Great Expectations: Law, Employment Contracts, and Labor Market Performance

W. Bentley MacLeod1, Columbia University, Department of Economics, 420 West 118th, MC 3308, New York, NY 10027–7296, USA, [email protected]

Abstract

This chapter reviews the literature on employment and labor law. The goal of the review is to understand why every jurisdiction in the world has extensive employment law, particularly employment protection law, while most economic analysis of the law suggests that less employment protection would enhance welfare. The review has three parts. The first part discusses the structure of the common law and the evolution of employment protection law. The second part discusses the economic theory of contract. Finally, the empirical literature on employment and labor law is reviewed. I conclude that many aspects of employment law are consistent with the economic theory of contract— namely, that contracts are written and enforced to enhance ex ante match efficiency in the presence of asymmetric information and relationship specific investments. In contrast, empirical labor market research focuses upon ex post match efficiency in the face of an exogenous productivity shock. Hence, in order to understand the form and structure of existing employment law we need better empirical tools to assess the ex ante benefits of employment contracts.

JEL classification: J08; J33; J41; J5; K31

Keywords: Employment law; Labor law; Employment contract; Employment contract Law and economics

“Now, I return to this young fellow. And the communication I have got to make is, that he has great expectations.”

Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

“Take nothing on its looks; take everything on evidence. There’s no better rule”“

Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

1 Introduction

New jobs and relationships are often founded with great expectations. Yet, despite one’s best efforts, jobs and relationships may end prematurely. These transitions might be the result of an involved search for better opportunities elsewhere, or in the less happy cases they may stem from problems in the existing relationship. These endings can be difficult, especially when parties have made significant relationship-specific investments. The purpose of this chapter is to review the role that employment and labor law play in regulating such transitions. This body of law seeks a balance between the need to enforce promises made under great expectations and the need to modify those promises in the face of changed circumstances.

The chapter’s scope complements the earlier chapter on labor-market institutions in Volume 3 of this handbook by Blau and Kahn (1999). That chapter focused on policies affecting wage-setting institutions. Like much of modern empirical labor economics, Blau and Kahn (1999) use the competitive model of wage determination as the central organizing framework. Economists begin with the competitive model because it provides an excellent first-order model of wage and employment determination. The competitive model assumes that wages reflect the abilities of workers as observed by the market; this information, combined with information about a worker’s training, provides sufficient information for the efficient allocation of labor.

Even if a labor market achieves production efficiency, it may nevertheless result in an inequitable distribution of income, as well as inadequate insurance for workers against unforeseen labor shocks. A number of institutions—such as a minimum wage, unions, mandated severance pay, unemployment insurance, and centralized bargaining— are viewed as ways to address these inequities and risks. Given that a competitive market achieves allocative efficiency, then these interventions necessarily result in allocative inefficiency. Hence, the appropriate policy entails a trade-off between equity and efficiency. For example, Lazear (1990) views employment law as the imposition of a separation cost upon firms wishing to terminate or replace workers. From this perspective, the policy issue is whether or not the equity gains from employment law are worth the efficiency costs. Many policymakers, such as the OECD and the World Bank, have taken the view that these employment regulations have for the most part gone too far—that they restrict the ability of countries to effectively adjust to economic changes and make workers worse off in the long run.2

Notwithstanding the mainstream skepticism toward efforts to regulate the employment relationship, it remains true that some form of employment law has operated in every complex market society for at least the last 4000 years—for example, the first minimum wage laws on record date back to Hammurabi’s code in 2000 BC. This chapter therefore takes a somewhat different perspective, drawing upon the literature in transaction-cost economics pioneered by Coase (1937), Simon (1957) and Williamson (1975), as well as the work on law and institutions by Posner (1974) and Aoki (2001). This research on the economics of institutions, like empirical labor economics, begins with the hypothesis that long-lived institutions are successful precisely because they are solving some potential market failure. Accordingly, this chapter is organized around the following question: How can labor-market institutions be viewed as an efficient response to some market failure? Just as the competitive-equilibrium model supposes that wages are the market’s best estimate of workers’ abilities, the institutional-economics program views successful institutions as solving a resource-allocation problem.

This approach does not assume that these institutions are perfect. On the contrary, just as the competitive model yields predictions regarding how wages and employment respond to shock, the hypothesis that institutions efficiently solve a resource-allocation problem generates predictions regarding the rise and fall of these institutions. Important precursors to this approach are found in labor economics. In a classic paper, Ashenfelter and Johnson (1969) suggest that we should be able to understand union behavior, including the strike decision, as the outcome of the interaction between several interested parties. The work of Card (1986) demonstrates that observed contracts cannot be viewed as achieving the first best, and hence transaction costs are a necessary ingredient for understanding the observed structure of negotiated employment contracts. Despite this early progress, the literature I review is still undeveloped. We do not have a good understanding of how the law works, nor do we understand the impact of legal rules on economic performance. In an effort to summarize what is known, this review is divided into three sections that correspond to coherent bodies of research.

Section 2 briefly reviews the structure of employment law and discusses some exemplary cases. A full review of employment law is not provided—for an excellent review, see Jolls (2007). My more modest goal is to provide some relevant insights into what law is and how it works. This sort of targeted inquiry is desirable because the standard assumption in economics is that the law enforces contracts as written. In practice, private law imposes no restrictions on behavior. It is mainly an adjudication system that can, after a careful review of the evidence, exact monetary penalties upon parties who have breached a duty. Hence, private law is a complex system of incentive mechanisms that affects the payoffs of individuals but does not typically constrain their choices. The distinction is important for economics because it is convenient to model legal rules as hard constraints on behavior—that is, as structuring the available moves in a game rather than just altering some of the expected payoffs. This approach also implies, wrongly, that rules apply equally to all individuals. Treating private law as an incentive system, instead, implies that the impact of the law is heterogeneous—an individual’s response to a legal rule will vary with an individual’s characteristics, such as wealth, attitudes toward risk, and the evidence that one can present in court.

Heterogeneity and information also play key roles in the theory of employment contracts reviewed in Section 3. The past forty years have witnessed tremendous progress in the economic theory of contract, especially in terms of teasing out how a particular set of parties should design a contract given the transaction costs characterizing the employment relationship. The influential principal-agent model, for example, was developed in the context of the insurance contract, which specifies state-contingent payments.3 The modern theory of contract, building on the work of Grossman and Hart (1986), recognizes that an important function of economic institutions and contracts is the efficient allocation of authority and decision rights within a relationship.

Most economists agree that unions and employment law affect the relative bargaining power of individuals. These institutions are usually interpreted as mere re-distribution of rents, and so any allocation of bargaining power that results in prices diverging from competitive levels is inherently inefficient. The modern literature on contract views authority as an instrument for mitigating transaction costs due to asymmetric information and holdup. This perspective also naturally admits a role for fairness in decision-making, and hence can provide an economic rationale for why fairness concerns are important in the adjudication of a dispute.4

Section 3 also discusses the empirical content of these models. The modern empirical literature is concerned with identifying a causal link between various labor-market interventions and performance. Unfortunately, much of the economic theory of contract is not amenable to this approach. These models typically describe how matches with certain observable features (X variables) result in an employment-compensation package (Y variables). As Holland (1986) makes clear, these are not causal relationships, but merely associations. For example, the predicted relation between the sex of a worker and the form of his/her employment contract is not causal, since the sex of a worker is not a treatment variable.

This distinction is useful because it helps explain the gulf between much of the theory discussed in Section 3 and the empirical evidence discussed in Section 4. It is also worthwhile to keep in mind that all economic models are false. This does not imply that these models are not useful. As Wolfgang Pauli quipped regarding a paper by a young colleague – “it’s not even wrong!”5 Rather, economic models are decision aids that guide further data collection and help in selecting between different policy interventions. The upshot for empirical researchers is that one typically tests the associations that the theory predicts, rather than the theory itself. Empirical determinations of the validity of these associations can help us decide whether and to what extent we can rely on the model as a decision aid.

The theory section discusses how contract theory can be used to understand employment law, and the conditions under which it may be desirable. We begin with a discussion of how contract design is affected by the interplay between risk, asymmetric information and the holdup that arises from the need for parties to make relationship specific investments. These models can be used to explain the role of the courts in enforcing the employment contract. The recent property rights theory of the firm developed by Grossman and Hart (1986) illustrates the importance of governance and the associated allocation of decision rights in order to achieve an efficient allocation.6 A contract is an instrument that explicitly allocates certain decision rights between the contract parties. This can also be achieved with unions. This section discusses how the appropriate allocation of power and decision rights can enhance productive efficiency. Thus, these theories provide conditions under which union power may enhance productive efficiency, as suggested by Freeman and Medoff (1984).

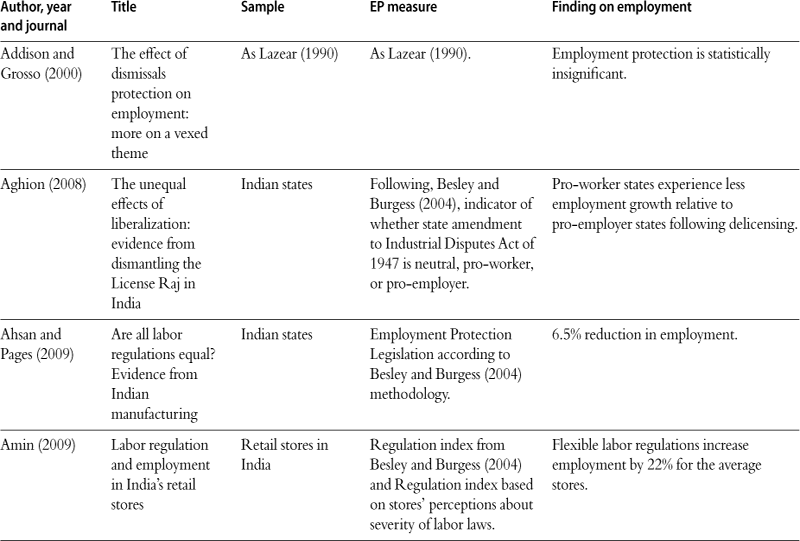

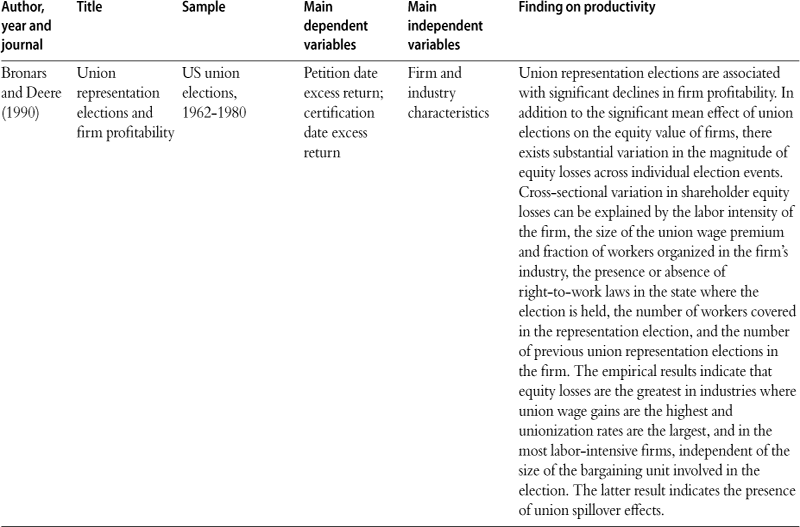

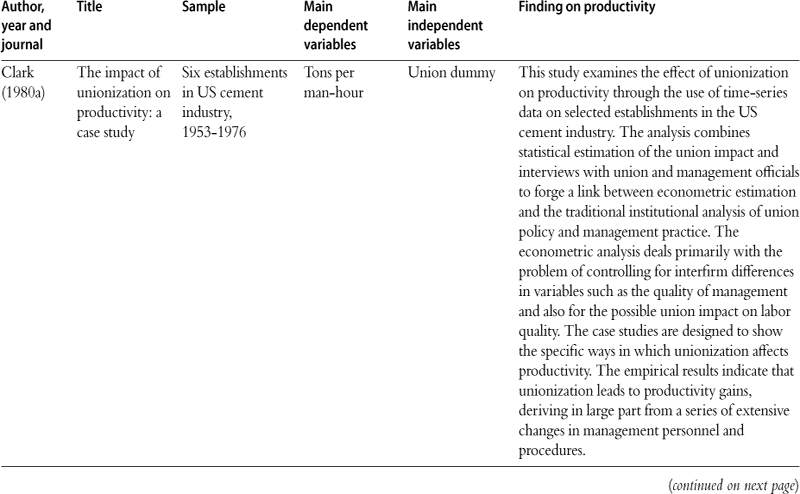

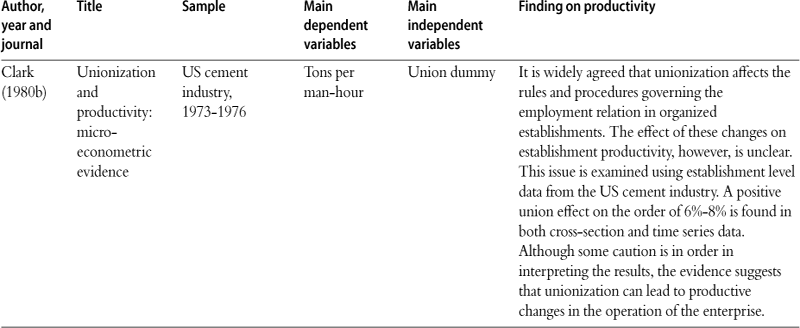

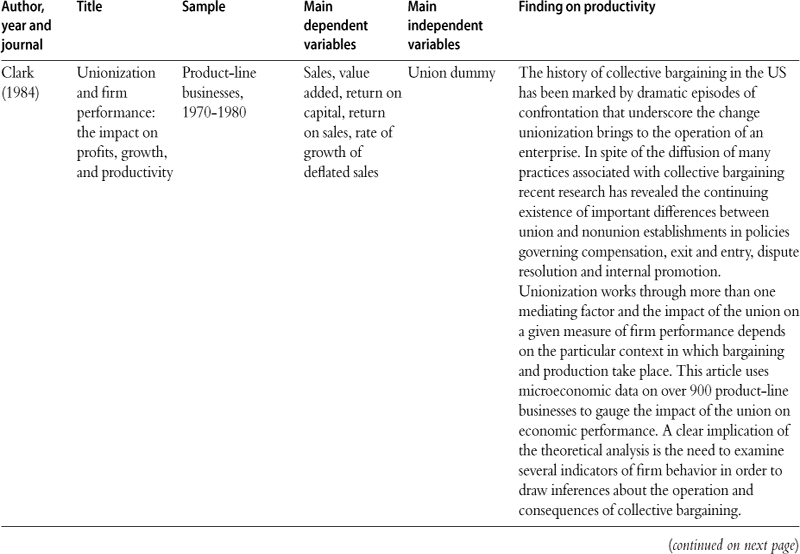

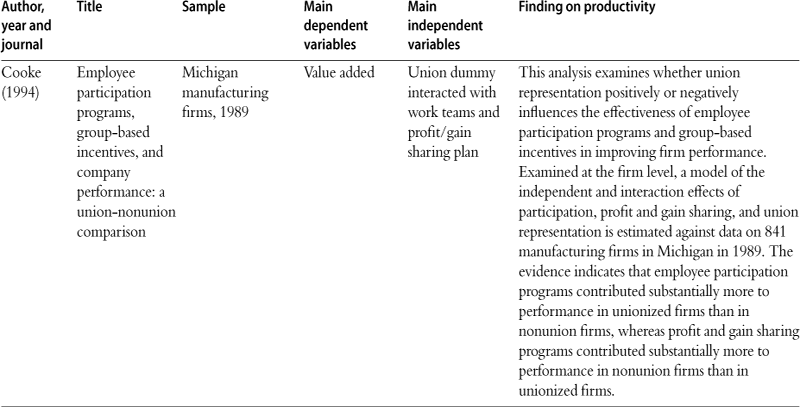

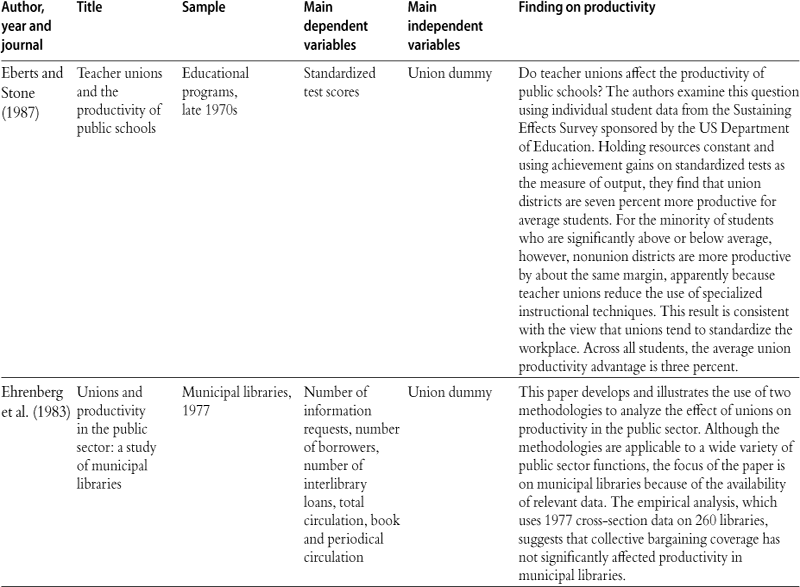

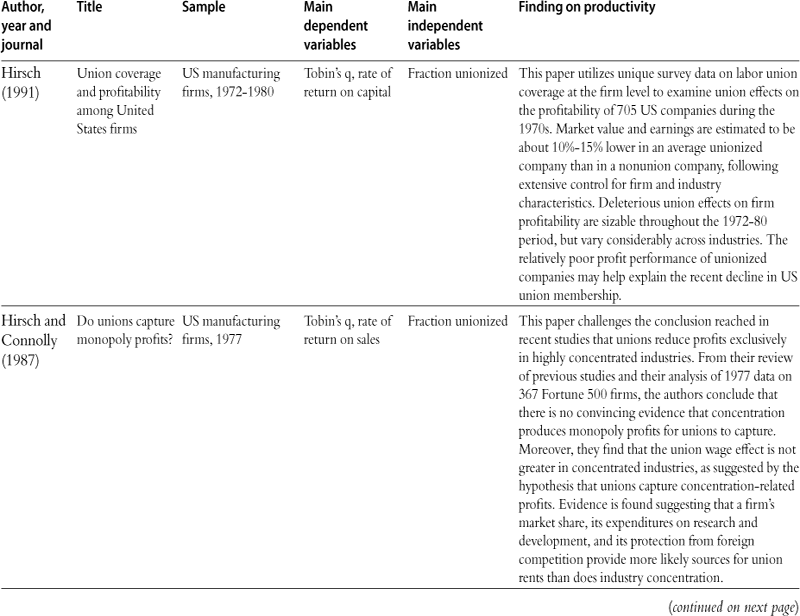

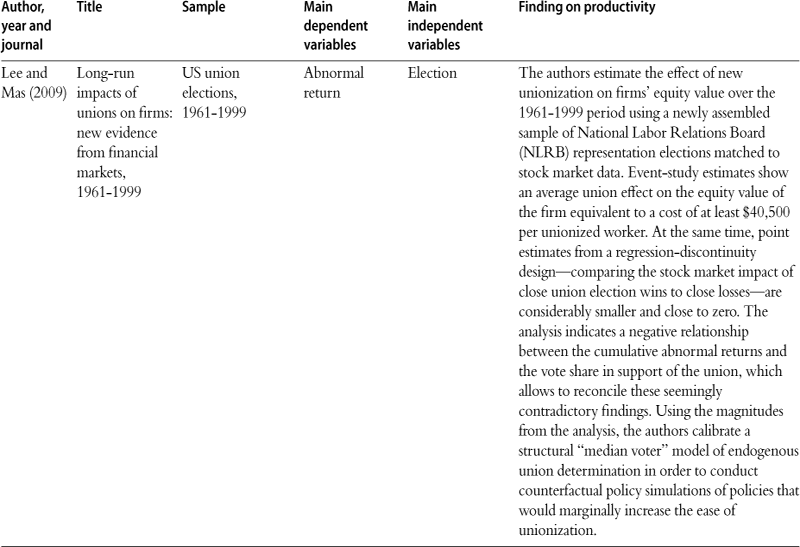

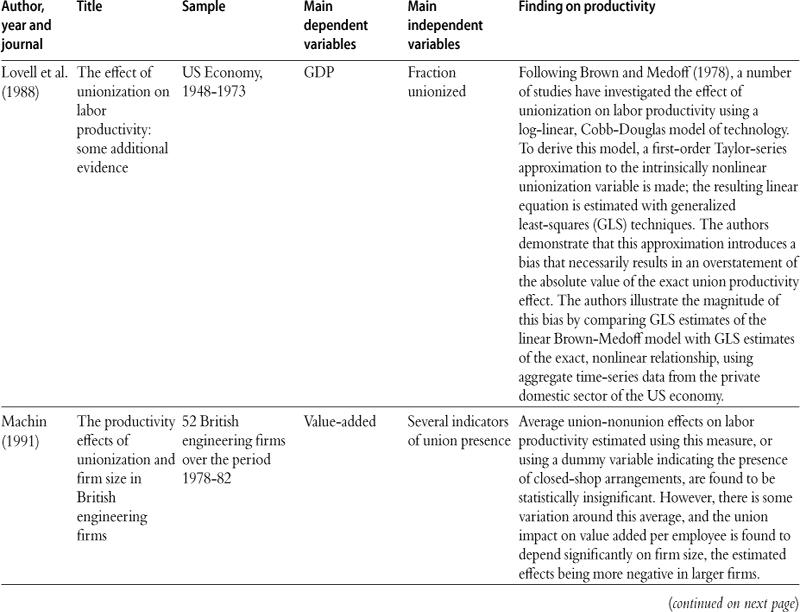

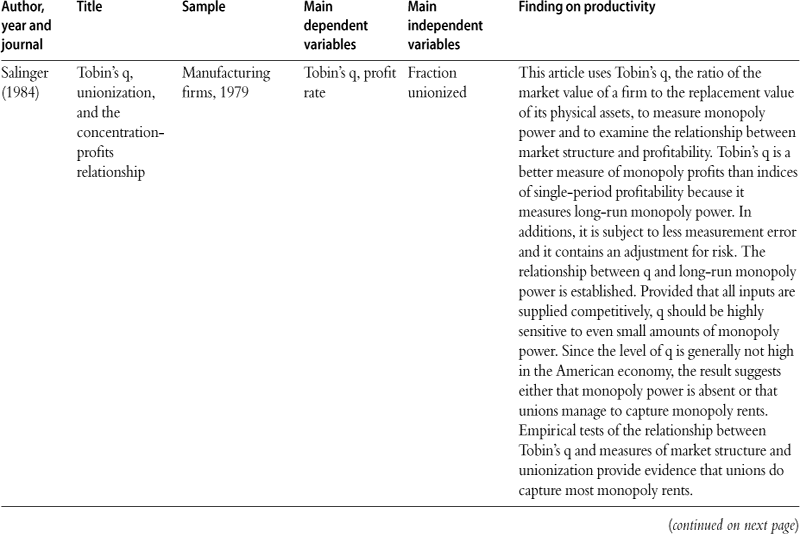

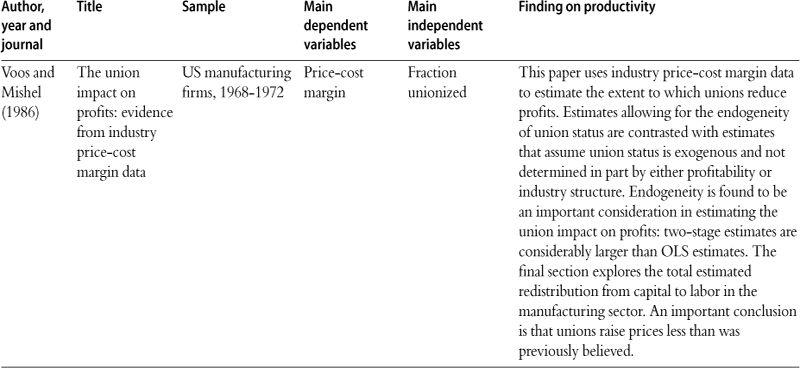

Section 4 reviews the empirical evidence on employment and labor law. Here we are concerned with explicitly causal statements such as the question of whether or not a reduction in dismissal barriers will reduce unemployment. This is a causal inquiry because it compares the outcomes from two different choices: having more or less employment protection law. Section 4.2 discusses the literature on unions that addresses two questions. First, does unionization of a workforce increase productive efficiency? Second, does unionization increase or decrease firm profits? Even if a union increases productive efficiency, if the increase in rents extracted by the unions is greater than the increase in productive efficiency, then profits would fall as a consequence, which in turn may lead to a decrease in unionization. The chapter concludes with an assessment of the evidence and a discussion of future directions for research.

2 The law

‘“The law embodies the story of a nation’s development through many centuries, and it cannot be dealt with as if it contained only the axioms and corollaries of a book of mathematics. Inorder to know what it is, we must know what it has been, and what it tends to become”“

Oliver Wendell Holmes, The Common Law, 1881

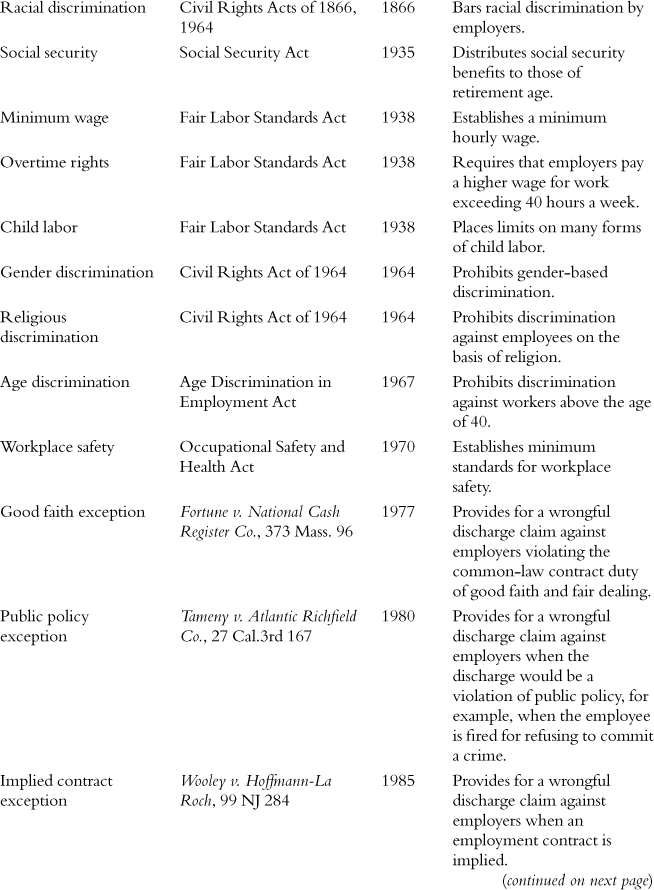

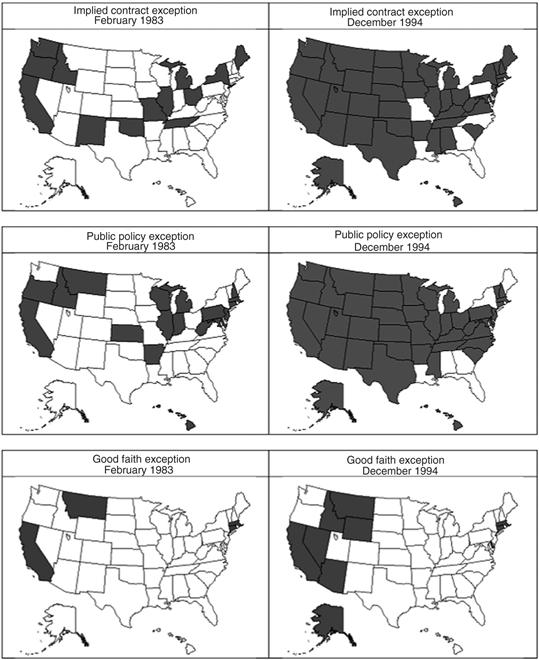

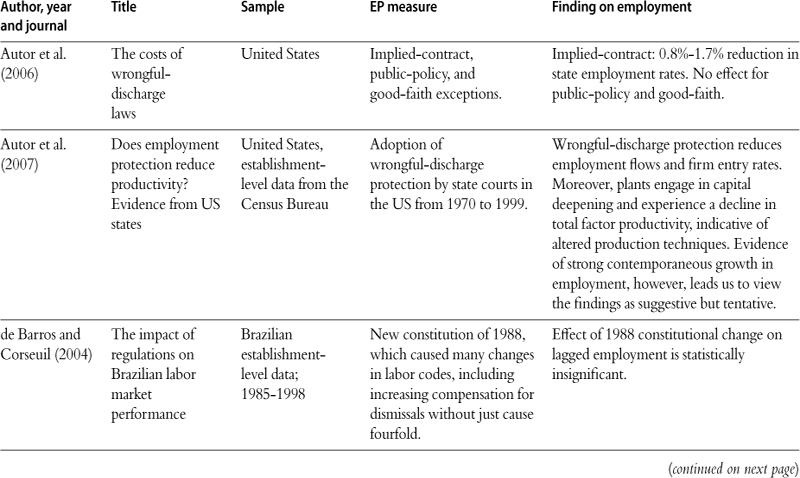

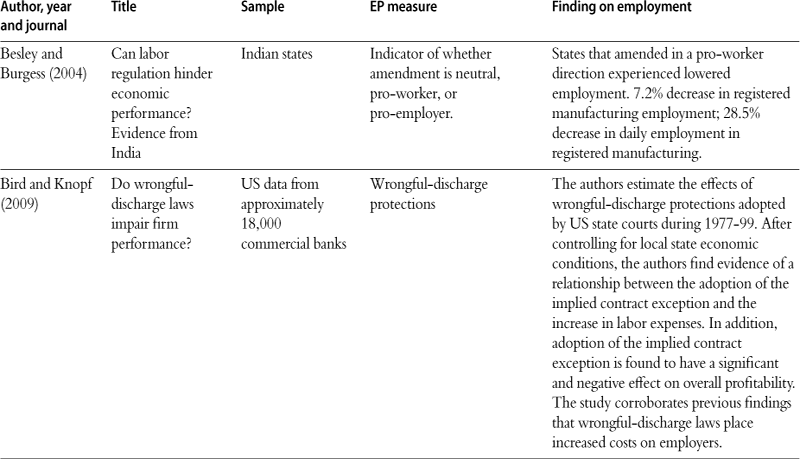

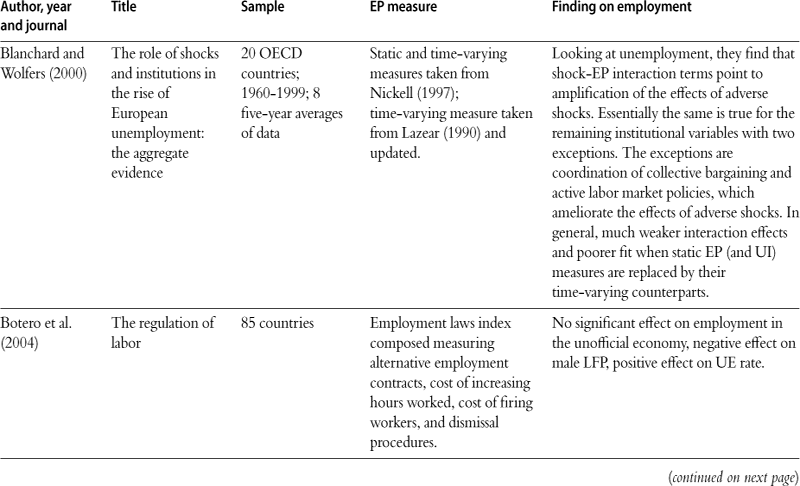

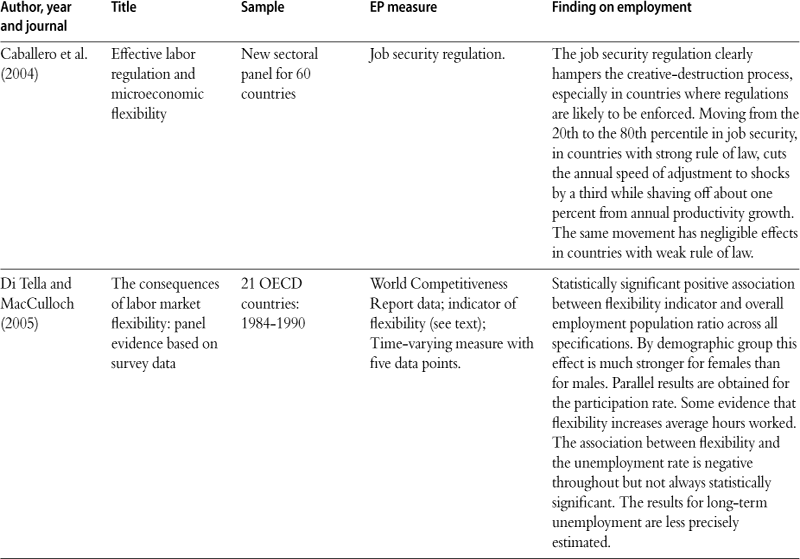

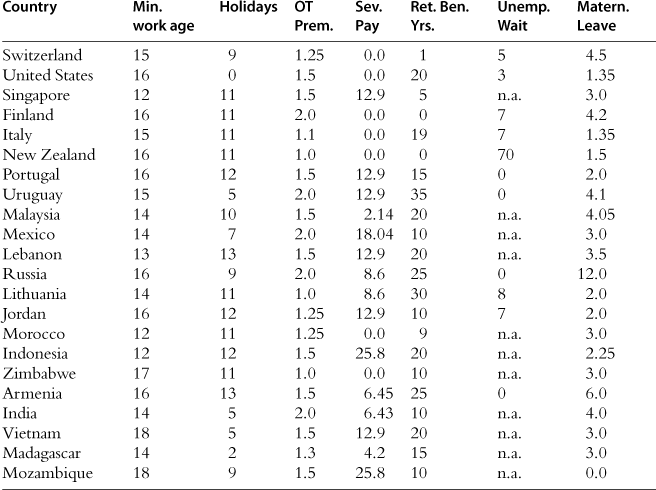

The purpose of this section is not to provide a comprehensive review of employment law. Rather, the goal is to provide a sense of how employment law has developed so that one might better understand its impact on the employment relationship.7 In the United States, employment law is primarily the domain of the states. Section 4 reviews several empirical studies that have exploited the natural experiments resulting from variations in state laws to measure the impact of various laws on economic performance. Overlaying the state laws are a number of federal statutes affecting the employment relationship, including the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 (allowing workers to organize collective bargaining units), Fair Standards Act of 1938 (establishing minimum employment standards), Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1973 (ERISA) (ensuring that employee benefits meet national standards), Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 (OSHA) (establishing minimum health and safety standards in the workplace), and Family and Medical Leave Act (establishing protections for leave related to personal sickness or family emergencies). These laws are enumerated in Table 1.

While the primary concern of the present chapter is the United States, studies of employment law in other countries are also discussed. Blanpain (2003), for example, provides a comprehensive review of European law. As in the United States, European law is complicated by the fact that both individual countries and the European Parliament create rules that affect the employment relationship. More generally, all countries in the world have some system of employment laws, created and adapted to the circumstances of each jurisdiction.

One chapter cannot do justice to the dizzying complexity of the law across jurisdictions, even if attention were restricted to a narrow area such as employee-dismissal law. As the quote from Holmes (1881) illustrates, legal systems are complex systems that evolve over time to resolve the variegated disputes faced by parties of commercial transactions. To make sense of this complexity, I follow the lead of the law-and-economics movement as epitomized in the work of Richard Posner, who argues that the law, especially the common law, has evolved over time to address the needs of individuals trading in a market economy.8 Posner (2003) explicitly poses the rhetorical question: “How is it possible, the reader may ask, for the common law—an ancient body of legal doctrine, which has changed only incrementally in the last century—to make as much economic sense as it seems to?”9

The claim is not that the entire body of rules and norms governing economic activity can be viewed as the solution to the problem of efficiently organizing economic activity. Rather, the claim is that individual rules have evolved to solve particular problems that appeared repeatedly before the courts. From this perspective flow some observations that may help explain the theoretical and rhetorical gaps between legal rule making, economic models of the labor market, and economic policy making. The advantage of the economic approach is that it allows one to explore the empirical implications of a simplified representation of the law. The disadvantage, particularly for purposes of economic policy analysis, is that the simplifying assumptions may miss key characteristics of the law that are important in practice.

This gap between law and economics is particularly salient in laws protecting employees from discharge, wrongful or otherwise. In economics, employment protections are typically modeled as a form of turnover costs, leading to the view that such laws probably interfere with an economy’s efficient response to shocks. As a consequence, organizations such as the OECD (see OECD (1994)) have advocated reducing or abandoning employment protections. Recent work by Blanchard and Tirole (2008) addressing how France and other countries should design unemployment insurance and employment protection concludes that there is no role for the law beyond enforcing employment contracts.

Nonetheless, as a matter of law, there are no jurisdictions where courts enforce all privately agreed-upon contracts. Labor contracts with young children, for example, are almost universally prohibited. Generally speaking, there is a substantial gap between the law in practice and the law as represented in many economic models of employment. One reason for this gap is that legal practitioners rarely have any reason to use an explicitly economic approach to understand the form of a particular contract. Lawyers typically represent clients in cases after the fact; the question of why a legal rule exists is not important to them. The real issue is to predict how a judge will rule and then present the case so that their client will do as well as possible in what is essentially a negative-sum game between the plaintiff and defendant. In this game, the details of the law are crucial, but the reasons why they have a particular form are not usually relevant.10

In consequence, the concerns of the legal scholar are quite different from those of the economist, which in turn creates a gap between the law as it exists and the law as modeled in economics.11 The goal of the next two sections is to narrow that gap ever so slightly, at least in the context of employment regulation. The next subsection discusses the generic structure of the law. Even though legal rules vary greatly from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, the notion of law and how it works has some universal features. More specifically, Section 2.1 examines three well-known employment-law cases in the United States and the United Kingdom. These cases illustrate the complex problem faced by a judge in an employment dispute. Moreover, as these cases demonstrate, the courts are not passive agents; they play an active role in resource allocation. Consistent with the “Posnerian” perspective, the decisions in some cases can be viewed as enhancing economic performance.

2.1 What is law?

The notion of a legal rule dates back at least as far as 2000 BC, with the Babylonians following Hammurabi’s code and the Mesopotamians following the code of Urukagina. While some of these ancient edicts imply curious beliefs about causality,12 it is clear that the purpose of many of these rules is to modify or constrain human behavior. For as long as law has existed, its purpose has been to facilitate the efficient functioning of civil society.

The aforementioned codes even had room for what we would now call labor law. Hammurabi’s code includes, for example:

• Minimum wage rules: “If any one hire a day laborer, he shall pay him from the New Year until the fifth month (April to August, when days are long and the work hard) six gerahs in money per day; from the sixth month to the end of the year he shall give him five gerahs per day”.

• Liability rule: “If a herdsman, to whom cattle or sheep have been entrusted for watching over, and who has received his wages as agreed upon, and is satisfied, diminish the number of the cattle or sheep, or make the increase by birth less, he shall make good the increase or profit that was lost in the terms of settlement”.

These are remarkable examples of how legal rules are created to regulate the employment relationship. That minimum wage rules persist to this day suggests that there are robust reasons for the existence of such rules. Recognizing this possibility, the law-and-economics approach seeks to explain the rules as solutions to well-defined market imperfections. Ostrom (2000), for example, has shown that many societies have developed efficient systems of rules and adjudication for regulating the use of common-pool resources, thereby avoiding the tragedy of the commons (Hardin, 1968). Ostrom observes that all successful commons-governance regimes consist of a set of rules that have the following features:

1. The rules are commonly known;

2. There are penalties for breaking rules that increase in intensity with the severity and frequency of violation;

3. There is an organization or an individual who is responsible for imposing penalties when informed; and

4. There is a process of adjudication when there are disagreements regarding whether an offense has occurred and what penalty should be imposed.

All organizations, including firms and families, have rule systems with these features. The economic analysis of such rule systems typically entails asking what set of rules would achieve an efficient allocation.13 In the common-pool-resource problem, for example, one seeks a set of rules ensuring that each person with access does not overuse the resource. Organizational economics tries to determine which systems of rules and compensation in firms or public entities ensure that agents reveal useful information and choose efficient levels of effort.

What distinguishes the law’s rule system from a family’s or organization’s is not the existence of binding rules, but the sources of enforcement and adjudication. When we speak of a legal system, we mean the set of rules and associated penalties that are enforced by the state.14 As discussed above, however, the jurisdiction associated with a dispute is often poorly defined. Even when the jurisdiction is well-defined, disputes can often be decided by multiple judicial bodies (including private mediation and arbitration). Many countries, such as Italy and the United Kingdom, maintain a separate system of courts for ruling on employment disputes. In the United States, disputes regarding a collective-bargaining agreement may be brought before the National Labor Relations Board, employment disputes before a state court, and Title VII discrimination suits before a federal court.

To illustrate what we mean by a legal system (and employment law in particular), let us consider the proverbial worker-firm relationship. In the standard neoclassical model of employment, the worker agrees to supply L hours of labor for a wage w. This can be viewed as a supply contract where the hours are, say, consulting time. In that case, the relationship would be governed by contract law. The worker must supply L hours, and the employer must pay w L dollars.

Should the worker supply less than L hours, the worker has breached the contract. Suppose that the firm has paid P0 in advance, a common practice if the worker is, for example, a lawyer. Some sort of binding agreement is needed; otherwise, the worker would simply take the P0 and try to find employment elsewhere. The question, then, is: What incentives does the worker have not to breach the agreement?

One possibility is the use of an informal enforcement mechanism. This would include firms’ telling each other that the individual has breached, and hence should not be dealt with.15 Another alternative is to use physical violence against the individual, a common technique in the illegal drug trade and other black markets.16 While both enforcement systems are still widely used, societies have evolved more legalistic systems of adjudication for the simple reason that parties sometimes fail to perform even if they act in good faith. Enforcement systems that trigger punishment regardless of the reason for breach, such as violence among drug dealers, are simply not always efficient.17

In contrast, if the contract is viewed as a legally binding agreement, then the breach of contract by the worker gives the firm the right to seek damages in court. If the firm prevails, the court can order the worker to pay damages to the firm; if the worker refuses to pay, the court can still enforce the decision by ordering the seizure of the worker’s assets.

The fact that contract breach leads to the right to file suit—as opposed to an automatic penalty—is a feature that distinguishes legal enforcement from other forms of rule systems, such as rewards within a firm. In the economics literature, it is common to view any agreement between parties that links future rewards to actions as a “contract”. Jensen and Meckling (1976), for example, famously proposed that one should conceptualize a firm as a “nexus of contracts”. If all contracts are enforceable at negligible cost, a reward system that promotes an employee for good performance and an agreement with an outside supplier to pay a bonus for sufficient quality are assumed to be equally enforceable. If employment contracts are enforceable at no cost, subject only to information constraints, then explaining the contract form requires only that one carefully specify the environment and then use principal-agent theory to work out the optimal contract.

The difficulty, as Williamson (1991) observes, is that the law uses forbearance for transactions within a firm. Even if a firm promises a promotion, that does not confer a right upon the worker to sue the firm should the promotion not be offered. All dispute resolutions of this sort occur strictly within the firm, with no appeal to an outside legal authority available. A full discussion of the role of courts in such disputes must wait until the next subsection, but for now the relevant point is that for any contract between two legal persons (in our example, firm and consultant), both parties always have the right to seek damages in court should there be a breach of contract.18

That the decision to sue is discretionary implies that the same rule may have different effects depending on the characteristics of the parties of the contract. The characteristics of the parties might even be the most important factor in whether a lawsuit is filed. For example, suppose that a company has illegal discriminatory hiring practices. If the market is thick, with plenty of employment alternatives, potential employees may not find it worthwhile to bring suit against the company. In a less friendly employment market, if an individual believes he has been the victim of illegal discrimination and cannot find another job, he may bring suit. This point is illustrative of the fact that we will always find differences between a legal rule on paper and the same rule in practice.19

A second source of uncertainty is how the court will decide a case. In the case of the breaching consultant, the court has to make two decisions, each of which is prone to statistical error: (1) deciding whether a breach has occurred, and (2) if so, the damages to be paid. For damages, the general rule is that courts order expectations damages— namely, the losses associated with the worker’s breach. An example of a formula that the court might use is:

![]()

Here w1 is the wage for the replacement worker. The worker has to pay the costs associated with finding a replacement worker rather than the value of the work done, due to contract law’s requirement that injured parties make every effort to mitigate losses arising from breach. The mitigation rule is mandatory, meaning that parties cannot contract around it. Employment law has many other mandatory rules; slavery is prohibited, for example, as is discrimination on the basis of race, age, or sex.

Expectation is not the only way to calculate damages from contract breach. In a famous paper on contract damages, Fuller and Perdue (1936) identified restitution and reliance as other possible measures of damages.20 Restitution damages, for one, are intended to put the firm into the same financial position—as if the contract had never been signed. In our consultant example, restitution damages would only require the worker to repay P0. Matters are less clear if P0 is paid to the worker so that he can buy passage to the job site and secure accommodation. Suppose upon arriving, the worker is injured and cannot perform his duties; the firm sues for breach. If the contract does not specify what happens in this contingency, a court may be asked to fill in the gaps in the agreement. Some other issues that might not be described in the contract (and which the court must adjudicate) include whether the injured worker may be fired or whether he must take out a loan to repay P0.

Alternatively, the firm, in the expectation of being able to rely upon performance, may have paid for passage and accommodation. In that case, if the worker does not perform, then she may be asked to compensate the firm for these reliance expenditures.

Finally, the contract could have provided that a non-performing worker pay a fine P0. In this case, non-performance would not be a breach of contract, and a breach would occur only if the worker failed to pay back P0. Notice that in this case, the damages would simply be P0, even under the expectation-damages rule. This example illustrates that for the same exchange relationship there is no unique notion of contract breach. Rather, the contract defines what constitutes breach, and then the courts must decide whether or not to enforce the terms set out in the agreement.21

Defining the conditions for breach is not a clear-cut exercise. For example, the contract could have specified liquidated damages in the amount P0. In this case, breach would occur for non-performance, but then the contract would direct the court to set damages at P0. This contract seems to be equivalent to the previous one (indeed, most economic theories of contract would see them as equivalent), but there is an important distinction. In the previous case, if the worker pays P0, no breach has occurred, and the firm has no right to bring suit against the worker. In the liquidated-damages case, even if the worker offers to pay P0, the firm still has a right to sue the worker because technically a breach has still occurred. Admittedly, the firm would face an uphill battle in court if the worker had offered to pay—and normally would have no reason not to accept the offer as part of a settlement agreement—but the right exists nonetheless. The firm might believe, for example, that the worker abused the liquidated-damages clause, accepting the consulting job only as a contingency in case another opportunity did not work out. If the firm’s belief is true, the worker has arguably violated the requirement of good faith and fair dealing—another mandatory rule in the common law of contracts. Arguing that the liquidated-damages clause no longer applies, the firm might ask for expectation damages larger than P0.

Conversely, assume that the firm sets liquidated damages at three times P0. Breach occurs, and the worker declares these damages to be unconscionably high. The worker may have a valid claim under contract law’s prohibition against penalty clauses. This doctrine—another mandatory rule—provides that liquidated damages far exceeding the losses to the injured party will not be enforced by courts.

The prohibition on penalty clauses, along with the other examples of mandatory rules discussed above, illustrate that the law allows for a significant degree of judicial intervention into private contracts. Among other things, a court can fill in missing terms and refuse to enforce unreasonable terms. The decision whether to intervene is often at the court’s discretion, but courts usually turn to the Uniform Commercial Code and other statutes, as well as previous court decisions, to justify these interventions. Thus the legal system is an adjudication process that modifies contracts in the face of a breach as a function of past experience and practice.

The extent to which courts should intervene into freely entered agreements has proven to be controversial. Early scholars, such as MacNeil (1974), proposed that courts rely on many sources of information, including industry custom and the history of the relationship between the plaintiff and the defendant, when making a decision. If parties have a longstanding relationship, Macneil argued, contract terms should be enforced within the context of the relationship. Macneil and many others believed that this sort of context-sensitive adjudication could help repair the parties’ relationship and facilitate the continuation of mutually beneficial exchange. Most economic theories of contract, in contrast, work from the assumption that parties have well-defined interests and can draft agreements efficiently, implying that contracts should be enforced as written. This presumption has led to a law-and-economics scholarship that mostly argues for the curtailment of judicial discretion, and for a more systematic dependence upon basic economic reasoning when ruling on a case (see Goetz and Scott (1980) and more recently Schwartz and Scott (2003)).

Regardless of one’s theoretical commitments, it remains the case that the law does not simply enforce a set of well-defined rules. The law does include a set of rules, but along with a system of adjudication that results in a context-sensitive application of these rules to individual cases. This context sensitivity includes, among other things, consideration for the idiosyncratic features of the parties. The basic principles of contract law apply to all agreements between two parties, but more specialized bodies of law have evolved to regulate specific classes of contracts. The insurance industry is regulated by a specialized area of contract rules (see for example Baker (2003)) as is employment law. It is to this latter body of law that we now turn.

2.2 Employment law

Employment law evolved from contract law and master-servant law to deal with the unique problems characterizing the modern employment relationship. The first task is to determine the difference between (1) a firm’s relationship with an outside contractor selling services, and (2) its relationship with an employee. The difference not only affects the area of law that regulates the relationship, but it also affects the relevant tax law. In the United States, the Internal Revenue Service will find that an employment relationships exists when “the person for whom services are performed has the right to control and direct the individual who performs the services, not only as to the result to be accomplished by the work but also as to the details and means by which that result is accomplished”.22

As this tax regulation exemplifies, the obligation of the employee is to follow his employer’s directions, not to produce a specific service with particular characteristics. Simon (1951)’s model nicely captures this distinction between sales and employment. In a sales contract, says Simon, the seller agrees to supply a particular good or service x from the set of all possible goods and services X, and in exchange the buyer agrees to pay a sum P. An employment relationship, in contrast, is characterized by a subset of all possible goods and services, A ⊂ X, that represents the set of duties that the employer might ask the employee to carry out. A might include the service x defined in the aforementioned sales contract, but that single task would normally be just one component in a broad complex of obligations defining an employment relationship. In exchange for a promise to carry out these duties, the employer agrees to pay a wage w.

Simon’s simple model highlights an essential feature of the employment relationship, namely, the admissible scope of a person’s job as represented by the set A. The admissible set of tasks S ⊂ X −that is, the set of acts that an employer is allowed by law to command—has been subject to a plethora of regulation and litigation. For example, is it conscionable for a firm to require 50 hours a week? Can a manager ask her assistant to commit crimes?

An employment relationship often begins with little formal agreement about the tasks the employee will be asked to carry out. The longer the potential duration of the employment, the more incomplete the initial employment agreement. Given the informal nature of such agreements, when disputes do arise the courts will have little to rely upon when constructing the obligations of each party. With poorly defined obligations, determining whether a breach occurred presents a difficult task, as does choosing an appropriate remedy.

The combination of extreme contract incompleteness and daunting litigation costs have convinced many legal scholars that the appropriate default rule is at-will employment. The courts have converged to this default rule partly because they now view employment law as an extension of contract law. That view diverges significantly from the early case law on employment disputes, which was mostly governed by “master-servant law”.23 That old body of law consisted of a set of legal default rules developed in England and the United States to deal with cases involving domestic servants. In the master-servant relationship, the customary period of employment lasted one year; courts held that neither party should sever the relationship before then.

In a widely cited work, Wood (1877) argued for replacing this law with the rule of at-will employment, where both parties can sever the relationship whenever they wish and face no liability beyond the requirement that the employer pay her employee the agreed-upon wage for work already completed. Wood’s argument was a pragmatic one, based on the bad experiences of many employers and employees with the inflexibility of master-servant law. As detailed in Feinman (1978), the new rule was quickly adopted by the New York courts and remains the default rule today. In California, the legislature adopted what is now Section 2922 of the California Labor code, which provides that “employment, having no specified term, may be terminated at the will of either party on notice to the other”.

The at-will-employment rule figures prominently in most economic models of the labor market. As these models have it, workers and firms enter into relationships that are preferred to the alternatives in the marketplace. Should a firm mistreat a worker, or have high standards for performance or number of hours worked, the firm will have to pay relatively high wages or else the worker will leave. Similarly, if a worker demands a higher wage or better working conditions, the firm is free to search for another worker who will abide by the current arrangements. In equilibrium, all firms and workers are satisfied with their lot relative to the alternatives.

The hypothesis of a perfectly competitive market can explain many broad features of wages and employment over time, but it cannot explain the emergence of the at-will-employment rule. This is an example of the model’s inability to explain the emergence of laws that seem to constitute reasonable responses to real economic issues. That failure indicates flaws in popular economic models—but not in economic reasoning generally. Consider the case of child labor. As societies have become more wealthy, they have gradually imposed stricter legal constraints on the minimum age and maximum hours for minors in the workplace. By the perfectly-competitive-market hypothesis, these restrictions would be unjustified because only those families for which child labor is efficient would put their children to work rather than in school. On the other hand, a more realistic economic inquiry recognizes the market imperfection imposed by liquidity constraints: children (and parents) cannot borrow against future income arising from education, so many families send their children to work for a short-term gain in income rather than invest in a long-term gain from education. Investing in education results in superior overall welfare, so the choice to put children to work is inefficient. Laws that regulate child labor, like the Fair Labor Standards Act, are justified because, by increasing the cost of child labor, they motivate families to substitute education for labor. By increasing investments in education, these laws increase social welfare.

The analysis in the previous paragraph indicates the potential insight to be gained from an evolutionary perspective when investigating the law and economics of employment law. Applying this perspective to our law’s historical origins, we observe that employment law adapts to the changing macroeconomic environment. One of the earliest labor statutes on record, the Ordinance of Labourers, addressed the problems of unharvested crops, rising wages, and poaching of workers faced by English landowners at the height of the Black Death. Similarly, in 1630, the Massachusetts General Court placed a wage cap of 2 shillings a day on skilled craftsmen, who were at that time taking advantage of limited supply. More recently, the Fair Labor Standards Act became law in the midst of the Great Depression, when workers lacked market power to ensure good working conditions. Mandatory overtime pay, meanwhile, incentivized firms to hire more workers at fewer hours each, thereby serving as an income- and risk-sharing function.

These legal adaptations to changes in the labor-market environment can all be conceived as forms of insurance, whether against the waste of unharvested crops, gouging by craftsmen, or unemployment. In the next subsection, we discuss recent work based on the hypothesis that workers are risk-averse, which might help explain some of the features of these laws. Certainly, both minimum-wage laws and unemployment insurance can be viewed as forms of imperfect insurance.24

Once the issue of risk is put aside, the law-and-economics movement has tended to take the view that employment at will is the optimal default rule (see, e.g., Epstein (1984)). Within economics, a tradition including Friedman (1962) and Alchian and Demsetz (1972) has viewed labor services from the perspective of the buyer-seller contract—with no remedies for contract breach. Specifically, Friedman argued that a competitive market with free entry and exit is the most efficient market form, even when contracts cannot clearly specify quality. In his vision of the world, workers and firms trade freely within the context of the sales contract (quality x in exchange for price p); should performance be inadequate, the worker would gain a poor reputation and thereafter be excluded from the market.

There are two difficulties with this argument. The first, as MacLeod (2007a) discusses, is that the literature on relational contracts shows that reputational concerns are neither necessary nor sufficient to ensure efficient exchange. Second, the common law has developed many doctrines that limit the freedom of contract in the context of the simple buyer-seller model. Posner (2003) suggests that these developments tend to enhance contract performance. Chakravarty and MacLeod (2009) present evidence that this is indeed the case for a large class of contracts that are common in the construction industry.

As the Simon model highlights, the employment relationship is different because a performance obligation is created ex post. If the worker accepts a contract with scope A ⊂ X, then the performance obligation is created when the employer asks the employee to carry out x* ∈ A. If the relationship were governed by standard contract law, then if the employee chooses xb ≠ x* the employer-cum-buyer could sue for damages B(x*) – B(xb), where B(x) is the benefit to the employer of action x. Under employment at will the general rule would be that the employer has no right to sue, but she can freely dismiss the employee, even if performance is satisfactory.

Correspondingly, the employee has the right to leave whenever he wishes. For example, if the employer asks the employee to carry out an action outside the scope of his duties, then under at-will employment the employee has the right to refuse to carry out the task and find another job. In contrast, in the case of a construction contract, if the buyer were to ask for a modification to the building plan, then under US law the contractor would have an obligation to carry out the modification, but he would also have the right to sue for the additional cost of the change if the buyer/builder does not adequately compensate him for the changes.

The defining feature of at-will employment is that in each period parties are free to renegotiate the contract, with the outside options defined by each parties’ market opportunities. Consistent with the Coase theorem, we should expect at-will employment to give rise to arrangements that are ex post efficient. This observation has led some legal scholars (e.g., Epstein (1984)) to suggest that exceptions to employment at will are inefficient. Yet today in the United States, as in most other jurisdictions worldwide, the law of wrongful discharge is alive and well. Indeed, there are clear exceptions to the rule of employment at will. In the next section, we discuss three of the most important exceptions figuring in recent empirical work on employment law.

2.3 Exceptions to employment at will

This section discusses three exceptions to employment at will that have found broad support in US courts. These exceptions are judge-made laws, created in response to difficult cases; hence, they are good examples of how the common law evolves in response to the disputes that arise in practice. The three exceptions we consider are (1) the public policy exception, protecting from employer retaliation those workers that act in a way consistent with accepted state policy, (2) the implied contract exception, protecting workers who can show that the implicit contract with the employer entails just-cause dismissal, and (3) the good-faith exception, requiring employers and employers to behave in ways consistent with fair dealing.

US courts rarely order specific performance—that is, the losing employer typically still has the right to discharge the employee—and hence the issue is usually one of damages: How much should she have to pay for this right? In other jurisdictions, however, reinstatement is sometimes considered an acceptable remedy. One of the few US cases in which specific performance was granted in an employment dispute was Silva v. University of New Hampshire.25

The question of damage awards is not straightforward, but economics can assist in organizing our thinking. If markets are perfectly competitive—and a worker’s compensation is equal to his best market alternative—dismissal does not entail any harm. However, as Mincer (1962) has shown, the second assumption can break down when the worker’s training costs were significant. If the worker paid for some of the training costs, he will be compensated for them through increased future compensation, and therefore his income may be in excess of the best market alternatives. More often, dismissal entails a costly job search and possibly relocation. When an employee has been wrongfully discharged, the court will award damages that reflect these costs.

An additional complication is whether the wrongful-discharge action comes under tort or contract law. The first exception to the at-will employment rule, a claim for wrongful discharge as violation of public policy, is considered a tort claim.26 A tort claim, put briefly, is distinguished from contract disputes by there being no requirement for a prior contractual relationship. Standard examples include traffic accidents and medical malpractice. The practical implication of this distinction is that tort law allows for the recovery of both consequential damages and punitive damages, which may far exceed the direct economic harm suffered by the discharged employee. In contract law, consequential damages and punitive damages are in general not recoverable.

2.3.1 Public policy exception

Under the public-policy exception, an employee may sue for wrongful discharge if he is dismissed for conduct that is protected by law. Miles (2000) summarizes the four types of terminations that fit under this class of exception.27 They are (1) “an employee’s refusal to commit an illegal act, such as perjury or price-fixing”; (2) “an employee’s missing work to perform a legal duty, such as jury duty or military service”; (3) “an employee’s exercise of a legal right, such as filing a workman’s compensation claim”; and (4) “an employee’s ‘blowing the whistle,’ or disclosing wrongdoing by the employer or fellow employees”.

A well-known example of the first type of public-policy exception is the 1980 case Tameny v. Atlantic Richfield Co.28 Plaintiff Tameny, the dismissed employee, claimed that his discharge resulted from a refusal to participate in the company’s unlawful price-fixing scheme. Defendant Atlantic Richfield argued that since there was no employment contract, Tameny’s employment was at-will and could be terminated at any time. The California Supreme Court ruled for Tameny, holding that an employer cannot discharge an employee for refusing to perform an illegal act. The court further held that the employee can recover under tort law, thereby allowing for potentially higher damages. On this last point, the moral distinction between tort and contract—specifically, that a breach is blameless, but a tort is wrongful—is relevant. Atlantic Richfield did not just breach a contract, it retaliated against an employee for refusing to do its criminal dirty work. Consistent with our moral intuitions, the court considered the company’s conduct to be morally wrongful—not just business as usual—and therefore established a legal mechanism for increased punishment of such conduct.

Economic models of employment mostly ignore illegal activity on the part of employees, yet Tameny and other cases involving the public-policy exception clearly demonstrate that some employers do ask employees to commit crimes. The economic implications of this rule are difficult to tease out. In Tameny, at least, the employee was asked to engage in anti-competitive activity, so in this case the public-policy exception probably enhanced economic efficiency. But economic evaluations of public-policy cases are generally more difficult. If the illegal activity entails consumer goods, such as drugs or gambling, then the public-policy exception likely decreases output, albeit in a direction that arguably enhances social welfare. The prohibition against discharge for military service, meanwhile, reduces economic efficiency because it prevents the employer from finding a more productive replacement. As with the illegal-consumer-goods exception, the military-service exception to at-will employment arguably serves other social-welfare goals.

2.3.2 Implied contract exception

When a worker can verify that a permanent employment relationship is promised by his employer, such employment can no longer be regarded as at-will and can be terminated only under just cause.29 Under reigning court precedent in some states, if a personnel manual given to employees specifies that termination is only with cause, a binding contract exists. Woolley v. Hoffmann-La Roch was the first opinion to hold that employee handbooks can be part of a legally binding employment contract.30

The facts of Woolley are as follows. Plaintiff Richard Woolley was hired by defendant Hoffmann-La Roche, Inc. in 1969 as section head in one of defendant’s engineering departments. The parties did not sign a written employment contract, but the plaintiff received a personnel manual which read, in part, that “[i]t is the policy of Hoffmann-La Roche to retain to the extent consistent with company requirements, the services of all employees who perform their duties efficiently and effectively”. In 1978, after Woolley’s submission of a report on piping problems at one of defendant’s buildings, defendant requested that he resign. Plaintiff refused, and he was fired.

The trial court judge held for the defendant on summary judgment. On Woolley’s appeal, the New Jersey Supreme Court reversed and remanded the case for trial, holding that an employee’s handbook could be evidence of a binding contract. The court couched its ruling in notions of fairness:

All that this opinion requires of an employer Is that It be fair. It would be unfair to allow an employer to distribute a policy manual that makes the workforce believe that certain promises have been made and then to allow the employer to renege on those promises. What is sought here is basic honesty: if the employer, for whatever reason, does not want the manual to be capable of being construed by the court as a binding contract, there are simple ways to attain that goal. All that need be done is the inclusion in a very prominent position of an appropriate statement that there is no promise of any kind by the employer contained in the manual...

In this case, as in many others, one party is not completely truthful with the other party. This possibility is ignored by most economic models of contract. Economists typically assume that both parties do what they say they will do, and if they do not, any malfeasance is anticipated by the other party. The Woolley opinion can be seen as requiring employers to comply with previous agreements not to engage in malfeasance. The judgment does not prohibit dismissal without cause; it simply requires that employers honor promises not to dismiss without cause.

Employee handbooks are not the only example of an implied contract. For example, Pugh v. See’s Candies held that a long employment with regular promotion can establish a long-term contract.31 In this case, the plaintiff-worker Pugh reported to company higher-ups that his current supervisor was a convicted embezzler, for which the supervisor subsequently fired him. Pugh filed suit, but the trial court dismissed the case at summary judgment. On appeal from the dismissal, the appellate court agreed that Pugh’s reporting his supervisor’s past conviction was not “whistle-blowing” under the public policy exception, but the long duration of Pugh’s good service was sufficient to establish an implied contract. The court therefore reversed and remanded the case for trial.32

This example illustrates a concrete case in which an employee is dismissed not because of an objective failing (otherwise one could provide cause for dismissal) but because, essentially, he did not get along with his new supervisor. If the contract were at-will, then dismissal would be immediate. This rule prohibits the dismissal of long-term employees who may not fit in, or, if delinquent in their performance, the employers are unable to provide sufficient evidence of this poor performance.

2.3.3 Good faith exception

The requirement of good faith and fair dealing is a mandatory rule in contract law, and consequently in employment law. The employment cases involving this exception typically turn on the use of at-will employment by the employer to deprive the employee of compensation. In Mitford v. Lasala,33 the discharged employee, who was a party of a profit-sharing agreement with the defendant, was fired to ensure that he would not share profits. The court held that “good faith and fair dealing... would prohibit firing [an employee] for the purpose of preventing him from sharing in future profits”.

Currently, courts typically find a rather narrow application of this rule to the timing of dismissal and payment of compensation, rather than to other forms of bad behavior by employers.34 Typical examples of wrongful terminations that fit under this class are: (1) a salesman being fired right before his commissions should be paid to him, and (2) an employee being dismissed in order to avoid paying retirement benefits.

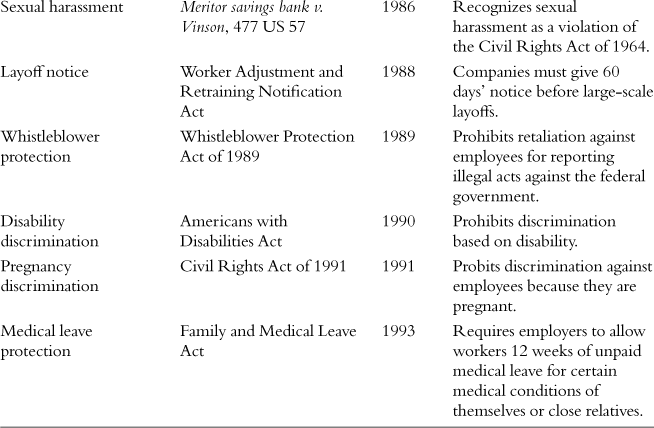

As we can see from Fig. 1 there are many fewer states adopting this law than in the case of the implied contract rule. Given the more narrow applicability of the rule, this may simply reflect the fact that courts in these states have adhered more closely to the common-law principle of at-will employment, and hence there was a need for statutory intervention to deal with cases where employers avoid paying compensation by a preemptive dismissal. If so, then we might expect this rule to have a substantial impact.

This impact is not due to the effect upon firing costs, but rather because it corrects poorly drafted contracts. In the case of Mitford v. Lasala, the contract was quite clear, and it implied that the firm had no obligation to pay the bonus. Most employees would expect to be paid in such a case, but at the time of writing the agreement they simply would not expect the deception to occur. In such cases, the courts can enhance productive efficiency by essentially completing an incomplete contract.

Consider now the case of Fortune v. National Cash Register Co.35 Plaintiff Orville E. Fortune, a former salesman of National Cash Register Company (NCR), brought a suit to recover certain commissions allegedly due from a sale of cash registers to First National Stores. Inc. Fortune had been employed by NCR under a written contract that provided for at-will mutual terminable with notice. The contract also specified that Fortune would receive an annual bonus computed as a percentage of sales that he performed or supervised. In November 1968, Fortune was involved in a supervisory capacity in a sale of 2008 cash registers to First National, for which the bonus credit was recorded as $92,079.99. The next month, Fortune was given notice of termination. NCR ended up keeping Fortune on staff in a demoted capacity, and paid him three-fourths of the First National bonus during the summer of 1969. Fortune requested the other 25% of the bonus, but his manager told him “to forget about it”. Fortune was finally asked to retire in June 1970, and then fired upon his refusal.

At trial, the jury was asked to render two special verdicts: “1. Did the Defendant act in bad faith ... when it decided to terminate the Plaintiff’s contract as a salesman by letter dated December 2, 1968, delivered on January 6, 1969? 2. Did the Defendant act in bad faith ... when the Defendant let the Plaintiff go on June 5, 1970?” The jury answered both questions in the affirmative, and the judge ordered damages of $45,649.92. The state supreme court affirmed the judgment.

What is interesting about this case is that NCR did not breach the written terms of the agreement, but the court nevertheless allowed a jury to find that they had acted in bad faith in depriving Fortune of bonuses from the transactions he helped procure. Fortune can be seen as an efficient outcome in that it reduces employee uncertainty about whether they will be rewarded for their efforts and thereby incentivizes optimal investment in the employment relationship.

2.4 Discussion

The economic model of contract tends to view legal rules as constraints upon individual decision-making, either in terms of increasing transaction costs or imposing constraints upon the wages, hours, and other conditions of employment. In practice, the law is a complex adjudication system that is difficult to describe with an elegant model. Some of the distinctive features of a legal system that are not captured in the economic model of the employment contract include:

1. Contract terms are not self-enforcing. Enforcement is a privately motivated activity that occurs when a plaintiff brings a case before a court. Even rules that have bureaus dedicated to their enforcement—such as the minimum wage and overtime requirements—rely on information provided by private parties—as well as the volition of agency officials. This demonstrates that enforcement is heterogeneous and a function of employer, employee, and regulator characteristics.

2. When a case is brought to a court, parties cannot rely upon the courts to enforce the agreement as written. Excessive penalties for non-performance are not enforced, for example. Although employment at will is the default rule in the United States, there are several exceptions.

3. Judges do not restrict themselves to contract terms, explicit or otherwise, as relevant legal factors. Courts may collect a large body of evidence regarding the communications and actions of both parties before reaching a decision. Thus, information regarding events not mentioned in the employment contract may nevertheless play a role in adjudicating the dispute.

The fact that courts may overrule contract terms is well-recognized in the legal literature. One of the central issues of this literature is the question of whether or not there is anything we can reasonably call “the law” that allows one to consistently anticipate how courts will rule on a given dispute. There is a related debate regarding how best to think about judicial behavior.36

Within economics, there is a small but growing literature that explores the role of the law in ensuring performance. Johnson et al. (2002) find that even if enforcement is imperfect, the existence of courts can help entrepreneurs enter into new supply contracts. Djankov et al. (2003) construct a database consisting of how costly it is to evict a tenant and collect on a bounced check across a large sample of countries, finding that the cost of collection in civil-law countries is significantly higher than in common-law countries. This result is consistent with subsequent work reported in Djankov et al. (2008) for the problem of debt collection. See La Porta et al. (2008) for a more comprehensive discussion of this literature.

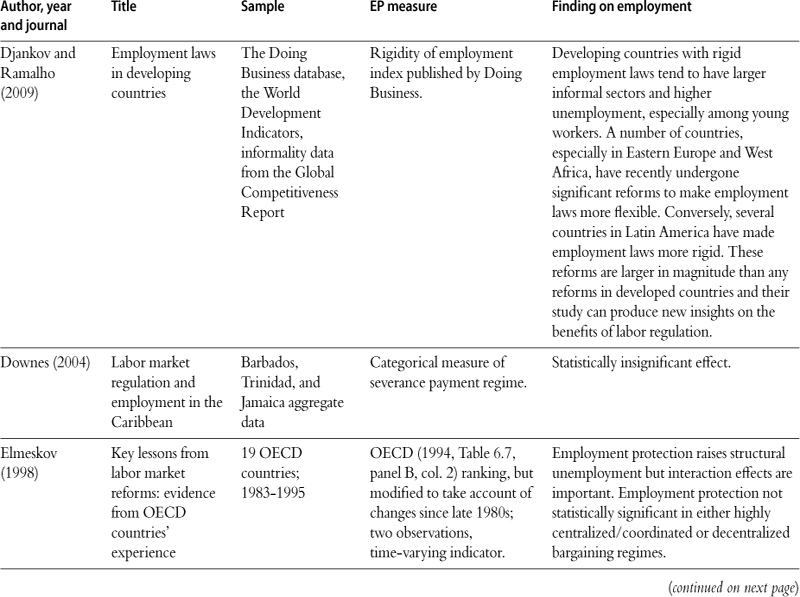

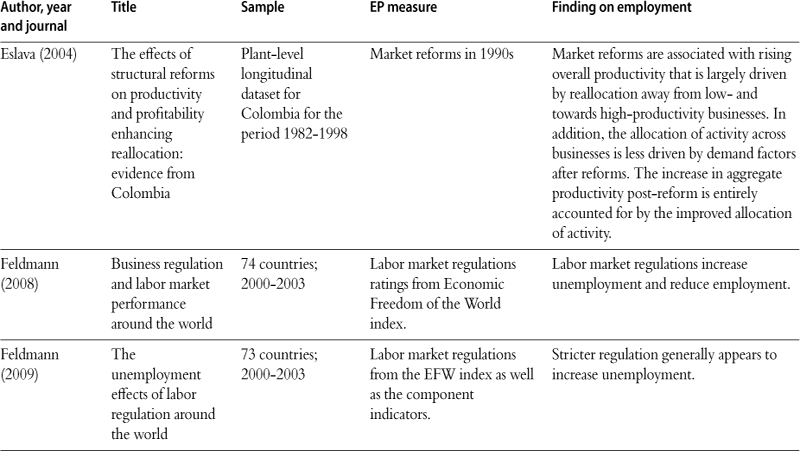

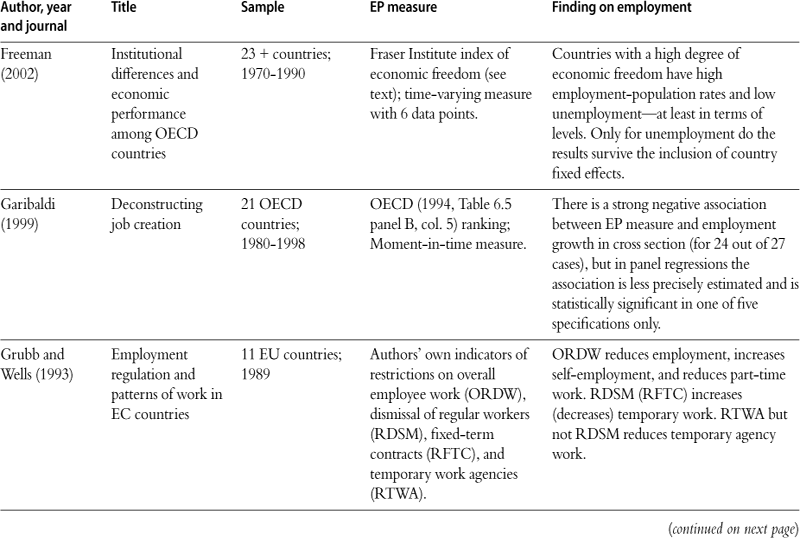

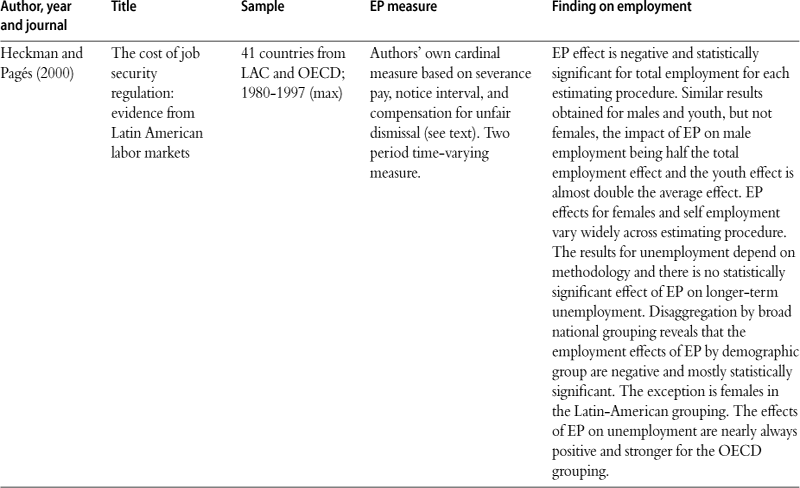

For the most part, this work focuses on the costs of the legal system and assumes that variations in these costs across jurisdictions affect economic performance. Botero et al. (2004), and more recently Djankov and Ramalho (2009), explore the extent to which employment law and regulation affect labor market performance. This work uses crosscountry variation in measures of employment-law flexibility to identify the effects of the law upon labor-market performance. These papers suggest that the historical origin of the country’s legal regime—whether common-law or civil-law—is often the decisive factor in the evolution of the country’s employment rules. However, these papers do not explain this observation. One possible interpretation, perhaps in need of further research, is that laws, like organisms, are adapted not just to the environment but to other laws. The various laws in a legal system—of which employment law is a small part— persist at a steady-state equilibrium unless an overwhelming shock—whether political or economic—suffices to move enough laws to another equilibrium to pull the rest of the legal regime along with them. The rarity of such events—Russia’s transition to capitalism is a plausible example—might explain the durable influence of common-law and civil-law institutions on employment laws.

Regardless of this latter conjecture, what is clear from the analysis above is that the law is adaptive, yet existing work does not adequately explain why there is variation in the law. The plausible view taken here is that the law evolves in response to cases brought before the courts. New types of disputes breed new types of law. To understand why these cases arise, we need to understand what exactly is the role of the law in an employment contract. In the next section, we review the literature on the economics of the employment relationship, placing legal rules in the context of the full relationship.

3 The economics of the employment relationship

Economic theories of employment begin with a model of human behavior and choice. The standard assumption in economics models of employment is that the worker is a risk-averse individual who wishes to maximize expected utility adjusted for the utility from doing specific tasks and the work environment.37 One of the lessons of contract theory is that the optimal contract is often a complex function of the technology of production, the characteristics of the prospective employer and employee, and the information available. In order to highlight the empirical implications of the theory, we begin with a discussion of causality. We then discuss economic models of the employment relationship, highlighting their empirical implications.

3.1 Why do we need models?

The purpose of this section is to review the role that economic theory plays in understanding the significance of the law. As discussed in Section 2, even though economic concerns shape the development of the law, economic analysis as developed by the economics profession has played a relatively minor role in explicitly guiding court decisions.38 While there may be no explicit accounting of economic effects, it is safe to say that employment rules established by courts have measurable effects on the economy. Accordingly, the goal of the theory discussed here is to structure empirical tests of the impact of employment policy on economic performance.

The recent empirical work in labor economics has been greatly influenced by the potential-outcomes framework, as beautifully exposited by Holland (1986).39 I shall briefly review this approach when using economic theory to understand the effects of the law on labor-market performance. First, the framework provides guidance on how to best organize and represent data. Second, it provides guidance on how to estimate a causal effect. Holland emphasizes that it is impossible to establish a causal relationship without some additional hypotheses that themselves can rarely be tested; they must rely on a model of how the world works.

Formally, the model proceeds by supposing that we have a universe of units to be treated, denoted by u ∈ U. For the purposes of our discussion, let U denote all potential workers in the economy. In addition, we might also be interested in outcomes at a state or country level. In that case we let us ⊂ U be the subset of individuals living in state s ∈ S, where s could denote a US state among all states or one country among all countries.

This chapter’s main concern is labor-market performance, so we restrict our attention to the question of how policy might affect wages and employment. For individual u, let yE ∈ YE = {0, 1} be employment status (with 1 meaning employed), and let her wage per period be given by yw ∈ YW = [0, ∞). Suppose that these outcomes will be observed in the next period (t). Employment and wages are likely to be affected by employment policies in the next period, denoted by lt.

Rubin’s model was developed in the context of a medical treatment where one asks if a particular drug has an effect. This question is typically answered by randomly dividing a group of individuals into a treatment and a control group. The causal effect of the drug is measured by comparing the outcomes in the two groups. The problem is that this procedure does not identify the effect of the treatment on a particular individual. In some illnesses, individuals become well in the absence of treatment. For others, the illness may be fatal regardless of the treatment. By chance, it is possible that all the former individuals (the false positives) would be assigned to the treatment group, while the latter individuals (the false negatives) would be assigned to the control group. In that case, the experiment would show that the drug had an effect, even though it did not.

The first issue is how to define a causal effect. In the context of our simple model, let y(u, l0, t) be the outcome under the status-quo law in the next period, and let y(u, l1, t) be the outcome under the new rule, say an increase in the minimum wage. Let Δ = l1 – l0 denote the policy change. Following Holland (1986), we say that the policy change Δ at date t causes the effect:

D(u, Δ, t) = y(u, l1, t) – y(u, l0, t).

This definition is concrete: It is the difference in potential outcomes. In order to measure this “effect”, we would have to observe the same outcome for two different policies at the same time, something that is clearly impossible without time travel. Holland (1986) calls the impossibility of observing a causal effect the Fundamental Problem of Causal Inference. His analysis emphasizes the fact that measuring the causal impact of a treatment entails additional hypotheses.

Most solutions to the problem of causal inference rely upon versions of unit homogeneity or time homogeneity. By unit homogeneity we mean that there is a set of units U′ ⊂ U with the feature that the effect of the change Δ is the same for all u ∈ U, in which case the effect can be estimated by policy change to unit u1 ∈ U′ but not to unit u0 ∈ U′, in which case for u ∈ U′ we have:

D(u, Δ, t) = y(u1, l1, t) – y(u0, l0, t).

By time homogeneity, we mean that the effect of the treatment in different periods is the same. Hence, if we can estimate the effect of a treatment on a unit u by comparing the effect over time:

D(u, Δ, t) = y(u, l1, t + 1) – y(u, l0, t).

The challenge then becomes finding the homogeneous group. Regression discontinuity is an example of a recent popular technique that provides a way to create homogeneous groups that allow for the estimate of the effect of a treatment.40 For example, DiNardo and Lee (2004) argue that firms in closely contested unionization drives are almost identical in most respects. Because the outcomes of union certification votes are very close, one can assume that for these firms union status is randomly assigned. Consequently, we can compare the change in firm value for those firms that were unionized to the change for those that were not, and thereby procure a robust measure of the effects of unionization on a firm’s productivity.

Lee and McCrary (2005) provide an example of time homogeneity. Specifically, they look at the effect on behavior of sanctions against crime. Their study exploits the fact that when a person turns 18, they suddenly become eligible to be tried in adult courts, where they will face more severe sanctions than a juvenile court would impose. On the supposition that a person’s characteristics just before and after they turn 18 are the same, observed changes in crime-related behavior can be ascribed to changes in criminal sanctions.

Notice that all the work is being done by the assumption of continuity over time with the same union, or across units with very similar characteristics. The great benefit of this approach is that, beyond the continuity assumption (which is a strong assumption), this approach is relatively model-free. The problem is that while it may provide a credible measure of the effect of a policy change, the approach says little if one moves away from the point at which the policy change or treatment is applied.

A formal model in this framework has two distinct goals. The first is that it may provide a concise representation of a set of facts about the world. It describes the set of measured characteristics that one needs to know in order to capture the effect of a treatment. For unit u ∈ U, let X (u, t) ∈ Θ be a set of characteristics. In practice, one may not be able to measure all dimensions of Θ, but let us suppose for the moment that we can. Suppose u is a worker and we are interested in explaining worker wages. Then, we would say that a model that specifies a wage f(X, l, t) for a worker with characteristics X is an unbiased representation of the data at date t if for all u ∈ U,

ϕut = y(u, lu, t) – f(X(u, t), lu, t)

is an iid set of random variables with zero mean.

If our model is linear, we can let β(t, l) = ∂f/∂X, in which case we can write our model in the familiar regression form:

yut = β(t, lut)![]() Xut + ϕut.

Xut + ϕut.

If our model is unbiased, then this is a well-specified model that can be estimated by ordinary least squares. However, even if the model is well-specified, as Holland (1986) emphasizes, the coefficients of the model cannot be assumed to represent a causal relationship. For example, one of the parameters might be the gender of a worker, say 0 is male and 1 is female. If yut is the wage, and the coefficient on gender is negative, we cannot say that gender causes a wage drop. This is because gender is not a treatment or something that one normally assumes can be varied within a person.

We can use the coefficient on gender to test various theories. For example, human capital theory predicts that a person’s wage is a function only of their productive characteristics, such as schooling, ability, and experience. One reason women might be paid less is that they spend more time out of the labor force in child rearing. This reasoning implies that once the full set of characteristics reflecting productivity is included in X, then the coefficient on gender should be zero. If it is not, then we can say there is discrimination in the labor force.

A good theory specifies the set of parameters X that provide all the information necessary to describe wages while preserving time independence:

yut = β(lut)![]() Xut + ϕut.

Xut + ϕut.

Any variation in wages that occurs over time is explained via either changes in the parameters Xut or by changes in the environment 1ut. In practice, the econometrician may not have access to all the relevant information Xut, which leads to the well-known omitted variable bias problem in econometrics. For the present discussion, let us suppose that the relevant data are available and ask how the model can help in measuring the causal impact of a change in law l.

In general, economic theories do not provide precise point predictions; more typically, they make predictions about the sign of an effect. In the context of measuring the effect of the law on outcomes, the variation in treatment typically occurs either across jurisdictions—namely, the experiment assumes that all individuals in a particular jurisdiction u ∈ Us face the same legal environment lst,, and it is the legal environment that varies across jurisdictions. For example, many countries can be characterized as civil-law or common-law legal systems. We can let U1 be individuals in common-law countries and U0 be individuals in civil-law countries, and set ls = s.

In the example of civil- and common-law countries, one could estimate βs = β(ls) for each jurisdiction. In this case, the causal impact of the legal system depends on the distribution of characteristics of individuals in the economy. We would estimate the causal effect of changing from a civil-law system to a common-law system for regions that are currently under civil law in period t by:

![]()

In order to estimate the causal effect of a change in the legal system, one needs to use the characteristics of the jurisdiction where the change is to occur. This adjustment is a version of the well-known Oaxaca decomposition, which is widely used in studies of income inequality (see Altonji and Blank (1999)) and union wage differentials. As we discuss in more detail in Section 4, this is not the literature’s usual technique. The more common assumption is that the effect of a policy is linearly separable, where for u ∈ Us we have:

![]() (1)

(1)

Using data for a single period t, then, we can estimate the average effect of the legal system on the wages and employment of individuals by:

![]()

The goal of the theory discussed in this section can be summarized as follows. The theory makes predictions regarding the characteristics X that are needed to represent individual outsources. In particular, it will provide predictions regarding how variations in individual characteristics relate to variations in outcomes. Theory has predictive power if we can safely assume that the relationship between the Xs and the ys is stable over time.

A theory has more predictive power if one can represent outcomes using a smaller set of Xs. Given the difficulty of obtaining good measures of individual characteristics, theories with fewer Xs are inherently easier to test. On a related note, there is a line of inquiry in statistics that attempts to be model free. This is achieved by supposing that one has a rich set of X variables and that the environment is inherently continuous; as a result, good representations of the data can be used to make predictions on how changes in an individual’s Xs will affect outcomes. Breiman (2001) suggests that such an approach is sometimes more feasible given present computing resources and the large data sets we have in some domains.

However, representation is not causation. Many individual characteristics are not amenable to experimental treatment. Making causal statements requires that we assume we have a valid representation of the data that allows one to compare outcomes either: (1) across units with similar characteristics but in different treatments, or (2) the same units faced with different treatments over time. In these cases, the theory—in addition to specifying the relevant X variables—also specifies an explicit mechanism by which the law affects the actions of individuals, and hence how one can obtain a valid measure of the causal impact of a change.

3.2 Economics of the employment contract

This section discusses the literature that seeks to explain the form and function of employment contracts. Fundamentally, parties who enter into a contract have agreed to have their behavior constrained in the future. The most basic reason for a contract is to support inter-temporal exchange, something that cannot be avoided in the context of labor services. For example, a day laborer agrees to work eight hours in exchange for a wage at the end of the day. When it comes to paying, the employer may have an incentive to renege or attempt to reduce the agreed-upon wage. One role of the law is to enforce such agreements.

In economics, such simple exchanges are typically assumed to be enforceable. The literature has focused on explaining the form of observed contracts that address one of three more subtle issues:

1. Risk. Demand for a worker’s services, and hence wages, is likely to change from period to period. Risk-averse workers would like to enter into long-term contracts that would shield them from such shocks.