It is the goal of every good CIO to align IT strategy to business strategy. No rational businessperson today would argue this premise. However, this simple premise is harder to achieve than is readily apparent. What IT needs to build and deliver to achieve the goals of business strategy can be difficult to identify, and highly debatable depending on one's point of view within the enterprise. IT systems can be abstract, complex, and difficult to understand. Business processes, enabled by systems, can suffer from the same challenge. An enterprise will have a collection of systems created by different people at different times under different sets of information, constraints, and decisions. Parochial interests of different business units, departments, and key managers can also confound the issue. It is no wonder that an organization can sometimes feel that its IT systems, processes, and people are not in synch with its current strategy and goals.

The CIO, IT staff, and other business leaders and staff need to be able to see and understand alignment between IT and business strategy. They need to be able to understand the elements that create alignment and understand their relationship and contribution to those elements. And, based on this understanding, they need to become the champions of the correct behaviors and processes that lead an organization to its alignment and strategy realization goals.

The CIO faces an intimidating task aligning an IT organization and a steady stream of large, complex, and risky IT investments to the constantly evolving and adapting business strategies of an organization. Many CIOs have found this goal elusive and difficult to achieve and behaviors and expectations in other parts of the organization often exacerbate the problem. What is needed is a set of guiding principles, processes, maps, guideposts, and milestones that communicate and align IT to the business strategies, which guide both IT and the business.

Once business strategy is set, the challenge becomes how to go about aligning IT strategy with business strategy, and doing it in terms that can guide and manage expectations for both the business and IT. This multifaceted challenge requires many disciplines and practices to achieve. There is no one single construct or technique that enables this alignment. Organizational decisions and behaviors need to support and lead to alignment, and this is not a natural process for most organizations. Achieving alignment means choosing the right IT investments, building them the right way and implementing them at the right times to achieve the enterprise synergy and business goals being sought. The ability to actually execute and deliver the initiatives is the difference between success and failure. And, the different systems and processes created need to integrate and create a whole that is greater than the sum of the parts.

CIOs have several fundamental, interrelated, and often poorly understood disciplines at their disposal to align IT strategy to the business strategy. Enterprise architecture, IT governance and portfolio management, and organizational development constitute the primary set of practices that enable the CIO to achieve alignment in a constantly changing business environment.

The tools and techniques in these three primary practice sets revolve around three long-standing core concepts well known in the systems development disciplines, and which have parallels when one seeks to build and enable an enterprise. People, process, and technology have stood the test of time as the fundamental, necessary components of successful business solutions. As technology becomes more ubiquitous and as technologies continue to commoditize, emphasis has evolved toward people and processes as the focal areas for gleaning return on investment and competitive advantage from IT investments.

Successful CIOs necessarily train their sights on the business and enterprise level and keep their perspective focused on this horizon. The CIO needs to be squarely focused on strategic business goals and enabling and aligning IT to reach those goals. Bringing the focus on people, process, and technology up from the systems/project level and applying it to enterpriselevel IT and business alignment gives the CIO a focal point for IT alignment and the realization of business strategy. People, process, and technology manifest themselves at the enterprise level as IT organizational development and delivery model (people), IT governance and portfolio management (process), and enterprise architecture (technology and related business process). The disciplines in these three primary practice areas become the focus for CIOs entrusted to lead IT and enable business strategy, focus on the customer, and make their organization more competitive in the marketplace. CEOs often state that what they most want from their CIO is the ability to achieve this alignment. In other words, what the CEO wants most is the CIO who can lead IT to achieve the realization of business strategy.

The realization of business strategy takes place over long, multi-year periods of time. This is especially true when the strategic goals include profound change or new business models. CIOs who lead by facilitating and enabling these long-term strategies use methods and approaches that endure the challenges and environmental threats posed by long-term change, and that outlast an all too common short-term view on specific projects, implementations, and tactics. The CIO's methods must accommodate key personnel turnover, changing and competing business and technology priorities, business environment changes, and the need for ever-increasing business agility and flexibility. At the same time, the CIOs must articulate the strategic implications of IT methods so that people at all levels of the business understand how the IT architecture supports their strategic decision making and guides the organization to its stated objectives.

This chapter is written for the IT leader who seeks to concretely and comprehensively support the realization of business strategy through information technology. Specifically, this chapter discusses the interrelated relationships of architecture, IT governance and project portfolio management, and IT organizational development in terms of how their interrelated synergies create a powerful whole, greater than the sum of their parts. This chapter focuses on the key interrelationships of these three practice area disciplines and how the CIO can integrate them to guide the organization in support of enterprise strategic goals.

CIOs who establish a strategic IT presence at the leadership table bridge the gap between business strategy and the information and technology structure of the organization. At any given point in time, the state of information and technology may not represent what is most important to the organization. As strategic goals change, there is an inherent requirement for flexibility and agility on the part of IT and on the enterprise to adapt as detailed in Chapter 3. The requirement to rapidly adapt to change has become a critical differentiator for competitive, high-performing organizations. Building an agile, adaptive IT organization that constantly works to bridge and minimize the gap between the current-state of information technology and the optimal state required to meet the organization's strategic goals is the name of the game for the best practice CIO.

A series of interrelated practices and disciplines enable the CIO to bridge this gap and directly tie the elements of business strategy to IT investments. Best practice CIOs understand and communicate the current architecture of IT infrastructure, applications, and information for their enterprise and articulate a future-state to be achieved based on the business goals, strategies, and current technological opportunities. They identify the gap between current capabilities and the future-state required to reach strategic goals, and they demonstrate the path to reach the future-state where the strategic goals can be achieved in terms of information technology, processes, and people. However, defining and communicating the current-state, future-state, and gap is only the beginning. The best practice CIO guides organizational behaviors, decision making, and capital budgeting to lead the organization to the destination.

Best practice CIOs also control and influence IT investment decision making to ensure that the right investments are being made, that these investments are being made at the right time and in the right order, and that these investments and solutions are being constructed correctly to support strategically aligned IT architectural standards. These discrete IT investments need to be managed in unison as a balanced portfolio that supports consciously designed enterprise milestones and targets. Business outcomes that result from a correctly aligned IT investment portfolio lead directly to the realization of business strategy.

The best practice CIO delivers these results through people and the IT services delivery model, leveraging in-house staff, vendors, consultants, and outsourcers. Organizational development must align and support the specific skills and services requirements of the enterprise architecture and IT project portfolio. This organizational development requirement is equally true for departments outside the IT function or the CIO's direct control.

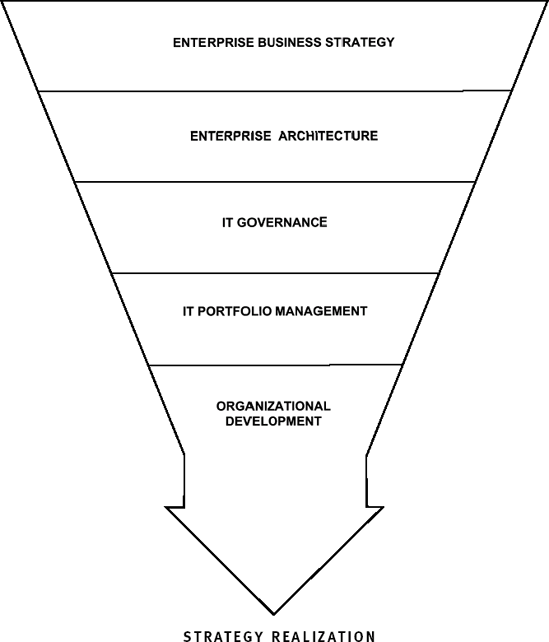

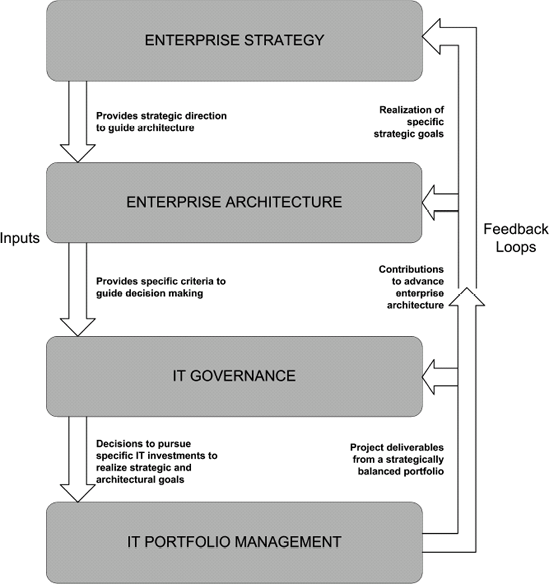

This continuum of disciplines and processes can be viewed as a funnel that starts from the broad, overarching goals of business strategy and then moves down through a progressively narrowing set of processes, designs, and managerial disciplines leading to the right set of projects designed around the right architecture and delivered by the team with the right set of strategically aligned skills, objectives, and incentives. It is one of the fundamental skills of the CIO to be able to navigate the organization down this funnel leading to the realization of business strategy enabled by IT (see Exhibit 2.1). The funnel's path guides the CIO through the critical IT management disciplines that bridge the gap between business strategy and the realization of strategic goals.

As discussed in Chapter 1, business strategy today cannot be realized without information technology. The CIO and the IT organization are uniquely positioned in the enterprise to be able to articulate how a business will achieve its strategic goals, at least from the standpoint of technological capabilities, information, processes, and the customer experience. IT generally enjoys the broadest view on an enterprise at the operational level, enabling valuable insight into intra- and inter-enterprise processes, information requirements, operational challenges, and technical requirements. In addition to designing and managing customer-facing systems and Web sites, IT often maintains close relationships with support and sales operations, all of which create the "customer experience" for the diverse constituency base of an enterprise. This becomes especially true when much of an enterprise's business is conducted online through e-commerce and self-service vehicles. All of these experiences and visibility give IT and the CIO a unique and broad perspective on what is required for an organization to reach the goals called for by its strategy.

It has been said that great leaders "illuminate the road ahead". As a leader, the best practice CIO articulates and illustrates what technological, process, and business capabilities the organization requires to reach its goals. As solutions providers, CIOs demonstrate the nature and structure of the solution that enables IT customers to reach their goals in terms they can understand. And the CIO needs to be positioned to continually reinforce and communicate the vision and to execute the difficult task of guiding the organization through periods of strategic evolution.

One of the tools of IT customer illumination in the CIO's leadership arsenal is enterprise architecture (EA), which provides the organizational, process, information, and technology roadmap for enabling the capabilities required to achieve the enterprise's strategic goals. It is the job of the CIO's organization to be able to communicate and illustrate how and through what technology, information, and process mechanisms the organization will achieve its strategic objectives. Enterprise architecture is a foundational approach to achieving this leadership requirement. To put it another way, the CIO's enterprise architecture should be the information, technology, and process manifestation of the enterprise business strategies.

To understand the application of enterprise architecture to the realization of business strategy and why it is an important best practice for the CIO, it is helpful to begin by looking at a few of the definitions of EA. Organizations can approach the definition and positioning of enterprise architecture in differing ways. For some organizations, the focus of architecture is technical while others take a focus on information, business processes, and organizational structure. Enterprise architecture can be approached top-down as enterprise-wide or driven bottom-up from a project and initiative level. Perhaps the most effective approach is a balance of the two.

The final whitepaper for enterprise architecture for the U.S. Chief Information Officers Council describes it this way: "Enterprise Architecture (EA) links the business mission, strategy, and processes of an organization to its IT strategy. It is documented using multiple architectural models or views that show how the current and future needs of an organization will be met . . . In essence, the EA defines the target architecture at a given point in the future that is necessary to support the business mission and strategy of an organization."[9]

The Meta Group (now part of Gartner Group) used the following definition: "Enterprise Architecture is the holistic expression of an organization's key business, information, application, and technology strategies and their impact on business functions and processes. The approach looks at business processes, the structure of the organization, and what type of technology is used to conduct these business processes."[10]

Although there is no single, universally accepted definition of enterprise architecture, they all attempt to describe the concept of linking an organization's information, processes, and technology to its strategy. To address how EA helps the CIO integrate multiple managerial disciplines to reach organizational goals, the previous definitions can be complemented with a higherlevel, cross-functional definition of the role of enterprise architecture:

Enterprise architecture provides a foundation for effectively integrating IT governance, IT portfolio management, and organizational development. These disciplines are necessary to create and align the IT capabilities that bridge the gap between business strategy and the realization of strategic goals.

With this added dimension, it becomes important for the CIO to understand the best practices of enterprise architecture and how to approach and integrate the discipline of enterprise architecture in ways that are appropriate and achievable for the enterprise and IT organization. IT capabilities and the architecture of the enterprise determine the CIO's ability to enable business strategy. Enterprise architecture defines IT and business capabilities required by articulating and modeling the future-state required to realize the goals of business strategy. EA is the link between strategy, technology, processes, and organization and is one of the key IT contributions to the enterprise effort to implement strategy.

Best practice CIOs develop the skills to "think like an architect" when viewing the enterprise IT landscape. Like it or not, consciously designed or not, the CIO has an architecture, and the job responsibilities call for reshaping the architecture to the optimal state to achieve the strategic objectives. Leading with architecture positions the CIO to tangibly align IT through architecture's necessary and required contributions to IT governance and IT portfolio management processes just as it aligns the structure of the organization's information technology and processes with the business landscape.

The analogy of city planning is very useful to provide a ground for what enterprise architecture is and illustrate why it is important. A city plan describes the architectural constructs, policies, and standards that guide individual building initiatives and defines the standards for shared and common services such as traffic, roads and transportation, utilities, and open space. City planning provides the framework within which multiple individual projects and architectures (sub-architectures) exist. City planning further focuses its frameworks into zoning controls, which define the standards and policies for specialized types of sub-architectures such as residential, retail, or industrial uses, or different types of shared services such as electricity, utilities, and roadways.

Planned communities establish standards that guide development as the first order of business. Established cities create similar standards and plans for new construction, renovation, and expansion within and beyond current city boundaries. Cities create specialized roles for city planners, establish building codes and standards for construction and services, establish procedures for obtaining building permits, and have processes for enforcing adherence to these codes and standards. The goal of city planning is to ensure that buildings and shared services will work together to meet the goals of safety, efficiency, aesthetics, and livability established by the members of the community.

Enterprise architectures are created and adopted to meet analogous goals for the enterprise. The multitude of systems in an organization need to work together, share data, provide information security, scale and adapt to change and growth, reduce overall costs, and allow the organization to reach its strategic goals. Enterprises need guiding and constraining architectural designs and standards with policies and processes for approval and enforcement of these standards for individual initiatives.

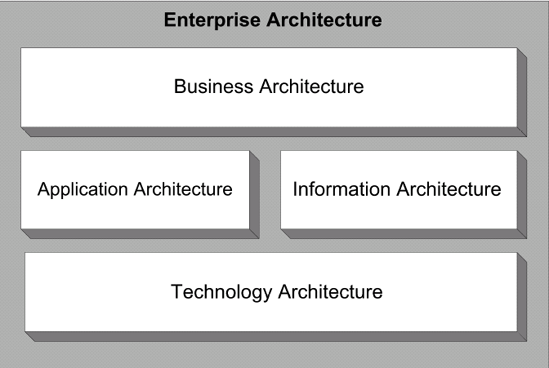

Enterprise architecture can be further characterized in terms of the major architectural and process tiers used to categorize broad areas of IT and business architecture. The best practice CIO establishes these tiers, equivalent to planning "zones" in the city planning example, within which to establish and document architectural standards. Within an enterprise architecture, these tiers can include both business and technical architecture constructs.

CIOs may focus on some or all of four areas, and define new areas appropriate to their organizations or the enterprise architectures methodology they have adopted. The four universally accepted enterprise architecture domain tiers are business, technical information, and application (see Exhibit 2.2).

Business architecture describes the enterprise's structural, high-level business processes, service areas, and delivery channels. It defines the functional roadmap for the organization. It may describe processes like procure-to-pay, order-to-cash, and recruit-to-hire for a commercial business. In a university setting, business architecture describes processes like prospect-to-student or student-to-alumni process flows.

Technical architecture describes the infrastructure and network architecture. This category includes IT security architecture, networking and communications infrastructure, servers, storage, operating systems, personal computers, and other end-point devices such as PDAs and cell phones.

Information architecture describes the enterprise data model, database architecture, and content and knowledge management architectures. This can also be the tier where data and application integration is defined, but they can also be treated as a separate dedicated tier.

The applications tier describes the applications and application architecture required to support the requirements of the business architecture. The presentation layer, or "customer experience" architecture could be described here or treated as a distinct architectural tier. The presentation layer should integrate the user experience into a common gateway for interacting with the enterprise. This becomes especially important as e-business and e-government initiatives continue to create online, selfservice access to data and services.

This chapter is not meant to be a detailed treatise or primer on the various EA methodologies and frameworks that exist. However, a discussion of how to approach EA methodology is warranted. The CIO can choose between many methodologies, and they all have differing approaches to the challenge of quantifying, organizing, and describing the architecture of the enterprise. Variations between methodologies include different taxonomy for describing the architectural tiers, objects used within the models, repository architectures, and the approach to the modeling and analysis task. All of the models of enterprise architecture, however, describe both functional and technical architectures. Choosing a particular methodology is an important undertaking. It is also important to bear in mind that it is not required to choose a formal EA toolset and methodology to develop and maintain an effective enterprise architecture. What is most important is choosing a consistent way to describe the architecture that is accessible and agreed upon in throughout the enterprise. The scale of the enterprise has a significant impact on the need for a formal EA methodology.

Large enterprises usually have sufficient people, skills, and financial resources to invest in a formal EA methodology and toolset. The size and scale of the EA effort in the large enterprise, combined with the broad constituency base of the EA outputs, warrant this approach. There are also attempts to drive inter-enterprise EA standards within industries, such as the U.S. Federal Government, which has established the Federal Enterprise Architecture (FEA) methodology to which all federal agencies are mandated to adhere.[11]

For the small and medium-sized enterprise, the choice is often less clear. There are advantages to being "methodology light", especially for the small and mid-size enterprise. The complexity and cost of full-blown EA tools and methodologies can often be significant impediments for beginning an enterprise architecture program. The use of well-known charting and illustration tools like Microsoft Visio and flowcharting and data modeling tools are often sufficient to implement a highly effective EA program while facilitating adoption and keeping costs low. However, the CIO still needs to choose an EA approach and how to structure the practice. One excellent resource for the "methodology light" approach is the IT Architecture Toolkit,[12] which describes a practical and simple approach to delivering on the promise of enterprise architecture utilizing readily accessible tools and methods. Other widely used approaches to EA methodology include:[13]

Zachman Framework for Enterprise Architecture[14]—A framework for describing enterprise architectures. It is one of the original EA frameworks and is widely adopted.

TOGAF[15]—The Open Group Architecture Framework is an industry standard architecture framework that can be used freely by any organization.

FEAF[16]—Federal Enterprise Architecture Framework, developed by The Chief Information Officers Council of the U.S. Federal Government, is an EA framework designed to be used by all federal agencies in the United States.

One of the CIO's most significant challenges is determining how to organize the enterprise architecture practice. Does the EA practice require a dedicated staff or can non-dedicated staff lead architecture? Should the EA group be a separate organizational unit or be part of the technical and operational units of the IT organization? What are the characteristics and skill sets of the architecture practice roles, and what are the different roles across the spectrum of enterprise architecture?

There are many ways to achieve the benefits of enterprise architecture and to structure the practice. Perhaps the biggest determinant guiding which form EA takes is the size of a firm and the amount of available financial and personnel resources that can be applied to the EA function. Another key criterion is the vision and the appetite that the CIO and other stakeholders have for enterprise architecture (and planning in general) and the role they accord EA in their business.

Small and mid-market organizations face unique challenges when attempting to incorporate enterprise architecture. Perhaps the most fundamental challenge is how the EA function gets funded (i.e., are there enough resources to create a dedicated EA group). The CIO also needs to ascertain if the size and complexity of the enterprise actually warrant a dedicated EA group.

In my experience in mid-market organizations, while a dedicated team of architects would certainly be desirable it is not actually necessary to reap the bulk of the benefits of enterprise architecture. Although compromises may need to be made in the purity of the EA practice, thoroughness of the EA artifacts, and the life cycle within which those artifacts are kept updated, the majority of the benefits of EA can still be achieved. The architecture practice and analysis is still critical in the mid-market organization, but the analysis and planning can be incorporated into the role of key, skilled people on staff, including the CIO. CIOs in these mid-market organizations may need to perform the role of chief enterprise architect, while their technical managers perform the role of domain architects over business architecture, technology, information, or applications. The hiring and cultivation of these skill sets becomes a critical success factor for bringing enterprise architecture into the mid-market organization.

For example, Golden Gate University (GGU), as a mid-size organization, doesn't enjoy sufficient resources to create dedicated architecture roles. However, the university is keenly aware of the benefits of architecture and has incorporated enterprise architecture into the IT organization's governance and project portfolio management practices. As a result of leading IT from the architectural perspective, we focus on hiring and developing IT staff who can function as architects in their domain areas, although they may not carry the title of "architect". My role as the CIO has included the functions normally associated with what would be called the chief enterprise architect in a larger organization. All of our IT staff members need to be either technical or managerial performers, and the best also take on architectural responsibility. In fact, to be considered an architect of a domain area becomes a source of pride and leadership, as well as a significant career development step for the individual IT professionals. As discussed later in this chapter, creating architecture responsibilities and aligning skills development with the enterprise architecture is a positive career development practice for IT staff. The breadth of skills required across all the domain areas of the enterprise architecture practice make this positive aspect true for both technical and managerial career tracks.

Benefits of this approach include significant cost efficiencies by not employing dedicated architectural staff, while still realizing most of the benefits of enterprise architecture. GGU has also found that architecture stays "close to the ground" and is firmly ingrained into IT governance and the systems development life cycle (SDLC). As opposed to environments with separate architect and IT teams where there can be significant antagonism between the groups, the leaders of the GGU IT technical domains firmly believe in the importance of architecture and actually become frustrated when architectural directions are not clear enough. This approach also avoids the "ivory-tower" syndrome where the architecture practice is divorced from technical IT.

As in environments with dedicated EA architects, IT organizations without dedicated architects should still organize the architecture roles around the core components of enterprise architecture: business architecture, technical architecture, information architecture, and applications architecture. This often follows the natural organizational structure of many IT departments and should make it easier and more natural to create an EA practice.

The best practice CIO of the small or mid-market organization instills architecture and architectural skills as a core competency as much as possible. Without a dedicated architecture team it becomes necessary to instill the skills and discipline across people who have other duties. Make architecture skills and an understanding of the enterprise's current- and future-state architectures a core competency in the IT organization and not only the domain of "architects". A parallel can be drawn with the project manager role in the small and mid-size organization; the role can be difficult to staff on a full-time basis. This situation requires two tactics: (1) Develop project management skills in domain area managers so they can manage projects, and (2) Contract IT project management specialists for unusually large projects requiring specialized project management skills beyond that of internal teams or that require full-time attention for discrete periods of time.

Similarly, many organizations can function quite well and reap many benefits of EA without staffing full-time architects. Domain area managers with architecture skills can provide tremendous value to an organization and keep much of the architecture responsibility moving forward. For special architectural challenges that require advanced skills for discrete periods of dedicated time, specialized EA consultants can leverage internal team skills in these situations. The internal architects maintain and advance the initial architectures created by the consultants. In this way the CIO reaps the benefits of EA, aligning IT to strategy via EA, IT governance, and IT project portfolio management without the requirement to staff full-time architects. Remember, enterprise architecture is not solely the domain of the large enterprise with a lot of resources. With a good team and an awareness of all the options, a creative CIO can accomplish similar goals in a smaller organization.

Enterprise architecture accrues the same benefits to organizations large and small. However, large organizations have significantly greater complexity and have both unique challenges and opportunities when developing their enterprise architecture practices. The need to have dedicated teams, formal methodology tools, volumes of artifacts, documentation, and EA-specific processes are more significant in large organizations. Challenges are also greater in large organizations when incorporating enterprise architecture into the operating processes of the enterprise, IT governance, IT portfolio processes, and the SDLC. Many of the frustrations architects face with large organizations stem from the challenges of EA integration into IT governance processes and a lack of alignment or appropriate enforcement and decision-making authority. Best practice CIOs in large organizations pay particular attention to these areas to position enterprise architecture for success and fully reap the benefits of enterprise architecture.

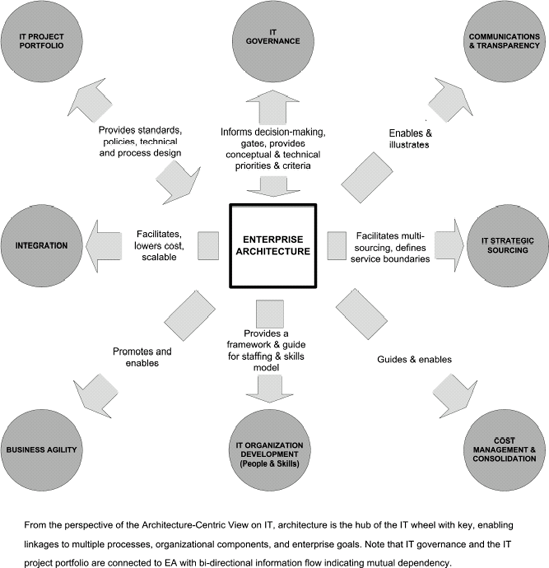

A sound, well-executed enterprise architecture provides significant value and benefits for the CIO and the enterprise. Enterprise architecture propagates concentric waves of information influence throughout the organization and significantly impacts IT capabilities. Through direct, bidirectional linkages to IT governance and IT project portfolio management with impacts on costs, human capital management, outsourcing opportunities, communications, and leadership, enterprise architecture is one of the most important functions for the CIO and IT today (see Exhibit 2.3). EA plays a critical role as the CIO leads the organization down the Business/IT Strategy Realization Funnel. The next sections explore some of these areas and discuss their impact for the CIO.

At the highest levels, a good enterprise architecture provides a fundamental basis for decision making as a part of the firm's IT governance processes. Architectural requirements serve to define and prioritize the most important projects in the IT project portfolio. As the architecture defines the IT components and capabilities required to reach the organization's strategic goals, the projects that spawn from the architecture align with business strategy and focus on building the most important capabilities to exploit the best business and technology opportunities—if IT governance is working well. Part 2 of this chapter treats this interrelationship in greater detail.

Cost Reductions and Efficiencies

A sound architecture helps to reduce costs by enabling systems consolidation and increasing IT investment leverage. With a common architecture, investments in standardized infrastructure can be reused across many projects and applications. Standardization helps drive cost efficiency by reducing the number of disparate platforms to support, which, in addition to reducing the numbers of vendors and contracts, provides a direct impact on the efficiency of the IT organization as the staffing model becomes more tightly aligned with the corresponding technology architecture. With a standardized architecture, the IT organization delivers a greater number of projects through its ability to leverage previous investments, reducing or eliminating the need to make core infrastructure investments for business-driven initiatives. Additionally, a strategically aligned EA creates efficiencies in IT operations and systems management, reducing costs in these expensive IT areas.

Clarity regarding the contents of the IT portfolio serves to eliminate redundant assets and create visibility into software application overlicensing or under-licensing, reducing either direct costs or liabilities. Driven by the standards and policies spawned from enterprise architecture, CIOs more easily see investment overlaps in the IT project portfolio that can significantly reduce redundant IT investments, positively influencing capital budgets available for IT investments or redeployment elsewhere in the organization. The cost savings realized for both operating and capital budgets can be redeployed into higher value projects and increase the innovation capacity of the organization.

Payback from Architecture Investments

With a strategically aligned IT architecture in place, most of the IT project portfolio can shift to business-facing projects where there is a higher payback. The impact of IT increases for the enterprise as a direct result of pursuing a consistent architecture, and migrating away from systems and applications that do not conform whenever possible. In addition to the direct savings from systems and IT portfolio consolidation and IT staffing model alignment, a significant part of the payback from architecture investments generally comes from the reduced cost of subsequent businessfacing projects. To keep the architecture investments justified, the best practice CIO explicitly quantifies and communicates the benefits of the architecture investments and ties those investments back to current and future project proposals and cost savings, which leverage the architecture. This communications practice keeps the value of architecture visible and relevant while continuously demonstrating the value that IT brings to the organization.

Increasingly, organizations look to outsourced services to fulfill their IT mission. A solid architecture is an important component of successful outsourcing. Systems and process environments that look like a plate of spaghetti are very difficult to outsource cost-effectively. A good architecture facilitates outsourcing via clear system and service boundaries, resulting in an enhanced ability to multi-source across a variety of outsourcing vendors while maintaining project and architectural control in-house. A solid architecture becomes even more critical as outsourcing influences a loss of "institutional-memory", and a short-term, profit-motivated, project-level focus on the part of the outsourcers delivering the projects. Outsourcing by its nature causes a shift of systems knowledge away from internal staff to the services provider. Without the blueprint of a solid architecture, an organization runs the risk of losing control of the enterprise view on IT and experiencing corresponding difficulties coordinating the disparate efforts of multiple service providers. Additionally, the short-term, project-level focus of most service providers further exacerbates this problem. It is not in their short-term interest to explore all the enterprise ramifications of systems development or change, but instead rely on the client to provide this control and oversight. A solid enterprise architecture becomes a requirement for organizations wishing to leverage outsourcing, especially given the trend toward multi-vendor outsourcing, which requires greater clarity in servicelevel boundaries, delivery hand-off points, and enterprise-wide coordination. See Chapter 7 for more outsourcing considerations.

A sound architecture simplifies the IT organization, increases its flexibility, and allows the same number of people to deliver more IT services and capability. Higher levels of IT delivery throughput and an architecture that provides leverage to subsequent investments lead to greater IT agility and flexibility. See Chapter 3 for an in-depth treatment on how to achieve an agile IT organization.

Another way to look at the value of a sound EA is through its influence on "innovation capacity", which refers to the capacity of IT to create new value for the enterprise in the form of new opportunities, products, and services. As IT succeeds in reducing the amount of time and money spent on IT operations, the redeployment of both human and financial IT assets to innovation creates new value for the enterprise.

A demonstrable example of the power of enterprise architecture, combined with IT portfolio and project management processes, comes from Golden Gate University where IT enabled an e-business transformation of the university, taking it from a static, offline model to a dynamic, Webenabled, data-driven, online model. At the beginning of the transformation, many new significant IT and business capabilities were determined as requirements for carrying out the rapidly evolving business and educational mission. We spent many months up front, before starting a lot of new projects, defining our architectural approach and looking at key business process areas thatwould be affected and need to evolve to meet the goals of the e-business model. We assessed our current-state and planned and designed our future-state of technology, information, and business architectures in the initial key areas that would be affected first. Along with architectural design and planning, we also worked hard within the IT organization to implement an IT portfolio and project management practices for the first time.

The eventual result was an estimated ten-fold increase in the number of information technology projects the university could realize in a given time frame when compared to the same time frame prior to the architectural upgrade. And the trend to greater speed has continued as the university continually leverages previously constructed architectural components to deliver new projects faster and less expensively. Three years after beginning the EA initiative, the university has fundamentally reengineered departmental and customer-facing processes and technologies in time frame order of magnitude faster than in the past. From the CIO's perspective, IT applications projects now feel almost easy. The EA investments built prior leverages current initiatives, and little to no infrastructure needs to be created. This new ability to predictably and repeatedly deliver significantly greater numbers of new initiatives has meaningfully increased the business agility of the university and its ability to adapt to changing conditions in the higher education marketplace.

Communications is a critical component of every CIO's success. It is necessary for the CIO to describe the roadmap ahead for IT and how IT will enable their business strategy. The written goals, documents, diagrams, plans, and standards and policies of enterprise architecture are strong written and visual communication tools for the road ahead. These EA tools sell the vision to senior management and other stakeholders and manage expectations regarding IT investments. As an ongoing process that requires repetition and updating if learning and change are to be affected, use the tools of enterprise architecture in communications by posting them on your intranet and keep the architecture and roadmap visible to the IT organization's constituency to illuminate the road ahead and lead with your strategically aligned enterprise architecture.

One of most powerful outcomes of a solid enterprise architecture is its positive impact on the development of the IT organization and the individual IT professionals. Because enterprise architecture defines the future-state of information technology in the organization, it creates a set of goals for both the IT organization and its individual staff members to target. Required organizational capability, individual skills, and career development plans become much more clear, and gaps between existing skills capabilities and required skills capabilities in the future become apparent. This clarity and visibility into future skills and staffing requirements give the CIO, the IT organization, and other areas of the enterprise, the roadmap for skills and career development, hiring plans, and strategic sourcing decisions. The future-states of the architecture clarify which functions are more commodity-like (becoming candidates for outsourcing) and which functions are more strategic and warrant inhouse development of skills and talent. Given that skills development and acquisition and staff retention are long-term challenges, the visibility provided by a clear enterprise architecture becomes invaluable. Part 3 of this chapter takes a deeper look at how the CIO can work to align career development planning within the IT organization with enterprise architecture.

As mentioned at the start of this chapter, there is no single construct or technique that enables the CIO to align IT to the business and facilitate the realization of strategic objectives. An enterprise architectural plan is only the beginning of realizing the business goals. Although enterprise architecture defines what IT capabilities are required to reach strategic goals, architecture by itself is not enough to bring about the required changes and organizational behaviors that result in the desired outcomes from IT investments. Many of the significant struggles that enterprises face in realizing the goals described by their enterprise architectures are born from the challenge to effectively link architectural goals to the specific projects that create the IT capabilities being sought.

The CIO has a difficult, if not impossible, time working to realize the goals specified by the enterprise architecture without supportive, interrelated processes and disciplines working in concert. The CIO needs an approach and set of procedural disciplines to link the outcomes of enterprise architecture to the realization of business strategy on a consistent and ongoing basis.

Enterprise architecture has a direct, dependent, and synergistic relationship to two other core disciplines of the successful CIO: (1) IT governance and IT portfolio management, and (2) organizational development (the development of human capital). The stewardship of the CIO leads the IT organization through these processes so that the enterprise can realize its business objectives.

Symptoms of an enterprise architecture that is poorly aligned to the organization are many. (1) Architectural plans are created, but IT projects are implemented without adhering to the architecture. (2) Architecture is not integrated into the IT governance decision-making processes, thereby allowing projects to get approved without complying with the architectural guidelines or standards. (3) Architecture becomes political in one of two ways. First, different parties fail to adapt to the architectural guidelines, creating resistance and a lack of consistent compliance. Second, architecture becomes a political bottleneck to approving projects, unnecessarily slowing down project life cycles, which results in people trying to figure out ways around the architecture process. (4) Investments in enterprise architecture are seen as providing insufficient or nebulous payback and fail to get approved. (5) Architecture efforts are not tied to the business initiatives born from business strategy and are interpreted as unaligned, ivory-tower, or impediments to rapid execution of individual projects.

The symptoms just listed are neither exhaustive nor uncommon. Dysfunctional symptoms like these result from improper relationships and alignment between architecture and the processes of IT governance and portfolio management. Best practice CIOs effectively reach enterprise strategic goals by correctly aligning these processes into a complementary synergy.

IT governance and project portfolio management constitute the glue—the procedural linkages—required to marry the enterprise architecture function into IT decision making, program and project management, and budgeting. The topics of IT governance and portfolio management are broad and have a number of definitions and interpretations. The seminal book, IT Governance:How Top Performers Manage IT Decision Rights for Superior Results, defines IT governance as "Specifying the decision rights and accountability framework to encourage desirable behavior in the use of IT."[17] The authors further break down the concept of IT governance as defining "mechanisms formalizing the relationships and providing rules and operating procedures to ensure that objectives are met."[18] This distinction begins to illustrate the direct link and dependency between effective IT governance and effective architecture. In other words, without a governance mechanism to establish rules and operating procedures it becomes difficult or impossible to enforce architectural standards.

Another definition of IT governance further aligns the conceptual link between strategy and the requirement to control the implementation of IT strategy, hence, architecture: "IT governance is the organizational capacity exercised by the board, executive management, and IT management to control the formulation and implementation of IT strategy and in this way ensure the fusion of business and IT."[19]

Comprising a subset of the practices of corporate governance, the topic of IT governance is very broad. This discussion focuses on IT governance processes that enable the CIO to tangibly align IT decision making with enterprise architecture and how the CIO manages the process of decision making to specifically realize the goals of the enterprise architecture. The best practice CIO establishes a process for architectural governance that clearly positions architectural decision-making authority while also providing a process for managing exceptions. There are essential elements of this process for the CIO to consider.

The CIO's role is to gain senior leadership support for architecture. If architecture is going to become a critical forum for deciding which IT investments gain approval and to what architectural standards those investments are constructed to and constrained by, then it is mandatory for all leaders involved in the IT decision-making process to understand the value of a correct and strategically aligned architecture and the role of architecture in IT investments. Without this common understanding among key IT investment decision makers, the best practice CIO starts with education and communication regarding the value of the architectural approach to IT. Buy-in is critical because IT investment proposals need to be vetted against architectural standards and approved, rejected, or sent back for rework. Without senior leadership understanding of the important role of architecture in achieving business goals, the CIO continually fights a series of difficult battles in the process to lead IT decision making to achieve desired outcomes.

Best practice CIOs incorporate architectural review into the IT investment evaluation process. An effective strategy to facilitate this is to create an architectural review board, which is responsible for leading the creation and governance processes for architecture and vetting project proposals for compliance to, and advancement of, the enterprise architecture. Even in small and mid-sized organizations that may not warrant a formal "architecture board", the CIO should establish the key architectural leaders and loop them into this process. Project proposal documentation should be upgraded to include an architectural assessment for fit and compliance to internal standards.

Only in a perfect world would every project conform to an organization's architectural standards. One of the most important elements of architectural governance is a process for managing exceptions. The business inevitably encounters requirements that are best met by a solution that is not architecturally conformant, and architectural standards have to compromise. The most common exception-management process escalates through the managerial ranks. Each enterprise should design an architecture exception-management process to standardize the dispute resolution process. For example, if the project requestors and the architectural reviewers cannot agree, the issue escalates to the CIO. If there is still an impasse after CIO-level mitigation, the issue escalates higher to the next level of the official sequence, all the way to the CEO in some enterprises. Obviously, for reasonable architecture disputes to escalate above the CIO there must be a strong and common knowledge about the role and importance of enterprise architecture among the senior managers. When an architecture exception-management process includes the CEO as the final arbiter, it underscores the importance of enterprise-level architecture and it makes the business (not just IT) accountable for the decisions that affect IT outcomes. For additional discussion on managing exceptions see Weill, et.al.[20] and the IT Architecture Toolkit.[21]

An area prone to challenges with architectural standards is the specialized, vertical-market application, which is clearly the best fit with a critical operating area of the business but does not fit the architectural standards. When looking at all the trade-offs in situations like this, the compromise that best benefits the business relaxes architectural standards for a critical functional area. Ways to mitigate the impact associated with these difficult, sometimes costly compromise decisions include the development of an integration architecture to minimize the isolation of non-standardscompliant applications. The on-demand model for software-as-a-service (SaaS) is another area that has become a real-world option to help CIOs mitigate the impact of non-compliant applications. Applications delivered over the Internet as a service offering greatly reduce the impact on internal application architecture standards as the service provider manages the application and its related technology stack. Organizations can take advantage of application services that they would have a difficult time coping with if hosted internally. The challenge of information and data integration remains, and standards for application and data interoperability are evolving rapidly and continue to help mitigate this challenge.

Project portfolio management is where the actual implementation of enterprise architecture initiatives gets managed. The management process and toolset ties enterprise architecture to the outcomes of effective governance. Portfolio assessment, balance, project prioritization, and timing decisions processes are critical factors in successfully realizing the goals of the enterprise architecture. In the book, IT Portfolio Management Step-by- Step: Unlocking the Business Value of Technology, Maizlish and Handler outline eight essential stages to properly managing the IT portfolio.[22] The eight stages define the critical stage of balancing the portfolio against strategic objectives and other operating parameters. The portfolio must be the manifestation of the projects required to strategically align enterprise architecture investments to the requirements of the organization. It is a critical process step to correctly align architectural investment with strategic objectives, and the best practice CIO ensures that portfolio balancing occurs to properly balance architecture investments with tactical projects.

As in a financial portfolio where investments are balanced to specified levels of risk and reward and investments are grouped into specific sectors and asset allocations, the IT investment portfolio must balance immediate investments, such as critical business-facing projects and new application or e-business implementations, with long-term enabling investments in enterprise architecture and core infrastructure. Both long-term and short-term needs and outcomes need to be balanced if the enterprise is to obtain longterm benefits and payback from IT. It is through this balanced approach that the CIO establishes and maintains strategic IT momentum with regards to the correct architectural future-state required to meet business objectives.

An effective approach for the CIO to incorporate architecture investments into the IT portfolio is to align them with business initiatives whenever possible. This means tying architecture to current or upcoming business-facing projects expected to provide a business payback. It is important to establish deliverable value from architecture, which this close alignment facilitates. The business projects are highly leveraged by the common architecture and delivered more quickly once begun, and this is a key lever that demonstrates the value of architecture investment. Avoid trying to make architecture work as a stand-alone practice with projects that are not specifically tied to actual business-driven deliverables. This is one of the reasons many architecture efforts do not get off the ground— they are not aligned with specific investments and become viewed as abstract exercises. Best practice CIOs learn to see far enough into the future of IT requirements to anticipate these long-term needs and get the architectural work underway with sufficient lead-time to be in place when the business initiatives hit. This requires CIOs to be architectural planners—to think like architects and make every attempt to avoid a reaction mode when project requests come into their queues.

Starting from business strategy, the best practice CIO steers the organization through the process of defining current-state and future-state architectures, identifying the gap between them, and managing investment decisions through IT governance and portfolio management disciplines to achieve the desired outcomes. From the architecture-centric view, think of the relationship between IT governance, portfolio management, and enterprise architecture as the relationship between the concepts of what (technology) and how (processes). Enterprise architecture represents the what from an information technology standpoint, and it defines what IT and process capabilities the organization needs to realize its goals. (see Exhibit 2.4).

IT governance and portfolio management represent how IT works in terms of the processes that enable architectural goals to actually be achieved. Architecture is the blueprint, IT project portfolio management stewards the collection of IT investments that build the blueprint, IT governance ensures that people make the right decisions to correctly populate the portfolio, and the approval process inherently includes a review of architectural correctness and adherence. Without enterprise architecture, IT governance and portfolio management can result in projects with little or no strategic integration.

Enterprise architecture defines the criteria for the IT governance decisions. Additionally, enterprise architecture defines a large part of appropriate content for the IT project portfolio. At the same time, the enterprise cannot realize architectural goals without circular feedback loops that link back through decision making and IT portfolio management. Architecture, IT governance, and portfolio management constitute a cyclic dynamic, not a linear process, one-time event, or static plan. Not one of these practice disciplines can result in achievable designs or informed decision making in isolation. It is precisely the outcome of this process that the CIO must focus upon. The CIO attains a strategically aligned architecture via an effective IT governance process and an IT project portfolio that balances investments in enterprise architecture with other business-specific IT investments.

Organizational competencies are rapidly becoming increasingly important elements of competitive advantage as Wall Street learns the intangible value of information technology, integrated supply chains, and intellectual capital. The rise to prominence of chief learning officer and chief knowledge officer positions, the incorporation of e-learning and knowledge management into the enterprise, Six Sigma, and a host of other learning, knowledge, and process-focused initiatives and technologies validates and accelerates the importance of this trend (for more on managing intangible IT value, see Part 2 of Chapter 8).

Technology-driven organizations have a constant need to develop skills and understand which skills and competencies will be needed in the future. Because competency development is a long-term initiative, it becomes increasingly important to be able to forecast and predict what competencies will be most important in the future.

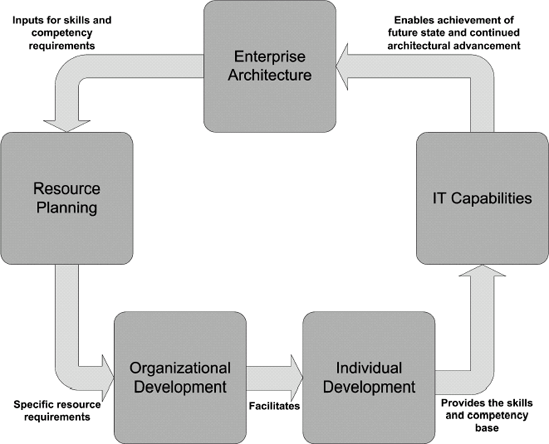

Enterprise architecture has an important contribution to make to the development of organizational competencies and the continued importance of the CIO role. We have already seen that enterprise architecture specifically plans the future-state of enterprise information and technology architectures and helps bridge the gap from the current-state. The blueprints created by EA provide a critical bridge between enterprise strategy and the technologies, information, and processes required to enable the strategy. These EA blueprints and plans also provide important inputs to the process of designing required future-states for competencies of the enterprise's managers and workforce.

The future vision enabled by enterprise architecture gives CIOs developmental roadmaps at both the individual and organizational levels. For the individual IT staff member, the EA future-state models for business architecture, information, and technology provide a clear path for aligning career and educational development plans. Career paths become more tangible when charting one's future within an organization, as does personal commitment. Individuals can see where they are going professionally and learn to focus their growth and personal development. The ability for an individual to assess one's own current-state skills and competencies to map professional development into the future becomes a very powerful planning and staff retention tool. In my experiences with direct career development planning with more than 100 IT colleagues, the ability for an IT professional to tangibly visualize and plan one's career development and navigate within the enterprise is one of the most important motivators and retention tools at the CIO's disposal.

Succession planning is facilitated as individuals conscientiously address future professional growth, professional transitions, and the information they need to successfully plan the successions. The basis for understanding future required competencies and mapping those back into individualized career development plans can be principally enabled by the outputs of enterprise architecture and IT strategic planning.

For the IT organization, enterprise architecture provides critical inputs for development planning. A future-state enterprise architecture vision requires new competencies in the business. Managers need to know what skills to recruit for, what types of learning and knowledge management programs to implement, and how to organize and architect the organization to become more competitive. The ability to innovate faster than the competition and ingrain this innovation throughout the workforce are increasingly critical competitive differentiators. EA provides the roadmaps for organizational, information, and technology future-states that facilitate organizational development (see Exhibit 2.5).

Human resource requirements planning and development is a key factor in the linkage between enterprise architecture and organizational development. A firm needs to understand its demand curve for skills and competencies based on an understanding of its architectural and IT portfolio requirements. It then becomes possible to accurately source for skills and services in the marketplace. Project labor utilization rates are a key indicator of efficiency and project profitability. As such, the ability to identify current and future need is an opportunity to directly manage costs and project output. EA blueprints combined with IT portfolio schedules are a direct link for identifying and forecasting skills and competencies throughout the organization. The CIO can only deliver through the people of the IT organization. The best architectural designs and the most expertly crafted IT governance and portfolio management processes won't make much contribution without execution, execution happens through people, and people execute through their skills and competencies. The best practice CIO encourages and fosters the contributions that a sound enterprise architecture program can make to the development of both individual staff members and the intellectual capital of the organization.

There is really no better way to tie together the implementation of the many practice principles discussed in this chapter than to describe the challenges and successes of an actual case study. In 2001 Golden Gate University (GGU), facing new competition in the face of revenue and profitability pressures, brought in a new senior management team to perform a turnaround to reposition the university in a new competitive marketplace for adult professional education. The new management team led significant change across academics, operations, technology, and financial capitalization. The turnaround plan called for a renewed focus on technology and a goal of ubiquitous 24/7 access to all information, transaction, and learning via a Web browser. From the standpoint of information technology, GGU was behind the technology curve with aging legacy systems, no IT architecture, static Web sites, and poor integration. The IT organization was configured in silos with little cooperation, and skills were not well aligned with modern technologies. The turnaround plan created pressures to deliver a new business strategy, create a new customer experience, and reduce costs of delivery throughout the enterprise. Essentially, the university articulated an e-business transformation, which required a complete overhaul of IT infrastructure, online applications, and educational offerings, an improved IT services delivery model, and new skills and organizational competencies throughout the university. A key constraint was that IT operating costs could not increase. In other words, we needed to transform IT but could not make it more expensive to run IT.

GGU's IT turnaround followed the approach illustrated by the Business/IT Strategy Realization Funnel. Beginning with the goals of an articulated business strategy, our fundamental approach led with enterprise architecture as the cornerstone of the effort. We anchored our effort around the concept of the architecture-centric view on IT and drove the development of processes, standards, IT governance, portfolio management, and organizational development from that basis. GGU focused on the alignment of the architecture with the stated business goals. We created a current-state view on the technology and a future-state model needed to realize the e-business vision. The gaps between the current-state and future-state architectures and the requirement to bring down IT costs were the drivers for all of the large IT investments and the balance of the project portfolio (see Chapters 4 and 6 for how such drivers can be incorporated into the enterprise financial systems). Over the subsequent five years, the university systematically executed on its e-business and architectural transformation.

Among other things, the efforts have resulted in a new IT technical and security infrastructure overhauled from the bottom up, an enterprise-wide database architecture, a Java Web-application tier, new ERP and CRM applications, and a common customer experience for all online applications, which consolidated 29 unique and nonintegrated online experiences down to one. All business transactions moved to the Web, eliminating the need to come to the campus, and online learning moved up dramatically as a percentage of revenue. Innovation capacity greatly improved as IT costs moved from a ratio of 90%/10% maintenance/innovation to approximately 60%/40%. The combination of a common architecture and project management and portfolio methods increased project capacity by a factor of 10 when compared to previous time frames. The IT organization was reorganized, major business process re-engineering efforts overhauled much of operations, and significant investments were made to support organization development from investments in skills training to management and leadership programs. The university was awarded the CIO 100 award in 2004 for its success in creating agility and transformation through IT and the Infoworld 100 in 2003 for innovation in its e-business initiatives.

Plainly stated, without the consistent commitment and IT governance leadership by the senior leadership team of the university, we would not have been successful in our approach to lead with architecture. Leading with architecture represents a disciplined approach to IT investments, and many influences conspire to knock the uncommitted CIO off the path. The roles of the university COO/CFO and president were critical to set the cultural and procedural standards regarding the central role of enterprise architecture. They believed in the benefits of enterprise architecture and were committed to drive the cultural changes and disciplined decision making to support clear IT governance and architectural leadership.

A statement the GGU president made at the beginning of a multi-year series of project investments in a new ERP infrastructure illustrates the importance of the senior leadership commitment. One of our challenges was to re-engineer business processes to break down departmental silos and realign processes horizontally across the enterprise. When the departmental managers were debating if the applications should conform and be customized to meet their business processes or if the university should adopt many of the best practices reflected in the new applications designs, the president addressed the group on behalf of the new enterprise architecture's role. "The uniqueness of our business processes is not what creates value for the university. In fact, the uniqueness of our business processes represents an Achilles heel. The value of the university comes from uniqueness and distinction in our teaching and learning practices." He further added that GGU's biggest hurdle was cultural, getting everyone to believe that the uniqueness of isolated business processes was not where the value resided. With that one statement he set the expectations: it was not going to be business as usual and not everyone was going to get their way. He set the expectation that processes were going to change to meet the new goals of the university and that the enterprise architecture was going to be more important than the parochial desires of individual departments.

IT governance is a series of trade-off decisions. Not everyone is going to be happy with the decisions, or even the process. It is critical that the most senior levels of leadership set the tone and expectations for how IT is to be governed. The CIO, as the senior management team's IT leader, is uniquely responsible for obtaining this alignment and support. The CIO can leverage the concept of the IT/Business Strategy Realization Funnel to put all the practices of EA, IT governance, portfolio management, and organizational development process alignment into context to gain enterprise-wide commitment to support these disciplines.

The ability to clearly map business objectives into the architectural futurestate was essential in aligning people to the approach. This was done with a high-level view on the future-state enterprise architecture and a roadmap showing how the current-state architecture would migrate into the new. The articulation of this plan was possible at a high level without producing detailed architectural designs into specific processes or technologies. The organization was not capable of producing low-level architectural models at that early stage, yet the architectural direction needed to be established and approved if we were to move ahead. The lesson is that it is important to have an early high-level vision of where the architecture needs to go, but the lower-level and detailed modeling of that architecture should take place over time, driven by business-facing initiatives. Once the high-level architectural direction was set, we were able to define the projects that would enable the future-state.

We realized the future-state architecture by aligning those architectural investments with the projects that would provide business payback. We did not pursue architectural initiatives in the abstract. The pursuit of the business-facing projects is what allowed us to pursue lower-level designs and architectural investment in those areas.

Another example of the approach to align architecture investment incrementally with specific, business-value investment areas is General Motors. Former GM CTO Tony Scott, another CIO 100 award-winner, said when discussing GM's approach to EA, "In fact, we're not going to try to map all of GM; we're going to do it in bite-size chunks. In all the architecture projects we've done so far, we've never gone top-to-bottom, left-to-right and mapped every piece of information at every level of detail. We've focused on those areas that we thought provided the highest value to GM."[23] Scott pursued the approach of aligning architecture work to business requirements analysis for current or near-term projects and pursued architectural advancement incrementally.

Best practice CIOs align their EA with the important revenue or cost and efficiency drivers because they want senior managers to work as EA champions and have it accepted by the business project owners. For this reason, GGU aligned all architecture projects to business initiatives as defined by deriving the elements of EA from the university's strategy and stated goals.

GGU adopted a portfolio management approach for managing all IT investments. Our maxim is that if it is not approved and in the portfolio, then we are not working on it. The portfolio approach has been instrumental in our ability to align IT investments with stated strategy and unitlevel goals and objectives. The steps to reach the desired architecture, which reflects the important business initiatives, drove the contents of the project portfolio. GGU leadership took it a step further by quantifying university business strategy into eight key areas. We then inventoried all business-unit-specific goals and objectives, including IT, and linked every project in the portfolio with a specific element of strategy or approved business unit goal. If we could not match a project request to either a specific strategy or a business-unit goal, we did not do the project. The result was a portfolio of IT investments that everyone in the university supported, both administration and academic organizations. This was a noteworthy milestone because broad alignment is often very difficult to achieve in higher education settings, and transparency via the IT portfolio was a key instrument.

GGU wisely took a focus on organizational development aligned around required organizational competencies. Within IT, we specifically mapped individuals' career development plans to the requirements of the futurestate architecture. As a result, we found that people became energized, goal-oriented, and self-starting about their next career development step.

Business departments aligned their organizational development efforts around their new processes, skills requirements, and ways of doing business. Management and leadership at every level must have a commitment to organizational development, but they also need a tangible guiding force like enterprise architecture to show the organization where it is heading with regards to processes, technologies, and the requisite skills and competencies.

A clear architecture improves decision making for the CIO and other people in the enterprise by providing a set of standards and quantifiable directions against which to base decisions. In a classic example from GGU, one department had selected an application they wanted to procure that was totally non-compliant with our architectural standards, and as a result, fell outside the skill set of the IT department to implement or manage. The department intensely lobbied for acceptance of the application, and the effort involved many of the university's senior managers. The vendor offered application-hosting services, thereby reducing much of the architectural compliance impact. But after due diligence investigations we found that the vendor was very new to hosting and had no track record. Because the vendor was a small company we felt the risk was too great should it prove inadequate as a hosting provider. The IT organization was not equipped to take the application in-house if circumstances required us to do so. The GGU governance process supported IT in making the unpopular decision not to pursue the project, despite the expressed disappointment of the sponsoring department. We made a good decision. We eventually found a better, architecturally compliant solution and avoided a potential mission-critical liability. The take-home lesson is to stick to a disciplined approach to architectural standards. Be careful about making exceptions, and don't make them when other options exist. When making exceptions, make sure they are for the right reasons, and make sure the business understands the trade-offs, risks, and future cost impacts.

Enterprise architecture and an IT project portfolio are powerful tools for facilitating communications and enterprise alignment. Both disciplines provide the stage for clear prioritization and transparency of IT investments. This benefit became especially important for GGU where a large part of the enterprise focuses on academic goals and outcomes rather the business goals of the administration. Enterprise alignment challenges are notoriously difficult in higher educations environments. Our IT project portfolio and IT governance process were critical in achieving transparency regarding the focus of IT investments and how those investments supported the stated goals and strategies of the university.

The work we did to align the IT function to the academic side of the university is a good example of this EA benefit. We created an informal IT group under the leadership of the vice-president of academic affairs, focused on academic leadership and the libraries. The work of this group was key in fostering the academic/business alignment with information technology. The group spent a lot of time reviewing the portfolio on a regular basis, educating everyone about the strategic rationale behind GGU's IT investments. Additionally, the group brought academic leadership fully into the IT governance processes for proposing and obtaining approval on IT projects, alleviating the perceptions that the academic side was left out of the processes. In time, it enabled a productive dialog and process about how IT could add the best value for the academic component of GGU's mission. Additionally, the academic side developed an understanding about what was required for creating and implementing joint IT and academic projects and their delivery responsibilities.

Use this list to rate the effectiveness of your own enterprise architecture, IT governance and project portfolio management, and IT organizational development practices:

It is the goal of every good CIO to align IT strategy to business strategy.

CIOs must optimize the interrelationships and integrate four of their most important tools—enterprise architecture, IT governance, project portfolio management, and IT organizational development—to align and execute the IT contribution to the realization of business strategy and bridge the gap between business strategy and the information and technology structure of the organization.

These tools and techniques revolve around three long-standing core concepts well known in the systems development disciplines—people (IT organization development), process (IT governance and portfolio management), and technology (enterprise architecture) have stood the test of time as the primary and necessary components of successful solutions. As technology has become more ubiquitous and as technologies continue to commoditize, emphasis has evolved toward the capabilities of people and processes as the focal areas to glean return on investment and competitive advantage from IT investments. Enterprise architecture enables people and process capabilities and aligns them with strategy.