Chapter 4. Success Criteria Breed Success[4]

Note

I’ve worked with some government agencies whose project funding is made available based on a state budgeting cycle. The project schedule is always presented as an imposed constraint: the project must be done by the end of the budget cycle. But people in these agencies tell me that if they don’t complete the project by that time, they nearly always get more money and time to finish the project in the next budget cycle. So the schedule really isn’t a constraint at all, just a desirable target date.

"Begin with the end in mind" is Habit 2 from Stephen Covey’s The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People (Covey 1989). In Covey’s words, "To begin with the end in mind means to start with a clear understanding of your destination. It means to know where you’re going so that you better understand where you are now and so the steps you take are always in the right direction." At the beginning of every project, the stakeholders need to reach a common understanding of how they will determine whether this project is successful.

Consultant Tim Lister defines success as "meeting the set of all requirements and constraints held as expectations by key stakeholders." If you don’t know early on how you’re going to measure your project’s business success, you’re headed for trouble. Defining explicit success criteria during the project’s inception keeps stakeholders focused on shared objectives and establishes targets for evaluating progress. For initiatives that involve multiple subprojects, success criteria help align all subprojects with the big picture. Ill-defined, unrealistic, or poorly communicated success criteria can lead to disappointing business outcomes. Vague objectives such as "world class" or "killer app" are meaningless unless you can measure whether you’ve achieved them.

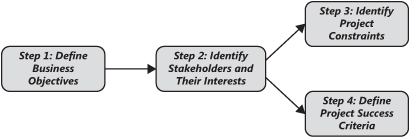

To help you determine where your project is heading, this chapter describes the four-step process for defining project success criteria shown in Figure 4-1. The deliverables from this chapter will help you make the myriad decisions that pop up during the life of a project.

The project charter template presented in Chapter 7, contains categories to store the information you’ll generate from the practices described in this chapter.

Business goals answer the question "Why do we want to tackle this project?" You can transform each goal into specific, attainable, verifiable, and prioritized business objectives to help you assess whether you’ve achieved the goal. Express business goals and objectives in terms of measurable business, political, or perhaps even social value. For example, a goal might be to "Demonstrate competitive advantage with distinguishing features and technologies." A corresponding business objective might state that specific features must be operational by a particular date. Another objective might require the team to demonstrate by a specific date that the planned technologies are sufficiently robust for use in your product (provided you can define what "robust" means).

A project that satisfies its requirements specification and ships on schedule and on budget is good. A product that achieves its intended business objectives is much better. Well-crafted business objectives articulate the bottom-line outcomes the product will deliver for both internal and external stakeholders. They include the expected outcome, the time frame for achieving the objective, and how you will measure successful achievement (Wysocki and McGary 2003). Be aware, some project participants might feel uncomfortable stating measurable business objectives. It’s a small step from "measurability" to "accountability."

Business objectives typically address:

What the product[5] must be and do, including essential or distinguishing functions it will perform and how well it will perform them.

Economic constraints, including development costs, cost of materials, and time to market.

The product’s operational and temporal context, such as technologies required for compatibility in the target environment, backward compatibility, and future extensibility.

Try to write business objectives that are SMART: Specific (not vague), Measurable (not qualitative), Attainable (not impossible), Relevant (not unimportant), and Time-based (not open-ended). Table 4-1 illustrates some simple business objective statements in both financial and nonfinancial categories.

Table 4-1. Examples of Financial and Nonfinancial Business Objectives

Financial | Nonfinancial |

|---|---|

Capture a market share of X% within Y months. | Achieve a customer satisfaction measure of at least X within Y months of release. |

Increase market share in region X by Y% in Z months. | Process at least X transactions per day with at least Y% accuracy. |

Reach a sales volume of X units or revenue of $Y within Z months. | Achieve X time to market that provides clear business advantages. |

Achieve X% profit or return on investment within Y months. | Develop a robust platform for a family of related products. |

Achieve positive cash flow on this product within Y months. | Develop specific core technology competencies in the organization, with competency measured in some way. |

Save $X per year by replacing a high-maintenance legacy system. | Be rated as the top product for reliability in published product reviews by a specified date. |

Keep unit materials cost below X dollars per unit over the expected Y-year lifetime of the product. | Maintain staff turnover below X% through the end of the project. |

Reduce support costs by X% within Y months. | Comply with a specific set of federal and state regulations. |

Receive no more than X service calls per unit and Y warranty calls per unit within Z months after shipping. | Reduce turnaround time to X hours on Y% of customer support calls. |

Record your business goals and objectives in a high-level strategic guiding document for the project. Such documents include a project charter (see Chapter 7), vision and scope document (Wiegers 2003), project datasheet, business case, or marketing requirements document. Some project management plan templates include a section on management objectives and priorities, which could contain your business objectives. A sample software project management plan template is provided on the Web site that accompanies this book. This template includes slots in which to store much of the information you’ll develop if you complete the worksheets in this book. Other information might go into other project guiding documents, such as a quality assurance plan that contains product release criteria.

As the team gets into design and implementation, they might discover certain business objectives to be unattainable. The cost of materials might be higher than planned or perhaps cutting-edge technologies don’t work as expected. Business realities also can change, along with evolving marketplace demands or reduced profit forecasts. Under such circumstances, you’ll need to modify your business objectives and reassess to see whether the project is still worth pursuing.

One telecommunications project had an objective to build a replacement interface unit for an existing product at a specified maximum unit cost and with a defined reusability goal. A review of the proposed architecture revealed that the product would exceed the unit cost and couldn’t meet the reusability goal. Management revisited the business case and concluded that the unit cost was still low enough to justify development. They revised the profit forecasts, dropped the reusability goal, and forged ahead. The key stakeholders redefined "success" to match business and technical realities.

[4] This article was originally published in The Rational Edge, February 2002. It is reprinted here, with modifications, with permission from IBM.

[5] I’ll use the terms product, application, and system to refer to whatever sort of software or software-containing deliverable your team is producing. These practices apply equally well to developing commercial software products, embedded systems, information systems, Web sites, and so on.