CHAPTER OVERVIEW

Learners must integrate content that enters working memory from the training environment into related knowledge structures previously stored in long-term memory to build a new mental model. For this integration to occur, these knowledge structures must transfer from long-term memory into working memory. This process is called activation of prior knowledge. Activation of relevant prior knowledge is an essential instructional event that must occur early in instruction.

In some situations, learners lack relevant prior knowledge. In these cases a high-level overview of the lesson content improves learning by providing a structure on which to hang new content.

Some attempts to gain learner attention and interest by adding extraneous dramatic visuals or stories actually depress learning because they activate irrelevant prior knowledge. In this chapter we present research, psychological rationale, and examples to support the following guidelines:

Use concrete graphics that serve as visual analogies as comparative advance organizers

Use visual summaries of lesson content as expository advance organizers

Avoid starting a lesson with a dramatic but extraneous visual that will activate inappropriate prior knowledge

The well-known learning psychologist Robert Gagne (1985) proposed several key events of learning. Event number three is activate prior knowledge. Recent research continues to point to the important role of activated prior knowledge as a prerequisite to learning. As described in Chapter Three, learning requires the integration of new lesson content with prior knowledge already stored in long-term memory. This integration process occurs in working memory, which is where learning happens. Therefore, relevant prior knowledge must be activated or retrieved from long-term memory to make it available in working memory. And it needs to be in working memory before the meat of the lesson is delivered.

In some situations learners will have relevant prior knowledge stored in longterm memory as a result of their job experience or previous learning. For these learners, schedule some introductory activity that will engage or activate that knowledge. However, in other circumstances your learners will have minimal prior knowledge relevant to the new knowledge and skills of the lesson. In these situations you need to build a knowledge base appropriate to the new lesson content. In either case you need to avoid introductory activities or content that activate prior knowledge that is not related to the instructional goal. Research we will discuss demonstrates the damaging effects of irrelevant visuals resulting from activation of inappropriate prior knowledge.

Clark (2003) has recently summarized a variety of instructional methods that are effective because they either activate or build prior knowledge. These include starting a lesson with a group discussion of a relevant problem, answering questions prior to learning new content, and designing an advance organizer. Since we are discussing ways graphics can be used to activate or build relevant prior knowledge, we will focus on the use of advance organizers that incorporate visuals.

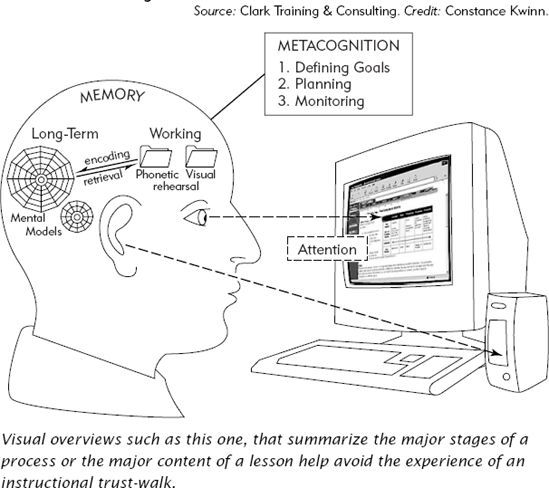

If you have ever tried a blindfolded trust walk, you know how unsettling it feels to be moving but not know where you are going! We can avoid instructional trust walks by using advance organizers. Advance organizers were defined by Ausubel in 1968 as instructional presentations appearing early in a lesson that "provide ideational scaffolding for the stable incorporation and retention of more detailed and differentiated material that follows" (p. 148). In everyday language, the advance organizer presents a high-level view of the key ideas to be presented in the lesson. For example, in Chapter Three we provided an overview of human psychological learning processes using the graphic in Figure 5.1.

There are two types of organizers you can use, depending on the prior knowledge of your learners: comparative or expository. The comparative organizer is most appropriate when your learners have relevant prior knowledge in longterm memory that should be activated. The expository organizer is most appropriate when your learners lack relevant prior knowledge. These learners need a knowledge base to help them assimilate the detailed content in the lesson.

For learners who do have prior knowledge related to your lesson content, use a comparative organizer. An effective comparative organizer incorporates information familiar to the learner and links that familiar information to new lesson content. In this way the comparative organizer serves as an analogy that links new content to existing prior knowledge. For example, Ausubel provided students with a brief text comparison of the relationships between Christianity and Buddhism prior to a lengthy reading on Buddhism. Students who read the comparison recalled more of the content about Buddhism than students who read an unrelated text (Ausubel and Youssef, 1963).

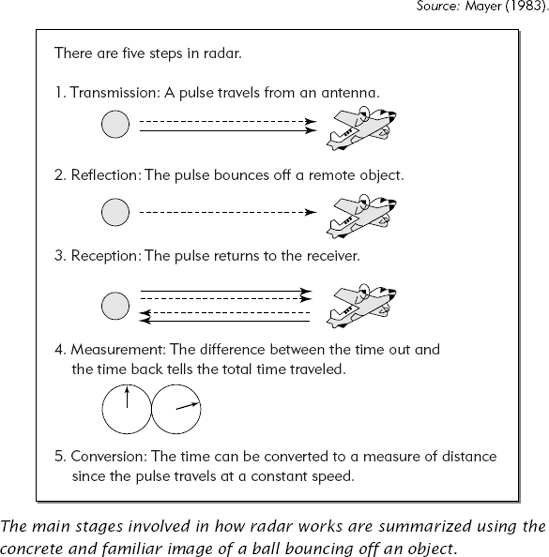

To be effective, a good organizer should be concrete. And that is where a relevant visual can help. To help learners recall and apply basic principles of how radar works, Mayer started the lesson with the diagram shown in Figure 5.2. Note that the diagram provides a high-level text and visual summary of the principle of radar using concrete familiar imagery. The image and text draw upon learners' prior familiarity with how a ball bounces off an object. In research that compared learning of groups that studied the radar lesson with and without the diagram, the recall and application scores of the diagram group were much higher (Mayer, 1983).

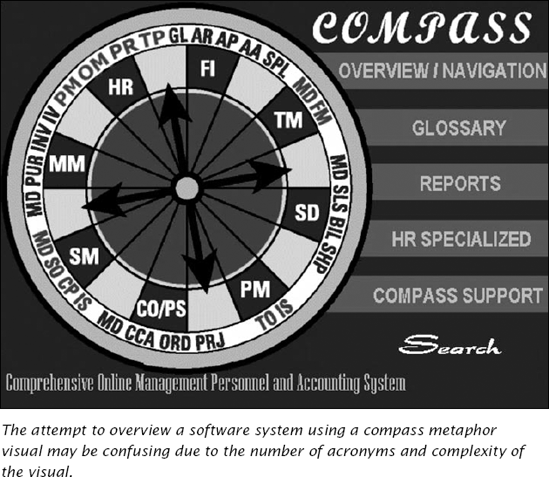

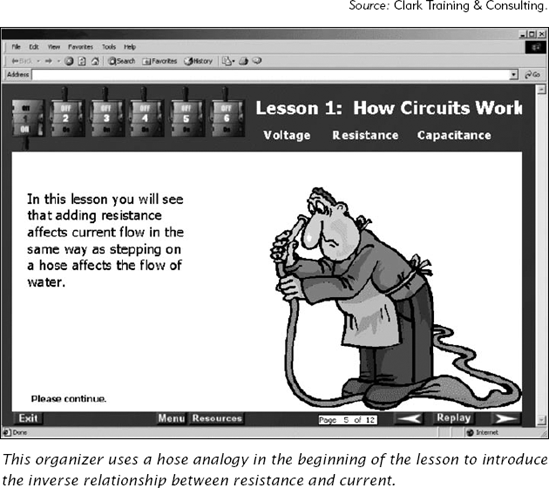

The success of the comparative organizer will depend on the extent to which learners make a good connection between the familiar information such as the ball in the radar lesson to the important new content in the lesson. Kloster and Winne (1989) showed that advance organizers only promoted learning among students who successfully linked the organizer to the new content of the lesson. For example, the organizer in Figure 5.3 attempts to provide a link between a compass and the components of a new software system. However, the high number of meaningless acronyms placed around the visual makes it more confusing than helpful. In contrast the visual organizer in Figure 5.4 uses a familiar water pressure concept to introduce the concept of electrical resistance.

An expository organizer provides a context for learning new lesson content. The expository organizer is appropriate for learners who do not have related prior knowledge and who will benefit from a high-level view of the content contained in the lesson. Expository organizers may be presented with both text and graphics. However, because of their ability to efficiently capture a large amount of information, a graphic either alone or accompanied by text makes a good candidate for an expository organizer.

To experience the benefits of an expository organizer, read the text following this sentence and rate your understanding of its meaning from a low of 0 to a high of 7.

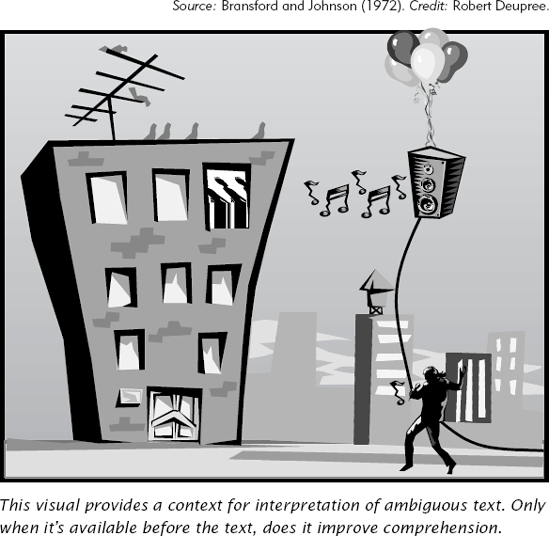

If the balloons popped, the sound would not be able to carry since everything would be too far away from the correct floor. A closed window would also prevent the sound from carrying since most buildings tend to be well insulated. Since the whole operation depends on a steady flow of electricity, a break in the middle of the wire would also cause problems. Of course the fellow could shout, but the human voice is not loud enough to carry that far. An additional problem is that a string could break on the instrument. Then there would be no accompaniment to the message. It is clear that the best situation would involve less distance. Then there would be fewer potential problems. With face-to-face contact, the least number of things could go wrong.

After completing your rating, look at Figure 5.5. Now reread the text and rate your understanding a second time. Compare your ratings with the actual experimental results shown in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1. Comprehension Ratings for the Balloon Passage Under Different Visual Conditions.

No Visual | Visual After | Visual Before | Maximum Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

From Brandsford and Johnson (1972). | ||||

Comprehension Ratings: | 2.3 | 3.3 | 6.1 | 7.0 |

Bransford and Johnson (1972) read the balloon passage to three groups as follows. Group one never saw the serenade visual. Group two saw the serenade visual after they heard the passage. Group three saw the visual before they heard the passage. Table 5.1 summarizes the participant comprehension ratings. Note that the ratings of those who saw the visual after hearing the story are about the same as the those who never saw the visual. The results are dramatic evidence for the power of a visual to provide a context for understanding content. However, any visual intended to serve as an advance organizer is only effective when it is presented prior to the main lesson content. The expository organizer promotes learning because it provides a structure for hanging on the details. Working memory has a place to put each piece of new content it absorbs without having to juggle what, without an organizer, appear to be random pieces of data.

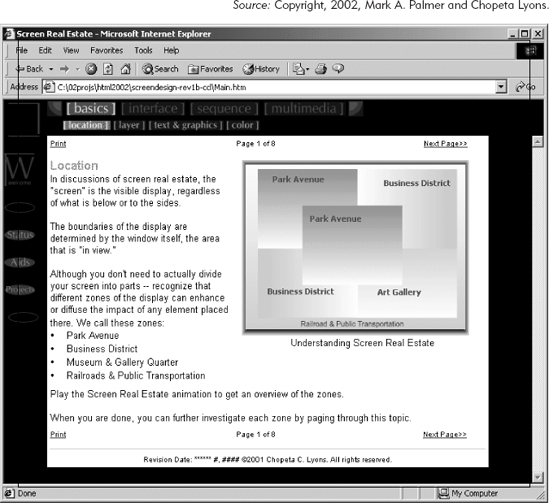

A successful expository organizer provides a high-level "skeleton" of the content to be presented in the instruction. Too much detail in the organizer will overload the learner. Insufficient or meaningless detail will not provide an effective content prestructure. Figure 5.6 shows a graphic expository advance organizer that overviews four main real estate areas of a screen. This organizer is followed by detailed information on each of the four screen areas.

In the first half of this chapter, we looked at using graphics in the form of comparative organizers to activate relevant prior knowledge or in the form of expository organizers to present a context for learning of new content. In this section we will look at the damaging effects of seductive visuals placed early in a course or lesson.

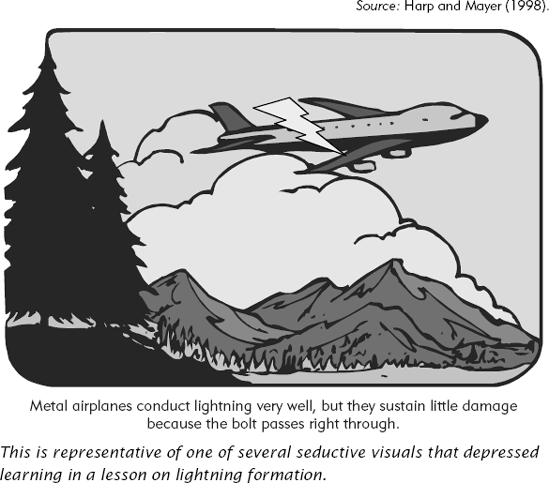

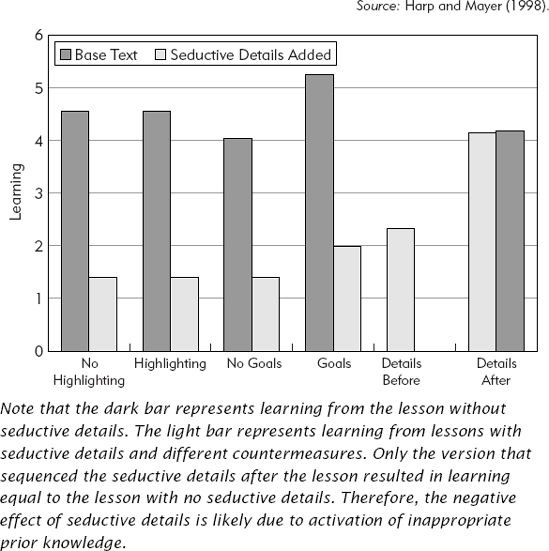

Garner, Gillingham, and White (1989) were the first to document the harmful effects of textual details that were related to the topic but not directly relevant to the goal of the instruction. They called such additions seductive details. More recently, Harp and Mayer (1998) documented the negative effects of seductive text and seductive video inserted into science lessons. They inserted either text or video clips into a basic multimedia lesson on lightning formation. The inserts illustrated extraneous information such as what happened when people or airplanes were struck by lightning. Figure 5.7 shows an example of one of these seductive visuals. Readers enjoyed the inserts. They rated them as interesting and entertaining. However, in comparisons of learning from materials with and without the seductive details, both retention and transfer were significantly better when the details were omitted. In six experiments, lessons without seductive details resulted in an average learning gain of 105 percent! Mayer terms the negative effects of emotionally arousing materials a coherence effect (Clark and Mayer, 2002; Mayer, 2001).

Because, when compared to instructor-led classes, e-lessons are especially susceptible to high learner dropout rates, designers are often tempted to use seductive visuals and words to spice up the training. For example, the screen shown in Figure 5.8 is an example of the type of fantasy themes sometimes used to liven up dry technical content. The goal of these kinds of edutainment visuals is to make the training engaging and exciting. However, the fantasy treatment is not related to the lesson objective. Chances are that learners will remember more of the graphic treatment than any content presented in the text.

Although the damaging effects of seductive visuals and text have been known for some time, only recently have we understood why. Table 5.2 summarizes three possible mechanisms whereby seductive details might do their damage. It could be that seductive visuals distract the learner and thus draw attention away from critical content in the lesson. A second possibility is that seductive visuals interfere with building a coherent mental model by blocking the integration of related text and visual content. A third possibility is that seductive visuals activate inappropriate prior knowledge or build inappropriate high-level knowledge that disrupts the integration of new content with prior knowledge.

Table 5.2. Three Possible Mechanisms of Seductive Detail Damage.

Mechanism | Description | Counter Measure |

|---|---|---|

Distraction | Draw learners' attention away from the important content in the lesson | Highlight important lesson content |

Disruption | Interfere with the organization of the content into a meaningful structure in working memory during learning | Add preview sentences and number the steps in the process to reinforce organization of content |

Activation Wrong Prior Knowledge | Activate the wrong prior knowledge and therefore disrupt the construction of new mental models | Place seductive details at the end of the lesson |

To distinguish among these possible mechanisms, Harp and Mayer (1998) used three different techniques as countermeasures as summarized in Table 5.2. Each countermeasure was added to a lesson containing seductive details and learning was compared to lessons with seductive details (that did not have any counter measures) and to lessons that did not include seductive details. An effective counter measure should overcome the negative results of seductive details and therefore result in learning similar to lessons lacking seductive details.

As one countermeasure, Harp and Mayer highlighted important content in lessons with seductive details to offset a possible distraction effect. Highlighting is an effective mechanism to draw the learner's attention to the key lesson content. To offset a possible loss of coherence, a second countermeasure added preview sentences and numbered the steps involved in the scientific process to make the organization of the content more explicit. A third countermeasure placed the seductive information either at the beginning or at the end of the lesson. If the negative effects of seductive details are due to activation of inappropriate prior knowledge, placing them at the end of the lesson should eliminate most of their damaging effects.

Figure 5.9 shows the effects of the three countermeasures. Only the versions that varied the placement of the seductive details made a difference. Placing seductive details at the start of the lesson depressed learning whereas placing them at the end of the lesson had minimal negative effect. The authors conclude that it is likely that seductive details activate inappropriate prior knowledge. Therefore, either seductive details should be omitted or they should be placed after the main body of the lesson (Harp and Mayer, 1998).

In this chapter we have summarized three guidelines related to the use of graphics to activate prior knowledge. Visuals can be used as comparative advance organizers to activate related prior knowledge stored in long-term memory. Visuals can also be used as expository advance organizers to give learners a high-level preview of the content of the lesson. Finally, visuals such as exotic thematic treatments should not be used early in a lesson as they are likely to activate inappropriate prior knowledge.

In the next chapter we summarize what we know about use of graphics to manage cognitive load in working memory. Working memory is the center of active processing that results in learning. However its capacity is very limited. Therefore, a critical function of instruction is to manage cognitive load in ways that reserve working memory resources for learning purposes.

CHAPTER OUTLINE

What Is Cognitive Load?

Sources of Cognitive Load

Guideline 1: Use Graphics Rather Than Text to Represent Spatial Content

Evidence for the Value of Visuals to Present Procedural Information

Guideline 2: Plan Graphics That Are Consistent in Style and Low in Complexity

Guideline 3: Explain Complex Graphics with Words in Audio

Evidence for Effectiveness of Audio to Describe Visuals

Guideline 4: Use Words or Graphics Alone When Information Is Self-Explanatory

Evidence for When to Add Words to Diagrams

Guideline 5: Teach the Components of a Complex Visual Display First When You Need Learners to Acquire Deeper Understanding

Evidence for Chunking and Sequencing Graphics

Graphic Benefits Depend on Graphic Functions