Human Resource Management and Productivity

Nicholas Bloom*, *Stanford, Centre for Economic Performance and NBER

John Van Reenen**, **London School of Economics, Centre for Economic Performance, NBER and CEPR

Abstract

In this chapter we examine the relationship between Human Resource Management (HRM) and productivity. HRM includes incentive pay (individual and group) as well as many non-pay aspects of the employment relationship such as matching (hiring and firing) and work organization (e.g. teams, autonomy). We place HRM more generally within the literature on management practices and productivity. We start with some facts on levels and trends of both HRM and productivity and the main economic theories of HRM. We look at some of the determinants of HRM—risk, competition, ownership and regulation. The largest section analyzes the impact of HRM on productivity emphasizing issues of methodology, data and results (from micro-econometric studies). We conclude briefly with suggestions of avenues for future frontier work.

Keywords

Human resource management; Productivity; Personnel Economics

E-mail addresses: [email protected] (Nicholas Bloom), [email protected] (John Van Reenen).

JEL classification: L2; M2; O32; O33

1 Introduction

Traditionally, labor economics focused on the labor market rather than looking inside the “black box” of firms. Industrial sociologists and psychologists made the running in Human Resource Management (HRM). This has changed dramatically in last two decades. Human Resource Management (HRM) is now a major field in labor economics. The hallmark of this work is to use standard economic tools applied to the special circumstances of managing employees within companies. HRM economics has a major effect on the world through teaching in business schools and universities, and ultimately what gets practiced in many organizations.

HRM covers a wide range of activities. The main area we will focus on will be incentives and work organization. Incentives include remuneration systems (e.g. individuals or group incentive/contingent pay) and also the system of appraisal, promotion and career advancement. By work organization we mean the distribution of decision rights (autonomy/decentralization) between managers and workers, job design (e.g. flexibility of working, job rotation), team-working (e.g. who works with whom) and information provision.

Space limitations mean we do not cover matching (see Oyer and Schaefer, 2010) or skill development/training. Second, we will only devote a small amount of space to employee representation such as labor unions. Third, we should also mention that we focus on empirical work rather than theory (for recent theory surveys see Gibbons and Roberts, forthcoming, and in particular Lazear and Oyer, forthcoming) and micro-econometric work rather than macro or qualitative studies. Fourth, we focus on HRM over employees rather than CEOs, which is the subject of a vast literature (see Murphy, 1999, or Edmans et al., 2008, for surveys).

Where we depart from several of the existing surveys is to put HRM more broadly in the context of the economics of management. To do this we also look in detail at the literature on productivity dispersion.

The structure of the chapter is as follows. In Section 2 we detail some facts about HRM and productivity both in the cross sectional and time series dimension. In Section 3 we look at the impact of HRM on productivity with an emphasis on methodologies and mechanisms. In Section 4 we discuss some theoretical perspectives, contrasting the usual “Design” approach to our concept of HRM as one example of “management as a technology”. In Section 5 we discuss some of the factors determining HRM, focusing on risk, competition, ownership, trade and regulation. Section 6 concludes.

2 Some facts on hrm and productivity

2.1 HRM practices

In the 1970s the general assumption was that incentive pay would continue to decline in importance. This opinion was based on the fact that traditional unskilled jobs with piece-rate incentives were declining, and white collar jobs with stable salaries and promotion based incentives were increasing. Surprisingly, however, it appears that over the last three decades a greater proportion of jobs have become rewarded with contingent pay, and this is in fact particularly true for salaried workers.

There are two broad methods of assessing the importance of incentive pay: Direct and Indirect methods. Direct methods use data on the incidence of HRM, often drawn from specialist surveys. Indirect methods use various forms of statistical inference, ideally from matched worker-firm data, to assess the extent to which pay is contingent on performance. We deal mainly with the direct evidence and then discuss more briefly the indirect evidence.

2.1.1 HRM measured using direct methods

Incentive Pay

Individual incentive pay information is available from a variety of sources. Using the Panel Study of Income Dynamic (PSID) Lemieux et al. (2009) estimate that about 14% of US prime age men in 1998 received performance pay (see Fig. 2.1). They define a worker as receiving performance pay if any part of compensation includes bonus, commission or piece rate1 (data on stock options and shares is not included). They find a much higher incidence of performance pay jobs (37% on average between 1976–1998) defined as ajob where a worker ever received some kind of performance pay2.

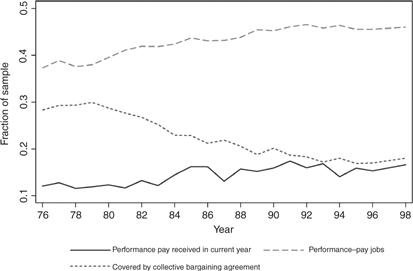

Figura 2.1 Incidence of performance pay, US men in PSID, 1976–1998. Notes: Male heads of household earning between $1 and $100 per hour. Self employed and public sector excluded. 30,424 observations on 3181 workers. Performance pay in current year = 1 if any part of compensation includes bonus, commission or piece rate. Stock options and shares are not included. A performance pay job is one where the worker ever receives some performance pay over the life of the job-match. (Source: Lemieux et al. (2009))

Other papers deliver similar estimates of around 40% to 50% of US employees being covered by some form of performance pay. For example, using the US General Social Survey Kruse et al. (2009) estimate that 47% of American workers were covered by some group incentive scheme in 2006. Of this 38% of employees were covered by profit sharing, 27% by gain-sharing, 18% by stock ownership (9% by stock options) and 4.6% by all three types. Lawler and Mohrman (2003) surveyed Fortune 1000 corporations between 1987 and 2002 asking detailed questions on their HRM3. Using midpoints of their results (which are in bands) Lemieux et al. (2009) calculate that 44% of workers were covered by incentive pay in 2002.

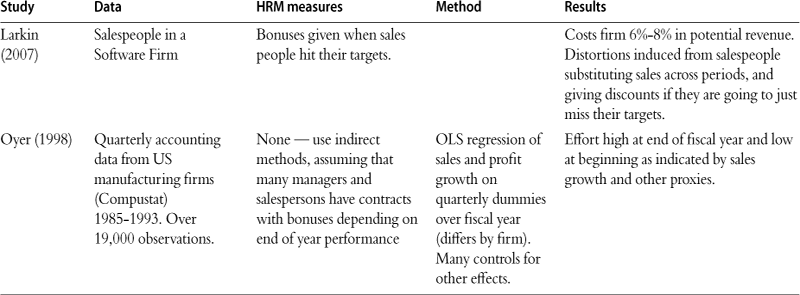

It is also interesting to look at the trends in incentive pay over time. In US data, Lemieux et al. (2009) find that for the wider definition of performance pay (if the worker was eligible for any performance related pay) the incidence rises from 38% in the 1970s to 45% in the 1990s (see Fig. 2.1). Interestingly, this rise in performance pay was mostly driven by increases in performance pay for salaried workers, for whom this rose from 45% in the 1970s to 60% in the 1990s. In contrast hourly paid workers have both lower levels and growth rates in performance pay. Lawler and Mohrman (2003) show similar rises in performance pay, increasing from 21% (1987) to 27% (1990) to 35% (1996) to 45% (2002). Lazear and Shaw (2008) also show some trends reproduced in Table 2.1, showing again that performance pay increased over time in the US.

Table 2.1

Increases in incentive pay in large publicly listed US firms.

Source: Lawler et al. (1995, 2001), Lawler and Mohrman (2003).

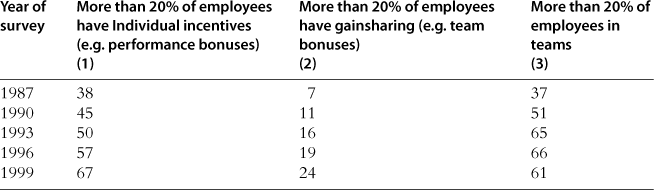

In the UK the British Workplace Employment Relations Surveys (WERS) contains a cross section of all establishments with 25 or more employees in the UK (over 2000 observations in each year). There are consistent questions in 1984, 1990 and 2004 on whether the firm used any form of performance/contingent pay for workers both individually and collectively (e.g. team bonuses, Profit-related pay or Employee Share Ownership Schemes). Figure 2.2 shows that 41% of UK establishments had contingent pay in 1984, and this rose to 55% twenty years later. Two other points are noteworthy. First, this time series change is driven by the private sector: not only was the incidence of incentive pay very low in the public sector 10% or less, it actually fell over time (Lemieux et al., 2009 exclude the public sector in their US analysis). Second, the growth of incentive pay in the UK is primarily in the 1980s with no growth in the 1990s, similar to the US results shown in Fig. 2.1.

Figura 2.2 Trends in performance Pay 1984–2004, UK. Notes: This data is derived from the UK Workplace Employment Relations Surveys (WERS) in 1984, 1990 and 2004. This is a representative sample of all UK establishments with over 25 employees. Although there were other WERS in 1980 and 1998 the questions are not consistent. The consistent question relates to the incidence of any form of contingent pay for workers (Individual, Collective—such as team bonuses, Profit-related payor Employee Share Ownership Schemes). The incidence of contingent pay grewfrom 41% to 56% by 1990, but fell to 55% in 2004. The data relates to whether there was any incidence of this type of pay—we do not know how many workers were covered or what proportion of their remuneration was contingent. (Source: Pendleton et al. (2009))

So in summary, the evidence is that overall performance pay related covers about 40% to 50% of US workers by the 2000s, has been increasing over the last three decades, particularly over the 1970s and 1980s and particularly in the private sector salaried jobs. A number of reasons have been suggested for the increase in performance related pay which we will examine in detail in Section 5 below.

Other HRM practices

Turning to more general forms of HRM than pay, like self-managed teams, performance feedback, job rotation, regular meetings, and training it becomes rather harder to summarize the existing information. In the cross section there are a number of surveys, with different sampling bases, response rates and questions making them hard to compare. Perhaps the most representative example for the US is Black and Lynch (2001, 2004) who collected information from a survey backed by the US Department of Labor (used also by Capelli and Neumark, 2001). In 1996, for example, about 17% of US establishments had self-managed teams, 49% in formal meetings and 25% in job rotation. Lawler and Mohrman (2003)’s data of larger firms unsurprisingly shows a greater incidence of “innovative” HRM practices. In their data for 1996, 78% of firms had self-managed teams and this covered at least 20% of the workforce for just under a third of all corporations.

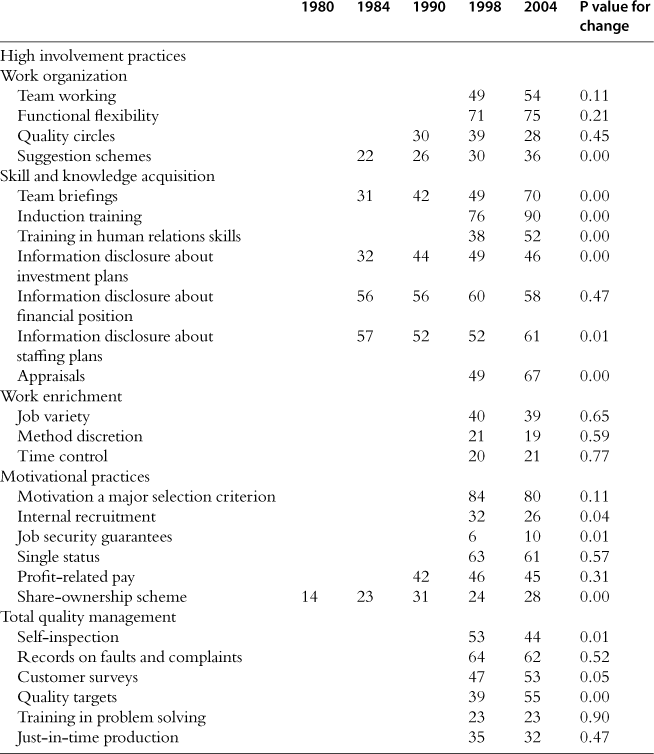

Bryson and Wood (2009) present an analysis of “high involvement” HRM using the UK WERS data (see Table 2.2). About half of all UK establishments had “team-working” in 1998. More interestingly, the WERS data allows an analysis of changes over time. The incidence of teamwork (as indicated by “team briefings”) has grown from 31% in 1984 to 70% in 2004 and “suggestion schemes” has grown from 22% in 1984 to 36% 20 years later. Most other forms of innovative HRM look stable, however, with the exception of incentive pay that has already been discussed.

Table 2.2

Trends in general HRM using British WERS survey.

The following variables relate to practices as they pertain to the core non-managerial occupation at the workplace; team-working (equals 1 if 80%+ core employees in teams); functional flexibility; appraisals (equals 1 if all core employees appraised); work enrichment. Single status is if core workers are treated the same as managers in terms of benefits such as pensions.

Source: Bryson and Wood (2009) based on UK WIRS/WERS data.

Wider international comparisons

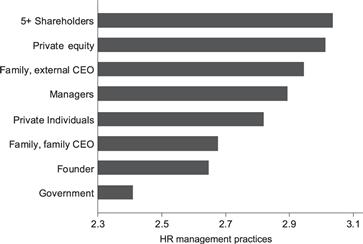

To compare a wider basket of countries beyond the UK and US the best source of information is probably the Bloom and Van Reenen (2007) surveys on general management practices. These have some specific questions on HRM or “people management”, which have been collected from 17 countries. Since we will refer to this work at several points we describe the methodology in a little detail as it is somewhat different than the standard HRM surveys described above. The essential method was to start with a grid of “best practices” in HR and non-HR management and then score firms along each of the eighteen dimensions of this grid following an in-depth telephone interview with the plant manager. These eighteen dimensions covered three broad areas: monitoring, target setting and people management (see Bloom and Van Reenen, 2007, Appendix Table A1 for details). The people management section covers a range of HR practices including whether companies are promoting and rewarding employees based on worker ability and effort; whether firms have systems to hire and retain their most productive employees; and whether they deal with underperformers through retraining and effective sanctions. For example, we examine whether employees that perform well, work hard and display high ability are promoted faster than others.

To obtain accurate responses from firms the survey targeted production plant managers using a “double-blind” technique. One part of this double-blind technique is that managers are not told they are being scored or shown the scoring grid. They are only told they are being “interviewed about management practices for a piece of work”. To run this blind scoring we used “open” questions since these do not tend to lead respondents to a particular answer. For example, the first people management question starts by asking respondents “tell me how does your promotion system work” rather than a closed question such as “do you promote on ability (yes/no)”. Interviewers also probed for examples to support assertions, for example asking “tell me about your most recent promotion round”. The other side of the double-blind technique is interviewers are not told in advance anything about the firm’s performance to avoid prejudice. They are only provided with the company name, telephone number and industry. Since the survey covers medium-sized firms (defined as those employing between 100 and 5000 workers) these would not be usually known ex ante by the interviewers.

These management practices were strongly correlated with firm’s performance data from their company accounts (total factor productivity, profitability, growth rates, and Tobin’s Q and survival rates). These correlations are not causal but do suggest that HR practices that reward effort and performance are associated with better firm performance, implying that these “good” management practice measures do contain some useful information and are not just arbitrary noise. Other research shows that these practices are also associated with better patient outcomes in hospitals (Bloom et al., 2010c) and improved work-life balance indicators (Bloom et al., 2009c).

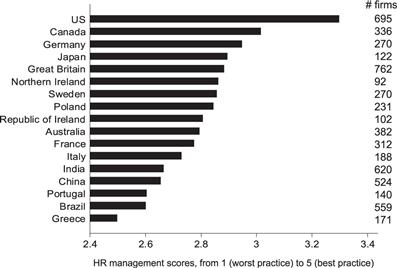

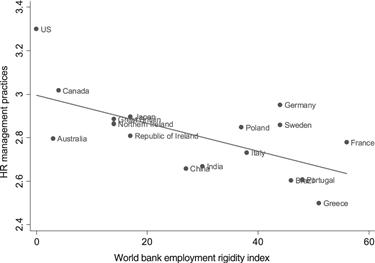

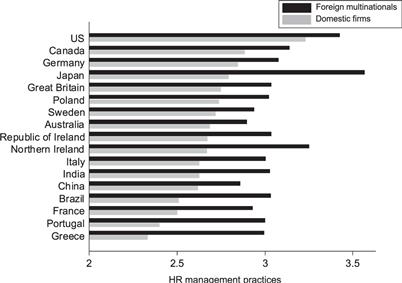

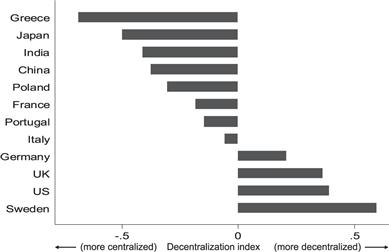

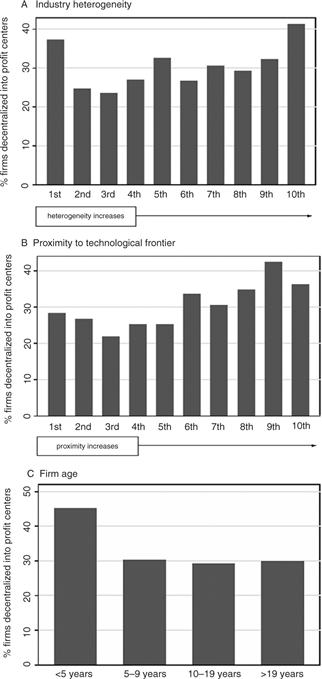

Figure 2.3 shows the distribution of these people management practices across countries. The US clearly has the highest average scores for people management. Bloom et al. (2009b) show that this appears to be due to a combination of the US being absolutely good at managing firms across all 18 questions on average, and also having a particular advantage in people (HR) management. Other countries with light labor regulation like Canada, Great Britain and Northern Ireland also display relatively strong HR management practices. Interestingly Germany and Japan also fare well, in large part reflecting the fact that these countries have generally well managed manufacturing firms.

Figura 2.3 HR management practices across countries. Notes: Averages taken across a random sample of the population of medium sized (100 to 5000 employees) manufacturing firms within each country. 5850 observations in total. Firms per country in the right column. Scores firms on seven practices around pay, promotions, retention and hiring, where high scores denote strongerassociation with employee performance. (Source: Authors’ calculations from Bloom et al. (2009b) data)

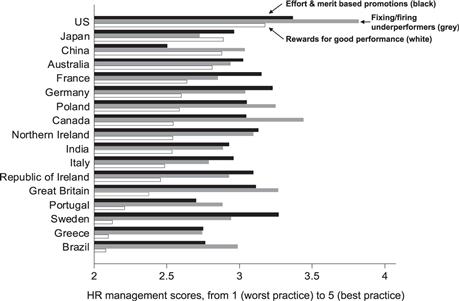

Figure 2.4 breaks out the people management score into three of the key areas in the overall people management score, which are promotions, fixing/firing underperformers and rewards. What is clear is that US firms have the globally highest scored practices across all three dimensions, but are particularly strong on “fixing/firing” practices. That is, in the US employees who underperform are most likely to be rapidly “fixed” (dealt with through re-training or rotated to another part of the firm where they can succeed), or if this fails fired. In contrast in countries like Greece and Brazil underperforming employees are typically left in post for several months or even years before any action is taken to address them. In Section 4.1 we discuss reasons for these patterns. Broadly speaking, the high levels of competition and low incidence of family firms are the main contributing factors to the leading position of the US in overall management. On top of this, high levels of education and weaker labor regulations give American firms a particular advantage in the HR aspect of management.

Figura 2.4 Promotions, fixing/firing, and rewards practices by country. Note: Averages taken across a random sample of medium (100 to 5000 employees) manufacturing firms within each country. 5850 observations in total. (Source: Bloom et al. (2009b))

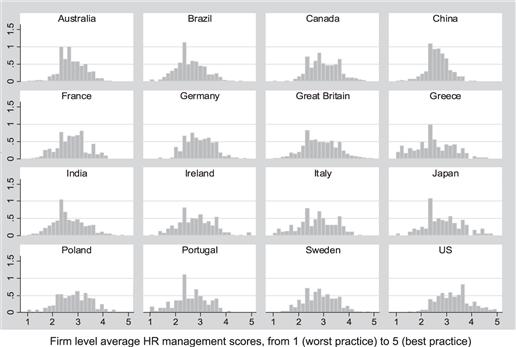

Figure 2.5 displays the firm level distributions within each country for these management practices, showing there is a wide dispersion of practices within every country. The US average score is the highest because it has almost no firms with weak HR management practices, while Brazil and Greece has a large tail of firms with poor HR management practices. This wide variation within each country is what most of the prior micro literature has focused on, with Fig. 2.5 showing this variation is common across every country we have investigated.

Figura 2.5 Firm level distribution of HR management by country. Notes: Bars are the histogram of the density at the firm level on a country by country basis. Randomly sampled from all medium sized (100 to 5000 employee) manufacturing firms in each country. (Source: Bloom et al. (2009b))

2.1.2 Measuring incentive pay through indirect methods

The indirect method has been common in labor economics mainly due to data constraints. Essentially this method examines the correlation of workers’ remuneration with firm-specific characteristics that should be important if pay is contingent on performance such as profitability, market value, etc. For example, if there are profit-related pay schemes, increases in firm profits should cause increases in worker pay. If pay was set solely on the external labor market, it should be unrelated to idiosyncratic changes in the firm’s financial position. An advantage of this approach over the direct approach is that many of the incentive schemes may not be explicitly written down as contracts. A disadvantage is that the correlations between firm performance and pay we observe may be unrelated to incentive schemes for econometric reasons—e.g. a positive demand shock may simultaneously raise a firm’s profitability and mean it hires workers of an unobservably higher skill level. Further, to the extent we do credibly identify a causal effect of firm performance on worker pay we cannot discern easily whether this is due to explicit contracts, implicit contracts, union bargaining4 or some other model.

Having said this, there is substantial evidence that firm performance does matter a lot for worker remuneration. This is clearest in the many studies of matched worker firm data, which generally shows an important role for firm characteristics in determining worker wages (e.g. Abowd et al., 1999). Simple OLS regressions of changes of wages on changes of firm’s profitability tend to find a positive effect (e.g. Blanchflower et al., 1996), but these are likely to be downward biased as shocks to wages will tend to reduce profitability. Using trade-based (Abowd and Lemieux, 1993) or technology-based (Van Reenen, 1996) instrumental variables tends to significantly increase the effect of firm performance on wages as we would expect. Matched worker-firm data is now commonly available in a large number of countries (see the collection of papers in Lazear and Shaw, 2008, for example). In the US, for example, Abowd et al. (2008) use the LEHD (Longitudinal Employer- Household Dynamics Program) covering about 80% of all employees. They show that about one half of all individual wage variance is associated with individual characteristics and about a half due to firm effects.

Although the focus of the literature has mainly been on explaining the distribution of wages at a point in time Dunne et al. (2004) show that between firm effects are important in understanding the growing inequality of wages over time in the US. Faggio et al. (2007) also find this for the UK and furthermore, offer evidence that the association of firm performance with wages has grown stronger over time. This is consistent with the more direct evidence discussed above that performance pay (explicit or implicit) may be more prevalent in recent years.

2.2 Productivity dispersion

Research on firm heterogeneity has a long history in social science. Systematic empirical analysis first focused on the firm size distribution measured by employment, sales or assets. Most famously, Gibrat (1931), characterized the size distribution as approximately log normal and sought to explain this with reference to simple statistical models of growth (i.e. Gibrat’s Law that firm growth is independent of size). In the 1970s as data became available by firm and line of business, attention focused on profitability as an indicator of performance (e.g. Kwoka and Ravenscraft, 1986). Accounting profitability can differ substantially from economic profitability, however, and may rise due to market power rather than efficiency.

In recent decades the development of larger databases has enabled researchers to look more directly at productivity. The growing availability of plant-level data from the Census Bureau in the US and other nations, combined with rapid increases in computer power has facilitated this development. Bartelsman et al. (2008) offer many examples of the cross country micro-datasets now being used for productivity analysis.

One of the robust facts emerging from these analyses is the very high degree of heterogeneity between business units (see Bartelsman and Doms, 2000). For example, Syverson (2004a) analyzes labor productivity (output per worker) in US manufacturing establishments in the 1997 Economic Census and shows that on average, a plant at the 90th percentile of the labor productivity distribution is over four times as productive as a plant at the 10th percentile in the same four digit sector. Similarly, Criscuolo et al. (2003) show that in the UK in 2000 there is a fivefold difference in productivity between these deciles.

What could explain these differences in productivity, and how can they persist in a competitive industry? One explanation is that if we accounted properly for the different inputs in the production function there would be little residual productivity differences5. It is certainly true that moving from labor productivity to total factor productivity (TFP) reduces the scale of the difference. For example, in Syverson (2004a) the 90–10 productivity difference falls from a factor of 4 to a factor of 1.9, but it does not disappear.

These differences show up clearly even for quite homogeneous goods. An early example is Salter (1960) who studied the British pig iron industry between 1911 and 1926. He showed that the best practice factory produced nearly twice as many tons per hour as the average factory. More recently, Syverson (2004b) shows TFP (and size) is very dispersed in the US ready mix concrete industry. Interestingly, the mean level of productivity was higher in more competitive markets (as indicated by a measure of spatial demand density) and this seemed to be mainly due to a lower mass in the left tail in the more competitive sector consistent with the thin tail of bad management in Fig. 2.5 for US firms compared to those of other countries. Studies of large changes in product market competition such as trade liberalization (e.g. Pavcnik, 2002), foreign entry into domestic markets (Schmitz, 2005) or deregulation (e.g. Olley and Pakes, 1996) suggest that the subsequent increase in aggregate productivity has a substantial reallocation element6.

A major problem in measuring productivity is the fact that researchers rarely observe plant level prices so an industry price deflator is usually used. Consequently, measured TFP typically includes an element of the firm-specific price-cost margin (e.g. Klette and Griliches, 1996). Foster et al. (2009) study 11 seven-digit homogeneous goods (including block ice, white pan bread, cardboard boxes and carbon black) where they have access to plant specific output (and input) prices. They find that conventionally measured revenue based TFP (“TFPR”) numbers actually understate the degree of true productivity dispersion (“TFPQ”), especially for newer firms as the more productive firms typically have lower prices and are relatively larger7.

Higher TFP is positively related to firm size, growth and survival probabilities. Bartelsman and Dhrymes, (1998, Table A.7) show that over a five year period around one third of plants stay in their productivity quintile. This suggests that productivity differences are not purely transitory, but partially persist.

Analysis of changes in aggregate productivity over time has shown that this productivity dispersion is also important in explaining economic growth. For example, Baily et al. (1992) find that half of the change in US industry-level productivity is due to the reallocation of output from lower productivity plants to those with higher productivity. This reallocation effect is partly due to the shift in market share between incumbents and partly due to the effects of exit and entry. Bartelsman et al. (2008) show that the speed of reallocation is much stronger in some countries (like the US) than others. There is also significant sectoral variation. For example, Foster et al. (2006), show that reallocation between stores accounts for almost all aggregate productivity growth in the US retail sector.

In summary, there is a substantial body of evidence of persistent firm-level heterogeneity in firm productivity (and other dimensions of performance) in narrow industries in many countries and time periods. Differential observable inputs, heterogeneous prices and idiosyncratic stochastic shocks are not able to adequately account for the remarkable dispersion of productivity. So what could account for this? One long suggested factor is management practices, with authors going back at least to Walker (1887) suggesting that management practices play an essential role in explaining differences in performance across firms8.

3 The effects of hrm on productivity

Do variations in variations in HRM practices play a role in driving differences in productivity? We find that the answer is “probably, yes”, although the empirical basis for this is surprisingly weak given the importance of the topic. In fact, as Syverson (forthcoming) notes in discussing management as a driver of productivity “no potential driving factor of productivity has seen a higher ratio of speculation to empirical study”.

We should also state in advance that in this section we focus on productivity as the key outcome. Many studies look at other outcomes such as worker turnover, absenteeism, worker perceptions, etc. These are useful, but if they have no effect on productivity then in our view they are second order—generally studies use them because they have no direct evidence on productivity (e.g. Blasi et al., 2009:4). We do not focus on measures of worker wellbeing such as job satisfaction or wages. Lazear and Shaw (2008) suggest that some of the dramatic increase in wage inequality in the US, UK and other country since the late 1970s is due to HRM practices. Lemieux et al. (2009) and Guadalupe and Cunat (forthcoming) also take this position, although the current state of the evidence is still limited. These are interesting outcomes in their own right, and may also feed through into productivity, but we are space constrained and refer the reader to the wider literature where relevant.

An important issue is the correct way to econometrically estimate production functions and TFP. Ackerberg et al. (2007) have surveyed such methods in a recent Handbook chapter, and this is a lively (but still unsettled) area of research. Many of the issues on econometric identification of the parameters of conventional factors of production (such as labor or capital) are the same as those that will be discussed in Section 3.2 below. There is also a growing literature on examining the impact of worker characteristics (or “human resources” such as skills, gender, race, seniority and age) on productivity through direct estimation in production functions rather than the traditional approach of looking at these indirectly through including them in wage equations. Interested readers are referred to recent examples of this approach in Moretti (2004), Hellerstein et al. (1999) and Dearden et al. (2006).

3.1 Why should we expect to see an impact of HRM on productivity?

Before discussing issues of identification and the results from these studies, it is worth asking some basic questions: (a) why is this an interesting empirical question? and (b) why would we expect to see any positive average effect of HRM practices on productivity? Note that the answer to this question is not specific to human resources, but any endogenously chosen organizational feature of the firm.

One response is that we should not expect to see any effects. The design perspective on HRM (discussed more fully in Section 4 below) assumes that all firms are continuously optimizing their HRM practices. This may vary between firms because of different environments—for example, variations in technologies across industries—but each firm is still optimizing. Externally manipulating the firm to “force” it to do something sub-optimal (e.g. adopt incentive pay schemes) can only harm the firm’s performance. By contrast, using actual changes in the firm’s choices of HRM (such as Lazear’s (2000) Safelite Glass example discussed below) will show that firms improve productivity as they will be optimizing so we expect any change to produce a positive outcome on average.

An important rejoinder to this is that firms maximize discounted profits, not productivity. It may increase productivity to introduce a given HRM practice, but this may still reduce profits, which is why firms have chosen not to adopt. One example is (Freeman and Kleiner, 2005), who found that the abolition of piece rates reduced productivity but increased profits as quality rose in the absence of piece rates. This is analogous to any factor input such as capital—increasing capital per hour will increase output per hour, but the firm already takes this into account in its maximization program. Thus, just as we are interested in estimating the parameters of a conventional production function for capital and labor, we may be interested in the parameters associated with an HRM augmented production function even if all management practices are chosen optimally.

A second reason for studying the effect of HRM on productivity is that if we do see any effect, we are interested in the mechanisms through which this effect is working. For example, we expect the introduction of incentive pay to affect the type of workers who want to join and leave the firm. How important are these sorting and selections effect relatively to the pure incentive effect? Moreover, even if we expect a positive effect, we may not be so interested in the average effect but rather how this varies with observable characteristics of sub-groups of workers, or of the firm or of its environment. Theory suggests that changing HRM will have heterogeneous effects in this way, so this places some more testable restrictions on the data.

Finally, we describe below in Section 4, theories that regard some management practices partially as a technology. In this case the investigation of the productivity effects of HRM is analogous to examining the effects of the diffusion of any “hard” technology such as computers or hybrid corn. With a new technology we generally expect to see slow and staggered diffusion across firms. Some of this is due to firms optimizing given heterogeneous costs and benefits in a full information world. But slow diffusion may also be due to the differential arrival rate of information about the new technology. More subtly, the optimal HRM type may have changed over time. For example, performance pay may now be optimal in many sectors where previously it was unprofitable due to rapid falls in the cost of Electronic Resource Planning systems (such as SAP) that measure worker output (but not effort) more accurately and rapidly. If the “management as technology” perspective is correct, we would expect to see positive productivity effects from the adoption of these new HRM practices.

3.2 HRM and productivity: the identification problem

The typical study in the HRM and productivity literature in Personnel Economics examines the change in HR policy (typically an incentive pay reform) in a single firm, and a key concern is the effect on worker productivity. As Shaw (2009) points out, this set-up looks extremely similar to the literature on policy evaluation and its concern with correctly identifying treatment effects. Of course, in standard policy evaluation the arena is usually larger than a single firm—a country or state; and the policy maker the government rather than the CEO. Nevertheless, all the many issues germane to identifying treatment effects are present and we discuss these links in this subsection. For a longer discussion on different treatment effects (Local Average Treatment Effects, Marginal Treatment Effects, etc.) and estimation strategies (IV, control function, regression discontinuity design, matching, etc.) see DiNardo and Lee (2011) orBlundell

and Costa-Diaz (2009).

To be precise, let dit represent the treatment status of individual i at time t. Potential outcomes (productivity) are ![]() and

and ![]() under the treated and non-treated scenarios. These are specified as

under the treated and non-treated scenarios. These are specified as ![]() for the treated and

for the treated and ![]() for the non-treated, where ai is the effect of the policy on individual i, c the common intercept and un the unobservable error. We assume that the policy effects are heterogeneous over individuals. This allows us to write the potential outcome equation as:

for the non-treated, where ai is the effect of the policy on individual i, c the common intercept and un the unobservable error. We assume that the policy effects are heterogeneous over individuals. This allows us to write the potential outcome equation as:

yit = c + αidit + uit.

There are a variety of treatment effects that we may be interested in. The traditional one in the homogenous treatment case is the average treatment effect (ATE), defined as the average outcome if an individual was assigned at random to the treatment group, E(αi). More commonly, we can only identify the Average Treatment on the Treated effect (ATT), which is the average effect for the individuals who went through the program at some point, E(αi|di = 1), where di indicates an individual who is assigned to treatment, even if they are not currently being treated.

Consider the model where each individual i is observed before and after the policy change at times to < k and t1 > k respectively. The popular Difference in Differences (DD) estimator makes the assumption that the error term, uit, takes a variance components form: uit = ηi + τt + εit, where ηi is correlated with di, τt is a common time effect, but εit is orthogonal to the other right hand side variables.

![]() (1)

(1)

Sequential differencing eliminates the fixed effect and the time effect so that

![]()

where ![]() is the average outcome in group d at time t. Under the difference in difference assumptions we recover the average effect of treatment on the treated. This is equivalent to adding in time dummies and individual fixed effects in estimating Eq. (1).

is the average outcome in group d at time t. Under the difference in difference assumptions we recover the average effect of treatment on the treated. This is equivalent to adding in time dummies and individual fixed effects in estimating Eq. (1).

Most of the HR studies have longitudinal data so they are able to do the first difference ![]() . However, many studies do not have a control group in the firm who are not treated, thus there is no second difference. This is a drawback because the second difference controls for unobservable time shocks that are common to the two groups but unobserved to the econometrician. In other words, a major concern is that the supposed effect of the HRM policy is actually just some other event simultaneously dated with the introduction of the program.

. However, many studies do not have a control group in the firm who are not treated, thus there is no second difference. This is a drawback because the second difference controls for unobservable time shocks that are common to the two groups but unobserved to the econometrician. In other words, a major concern is that the supposed effect of the HRM policy is actually just some other event simultaneously dated with the introduction of the program.

In fact, many of the studies discussed below do have some more variance than just before and after for a single organization. First, the object of study may be a few firms in a narrowly defined industry (which is the usual strategy in Industrial Organization). Second, there may be variation in the introduction of the policy across different sub-units within the firm (e.g. different plants, different geographical regions9, different production lines, different teams, etc.). Exploiting this form of variation, however, highlights the classical assignment problem—even if the macro time shock is common between the two groups, the decision to adopt the policy for plant A and not to adopt it for plant B is unlikely to be exogenous.

To see this, consider an assignment rule which is dit = 1 if ![]() and dit = 0 otherwise, where

and dit = 0 otherwise, where ![]() is a latent index defined by the linear rule:

is a latent index defined by the linear rule:

![]() (2)

(2)

In other words, plants that introduce the HRM policy may also be those that the CEO thinks are most likely to benefit from it. If this could all be captured by observables then we would be able to control for this bias. But we are unlikely in most datasets to have such a rich set of controls.

The credibility of the identification of treatment effects from cross-plant variation will hinge on the assignment rule of Eq. (2), which is of course a selection equation. Lazear (2000), for example, argues that the rollout of the policy across regions within Safelite Glass was essentially unrelated to differential potential benefits being determined by geography. Bandiera et al. (2007) examine whether similar productivity increases occurred at the same time in the season in a previous year when the policy experiment was not in place (a placebo test).

Having information on productivity prior to the policy is clearly helpful in considering selection. Lazear (2000) and Bandiera et al. (2007) can show that workers who ex ante had lower productivity were less likely to be selected into employment ex post. Since the selection mechanism in both papers means the more able workers are more likely to be employed, the ATT effect will be an upper bound of the effect on the compliers.

What is the advantage of single firm studies? Single firm studies are now the dominant form of methodology in Personnel Economics, but given the problem of the absence of an obvious control group, one might wonder whether this is such a good idea. Usually it is thought that focusing on a single firm enables researchers to control for many aspects that would be impossible to deal with in a larger cross-firm study. But what does this exactly mean?

Consider the possibility that we have multiple firms j = 1,..., J as well as multiple workers, i = 1,..., I, and the difference in difference assumptions hold. Further, let us assume that there is some exogenous within firm variation that enables us to identify the ATT from a single firm estimation strategy.

![]() (3)

(3)

If each firm j is “different” in the sense it has different time shocks (τjt), then estimating Eq. (3) by including a common time shock τt, as is typically done in the cross firm literature (e.g. Black and Lynch, 2004), will generally produce inconsistent estimates of the ATT effect. However, one could include firm dummies interacted with time dummies in Eq. (3) and recover the ATT in each firm j if the treatment randomly varied by worker within each firm. This would clearly be more informative than just recovering the ATT for one firm alone.

As second possible advantage of single firm strategies is that we may simply not have comparable policies across firms, in the sense that the policy changes dijt are not measured in the same units. To some extent this is true, but there are ways in which different policies can be made comparable. In the work on tax policies for example, we need to calculate what effect a tax reform has on the incentives facing individuals. If policies are incomparable then the generalizability of such studies is severely limited.

A third possible advantage of single firm studies is sheer institutional detail. Knowing a single firm well may make it possible to collect more detailed information and rule out many of the alternative explanations that might explain the results.

All three possible advantages of confining attention to a single firm strike us as differences in degree rather than in kind. The future of the field may be to move away from purely single firm studies to consider larger numbers of firms who are subject to HRM policy interventions where we have better ways of measuring the relevant management policy in a comparable way. One way to do this is to explicitly run experiments on firms, for example Karlan and Valdivia (2009) randomize the provision of training for the owners of micro-enterprises in Peru, including some HRM training, and find some significant positive impact of sales and growth. Bruhn et al. (2010) provide management training for small firms in Mexico, and again find some evidence for significant improvements on a range of performance metrics. Bloom et al. (2009a) run experiments on large Indian firms to introduce a modern management practices, including modern HR practices around piece-rate pay for workers and pay for performance for managers, and find large effects on productivity and profitability. While this literature is at an early stage, the broad results are that introducing modern HRM practice into firms in developing countries leads to significant improvements in performance. It would clearly be helpful to have more such studies, and particularly in developed countries.

3.3 Econometric studies of the productivity impact of HRM

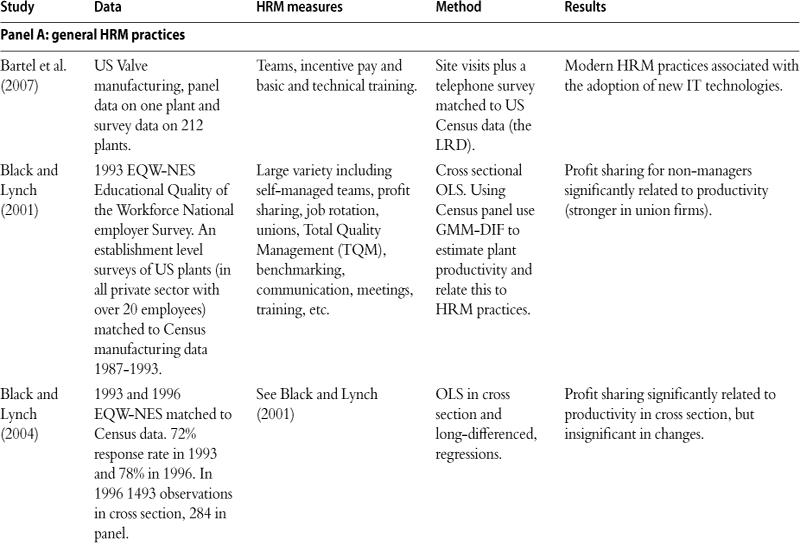

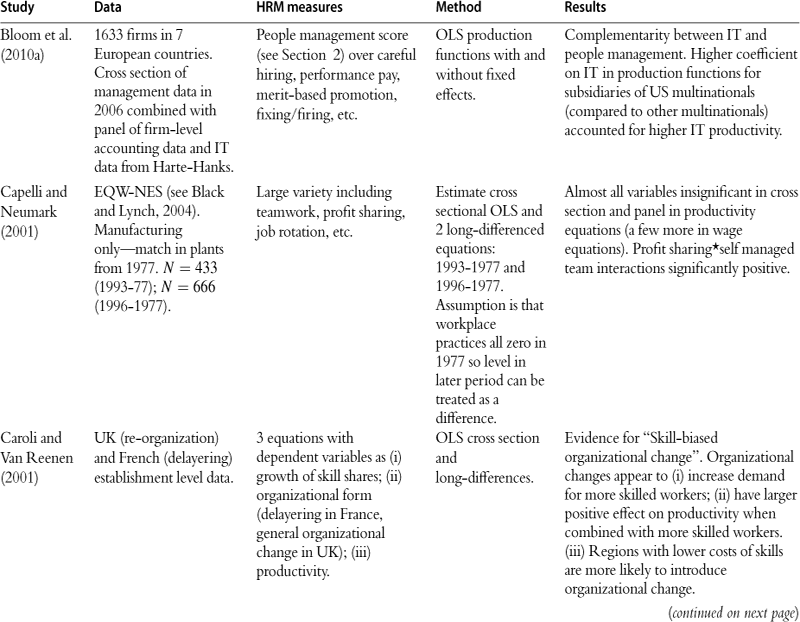

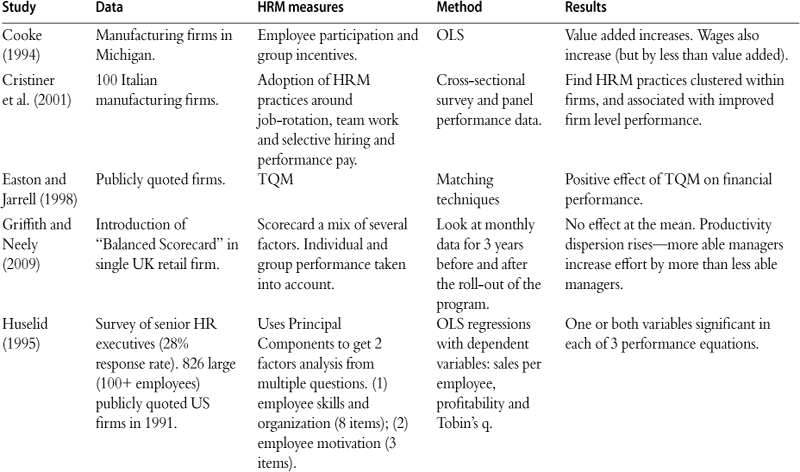

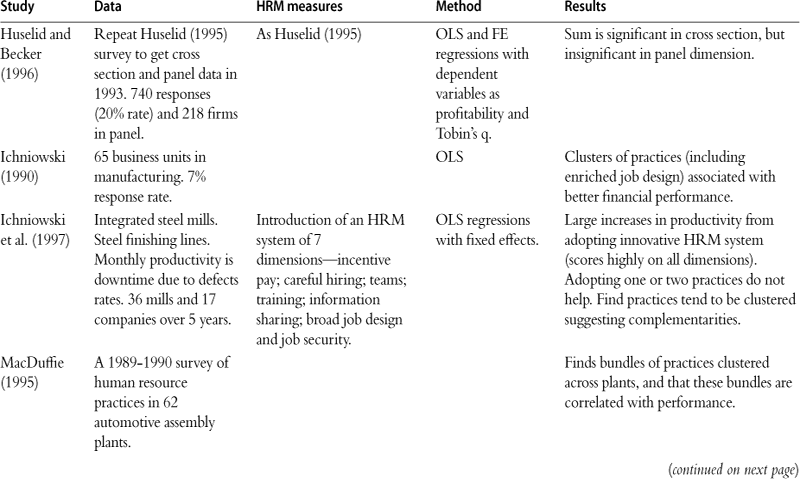

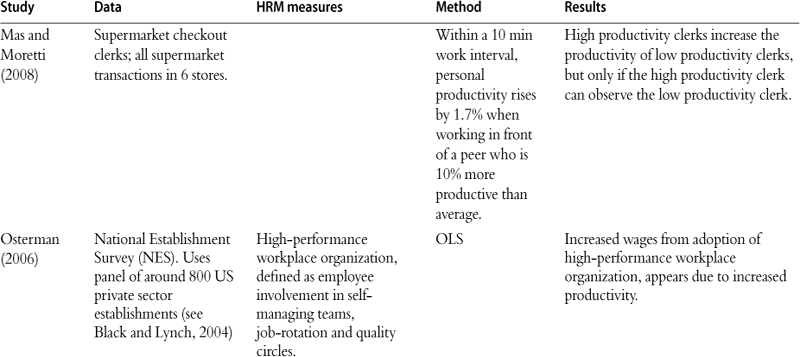

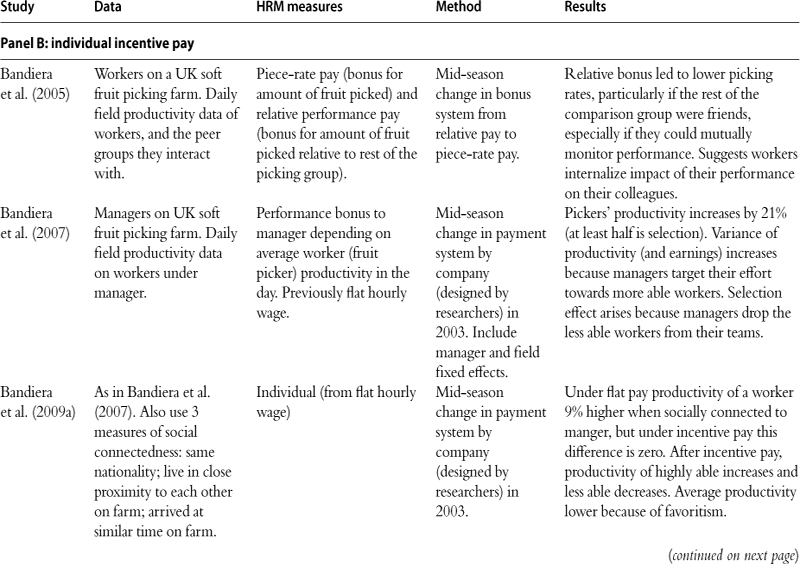

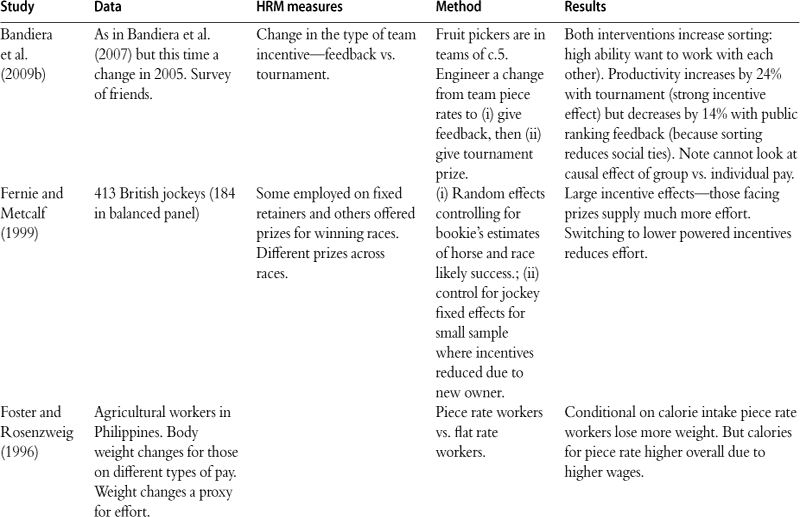

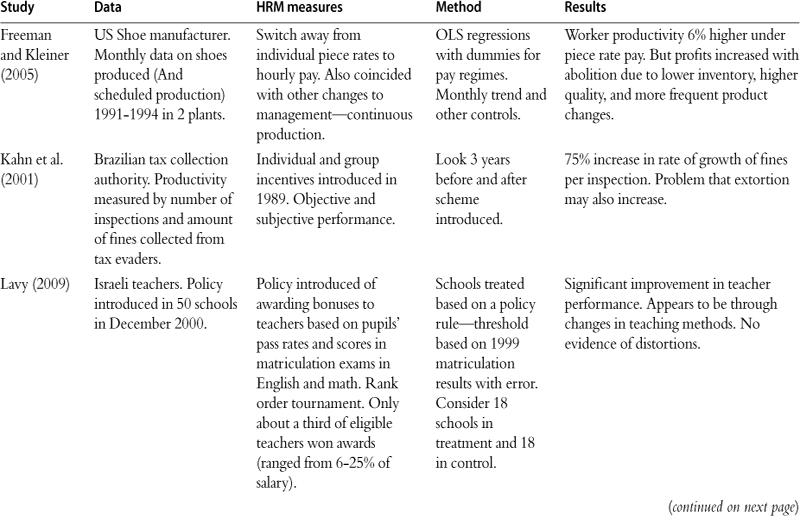

Having discussed the caveats in the previous sub-section, we now turn to the huge number of empirical studies on HRM and productivity which we attempt to summarize in Table 3.1. Before discussing these in detail, here is our four point summary.

1. First, high quality studies generally show that there is a positive effect on productivity of incentive pay, both individual bonuses and (more surprisingly) group bonuses. This seems true across many sectors, including the public sector (see, for example, the Prentice et al., 2007 survey).

2. Second, in addition to a pure incentives effect, there is usually also an important selection effect generating higher productivity—productivity increases because high ability workers are attracted to organizations offering higher powered incentives.

3. Third, the introduction of new forms of incentive pay is generally more effective when combined with other “complementary” factors. There are complements within the bundles of HRM practices (e.g. team work and group bonuses), and between some HRM practices and other firm characteristics (e.g. decentralization and information technology).

4. Fourth, there are many examples of perverse incentives, for example, when rewards are tied to specific periods of time (such as quarters) so that workers manipulate commissions to hit quarterly targets.

5. Fifth, incentive pay schemes tend to be associated with greater dispersion of productivity, as the effects are stronger on the more able workers, and this is stronger than the selection effect (which pushes towards reduced dispersion).

We divide this sub-section into general HRM studies (Panel A), individual incentive pay (Panel B), group incentive pay (Panel C) and distortions (Panel D).

3.3.1 General HRM studies

There are a huge number of studies that have correlated various aspects of the firm’s performance on various aspects of its HRM (recall Table 3.1 for some of the measures used). There is generally a strong and positive correlation between HRM and productivity.

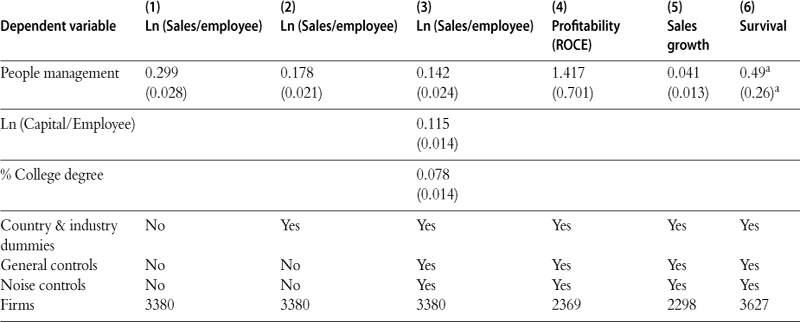

The better studies use micro data and pay careful attention to the measurement issues and need to control for many covariates. Black and Lynch (2001) examine various aspects of “high performance” workplaces including profit related pay, but also Total Quality Management, benchmarking, self managed teams, recruitment strategies, etc. This was from a rich cross sectional survey that they helped design (the EQW-NES) that could be matched to plant-level panel data from the Census Bureau. They estimated production functions controlling for conventional inputs such as labor, capital and materials, but also included a large number of these HRM practices. They found relatively few practices were significantly related to total factor productivity—profit sharing for non-managers and benchmarking were two of the stronger ones. The Bloom and Van Reenen (2007) management scores also show high correlations of HR management scores with labor productivity, as illustrated in the regressions in Table 3.2. A significant correlation is also apparent when other controls are added (columns (2) and (3)) or alternative measures of performance are used such as profitability, sales growth and firm survival (columns (4) through (6)). Of course none of these results are causal in the sense that cross-sectional correlations between HR and productivity may be driven by reverse causality, or correlations with other omitted factors as discussed above.

Table 3.2

Performance and people management practices.

All columns estimated by OLS with standard errors are in parentheses under coefficient estimates clustered by firm, except for column (6) which is estimated by Probit (we report marginal effects at the sample mean). Survival is defined as firms who are still in operation in Spring 2009 (including if they have been taken over by another firm). Sample of all firms with available accounts data at some point between 2000 and 2008. Management score has a mean of 2.973 and a standard-deviation of 0.664. “Country and industry dummies” includes a full set of 17 country and 162 SIC 3-digit dummies. “General controls” comprise of firm-level controls forln (average hours worked) and ln (firm age). “Noise controls” are 78 interviewer dummies, the seniority and tenure of the manager who responded, the day of the week the interview was conducted, the time of the day the interview was conducted, the duration of the interviews and an indicator of the reliability of the information as coded by the interviewer. All regressions include a full set of time dummies. “People Management” is the firm-level people management score covering pay, promotion, hiring, firing, retaining employees, consequence management and human capital targets. “% College Degree” is the share of employees with a college degree (collected from the survey). “Profitability” is ROCE which is “Return on Capital Employed” and “Sales growth” is the 5-year growth of sales. Survival is equal to zero if a firm exited due to bankruptcy/liquidation by the end of 2008 and one otherwise.

amarginal effect and standard error multiplied by 100. The sample mean of non-survival is 2.1% so the marginal effect of −0.49 implies one management point is associated with 23.5% (=0.49/2.1) lower exit rate.

Source: Authors’ calculations using Bloom et al. (2009b) data.

Some studies have tried to get a better handle on causation by using panel data on management practices to try and control for fixed cross-sectional differences between firms. In Black and Lynch (2004) the authors analyzed a second wave of the EQW-NES data so they could examine changes between 1996 and 1993. Again, some practices (such as profit related pay) showed up as informative in the cross section, but HRM practices were usually insignificant after controlling for fixed effects (only “re-engineering was significant). Capelli and Neumark (2001) come to a similar conclusion also examining the same data.

Since many of these practices appear to be highly correlated some researchers have aggregated them into a smaller number of summary measures. Huselid (1995) and Huselid and Becker (1996) did this in combining questions of his survey of HR managers into two principal components—”employee skills and organization” and “employee motivation”. They found that in the cross section one or other of these factors was positively and significantly related to productivity, profitability and Tobin’s Q. However, like Black and Lynch (2004), once fixed effects were included these factors were not significant.

The disappointing results for the absence of any “effect” in the time series dimension could be due to the fact that there genuinely is no relationship between productivity and HRM practices. Under this interpretation the cross sectional results are due to a spurious correlation with a time-invariant unobservable. Alternatively, there may be a downward endogeneity bias in the time-series, for example, because negative productivity shocks are positively correlated with the introduction of new practices. Nickell et al. (2001) argue that firms organizationally innovate when they are doing badly and this would cause such a downward bias. Another factor is measurement error, which if it is of the classical form can cause attenuation bias towards zero. This is likely to be particularly problematic for HRM practices if they do not change much over time and are measured with substantial error.

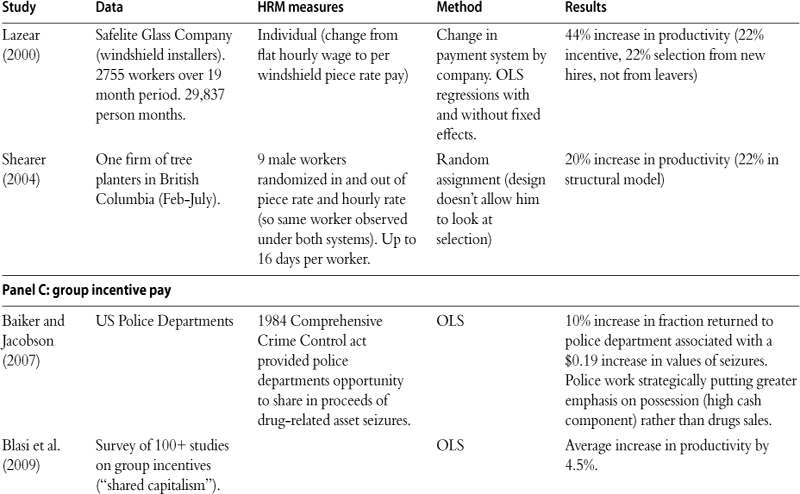

3.3.2 Individual incentive pay

A pioneering study is Lazear (2000) who looked at the replacement of a flat rate hourly pay system by a piece rate pay system for windshield installers in the Safelite Glass Company. In this firm each employee has a truck and drives to the homes of people who have broken car windshields and installs a new one. Looking 19 months before and after the introduction of the incentive pay plan, Lazear found that productivity increased by around 44% after the policy change, with about half of this due to selection effects and half from the same individuals changing their behavior. The selection effects are because less productive workers left the company and more productive workers joined, presumably attracted by the higher powered incentives.

More recently, Bandiera et al. (2007) engineered a change in the incentive pay system for managers in a UK fruit farm. All the workers (fruit pickers) were on piece rate pay, but prior to the policy change the managers were paid a flat rate, whereas afterwards there was a strong element of pay tied to the performance of the workers they managed. The average picker’s productivity rose by 21% after the introduction of performance related pay and at least half of this was due to improved selection. The remainder of the effect is due to managers focusing their efforts more on the workers where it had the greatest marginal effect. Examining the mechanism through which this happened, Bandiera et al. (2009a) gathered information on social connections from their survey. They found that prior to the introduction of incentive pay managers favored workers to whom they were socially connected, irrespective of the workers’ ability. After the introduction of performance bonuses they targeted their efforts towards high ability workers, regardless of whether they were socially connected or not. This had the effect of increasing the dispersion of productivity (as well as the level).

Freeman and Kleiner (2005) examine the elimination of piece rates for a US shoe manufacturer. They focused on two plants of the same firm who switched at different times and focused on what happened to productivity (monthly shoes produced per worker) and profits before and after the change in the pay scheme. Consistent with the other “insider” studies, productivity fell after the workers were put on a flat hourly rate. Interestingly, the authors show that profits rose after the change, which they attribute in part to improved quality with flat pay, plus a variety of other managerial changes complementary to flat rate pay.

A criticism of these studies is that the workers who are treated are not random. The firm who introduced the policy presumably believed there would be some benefits from doing so, thus it is hard to rule out the idea that there may have been some other contemporaneous change that affected worker productivity. Shearer (2004) addresses this problem in his study of tree planters in British Columbia. He worked with the company employing the planters and designed an experiment where all workers were randomly assigned to the incentive pay group for some days and flat hourly time rates for others (so the same worker is observed under both systems). He cannot look at selection effects, but found that the pure incentive effect was to increase productivity by around 22%, very similar to Lazear (2000).

Another example of cleaner identification is Lavy (2009), who exploits a quasiexperiment in Israeli schools where teachers were offered individual bonuses based on their relative performance as indicated by pupil scores in math and English exams. School assignment was based on a rule determined by past matriculation results, and this gives several identification methods including a regression discontinuity design around the threshold. He finds significant improvements in teacher performance and no evidence of distortions. Interestingly, the improvement in performance appeared to be due to changes in teaching methods and management. Not all evaluations of performance pay for teachers are so positive, although Lavy’s (2007) survey does suggest that the weight of evidence is in favor, and more so for individual incentive pay than for group incentives, which we turn to in the next sub-section.

In summary, these studies do suggest that individual incentive pay increases productivity. Other studies also show evidence that incentives affect employee behavior, but the precise “incentive effect” on productivity is not so easy to interpret10.

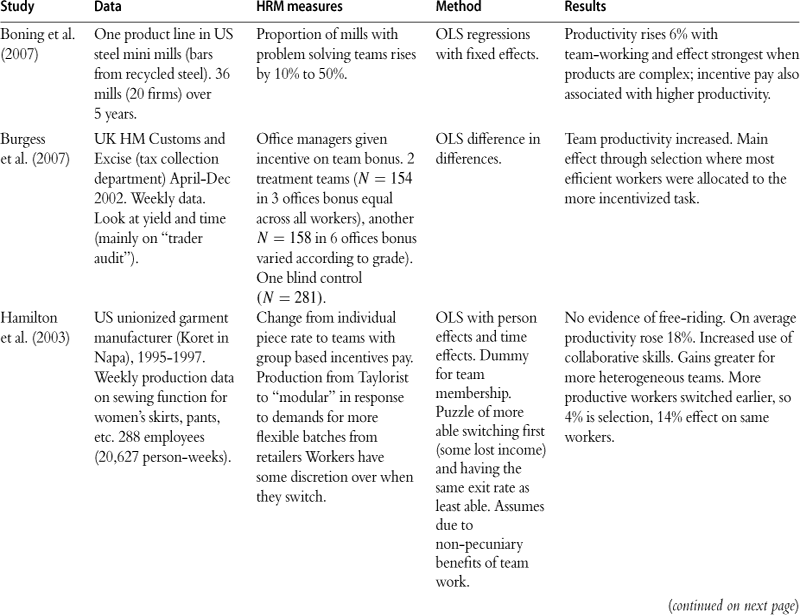

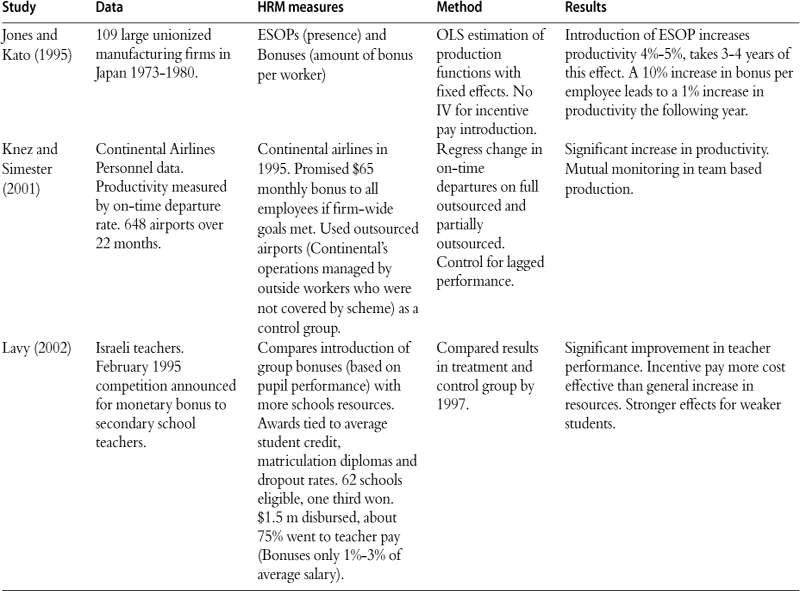

3.3.3 Group incentive pay

In Section 2 we saw that collective payment by results (such as team bonuses) has become much more important over the last 30 years or so. In the US almost half of employees participate in such schemes (see Section 2). There has been a recent review of the effects of such schemes in Blasi et al. (2009), who consider over 100 studies. In general a positive association is revealed between group incentive schemes and company performance, but with substantial diversity in results. The average estimated increase in productivity associated with employee ownership and profit sharing is 4.5%11. A survey of UK schemes by the UK Treasury (Oxera, 2007) found a mean effect across studies of 2.5% and larger effects for share ownership schemes12. Combinations of such schemes with other HRM practices were found to be particularly effective—e.g. employee involvement in teams.

A recent example of this literature would be Bryson and Freeman (2009), who use the 2004 UK WERS survey discussed in Section 2 to relate various measures of company performance to the presence of incentive pay. They find that employee share ownership schemes are associated with 3.3% high value added per worker compared to no other form of incentive pay, but other forms of group incentive pay are insignificant. As with most of the other studies, the problem is that there are many potential omitted variables that are not controlled for, so we are concerned whether this is a causal effect or simply an association with an unobservable13. Jones and Kato (1995) go one step further as they have panel data on ESOPs and bonuses in Japanese firms. Switches to ESOPS were associated with 4%-5% higher productivity after 3–4 years. Although panel data is an improvement, there is still the problem that the adopting firms are non-random, as discussed in Section 3.2.

Boning et al. (2007) examine the introduction of team-based systems (including group incentive pay) in a distinct product line across 36 mini-mills. These mini-mills take scrap metal and recycle it into steel bars used, for example, in freeways. They find team-based work (including team bonuses) are associated with 6% higher productivity, especially in more complex products, which indicates the importance of the complementarity between HRM and the wider strategy of the firm (see Section 3.4).

Hamilton et al. (2003) study the shift by a US garments manufacturer from individual pay towards group pay (“gain-sharing”). This coincided with a more general change in the firm’s production strategy to produce smaller more custom-made batches (reflecting demand from their major customer—retail clothing stores). This “modular” approach required more team work, so group bonuses were more appropriate incentives. Productivity rose by about 18%, and this increase was stronger for more heterogeneous teams. The authors suggest that this came from exploiting unused collaborative skills of workers. Surprisingly given the free rider problem, the more productive workers were earlier to switch. This suggests some non-pecuniary benefits and also positive peer effects (see below)14.

Boning et al. (2007) and Hamilton et al. (2003) have the advantage that some of the unobservable shocks are controlled for by focusing on a narrower group of individuals (working in a single industry or a single firm). Although they still face the issue of endogeneity, as there is no random assignment, their intimate knowledge of the change enables them to examine the mechanisms through which group pay influences productivity in a richer manner. Bloom et al. (2009a) do randomly assign firms to interventions including the introducing performance related pay and find a 10% improvement in productivity.

Burgess et al. (2007) obtain something that is closer to random assignment by examining the introduction of a group incentive system in the UK tax collection agency. The preliminary results from this work suggest that group bonuses were effective in significantly raising productivity. Also in the public sector, Lavy (2002) finds that group bonuses for Israeli school teachers were highly effective in raising performance (compared to simply increasing school resources). Schools were given awards for improvements in dropout rates, matriculation rates and credits. The effects were stronger for weak students. Finally, Baiker and Jacobson (2007) find that group incentives in the form of keeping a greater share of the value of seized assets caused police productivity to rise in catching drug offences.

In summary, there does then, appear to be evidence that group incentive schemes also raise productivity, which is surprising given the free rider problem. Overall, in our opinion, however the evidence is weaker here than that for individual incentive pay.

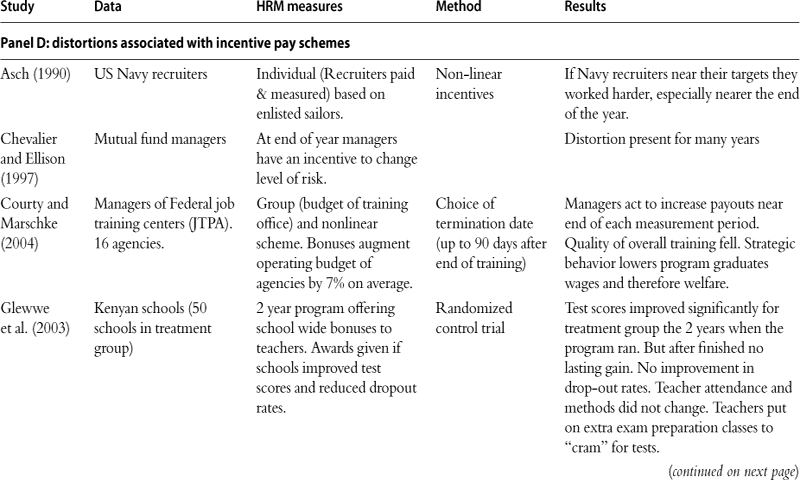

3.3.4 Distortions due to incentive pay

The studies in the previous sub-sections suggested that individuals do respond to pay incentives and generally in a way that usually increases productivity. The theoretical literature has emphasized many ways in which incentive pay can cause distortions which could reduce productivity. First, employees are more risk averse than firms and incentive pay increases the risks faced by workers. Thus it may discourage some high ability (but risk averse) workers from joining the firm and encourage excessive risk taking15. Second, firms cannot always credibly commit to reward performance ex post. For example, Gibbons (1987) details a model where only the worker knows the difficulty of job and the true action. He shows how this generates a “ratchet effect” where workers will restrict output unless the employer can commit not to use the information it obtains from learning the difficulty of the task. Third, measures of the worker’s productivity are imperfectly related to inputs (worker effort). Baker (1992) shows how incentive pay tied to a measurable output will cause workers to increase effort to improve the measured output and reduce effort on the unmeasured output (e.g. quantity instead of quality in Lazear, 1986)16.

Given the difficulty with tying incentives to objective measures what about the common practice of using supervisors’ subjective measures of performance? Several papers have modeled the optimal mix of incentives based on imperfect objective measures and perfect (but unverifiable) subjective measures17. The problem with subjective measures is that, although they provide stronger incentives, workers have to trust that the firm does not renege ex post, which is a particular danger with unverifiable information. Furthermore, there will still be the problem of the gap between actual and measured effort. This can mean (i) employees engage in “influence activity” to alter supervisors’ decisions in their favor (e.g. Milgrom and Roberts, 1988)18; (ii) there may be favoritism on the behalf of supervisors for particular workers (Prendergast and Topel, 1996)19; (iii) the supervisor and employee may hold different opinions about employee’s performance (MacLeod, 2003).

Empirical work has tended to focus on the potential distortions in explicit incentive schemes. One key distortion that occurs is the measurement period. Asch (1990) examines US Navy recruiters who were incentivized based on their ability to enlist sailors (partly through measurement and some also through explicit payments). This was based on annual quotas, so only affected those who were close to missing their quota. In addition, the effect was extremely strong near year end, but weak afterwards, causing inconsistent efforts over time. Courty and Marschke (2004) analyze managers of job training centers and show that managers work very hard at the end of the measurement period, but generated some costs in the form of lower training quality. Glewwe et al. (2003) examined a school-wide incentives program in Kenya. The program randomly assigned fifty elementary schools to a treatment group eligible for monetary incentives (21%-43% of monthly salary). All teachers in winning schools received rewards based on average test score performance and dropout rates. Student scores improved significantly in the treatment schools for the two years the program was in place. But this appeared to be due solely to teachers conducting test preparation outside of regular class and there were no long-run effects on pupil performance. This appeared to be a classic case of incentives simply causing “teaching to the test”.

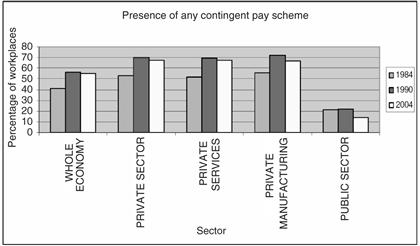

One might think that since these are examples from the public sector it is no surprise that incentives are poorly designed. Yet there are also many private sector examples. Oyer (1998) shows that firms typically build incentives around fiscal years. Consequently, firms sell more (at lower margins) near the end of the fiscal year compared to the middle of the year, and even less just at the start of the accounting year. Larkin (2007) looks at a large software company and shows that salesmen acted on their incentives to shift effort towards the end of their measurement period. Compared to the counterfactual of no incentive contracts it is unclear whether these imperfect incentive contracts reduce overall productivity (although Larkin argues that there is a 6%-8% cost in potential revenue)20.

A more subtle form of distortion can occur between types of individual incentive pay systems when workers have social preferences. Many economists (e.g. Lazear, 1989) have puzzled over why relative performance benchmarks are not used more commonly in pay systems given their desirable properties (i.e. common time specific shocks outside the employees’ control are removed). Bandiera et al. (2005) examined a change of incentive pay among workers in their firm from a system based on relative performance to piece rates based on absolute performance. They found that productivity increased by 50% as a result of the experiment and attributed this to the fact that workers have social preferences (using their measures of friendship networks). Under a relative performance system a worker who increases his effort puts a negative externality on other workers under a relative system, but has no such affect under a piece rate system.

Overall, there is clear evidence that distortions often occur in response to incentive pay schemes, especially when badly designed. Nevertheless, the evidence that many performance pay schemes—whether individual or group—can raise productivity suggests that these distortions are not generally overwhelming.

3.3.5 Labor unions

A related literature is on the productivity impact of labor unions, an important human resource policy choice (see Freeman and Medoff, 1984). One recent attempt at an identification strategy here is DiNardo and Lee (2004), who exploit a regression discontinuity design. In the US a union must win a National Labor Relations Board election to obtain representation, so one can compare plants just above the 50% cut-off to plants just below the 50% cut-off to identify the causal effects of unions. In contrast to the rest of the literature, DiNardo and Lee (2004) find no effect of unions on productivity, wages and most other outcomes. The problem, of course, is that union effects may only “bite” when the union has more solid support from the workforce.

More generally, there is the question of whether unions inhibit incentive pay. Arguments can be made both ways. Although Fig. 2.1 is suggestive of the rise in incentive pay moving in the opposite way to the fall in union power, and unions are certainly associated with lower pay dispersion within firms, Brown (1990) found no relationship with performance pay.

3.4 Complementarities

One of the key reasons why firms may find it difficult to adjust their organizational form is that there are important complementarities between sets of organizational practices. Milgrom and Roberts (1990) build a theoretical structure where such complementarities (or more precisely, super-additivities) mean that firms optimally choose clusters of practices that “fit together”. When the environment change so that an entrant firm would use this group of optimal practices, incumbent firms will find it harder—they will either switch a large number together or none at all.

This has important implications for productivity analysis. The effects of introducing a single practice will be heterogeneous between firms and depend on what practices they currently use. This implies linear regressions of the form of Eq. (1) may be misleading. To see this, consider that rather than a single HRM practice (dit) there are two management practices, m1 and m2 and their relationship with productivity is such that TFP (the yu considered here) increases by more when they are used together.

![]() (4)

(4)

A simple version of the complementary hypothesis is βi2 > 0. A stronger form is that the disruption caused by just using one practice alone actually reduced productivity, βl < 0, β2 < 0. In this case a regression which omits the interaction term may actually only find only a zero coefficient on the linear terms.

The case study literature emphasizes the importance of complementarities. Econometrically, testing for their existence poses some challenges, however, as pointed out most clearly by Athey and Stern (1998). A common approach is a regression of practice 1 on practice 2 (and more) with a positive covariance (conditional on other factors) indicating complementarity. It is true that complements will tend to co-vary positively, but this is a very weak test. There could be many other unobservables causing the two practices to move together. Essentially, we need instrumental variables for at least one of the practices (e.g. Van Biesebroeck, 2007), but this is hard to obtain as it is unclear what such an instrument would be—how could it be legitimately excluded from the second stage equation? In classical factor demand analysis we would examine the cross price effects to gauge the existence of Hicks-Allen complements versus substitutes, i. e. does demand for practice 1 fall when the price of practice 2 rises (all else equal). Analogously, we would like to observe some cost shock to the adoption of practice 1 that is uncorrelated with the error term in the practice 2 adoption equation. Unfortunately, such tests are particularly hard to implement because there are generally no market prices for the organizational factors we are considering.

An alternative strategy is to work straight from the production function (or performance equation more generally). In an influential paper Ichniowski et al. (1997) estimate a version of Eq. (4) using very disaggregate panel data on finishing lines in integrated US steel mills using eleven human resource practices (including incentive pay, recruitment, teamwork, job flexibility and rotation). Their measure of productivity is based on downtime—the less productive lines were idle for longer. They find that introducing one or two practices has no effect, but introducing a large number together significantly raises productivity. Although the endogeneity problem is not eliminated, the controls for fixed effects, looking at very disaggregated data and a performance measure suited to the sector (downtime) helps reduce some of the more obvious sources of bias. Gant et al. (2002) show that the productivity benefits of team working in steel plants appear to be due to faster problem solving because of tighter horizontal interactions and networks between workers. They use detailed surveys of who is talking to who to show that plants involved with innovative HRM systems have this feature.

In addition to endogeneity concerns, there is a further problem with interpreting a positive estimate of βi2 in Eq. (1) as evidence of complementarities. The true model may be one where there is a single latent factor for “good HRM management” and the many individual HRM measures may be (noisy) signals of this latent factor. This will generate positive covariance between the practices and could also cause the interaction to be positive. Thus, some care is required in the interpretation of the production function coefficients.

We have focused on complementarities between types of HR practices. New technology is often discussed in this context and we turn to this next (see also Section 5).

3.5 The role of information and communication technologies (ICT)

One of the key productivity puzzles of recent years has been why the returns to the use of information and communication technologies appear to be so high and so heterogeneous between firms and between countries. For example, Brynjolfsson and Hitt (2003) find that the elasticity of output with respect to ICT capital is far higher than its share in gross output (see also Stiroh, 2004). This reversed the well known Solow Paradox that one could find computers everywhere except the productivity figures. Not only was there evidence for large and significant returns at the micro-level, US productivity growth accelerated at the macro level from 1995 onwards. A substantial fraction of this appears to be linked to the production and use of ICT (e.g. Jorgenson et al., 2008), and the greater pay-off to ICT usage seems to be a reason why European productivity growth was much slower than that in the US since the mid 1990s (ending the catching up process).

One explanation for these phenomena was that effective use of ICT also requires significant changes in firm organization. Changing the notation of (5) slightly we could write

![]() (5)

(5)

where c is ln(ICT capital) and m is an HRM practice. The hypothesis that βcm > 0 would be consistent with complementarity between some HRM practices and ICT. Bresnahan et al. (2002) try to test this directly by surveying the organizations of large US firms on decentralization and team work (for a cross section) and combining this with data on ICT (from a private company Harte-Hanks) and productivity from Compustat. They find evidence that βcm > 0. Bloom et al. (2010a) broaden the sample to cover firms in seven European countries and find evidence of complementarity of ICT with the Bloom-Van Reenen measure of HR management discussed in Section 2. They also show that their results are robust to controlling for firm fixed effects. Careful econometric case studies (e.g. Baker and Hubbard, 2004; Bartel et al., 2007) also identify differential productivity effects of ICT depending on organization form. We will return to the issues of complementarity between HRM, technology and human capital in Section 5.

4 Two perspectives on hrm and productivity: design and technology

In thinking about the reasons for variations in HRM and productivity a contrast can be drawn between two possible approaches. The first is the now classic approach of Personnel Economics, which we label the “design” approach. The view here is that the HRM practices we observe are chosen and continuously optimized by a profit maximizing firm: they are explicit strategic choices of the firm, and observable variations in HRM reflect variations in the firm’s environment.

A second approach is becoming more common, but has not been closely linked to labor economics. We label this the “managerial technology” approach because of the recent stress in diverse fields of economics, such as trade, public and macro, but above all Industrial Organization, that there are large and persistent differences in firm productivity (see Section 2.2 above). In this view some aspects of HRM could be considered as a technology or “best practice” in the jargon. Adopting these forms of HRM would improve productivity in a typical firm. This leads on naturally to the question of why all firms have not adopted such practices. We discuss this below, but one immediate explanation is that all technologies have some diffusion curve whereby not all firms immediately adopt them. For example, it took American car manufacturers decades to accept and then implement Japanese style “lean manufacturing” techniques pioneered by Toyota. Informational constraints (and other factors we discuss below) could be an explanation for the slow diffusion of major managerial innovations.

The firm heterogeneity inherent in the managerial technology perspective mirrors the traditional labor economist’s emphasis on heterogeneity amongst workers. Interestingly, the many recent contributions in labor economics have found that fundamental features of the labor market such as the persistent dispersion in equilibrium wage distribution for similar workers cannot be easily understood without appealing to some sort of firm heterogeneity (e.g. Postel-Vinay and Robin, 2002; Cahuc et al., 2006). Such models are generally silent on how this firm heterogeneity comes about, but their existence seems important in quantitatively matching features of wage dispersion in real labor markets.

The Design and Technology perspectives are not mutually exclusive, of course. As economists, we believe that there is always some element of maximization. The managerial technology perspective highlights, however, that some firms are constrained by being less productive than others. We believe that this is an important empirical phenomenon which can explain many puzzling facts and requires integration into the dominant design paradigm. We overview both perspectives and refer readers who want more depth to the surveys in Gibbons and Waldman (1999), Malcomson (1999), Prendergast (1999), Lazear (1999) and especially Lazear and Oyer (forthcoming) which summarizes the most recent theory and some more recent empirical evidence.

4.1 The design perspective

The economics of contracts (see Bolton and Dewatripont, 2005, for an overview) and the economics of organizations (see Gibbons and Roberts, forthcoming) have made huge strides in recent decades. HRM or Personnel Economics is a sub-class of this broader field with a focus on explaining the type of institutions we observe in real employment contracts and organization.

Prior to the emergence of Personnel Economics, the study of HRM was dominated by industrial psychologists and sociologists, who emphasized institutions and culture as determining the internal organization of firms. Generalizations were eschewed. Traditionally labor economists focused on labor demand and supply, unemployment and investment in education, issues that saw the firm as a single unit rather than a complex organization and so had little to directly say on the structure of pay, promotions and design of work within firms. This started changing in the 1970s, partly as new techniques of agency and contract theory allowed a more systematic treatment of activity inside companies.

The design perspective borrows three key principles from economics. First, firms and workers are rational maximizing agents (profits and utility respectively). Secondly, it is assumed that labor and product markets must reach some sort of price-quantity equilibrium, which provides some discipline for the models. Finally, the stress is very much on private efficiency, with an emphasis on why some employment practices which may look to be perplexing and inefficient on the surface (e.g. mandatory retirement and huge pay disparities for CEOs) may actually be (at least privately) optimal.