TWELVE

Implementing Ideas

The best ideas will be of no value if they are not put into action to resolve a challenge. In some respects, idea implementation is more important than idea generation.

IMPORTANCE AND NATURE OF IMPLEMENTATION

Next to redefining the problem, this last component of the innovation challenge process may be the most critical. A high-quality idea that appears to have a high probability of resolving a problem will be of little value if it is not implemented properly. Although this statement may seem obvious, it is extremely important when you consider that it is only by taking action that a problem can be resolved. However, this action must be of the right type; inappropriate action may magnify a problem—rendering the chosen solution obsolete—or it may create entirely new problems. The key to avoiding both of these outcomes is effective implementation planning.

However, there may be resistance to taking the time to plan for implementation. Many people become impatient and lazy after they have gone through the process involving framing a challenge, generating ideas, and evaluating and then selecting the best ones. Having already devoted considerable time to dealing with a problem, organizations often are eager to terminate all problem-solving activities once they have selected a final solution. In addition, they usually have exerted so much effort in the previous stages that they begin looking for easy ways to avoid further dealings with the problem. “Let’s just get it over with” is frequently heard at this point in the process. Moreover, the amount of time left to deal with a challenge may have been reduced, resulting in increased pressure to get a challenge resolved. Consequently, the attitude often is to do something, but it can leave out consideration of the consequences involved.

Although it may be normal for group members to experience such feelings, becoming impatient or looking for shortcuts at this stage could jeopardize problem resolution. Creative problem solving is a cumulative process, with each step building on the preceding one. If this is disregarded and the final solution is not implemented properly, all previous efforts may have been in vain. As much planning and care should be devoted to implementation as were devoted to the previous stages. Remember Murphy’s Law: “If anything can go wrong, it will.”

At its most basic level, implementation is a creative problem-solving process. A gap exists between what is and what should be—and actions are required to close this gap. In this case, the what is refers to the potential solution selected for resolving the focal problem and the what should be is the application of this solution to the focal problem. All the actions taken to apply the potential solution to the problem then constitute the implementation process.

From this perspective, a specific implementation task is a problem only if the original, focal problem is still perceived as being a problem. Problems and our perceptions of them often change over time. While a group is working on a problem, the characteristics of the problem may change over time. As a result, the solution developed by the group may no longer be adequate. Or the original problem may have changed so much that it is no longer a problem. In either of these instances, implementation would not be a problem. If the original problem has changed or disappeared, there is no reason for a group to bother with implementation.

Although this may appear obvious, it does highlight the need for groups to check on their problem perceptions periodically. Just as it is important to frame a challenge adequately at the outset of problem solving, perceptual frames must be evaluated throughout the process. This type of check is especially important immediately prior to implementation; otherwise, considerable resources may be expended unnecessarily. If it appears that the problem has changed—that is, it has been intentionally or unintentionally reframed—a group must either redefine the problem or modify the solution before implementing it. The choice will depend on the extent to which the problem has changed. However, if the wrong decision is made, then the wrong problem may be solved. Nevertheless, assuming that the original problem still exists and the chosen solution appears appropriate, you can proceed with implementation.

CHANGE AND IMPLEMENTATION

One of the first considerations in implementing solutions is the general concept of change. Most people fear change. Or, at least, they dislike it and try to resist it. “Don’t rock the boat” is an expression frequently heard when any type of change is proposed.

In organizations, the issue of change is especially complex because many parts of an organization are interrelated. According to basic systems theory, a change introduced into one part may have a direct or indirect effect on one or more other parts. For example, if workers in department A have their jobs enriched in an attempt to increase their productivity and workers in department B do not have their jobs enriched, the change may backfire. Although the productivity of workers in department A may increase, the workers in department B may resent not being included and retaliate by lowering their productivity. The result might be a net loss in productivity.

Related considerations involved in implementing changes are the degree of employee involvement in a change, the extent to which employees are affected, the magnitude of the change, whether or not the change was requested, the amount of resistance to the change, and the effects of the change on employee attitudes. Because implementing ideas involves change, either directly or indirectly, groups must be aware of all considerations when planning for implementation.

If other people need to be involved in implementing an idea, they should be included in the planning process. Inclusion of others is especially important when they will be affected significantly by implementation of an idea. Broad changes that are likely to affect many people also require input from others. Furthermore, involvement of others is necessary whenever a change is not requested, since unrequested changes are more likely to be met with resistance and have a negative impact on employee attitudes and morale.

To overcome resistance to change when implementing ideas, follow these general rules of thumb:

•Involve other people in the entire problem-solving process, including implementation, whenever:

a.They need to be involved.

b.They will be affected directly by the idea.

c.The change is broad in scope, and the change is not requested.

Of course, not everyone affected by a change will want to be involved, and time or logistical considerations may limit the amount of involvement possible. Nevertheless, an attempt should be made to involve as many other people as needed.

•Be as specific as possible about the amount and type of change likely to result from implementing an idea. Nothing is more likely to create resistance than ambiguous messages about a change. Most people fear the unknown more than a specific change. Providing vague information about a change is a sure way to reduce the chances for successful idea implementation.

•When planning for the implementation of a change-producing idea that will affect others, stress the personal benefits to be obtained if the idea is implemented. If people can see some personal gain or benefit from an idea—no matter how small the benefit may seem to you—the path to implementation will be smoothed considerably.

•Whenever possible, create shared perceptions within groups about the need for a change. If the need for a change develops from within a group, it is more likely to be supported.

•Identify key opinion leaders within the larger organization and convince them to support the change. Again, just as input from stakeholders during challenge framing is critical, so it is at the end of the process as well. It is much easier to convince a small number of individuals about the need for a change than it is to convince an entire organization. Once the opinion leaders are convinced of the need for a change, they can help convince others. These opinion leaders need not be in formal positions of authority, however. Change may receive broader support if informal leaders are perceived as supporting the change.

IMPLEMENTATION GUIDELINES

The change guidelines just discussed are general considerations involved in implementing ideas. Although they are useful by themselves, successful implementation requires a more specific approach. The implementation planning process is more likely to result in a resolved challenge if a group uses more structuring than is provided by broad change principles.

Very often, an idea must be “sold” before it can be implemented. In highly centralized organizations, where lines of authority are drawn clearly, most new ideas must receive higher approval. In these organizations, all proposed changes must go through channels. And in order to move through the channels, an idea must be sold at each level. But not all ideas must be sold to an authority structure. In many cases, ideas must be sold laterally in an organization or to groups or individuals outside an organization. The process involved in selling ideas laterally or vertically is essentially the same. The only difference is the level at which the ideas must be sold.

The activities involved in selling an idea usually precede actual implementation of the idea. Of course, not all ideas need to be sold. Depending on the degree of involvement in formulating an idea, the amount of trust placed in the idea formulators, and the perceived impact of the problem on others, an idea may encounter little opposition. However, not all ideas will be accepted widely, and steps must be taken to gain acceptance.

Gaining acceptance for an idea by attempting to sell it is just as important to implementation as applying a solution to a problem. If the necessary acceptance is not gained, the idea cannot be implemented and the problem will not be solved. Thus, a group must devote some attention to developing a strategy for selling its ideas.

In general, such a strategy should go hand in hand with the overall implementation strategy. Because gaining acceptance of an idea is an integral part of implementation, the activities involved in selling an idea should flow together with those involved in applying the idea to the problem. If these activities are not aligned and coordinated, the idea may not solve the problem. Selling and implementing ideas are complementary activities that must be considered simultaneously.

In addition to the obvious need to sell an idea before it can be implemented, there are at least two reasons why selling an idea is important to its implementation. First, the feedback that a group often receives while attempting to sell an idea can provide information relevant to implementation. People may offer many suggestions that the group can use to smooth an idea’s implementation. Or, someone to whom an idea is being sold may be able to provide resources to help ensure successful implementation. Second, there is the psychological support and commitment that often result from selling an idea. If an idea is sold, those who “bought” it will be more likely to support it through the rest of the implementation process. Just knowing that significant others support and are committed to an idea can help ease the task of those responsible for implementation.

![]()

The following implementation guidelines will help you develop an overall strategy. If you decide that an idea does not need to be sold, you can omit the steps concerned with making an idea presentation.

1.Develop and evaluate goal statements. The first task of the group is to develop goal statements that accurately reflect the purposes of the implementation process. Although group members often assume their implementation goals are understood by others, this is not always the case. Thus, it is important that these goals be made explicit at the outset and be understood clearly by all group members.

Goal statements should be specific, clear, and realistic and should include a time schedule. Sweeping generalizations, ambiguous wording, unrealistic assessments of resources, and omitted time schedules should be avoided. For example, the following statement for selling an idea would not satisfy these criteria:

To convince the board of directors that our piece-rate plan is the best and most inexpensive idea for improving worker productivity.

A better goal statement might be:

By the end of this quarter, we will meet with the board of directors to gain approval for a piece-rate plan that is projected to increase worker productivity by 5 percent and to cost no more than $20,000 to implement.

Similarly, this statement for applying an idea would be inappropriate:

To train workers to use new computer software programs.

A better statement of this goal might be:

By March 15, workers in departments A and B will be trained to use the new versions of Microsoft Office. The training will take place in conference room C from 9:00 A.M. to 4:00 P.M. every Friday between now and March 15.

Frequently, a group will need to make several attempts at developing these statements. When the group selects the final statements—one for idea selling, if needed, and one for applying the idea—it should evaluate them to ensure they satisfy all the criteria. Furthermore, the leader should make certain all group members clearly understand the statements.

2.Assess your resources. Implementation resources are the means used to accomplish the goal statements. Whatever is needed to sell an idea and apply it to a problem is a resource. Such things as information, time, people, and physical considerations are categories of resources that need to be assessed.

3.Assess the needs of the people to be influenced. If an idea needs to be sold, the group should consider the needs of the people who must buy the idea before it develops a sales presentation. Most people will respond favorably to an idea if they believe it will satisfy one or more of their basic needs. If you can determine what these needs are, you will increase the chances of getting your idea accepted.

Examples of needs you should consider are:

Power and control |

Being liked |

Security |

Recognition |

Affiliation |

Impressing others |

Personal growth and development |

Being seen as creative or intelligent |

Helping others |

Task accomplishment and |

Freedom |

completion |

Dominance |

Avoiding crises |

Of course, these needs are only representative of the many needs we all have. Take time to consider what other needs might be important to the person (or people) you and your group want to influence.

Assessing these needs can be a difficult task, since it usually is not possible to administer a psychological test of needs. Even if you could administer such a test, you still would need to interpret it in a valid manner—a task that would require professional assistance. How, then, might you assess needs without administering a psychological test? The answer lies in your powers of observation. Although certainly not as valid and reliable as a scientifically tested instrument, observational data can provide some clues.

The first thing you should observe is how the decision maker behaves. What patterns of behavior seem to characterize this person over time? For example, in group meetings, is the decision maker the one doing most of the talking? Does he or she tend to discount the opinions of others? If so, this person may be exhibiting signs of a need to control or dominate others. Another thing to observe is how the decision maker behaves during stressful situations, for example, in a crisis. During times of intense stress, primary motives are more likely to appear. Identify these motives and you may have another clue to the decision maker’s needs.

Two additional things to observe are personal possessions and hobbies. An individual’s car, house, books, clothes, and other possessions can indicate the types of things he or she values. If the decision maker drives a current Ford pickup truck, he or she is communicating values different from those of someone who drives the latest model Lexus sedan. Hobbies can reveal needs in a somewhat similar manner. A person who spends a lot of free time collecting, categorizing, and organizing radio knobs, for example, is likely to value detail work and have an inquisitive mind. (The fact that the person collects something like radio knobs also should reveal something!)

A slightly different way to assess the needs of a decision maker is to consider that all people have challenges they would like to resolve. What challenges of the decision maker could your idea solve? What problem gaps (between the what is and the what should be) could your idea help close? If you can identify these problems and structure your idea presentation around some of them, you should find the decision maker highly receptive.

4.Assess your implementation strengths and weaknesses. You have strengths and weaknesses that can either help or hinder the implementation of ideas. To implement an idea successfully, you first must acknowledge that you have strengths and weaknesses. Assuming that you have just strengths or just weaknesses can lead to self-defeating behavior. Once you acknowledge that you have both strengths and weaknesses, you must become aware of what they are. The only way you can have any measure of control over the implementation process is to acknowledge that some things about you will help and some things will hinder implementation. Identifying these things and assessing their contribution to implementation is the key to many successfully resolved challenges.

In group settings, the net effect of all the members’ strengths and weaknesses must be evaluated. For example, if most members are proficient at planning and only one or two are proficient at carrying out plans, an imbalance may exist. However, if only one or two members are needed to carry out a plan, then there actually may be a functional balance, since the imbalance of strengths and weaknesses will not prevent successful implementation. Each group must determine whether specific imbalances will be helpful or harmful, functional or dysfunctional.

To assess a group’s implementation strengths and weaknesses, you first should make a list of all activities that need to be performed. Next, have each group member list which activity is a strength or a weakness that he or she possesses. Encourage the members to be realistic. Many people tend to overrate their strengths and weaknesses. If you are the leader, you will have to make the final determination. Finally, match people with activities based on their ability to perform those activities.

Although this approach may seem obvious, it is often overlooked because of other considerations. For example, group leaders often assign some tasks on the basis of favoritism or to repay a previous contribution made by a member. Assigning implementation tasks in this way not only will jeopardize implementation but also may create ill feelings among the other group members.

Of course, all this assumes that a group will be involved in implementation. Often, this is not the case, either because there is not enough time or because the task simply does not require the efforts of more than one or two people. Selling an idea, for instance, is usually handled by the leader and possibly one or two others. In this regard, the leader and any others involved will need to assess their idea-selling strengths and weaknesses. Note that selling strengths and weaknesses may differ considerably from implementation strengths and weaknesses. As a result, separate assessments will need to be conducted for these two activities.

5.Analyze idea benefits. Assuming that an idea must he sold before it can he applied, you need to make an analysis of its major benefits. Not only will such an analysis help to produce a more convincing presentation; it also will help the idea presenters in understanding the idea. This understanding can prompt suggestions for eventual implementation. In addition, while the group analyzes an idea’s benefits, some last-minute modifications to improve the idea’s quality may be suggested.

Analyzing benefits is a divergent process similar to generating ideas. The first step is to list all the major features of an idea while withholding all evaluation. Next, generate a list of benefits for each feature listed. The list of criteria used to select the idea may help do this. Then select the benefits most likely to persuade the decision maker of the idea’s worth. If any idea modifications are suggested during this activity, decide whether you want to include them, and then reassess the idea’s benefits.

As an illustration of benefit assessment, suppose that your idea for keeping drunk drivers off the highways involves mandatory installation of a Breathalyzer in every car. The assessment might be set up as shown in Figure 12-1.

6.Prepare for the presentation. If you must make a formal or an informal presentation of your idea, you should spend some time preparing. Nothing can doom a proposed idea more quickly than a poorly conducted presentation—except, perhaps, a poor-quality idea. Thus, any investment in preparation should result in high returns.

Some of the elements involved in preparing for a presentation are:

•Time. Avoid Mondays and Fridays; try to schedule the presentation in midmorning or midafternoon, but not too close to the lunch hour.

•Location. A pleasant, comfortable physical environment is best; if possible try to use a location away from the regular work environment.

•Length. Set a time limit and build the presentation around it; keep it as short as possible.

FIGURE 12-1. Example of a benefit analysis for idea implementation.

Features |

Benefits |

Compact size. |

Takes up little space. |

Few mechanical parts. |

Requires little maintenance; unlikely to break down very often. |

Ignition system hookup automatically prevents car from starting when driver’s alcohol content exceeds legal limit. |

Drunks cannot drive. |

Alarm sounds when driver’s alcohol content exceeds legal limit. |

Police will be alerted. |

•Presenter. Select the person with the best presentation skills; make sure this person is not viewed unfavorably by the decision maker.

•Support. If possible, cultivate advocates for your idea before the presentation. For presentations to a group, this would mean contacting the members in advance; for presentations to one person, you could try to gain support from others who are close to this person.

•Receptivity. Try to anticipate how receptive the decision maker is likely to be to your idea. If nothing else, you may be motivated by knowing you will be entering a hostile climate.

•Funding. Obtain any funds needed for the presentation; review any funding required for your idea; develop alternative approaches to funding the idea.

•Materials and Equipment. Inventory all materials and equipment needed for the presentation; obtain missing materials and equipment.

•Compromising. Decide which and how many features of your ideas you would be willing to give up in order to gain acceptance. Or, if you are willing to give up your idea, determine what other ideas might be acceptable.

•Data. If relevant, gather any data that might reinforce or support the value of your idea (e.g., testimonials, statistics, observations, experts).

7.Conduct the presentation. If you have done a thorough job of preparing, the presentation itself should be a relatively simple task. All you—or the chosen presenter—need to do now is apply the insights gained from assessing your resources, strengths and weaknesses; the needs of the decision makers; the idea benefits; and the presentation considerations. However, the manner in which you apply these insights will determine how successful you will be. Part of what is involved is style and part is substance. That is, how you present your idea can be just as important as what you present. Before you conduct your presentation, consider the following tips:

a.Try to adapt yourself to your audience. If your audience is highly analytical and skeptical, structure your proposal accordingly. If your audience is more intuitive and visually oriented, make sure that you use visual aids and emphasize wholes rather than parts.

b.Start on time. Failure to start on time may upset your audience unnecessarily and create negative attitudes at the outset. Being prompt won’t help your presentation, but starting late will certainly hurt it.

c.Avoid memorizing your presentation. If you speak naturally (guided only by a memorized outline), you will seem knowledgeable and be much more convincing than if you deliver a memorized talk.

d.Be yourself. Never try to emulate someone else’s presentation style. Instead, focus on your idea and worry about how it looks, not how you look.

e.At the outset, describe what you hope to accomplish and how you will do it. The more straightforward you are, the more credible your idea will appear.

f.Avoid clichés and jargon. Unless both you and your audience use clichés and jargon on a regular basis, avoid them. If you use them inappropriately, you may come across as being more concerned with impressing others than with selling your idea.

g.Remain loose. Try not to be overly serious, especially when referring to yourself. Use humor when appropriate, and stay open to all comments and questions.

h.Keep your eyes on your audience. If you don’t maintain eye contact, your audience may think you have something to hide.

i.Avoid repetitious statements. Although you should restate your points to get them across, try not to repeat yourself frequently. Don’t linger too long in discussing any one point.

j.Try to avoid distracting mannerisms. Continually pulling at your collar or other obvious mannerisms may shift attention from your idea to you.

k.Don’t criticize competing ideas. Try to be objective and nonjudgmental. Both you and your idea will be seen as being more credible if your presentation is balanced and fair.

l.Listen effectively. Try to understand the content and feeling of what is being said to you; practice using reflective feedback. For example, “As I understand it, you think that . . .”

m.Don’t exaggerate. Never make unsubstantiated claims about the worth of your idea. Let the idea sell itself.

n.Respond directly to all questions. Be as specific as possible in your answers, and be sure you deal with every question you are asked. Avoid generalities or shifting the focus of a question. You don’t want to appear evasive.

o.Try not to oversell your idea. Once it appears that you have been successful, conclude your presentation. Otherwise, it may appear you are not very confident about your own idea.

p.Finish on time. End your presentation when you said you would. Finishing a couple of minutes over your allotted time is seldom a problem, especially if the audience shows a lot of interest. However, exceeding your time by very much is likely to upset the audience, most of whom probably consider their time valuable.

8.Develop an implementation strategy. You and your group already should have thought out the basics of your implementation strategy, and you should have included them in your presentation. For some ideas, how they are implemented may be just as important to your audience as the nature of the ideas themselves. However, if you have not already developed an implementation strategy, now is the time to do it. Or, if you have developed an outline of a strategy, it now should be filled in and developed. You must have a plan to guide implementation.

Most of the techniques described in the next section can be used for this purpose. However, the group leader will have an important decision on the way these techniques are used. Specifically, leaders need to decide whether other group members should be involved. If there is sufficient time, try to gain the acceptance of others. This is critical to effective implementation. If the others are likely to benefit either personally or professionally, you should involve them. Of course, if these conditions do not exist, you must consider implementing the idea by yourself.

9.Implement the idea. The last step in the implementation process is to apply the idea to the problem. If the preparation and planning have been conducted thoroughly, the problem should be resolved with little difficulty. Of course, not all implementation obstacles can be anticipated, and the problem may not be resolved as expected. When this occurs, you should review the implementation process and devise new plans. Note, however, that one of the techniques to be described, potential problem analysis, can avert many implementation problems. Whenever possible, use this technique before using any of the other implementation methods.

IMPLEMENTATION TECHNIQUES

With the exception of potential problem analysis, the techniques described in this section represent variations of strategies that can be used to implement ideas. Some are more complex than others, but all are capable of providing the structuring needed for implementation activities.

In selecting from among these techniques, there is one major factor that must be considered: the complexity of the idea. When an idea has multiple facets (in terms of time and activities) that you must deal with, you need to use more complex techniques. For these types of problems, PERT is most appropriate; for moderately complex ideas, flow charts are appropriate; and for relatively simple ideas, the five Ws and time/task analysis are appropriate (the appropriateness of the copycat technique will depend on the particular method being copied).

Of course, the decision to use any of these methods also depends on the group’s needs and preferences in addition to many other variables. For example, even though PERT should he used to implement a complex idea, there may not be sufficient time to do so. The group might have to use another technique instead. Or the group might decide to modify the way the procedure is used to reduce the amount of time required.

Potential Problem Analysis

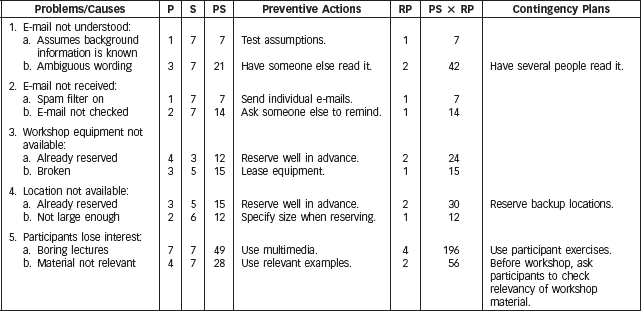

Originally developed by Kepner and Tregoe and later modified by Woods and Davies, potential problem analysis (PPA) serves as a bridge between implementation planning and actual implementation of an idea. In contrast to the other implementation techniques, PPA is designed specifically to anticipate possible implementation problems and to develop countermeasures. As a result, you should use PPA before using any other implementation method. Based on earlier versions and with some modifications by me, the major steps for conducting a PPA are:

1.Develop a list of potential problems. Withhold all evaluation and think of everything that could possibly prevent the idea from being implemented successfully.

2.Determine possible causes of each problem listed.

3.Using a 7-point scale, estimate the probability of occurrence and the seriousness of each cause (1 = low probability of seriousness; 7 = probability of seriousness).

4.Multiply each probability rating by each seriousness rating, and sum the products. These products are known as the probability-times-seriousness scores.

5.Develop preventive actions for each cause. Think of what could be done to eliminate or minimize the effect of each cause.

6.Using a 7-point scale, estimate the probability that a cause becomes problematic after a preventive action is taken (1 = low probability; 7 = high probability). This estimate is known as the residual probability. For example, if the likelihood that a cause will occur originally is estimated to be a 6, taking a preventive action might reduce the likelihood to, say, a 2 (depending on the circumstances).

7.Multiply each probability-times-seriousness score (obtained in step 4) by the corresponding residual probability rating, and record the products.

8.For each product obtained in step 7, develop as many contingency plans as your time and resources permit.

Figure 12-2 illustrates how PPA might be applied. In this figure, the idea being implemented involves conducting an in-house workshop on innovation challenges. For this idea, five potential problems were identified and two possible causes are listed for each problem. After all the ratings and preventive actions were determined, contingency plans were developed for the four highest scores in the PS x RP column. Of these plans, the most important ones appear to deal with the potential problem of participants losing interest.

The usefulness of PPA is exemplified best by the maxim: “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” The amount of resources consumed in the systematic anticipation of potential problems and development of countermeasures will be well justified if the idea is implemented successfully. For relatively important implementation tasks, the short-run costs of PPA will be offset, in most cases, by the long-run benefits. Another major advantage of PPA is that it can be used easily by both individuals and groups. Furthermore, the ratings can be obtained in groups quite efficiently by using averages whenever time is not available to achieve consensus.

A disadvantage of PPA is that it is not always possible to identify all potential problems and likely causes. Leaving out just one major problem cause could doom implementation success. As a result, considerable care must be used to generate as many potential problems and causes as possible. A second disadvantage of this method concerns the amount of time expended relative to problem importance. Spending time to do a PPA must be weighed against the costs of not solving the problem. If a group decides to use PPA, it will need to balance the amount of time spent against both the need to solve the problem and the likelihood of encountering major obstacles. It would make little sense to spend several days on an implementation task that involves a relatively unimportant problem and comparatively few major obstacles.

FIGURE 12-2. Using PPA to anticipate workshop problems.

Copycat

If your idea is similar to one that has been implemented before by other groups or individuals, you can be a copycat. Instead of trying to reinvent the wheel, you can borrow someone else’s implementation strategy. However, before you do this, make sure that the strategy you borrow will work with your idea. Even a relatively minor difference between your idea and another one could preclude using a borrowed strategy. Nonetheless, there will be many situations in which only a few modifications will be required, and thus considerable savings in time and effort will result.

Five Ws

In addition to being useful for reframing challenges, the five Ws technique can be very useful for implementing ideas. For relatively simple implementation tasks, this method provides an efficient and orderly means for seeing that an idea is applied to a problem. (It also can be used quite easily in conjunction with other methods.) The major steps are:

1.Ask who, what, where, and when in regard to implementation tasks. For example, you might ask: Who will implement the idea? What will they do? Where will they implement the idea? And when will they implement the idea? Then answer each of these questions, being as specific as possible.

2.Ask why for each of the preceding questions and answer each question. For example: Why should these people implement the idea? Why should they do what they are going to do? and so forth. (By asking why, you provide a rationale for each implementation action and ensure that no major activities are overlooked.)

3.If asking why reveals any overlooked implementation activities, revise the implementation strategy.

4.Implement the idea.

Flowcharts

When a sequence of activities is required to implement an idea, flowcharts can be used to guide the process. Similar to the diagrams computer programmers use to depict the operations needed to carry out a program, flowcharts provide an efficient means for structuring implementation activities. The basic elements of a flowchart are activities, decision points, and arrows for activity indicators. Using these elements, a flowchart can be constructed as follows:

1.State the objectives to be achieved, including the desired end result.

2.Generate a list of all activities needed to implement the idea.

3.Put the activities in the order in which they must be performed.

4.Examine each activity and decide whether any questions must be asked before the next activity can be completed.

5.Write the first activity at the top of a sheet of paper and draw a box around it. Draw an arrow from this box to the next activity or decision point. (Draw a diamond shape around questions at decision points.)

6.Continue listing each activity and decision point in sequence until the terminal activity has been reached.

7.Using the flowchart as a guide, implement the idea.

Examples of flowcharts can be found in Chapters 2 and 3 in the figures used to illustrate the Q-banks and C-banks. The best way to learn how to make flowcharts is to practice using them. Always make a rough sketch first and don’t be afraid to add your own modifications. For instance, many people find it helpful to add time estimates for each activity. Moreover, software programs now exist to facilitate drawing them.

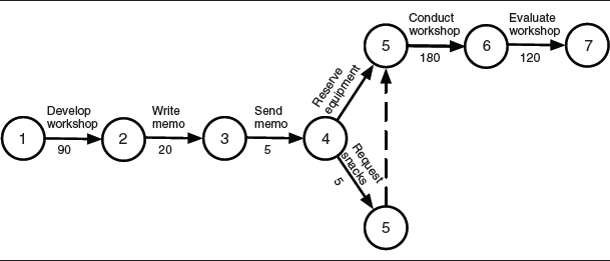

PERT

The PERT method (program evaluation and review technique) was developed by the military in the 1950s to facilitate the development of a new missile project. It is a relatively complex implementation procedure and requires the use of a computer for large projects. However, it can be adapted for smaller implementation projects and set up without any computer assistance.

The basic steps are similar to those used to construct flowcharts, except that time estimates are an essential part of the PERT method. In addition, the terminology differs somewhat. With PERT, activities are work efforts that consume resources. Activities are represented by arrows. Those places where activities begin and end are known as events and are represented by circles. Dummies are activities of zero duration that consume zero resources and are used only to maintain the logic between events and activities. Dashed arrows are used to represent dummies.

To construct a relatively simple PERT network, use the following steps:

1.Define the implementation objectives, including an end product.

2.Generate a list of all activities needed to implement the idea. Whenever possible, list subactivities as well.

3.Put the activities in the order in which they must be performed, and assign numbers to them to indicate their order. If two or more activities need to be performed at the same time, assign each of these activities the same number.

4.Construct the basic PERT network by connecting the events and activities. Place event numbers in the event circles. Write activities above the arrows.

5.Review the network and make any modifications needed to ensure the network is complete.

6.Estimate the amount of time needed to complete each activity (hours, days, weeks, months, years) and write these estimates beneath the activity arrow.

7.Review the network as close as possible to the implementation target date (the time of the first event). Update the network if any information has become available that requires changes.

8.Implement the idea using the PERT network as a guide.

The actual construction of a PERT network should be guided by certain rules. The most important of these rules are:

•A previous activity must be completed before a new event can begin.

•Only a single event can be used to begin and end a network.

•All activity arrows must be used to implement an idea.

•Any two events can be connected with only one activity. When more than one activity connects two events, a dummy activity is required.

•A previous event must occur before a new activity can begin.

A PERT network is presented in Figure 12-3 to illustrate how PERT might be applied to the workshop example used for PPA. The activities involved and their assigned event numbers are:

1.Develop the workshop.

2.Write a memo describing the workshop.

3.Send the memo to the participants.

4.Reserve required equipment.

5.Request snacks for breaks.

FIGURE 12-3. Using PERT to implement a workshop.

7.Evaluate the workshop.

These event numbers and descriptions of the activities are shown in Figure 12-3. A time estimate (in minutes) for completing each activity can be found below each activity arrow. Because reserving equipment and requesting snacks are seen as activities to be performed at about the same time, a dummy activity has been included to preserve the network’s logic.

Note that Figure 12-3 presents only a very elementary PERT network. Implementing ideas that require more precise time estimates and that are more complex than the one represented here involves using much more sophisticated networks. For example, there are a variety of methods for calculating time estimates for individual activities to increase the accuracy of the time estimate for the entire process. The reader interested in these more advanced PERT procedures should consult the numerous books and software programs available on this topic.

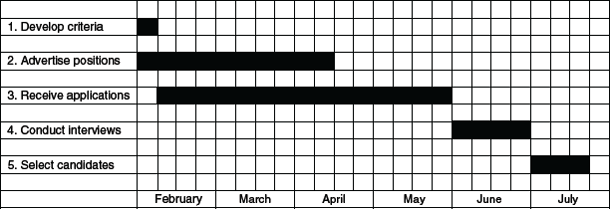

Time/Task Analysis

One of the simplest implementation techniques is time/task analysis (T/TA), also known as Gantt charts. Similar in purpose to PERT, T/TA is used by relating time requirements to implementation tasks and constructing a graph to depict the flow of events. The major steps for conducting a T/TA are:

1.List every task that must be completed to implement the idea. Be as specific as possible and try not to leave anything out—even relatively simple tasks may be critical for implementation success.

2.Estimate the amount of time available to implement the idea. Make this estimate as realistic and accurate as possible.

3.Determine how much time will be needed to complete each task. Again, try to be realistic and avoid underestimating the time required. Make sure that the time required for completing all the tasks does not exceed the total amount of time available. As a rough rule of thumb, remember that most tasks take longer to complete than people originally think they will.

FIGURE 12-4. Using T/TA analysis to select an engineering candidate.

4.Construct a graph showing the relationship between each task and its time estimate. Plot the tasks on the vertical axis and the time on the horizontal axis.

5.Implement the idea using the T/TA as a guide.

Suppose, for example, that your idea involves recruiting minority personnel to fill various engineering positions in your company. To implement this idea, you could develop a chart such as the one shown in Figure 12-4. With this chart, it is easy to see which tasks overlap each other, which ones must be done after the previous one has been completed, and the relative amount of time required for each one. As with PERT charts, more information can be found in books and online.