern-day investment rules for trustees.

Section 3 of the Trustee Act 2000 gives the trustee very wide powers of investment. The restrictions of safe investments imposed by the Trustee Investments Act 1961 are consigned to history. Nowadays, trustees will wish to spread their risk when investing and do not wish to invest in just one or two types of investment.48 Investments might be in various types of property, providing the trust with both secure and riskier types of investment. A typical trust might therefore invest in some or all of the following:

![]() Bank accounts. Investing the money in a bank account should be a low-risk form of investment. Care should be taken as the UK Treasury will only (presently) guarantee to reimburse up to £85,000 invested in each financial institution. The return on the investment will be interest that the bank pays on the investment. There will be no capital growth on the investment. As such, unless the trust is for a very short duration, depositing large amounts of the trust fund in a bank account is probably not a sound investment strategy. This type of investment is useful if the trustees wish to access the money quickly and constantly, perhaps in fulfilling a decision they may have taken to use the trust fund to maintain an infant beneficiary under s 32 of the Trustee Act 1925;

Bank accounts. Investing the money in a bank account should be a low-risk form of investment. Care should be taken as the UK Treasury will only (presently) guarantee to reimburse up to £85,000 invested in each financial institution. The return on the investment will be interest that the bank pays on the investment. There will be no capital growth on the investment. As such, unless the trust is for a very short duration, depositing large amounts of the trust fund in a bank account is probably not a sound investment strategy. This type of investment is useful if the trustees wish to access the money quickly and constantly, perhaps in fulfilling a decision they may have taken to use the trust fund to maintain an infant beneficiary under s 32 of the Trustee Act 1925;

![]() Gilts. Although these tend to have a low rate of return, they are perhaps the most secure form of investment possible and therefore the risk to the trust fund of losing money is low;

Gilts. Although these tend to have a low rate of return, they are perhaps the most secure form of investment possible and therefore the risk to the trust fund of losing money is low;

![]() Shares. If a company makes a profit, it can declare that part of the profit is returned to each shareholder. This is known as a ‘dividend’ and is the income that shareholders receive from their investment in the company. If the company makes profits consistently, its shares will be in demand from other investors, so the capital value of the shares should rise. Shares in public limited companies (especially those in the largest 100 publicly quoted companies on the FTSE index) are generally low-risk,49 but again, produce a comparatively low rate of return in that dividends paid tend to be low as do the capital value increases of the shares. Shares in private limited companies in the UK or abroad are riskier, but might produce higher rates of return for the trust, as occurred in Boardman v Phipps.50

Shares. If a company makes a profit, it can declare that part of the profit is returned to each shareholder. This is known as a ‘dividend’ and is the income that shareholders receive from their investment in the company. If the company makes profits consistently, its shares will be in demand from other investors, so the capital value of the shares should rise. Shares in public limited companies (especially those in the largest 100 publicly quoted companies on the FTSE index) are generally low-risk,49 but again, produce a comparatively low rate of return in that dividends paid tend to be low as do the capital value increases of the shares. Shares in private limited companies in the UK or abroad are riskier, but might produce higher rates of return for the trust, as occurred in Boardman v Phipps.50

Investing in shares tends to be undertaken over a long period, say for a minimum of 10 years, so that fluctuations in a company’s fortunes can be ironed out over time. Trustees should therefore only invest in shares if the trust will last for at least such a period of time;

![]() Land. Section 3(3) of the Trustee Act 2000 states that the ‘general power of investment does not permit a trustee to make investments in land other than in loans secured on land’. It then refers the reader to section 8 of the Act. Section 8 specifically states that trustees may acquire either freehold or leasehold land in the UK for any of the following purposes:

Land. Section 3(3) of the Trustee Act 2000 states that the ‘general power of investment does not permit a trustee to make investments in land other than in loans secured on land’. It then refers the reader to section 8 of the Act. Section 8 specifically states that trustees may acquire either freehold or leasehold land in the UK for any of the following purposes:

– for an investment;

– to enable the beneficiary to occupy the land; or

– for any other reason.

Section 8(3) makes it clear that the trustee enjoys the powers of a person who owns the land absolutely.

‘Land’ as such is not defined in the Trustee Act 2000. The non-binding Explanatory Notes to the Act refer the reader to Schedule 1 to the Interpretation Act 1978.51 This states that ‘land’ includes:

building and other structures, land covered with water, and any estate, interest, easement, servitude, or right in or over land.

Unless land is acquired for a beneficiary to live on, the most popular form of investment for a trust fund will be for ‘loans secured on land’ - in other words, a mortgage. The trust is therefore permitted to advance money to a borrower so that the borrower can buy the land and then repay the mortgage to the trust. This will result in income generation for the trust, as the loan will usually be repaid with interest.

When making an investment, trustees must have regard to what s 4(1) of the Trustee Act 2000 describes as the ‘standard investment criteria’. These are set out in s 4(3) as:

[a] the suitability to the trust of investments of the same kind as any particular investment proposed to be made or retained and of that particular investment as an investment of that kind; and

[b] the need for diversification of investments of the trust, in so far as is appropriate to the circumstances of the trust.

The aims of the criteria are to make the trustees consider explicitly whether the particular type of investment under consideration is appropriate for this particular trust and for the trustees to spread the risk of their investments. They are obliged to keep their investments under review in accordance with the criteria under s 4(2). They should aim to balance investments which produce income generation and those which produce capital growth.52 In that way, they are generating a return for both life tenants and remaindermen beneficiaries.

To apply these principles, trustees should prepare a statement of investment setting out their investment guidelines before they make investments.

The trustees failed to comply with s 4(2) in Jeffery v Gretton.53 Here a house in Cowes, Isle of Wight, was left by Paula Beken on a trust declared in her will to benefit Keith Beken for life with remainder to her son and his two children. The house was potentially worth a substantial amount but was in a run-down condition. After Paula died in 2001, her will was varied by terminating Keith’s life interest and the house being vested in the three other beneficiaries.

The trustees set about repairing the house themselves. The repairs needed were substantial and took approximately six years to complete. The house was eventually sold in 2008. One of the three beneficiaries brought an action for breach of trust against the trustees. Part of the claim was that the trustees had failed to keep the investment under the trust under review. Had they done so, the beneficiary claimed that the house would have been sold shortly after Paula had died. Instead, the house had been retained for six years and the trust had been deprived of income from it being rented out whilst the repairs dragged on.

The High Court held that, on the facts, there was no loss to the trust fund due to the trustees’ actions of retaining the house for such a long period of time but that was largely due to luck: ‘it is a case of a thoughtless breach of trust that happens to have turned out well’.54 But the trustees had been guilty of breaching s 4(2). They had not taken proper advice on the implications of their repairing the property themselves and, as such, they were in breach of their duty to keep the investment under review.

Under s 5 of the Trustee Act 2000, before investing and when reviewing the investments, the trustees must obtain and consider ‘proper advice’ as to whether the investment meets the standard investment criteria. ‘Proper advice’ is defined as coming from a person whom the trustees reasonably believe is suitably qualified to give it, due to the advisor’s ‘ability in and practical experience of financial and other matters relating to the proposed investment’.55 The only exception to obtaining and considering such advice is if the trustees reasonably believe that ‘in all the circumstances it is unnecessary or inappropriate to do so’.56 The Explanatory Notes suggest that an example of such an occasion could be if the proposed investment is small in value, so that any cost incurred in obtaining professional advice would be disproportionate to the benefit gained in doing so.57

Suppose that Scott creates a trust of £1 million, appointing Thomas as his trustee.

The trust fund is comparatively large and Thomas understands the need for diversification of the investments. Thomas has decided that part of the trust fund should be invested in paintings by old masters, part in land and part in gilts. As a financial adviser himself, Thomas would probably not wish to take separate advice about the investment in gilts. He would, however, need to take proper advice for the other investments. A surveyor with knowledge of the local area would be someone capable of giving proper advice for the investment concerning land. An antiques expert in art would be appropriate for giving advice for the paintings.

Before the Trustee Act 2000 was enacted, it was usual for settlors to give wide express powers of investment to their trustees, due to the restrictions imposed upon them by the Trustee Investment Act 1961. Settlors may still give such powers to their trustees if they wish. Given the wide wording of s 3(1) of the Trustee Act 2000, such express powers are probably unnecessary today. If, however, an express power of investment is given, it is in addition to the general power of investment under s 3.58

From the Explanatory Notes to the Trustee Act 2000, it appears that trustees may now take ethical considerations into account when deciding the types of investment to make. Previously, it had appeared that such consideration had been frowned on by the courts, as Cowan v Scargill59 demonstrates.

The facts concerned a pension scheme established by the National Coal Board (NCB) to provide retirement benefits to mineworkers. The scheme had approximately £200 million to invest each year. The scheme was managed by 10 trustees: five were appointed by the NCB and the remainder by the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM).

A plan of investment was proposed by which some of the annual fund was to be invested in overseas investments and oil and gas. The five trustees appointed by the NUM refused to adopt the plan as it was against Union policy. Deadlock ensued between the trustees, with those appointed by the NCB wishing to press ahead with the investments. Those trustees sought directions from the High Court over whether the investments could go ahead.

Megarry V-C held that they could. He said the main duty of the trustees in terms of wielding their powers was to use them ‘in the best interests of the present and future beneficiaries of the trust, holding the scales impartially between different classes of beneficiaries’.60 The interests of the beneficiaries had to come first, before those of the trustees. As Megarry V-C said, the beneficiaries’ interests usually meant:

When the purpose of the trust is to provide financial benefits for the beneficiaries, as is usually the case, the best interests of the beneficiaries are normally their best financial interests.61

In deciding whether to invest, trustees had to set aside their ‘own personal interests and views’62 and press ahead with the investment, if it would make the best financial return for the beneficiaries. Megarry V-C held that the proposed investments by the NCB were in the best financial interests of the beneficiaries of the trust.

Megarry V-C did conceive of a ‘very rare’63 exception whereby an investment might not be made for ethical considerations. He gave the example of a trust where all the beneficiaries were adults who had strong moral views against alcohol, tobacco and ‘popular entertainment’. In such a case, he thought that it might not be for those beneficiaries’ benefit for their trust to make investments in such industries, even though they would generate larger returns than in other industries. The key concept was that the investment had to be made for the beneficiaries’ benefit. Whilst that normally meant their financial benefit, the ethical benefit of a particular investment not being made could outweigh their financial benefit, but only on very limited occasions when it appeared that all of the beneficiaries would not wish the investment to go ahead.

The concept of benefit was considered again by the High Court in Harries v The Church Commissioners for England.64

Here, Richard Harries, Bishop of Oxford together with two colleagues, brought an action to determine the extent to which the defendants should have regard to promoting the Christian faith and ethics through their investment policies. The claimants’ concern was that the defendants were too focused on realising the best financial returns on their investments, rather than giving weight to religious and ethical considerations when investing Church of England funds. The facts were slightly different from Cowan v Scargill as they concerned a charitable trust as opposed to a pension fund.

Nicholls V-C held that charitable trustees had to try to obtain ‘the maximum return, whether by way of income or capital growth, which is consistent with commercial prudence’.65 The reason for this was pragmatic: ‘[m]ost charities need money; and the more of it there is available, the more the trustees can seek to accomplish’.66

Once again, therefore, trustees had to set aside questions of ethical consideration as the best interests of the charity meant they should make investments which gave the best return, taking into account diversification of investment and the need to balance income generation and capital growth.

Making investments on the basis of ethical principles was a difficult task for trustees to undertake. Nicholls V-C pointed out that often there was no definitive right or wrong answer to many moral questions. Trustees might take into account beneficiaries’ moral objections against particular investments, but only if they were satisfied that not making particular investments would not result in serious financial disadvantage to the charity.

On the facts, the defendants did have an ethical investment policy. For example, investments were not permitted in companies whose main business was in arms dealing, alcohol or tobacco. Their policy excluded approximately 13 per cent of listed UK companies. If the claimants’ more restrictive ethical considerations were accepted, an additional 24 per cent of UK listed companies would join the list of banned investments. Such a policy would lead to less diversification of investments. The defendants’ existing investment policy was sufficiently sound that it did not need to be disturbed.

In summary, the trustees’ power of investment is to invest the trust funds for the benefit of the beneficiaries, balancing the needs of income generation for life tenants with capital growth for the remaindermen. The beneficiaries’ benefit will almost always mean their financial benefit. On occasion, financial benefit may be set aside where adult beneficiaries are all opposed to a particular investment or in the case of a charity, as Nicholls V-C suggested in Harries v The Church Commissioners of England, where a particular type of investment would conflict with the charity’s aims, such as where a charity for the relief of cancer does not wish to invest in a tobacco company. Ethical considerations may play a greater part in future investment strategies, as the Explanatory Notes to the Trustee Act 2000 state that ethical considerations may be taken into account as part of the standard investment criteria under s 4(3).67

Power to maintain a beneficiary

The settlor may grant the trustees an express power to maintain a beneficiary in the trust document itself.

In the absence of such an express power, there is also a statutory power to maintain infant beneficiaries contained in s 31 of the Trustee Act 1925. This power only arises providing that there are no prior interests to that of the infant beneficiary whom the trustees seek to maintain.68

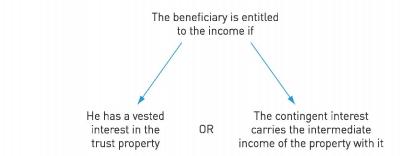

Section 31(1) provides that the trustees may pay money to the parent or guardian of the infant beneficiary for their ‘maintenance, education or benefit’.69 This money must be generated by the income from the investments. This means that the infant beneficiary must be entitled to the income from the investment. When a beneficiary will be entitled to the income from the trust fund is set out in Figure 9.2; this is when he either has a vested interest in the property, or alternatively, has a contingent interest which, according to s31(3), ‘carries the intermediate income of the property’.

The general principle is that those beneficiaries with a vested interest are entitled to the income from the trust property. They have no condition left to fulfil other than attain the age (18, nowadays) in which they may acquire the trust property absolutely. The issue is more controversial when concerned with contingent interests, which is where the beneficiary must fulfil a specific condition (for example, becoming a solicitor) before they are entitled to the trust property. The beneficiary might never meet the contingency so, at first glance, it is difficult to see why they should be entitled to the income from the trust property in the meantime.

The basic principle, then, is that only a beneficiary who enjoys a vested interest or a limited version of a contingent interest which carries with it the intermediate income (essentially, the interest generated by the money when it is invested) in the trust property may be maintained by the trustees from the income it generates.

If the trust is created by the settlor, inter vivos, the contingent interest will generally carry the intermediate income with it — in other words, the beneficiary will generally be entitled to enjoy the income from the trust property and the power exists, therefore, for the trustees to use it to maintain him.

The position if the trust is created in the testator’s will is more complicated. Statute provides that specific property — either realty or personalty — left to a beneficiary on trust will carry the intermediate income70 but a contingent gift of money (a legacy) will generally not unless it falls into one of the following categories:

[a] If the legacy is made by a parent or a person standing in the position of a parent (in loco parentis) to the beneficiary under s 31(3) of the Trustee Act 1925 the legacy is expressly said to carry the income with it;

[b] If the testator has shown an intention to maintain the beneficiary elsewhere, as occurred in Re Churchill.71 This case concerned the will of Louisa Churchill. She left £200 to her grand-nephew, Charles Plaskett, contingent upon him attaining 21 years of age. She gave a specific direction to her trustees that they could use the money to maintain him. The trustees sought directions from the High Court asking if interest was payable to Charles on his legacy.

Warrington J stated the general rule that the beneficiary should not become entitled to interest on the money until he attained a vested interest which in his case was when he attained 21. He acknowledged that there was an exception which allowed an infant to be maintained by interest payable on a contingent interest if the testator had shown an intention to maintain the beneficiary ‘as part of the testator’s bounty’.72 Louisa’s specific declaration that she permitted her trustees to maintain Charles demonstrated that she had showed an intention to maintain him and that the legacy should carry the interest which could also be used to maintain him as well as the actual gift itself; or

[c] If the testator has set the legacy aside specifically for the beneficiary, then it will carry the intermediate income with it. This occurred in Re Medlock.73 Here a testator left a legacy of £750 to his trustees on trust for the benefit of his grandchildren, providing they attained 21. If they did not, the money was to fall into his residuary estate, which he left to his wife for life. The court held that as the £750 was specifically set aside for the benefit of the grandchildren in the testator’s will, they were entitled to the interest from the money. That gift carried the intermediate income with it.

Providing the beneficiary enjoys either a vested or a contingent interest, which carries the intermediate income with it, the trustees may use the income from the trust property to maintain him. The trustees can decide to pay some or all of the income generated by the trust property. Section 31(1) provides that, in deciding whether or not to pay the money for the maintenance, education or benefit of the beneficiary, the trustees must take into account:

![]() the beneficiary’s age;

the beneficiary’s age;

![]() the beneficiary’s requirements;

the beneficiary’s requirements;

![]() the circumstances of the case;

the circumstances of the case;

![]() what (if any) other income is available to maintain, educate or benefit the beneficiary; and

what (if any) other income is available to maintain, educate or benefit the beneficiary; and

![]() where there is other income available, unless it has been used entirely in the beneficiary’s maintenance, education or other benefit, or the court directs, only a proportion of the trust fund should be used to maintain the beneficiary. The logic behind this appears to be to preserve the income from the trust fund wherever possible and to rely on other funds to maintain the beneficiary first.

where there is other income available, unless it has been used entirely in the beneficiary’s maintenance, education or other benefit, or the court directs, only a proportion of the trust fund should be used to maintain the beneficiary. The logic behind this appears to be to preserve the income from the trust fund wherever possible and to rely on other funds to maintain the beneficiary first.

If, by the time the beneficiary reaches 18, he does not have a vested interest in the trust property, the trustees must then pay the income from the property to the beneficiary until he either attains a vested interest or dies.

The power to maintain an infant beneficiary under s 31 only gives the trustees a right to maintain the beneficiary. They are not obliged to do so. Under s 31(2), if the trustees do not use the income that the beneficiary is entitled to from the trust property for his maintenance, then that income should generally be accumulated (rolled up). The general position is that the accumulated income should be added to the capital of the trust fund. If, however, the infant beneficiary already has a vested interest during his infancy or upon attaining the age of 18 or marrying under that age becomes absolutely entitled to the trust property, the trustees will not add the accumulated income into the capital of the trust fund but must pay that income directly to the beneficiary.

A power to advance capital to the beneficiaries before they become entitled to it

Again, a trust document may contain an express power to advance capital to the beneficiaries before they become entitled to it. If not, s 32 of the Trustee Act 1925 contains a power for the trustees to advance capital to any beneficiary who is entitled to the capital interest in the trust property. This includes beneficiaries who enjoy either an absolute or contingent interest. The ability under this section is not limited to just infant beneficiaries, as under s 31.

The power is to apply capital money for the ‘advancement or benefit’ of a beneficiary. ‘Advancement’ used to mean using money to establish a beneficiary in an ‘early period of life’.74 Viscount Radcliffe, in Pilkington v IRC,75 identified that such advancements in the nine-teenth century might have been used to purchase an apprenticeship for the beneficiary or an army commission. Lloyd v Cocker76 demonstrated that an advancement could be used to fund a dowry for a woman who was in the process of getting married. The key to all of these advancements was that they established ‘some step in life of permanent significance’.77

‘Benefit’ always appears to have had a wider meaning than advancement. More recently, it has been held to have a very wide meaning with few restrictions imposed upon it, as Pilkington v IRC78 shows.

The case concerned the will of William Pilkington. He provided that his residuary estate should be held on trust in equal shares for his nephews and nieces, living at his death who should attain 21 or marry under that age. Each nephew or niece was only to have a life interest, with the remainder interests being settled on such of their children as they chose with a default trust imposed for the nephews’ or nieces’ own children who attained 21 or married under that age if they failed to make a choice. At best, therefore, the great-nephews and nieces had a contingent reversionary interest in William’s trust fund.

The trustees wished to make an advancement to one of William’s great-nieces, Penelope (who was only five years old), to set up a further trust in her favour. The reason behind the advancement was to save on death duties which would have been due if the trust property had come to her after her father’s death. The advancement was planned to be made by taking a large sum (£7,600) out of the trust under William’s will and placing it on a new trust in favour of Penelope. The Inland Revenue objected to the advancement as they believed it amounted to a completely new trust, something that was not within the scope of s 32 of the Trustee Act 1925.

Viscount Radcliffe thought that the combined meaning of ‘advancement or benefit’ was very wide. He said that the phrase ‘means any use of the money which will improve the material situation of the beneficiary’.79 Section 32 was drafted in very wide terms, so much so that Viscount Radcliffe had not been able to find ‘anything which in terms or by implication restricts the width of the manner or purpose of advancement.’80 It was not relevant that a new trust was being established by the advancement in the case itself, in favour of Penelope and her own children. As long as the beneficiary (Penelope) benefited, it was of no consequence that other people (her own children) might also obtain an incidental benefit from the advancement occurring.

The majority in the Court of Appeal had thought that the beneficiary had to obtain a benefit personal to him or herself if s 32 was to be used successfully. Viscount Radcliffe disagreed with this. He thought that asking trustees only to advance capital if a personal need of the beneficiary justified it was imposing an almost impossible task. As he said, this was a fine distinction to draw:

What distinguishes a personal need from any other need to which the trustees in their discretion think it right to attend in the beneficiary’s interest?81

On the facts, the trustees could have made the advancement under s 32, but the terms of the new settlement infringed the rule as to remoteness of vesting.

Consider the meaning of ‘benefit’ in Pilkington v IRC. Now turn to Chapter 10 and consider the meaning of ‘benefit’ under the Variation of Trusts Act 1958 as interpreted in decisions such as Re Weston’s Settlements. Do you think there is a common thread in these decisions?

The inherent problem with exercising the power of advancement under s 32 is that the capital funds of the trust are depleted. It is no doubt with this in mind that there are three safeguards embodied in s 32:

[a] the trustees can only advance up to one half of the vested or presumptive share that the beneficiary may be entitled to;

[b] if the beneficiary does become entitled to a share in the trust property (for example, because he fulfils the contingency) the advancement that he has already received must be taken into account when calculating the remaining share of the trust property due to him. This is sometimes called ‘hotchpot’; and

[c] no advancement may be made without the prior written consent of any life tenant who may exist. To give valid consent, the life tenant must be 18 years of age or over. This safeguard has been described as the ‘eternal check’82 on the system of advancement.

Suppose Scott sets up an inter vivos trust appointing Thomas as his trustee with £10,000 to Ulrika (currently 45 years old) for life, remainder to Vikas provided he becomes a barrister and attains 30 years of age. Vikas, currently 23, needs an advancement from the trust fund to purchase his barrister’s wig and gown to receive his rights of audience.

Thomas might decide to make use of the power of advancement under s 32. The power of advancement is all about balance. Enabling him to achieve his ambition to become a barrister is arguably both an advancement to him and a benefit. But using the money will deplete the capital available to earn interest to pay to Ulrika. If Thomas is minded to use the power to advance capital to him, he will first need to obtain Ulrika’s written consent. The total sum advanced cannot be more than half of Vikas’ eventual share of the trust fund (£5,000) and it must be taken into account when he finally receives the absolute interest in the trust property.

Duty of Care and Skill Required of a Trustee

When exercising his duties and powers a trustee is bound to exercise them with a particular standard of care and skill.

The first case in which the trustee’s duty of care was discussed was Speight v Gaunt.83

The case concerned the misappropriation of money from a trust fund by a broker, Richard Cooke. Isaac Gaunt was a trustee of the trust created by the will of John Speight. The adult beneficiaries of the trust agreed with the trustee that £15,000 should be invested in local authority bonds. Mr Gaunt mentioned using his own broker to buy the bonds, but the adult beneficiaries preferred him to use their own broker, Mr Cooke. Mr Cooke produced a note to Mr Gaunt, showing that he had committed himself to buy the bonds and that he required the money to complete the transaction. Mr Gaunt duly gave him the money. However, instead of using the money to buy the bonds, Mr Cooke kept it for himself. Mr Cooke was declared bankrupt. The adult beneficiaries brought an action against Mr Gaunt, alleging breach of trust. They wanted him to repay the monies lost to the trust fund.

Jessel MR set out the general standard of skill and care that a trustee should adopt:

a trustee ought to conduct the business of the trust in the same manner that an ordinary prudent man of business would conduct his own, and that beyond that there is no liability or obligation on the trustee.84

He stressed that a trustee should not be subjected to any higher standard of skill and care than anyone else:

In other words, a trustee is not bound because he is a trustee to conduct business in other than the ordinary and usual way in which similar business is conducted by mankind in transactions of their own. It never could be reasonable to make a trustee adopt further and better precautions than an ordinary prudent man of business would adopt, or to conduct the business in any other way.85

The policy reason for this was straightforward: ‘[i]f it were otherwise, no one would be a trustee at all. He is not paid for it.’86