Planning

11.0 INTRODUCTION

The most important responsibilities of a project manager are planning, integrating, and executing plans. Almost all projects, because of their relatively short duration and often prioritized control of resources, require formal, detailed planning. The integration of the planning activities is necessary because each functional unit may develop its own planning documentation with little regard for other functional units.

Planning, in general, can best be described as the function of selecting the enterprise objectives and establishing the policies, procedures, and programs necessary for achieving them. Planning in a project environment may be described as establishing a predetermined course of action within a forecasted environment. The project's requirements set the major milestones. If line managers cannot commit because the milestones are perceived as unrealistic, the project manager may have to develop alternatives, one of which may be to move the milestones. Upper-level management must become involved in the selection of alternatives.

The project manager is the key to successful project planning. It is desirable that the project manager be involved from project conception through execution. Project planning must be systematic, flexible enough to handle unique activities, disciplined through reviews and controls, and capable of accepting multifunctional inputs. Successful project managers realize that project planning is an iterative process and must be performed throughout the life of the project.

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

5.2 Define Scope

One of the objectives of project planning is to completely define all work required (possibly through the development of a documented project plan) so that it will be readily identifiable to each project participant. This is a necessity in a project environment because:

- If the task is well understood prior to being performed, much of the work can be preplanned.

- If the task is not understood, then during the actual task execution more knowledge is gained that, in turn, leads to changes in resource allocations, schedules, and priorities.

- The more uncertain the task, the greater the amount of information that must be processed in order to ensure effective performance.

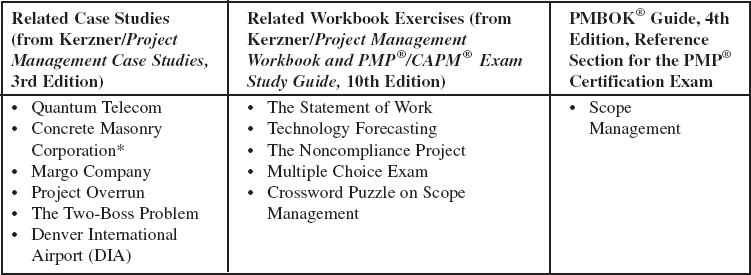

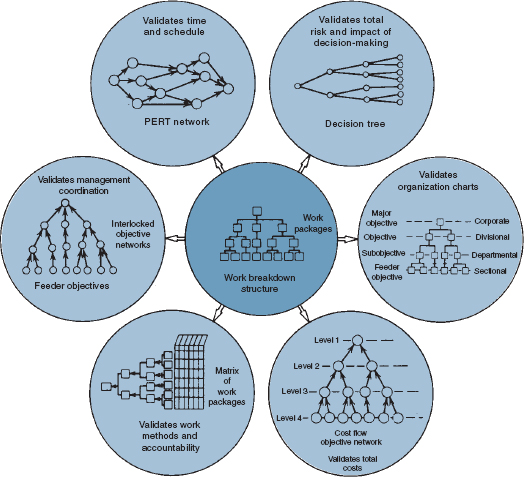

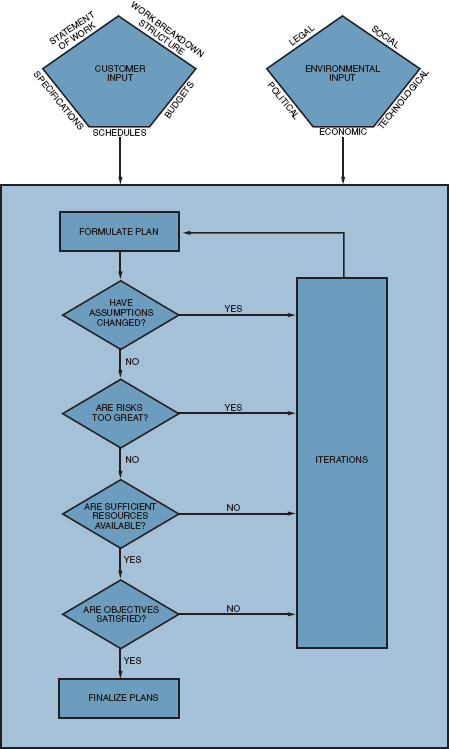

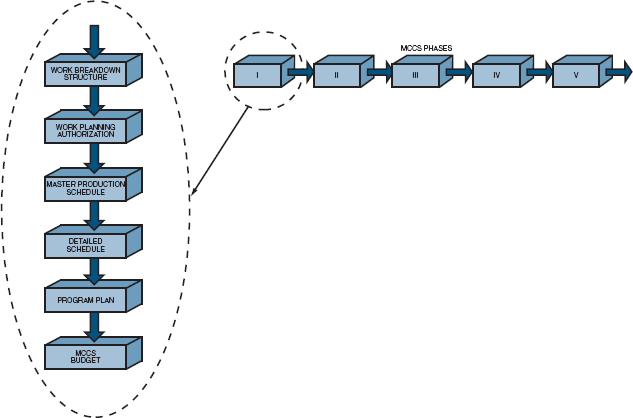

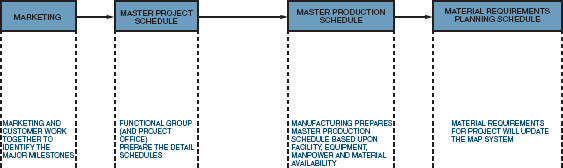

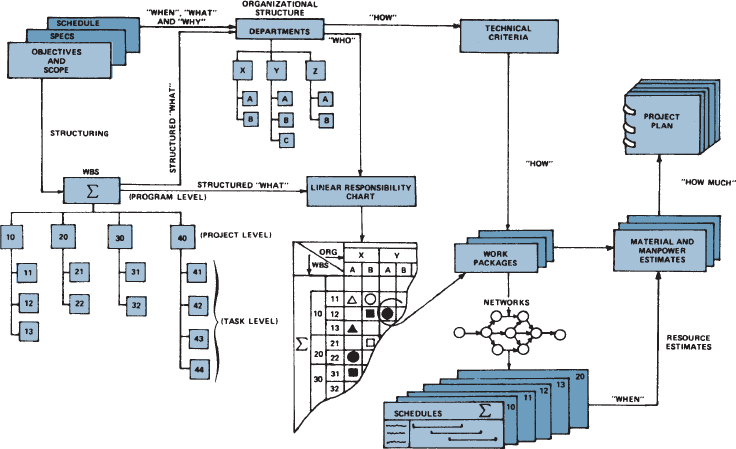

These considerations are important in a project environment because each project can be different from the others, requiring a variety of different resources, but having to be performed under time, cost, and performance constraints with little margin for error. Figure 11-1 identifies the type of project planning required to establish an effective monitoring and control system. The boxes at the top represent the planning activities, and the lower boxes identify the “tracking” or monitoring of the planned activities.

There are two proverbs that affect project planning:

- Failing to plan is planning to fail.

- The primary benefit of not planning is that failure will then come as a complete surprise rather than being preceded by periods of worry and depression.

Without proper planning, programs and projects can start off “behind the eight ball.” Consequences of poor planning include:

- Project initiation without defined requirements

- Wild enthusiasm

- Disillusionment

- Chaos

- Search for the guilty

- Punishment of the innocent

- Promotion of the nonparticipants

FIGURE 11-1. The project planning and control system.

There are four basic reasons for project planning:

- To eliminate or reduce uncertainty

- To improve efficiency of the operation

- To obtain a better understanding of the objectives

- To provide a basis for monitoring and controlling work

Planning is a continuous process of making entrepreneurial decisions with an eye to the future, and methodically organizing the effort needed to carry out these decisions. Furthermore, systematic planning allows an organization of set goals. The alternative to systematic planning is decision-making based on history. This generally results in reactive management leading to crisis management, conflict management, and fire fighting.

11.1 VALIDATING THE ASSUMPTIONS

Planning begins with an understanding of the assumptions. Quite often, the assumptions are made by marketing and sales personnel and then approved by senior management as part of the project selection and approval process. The expectations for the final results are based upon the assumptions made.

Why is it that, more often than not, the final results of a project do not satisfy senior management's expectations? At the beginning of a project, it is impossible to ensure that the benefits expected by senior management will be realized at project completion. While project length is a critical factor, the real culprit is changing assumptions.

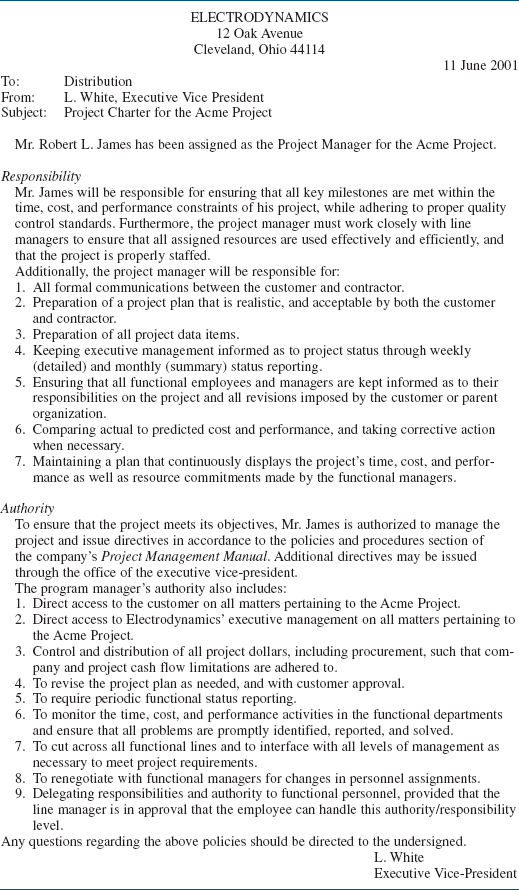

Assumptions must be documented at project initiation using the project charter as a possible means. Throughout the project, the project manager must revalidate and challenge the assumptions. Changing assumptions may mandate that the project be terminated or redirected toward a different set of objectives.

A project management plan is based upon the assumptions described in the project charter. But there are additional assumptions made by the team that are inputs to the project management plan.1 One of the primary reasons companies use a project charter is that project managers were most often brought on board well after the project selection process and approval process were completed. As a result, project managers were needed to know what assumptions were considered.

Enterprise Environmental Factors

These are assumptions about the external environmental conditions that can affect the success of the project, such as interest rates, market conditions, changing customer demands and requirements, changes in technology, and even government policies.

These are assumptions about present or future company assets that can impact the success of the project such as the capability of your enterprise project management methodology, the project management information system, forms, templates, guidelines, checklists, and the ability to capture and use lessons learned data and best practices.

11.2 GENERAL PLANNING

Planning is determining what needs to be done, by whom, and by when, in order to fulfill one's assigned responsibility. There are nine major components of the planning phase:

- Objective: a goal, target, or quota to be achieved by a certain time

- Program: the strategy to be followed and major actions to be taken in order to achieve or exceed objectives

- Schedule: a plan showing when individual or group activities or accomplishments will be started and/or completed

- Budget: planned expenditures required to achieve or exceed objectives

- Forecast: a projection of what will happen by a certain time

- Organization: design of the number and kinds of positions, along with corresponding duties and responsibilities, required to achieve or exceed objectives

- Policy: a general guide for decision-making and individual actions

- Procedure: a detailed method for carrying out a policy

- Standard: a level of individual or group performance defined as adequate or acceptable

An item that has become important in recent years is documenting assumptions that go into the objectives or the project/subsidiary plans. As projects progress, even for short-term projects, assumptions can change because of the economy, technological advances, or market conditions. These changes can invalidate original assumptions or require that new assumptions be made. These changes could also mandate that projects be canceled. Companies are now validating assumptions during gate review meetings. Project charters now contain sections for documenting assumptions.

Several of these factors require additional comment. Forecasting what will happen may not be easy, especially if predictions of environmental reactions are required. For example, planning is customarily defined as either strategic, tactical, or operational. Strategic planning is generally for five years or more, tactical can be for one to five years, and operational is the here and now of six months to one year. Although most projects are operational, they can be considered as strategic, especially if spin-offs or follow-up work is promising. Forecasting also requires an understanding of strengths and weaknesses as found in:

- The competitive situation

- Marketing

- Research and development

- Production

- Financing

- Personnel

- The management structure

If project planning is strictly operational, then these factors may be clearly definable. However, if strategic or long-range planning is necessary, then the future economic outlook can vary, say, from year to year, and replanning must be done at regular intervals because the goals and objectives can change. (The procedure for this can be seen in Figure 11-1.)

The last three factors, policies, procedures, and standards, can vary from project to project because of their uniqueness. Each project manager can establish project policies, provided that they fall within the broad limits set forth by top management.

Project policies must often conform closely to company policies, and are usually similar in nature from project to project. Procedures, on the other hand, can be drastically different from project to project, even if the same activity is performed. For example, the signing off of manufacturing plans may require different signatures on two selected projects even though the same end-item is being produced.

Planning varies at each level of the organization. At the individual level, planning is required so that cognitive simulation can be established before irrevocable actions are taken. At the working group or functional level, planning must include:

- Agreement on purpose

- Assignment and acceptance of individual responsibilities

- Coordination of work activities

- Increased commitment to group goals

- Lateral communications

At the organizational or project level, planning must include:

- Recognition and resolution of group conflict on goals

- Assignment and acceptance of group responsibilities

- Increased motivation and commitment to organizational goals

- Vertical and lateral communications

- Coordination of activities between groups

The logic of planning requires answers to several questions in order for the alternatives and constraints to be fully understood. A list of questions would include:

- Prepare environmental analysis

- Where are we?

- How and why did we get here?

- Set objectives

- Is this where we want to be?

- Where would we like to be? In a year? In five years?

- List alternative strategies

- Where will we go if we continue as before?

- Is that where we want to go?

- How could we get to where we want to go?

- List threats and opportunities

- What might prevent us from getting there?

- What might help us to get there?

- Prepare forecasts

- Where are we capable of going?

- What do we need to take us where we want to go?

- Select strategy portfolio

- What is the best course for us to take?

- What are the potential benefits?

- What are the risks?

- Prepare action programs

- What do we need to do?

- When do we need to do it?

- How will we do it?

- Who will do it?

- Monitor and control

- Are we on course? If not, why?

- What do we need to do to be on course?

- Can we do it?

One of the most difficult activities in the project environment is to keep the planning on target. These procedures can assist project managers during planning activities:

- Let functional managers do their own planning. Too often operators are operators, planners are planners, and never the twain shall meet.

- Establish goals before you plan. Otherwise short-term thinking takes over.

- Set goals for the planners. This will guard against the nonessentials and places your effort where there is payoff.

- Stay flexible. Use people-to-people contact, and stress fast response.

- Keep a balanced outlook. Don't overreact, and position yourself for an upturn.

- Welcome top-management participation. Top management has the capability to make or break a plan, and may well be the single most important variable.

- Beware of future spending plans. This may eliminate the tendency to underestimate.

- Test the assumptions behind the forecasts. This is necessary because professionals are generally too optimistic. Do not depend solely on one set of data.

- Don't focus on today's problems. Try to get away from crisis management and fire fighting.

- Reward those who dispel illusions. Avoid the Persian messenger syndrome (i.e., beheading the bearer of bad tidings). Reward the first to come forth with bad news.

11.3 LIFE-CYCLE PHASES

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

Chapter 2 Project Life Cycle and Organization

2.1 Characteristics of Project Phases

Project planning takes place at two levels. The first level is the corporate cultural approach; the second method is the individual's approach. The corporate cultural approach breaks the project down into life-cycle phases, such as those shown in Table 2-6. The life-cycle phase approach is not an attempt to put handcuffs on the project manager but to provide a methodology for uniformity in project planning. Many companies, including government agencies, prepare checklists of activities that should be considered in each phase. These checklists are for consistency in planning. The project manager can still exercise his own planning initiatives within each phase.

A second benefit of life-cycle phases is control. At the end of each phase there is a meeting of the project manager, sponsor, senior management, and even the customer, to assess the accomplishments of this life-cycle phase and to get approval for the next phase. These meetings are often called critical design reviews, “on-off ramps,” and “gates.” In some companies, these meetings are used to firm up budgets and schedules for the follow-on phases. In addition to monetary considerations, life-cycle phases can be used for manpower deployment and equipment/facility utilization. Some companies go so far as to prepare project management policy and procedure manuals where all information is subdivided according to life-cycle phasing. Life-cycle phase decision points eliminate the problem where project managers do not ask for phase funding, but rather ask for funds for the whole project before the true scope of the project is known. Several companies have even gone so far as to identify the types of decisions that can be made at each end-of-phase review meeting. They include:

- Proceed with the next phase based on an approved funding level

- Proceed to the next phase but with a new or modified set of objectives

- Postpone approval to proceed based on a need for additional information

- Terminate project

Consider a company that utilizes the following life-cycle phases:

- Conceptualization

- Feasibility

- Preliminary planning

- Detail planning

- Execution

- Testing and commissioning

The conceptualization phase includes brainstorming and common sense and involves two critical factors: (1) identify and define the problem, and (2) identify and define potential solutions.

In a brainstorming session, all ideas are recorded and none are discarded. The brainstorming session works best if there is no formal authority present and if it lasts thirty to sixty minutes. Sessions over sixty minutes will produce ideas that may resemble science fiction.

The feasibility study phase considers the technical aspects of the conceptual alternatives and provides a firmer basis on which to decide whether to undertake the project.

The purpose of the feasibility phase is to:

- Plan the project development and implementation activities.

- Estimate the probable elapsed time, staffing, and equipment requirements.

- Identify the probable costs and consequences of investing in the new project.

If practical, the feasibility study results should evaluate the alternative conceptual solutions along with associated benefits and costs.

The objective of this step is to provide management with the predictable results of implementing a specific project and to provide generalized project requirements. This, in the form of a feasibility study report, is used as the basis on which to decide whether to proceed with the costly requirements, development, and implementation phases.

User involvement during the feasibility study is critical. The user must supply much of the required effort and information, and, in addition, must be able to judge the impact of alternative approaches. Solutions must be operationally, technically, and economically feasible. Much of the economic evaluation must be substantiated by the user. Therefore, the primary user must be highly qualified and intimately familiar with the workings of the organization and should come from the line operation.

The feasibility study also deals with the technical aspects of the proposed project and requires the development of conceptual solutions. Considerable experience and technical expertise are required to gather the proper information, analyze it, and reach practical conclusions.

Improper technical or operating decisions made during this step may go undetected or unchallenged throughout the remainder of the process. In the worst case, such an error could result in the termination of a valid project—or the continuation of a project that is not economically or technically feasible.

In the feasibility study phase, it is necessary to define the project's basic approaches and its boundaries or scope. A typical feasibility study checklist might include:

- Summary level

- Evaluate alternatives

- Evaluate market potential

- Evaluate cost effectiveness

- Evaluate producibility

- Evaluate technical base

- Detail level

- Prepare initial project goals and objectives

- Prepare preliminary cost estimates and development plan

The end result of the feasibility study is a management decision on whether to terminate the project or to approve its next phase. Although management can stop the project at several later phases, the decision is especially critical at this point, because later phases require a major commitment of resources. All too often, management review committees approve the continuation of projects merely because termination at this point might cast doubt on the group's judgment in giving earlier approval.

The decision made at the end of the feasibility study should identify those projects that are to be terminated. Once a project is deemed feasible and is approved for development, it must be prioritized with previously approved projects waiting for development (given a limited availability of capital or other resources). As development gets under way, management is given a series of checkpoints to monitor the project's actual progress as compared to the plan.

The third life-cycle phase is either preliminary planning or “defining the requirements.” This is the phase where the effort is officially defined as a project. In this phase, we should consider the following:

- General scope of the work

- Objectives and related background

- Contractor's tasks

- Contractor end-item performance requirements

- Reference to related studies, documentation, and specifications

- Data items (documentation)

- Support equipment for contract end-item

- Customer-furnished property, facilities, equipment, and services

- Customer-furnished documentation

- Schedule of performance

- Exhibits, attachments, and appendices

These elements can be condensed into four core documents, as will be shown in Section 11.7. Also, it should be noted that the word “customer” can be an internal customer, such as the user group or your own executives.

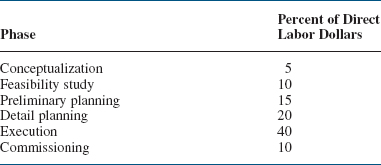

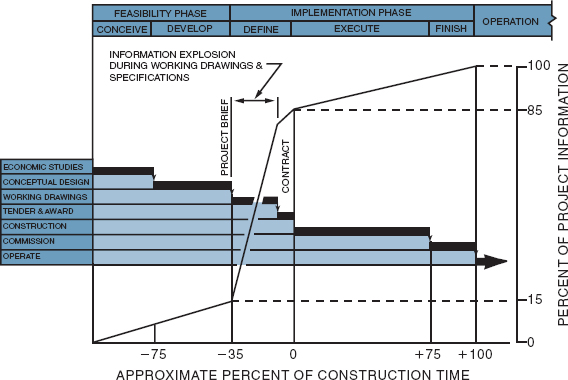

The table below shows the percentage of direct labor hours/dollars that are spent in each phase:

The interesting fact from this table is that as much as 50 percent of the direct labor hours and dollars can be spent before execution begins. The reason for this is simple: Quality must be planned for and designed in. Quality cannot be inspected into the project. Companies that spend less than these percentages usually find quality problems in execution.

11.4 PROPOSAL PREPARATION

There is always a question of what to do with a project manager between assignments. For companies that survive on competitive bidding, the assignment is clear: The project manager writes proposals for future work. This takes place during the feasibility study, when the company must decide whether to bid on the job. There are four ways in which proposal preparation can occur:

- Project manager prepares entire proposal. This occurs frequently in small companies. In large organizations, the project manager may not have access to all available data, some of which may be company proprietary, and it may not be in the best interest of the company to have the project manager spend all of his time doing this.

- Proposal manager prepares entire proposal. This can work as long as the project manager is allowed to review the proposal before delivery to the customer and feels committed to its direction.

- Project manager prepares proposal but is assisted by a proposal manager. This is common, but again places tremendous pressure on the project manager.

- Proposal manager prepares proposal but is assisted by a project manager. This is the preferred method. The proposal manager maintains maximum authority and control until such time as the proposal is sent to the customer, at which point the project manager takes charge. The project manager is on board right from the start, although his only effort may be preparing the technical volume of the proposal and perhaps part of the management volume.

11.5 KICKOFF MEETINGS

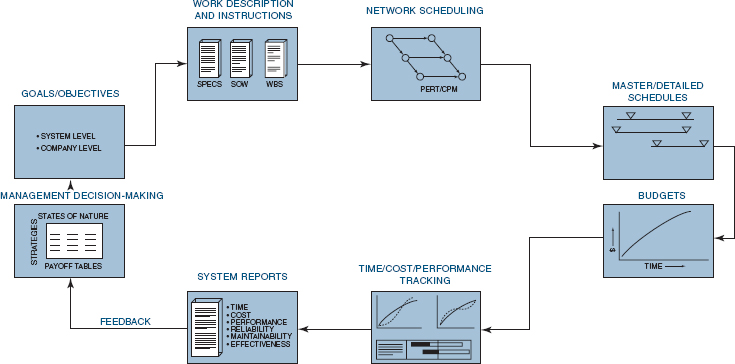

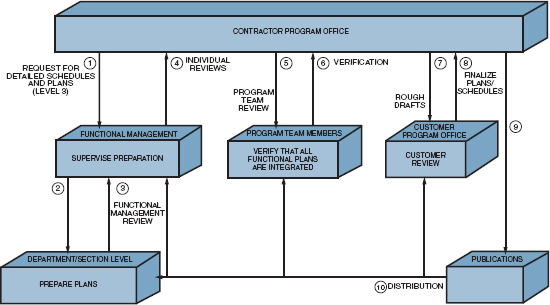

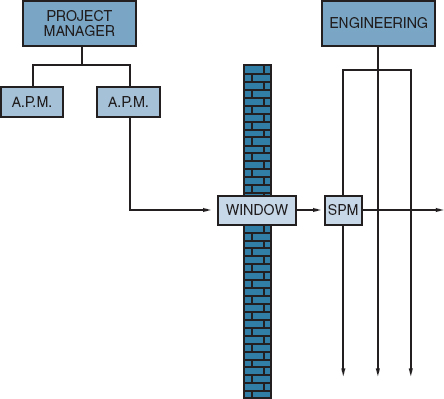

The typical launch of a project begins with a kickoff meeting involving the major players responsible for planning, including the project manager, assistant project managers for certain areas of knowledge, subject matter experts (SME), and functional leads. A typical sequence is shown in Figure 11-2.

There can be multiple kickoff meetings based upon the size, complexity, and time requirements for the project. The major players are usually authorized by their functional areas to make decisions concerning timing, costs, and resource requirements.

Some of the items discussed in the initial kickoff meeting include:

- Wage and salary administration, if applicable

- Letting the employees know that their boss will be informed as to how well or how poorly they perform

- Initial discussion of the scope of the project including both the technical objective and the business objective

- The definition of success on this project

- The assumptions and constraints as identified in the project charter

- The project's organizational chart (if known at that time)

- The participants' roles and responsibilities

For a small or short-term project, estimates on cost and duration may be established in the kickoff meeting. In this case, there may be little need to establish a cost estimating schedule. But where the estimating cycle is expected to take several weeks, and where inputs will be required from various organizations and/or disciplines, an essential tool is an estimating schedule. In this case, there may be a need for a prekickoff meeting simply to determine the estimates. The minimum key milestones in a cost estimating schedule are (1) a “kickoff” meeting; (2) a “review of ground rules” meeting; (3) “resources input and review” meeting; and (4) summary meetings and presentations. Descriptions of these meetings and their approximate places in the estimating cycle follow.2

The very first formal milestone in an estimate schedule is the estimate kickoff meeting. This is a meeting of all the individuals who are expected to have an input to the cost estimate. It usually includes individuals who are proficient in technical disciplines involved in the work to be estimated; business-oriented individuals who are aware of the financial factors to be considered in making the estimate; project-oriented individuals who are familiar with the project ground rules and constraints; and, finally, the cost estimator or cost estimating team. The estimating team may not include any of the team members responsible for execution of the project.

Sufficient time should be allowed in the kickoff meeting to describe all project ground rules, constraints, and assumptions; to hand out technical specifications, drawings, schedules, and work element descriptions and resource estimating forms; and to discuss these items and answer any questions that might arise. It is also an appropriate time to clarify estimating assignments among the various disciplines represented in the event that organizational charters are not clear as to who should support which part of the estimate. This kickoff meeting may be 6 weeks to 3 months prior to the estimate completion date to allow sufficient time for the overall estimating process. If the estimate is being made in response to a request for quotation or request for bid, copies of the request for quotation document will be distributed and its salient points discussed.

The Review of Ground Rules Meeting

Several days after the estimate kickoff meeting, when the participants have had the opportunity to study the material, a review of ground rules meeting should be conducted. In this meeting the estimate manager answers questions regarding the conduct of the cost estimate, assumptions, ground rules, and estimating assignments. If the members of the estimating team are experienced in developing resource estimates for their respective disciplines, very little discussion may be needed. However, if this is the first estimating cycle for one or more of the estimating team members, it may be necessary to provide these team members with additional information, guidance, and instruction on estimating tools and methods. If the individuals who will actually perform the work are doing the estimating (which is actually the best arrangement for getting a realistic estimate), more time and support may be needed than would experienced estimators.

The Resources Input and Review Meeting

Several weeks after the kickoff and review of ground rules meetings, each team member that has a resources (man-hour and/or materials) input is asked to present his or her input before the entire estimating team. Thus starts one of the most valuable parts of the estimating process: the interaction of team members to reduce duplications, overlaps, and omissions in resource data.

The most valuable aspect of a team estimate is the synergistic effect of team interaction. In any multidisciplinary activity, it is the synthesis of information and actions that produces wise decisions rather than the mere volume of data. In this review meeting the estimator of each discipline area has the opportunity to justify and explain the rationale for his estimates in view of his peers, an activity that tends to iron out inconsistencies, over-statements, and incompatibilities in resources estimates. Occasionally, inconsistencies, overlaps, duplications, and omissions will be so significant that a second input and review meeting will be required to collect and properly synthesize all inputs for an estimate.

Once the resources inputs have been collected, adjusted, and “priced,” the cost estimate is presented to the estimating team as a “dry run” for the final presentation to the company's management or to the requesting organization. This dry run can produce visibility into further inconsistencies or errors that have crept into the estimate during the process of consolidation and reconciliation. The final review with the requesting organization or with the company's management could also bring about some changes in the estimate due to last minute changes in ground rules or budget-imposed cost ceilings.

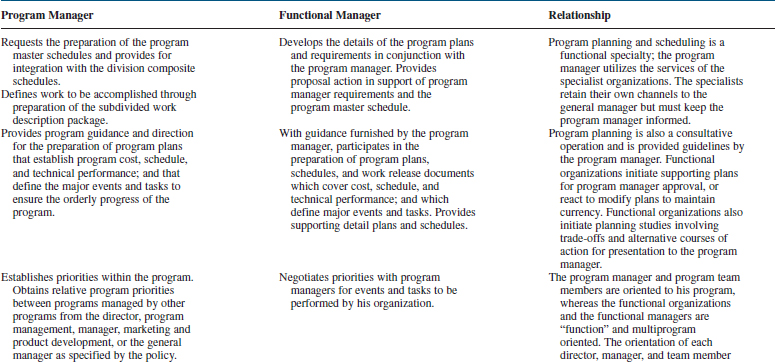

11.6 UNDERSTANDING PARTICIPANTS' ROLES

Companies that have histories of successful plans also have employees who fully understand their roles in the planning process. Good up-front planning may not eliminate the need for changes, but may reduce the number of changes required. The responsibilities of the major players are as follows:

- Project manager will define:

- Goals and objectives

- Major milestones

- Requirements

- Ground rules and assumptions

- Time, cost, and performance constraints

- Operating procedures

- Administrative policy

- Reporting requirements

- Line manager will define:

- Detailed task descriptions to implement objectives, requirements, and milestones

- Detailed schedules and manpower allocations to support budget and schedule

- Identification of areas of risk, uncertainty, and conflict

- Senior management (project sponsor) will:

- Act as the negotiator for disagreements between project and line management

- Provide clarification of critical issues

- Provide communication link with customer's senior management

Successful planning requires that project, line, and senior management are in agreement with the plan.

11.7 PROJECT PLANNING

Successful project management, whether in response to an in-house project or a customer request, must utilize effective planning techniques. The first step is understanding the project objectives. These goals may be to develop expertise in a given area, to become competitive, to modify an existing facility for later use, or simply to keep key personnel employed.

The objectives are generally not independent; they are all interrelated, both implicitly and explicitly. Many times it is not possible to satisfy all objectives. At this point, management must prioritize the objectives as to which are strategic and which are not. Typical problems with developing objectives include:

- Project objectives/goals are not agreeable to all parties.

- Project objectives are too rigid to accommodate changing priorities.

- Insufficient time exists to define objectives well.

- Objectives are not adequately quantified.

- Objectives are not documented well enough.

- Efforts of client and project personnel are not coordinated.

- Personnel turnover is high.

Once the objectives are clearly defined, four questions must be considered:

- What are the major elements of the work required to satisfy the objectives, and how are these elements interrelated?

- Which functional divisions will assume responsibility for accomplishment of these objectives and the major-element work requirements?

- Are the required corporate and organizational resources available?

- What are the information flow requirements for the project?

If the project is large and complex, then careful planning and analysis must be accomplished by both the direct- and indirect-labor-charging organizational units. The project organizational structure must be designed to fit the project; work plans and schedules must be established so that maximum allocation of resources can be made; resource costing and accounting systems must be developed; and a management information and reporting system must be established.

Effective total program planning cannot be accomplished unless all of the necessary information becomes available at project initiation. These information requirements are:

- The statement of work (SOW)

- The project specifications

- The milestone schedule

- The work breakdown structure (WBS)

The statement of work (SOW) is a narrative description of the work to be accomplished. It includes the objectives of the project, a brief description of the work, the funding constraint if one exists, and the specifications and schedule. The schedule is a “gross” schedule and includes such things as the:

- Start date

- End date

- Major milestones

- Written reports (data items)

Written reports should always be identified so that if functional input is required, the functional manager will assign an individual who has writing skills.

The last major item is the work breakdown structure. The WBS is the breaking down of the statement of work into smaller elements for better visibility and control. Each of these planning items is described in the following sections.

11.8 THE STATEMENT OF WORK

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

5.2.3 Scope Definition

5.2.3.1 Project Scope Statement

12.1.3.2 Contract Statement of Work

The PMBOK® Guide addresses four elements related to scope:

- Scope: Scope is the summation of all deliverables required as part of the project. This includes all products, services, and results.

- Project Scope: This is the work that must be completed to achieve the final scope of the project, namely the products, services, and end results. (Previously, in Section 2.7, we differentiated between project scope and product scope.)

- Scope Statement: This is a document that provides the basis for making future decisions such as scope changes. The intended use of the document is to make sure that all stakeholders have a common knowledge of the project scope. Included in this document are the objectives, description of the deliverables, end result or product, and justification for the project. The scope statement addresses seven questions: who, what, when, why, where, how, and how many. This document validates the project scope against the statement of work provided by the customer.

- Statement of Work: This is a narrative description of the end results to be provided under the contract. For the remainder of this section, we will focus our attention on the statement of work.

The statement of work (SOW) is a narrative description of the work required for the project. The complexity of the SOW is determined by the desires of top management, the customer, and/or the user groups. For projects internal to the company, the SOW is prepared by the project office with input from the user groups because the project office is usually composed of personnel with writing skills.

For projects external to the organization, as in competitive bidding, the contractor may have to prepare the SOW for the customer because the customer may not have people trained in SOW preparation. In this case, as before, the contractor would submit the SOW to the customer for approval. It is also quite common for the project manager to rewrite a customer's SOW so that the contractor's line managers can price out the effort.

In a competitive bidding environment, there are two SOWs—the SOW used in the proposal and a contract statement of work (CSOW). There might also be a proposal WBS and a contract work breakdown structure (CWBS). Special care must be taken by contract and negotiation teams to discover all discrepancies between the SOW/WBS and CSOW/CWBS, or additional costs may be incurred. A good (or winning) proposal is no guarantee that the customer or contractor understands the SOW. For large projects, fact-finding is usually required before final negotiations because it is essential that both the customer and the contractor understand and agree on the SOW, what work is required, what work is proposed, the factual basis for the costs, and other related elements. In addition, it is imperative that there be agreement between the final CSOW and CWBS.

SOW preparation is not as easy as it sounds. Consider the following:

- The SOW says that you are to conduct a minimum of fifteen tests to determine the material properties of a new substance. You price out twenty tests just to “play it safe.” At the end of the fifteenth test, the customer says that the results are inconclusive and that you must run another fifteen tests. The cost overrun is $40,000.

- The Navy gives you a contract in which the SOW states that the prototype must be tested in “water.” You drop the prototype into a swimming pool to test it. Unfortunately, the Navy's definition of “water” is the Atlantic Ocean, and it costs you $1 million to transport all of your test engineers and test equipment to the Atlantic Ocean.

- You receive a contract in which the SOW says that you must transport goods across the country using “aerated” boxcars. You select boxcars that have open tops so that air can flow in. During the trip, the train goes through an area of torrential rains, and the goods are ruined.

These three examples show that misinterpretations of the SOW can result in losses of hundreds of millions of dollars. Common causes of misinterpretation are:

- Mixing tasks, specifications, approvals, and special instructions

- Using imprecise language (“nearly,” “optimum,” “approximately,” etc.)

- No pattern, structure, or chronological order

- Wide variation in size of tasks

- Wide variation in how to describe details of the work

- Failing to get third-party review

Misinterpretations of the statement of work can and will occur no matter how careful everyone has been. The result is creeping scope, or, as one telecommunications company calls it, “creeping elegance.” The best way to control creeping scope is with a good definition of the requirements up front, if possible.

Today, both private industry and government agencies are developing manuals on SOW preparation. The following is adapted from a NASA publication on SOW preparation3:

- The project manager or his designees should review the documents that authorize the project and define its objectives, and also review contracts and studies leading to the present level of development. As a convenience, a bibliography of related studies should be prepared together with samples of any similar SOWs, and compliance specifications.

- A copy of the WBS should be obtained. At this point coordination between the CWBS elements and the SOW should commence. Each task element of the preliminary CWBS should be explained in the SOW, and related coding should be used.

- The project manager should establish a SOW preparation team consisting of personnel he deems appropriate from the program or project office who are experts in the technical areas involved, and representatives from procurement, financial management, fabrication, test, logistics, configuration management, operations, safety, reliability, and quality assurance, plus any other area that may be involved in the contemplated procurement.

- Before the team actually starts preparation of the SOW, the project manager should brief program management as to the structure of the preliminary CWBS and the nature of the contemplated SOW. This briefing is used as a baseline from which to proceed further.

- The project manager may assign identified tasks to team members and identify compliance specifications, design criteria, and other requirements documentation that must be included in the SOW and assign them to responsible personnel for preparation. Assigned team members will identify and obtain copies of specifications and technical requirements documents, engineering drawings, and results of preliminary and/or related studies that may apply to various elements of the proposed procurement.

- The project manager should prepare a detailed checklist showing the mandatory items and the selected optional items as they apply to the main body or the appendixes of the SOW.

- The project manager should emphasize the use of preferred parts lists; standard subsystem designs, both existing and under development; available hardware in inventory; off-the-shelf equipment; component qualification data; design criteria handbooks; and other technical information available to design engineers to prevent deviations from the best design practices.

- Cost estimates (manning requirements, material costs, software requirements, etc.) developed by the cost estimating specialists should be reviewed by SOW contributors. Such reviews will permit early trade-off consideration on the desirability of requirements that are not directly related to essential technical objectives.

- The project manager should establish schedules for submission of coordinated SOW fragments from each task team member. He must assure that these schedules are compatible with the schedule for the request for proposal (RFP) issuance. The statement of work should be prepared sufficiently early to permit full project coordination and to ensure that all project requirements are included. It should be completed in advance of RFP preparation.

SOW preparation manuals also contain guides for editors and writers4:

- Every SOW that exceeds two pages in length should have a table of contents conforming to the CWBS coding structure. There should rarely be items in the SOW that are not shown on the CWBS; however, it is not absolutely necessary to restrict items to those cited in the CWBS.

- Clear and precise task descriptions are essential. The SOW writer should realize that his or her efforts will have to be read and interpreted by persons of varied background (such as lawyers, buyers, engineers, cost estimators, accountants, and specialists in production, transportation, security, audit, quality, finance, and contract management). A good SOW states precisely the product or service desired. The clarity of the SOW will affect administration of the contract, since it defines the scope of work to be performed. Any work that falls outside that scope will involve new procurement with probable increased costs.

- The most important thing to keep in mind when writing a SOW is the most likely effect the written work will have upon the reader. Therefore, every effort must be made to avoid ambiguity. All obligations of the government should be carefully spelled out. If approval actions are to be provided by the government, set a time limit. If government-furnished equipment (GFE) and/or services, etc., are to be provided, state the nature, condition, and time of delivery, if feasible.

- Remember that any provision that takes control of the work away from the contractor, even temporarily, may result in relieving the contractor of responsibility.

- In specifying requirements, use active rather than passive terminology. Say that the contractor shall conduct a test rather than that a test should be conducted. In other words, when a firm requirement is intended, use the mandatory term “shall” rather than the permissive term “should.”

- Limit abbreviations to those in common usage. Provide a list of all pertinent abbreviations and acronyms at the beginning of the SOW. When using a term for the first time, spell it out and show the abbreviation or acronym in parentheses following the word or words.

- When it is important to define a division of responsibilities between the contractor, other agencies, etc., a separate section of the SOW (in an appropriate location) should be included and delineate such responsibilities.

- Include procedures. When immediate decisions cannot be made, it may be possible to include a procedure for making them (e.g., “as approved by the contracting officer,” or “the contractor shall submit a report each time a failure occurs”).

- Do not overspecify. Depending upon the nature of the work and the type of contract, the ideal situation may be to specify results required or end-items to be delivered and let the contractor propose his best method.

- Describe requirements in sufficient detail to assure clarity, not only for legal reasons, but for practical application. It is easy to overlook many details. It is equally easy to be repetitious. Beware of doing either. For every piece of deliverable hardware, for every report, for every immediate action, do not specify that something be done “as necessary.” Rather, specify whether the judgment is to be made by the contractor or by the government. Be aware that these types of contingent actions may have an impact on price as well as schedule. Where expensive services, such as technical liaison, are to be furnished, do not say “as required.” Provide a ceiling on the extent of such services, or work out a procedure (e.g., a level of effort, pool of man-hours) that will ensure adequate control.

- Avoid incorporating extraneous material and requirements. They may add unnecessary cost. Data requirements are common examples of problems in this area. Screen out unnecessary data requirements, and specify only what is essential and when. It is recommended that data requirements be specified separately in a data requirements appendix or equivalent.

- Do not repeat detailed requirements or specifications that are already spelled out in applicable documents. Instead, incorporate them by reference. If amplification, modification, or exceptions are required, make specific reference to the applicable portions and describe the change.

Some preparation documents also contain checklists for SOW preparation.5 A checklist is furnished below to provide considerations that SOW writers should keep in mind in preparing statements of work:

- Is the SOW (when used in conjunction with the preliminary CWBS) specific enough to permit a contractor to make a tabulation and summary of manpower and resources needed to accomplish each SOW task element?

- Are specific duties of the contractor stated so he will know what is required, and can the contracting officer's representative, who signs the acceptance report, tell whether the contractor has complied?

- Are all parts of the SOW so written that there is no question as to what the contractor is obligated to do, and when?

- When it is necessary to reference other documents, is the proper reference document described? Is it properly cited? Is all of it really pertinent to the task, or should only portions be referenced? Is it cross-referenced to the applicable SOW task element?

- Are any specifications or exhibits applicable in whole or in part? If so, are they properly cited and referenced to the appropriate SOW element?

- Are directions clearly distinguishable from general information?

- Is there a time-phased data requirement for each deliverable item? If elapsed time is used, does it specify calendar or work days?

- Are proper quantities shown?

- Have headings been checked for format and grammar? Are subheadings comparable? Is the text compatible with the title? Is a multidecimal or alphanumeric numbering system used in the SOW? Can it be cross-referenced with the CWBS?

- Have appropriate portions of procurement regulations been followed?

- Has extraneous material been eliminated?

- Can SOW task/contract line items and configuration item breakouts at lower levels be identified and defined in sufficient detail so they can be summarized to discrete third-level CWBS elements?

- Have all requirements for data been specified separately in a data requirements appendix or its equivalent? Have all extraneous data requirements been eliminated?

- Are security requirements adequately covered if required?

- Has its availability to contractors been specified?

Finally, there should be a management review of the SOW preparation interpretation6:

During development of the Statement of Work, the project manager should ensure adequacy of content by holding frequent reviews with project and functional specialists to determine that technical and data requirements specified do conform to the guidelines herein and adequately support the common system objective. The CWBS/SOW matrix should be used to analyze the SOW for completeness. After all comments and inputs have been incorporated, a final team review should be held to produce a draft SOW for review by functional and project managers. Specific problems should be resolved and changes made as appropriate. A final draft should then be prepared and reviewed with the program manager, contracting officer, or with higher management if the procurement is a major acquisition. The final review should include a briefing on the total RFP package. If other program offices or other Government agencies will be involved in the procurement, obtain their concurrence also.

11.9 PROJECT SPECIFICATIONS

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

5.2 Define Scope

12.1.3.2 Contract Statement of Work

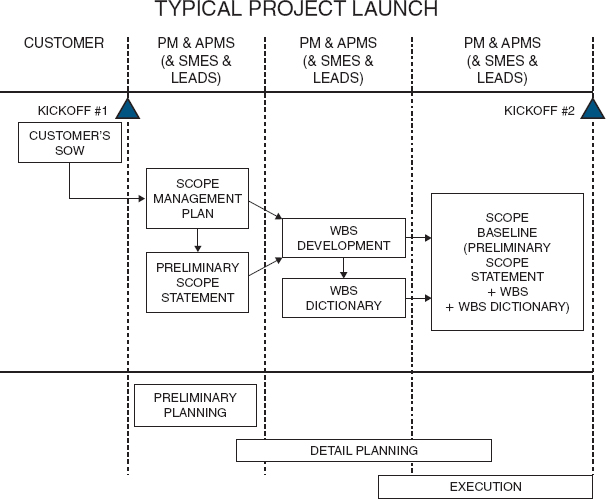

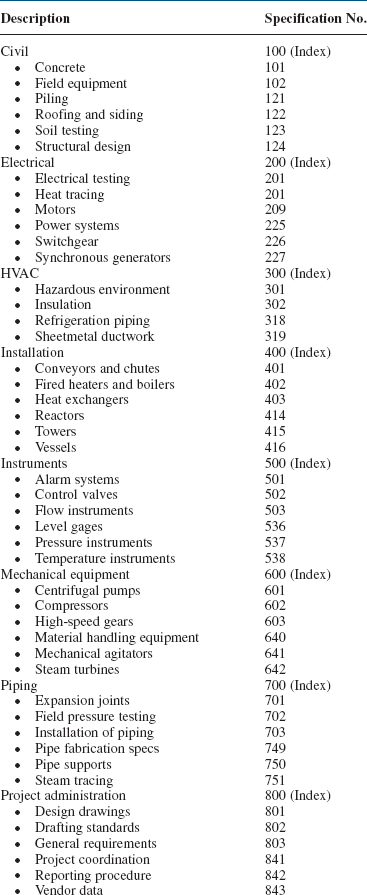

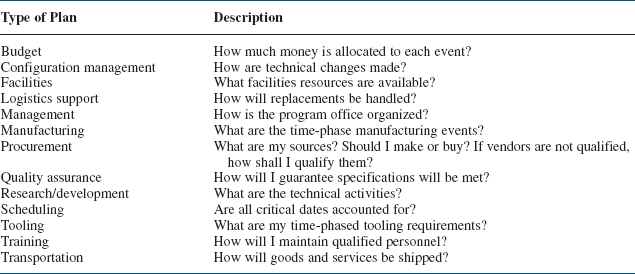

A specification list as shown in Table 11-1 is separately identified or called out as part of the statement of work. Specifications are used for man-hour, equipment, and material estimates. Small changes in a specification can cause large cost overruns.

Another reason for identifying the specifications is to make sure that there are no surprises for the customer downstream. The specifications should be the most current revision. It is not uncommon for a customer to hire outside agencies to evaluate the technical proposal and to make sure that the proper specifications are being used.

Specifications are, in fact, standards for pricing out a proposal. If specifications do not exist or are not necessary, then work standards should be included in the proposal. The work standards can also appear in the cost volume of the proposal. Labor justification backup sheets may or may not be included in the proposal, depending on RFP/RFQ (request for quotation) requirements.

Several years ago, a government agency queried contractors as to why some government programs were costing so much money. The main culprit turned out to be the specifications. Typical specifications contain twice as many pages as necessary, do not stress quality enough, are loaded with unnecessary designs and schematics, are difficult to read and update, and are obsolete before they are published. Streamlining existing specifications is a costly and time-consuming effort. The better alternative is to educate those people involved in specification preparation so that future specifications will be reasonably correct.

TABLE 11-1. SPECIFICATION FOR STATEMENT OF WORK

11.10 MILESTONE SCHEDULES

PMBOK® Guide 4th Edition

Chapter 6 Time Management

Project milestone schedules contain such information as:

- Project start date

- Project end date

- Other major milestones

- Data items (deliverables or reports)

Project start and end dates, if known, must be included. Other major milestones, such as review meetings, prototype available, procurement, testing, and so on, should also be identified. The last topic, data items, is often overlooked. There are two good reasons for preparing a separate schedule for data items. First, the separate schedule will indicate to line managers that personnel with writing skills may have to be assigned. Second, data items require direct-labor man-hours for writing, typing, editing, retyping, proofing, graphic arts, and reproduction. Many companies identify on the data item schedules the approximate number of pages per data item, and each data item is priced out at a cost per page, say $500/page. Pricing out data items separately often induces customers to require fewer reports.

The steps required to prepare a report, after the initial discovery work or collection of information, include:

- Organizing the report

- Writing

- Typing

- Editing

- Retyping

- Proofing

- Graphic arts

- Submittal for approvals

- Reproduction and distribution

Typically, 6–8 hours of work are required per page. At a burdened hourly rate of $80/hour, it is easy for the cost of documentation to become exorbitant.

11.11 WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

5.3 Create WBS

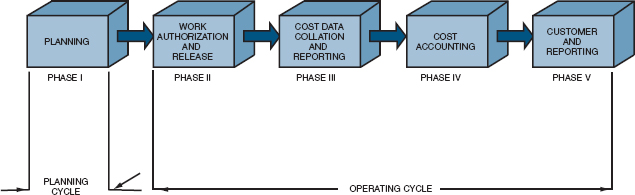

The successful accomplishment of both contract and corporate objectives requires a plan that defines all effort to be expended, assigns responsibility to a specially identified organizational element, and establishes schedules and budgets for the accomplishment of the work. The preparation of this plan is the responsibility of the program manager, who is assisted by the program team assigned in accordance with program management system directives. The detailed planning is also established in accordance with company budgeting policy before contractural efforts are initiated.

In planning a project, the project manager must structure the work into small elements that are:

- Manageable, in that specific authority and responsibility can be assigned

- Independent, or with minimum interfacing with and dependence on other ongoing elements

- Integratable so that the total package can be seen

- Measurable in terms of progress

The first major step in the planning process after project requirements definition is the development of the work breakdown structure (WBS). A WBS is a product-oriented family tree subdivision of the hardware, services, and data required to produce the end product. The WBS is structured in accordance with the way the work will be performed and reflects the way in which project costs and data will be summarized and eventually reported. Preparation of the WBS also considers other areas that require structured data, such as scheduling, configuration management, contract funding, and technical performance parameters. The WBS is the single most important element because it provides a common framework from which:

- The total program can be described as a summation of subdivided elements.

- Planning can be performed.

- Costs and budgets can be established.

- Time, cost, and performance can be tracked.

- Objectives can be linked to company resources in a logical manner.

- Schedules and status-reporting procedures can be established.

- Network construction and control planning can be initiated.

- The responsibility assignments for each element can be established.

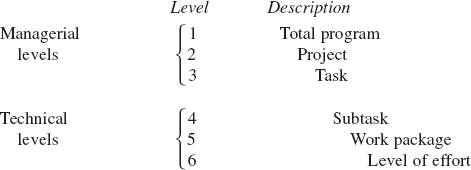

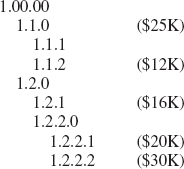

The work breakdown structure acts as a vehicle for breaking the work down into smaller elements, thus providing a greater probability that every major and minor activity will be accounted for. Although a variety of work breakdown structures exist, the most common is the six-level indented structure shown below:

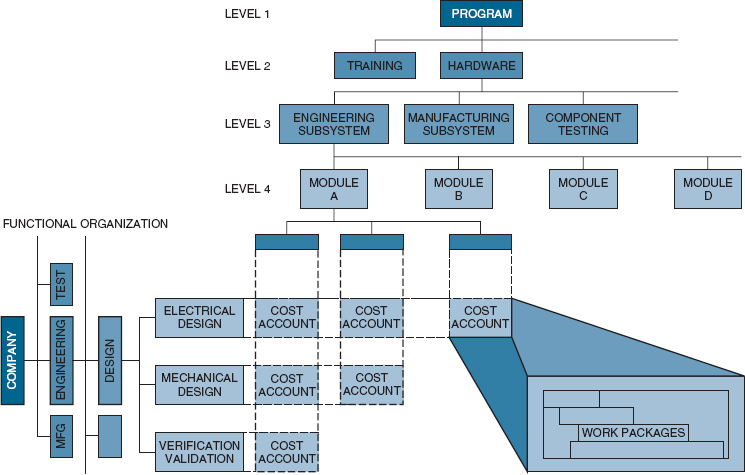

Level 1 is the total program and is composed of a set of projects. The summation of the activities and costs associated with each project must equal the total program. Each project, however, can be broken down into tasks, where the summation of all tasks equals the summation of all projects, which, in turn, comprises the total program. The reason for this subdivision of effort is simply ease of control. Program management therefore becomes synonymous with the integration of activities, and the project manager acts as the integrator, using the work breakdown structure as the common framework.

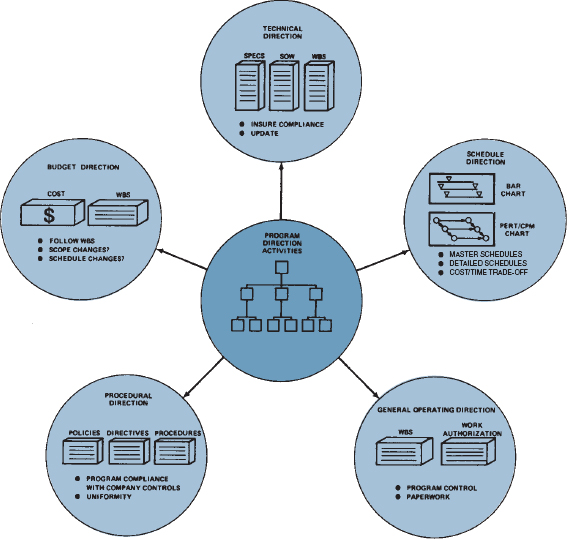

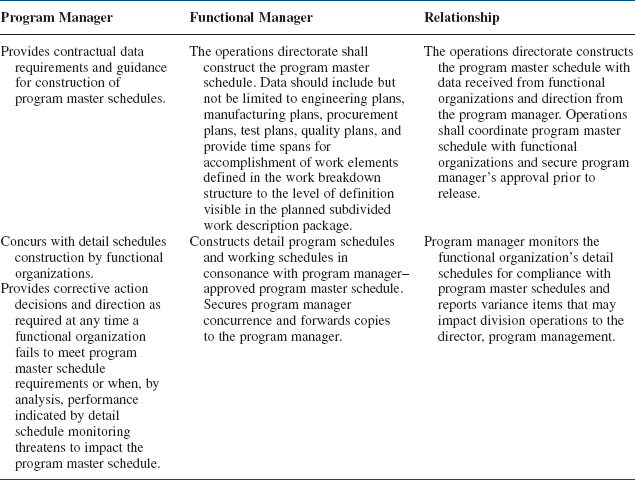

Careful consideration must be given to the design and development of the WBS. From Figure 11-3, the work breakdown structure can be used to provide the basis for:

- The responsibility matrix

- Network scheduling

- Costing

- Risk analysis

- Organizational structure

- Coordination of objectives

- Control (including contract administration)

The upper three levels of the WBS are normally specified by the customer (if part of an RFP/RFQ) as the summary levels for reporting purposes. The lower levels are generated by the contractor for in-house control. Each level serves a vital purpose: Level 1 is generally used for the authorization and release of all work, budgets are prepared at level 2, and schedules are prepared at level 3. Certain characteristics can now be generalized for these levels:

- The top three levels of the WBS reflect integrated efforts and should not be related to one specific department. Effort required by departments or sections should be defined in subtasks and work packages.

- The summation of all elements in one level must be the sum of all work in the next lower level.

- Each element of work should be assigned to one and only one level of effort. For example, the construction of the foundation of a house should be included in one project (or task), not extended over two or three. (At level 5, the work packages should be identifiable and homogeneous.)

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

Figure 5-6 Sample WBS

FIGURE 11-3. Work breakdown structure for objective control and evaluation. Source: Paul Mali, Managing by Objectives (New York: Wiley, 1972), p. 163. Copyright © 1972 by John Wiley & Sons. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

- The level at which the project is managed is generally called the work package level. Actually, the work package can exist at any level below level one.

- The WBS must be accompanied by a description of the scope of effort required, or else only those individuals who issue the WBS will have a complete understanding of what work has to be accomplished. It is common practice to reproduce the customer's statement of work as the description for the WBS.

- It is often the best policy for the project manager, regardless of his technical expertise, to allow all of the line managers to assess the risks in the SOW. After all, the line managers are usually the recognized experts in the organization.

Project managers normally manage at the top three levels of the WBS and prefer to provide status reports to management at these levels also. Some companies are trying to standardize reporting to management by requiring the top three levels of the WBS to be the same for every project, the only differences being in levels 4–6. For companies with a great deal of similarity among projects, this approach has merit. For most companies, however, the differences between projects make it almost impossible to standardize the top levels of the WBS.

The work package is the critical level for managing a work breakdown structure, as shown in Figure 11-4. However, it is possible that the actual management of the work packages is supervised and performed by the line managers with status reporting provided to the project manager at higher levels of the WBS.

Work packages are natural subdivisions of cost accounts and constitute the basic building blocks used by the contractor in planning, controlling, and measuring contract performance. A work package is simply a low-level task or job assignment. It describes the work to be accomplished by a specific performing organization or a group of cost centers and serves as a vehicle for monitoring and reporting progress of work. Documents that authorize and assign work to a performing organization are designated by various names throughout industry. “Work package” is the generic term used in the criteria to identify discrete tasks that have definable end results. Ideal work packages are 80 hours and 2–4 weeks. However, this may not be possible on large projects.

It is not necessary that work package documentation contain complete, stand-alone descriptions. Supplemental documentation may augment the work package descriptions. However, the work package descriptions must permit cost account managers and work package supervisors to understand and clearly distinguish one work package effort from another. In the review of work package documentation, it may be necessary to obtain explanations from personnel routinely involved in the work, rather than requiring the work package descriptions to be completely self-explanatory.

Short-term work packages may help evaluate accomplishments. Work packages should be natural subdivisions of effort planned according to the way the work will be done. However, when work packages are relatively short, little or no assessment of work-in-process is required and the evaluation of status is possible mainly on the basis of work package completions. The longer the work packages, the more difficult and subjective the work-in-process assessment becomes unless the packages are subdivided by objective indicators such as discrete milestones with preassigned budget values or completion percentages.

In setting up the work breakdown structure, tasks should:

- Have clearly defined start and end dates

- Be usable as a communications tool in which results can be compared with expectations

- Be estimated on a “total” time duration, not when the task must start or end

- Be structured so that a minimum of project office control and documentation (i.e., forms) is necessary

For large projects, planning will be time phased at the work package level of the WBS. The work package has the following characteristics:

- Represents units of work at the level where the work is performed

- Clearly distinguishes one work package from all others assigned to a single functional group

- Contains clearly defined start and end dates that are representative of physical accomplishment (This is accomplished after scheduling has been completed.)

- Specifies a budget in terms of dollars, man-hours, or other measurable units

- Limits the work to be performed to relatively short periods of time to minimize the work-in-process effort

Table 11-2 shows a simple work breakdown structure with the associated numbering system following the work breakdown. The first number represents the total program (in this case, it is represented by 01), the second number represents the project, and the third number identifies the task. Therefore, number 01-03-00 represents project 3 of program 01, whereas 01-03-02 represents task 2 of project 3. This type of numbering system is not standard; each company may have its own system, depending on how costs are to be controlled.

The preparation of the work breakdown structure is not easy. The WBS is a communications tool, providing detailed information to different levels of management. If it does not contain enough levels, then the integration of activities may prove difficult. If too many levels exist, then unproductive time will be made to have the same number of levels for all projects, tasks, and so on. Each major work element should be considered by itself. Remember, the WBS establishes the number of required networks for cost control.

For many programs, the work breakdown structure is established by the customer. If the contractor is required to develop a WBS, then certain guidelines must be considered including:

- The complexity and technical requirements of the program (i.e., the statement of work)

- The program cost

- The time span of the program

- The contractor's resource requirements

- The contractor's and customer's internal structure for management control and reporting

- The number of subcontracts

TABLE 11-2. WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE FOR NEW PLANT CONSTRUCTION AND START-UP

Applying these guidelines serves only to identify the complexity of the program. These data must then be subdivided and released, together with detailed information, to the different levels of the organization. The WBS should follow specified criteria because, although preparation of the WBS is performed by the program office, the actual work is performed by the doers, not the planners. Both the doers and the planners must be in agreement as to what is expected. A sample listing of criteria for developing a work breakdown structure is shown below:

- The WBS and work description should be easy to understand.

- All schedules should follow the WBS.

- No attempt should be made to subdivide work arbitrarily to the lowest possible level. The lowest level of work should not end up having a ridiculous cost in comparison to other efforts.

- Since scope of effort can change during a program, every effort should be made to maintain flexibility in the WBS.

- The WBS can act as a list of discrete and tangible milestones so that everyone will know when the milestones were achieved.

- The level of the WBS can reflect the “trust” you have in certain line groups.

- The WBS can be used to segregate recurring from nonrecurring costs.

- Most WBS elements (at the lowest control level) range from 0.5 to 2.5 percent of the total project budget.

11.12 WBS DECOMPOSITION PROBLEMS

There is a common misconception that WBS decomposition is an easy task to perform. In the development of the WBS, the top three levels or management levels are usually rollup levels. Preparing templates at these levels is becoming common practice. However, at levels 4–6 of the WBS, templates may not be appropriate. There are reasons for this.

- Breaking the work down to extremely small and detailed work packages may require the creation of hundreds or even thousands of cost accounts and charge numbers. This could increase the management, control, and reporting costs of these small packages to a point where the costs exceed the benefits. Although a typical work package may be 200–300 hours and approximately two weeks in duration, consider the impact on a large project, which may have more than one million direct labor hours.

- Breaking the work down to small work packages can provide accurate cost control if, and only if, the line managers can determine the costs at this level of detail. Line managers must be given the right to tell project managers that costs cannot be determined at the requested level of detail.

- The work breakdown structure is the basis for scheduling techniques such as the Arrow Diagramming Method and the Precedence Diagramming Method. At low levels of the WBS, the interdependencies between activities can become so complex that meaningful networks cannot be constructed.

One solution to the above problems is to create “hammock” activities, which encompass several activities where exact cost identification cannot or may not be accurately determined. Some projects identify a “hammock” activity called management support (or project office), which includes overall project management, data items, management reserve, and possibly procurement. The advantage of this type of hammock activity is that the charge numbers are under the direct control of the project manager.

There is a common misconception that the typical dimensions of a work package are approximately 80 hours and less than two weeks to a month. Although this may be true on small projects, this would necessitate millions of work packages on large jobs and this may be impractical, even if line managers could control work packages of this size.

From a cost control point of view, cost analysis down to the fifth level is advantageous. However, it should be noted that the cost required to prepare cost analysis data to each lower level may increase exponentially, especially if the customer requires data to be presented in a specified format that is not part of the company's standard operating procedures. The level-5 work packages are normally for in-house control only. Some companies bill customers separately for each level of cost reporting below level 3.

The WBS can be subdivided into subobjectives with finer divisions of effort as we go lower into the WBS. By defining subobjectives, we add greater understanding and, it is hoped, clarity of action for those individuals who will be required to complete the objectives. Whenever work is structured, understood, easily identifiable, and within the capabilities of the individuals, there will almost always exist a high degree of confidence that the objective can be reached.

Work breakdown structures can be used to structure work for reaching such objectives as lowering cost, reducing absenteeism, improving morale, and lowering scrap factors. The lowest subdivision now becomes an end-item or subobjective, not necessarily a work package as described here. However, since we are describing project management, for the remainder of the text we will consider the lowest level as the work package.

Once the WBS is established and the program is “kicked off,” it becomes a very costly procedure to either add or delete activities, or change levels of reporting because of cost control. Many companies do not give careful forethought to the importance of a properly developed WBS, and ultimately they risk cost control problems downstream. One important use of the WBS is that it serves as a cost control standard for any future activities that may follow on or may just be similar. One common mistake made by management is the combining of direct support activities with administrative activities. For example, the department manager for manufacturing engineering may be required to provide administrative support (possibly by attending team meetings) throughout the duration of the program. If the administrative support is spread out over each of the projects, a false picture is obtained as to the actual hours needed to accomplish each project in the program. If one of the projects should be canceled, then the support man-hours for the total program would be reduced when, in fact, the administrative and support functions may be constant, regardless of the number of projects and tasks.

Quite often work breakdown structures accompanying customer RFPs contain much more scope of effort, as specified by the statement of work, than the existing funding will support. This is done intentionally by the customer in hopes that a contractor may be willing to “buy in.” If the contractor's price exceeds the customer's funding limitations, then the scope of effort must be reduced by eliminating activities from the WBS. By developing a separate project for administrative and indirect support activities, the customer can easily modify his costs by eliminating the direct support activities of the canceled effort.

Before we go on, there should be a brief discussion of the usefulness and applicability of the WBS system. Many companies and industries have been successful in managing programs without the use of work breakdown structures, especially on repetitive-type programs. As was the case with the SOW, there are also preparation guides for the WBS7:

- Develop the WBS structure by subdividing the total effort into discrete and logical subelements. Usually a program subdivides into projects, major systems, major subsystems, and various lower levels until a manageable-size element level is reached. Wide variations may occur, depending upon the type of effort (e.g., major systems development, support services, etc.). Include more than one cost center and more than one contractor if this reflects the actual situation.

- Check the proposed WBS and the contemplated efforts for completeness, compatibility, and continuity.

- Determine that the WBS satisfies both functional (engineering/manufacturing/test) and program/project (hardware, services, etc.) requirements, including recurring and nonrecurring costs.

- Check to determine if the WBS provides for logical subdivision of all project work.

- Establish assignment of responsibilities for all identified effort to specific organizations.

- Check the proposed WBS against the reporting requirements of the organizations involved.

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

5.3.3.1 WBS

There are also checklists that can be used in the preparation of the WBS8:

- Develop a preliminary WBS to not lower than the top three levels for solicitation purposes (or lower if deemed necessary for some special reason).

- Assure that the contractor is required to extend the preliminary WBS in response to the solicitation, to identify and structure all contractor work to be compatible with his organization and management system.

- Following negotiations, the CWBS included in the contract should not normally extend lower than the third level.

- Assure that the negotiated CWBS structure is compatible with reporting requirements.

- Assure that the negotiated CWBS is compatible with the contractor's organization and management system.

- Review the CWBS elements to ensure correlation with:

- The specification tree

- Contract line items

- End-items of the contract

- Data items required

- Work statement tasks

- Configuration management requirements

- Define CWBS elements down to the level where such definitions are meaningful and necessary for management purposes (WBS dictionary).

- Specify reporting requirements for selected CWBS elements if variations from standard reporting requirements are desired.

- Assure that the CWBS covers measurable effort, level of effort, apportioned effort, and subcontracts, if applicable.

- Assure that the total costs at a particular level will equal the sum of the costs of the constituent elements at the next lower level.

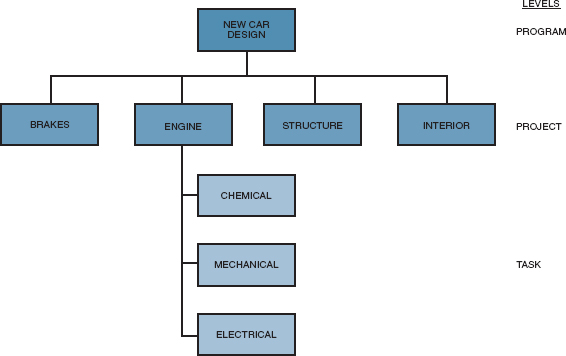

On simple projects, the WBS can be constructed as a “tree diagram” (see Figure 11-5) or according to the logic flow. In Figure 11-5, the tree diagram can follow the work or even the organizational structure of the company (i.e., division, department, section, unit). The second method is to create a logic flow (see Figure 12-21) and cluster certain elements to represent tasks and projects. In the tree method, lower-level functional units may be assigned to one, and only one, work element, whereas in the logic flow method the lower-level functional units may serve several WBS elements.

FIGURE 11-5. WBS tree diagram.

A tendency exists to develop guidelines, policies, and procedures for project management, but not for the development of the WBS. Some companies have been marginally successful in developing a “generic” methodology for levels 1, 2, and 3 of the WBS to use on all projects. The differences appear in levels 4, 5, and 6.

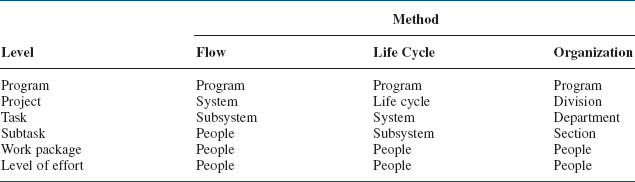

The table below shows the three most common methods for structuring the WBS:

The flow method breaks the work down into systems and major subsystems. This method is well suited for projects less than two years in length. For longer projects, we use the life-cycle method, which is similar to the flow method. The organization method is used for projects that may be repetitive or require very little integration between functional units.

11.13 ROLE OF THE EXECUTIVE IN PROJECT SELECTION

A prime responsibility of senior management (and possibly project sponsors) is the selection of projects. Most organizations have an established selection criteria, which can be subjective, objective, quantitative, qualitative, or simply a seat-of-the-pants guess. In any event, there should be a valid reason for selecting the project.

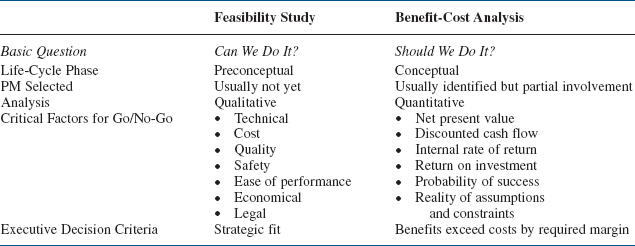

From a financial perspective, project selection is basically a two-part process. First, the organization will conduct a feasibility study to determine whether the project can be done. The second part is to perform a benefit-to-cost analysis to see whether the company should do it.

The purpose of the feasibility study is to validate that the project meets feasibility of cost, technological, safety, marketability, and ease of execution requirements. The company may use outside consultants or subject matter experts (SMEs) to assist in both feasibility studies and benefit-to-cost analyses. A project manager may not be assigned until after the feasibility study is completed.

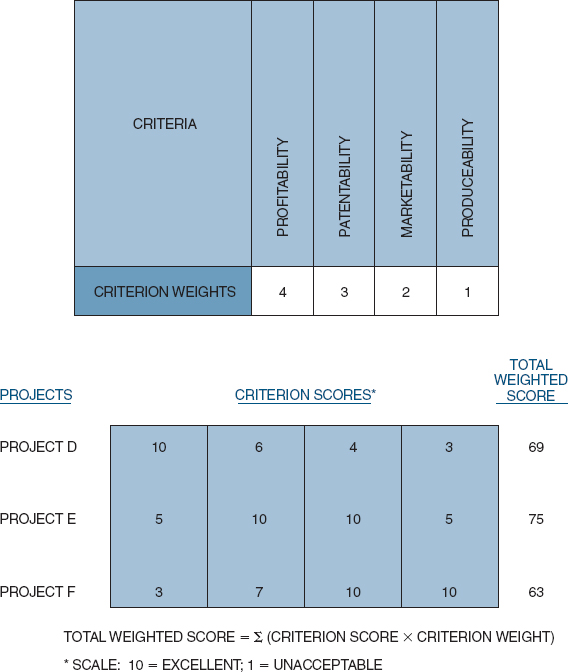

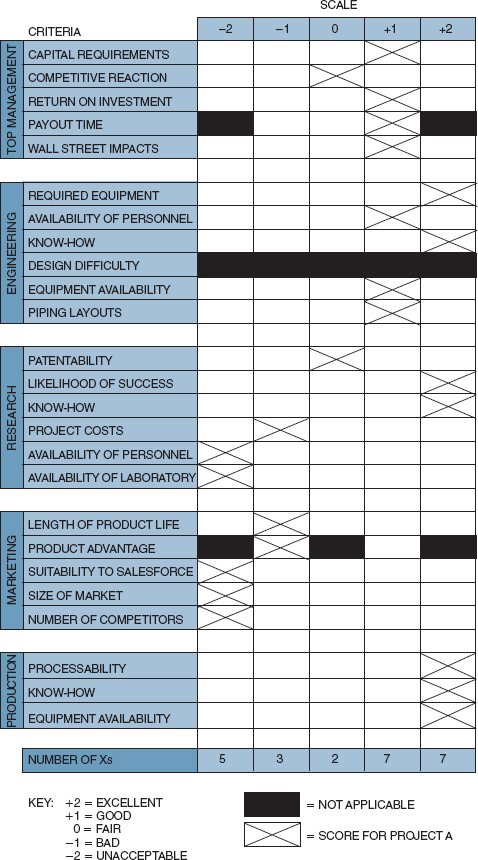

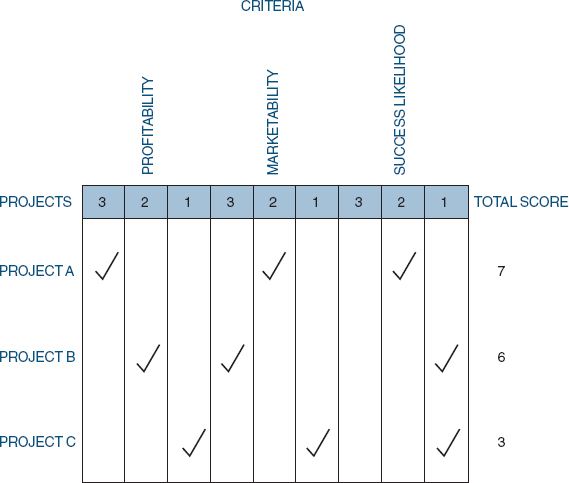

As part of the feasibility process during project selection, senior management often solicits input from SMEs and lower-level managers through rating models. The rating models normally identify the business and/or technical criteria against which the ratings will be made. Figure 11-6 shows a scaling model for a single project. Figure 11-7 shows a checklist rating system to evaluate three projects at once. Figure 11-8 shows a scoring model for multiple projects using weighted averages.

FIGURE 11-6. Illustration of a scaling model for one project, Project A. Source: William E. Souder, Project Selection and Economic Appraisal, p. 66.

If the project is deemed feasible and a good fit with the strategic plan, then the project is prioritized for development along with other projects. Once feasibility is determined, a benefit-to-cost analysis is performed to validate that the project will, if executed correctly, provide the required financial and nonfinancial benefits. Benefit-to-cost analyses require significantly more information to be scrutinized than is usually available during a feasibility study. This can be an expensive proposition.

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

5.2.2 Scope Definition

5.2.2.2 Product Analysis

Estimating benefits and costs in a timely manner is very difficult. Benefits are often defined as:

- Tangible benefits for which dollars may be reasonably quantified and measured.

- Intangible benefits that may be quantified in units other than dollars or may be identified and described subjectively.

FIGURE 11-7. Illustration of a checklist for three projects. Source: William Souder, Project Selection and Economic Appraisal, p. 68.

FIGURE 11-8. Illustration of a scoring model. Source: William Souder, Project Selection and Economic Appraisal, p. 69.

Costs are significantly more difficult to quantify. The minimum costs that must be determined are those that specifically are used for comparison to the benefits. These include:

- The current operating costs or the cost of operating in today's circumstances.

- Future period costs that are expected and can be planned for.

- Intangible costs that may be difficult to quantify. These costs are often omitted if quantification would contribute little to the decision-making process.

TABLE 11-3. FEASIBILITY STUDY AND BENEFIT-COST ANALYSIS

There must be careful documentation of all known constraints and assumptions that were made in developing the costs and the benefits. Unrealistic or unrecognized assumptions are often the cause of unrealistic benefits. The go or no-go decision to continue with a project could very well rest upon the validity of the assumptions.

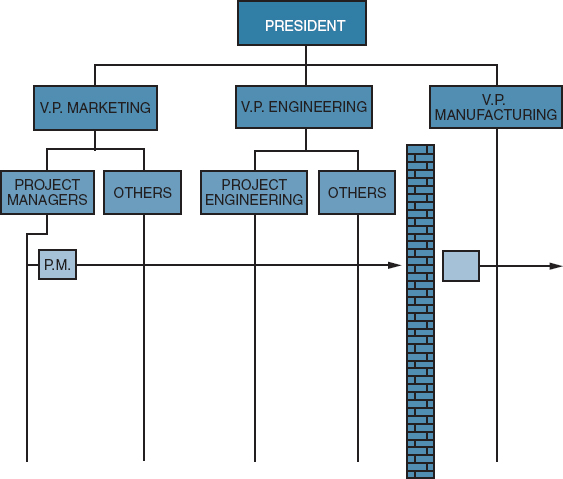

Table 11-3 shows the major differences between feasibility studies and benefit-to-cost analyses.