TWO

Question Banks:

Understanding the Strategic Terrain

Willy Sutton, a notorious U.S. bank robber in the 1930s, supposedly was asked once why he robbed banks. His answer was simple and to the point: “Because that’s where the money is!” Strategic questioning banks (or “Q-banks”) are used because asking questions is “where the answers are!” Simple as that. To understand just about anything, we need to ask questions—a basic component of natural human inquisitiveness. However, systematically asking questions in organizations—no matter how valid and useful they may be—often results in dissension and resistance among organizational stakeholders.

When Nike chairman Phillip Knight announced William D. Perez as his successor as CEO of Nike, one of the first things Perez did was undertake an extensive review of the company’s strategies and operations. He hired Boston Consulting Group and asked all managers to reply to a detailed questionnaire. One manager commented that most of the longtime employees never had to answer such questions and that surveys just do not fit with Nike’s culture. After all, if you ask questions, you might discover some answers you really don’t want to know! Nevertheless, if a company is open to such questioning, the payoff can be dramatic. The remainder of this chapter will look at Q-banks for collecting strategic information.

QUESTION BANKS (Q-BANKS)

Before innovation challenges can be created, organizations first must research the strategic terrain in terms of opportunity areas. This chapter will discuss how to use categories of strategic questions to collect data as the basis for generating innovation challenges. A focus on innovation is critical, and it should be guided by a systematic exploration of possible tactical and strategic options. This chapter will describe how to conduct Q-banks involving such areas as core competencies, customers, the company as a brand, competitive positioning, markets, and overall goals. Finally, this chapter will provide a list of sample questions for each of these areas and others as well.

At the outset of strategic planning, organizational members often are in different perceptual locations—that is, organizational stakeholders may differ in their perceptions regarding the organization’s tactical and strategic positioning with respect to a number of variables. A Q-bank is a broad process that can help an organization take a hard look at itself and increase understanding about what it does and does not do, as well as what it should do. The outcome will be a sense of potential strategic directions to pursue and the beginning of a sense of priorities.

One way to do this is to conduct a question bank, which is simply a list of questions and responses developed to help draw out information, knowledge, and perceptions of value held by key organizational stakeholders. Although a lot of this information already may exist in various documents and in the form of tacit knowledge held by organizational members, not all stakeholders may hold the same perceptions; be aligned with this information; or, even more important, be aware of some information with strategic consequences. Moreover, some information, as well as perceptions, may be outdated. A strategic, perceptual realignment, however, may help get everyone on the same page cognitively as well as psychologically. Thus, it can be quite useful to collect such data periodically.

In general, Q-banks are especially useful when an organization:

•Is trying to find its direction

•Wants to affirm all or parts of its current strategic plan

•Lacks consensus about strategy among key stakeholders

•Wants to chart a new strategic course

•Is losing market share and competitive advantage

Q-banks are not, however, a substitute for conventional strategic planning. Many organizations already have collected the information needed, but they still could benefit by involving key stakeholders or by just updating old information. Planning is a process, not an end result. Q-banks are a logical choice to use during strategic framing because the responses contain the answers needed to generate organizational challenges. (Challenge banks, or “C-banks,” are discussed in Chapter 3.) Innovative ideas then are generated from responses to the challenge questions.

A STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE TO Q-BANKS

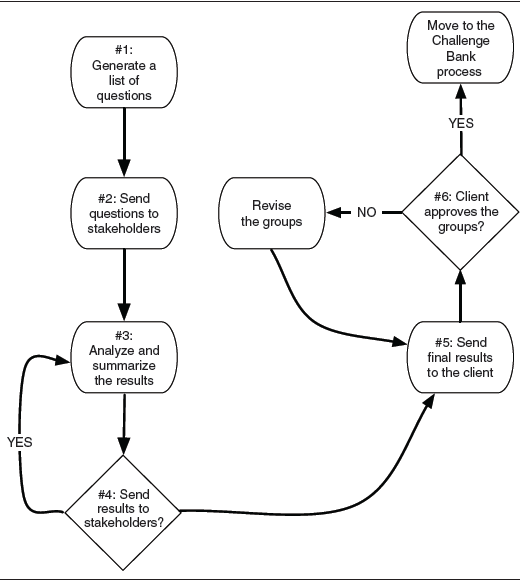

Q-bank responses eventually are used as the basis for generating potential innovation challenge questions. The basic Q-bank process is shown in Figure 2-1. A preliminary list of questions first is generated, organized into categories—for example, customer service, marketing, or branding—and sent to stakeholders for their feedback and any new questions they might want to add. The data are analyzed and summarized by categories used in the Q-bank. Any responses not falling into the presented categories are organized into affinity groups (new categories with commonalities). These data are sent to the stakeholders again for a second round of additional responses or they are sent directly to the client with no feedback. A third, final round also can be conducted if desired and time is available. (A client is any individual or group for whom the questions are generated. Clients can be internal or external to organizations. For example, an HR manager might sponsor an innovation challenge for members of the R&D division in the same company.)

FIGURE 2-1. Basic Q-bank process.

After all rounds are concluded, the results are sent to the client for approval and any suggested revisions. The list of responses then is used to generate a list of potential innovation challenge questions. Finally, this list is narrowed down to one or more challenges for ideation.

The specific Q-bank steps are as follows:

1. Generate a List of Questions

You can use all or part of the list presented next. Most organizations will not use all of the questions. Just delete those for which you already may have adequate intelligence. Make this decision judiciously, however, because it generally is better to retain questions than to delete them. Deleting one important question could make the difference between innovation success and failure. If you decide to use a relatively large number of questions, you might consider sending them out in batches with generous due dates. Advanced planning is always important in these matters.

Consider conducting a small pilot test to evaluate the quality of the questions—that is, their potential usefulness—and their readability for the intended audience. Send out a preliminary list to three or four people, including outsiders, whose opinions you respect and who would be willing to provide feedback. Ask them to do the following:

a.Make any revisions that might affect the intended meaning.

b.Suggest any additional questions that should be asked.

c.Consider the organization’s priorities and select the top twenty most important questions.

Then, incorporate their suggestions as you see fit.

A typical Q-bank is implemented by sending out a list of generic questions to key stakeholders—usually around ten to thirty—although more could be used if necessary. This can be done via e-mail and might involve one or two rounds or possibly three. At the end of each round, the responses are collected, summarized (omitting duplicates), and resent to the participants for additional responses.

Of course, not all of these questions will apply to every organization. You will have to decide which ones are best for your situation. In general, you could leave out those for which you already have sufficient information (this assumes the information is valid). Also, before even starting a Q-bank, you might consider developing a preliminary list of questions and soliciting feedback from others, especially those less likely to be biased or emotionally involved in any potential issues reflected in the Q-bank. You also might want to solicit additional questions before initiating a Q-bank.

The ultimate goals of asking and answering these questions is to uncover potential areas to explore for applying creative thinking, increasing innovation, and creating value. So, the more questions asked and the more detailed the responses, the greater the likelihood that the information generated will result in the most important innovation challenge statements eventually being generated.

A Sample List of Q-Bank Questions

A list of sample questions follows. If there appears to be some duplication among the questions, that is intentional. Sometimes, phrasing a question a little differently can elicit richer, more robust responses capable of getting at core issues.1

Our Organization

1.What does our company do?

2.What are our core competencies?

3.What is our primary vision?

4.What is our primary mission?

5.What are our core values?

6.Who are our strategic partners? Why?

Our Customers

7.Who are our customers?

8. Whom would we like to have as customers?

9.Whom do we not want to have as customers?

10.What customer needs do we meet?

11.What customer needs should we meet that we aren’t now?

12.Where are we positioned in the minds of our customers?

13.Where would we like to be positioned?

14.When should we reposition ourselves?

15.What value do our products, processes, and services provide our customers?

16.Why do our customers like us?

17.When don’t our customers like us?

Our Brand

18.What is our brand?

19.What are our subbrands?

20.What values are associated with our brands?

21.How consistently do we transmit these values?

22.What is our brand equity?

23.How do we know that?

24.What are the components of our brand equity?

25.What extensions would be best for us to explore?

26.What is our aided brand awareness?

27.What is our unaided brand awareness?

28.Should we broaden or narrow our brand? Why?

Our Markets

29.What markets are we in?

30.What markets would we like to penetrate? Why?

31.What markets would we like to segment?

32.What do we know about current markets we are pursuing?

33.What do we need to know for success in these markets?

34.What markets are we overlooking?

35.What markets should we leave or reduce our presence in?

36.Are we exploiting market trends?

Our Goals

37.Where do we want to be in one, three, or five years?

38.If anything were possible, what should we do?

39.What do we want to do in the future that we aren’t doing now?

40.What do we want to do differently?

41.How do we know when we achieve our goals?

42.Which goals, if any, should we change? Why?

43.How often do we revise our goals?

Our Competition

44.Who is our competition?

45.What are they doing right?

46.What are they doing that is not working?

47.What do we like about our competition?

48.What do our competitors’ customers like about them?

49.What do our competitors’ customers like and dislike about us?

50.Who has achieved the positive results we want?

51.How are they doing that?

52.How can we do that?

53.Who is doing something well in our industry or another?

54.What can we borrow from them (e.g., learning, tools, approaches)?

Our Innovation

55.How do we define innovation?

56.How do we measure it?

57.Do we have a strategic innovation process?

58.What is our innovation process?

59.How effective is it?

60.How do we know it is effective?

61.What are our top three to five barriers to innovation?

62.How might we overcome these barriers?

63.How do we reinforce/motivate innovation?

64.How do we reduce the motivation to innovate?

65.Do we have a way to generate and track new ideas?

66.How often do we generate new ideas?

67.What sources do we use for new ideas? Internal only? Customers? Vendors?

68.How well do we manage the ideas we generate? Why?

69.How might we manage them better?

70.At any one time, how many ideas do we have in our innovation pipeline?

71.Do we reevaluate promising ideas we once left on the shelf?

72.When do we innovate best? Why?

73.When do we innovate least well? Why?

74.How do we reward innovation?

75.How might we become more innovative?

76.What new products, processes, or services should we explore?

Our Financials

77.How is our stock valued in the market?

78.How do analysts value our stock?

79.How do we measure financial success?

80.What is our residual income?

81.How much do we invest in R&D?

82.How does our R&D investment compare with our major competitors’?

83.Should our R&D investment be smaller or larger?

84.Do we meet expected returns according to analysts’ estimates?

85.What is our return on investment?

86.What are our net margins?

87.What is our market share?

88.What should be our market share?

89.What financial value do we place on our intellectual capital?

90.What are our projected revenues for the next quarter? The next year? The next five years?

91.What products do we have that are successful?

92.Do we know why they have been successful?

93.What products do we have that are unsuccessful?

94.Do we know why they have been unsuccessful?

95.What extensions would be best for us to explore?

Our Processes

96.What are our core processes?

97.How do we measure process effectiveness and efficiency?

98.How well do we meet our goals for these processes?

99.When do our processes function best?

100.When do our processes function least well?

101.What are the greatest obstacles to internal process functioning?

102.What value do our processes add to us?

103.What value do our processes add to our shareholders?

104.What are our process inputs?

105.What are our process outputs?

106.What are our process outcomes?

107.What are our process throughputs?

108.How well do we track and manage new ideas?

109.How well do we convert new ideas into commercial innovations?

Our Shareholders

110.Who are our shareholders?

111.When are our shareholders happiest?

112.What upsets our shareholders?

113.How do we know when they are happy or upset?

114.Why are they happy or upset?

115.What value do we add to our shareholders?

2. Send Questions to Stakeholders

A stakeholder can be defined as a person with a financial, emotional, psychological, personal, or professional interest and investment in an organization and its success. This is a broader, more generic term than that of a shareholder, which typically applies to financial shareholders. Even though some shareholders also may have personal or professional stakes in an organization, all shareholders are, by definition, stakeholders. All stakeholders, however, are not necessarily shareholders since they may not have a financial stake. Stakeholders often (but not always) have a financial stake in addition to other areas of perceived ownership.

The first activity of this stage is to identify the stakeholders who should participate in a Q-bank. This can be a politically tricky decision, depending on the organization involved, a variety of environmental factors, resource availability, and the purpose of the Q-bank. In general, Q-banks should be framed in a positive light as having potential benefit for everyone, at least to some degree.

Once this list is generated, approved, and the participants agree to respond, the questions should be sent. This normally is done using e-mail, although questions can be posted on organizational Web sites, listservs, or Web sites such as www.surveymonkey.com. Another option is to use any of the numerous idea management enterprise software programs, such as www.imaginatik.com, www.jpb.com (“Jenni”), www.ideacrossing.com, or www.brainbankinc.com.

Emphasize that the focus now is only on answering the questions to use for evaluating challenges later on. Otherwise, some participants might submit challenge questions as well as ideas for resolving various challenges. If they do, analyze these data separately during the next stage.

3. Analyze and Summarize the Results

Ideally, question responses should be analyzed by two types of people: (1) the client and other internal stakeholders, and (2) external resource personnel such as subject matter experts. Two sets of eyes can help provide a more objective, yet knowledgeable interpretation of the results. So, an internal project manager might be teamed with an external consultant. However, this is not essential and might not always be practical. At a minimum, at least two internal people should review the results to ensure a more balanced, unbiased interpretation.

Duplicates should be eliminated, but ensure that a response is a true duplicate and not just similar or a variation in degree. Otherwise, potentially useful information might be discarded. This obviously can be a very subjective decision. Again, a second person could help make such decisions. If any of the responses are ambiguous, the project coordinator might contact whoever submitted the response and seek clarification.

This raises the issue of stakeholder anonymity. In general, it probably is best to present the Q-bank as being an anonymous process. You might emphasize that participants should feel free to provide their names or identifying information if they wish. Such decisions often are based on various internal political issues, regardless of the preference for anonymity. Thus, some people will want to be anonymous, fearing some form of retaliation, status differentials, or perceptions at odds with their view of what others expect them to say; other people, in contrast, may want to be identified to make a more persuasive case for some cause or issue they support. So, a decision regarding anonymity ultimately may be a political one. Nevertheless, you need to make a decision.

Sometimes, respondents may provide answers to questions not asked or they might provide solutions to various challenges not included as part of the Q-bank. If this occurs, you should organize the results into affinity groups so that there is a theme common to the responses. This can involve functional areas, strategic goals, or other aspects of commonality. If all of the responses fall within the original categories, move to the next step. If any responses do not seem to fit anywhere and represent general comments or criticisms other than the focus of the Q-bank, consider not returning them to stakeholders if you use a second or third round. Nonresponsive data are likely to create ambiguity and misunderstandings about the purpose of the Q-bank.

To illustrate the results from a typical Q-bank, consider this example from a major financial services firm. Approximately twenty upper-level managers were sent a list of thirty-six questions and asked to respond within a week. Samples of these questions and their responses are provided next. (Select responses have been altered to maintain confidentiality and only the questions with responses are repeated here.)

Our Customers

1.Who are our customers?

a.Rich people.

2.Who[m] would we like to have as customers?

a.Rich people.

b.Those who would not qualify for a prime product today but could in the future.

c.People with established credit histories.

d.Gift card users.

3.Where are we positioned in the minds of our customers?

a.Could be better.

b.Brand recognition is low.

c.Nonexistent.

4.Where would we like to be positioned?

a.We would be the number one provider of our product in the world.

b.We would like to be viewed as the premier financial services brand for our target niche market.

5.What value do our products, processes, and services provide our customers?

a.They get to finance their debt through credit card use.

b.Access to financial resources as they are needed.

6.When don’t our customers like us?

a.When we do not live up to their expectations.

b.When we reprice our products and services.

c.When they have to pay fees.

7.What values are associated with our brands?

a.Don’t know.

b.Exceptional customer service.

c.Good product at a fair price.

8.What is our aided brand awareness?

a.Not very good.

b.Nonexistent.

Our Markets

9.What do we know about current markets we are pursuing?

a.Not enough.

10.What do we need to know for success in these markets?

a.A lot.

b.How do we communicate with new and “alien” segments?

Our Goals

11.If anything were possible, what should we do?

a.Enter South America and solidify our presence in Western Europe.

b.Design an infrastructure to understand the people to whom we are offering our services and products.

c.Develop, test, and launch new products faster.

d.Become a more nimble organization that can take advantage of opportunities more readily.

e.Improve our public relations.

f.Increase profitability for the next decade consistent with the past decade.

g.Become the number one financial services company in the world.

h.Achieve financial targets related to our target markets.

12.What do we want to do in the future that we aren’t doing now?

a.Increase our penetration in the Asian market.

b.Move from a single-product marketing approach to a one-to-one marketing approach.

13.What products do we have that are successful?

a.Credit cards.

14.Do we know why they have been successful?

a.People who charge have high revolving balances.

b.People with balances often pay only a minimum and never pay off the debt.

15.Do we know why [our products] have been unsuccessful?

a.Consumer finance.

b.No brand equity.

c.No consumer trust.

d.No competitive advantage.

The value of a Q-bank can extend beyond the individual responses. What can be most telling are the questions and categories receiving responses. In this case, the category, “customers” received the most responses (15), followed by “goals” (10), “products” (7), “brand” (5), and “markets” (3). Such numbers do not necessarily indicate a priority order of concerns from a strategic perspective. It is possible that the majority are from only a few individuals. So, it is important to have a breakdown of how many people responded and the number of responses from each. If there are few respondents, then the results might not be representative of the sample of shareholders. If so, additional input should be sought.

4. Send Results to Stakeholders

This stage is a decision point in which a choice must be made about sending the results back to the stakeholders or using them to generate challenges without any feedback and sending them directly to the client. In general, results should be submitted to the participating stakeholders, unless organizational politics, time, money, or other considerations dictate otherwise. For instance, if there is an off-site retreat planned within a certain period of time and it is based on the results, there might not be enough time to solicit responses from another round of questions. Or, organizational politics could play a role if the particular situation is not supported fully by a key manager who only reluctantly approved a single-round Q-bank—perhaps for reasons known only to him or her. And, of course, time and politics combined, as well as other variables, might play a role in this decision. Regardless, if you decide to return the responses, send all including questions without responses, since a second reading might prompt additional reactions.

The purpose and obvious advantage of sending the tabulated results back to stakeholders is that they might benefit from seeing others’ perceptions. This, in turn, might enhance the quality of the output so that more realistic and appropriate innovation challenges are generated later on. Seeing others’ responses provides a larger set of stimuli that might provoke richer perceptual sets (frames) about potential challenges. The person who generates a question response might not be aware of its value in provoking challenges that need resolving. Others, however, may see the value in such a response. Finally, an advantage to seeing other responses is that the initial pool of responses may have been limited in scope, focus, or quantity. A second, or even a third, round increases the odds of collecting more relevant and useful information.

If the results of the first round are sent to the stakeholders, ask them to review all the responses and try to generate additional ones. As with Step #2, emphasize that the focus now is only on answering the questions to use for generating challenges later on. As a rule of thumb, conduct no more than three rounds, assuming time and other required resources are available. If there is sufficient time, you also might want to use the last round to solicit perceptions of priority affinity groups for the responses to each question. This could prove useful for the client when evaluating the final results and before creating the actual challenge statements for idea generation.

5. Send Final Results to Client

Up to this point, you should have kept the client informed about the results of each round. Some clients request a lot of input and want to approve the results before they are sent out for another round; others only want to see the final results. So, try to determine such preferences before starting the Q-bank.

To organize your final report to the client, use the original categories. If you have added any categories, note this so the client is aware of them. Finally, ask whether the client wants to make any changes. As shown in Figure 2-1, client approval is a decision point used to make revisions based on client feedback. Thus, if the client does not approve the list and suggests revisions, make them and resend the list to the client. Then, once the Q-bank results are approved, you can move to the next step and use the results to generate a challenge bank (C-bank).

NOTE

1.Some of these questions were contributed by Addys Sasserath of MarketQuest Consulting, e-mail to author, 1999.