Chapter 2

Classification of Trusts and Powers

Chapter Contents

What Type of Property Can Be Left on Trust?

This chapter builds upon the meaning and history of equity considered in Chapter 1. The focus now shifts to the single biggest item that equity has created in the English and Welsh legal system: the trust. It is the trust which now remains the subject of the remainder of this book (except for Chapter 17), so its importance to equity cannot be overstated.

As You Read

As you read this chapter, look out for:

![]() what a trust is: its concept, how it grew up from its origins in the Middle Ages to today and the different types of property that can be left on trust;

what a trust is: its concept, how it grew up from its origins in the Middle Ages to today and the different types of property that can be left on trust;

![]() the different types of trust within the two over-arching areas of express trusts and implied trusts; and

the different types of trust within the two over-arching areas of express trusts and implied trusts; and

![]() how a trust can be compared to and distinguished from something that may, at first glance, look very similar to it — a power of appointment.

how a trust can be compared to and distinguished from something that may, at first glance, look very similar to it — a power of appointment.

The Trust

As has been seen in Chapter 1, equity’s history is long. It has grown up over centuries into what it is today: a set of legal principles that contributes meaningfully to the English legal system to mitigate the otherwise harsh effects of the common law. The principles — or maxims — of equity are applied in cases today to give results that are designed to be fair and in good conscience.

But equity is not just a series of maxims that are applied by the courts. Those are only the underlying ideas that guide equity. Equity has more structure to it than the maxims suggest.

As has been mentioned in Chapter 1, equity has also given the legal system a set of bespoke remedies when common law damages are not adequate. Those remedies include orders of specific performance, injunctions and the rectification of documents.1

There is, however, one item that equity has given the legal system which far surpasses all of the other items — remedies or maxims — which it has also provided. That item is the trust. It is the greatest asset that equity has bestowed on the legal system. The word ‘asset’ is not used lightly, for as we shall see, it is the concept of a trust that enables the legal system to recognise more subtle shades of ownership than the common law permits.

Definition

Snell’s Equity defines a trust as being formed when:

a person in whom property is vested (called ‘the trustee’) is compelled in equity to hold the property for the benefit of another person (called ‘the beneficiary’), or for some legally enforceable purposes other than his own.2

This concise definition demonstrates that:

![]() it is equity — not the common law — that recognises the trust;

it is equity — not the common law — that recognises the trust;

![]() due to equity being the body that recognises the trust, the basis of the recognition is likely to be conscience and fairness;

due to equity being the body that recognises the trust, the basis of the recognition is likely to be conscience and fairness;

![]() there are normally three parties to the trust, those being the person who originally owns the property, the trustee and the beneficiary; and

there are normally three parties to the trust, those being the person who originally owns the property, the trustee and the beneficiary; and

![]() there does not, in fact, have to be a human beneficiary to benefit from the trust, since the trustee can hold the trust property for some other ‘legally enforceable purposes’.3, 4

there does not, in fact, have to be a human beneficiary to benefit from the trust, since the trustee can hold the trust property for some other ‘legally enforceable purposes’.3, 4

All of these issues are explored later in this chapter.

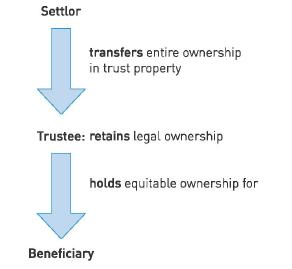

The parties typically involved in the creation of an express trust

In a simple, expressly declared trust, there are three parties involved in the matter. They are:

![]() The settlor. This is the person who creates the trust. He ‘settles’ the property on trust. In order to do this, he transfers the legal ownership of the property to the second person in the arrangement, the trustee.

The settlor. This is the person who creates the trust. He ‘settles’ the property on trust. In order to do this, he transfers the legal ownership of the property to the second person in the arrangement, the trustee.

![]() The trustee. This is the person who administers the trust. The trustee will hold the trust property for the benefit of the third party in the arrangement, the beneficiary. When the trust comes to an end, the trustee must transfer the legal ownership to the beneficiary, but until that time he retains it. Usually it is a good idea to have more than one trustee so that, for example, the burden of trusteeship can be shared. The maximum permitted number of trustees where the trust involves land is four.5

The trustee. This is the person who administers the trust. The trustee will hold the trust property for the benefit of the third party in the arrangement, the beneficiary. When the trust comes to an end, the trustee must transfer the legal ownership to the beneficiary, but until that time he retains it. Usually it is a good idea to have more than one trustee so that, for example, the burden of trusteeship can be shared. The maximum permitted number of trustees where the trust involves land is four.5

![]() The beneficiary. This is the person who benefits from the trust. They will enjoy the equitable interest in the property which is the subject matter of the trust. The beneficiary’s easy task is to reap the rewards of being the person the settlor has chosen to benefit from his gener-osity. As we shall see, however,6 the beneficiary’s harder task is as the enforcer of the trust, making sure the trustee completes his obligations by, if necessary, forcing him to do so. There can be any number of beneficiaries.

The beneficiary. This is the person who benefits from the trust. They will enjoy the equitable interest in the property which is the subject matter of the trust. The beneficiary’s easy task is to reap the rewards of being the person the settlor has chosen to benefit from his gener-osity. As we shall see, however,6 the beneficiary’s harder task is as the enforcer of the trust, making sure the trustee completes his obligations by, if necessary, forcing him to do so. There can be any number of beneficiaries.

The simple trust arrangement can be illustrated by the diagram in Figure 2.1.

Since the trust is a creature recognised by equity, the trustee is obliged to hold the equitable ownership on trust for the beneficiary due to the requirements of fairness and good conscience. By willing to recognise and enforce the trust, equity gives the trustee no other option but to adhere to its terms and will, if necessary, force the trustee to comply with the trust.7

In order to understand those issues, it is essential to have an understanding of how the trust originated.

Where It All Began …

It may have begun like this …

This story of the beginnings of the trust may be real or apocryphal, but it remains a nice tale.

The origins of the trust may be linked to the crusades. The crusades occurred in the time of the Middle Ages and did not just involve English people but also those from other European countries. The crusades were a number of holy wars whose objective was to reclaim the Holy Land around Jerusalem for the benefit of Christians from the Muslims living there.

In all, the crusades led to hundreds of thousands of people, both members of the nobility and those from the lower classes of society, taking up arms to join in the fight for recapturing the Holy Land.

Those crusaders who owned land had a problem. They could — and often would — be away from tending their land for years at a time. What those crusaders needed was someone who could look after their land, manage it and farm it, whilst they were away. Those crusaders did not want to give their land away but instead wanted someone to take temporary custody of it. The land had to be returned to the original landowner on his return from the crusade. The land needed to be given away on a metaphorical piece of elastic, so that its ownership would always bounce back to the original landowner.

The common law, with its blinkered view of matters, could not help the landowner. Even today, if you give something away, the common law sees a change in ownership of the property from you to the recipient. You are no longer the owner at common law. You have given the property away. You have relinquished all claims to it. The common law could not assist the landowner who went away on crusade because the common law was not subtle enough to help with the landowner’s problem. The common law would simply say that the landowner had given his land away to someone else.

Equity, though, with its 3-D glasses, could assist. Equity was capable of looking at the entire situation and seeing that the landowner only wanted to transfer his land to someone else on a time-limited basis. Equity would see that the land was to be, effectively, loaned out and that it was always to be returned to the landowner at the end of the loan period. Equity achieved that outcome through creating and developing the medium of the trust. The landowner would remain the true owner of the land whilst passing the day to day management of the land to someone else whilst he was away on crusade. That manager would then return the land to its rightful owner upon his return. The landowner, it might be said, trusted the manager to look after the land for him during his absence and return it to him on his return. The trust was born.

Note that this crusader’s trust differed from the majority of today’s trusts by only having two parties to it. The manager would take the role of trustee holding the land on trust for the person setting up the trust who was also the beneficiary.

But it probably began like this …

As the victor at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, William the Conqueror had a new prize that he could distribute to his friends and associates who had supported him: England. He began to divide the country up into parcels of land and gave it away to those friends and associates — his chief lords. In turn, those chief lords sub-divided their pieces of land to lords and those lords gave it to other people who did the same until the land found itself being owned by a peasant tenant, at the very end of the chain. Each layer of people made money from it, down to the individual at the bottom of the chain who perhaps farmed the land. This was the concept of feudalism that was established in the early years after the Norman conquest and which grew up over the centuries. The King remained the technical owner of all of the land.

Originally, in return for land being granted from the King to his chief lords and so on, the chief lord would demand services from his lord and each lord from his tenant.

By the beginning of the thirteenth century, actual services being provided by one party to his lord in return for the land were dying out in favour of the tenants paying cash for the privilege of holding their interest in the land. This would enable their immediate successor to purchase any services they actually required. Cash was becoming more and more important in England’s economy.

Related to this concept of each person in the feudal system preferring cash to services was the concept of inheritance. Chattels were not subject to inheritance but land was. The idea of inheritance provided that when a tenant died, the land would pass to his heir. The tenant would not get any choice about this and the concept of the common law recognising a will for a piece of land was anathema.

Death also carried with it another consequence. When the tenant died, privileges became due to the lord or, if it was the chief lord who died, to the King. These privileges were some of the ‘incidents of tenure’. They included:

![]() Customary dues — local customs that were recognised and had to be performed on death. Baker8 gives the example of the ‘custom of heriot’ where the lord could ‘seize the best beast or chattel of a deceased tenant’.

Customary dues — local customs that were recognised and had to be performed on death. Baker8 gives the example of the ‘custom of heriot’ where the lord could ‘seize the best beast or chattel of a deceased tenant’.

![]() The concept of escheat — if the tenant died without leaving an heir, then his land would go to his lord.

The concept of escheat — if the tenant died without leaving an heir, then his land would go to his lord.

Clearly, if a chief lord owned a lot of land, and with the King owning all of the land, the chief lords and the King could be in receipt of a great deal of money upon a tenant’s death.

Probably since the beginning of time, people have tried to circumvent paying any more than they absolutely must to either the King or to whomever they owe money. Whilst tenants could not find a way around death, what they set out to do was to find a way around the inheritance requirements that their land must go to their heir. That is probably where the concept of the trust first arose.

The first use of the trust

The first use of the trust, then, was really to find a way around the rules of inheritance — in other words, to circumvent the requirement that your land had to go to your heir.

It was not possible to make a will of land. The owner of the land had to find some other way to rid himself effectively of his land before he died. If he was able to achieve that objective then, critically, the incidents of tenure applicable on his death would not become due. The tenant would also have some say over who would actually receive his land. This ability to state who should have your land after your death should not be understated and remains a concept of vital importance to most people today.

The key appeared to be that the tenant should take steps to deal with how his land was going to be administered during his life and not wait for the law of inheritance to strike after his death.

The main way that was developed was the concept of the ‘use’.

Glossary: The ‘use’

The ‘use’ has nothing to do with the English verb, to use. It comes from the old French word ‘oeps’. For our purposes, the words ‘use’ and ‘trust’ can be used interchangeably.

A tenant could give the land to his friends on the explicit direction that, after his death, the friends should give the land to whomever the tenant chose. The tenant trusted his friends to honour his instructions hence the concept of the ‘trust’. The concept stopped short of imposing an absolute obligation on the friends that they had to deal with the land as instructed for, if it did this, it would have circumvented the rules on wills too crudely. The arrangement can be represented by Figure 2.3.

This trust reflects the classic tri-partite arrangement described in Snell’s Equity.9

The idea of giving something as serious as a piece of land to someone else on the basis of trust alone was far too flimsy a concept for the common law to recognise. Equity, however, would recognise trusting as a concept since, in the end, it is based on what good conscience should do — good conscience says that if you have been asked to hold a piece of land on behalf of someone else, you should not be allowed to renege on that arrangement. The Court of Chancery, therefore, began to manage trusts and by the 1400s, it consumed much of the court’s time.10

It may have been a bit of both … or something else entirely!

It is not impossible that both the crusades and the wish to avoid inheritance duties both spurred on the development of the trust. The crusades had ended by the closing years of the thirteenth century and we know that, by that stage, the incidents of tenure associated with feudalism were pretty much in full swing. Both crusaders and tenants wanted mechanisms to avoid the common law consequences of what would happen to their land. Both needed to rely on the idea of trusting others to look after their property, which was far too subtle for the common law to appreciate.

Other writers talk about the trust being descended from Franciscan monks who needed property to be held on trust for their benefit but who could not themselves own it due to their vow of poverty.11 In truth, we simply do not know what the facts were which surrounded the creation of the very first trust. Some people like to believe the crusading version of events. History supports the tax evasion version with more facts, but it is by no means impossible that the first trust was used for any version of occurrences.

Split Ownership

The common law was not willing to recognise the concept of a trust. The common law likes definites: someone either owns property or they do not. It had no time for equity’s recognition of ownership of property being based on conscience.

What is left by the two systems running parallel with each other is the concept that it is possible to split ownership of property. As will be seen, this includes all types of property, not just land. At common law, it is possible to have one person owning the property, whilst equity will recognise that the actual benefit of the property is being held for another. Equity does this by saying that the owner has an equitable interest. This is a proprietary interest — an interest in the property which is the subject of the trust — and can be relied upon against the whole world.

Key Learning Point

This is key to understanding a trust. The trust is built upon the basis that ownership of the property is split between the owner of the interest of the property at common law (the trustee) and the owner of the interest in equity (the beneficiary).

Owning the legal interest results in the trustee managing the trust. The equitable interest ensures that the beneficiary can enjoy the fruits of the trustee’s labour.

To try to understand this idea, think of a cream cake. A cream cake consists of cake and fresh cream. Without both cake and fresh cream, the end product is not complete. The trust is like that insofar as it is a mixture of the common law and equity and, without one part, the whole trust is not complete. Yet when looking at a cream cake, it is still possible to identify which part of the object is cake and which part is fresh cream. Depending on your eating preferences, it is possible to separate one from the other. That is true of the trust too: you can identify who owns the property at common law and who owns the property in equity. You can also separate the ownership of the different interests.

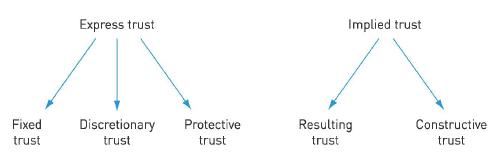

The Different Types of Trust

The expressly created trust is not the only type of trust that is recognised by equity. Figure 2.4 below shows what we might term a ‘family tree’ of trusts.

Each of these must be considered in a little more detail.

Express trusts

The fixed trust

The fixed trust is so called because the interests of the beneficiaries are determined expressly by the settlor when the trust is created. The interests are, therefore, fixed. The trustees must give to each beneficiary what the settlor has expressly provided. So the settlor has deliberately — or expressly — created a trust and fixed the beneficial interests.

If the settlor does not himself define the beneficial shares in a fixed trust, the maxim ‘equity is equality’ applies so that each beneficiary will have an equal equitable share in the trust property.

Scott appoints Thomas as his trustee and transfers £1,000 to him to hold on trust for the benefit of Ulrika. That is an express, fixed trust. It is an express trust because Scott has deliberately created it and it is fixed because Scott has provided that Ulrika is solely entitled to the benefit of the trust property — the money.

This trust is not confined to having just one beneficiary. For example, suppose another time Scott transfers the same amount to Thomas for Thomas to hold on trust for Ulrika and Vikas in equal shares. That means that Ulrika and Vikas will equally enjoy the trust property. It is still an example of an express, fixed trust because Scott has deliberately created it and the equitable interests are still fixed: Ulrika and Vikas are each to have 50 per cent shares in the money.

The example above demonstrates the classic, three-party arrangement in creating a trust.

There is also another way to declare an express trust, just involving two parties. The settlor can say that he himself is a trustee and declare that he holds certain trust property on trust for the beneficiary. Both ways were recognised as equally good alternatives by Turner LJ in Milroy v Lord.12 There is still the three-party arrangement even in this alternative — it is just that one party is wearing two ‘hats’ of both the settlor and trustee.

Declarations of express trusts can be written down but, if the property of the trust is land, they must be evidenced in writing and signed by a person able to declare the trust.13 If the trust property is not land, it may be surprising to know that express trusts can be declared quite informally, as occurred in Paul v Constance.14

Doreen Paul and Dennis Constance began a relationship in 1967. They moved into the same house and lived together, as a couple, until Dennis died in 1974. In 1969, Dennis was injured at work and he received £950 as compensation for his claim. They both decided to open a bank account to put the money in. The account would only be in Dennis‘ name.

From the time the account was opened to Dennis‘ death, more money was paid into it. A small amount of money was withdrawn from the account for them to buy Christmas presents and food and for them to each treat themselves. By the time Dennis died, the account still had the compensation money of £950 remaining in it.

Dennis had been married prior to meeting Doreen. Dennis died without leaving a will so his widow, Bridget, wound up his estate. Bridget claimed that, as the bank account was in Dennis‘ sole name, the entire contents of it belonged solely to him. That money, she argued, became part of Dennis’ estate which she was bound to administer according to the laws of intestacy, as opposed to any of it belonging to Doreen.

Doreen disagreed. She argued that, whilst the legal title of the money had been in Dennis‘ sole name, a trust had been created by him. That meant that the equitable interest in the money was held by both her and Dennis. Doreen argued that Dennis had declared an express trust of the money. The difficulty that she faced was that the trust had been declared only orally and informally.

The Court of Appeal upheld the trial judge’s finding that there was an express declaration of trust by Dennis in favour of both himself and Doreen. In his judgment, Scarman LJ pointed out that:15

one should consider the various things that were said and done by the [claimant] and the deceased during their time together against their own background and in their own circumstances.

Certain facts led to the conclusion that Dennis had orally declared an express trust. These were that they had only opened the account in Dennis‘ sole name due to their embarrassment of having an account in joint names when they were not married, that they had paid in joint earnings, they had both enjoyed the money that was withdrawn and, crucially, that Dennis had said to Doreen on more than one occasion ‘This money is as much yours as mine’ led to the conclusion that an express trust had been declared.

Scarman LJ emphasised the case was near the borderline. It must be clear when an express trust is formed and it was not entirely clear here: was it, for instance, at the time the bank account was opened or at some later point when Dennis had promised Doreen that the money was theirs to share equally?

But the comments of Scarman LJ quoted above illustrate that equity will look at all the circumstances of each situation to decide if a declaration of an express trust has been made. Equity will not blithely permit informal declarations of trust without considering the full factual surrounding circumstances, as shown by Jones v Lock.16

Robert Jones lived in Pembroke. He went on a business trip to Birmingham and when he returned, he was told off by his child’s nanny for failing to bring a present back for his nine-month old son. His reply was to present the child with a cheque for £900, saying to the nanny: ‘Look you here, I give this to baby; it is for himself, and I am going to put it away for him …’. Robert’s wife then warned him that the child was about to tear the cheque up and his response was to put the cheque in his safe.

The issue for the court to decide was whether Robert’s words and actions were enough to declare a trust.

Lord Cranworth LC held that there was no express declaration of trust because he thought that:

it would be of very dangerous example if loose conversations of this sort, in important transactions of this kind, should have the effect of declarations of trust.17

Again, the court looked at the evidence surrounding the actual words used by the alleged settlor. Lord Cranworth LC thought it highly unlikely that Mr Jones would have considered that he had made a once-and-for-all decision to part with such a large amount of money by such a conversation. This crucial fact surrounding the words spoken by Robert showed that a trust had not been declared.

The case also shows that equity will not use a trust as a ‘second-best’ alternative to save a failed gift. As will be seen in Chapter 7, the general rule is that where a gift fails, a trust cannot step in to rescue it.18

Express fixed trusts can be made easily, but the court will look at all of the evidence surrounding the oral declaration to be confident that a trust truly was intended.

The discretionary trust

This is still a type of express trust since it is deliberately created by the settlor. This time, however, the settlor leaves some issues of choice up to the trustees. The settlor may, for example, give the trustees a choice over who should benefit from the trust (within a defined group) and/or to the extent that those whom the trustees choose should benefit. The settlor might prefer to use a discretionary trust if he cannot himself decide who should benefit from a particular group of people.

Scott is feeling generous again and appoints Thomas as his trustee and transfers £1,000 to him to hold on trust for the benefit of those people who live in the same road as Scott. Scott provides that Thomas should use his absolute discretion to choose those people who are to benefit and the amounts by which they are to benefit.

This is again a type of express trust since Scott has deliberately created it. The beneficial interests are not fixed. Instead, Scott has said that Thomas must choose who will benefit from a particular group of people and the extent to which they will benefit. This is a discretionary trust. Problems can arise where the settlor fails to define the group with sufficient precision.19

Trustees of a discretionary trust must choose a recipient (or recipients) from the class of people the settlor has defined. The trustees must then consider how much such a recipient should receive from the trust fund.

The rights of people falling into the group as defined by the settlor under a discretionary trust are interesting. They were considered by Walton J in Vestey v IRC (No. 2).20

Walton J said that, individually, such potential recipients had no ‘relevant right whatsoever’ to enjoy any equitable entitlement from the trust. Instead, as a whole, all of the members of the defined group of the trust could join together and collectively enforce a right to ensure the trustees kept to the terms of the trust. The reason for none of the individuals having rights personally under the trust is, of course, because of the very nature of the trust that has been created. The settlor has created a discretionary trust, to benefit a defined group. Any individual within that group may, or may not, eventually be chosen by the trustees to benefit. Until that individual is chosen, he is not a true beneficiary and has no individual rights. Collectively, however, all of those individuals can join together to enforce the trust against the trustees since — by definition — some of them must be chosen from the group. Once an individual is chosen by the trustee to benefit from the trust, he becomes a true beneficiary and only at that point does he have an equitable interest in the trust property. Until that stage, all he has is a hope of being chosen to benefit.21

The protective trust

This is our third type of express trust. As its name suggests, it is an example of equity acting paternalistically again. It seeks to protect beneficiaries from themselves. It ensures that the beneficiary can enjoy the trust property for their lifetime, but if the beneficiary infringes the trust during their life, it is converted into a discretionary trust.22 This can be shown by an example.

Scott transfers a house to Thomas, his trustee, to hold on protective trust for Ulrika. Scott is concerned that Ulrika has an alcohol dependency which is out of control, but he wants Ulrika to have a home in which to live. Consequently, Scott makes the trust protective by providing that if Ulrika does not seek treatment for alcoholism, the trust will come to an end and will be replaced with a discretionary trust in favour of other people whom Scott defines.

This trust should give Ulrika the incentive to control her alcohol habit by providing that the trust in her favour will end should she continue to consume it to extremes.

Section 33 of the Trustee Act 1925 provides that if the protective trust comes to an end during the original beneficiary’s lifetime, the income from the trust will be held on trust for the original beneficiary, their spouse/civil partner, or their issue as the trustees decide. The trustees have discretion to choose who will benefit from the trust if the original beneficiary infringes its terms. Hopefully, it is that sanction that will ensure the original beneficiary adheres to the terms of the protective trust.

Protective trusts are, at first glance, ideal for avoiding bankruptcy. In an ideal world, a settlor might wish to settle property on trust for himself as a beneficiary, but provide that if he goes bankrupt, a discretionary trust will take its place and the equitable interest in the property will pass to others. Such protective trusts are difficult to create nowadays due to legislation which seeks to protect creditors and disallow trusts to be created which seek to put assets beyond their reach.23

In reality, protective trusts are used rarely, not only due to anti-avoidance insolvency legislation, but also because it is hard to prevent an adult beneficiary from claiming an absolute interest in the trust property. The basic rule is that adult beneficiaries have a right to terminate the trust and enjoy the absolute interest in the property themselves.24 If, in the example above, Ulrika and the other beneficiaries joined together, they would stand a good chance of terminating the trust. We return to this theme in Chapter 10.

Implied trusts

All implied trusts are so called because they are implied by equity into particular situations. They are not expressly created by the settlor. They fill gaps.

Implied trusts are a major topic in their own right and the reader is referred to Chapter 3 for a full discussion.

As Figure 2.4 illustrates, there are two types of implied trust: the resulting trust and the constructive trust.

The resulting trust

This type of trust may occur on either one of two occasions:

(a) when a gift is made by one person to another; or

(b)when the entire equitable interest has not been used up.

(i) when a gift is made by one person to another

In life, we often make gifts to other people. On occasions, though, equity takes a cynical and perhaps protectionist view of such gifts. Equity says that the equitable interest should remain with the giver (the ‘donor’). To achieve this result, equity implies a resulting trust into the situation.

Re Northall (Dec’d)25

This case involved Mrs Northall and her family. In December 2006, she sold her house for nearly £55,000. The house was registered in her name together with Dennis, one of her six sons, as he helped her buy the property. When it was sold, the problem that she had was that she did not have a bank account in which to pay the cheque for the sale proceeds. Another one of her sons, Christopher, opened a joint account in his name and Mrs Northall. The money was paid into it.

Mrs Northall died on 23 January 2007. Between the time the account was opened and her death, Christopher had withdrawn over £28,600 from the account. The day after his mother died, Christopher transferred the remaining money in the account into his own personal bank account.

Action was taken by two of the other siblings against Christopher. His defence was that his mother had told him that she wanted to use the sale proceeds as she desired and that anything left over was to go to him. He claimed that she was giving him the remaining money in the account.

David Richards J held that there was, on the facts, no evidence that Mrs Northall had wanted to make a gift of any of the money to Christopher. Rather, the evidence pointed to the conclusion that she wanted to spend the money herself. She had only put the money into a joint bank account with Christopher for administrative convenience, not because she wanted to give half of her money away to him.

A resulting trust was implied by equity. The presumption to be applied here was that Mrs Northall’s actions of putting the money into her name and her son’s should not be assumed to be giving the money away. Equity could act paternalistically and protect Mrs Northall from losing all control of her money. The common law might recognise the transfer of ownership of the legal title in the money but equity would not. Equity would see the money as still truly belonging to Mrs Northall.

The case is a good example of equity acting according to good conscience. Mrs Northall was a frail woman whom equity would protect. Christopher was ordered by the court to account for the money he had taken from the account, except for some small amounts he was able to prove were withdrawn on his mother’s instructions.

Equity says that even though the legal interest in the gift has been transferred to the recipient, the person giving the gift did not really intend to give their interest away.

(ii) when the entire equitable interest has not been used up

A further equitable principle, but which is perhaps not so settled as to be a maxim, is that equity abhors a vacuum. In other words, equity does not like gaps. As we have mentioned, equity fills gaps with implied trusts and arguably the best example of this occurring is this second species of resulting trust.

If a party successfully shows that they have given property away but that they have not disposed of the entire equitable interest, there is a gap which equity fills by implying a resulting trust.

This was shown on the facts of Vandervell v IRC.26 Mr Vandervell wished to benefit the Royal College of Surgeons and, to do so, he instructed his trustee to transfer his interest in certain shares to the Royal College. An option was retained for the trustee to repurchase the shares from the Royal College at some future point. It was the presence of this option that led the House of Lords to decide that Mr Vandervell had not successfully divested himself of his entire equitable interest in his shares. This meant that he had not successfully transferred any of his equitable interest in the shares to the Royal College. A gap in the equitable ownership resulted: the trustee clearly held the legal title, but the Royal College had never enjoyed the equitable interest. The only logical conclusion was that the trustee held the equitable interest for Mr Vandervell on a resulting trust. The resulting trust could fill in the gap of the equitable ownership.

We return to this in greater depth in Chapter 3.

The constructive trust

The constructive trust is the second type of trust that equity implies.

The constructive trust again reflects the origins of equity in terms of its ideals of fairness and doing what is right according to good conscience. The constructive trust applies when it would be unconscionable to permit a person to claim an equitable interest in property which really belongs to another party.

Profits made by trustees and other parties where there is a relationship of trust and confidence has been a fruitful area for the use of constructive trusts over the years.

The fundamental idea is that if you are in a relationship of trust and confidence with another person, you should not be allowed to make any profit from that relationship in a secretive manner.27 The relationship between trustee and beneficiary is one of trust and confidence.

The relationship between a solicitor and a client is also one where trust and confidence is implied. So if, in my former life when I was a solicitor in private practice, I decided to make money for myself by gambling my clients‘ money that they gave me to purchase their house or office, I would have had to account to my clients for any proceeds (or more likely, losses) that I made. Equity would not have allowed me to keep any secret profit that I made as a result. It would have imposed a constructive trust on me and I would have been a constructive trustee of the money with my clients having the equitable interest in it. With my clients as the equitable owners of the money, they would have been able to compel me to hand the money over to them.

Equity would have imposed a constructive trust on me because it would have been unconscionable for me to retain the proceeds of the winnings as those winnings really belonged to my clients. I would not have made the winnings unless I had used my clients‘ money to do so.

But, as will be seen in Chapter 3 , bad faith on the trustee’s part is not needed for a constructive trust to be imposed upon him. It is the fact that the trustee has made a gain (and such gain can be made entirely honestly) that means he is made a constructive trustee of the gain.

What Type of Property Can Be Left on Trust?

The fundamental principle is that any type of property can be left on trust. ‘Property’ can be split into two different broad categories:

[a] real property which is sometimes shortened to ‘realty’.This is essentially freehold land. The ability to leave realty by trust was a device which has existed since the Middle Ages; and

[b] personal property, which is sometimes shortened to ‘personalty’. This encompasses every other type of property. For instance, it therefore includes chattels and goods. These are called ‘choses in possession’ — they are things that a person possesses which are tangible, such as a car or a vase.

Personalty also includes leasehold land and choses in action. Choses in action are rights that are not tangible such as bank accounts or shares in a company. They are called ‘choses in action’ because they are rights which depend on you taking action should you wish to enforce them.

Think about your own bank account. If you walk into the local branch of your bank, you cannot ask to see your own personal bank account because it does not exist in a physical sense. It would be impractical to expect a bank to keep everyone’s account physically in their own local branch — the banks would need far larger buildings to do so. Instead, the amount in your account is a debt that the bank owes to you. You have a right to demand the balance from your bank, by legal action if necessary.

A similar concept is applied to company shares. If you own shares in a company such as British Gas plc, you cannot physically see those shares. You may have a share certificate, but that is just a formal piece of paper stating how many shares you own. You do not physically possess the actual shares in the company. Rather, you have a right against the company for a sum of money to the amount of shares that you own. Your right is a chose in action as it depends on you taking action to obtain anything from it.

Trusts can be created of both realty and personalty and, of course, a mixture of the two.

The Express Trust

When can express trusts be created?

There are two occasions on which a settlor can deliberately create a trust:

[a] During his lifetime. A trust created by the settlor to take effect whilst he is alive is also known by its Latin name as being created inter vivos; and

[b] Upon his death. A trust created by the settlor to take effect on his death is one that the settlor creates in his will or, if he fails to make a will, by the laws of intestacy.

Trusts created during the settlor’s lifetime can, if they consist just of personalty, be made entirely orally. Best practice must be for the settlor to write down the terms of the trust so that each party can be sure that a trust has been created and the nature of its terms.

Trusts of land expressly created by the settlor during their lifetime must be evidenced in writing and signed by some person who is able to declare the trust.28 Any trust expressly created by the settlor’s will, whether consisting of realty, personalty or both, must comply with the formal requirements set out in section 9 of the Wills Act 1837. Such trusts created by will are subject to far more formal requirements than those created during the settlor’s lifetime, simply because they are contained in a will and there is no opportunity to question the settlor about such trusts when they take effect, since they take effect on the settlor’s death.

Section 9 of the Wills Act 1837 provides that the will containing the trust must be:

[a] in writing;

[b] signed by the settlor or some other person at his direction and in his presence;

[c] witnessed by at least two witnesses present at the same time; and

[d] each witness must then either sign the will or acknowledge his signature in the settlor’s presence.

It’s not all that straightforward: the different types of equitable interest

Trusts exist because equity recognises the concept that the legal and equitable interests in property can be split and owned by different people at the same time. There can, of course, be more than one beneficiary enjoying the ownership of the equitable interest. If there are two or more beneficiaries, their interests should be set out by the settlor. The settlor has a number of different options from which he can choose and these are set out below.

First, the beneficiary’s interest can be either in possession or in remainder. If the former, the beneficiary will be able to enjoy the trust property straightaway; if the latter, he must wait for a current beneficiary’s interest to end before he can enjoy it.

Second, the beneficial interest can be either vested or contingent. This is all about whether the beneficiary must fulfil any condition before he enjoys the trust property. If he has no condition to fulfil, his interest is vested; if he must meet a condition, he enjoys a contingent interest. As soon as any condition is met, the beneficiary’s interest changes from vested to contingent.

Lastly, the beneficiary can enjoy an absolute or limited interest. An absolute interest means the beneficiary can enjoy the capital of the trust property and therefore it is his to do with as he wishes. A limited interest is more restrictive and means the beneficiary usually enjoys the interest for his lifetime only. He cannot spend the capital of the trust property and it is invested on his behalf for him to enjoy the products of that investment instead.

The settlor must choose one option from each of the three discussed when creating the trust. The following example shows an illustration of a settlor creating a trust having chosen from the options discussed.

Scott settles £1,000 on trust. He appoints Thomas as his trustee and instructs Thomas to hold the money on trust for:

[a] Ulrika for her lifetime, provided she qualifies as a solicitor but if not or thereafter, as the case may be; or

[b] Vikas absolutely.

This example shows that Ulrika’s equitable interest has the following characteristics:

[a] it is in possession, because she is the first beneficiary who can benefit from the trust property and she has no other beneficiary whose interest is before hers;

[b] it is a contingent interest because to be entitled to any of the trust property, she must qualify as a solicitor. If she does not qualify as a solicitor, then she is not entitled to benefit; and

[c] it is a limited interest because she can only enjoy the trust property for her lifetime. This means she can only have the income from the £1,000 and cannot generally have access to the capital sum itself.

Vikas’ interest has the following characteristics:

[a] it is in remainder, because the interest has a prior one before it (Ulrika’s). Only when Ulrika has died or fails to become a solicitor is Vikas entitled to the trust property;

[b] it is a vested interest, because there is no condition that Vikas must fulfil before he becomes entitled to the trust property; and

[c] it is an absolute interest because it is not limited in any way. This means that, when he becomes entitled to the interest, he will have full access to the trust property and may do with it as he wishes.

What are the uses of express trusts?

Trusts are deliberately created nowadays for a variety of purposes. Significant practical uses of trusts include:

![]() houses;

houses;

![]() pensions;

pensions;

![]() charities; and

charities; and

![]() taxation avoidance.

taxation avoidance.

Houses

Where more than one person owns their home, they are obliged to hold it under a trust.29 Section 36(2) of the Law of Property Act 1925 provides that two or more people who own the house must own the legal estate as joint tenants. The law, this time in the form of a statute, is typically inflexible.

Equity is more flexible. Equity enables the co-owners of the property to have a choice. The co-owners can hold the equitable interest in the property either as joint tenants or as tenants in common. As has been seen,30 holding the property as tenants in common is the more flexible method of ownership of the two, since the parties are then free to leave their share to whomsoever they choose in their will. Equity permits the maximum possible choice for co-owners to decide the proportions in which they each own the property. Their choice should be recorded on the purchase deed.31

If co-owners do not record their main choice as to whether to hold the property in equity as joint tenants or tenants in common, then equity will, prima facie, follow the law in holding that the parties hold the equitable interest as joint tenants. Equity will, however, depart from this presumption in a number of situations. The most common are:

[a] if the parties pay unequal contributions to the purchase of the property. If two people make unequal contributions to the purchase of the home, then the presumption must be that they intended their equitable interests to reflect those unequal contributions;

[b] if the parties hold the property not as a family home but as a business. Equity presumes that business parties prefer a more commercial relationship and would not want their shares to pass automatically to their business partner upon their death; or

[c] if there are any words which go against the idea that the parties intended to own the property as joint tenants in the purchase deed. These are known as ‘words of severance’.

Pensions

Often people save for their retirements by paying into a pension scheme. There are a number of different schemes available, from pension schemes which are entirely dependent on the individual’s contributions to those entirely provided by a person’s employer as a perk of the job. Lots of people who are employed enjoy a pension which is perhaps a mixture of the two — so the individual will make contributions to it from their monthly salary but the employer will also make payments to it.

Pensions are a modern use of the trust in practice. In straightforward terms, the money which is paid into each scheme is transferred to trustees. Those pension trustees then hold the money on trust for the individual who benefits from the pension. When an individual retires and reaches the age prescribed by the scheme, they can start to claim the benefits from the trust. In reality, nowadays, pension administration is big business.

Large companies, such as Standard Life plc, act as pension trustees and administer pension funds. They do this by endeavouring to grow pension funds by investing them in a wide range of opportunities which will hopefully secure growth of funds for the benefici-aries. That is why often nowadays you see business parks with words akin to ‘a Standard Life investment’ at the foot of the entrance sign. Have a look next time you go past a business park to see evidence of trusts in action.

Pensions are types of express trusts, since they are deliberately created by the individual or their employer. Schemes provided by employers are known as occupational pension schemes. These schemes are also types of discretionary trusts. The amount the individual will benefit from in retirement depends on a number of variables, such as how many other beneficiaries there are in the pension scheme and how successfully the money that has been paid in over the years has been invested. People join and leave pension schemes all the time as, for example, they change employers. It is consequently not practicable to make use of the express fixed trust as far as pensions are concerned. There has to be flexibility built into the scheme for when new people join it. Remember that a fixed express trust dictates that trustees must hold property on trust for clear, fixed beneficiaries. Whilst a discretionary trust must still define its beneficiaries clearly, it is the mechanism used for typical occupational pension schemes because it enables beneficiaries to be defined by reference to a group.32 As more people join the group, they can be included in the beneficiaries who will be entitled to benefit from the scheme because they form part of a group.

There are restrictions on who can be a trustee for an employer-funded scheme. The Pensions Act 2004 seeks to protect such schemes by providing that at least one-third of the trustees of the scheme are nominated by the beneficiaries.33 Such nominated trustees must come from either the current members of the scheme who are still making payments into the scheme or those who have retired.34 Once appointed, a member-nominated trustee can only be removed if all of the other trustees agree.35

Charities

Charities have been in existence since at least the time of Elizabeth I.36 Some of the main charities in England and Wales are very well known — charities such as the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) and Barnardo’s are examples of national charities. The law of charities is an area of law in its own right,37 but for now, we can see that they are examples of the use of the trust, albeit a use of the trust with slight twists to it.

Property is held by charitable trustees. There is no maximum number of charitable trus-tees who can hold land,38 unlike non-charitable trustees.39 Charities are also an exception to the typical arrangements of trusts where there is a settlor, a trustee and a beneficiary. A settlor will still have originally created the charitable trust and trustees still hold the property on trust, but unusually in English law, there does not have to be any human beneficiary for the trust to be valid. Instead, it is permissible (and, indeed, entirely usual) to leave property on trust for a charitable purpose. These purposes are now set out in the Charities Act 2011,40 but the list in that Act is not exhaustive since all charitable purposes decided as charitable before the Act came into force will continue to be charitable.41

Taxation avoidance

The probable first use of the trust was as a means of avoiding taxation. That use remains today as one of the main uses of a trust. Taxation is a highly complex subject with volumes of books devoted to it so some very introductory principles only can be given here.

Tax is generally payable by the person in whose hands money is made. For example, income tax is payable on income that you receive. Income may be generated through different methods — for instance, as a result of being employed, as a result of dividend payments received on shares that you own or perhaps you receive rent from property that you let out to tenants. The income that you receive is taxed in bands, with a certain amount of money earned being free of tax and the remainder being charged at different rates.

In the tax year 2012–2013, the amount of income those aged under 65 can earn before tax is charged is £8,105. After that, income tax is payable at the basic rate of 20 per cent for money earned between £0 and £34,370 and at the higher rate of 40 per cent for money earned between £34,371 and £150,000. Those earning above £150,001 must pay income tax at the additional rate of 50 per cent.

As you can see from the above example, the more income you have, the more income tax you pay.

A trust may help you to minimise those tax charges, as illustrated in the following example.

Suppose Scott owns several large houses that he rents out. He also has a significant shareholding in a private company that is doing very well. His income through employ-ment is sufficient to mean that he is already a higher rate taxpayer. He wishes to minimise his tax liabilities if possible.

What he could do is set up a trust and settle the houses and shares on trustees for, say, the benefit of his children. His children are under 18 so are not taxpayers. That means that any income from the houses and shares are treated as theirs since income tax is payable by the recipients of the money.

What that means is that the taxation liabilities are minimised. The disadvantage for him is that he cannot claim interests in the houses and shares once he has placed them on trust. If he continues to enjoy interests in them, then he will be taxed accordingly.42

A word of warning about using a trust to minimise tax. It is lawful to seek to minimise tax liabilities by proactively seeking to set your affairs in order so that your charges to tax are reduced. You cannot seek to retrospectively re-order your affairs once the tax is due, however. That is called tax evasion and is something upon which HM Revenue & Customs is not too keen!

A related concept to the trust is the power of appointment.

Powers of Appointment

The central feature of a trust is that it is an obligation. It obliges a trustee to hold property on trust for a beneficiary. Naturally, depending on the terms of the trust, the trustee may have some room for manoeuvre when managing the trust or even deciding who will benefit. The Trustee Act 2000 significantly enlarged trustees‘ decision-making powers of investment43 and a trustee can go so far as to be able to choose the beneficiaries in a discretionary trust.44 In the end, though, the trustee has no choice that he must hold property on trust and someone or something, in the case of a trust for a purpose,45 must benefit from the trust.

A power of appointment is fundamentally different from a trust. A power of appointment gives the trustee the ability to choose whether someone else will benefit from it. The trustee is not obliged to ensure that someone will benefit.

Glossary

The terminology changes a little for powers of appointment as opposed to trusts:

The Potential Recipient under a power of appointment will only become an object if chosen to benefit by the donee.

Trust or power of appointment?

In drafting terms, there is often a thin line between creating a trust, or creating a power of appointment. Tomlin J in Re Combe46 said that, in cases of difficulty in deciding whether a provision was a trust or a power of appointment, the matter had to be resolved in accordance with the ‘ordinary principles of construction’.47 That would involve giving the language used in the drafting its ordinary and natural meaning.

This is easier said than done, though, as is shown by comparing two cases which featured provisions which, at first glance, look very similar in terms of their actual wording.

In Re Sayer,48 the governing director of Sayers (Confectioners) Ltd wished to provide ‘grants allowances annuities or payments’ for a group of people which included his employees, ex-employees or their dependants. A committee was ‘empowered at its discretion’ to administer payments to anyone who fell within that group. Upjohn J held that the ability of the committee to distribute the money took the form of a power. By the wording used, the committee had the right, but not the obligation, to benefit individuals.

Similar wording of a clause can have a different result, as illustrated by Re Saxone Shoe Co Ltd’s Trust Deed.49 The case again concerned a fund which was to provide benefits for employees, ex-employees or their dependants. Clause 6 of the deed provided that the fund and income from it ‘shall in the discretion of the directors be applicable for’ such people. The question again arose as to whether this wording made the directors subject to a power or whether they were under an obligation to distribute the fund in the form of a trust.

This time, the High Court’s decision was that a trust had been created. Again, the decision turned upon the actual words used, as had been suggested in Re Combe. Cross J believed50 that the words ‘shall be applicable’, together with other provisions of the deed setting up the fund, pointed towards an obligation being imposed upon the directors of the company.

The difficulty is that there is not usually a nice, neat distinction between trusts and powers of appointment. The impression given so far is that there is: that there are two distinct types of document that a person might create: one a trust and the other a power of appointment.

Instead, what usually happens is that there is a mixture of the two concepts in the one document. This, in fact, occurred in both Re Sayer and Re Saxone Shoe Co Ltd’s Trust Deed. In both cases, a settlor established an overarching trust which then went on to contain the provisions discussed above. As we have seen, the High Court reached differing results as to whether these internal provisions within the overarching trusts took the form of either a power of appointment or a trust. Which of these two results is reached will depend on the wording used, coupled with the context in which the relevant provision sits in the document.

The distinction over whether there is a power or a trust matters because a power by itself may be exercised fairly freely by the donee. The donee has a lot of discretion and may even choose not to exercise the power at all. These powers of appointment — where the donee has a great discretion as to whether anyone from a class should benefit at all — may be called ‘mere’ or ‘bare’ powers.

Key Learning Point

To understand the difference between a power of appointment and a trust, you need to grasp that:

• a power of appointment may be exercised by the donee; but

• a trust must be executed by the trustee.

The rights of the eventual recipient under a mere power or a trust differ too. Under a mere power, the potential object has no rights over the property itself, since they may or may not be chosen by the donee to benefit from the property. In Vestey v IRC (No. 2),51 Walton J held that a potential object has three limited rights under a power:

(i) the right to be considered by the person exercising the power when he comes to exercise it; (ii) the right to prevent certain kinds of conduct on the part of the person so exercising the power — e.g., by distributing part of the assets to not within the class — and (iii) the right to retain any sums properly paid to him by the trustees in exercise of their discretionary powers. But beyond that he has no relevant ‘right’ of any description ….52

Megarry V-C summarised the issue succinctly in Re Hay’s Settlement Trusts53 when he said:

The essence of that difference [between a trust and a power of appointment], I think, is that beneficiaries under a trust have rights of enforcement which mere objects of a power lack.54

The concept to which Megarry V-C was referring is also known as the beneficiary principle. This is considered in Chapter 6 but, for now, understand that the beneficiary also acts as an enforcer of the trust, ensuring that the trustee honours the terms of the trust. An object of a power has no such comparable role.

What types of powers of appointment can be given to trustees?

A power given to a trustee can either take the form of a mere power or, alternatively, may impose on the trustee some form of obligation. The mere power gives the trustee a wide right of discretion, as occurred in Re Sayer. There the trustees had the ability to make grants to certain people but in the end, it was entirely at their discretion over whether they did so. In contrast, a settlor may give a power to a trustee under which a trustee must exercise his discretion. This type of power was the type given in Re Saxone Shoe Co Ltd’s Trust Deed. The trustees still had some discretion — as to who benefited from the trust fund — but fundamentally they had to choose people who would benefit. Such powers are known as ‘trust powers’ or, in more modern terminology, discretionary trusts.

The court can control the exercise of a trust power by, if necessary, forcing the trustees to exercise it or exercising it in place of the trustees if they fail to do so. All of the beneficiaries can collectively force the trustees to pay the fund to them, provided they are 18 years old or over and have mental capacity. A mere power cannot be controlled by the court in such a manner since the operation of it is at the entire discretion of the donee.55 Lord Upjohn set out what he described as the ‘basic difference’ between a mere power and a trust power in Re Gulbenkian’s Settlement as follows:

in the first case [that of a mere power] trustees owe no duty to exercise it and the relevant fund or income falls to be dealt with in accordance with the trusts in default of its exercise, whereas in the second case [that of a trust power] the trustees must exercise the power and in default the court will.56

Yet, if a mere power is given to a trustee, the trustee is under more duties than if a power of appointment was simply given to a non-trustee. Trustees are duty bound to act in accordance with their fiduciary duties of trusteeship.57 Megarry V-C set out some of those obligations in relation to mere powers in Re Hay’s Settlement Trusts.58 He said the trustees had to:

[a] consider actively whether to exercise the power from time to time;

[b] exercise the power in a responsible manner by considering the ‘range of objects’ within the power (in other words, by considering the size of the group that the settlor has defined); and

[c] consider whether it was appropriate for particular individuals to benefit from the power.

The latter two obligations on trustees arise by virtue of their being trustees and the nature of the office of trusteeship being fiduciary. By contrast, a non-trustee donee of a mere power has a much easier time of it. Such a donee has complete freedom over whether or not even to exercise the power in favour of a potential beneficiary, let alone be obliged to undertake the activities that Megarry V-C suggests.

Types of powers

Powers which are either of the mere or trust type can be one of three categories:

![]() general;

general;

![]() special; or

special; or

![]() intermediate/hybrid.

intermediate/hybrid.

General powers of appointment

A general power of appointment is the widest one possible. It enables the donee to choose anyone in the world to benefit from the power. As anyone at all can benefit from the power, that means that the donee could conceivably simply choose himself alone! Clearly, that would be akin to the donor just giving the donee the property for his own benefit. Presumably if the donor had intended that course of action all along, he would not have set up a power at all but would simply have given away the property straightforwardly to the donee.

Special powers of appointment

This power of appointment is at the other end of the spectrum to the general power. The special power of appointment is where the donor restricts the donee’s choice over who can benefit from the power. The choice is restricted to a particular group.

Intermediate/hybrid power of appointment

This is a combination of the other two types of power. It was described by Harman J in Re Gestetner’s Settlement59 as ‘something betwixt and between’ the other two. Here the donor gives the donee the ability to choose from anyone at all but specifically excludes people if they fall into a particular group.

The facts of Re Hay’s Settlement Trusts60 are an example of the intermediate power of appointment. In the case, a settlement was created by Lady Hay for the benefit of such people as the trustees were to decide — in other words, the trustees could choose anyone in the world to benefit. Specifically excluded in the trust deed, however, were Lady Hay herself, her husband and any present or past trustee. These exclusions turned the otherwise general power of appointment into an intermediate one.

Any of these types of powers can be created as mere powers or, if given to trustees, can take the form of trust powers.

The operation of a power

The difficulty that arises is how a donee actually exercises a power. This issue can arise because it is often not clear who the donor actually wants to benefit from the power. The whole purpose of a power is to give the donee some discretion over which members of a group — or class — will benefit. The donor will hopefully have assisted to some extent by creating a general, special or intermediate power, but it is still often unclear how the donee is to decide whether a potential beneficiary actually falls within that class or not.

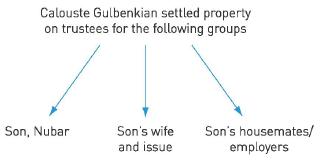

Lord Upjohn laid down guidelines in Re Gulbenkian’s Settlement.61 In the case itself, a philanthropist called Calouste Gulbenkian created two trusts, one in 1929 and the other in 1938. In effect, the wording of both trusts was identical. Both trusts sought to leave property on trust for the maintenance and support of a particular class of people: Mr Gulbenkian’s son, Nubar, his son’s wife and issue (if any) and anyone that Nubar either resided with, or employed, but those who were to benefit were to be at the trustees‘ discretion. This was a mere power as the trustees were under no duty to exercise it.

The facts are summarised in the diagram at Figure 2.5.

In order that they should even be able to consider exercising the power, the trustees had to know in whose favour the power should be exercised. The question for the House of Lords, therefore, was whether the mere power was valid in the sense of whether the class that was defined was sufficiently certain so that the power could be operated by the trustees knowing which type of people were entitled to benefit. Lord Upjohn said that the court had to:

[a] try to ascertain the settlor’s intention. To do this, the court would start by giving the words used their natural meaning; but

[b] if the words used were not clear, then the court would try to make sense of the settlor’s intentions in order to give a reasonable meaning to the language used. The court would use its ‘innate common sense’62 to do so.

The test then to be applied was the following one:

a mere … power of appointment among a class is valid if you can with certainty say whether any given individual is or is not a member of the class; you do not have to be able to ascertain every member of the class.63

Key Learning Point

The test enunciated by Lord Upjohn in Re Gulbenkian’s Settlement is known as the ‘individual ascertainability’ or ‘given postulant’ test, since it focuses on the concept of asking whether an individual can fall within the group defined by the settlor.

In the case of a power to benefit those from a class, therefore, the donees‘ job was to focus on the individual and ask if it is possible to say that, hypothetically, a person could be a member of the class as defined by the donor. If the answer to that is a definitive ’yes‘ or ’no‘, the given postulant test is fulfilled and there is sufficient certainty in the description of the class as defined by the settlor. The power is valid. If, on the other hand, it is impossible to say that any one person is definitely in the class or not because the wording of the class by the settlor is too vague, then the defined class will not pass the given postulant test. In this case, the class will not be sufficiently certain and the power will be void. The given postulant test demands a concrete answer as to whether any person can or cannot definitely fall within the class and if there is any doubt as to whether one person could or could not, the class fails and the power is void.

The focus is on the individual. The donee does not have to draw up a complete list of all those people who might be entitled to benefit from the trust.64 Donees do not have to ‘worry their heads to survey the world from China to Peru, when there are perfectly good objects of the class in England’65 in order to draw up a definitive and complete list of beneficiaries of the power. There is no point in them doing this, since each potential beneficiary is almost certainly not eventually going to benefit from the power in any event. All the donee has to do is to consider that the class of people, as defined by the settlor, is reasonably certain in terms of saying that a given person definitely can or cannot fall within the class.

Some classes will usually be regarded as too uncertain in their definition to be capable of being enforced. Lord Upjohn gave the example of a donor leaving property to be divided equally amongst a class being defined as ‘my old friends’.66 Such a class is uncertain because it is normally impossible to say who is a friend of somebody else’s. For instance, you might say that someone is definitely your friend and that another person definitely is not. You probably know a number of people whom you regard neutrally — they are neither your friends nor ‘non-friends’. They may be simply people you have met and whom you get along with quite well. As there are such people who it is impossible to say whether they are your friends or not, a class of ‘my old friends’ must be, by definition, uncertain.

Yet a class of ‘friends’ was held to be sufficiently certain in Re Barlow’s Will Trust.67

Helen Barlow died in 1975, leaving a valuable collection of paintings. In clause 5(a) of her will, she provided that her ‘friends’ could purchase these paintings at a price that was lower than the present valuation. The issue was whether this clause was valid as it was argued that ‘friends’ had previously been held to be an uncertain concept.

Browne-Wilkinson J held that, in this situation, ‘friends’ was conceptually uncertain but that the dispositions did not fail because of this. The reason was because the case did not revolve around one gift to a group of people that either stood or failed in its entirety. Instead, the option to purchase the paintings at a discounted price represented a series of gifts to those people who were friends of the testatrix. It was not relevant to try to ascertain whether one class of people that could be defined as ‘friends’ of Ms Barlow was certain, since she had never intended to leave the paintings simply to one class of people. Instead, she wanted her friends to benefit on an individual basis, not on the basis that they formed one class for the purpose of taking one gift.

Whilst not wishing to lay down any hard rules, Browne-Wilkinson J gave some guidance68 as to when a person could be seen to be a ‘friend’ of another. He described the following as the ‘minimum requirements’:

[a] a long-standing relationship was needed;

[b] the relationship had to be social, as opposed to professional; and

[c] the two parties must have met ‘frequently’ when circumstances permitted.

This case is, however, deciding a different issue from that in Re Gulbenkian’s Settlement, as Browne-Wilkinson J was at pains to justify. It was not necessary to identify all the members of the class in this case since the gift was never intended to go to all members of the class. Instead, the case decided that a gift to ‘friends’ could be valid, but only where a series of gifts was left to a series of friends.

Has the concept of ‘friend’ changed since 1979? In an age of amassing ‘friends’ through social networking sites would someone who you have never met, but who you contact frequently online, fall within the category of friends in a Re Barlow-type situation?

Would these online friends meet Browne-Wilkinson J’s requirement that there should be a long-standing relationship? Would regular correspondence through social networking sites on a regular basis amount to meeting frequently?

Browne-Wilkinson J also suggested that the relationship needs to be a social rather than professional one. However, nowadays much more socialising goes on with work colleagues and even bosses — would people who you have got to know through work but who are now friends be excluded? The obiter comments of Browne-Wilkinson J about “minimum requirements” are unlikely to be seen as being set in stone. If a court were faced with a Re Barlow-style situation in the future it may well take a much more modern approach to the concept of friend.

The operation of trust powers is considered in Chapter 5, under its more modern name of ‘Discretionary Trusts’.

Points to Review

We have seen:

![]() how the trust grew up from the Middle Ages;

how the trust grew up from the Middle Ages;

![]() the fact that there are different types of trust, of both express and implied varieties. Express trusts are deliberately created by the settlor. Implied trusts are not so deliberately created but exist to fill gaps in the equitable ownership of property;

the fact that there are different types of trust, of both express and implied varieties. Express trusts are deliberately created by the settlor. Implied trusts are not so deliberately created but exist to fill gaps in the equitable ownership of property;

![]() how express trusts are created and used today; and

how express trusts are created and used today; and

![]() how powers of appointment, whilst outwardly a similar concept to a trust, are actually different from the trust.

how powers of appointment, whilst outwardly a similar concept to a trust, are actually different from the trust.

Making connections

Before you move on, you will benefit from having a good understanding of this chapter. It is essential that you understand the basics of trusts and powers, since these form the foundations upon which the main building blocks of trusts law are constructed. So, please, take a minute now to ask yourself whether you really grasp the material on the different types of trust that can be created, the tri-partite arrangement typically involved in creating a trust and the subtleties of powers of appointment.

If you do not grasp that material in particular, make sure you go back through this chapter and re-read it. The different types of implied trust are examined in greater depth in the next chapter. You need to know the people who are involved in the typical trust arrangement as this forms the basis of the material in Chapter 4 to 7. Understanding powers of appointment underpins the operation of the discretionary trust, which is examined in Chapter 5.

Useful Things to Read

Useful Things to Read

A number of additional things to read are set out below, which you may wish to read to gain additional insights into the areas considered in this chapter.

Secondary sources

J H Baker An Introduction to English Legal History (4th edn, Butterworths Lexis-Nexis, 2002) chs 13 and 14. This contains a good account of the nature of both feudal tenure and the concept of the original ‘use’, the predecessor to the trust.

Roy T Bartlett, ‘When is a “trust” not a trust? The National Health Service Trust’ (1996) Conv May-June 186–192. This article considers a contemporary use of the trust by the NHS and asks whether it can truly be considered a trust under equity’s jurisdiction or whether it is an example of a corporate body.

David Hayton, ‘Pension trusts and traditional trusts: drastically different species of trusts’ (2005) Conv May/Jun 229–246. This explores pension trusts in more detail than this chapter and compares the differing obligations on trustees of such trusts with the obligations on trustees of traditional family trusts. For an update on the principle of Re Hastings-Bass, please see Chapter 12.

A Hudson, Equity & Trusts (7th edn, Routledge-Cavendish, 2012) ch 2.

Maurizio Lupoi, ‘Trust and confidence’ (2009) LQR 125 (Apr) 253–287. This article looks at the history of trusts in England and argues that European learning played an important role in the development of the trust.

J A McGhee, Snel’s Equity (32nd edn, Sweet & Maxwell, 2010) chs 9, 19 and 20. This considers the issues raised here from a practitioner’s viewpoint.

M Macnair, ‘Equity and conscience’ (2007) OJLS 27(4) 659–681. This article considers the role of conscience in the development of equity from the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries.