THREE

Challenge Banks: Generating Innovation

Challenge Questions

In the late 1970s, Charles Schwab dramatically altered the competitive landscape of financial brokerage houses by providing investors with discounted investments. His company also was the first to offer online investing in the late 1990s and soon became the market leader in discount brokerage services. This success was not to last, however, and the vagaries of the marketplace and his retirement as CEO (although still board chair) soon led to difficult times in the early 2000s. So, the board asked him to come back and turn around his company. A little more than a year and a half later, the Charles Schwab Company reported record quarterly and annualized earnings in excess of $1.2 trillion in client assets. The turnaround was a success.

It would have been easy to blame the previous problems on market forces and to credit the turnaround to better management. However, much more was involved. At about the same time, Schwab was interviewed by Business 2.0 regarding how he could explain his success. Some of his answers reflected the type of results expected from using a Q-bank. In addition, some of his observations demonstrated an incisive understanding of the specific challenges he needed to overcome, much in the same way that a C-bank generates potential challenges.

His analysis indicated that the company’s financial slide was caused by more than market forces. Instead, he believed that the company had lost its emotional connection with its customers and did things to alienate them, such as increasing fees and losing the personal touch in marketing its products. The company also seemed to have lost the ability to generate customer referrals that, at one time, had been a cornerstone of its success. Morale was at an all-time low and pricing in the market seemed unfocused and made it difficult to retain new customers. Finally, Schwab’s cost structure became inflated, resulting in revenue paralysis.

Based on this analysis of the challenges facing the company, each challenge represents an explicit goal to help the company innovate and get back on track. For instance, by targeting specific areas, Schwab in effect created a C-bank of challenges such as:

•How might we reconnect emotionally with our customers?

•How might we reduce our fees?

•How might we increase the number of new customer referrals?

•How might we improve our pricing?

•How might we retain momentum with new customers?

•How might we retain more customers?

•How might we improve employee morale?

•How might we improve our cost structure?

•How might we streamline our cost structure?

All of these insights could have resulted from a Q-bank of stakeholders. In this case, it wasn’t necessary. However, assuming you don’t have this ability to hone in quickly on identifying priority challenges, there still is hope. The processes described in Chapter 2 and in this chapter provide a systematic, inclusive way—involving select stakeholders—to identify opportunities and to frame them as potential innovation challenges.

Everything done to this point, as part of a Q-bank, is designed to increase familiarity with the strategic challenges facing your organization, consider innovation obstacles and opportunities, and begin aligning key stakeholders with potential innovation targets. You now should have more clarity regarding your strategic terrain and some sense of priority with respect to areas requiring more innovative responses. Even if the results were as expected, the systematic exploration provided by the Q-bank will provide additional validation.

CHALLENGE BANKS (C-BANKS)

Once the client has approved the final list of responses from the Q-bank (Step #5, Figure 2-1 in Chapter 2), it is time to move on and conduct a C-bank of potential innovation challenge questions. The challenges are generated by using the responses to the Q-bank as stimuli. Each response is used as a potential trigger to generate an innovation challenge question, beginning with the words, “How might we . . . ?” This open-ended “invitation” to generate ideas helps to focus efforts toward a singular objective, yet encourages a diversity of responses.

C-banks can begin in one of two ways. First, a positioning statement can be presented to a group of stakeholders who are asked to use it to generate challenge statements and return them to a coordinator (Round #1). For instance, a manager might request challenges based on the following script:

As you know, we currently face competitive threats from emerging markets such as Brazil, Russia, India, and China. As we transition from a technology product to a service-based business model, what challenges should we address? For your responses, please put them in the form of, “How might we . . . ?” For example, “How might we improve human resources functions in emergent countries?” Please e-mail your responses to me no later than the end of the week. I then will collate everything and send you the results to stimulate additional challenges. Thanks for your help with this vital project.

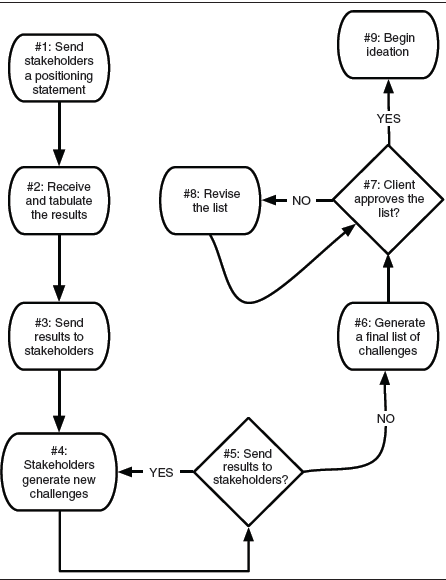

Figure 3-1 shows this version of a C-bank. The basic steps involved are described next.

The positioning statement helps participants understand the parameters involved by framing the key issues. Once stakeholders have a chance to generate additional challenges after inspecting the previous ones (Round #2), you can return the responses for a third round. The option also exists, of course, to conduct only one round without returning the results. Or, you could do only two rounds, organize those results into affinity groups, and send them to the client for approval and eventual ideation.

FIGURE 3-1. C-bank process using a positioning statement.

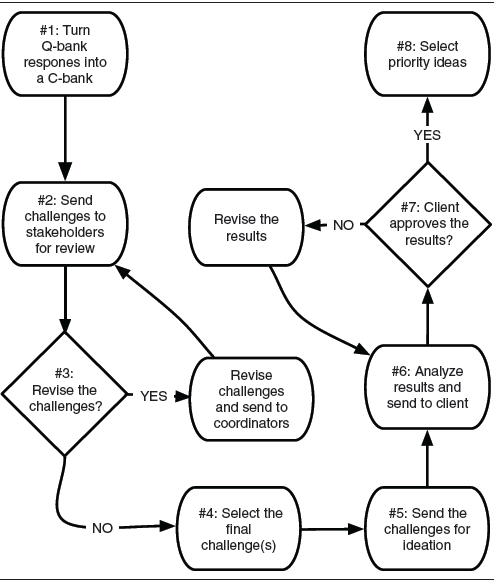

The second way to conduct a C-bank is to use the results from a Q-bank and generate a preliminary list of innovation challenges. You then could perform one or more rounds, each time organizing the results into affinity groups. Once the client approves the final challenge(s), ideation can begin.

This C-bank version is shown in Figure 3-2 and is described next.

1. Turn Q-Bank Responses into a C-Bank

Use responses from the Q-bank to help generate a list of challenges, grouped according to the original categories. Transforming stakeholder responses into challenges involves looking at each Q-bank question and response and using them to trigger potential challenge questions. In general, it is better to create too many challenges than too few. So, don’t worry if some may overlap each other.

It also doesn’t matter from which categories the challenges originate. This applies even if there is no logical connection between a Q-bank response and a C-bank challenge. For instance, consider a question from the “Products and Services” category listed in Chapter 2: “Do we know why [our products] have been unsuccessful?” One stakeholder response was, “No brand equity.” The resulting challenge might be: “How might we increase our brand equity?” This challenge now could be moved to the “Branding” category since the focus is no longer on products exclusively. It now is framed for possible ideation, which is more important than the category from which it was derived.

Sample Questions

The best way to illustrate this step is to use the examples in Step #3 for the Q-bank (Chapter 2). Based on the sample responses to selected questions from the Q-bank, some possible challenge statements are presented next. (Remember, not all of them may be derived directly from the original categories.)

FIGURE 3-2. C-bank process for framing innovation challenges.

Customers

1.How might we increase the number of wealthy customers?

2.How might we help potential customers qualify for our products and services?

3.How might we increase the number of qualified customers?

4.How might we increase the number of gift card users?

5.How might we help current customers to increase their credit ratings?

6.How might we encourage customers to increase their debt?

7.How might we increase customer access to our financial services?

8.How might we better meet customer expectations?

9.How might we improve our customer service?

10.How might we better understand our customers?

Financials

11.How might we increase the transparency of our fee structure?

12.How might we reduce our fees?

13.How might we eliminate our fees?

Branding

14.How might we increase our brand recognition?

15.How might we increase our brand equity?

16.How might we increase our aided brand awareness?

17.How might we increase our unaided brand awareness?

18.How might we better position ourselves in our customers’ minds?

19.How might we be perceived as the number one financial services provider in the world?

20.How might we brand ourselves as being the company for the ______ financial market?

Markets

21.How might we learn more about our current markets?

22.How might we learn more about new markets we want to enter?

23.How might we be more successful in our current markets?

24.How might we be successful in future markets we want to enter?

25.How might we communicate better with our markets?

26.How might we increase our competitive advantage?

27.How might we shift from single-product marketing to one-to-one marketing?

Goals

28.How might we best enter the South American market?

29.How might we solidify our presence in Western Europe?

30.How might we become more future-oriented?

Processes

31.How might we improve our infrastructure for servicing customers?

32.How might we become a more nimble organization?

33.How might we improve our public relations?

34.How might we increase our profitability for the next decade?

35.How might we become the number one financial services company in the world?

36.How might we achieve financial goals related to our target markets?

Products and Services

37.How might we better price our products and services?

38.How might we ensure high revolving balances?

39.How might we increase the perception that our products are priced fairly?

40.How might we develop new products faster?

41.How might we test new products faster?

42.How might we launch new products faster?

2. Send Challenges to Stakeholders for Review

This step is optional. If time or other resources are scarce, you might want to select the final one or two challenges from the previous list and move directly to Step #4, selecting the final challenge(s). Another reason to skip a stakeholder review might be if undue political issues are involved that might interfere with selecting priority challenges, collecting quality ideas, or otherwise disrupt the process. Thus, the project coordinators—usually internal managers and one or more external consultants—might revise the challenges using the criteria to be discussed in Chapter 4.

However, if time is available, consider sending the complete list of challenges to the stakeholders as is. Because they eventually will receive one or more challenges to use for idea generation, it can be useful to have them first review the master list of potential challenges, make revisions, and provide input on the priority challenges. A more refined and targeted product could result.

3. Do You Want to Revise the Challenges?

As noted previously, if stakeholders do not want to revise the challenges or cannot do so, or if there are other reasons not to revise (such as lack of time), move to Step #4. If the stakeholders choose to participate in revisions, ask them to evaluate the challenges by giving them the following instructions:

a.Read through all the challenges once to become familiar with them.

b.Go back through the challenges and look for ones that might be unclear or require editing or revising.

c.It is not mandatory, but try to see if any logical commonalities exist between or within the categories. If so, organize them into affinity groups that might become new categories or subgroups of existing categories.

d.Select the priority challenges and create a list of your top three to five preferences.

e.Please feel free to add any comments you might care to make.

Before starting revisions, however, emphasize that the purpose of this activity is to evaluate the challenges and not to generate ideas—that will be the next activity. Suggest that if they think of any ideas while revising the challenges, they should write them down and save them for Step #5, which is idea generation.

Once the stakeholders have finished revising and adding any comments about the challenges, they should return them to the coordinators. The coordinators then should review all of the changes and revise the list of challenges as deemed appropriate. Then, the coordinators should send the revisions back to the stakeholders (Step #2) for any additional revisions, based on the input from others. This input can increase the quality of the list of challenges and sometimes, more important, increase the amount of stakeholder buy-in with respect to the overall project. (Even though only one or a small number of challenges will be used, the remaining ones can be retained for later idea generation.) Finally, review the second round of revisions, make any changes, and decide if you want to use one final round or move directly to idea generation.

4. Select the Final Challenge

Depending on how well the challenges were framed, selecting the final challenge (or challenges) could be a difficult process. The first decision is to determine if the C-bank statements were relatively “clean” overall. In this case, a clean challenge is one that conforms to the seven evaluation criteria listed here (which will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 4):

1.Begins with the phrase, “How might we . . . ?

2.Singularity of objectives?

3.Absence of evaluative criteria?

5.Appropriate level of abstraction?

6.Appropriate use of positioning elements?

7.Clear and unambiguous?

Next, the selection process should focus on assessing differences among any new challenges submitted. This involves looking for duplicates and possibly rewriting some challenges for clarity, if necessary. You must exercise some caution, however, to avoid deleting a challenge that is only a slight variation instead of a duplicate. Also, the same caution must be used when rewriting for clarity.

Finally, one or more client representatives may need to approve the final challenge or challenges. One way to facilitate this process is for the coordinators to create a list of priority challenges that are grouped by commonalities. In information theory, this is known as chunking, meaning that it is easier to evaluate a small number of clusters of alternatives than a large number of individual ones. For instance, choices might be made on a group of challenges pertaining to branding and another group to internal processes, as opposed to rating all the individual challenges within these categories. Thus, the choice becomes a simpler one of selecting from between rather than within groups or categories. Of course, this process can be as detailed or as general as desired. (This process will be discussed in Chapter 11.)

5. Send the Final List of Challenges for Ideation

People who participate in idea generation for challenges typically include some or all of the stakeholders used to generate the list of challenges. However, it is usually better to involve a broader group in idea generation. Different perspectives and knowledge bases from participants outside the organization can provide a more creative and richer set of potential challenge solutions.

When you send the challenges, always remind the recipients that they should defer all judgment when generating their ideas. This is the most important of all idea generation principles. It is probably also the most violated principle in everyday brainstorming, despite its emphasis in business literature for the past seventy years. And, more important, such behavior persists in the face of numerous empirical research studies verifying the value of deferred judgment on idea quantity during group brainstorming.

For instance, small groups on reality television shows such as The Apprentice typically demonstrate an alarming lack of practice in applying this principle. Instead, the teams of wannabe apprentices more often than not use a sequential process of generate-evaluate-generate-evaluate, et cetera. Each idea is given one chance to survive and then is eliminated immediately if there is not unanimous approval. People whose ideas are rejected so quickly often become disillusioned with the process and are more reluctant to suggest anything new, especially ideas that might differ from the prevailing direction of the rest of the group. The result is a negative group climate that is not conducive to innovative thinking. As Alex Osborn, the father of brainstorming, used to say, “It is much easier to tame down a wild idea than to tame up one.”1

For readers who may not be aware of the disadvantages of failing to defer judgment, the answer is relatively simple: Ideas are the raw material of solutions. Ideas should be viewed merely as triggers to help stimulate solutions that can be applied to resolve challenges. Viewed this way, every idea at least has minimal potential to spark other ideas or modifications. Moreover, the more ideas generated (regardless of their quality), the greater the odds of coming up with at least one plausible solution; toss ideas away quickly, and you lose the power of their numbers and stimulation value. Remember, there will be an opportunity to judge all the ideas, so you can choose when that will be.

As with the Q-banks, you probably should conduct at least two rounds of idea generation. So, resend the ideas, but do not alter the wording in any way, even if they are not clear to you or contain criteria or reflect biases. Such things can be removed during the final evaluation. It is more important to preserve the original intent of the persons who generated the ideas.

6. Analyze the Results and Send to the Client

Once the rounds have been completed and the project coordinators have received the final list of ideas, their first task is to remove duplicates. Again, be careful to ensure that duplicates are just that and nothing more. Even minor differences in wording can alter semantics and how others interpret meanings. If there is any doubt at all about an idea being a duplicate, keep it on the list.

Next, look for affinity groups and organize the ideas into clusters of commonality. As discussed previously, the original categories typically provide the structure needed for such groups. However, now is the time to see if there are enough “outliers” within a category—that is, ideas that do not fit that category cleanly, but seem to have commonalities—to justify creating a new category for them. A few ideas generated across multiple categories might be better listed under a different or a new category. So be sure to scrutinize all the ideas for their appropriateness of “fit” within the categories.

You also should try to assign some priority to the ideas. There are at least three ways to do this. First, if time is available and it is important to get stakeholder buy-in, you might solicit the stakeholders’ input by having them rate all the ideas on preestablished criteria (see Chapter 11). A second way is to involve only key stakeholders and/or outside people, even if they did not participate in the idea generation process. A third option is simply a combination of the first two: Involve some or all of the idea generators and also some outside personnel who originally were not part of the C-bank process.

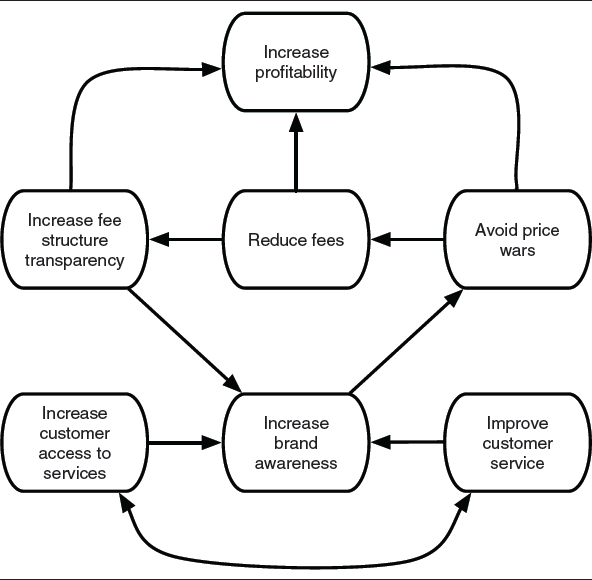

Finally, if several challenges seem to be interrelated and dependent on each other, you might consider constructing a conceptual map to illustrate the possible connections. For instance, consider the following challenges from the previous C-bank (numbers in parentheses refer to the specific challenges listed previously):

a.How might we increase our brand awareness? (#16)

b.How might we increase the transparency of our fee structure? (#11)

c.How might we reduce our fees? (#12)

d.How might we improve our customer service? (#9)

e.How might we increase customer access to our financial services? (#7)

If more clarity is needed, a concept map, such as the one shown in Figure 3-3, also can be developed depicting how these objectives might be interrelated. Otherwise, such maps can be created after finishing a C-bank. A major advantage of these maps is their ability to help users identify priorities in terms of which challenges should be attacked first and how some might be either subordinate or superordinate to others.

That is, some relatively specific challenges should be resolved before working on broader ones; or, broader ones might be best dealt with directly if the subordinate challenges are not perceived as being in a causal relationship. For instance, in Figure 3-3, the broadest challenge is to increase profitability. In this hypothetical situation, the map suggests that reducing fees is one way to do this, presumably based on the assumption that lower fees will drive higher sales volume and, hence, profit. (A more detailed description of strategy maps is provided in Chapter 5.)

FIGURE 3-3. Hypothetical interrelationships among innovation challenges.

Once you are satisfied with the results and have organized them satisfactorily, you may send them to the client for final approval, the next step in the C-bank process.

7. Client Approves the Results?

Sometimes, the client already has been involved in processing and analyzing the final list of ideas. This is a matter of available time and personal preference. Some managers obviously feel a greater need to “ride herd” on a project than others, depending on their perceptions of how important the project is, the risks to them if the outcome is not acceptable to higher-ups, and their idiosyncratic need to monitor all activities—or to micromanage in some cases! Of course, if the client does not approve the results, you must revise them and resubmit for approval.

8. Select the Priority Ideas

The final evaluation and selection of the C-bank ideas should be an exhaustive, systematic, inclusive, decision process involving all important stakeholders. This process is detailed further in Chapter 11, so only a few comments will be made here. Perhaps the most important consideration—especially when working with a group—is to begin with a relatively long list of explicit evaluation criteria. As with idea generation, criteria evaluation also should be a process involving deferred judgment. List all possible criteria first before starting decision making. If there is an extensive list of criteria, you can group items into common categories. Finally, if you have a lengthy list of ideas to narrow down, consider creating screens to filter ideas—that is, an idea must satisfy one or more criteria to pass to the next level.

NOTE

1.Alex F. Osborn, Applied Imagination, 3rd ed. (New York: Scribner, 1963).