ONE

Framing Innovation Framing:

An Overview

We are creatures of habit. We sometimes resist change just because it is change. It is easier just to stay within our comfort zones.

“THAT’S THE WAY WE’VE ALWAYS DONE IT!”

What company wouldn’t want to reduce its costs, save its customers time, and increase its customer satisfaction, all while growing its business? Well, it turns out that many companies act as if they do not! Instead, they keep doing things the way they always have, even though that might not work for them or their customers. They do it because that’s the way they always have done it. And, perhaps, because that is how other companies in their industry have always done it. We are creatures of habit. When an employee asks why something can’t be done, the patented response often is: “Because that’s how we’ve always done things!” It is difficult to argue with logic like that!

Where has all the innovation gone? It has disappeared into black holes of fear and uncertainty, swirling and meandering about, seemingly without bounds. It has been reigned in, flipped over, tied up, and wrapped into neat little packages of meaning that present happy corporate faces to the outside world, while struggling and suffering internally and for shareholders. It has disappeared in some companies that seem locked into conventional ways of doing business, in spite of undesirable results. Just as some people seem to persist in behaviors that produce unproductive outcomes, so do some organizations. It is as if they cannot help themselves.

These companies lock themselves into self-created perceptual “frames” that prevent them from innovating. There is a certain degree of comfort in operating within familiar, comfortable frames. Such frames reduce uncertainty by establishing known boundaries that also help to create meaning for us and, therefore, become our realities. Yet, it is this same sense of knowledge and meaning that presents the biggest obstacles to change and innovation.

“LET’S TRY SOMETHING DIFFERENT!”

The fact is that companies can help themselves, but they first must make a conscious choice to change the status quo. This is exactly what more companies now are choosing to do. For instance, Fujitsu decided to do away with the accepted industry model of customer service. Although the company wants to reduce costs, save its customers time, increase customer service, and achieve growth, it figured out that things would have to change—that it would have to reframe the conventional model of doing business in its industry.

James Womack, author of Lean Solutions: How Companies and Customers Can Create Value and Wealth Together, notes that Fujitsu figured out a win-win way to change the conventional model of customer help lines. This part of customer relationship management (CRM) represents one of the outsourced business processes that have been the subject of increased attention in recent years. As used by most companies, help lines seem to stand between companies and their customers. For some companies, help lines appear to serve as the means to get rid of customers instead of retaining and acquiring new ones. The traditional help line frame is one in which operators are paid a flat rate for every complaint they handle. The faster they can get a customer off the line, the more money the operators can make and the higher the margins for the companies. So, the incentive is very clear for operators: The more customer complaints you field, the more money you will make.

One thing left out of this equation is the lack of any incentive to reduce the actual number of complaints. After all, wouldn’t such a frame be counterproductive? Fujitsu analyzed this model and decided that most customers would rather not need to call a help line at all. An astonishing conclusion, isn’t it!

So, the company contacted its customers (Telcom and large computer providers) and told them that it would rather be paid by the potential number of complaints instead of the number actually handled. And, Fujitsu said that it would prefer to focus on the vendors’ problems than those of the vendors’ customers. In other words, the company wanted to learn why customers even called and then figure out a way to eliminate the need to do so altogether.

Fujitsu reframed customer service by training representatives to work with customers to determine why their problems arose and who would be the best people to resolve them. In addition, the company decided to create a positive experience by using its help lines to tell customers about product features they might not be aware of or to ask them what else they would like in a product or service. One immediate result was many new product ideas. And new ideas, of course, often translate into innovation and higher profit margins.

Now, if you proposed this model to some managers, they immediately would point out how much more expensive this approach would be. (Besides, if they haven’t been doing things that way, then how could it even be considered!) What they might overlook, however, is the potential long-term impact on the bottom line. In the case of Fujitsu, costs gradually decreased as the number of calls declined. The turnover of service reps was only about 8 percent, compared with an industry average of around 40 percent. So, the company saved consumers time, increased customer satisfaction, reduced costs, and increased the company’s growth rate—all by reframing the conventional model.

THE PARADOX OF PARADOX

One thing Fijitsu did was to employ paradox to redefine a basic business process. This seems to be a characteristic of many organizations perceived as being innovative: When faced with challenges, they have the ability to reframe them into new, more productive and innovative ones. In essence, they have learned the power of testing all assumptions, including even the relatively simple and trivial ones often taken for granted. As Douglas Adams, the creator of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Universe, said: “The hardest assumption to challenge is the one you don’t even know you’re making.”

A paradox can be defined roughly as any statement that appears to be true while also having the ability to be false—in other words, a contradiction. Seemingly contradictory statements have been the basis for much inventive thinking. (In fact, an entire industry based on perceptual contradictions has been developed based on TRIZ—a Russian acronym known as the Theory of Inventive Problem Solving.) Contradictions help us test any assumptions we make, especially with respect to conventional thought patterns. For instance, consider what has been accepted as true in the automobile insurance industry: high prices, mediocre service, and complex bureaucratic procedures. This was the norm until Ohio-based Progressive Casualty Insurance Company tested these assumptions.

Instead of doing business in lockstep with the major companies, Progressive CEO Peter Lewis noted that the company would do things differently and offer faster claims adjustments, work on weekends, and—gasp!—offer price comparisons with its competition! Although the auto insurance industry had been in the red over the last five or so years, Progressive increased its revenue more than 36 percent—a rate six times that of the industry.

Other examples of frame busting abound in academic and popular literature.

•When Steve Jobs returned to Apple Computer as it was spiraling downward, he started using the tagline, “Think Different!” [sic] and then tested assumptions about what a computer was supposed to look like. More recently, he illustrated the power of reframes by completely upending the traditional model of how music is sold. With iTunes, consumers now can download music, videos of television shows, and movies.

•Michael Dell of Dell Computer contradicted the old frame of computers being high tech, involving expensive research and development (R&D), and being high-margin products sold in stores. Among other things, he created the market leader in online sales of laptops that were sold directly to the consumer, instead of through a third-party vendor, with an emphasis on volume and purchasing efficiency.

•Plantronics tested convention by increasing collaboration between engineers and designers. Instead of designers having to create products after engineers produced the technology, management decided to involve the designers throughout the process. This way, designers no longer needed to focus on how to overcome technical obstacles and could devote their attention to meeting consumer needs. The result was a 31 percent return on invested capital.

•In a now infamous decision, Coca-Cola executives decided to rebrand Coke as a sweeter beverage known as New Coke. Based on blindfolded consumer focus groups who compared sips of old and new coke, the company concluded that consumers would prefer New Coke and then launched it, with disastrous results. Coca-Cola then reframed its perceptions and retreated by bringing back Classic Coke. So, it initially appeared that consumers preferred a sweeter drink, but the contradiction was that they also did not prefer a sweeter beverage. This contradiction arose because the market tests did not reflect how people actually drink Coke: They don’t wear blindfolds and they take more than one sip. Thus, they liked it but they didn’t like it—a logical contradiction!

•In the early 2000s, McDonald’s Corporation realized that its previous, successful frame of “one size fits all” was no longer effective as consumers began demanding healthier foods. By recognizing consumer trends in this area and reemphasizing service, McDonald’s experienced a 10 percent increase in in-store sales in the first half of 2004 and an 11 percent decrease in complaints.

•A few years ago, Sirkorsky Aircraft Company was asked to bid on a contract for the Air Force One presidential helicopter, a contract the company had held for about fifty years at the time. Any business relationship that has lasted that long constitutes a frame about future expectations. Perhaps the company used thinking such as, “We’ve had our contract renewed over half a century and we’ll always have it.” The company also might have assumed that its product’s features would remain constant and viable as seen by its customers—for example, helicopter size, time to market, and communications technology. In fact, the Sirkorsky president at the time supposedly said he would jump out of a flying helicopter if the company didn’t get the contract. Instead, the Lockheed Martin Corporation won a six-year, $6.1 billion contract. (No word yet on the helicopter jumping!)

IDEAS IN SEARCH OF PROBLEMS

Many organizations practice what I call “horse-before-the-cart innovation.” They rush into generating ideas on how to become more innovative before they clearly have identified and articulated the most productive challenges. We have been trained and conditioned to gloss over the specifics of our challenges. As a result, we often make implicit assumptions as to the exact nature of our challenges and their priority with respect to other challenges. And then we jump right into generating ideas.

Most of us tend to be more solution minded than problem minded, as industrial psychologist Norman R. Maier used to note. Although lip service may be given about the need to “define the problem,” relatively few people do it well. The very best ideas to the most poorly defined problem might as well not even exist. Anyone can have an exciting brainstorming session with hundreds of ideas. Frequently neglected, however, is devoting as much time and attention to clearly defining a “presented” challenge as is given to idea generation. As famed photographer Ansel Adams said, “There is nothing worse than a brilliant image of a fuzzy concept.”1

Creativity consultant and business professor Chris Barlow, in discussing the role of redefining problems for brainstorming, observes that idea quantity is more likely when “deliberate divergence” is used as a way to define problems. That is, defining problems should have far greater priority than we give it in relation to generating ideas. The ideas will come if we first consider more options for problem definitions.2

We frequently expend a lot of time and energy using our creativity to generate ideas when we first should devote that time and energy to generating challenge statements to guide ideation. Instead, we often assume that we know what the problem is and just dive into brainstorming sessions. Why? Because that is what we have learned from experience and conditioning. It doesn’t matter if research shows that we can generate significantly more ideas by taking the time to define a challenge and then deferring judgment during idea generation. What appear to matter more are the choices we make to persist in doing the same things the same ways we always have done them!

As a result, what often happens in a lot of brainstorming sessions is that ideas are tossed out that do not seem to make sense. The reason is not always that they are bad ideas; rather, the ideas different people think of may be based on varying assumptions as to what the “real” challenge is. Perhaps you have been in such a session where—after generating ideas for a while—someone says something like, “So, now exactly what is our problem?” Even groups that start with apparently explicit challenges may choose one so ambiguous as to complicate things even further. You just can’t expect to generate useful ideas if you don’t start with a clear-cut challenge question.

Undoubtedly, many organizations also may use such an approach to innovation initiatives. For instance, corporate managers often frame challenges based mostly on broad, strategic outcome objectives—for example, profitability or market share—along with some secondary goals such as generating new products and enhancing marketing and branding.

The best route to achieving any of these objectives is not to merely generate ideas but to first construct tactical maps to lay out the strategic terrain for all objectives. The old saying still holds true: “If you don’t know where you want to go, any road will take you there.” It also is true that even if you think you know where you want to go—an often costly, unchallenged assumption—you must create a map of goals to achieve along the way. These maps frequently are based on the premise that the objectives are stated clearly, known, and understood—often an erroneous assumption.

Most organizations do a good job of collecting research on how and where to innovate. However, Doblin, Inc. estimated in late 2005 that only about 4.5 percent of innovation initiatives succeed! One reason might be due to poorly framed innovation challenges. Unfortunately, there still are few resources on how to frame challenges for ideation. Before looking at the process of framing challenges, however, it is important to think first about the general concept of perceptual framing.

“FRAMING” FRAMING

When you have finished reading this sentence, you will have been “framed.” The sentence conveyed some form of meaning to you by creating intentional or unintentional cognitive boundaries. What you understood at the time is what you chose to think. What you understand now may be completely different because this additional information created a potential “reframe” for you. And, right now, your frame may be different again, ad infinitum.

There is a considerable amount of research on framing, most of which deals with how frames can be used to send messages designed to influence others. According to Schoemaker and Russo, there are the following three types of frames:

1.Problem frames used to generate ideas

2.Decision frames to make choices

3.Thinking frames involving deep mental structures and prior experience

This book will focus on problem frames as they are used to clarify strategic challenges for generating ideas and creating innovative solutions to organizational challenges.

Failing to devote attention to how we frame innovation is a failure to test assumptions and, more than likely, adopt less than optimal perceptual frames. How we see and define things determines how we behave. If we do a less-than-adequate job of framing a problematic situation, we are less likely to resolve it. Thus, the more we understand about the general nature of frames, the better challenge solvers we will become.

According to Robert M. Entman, professor and head of communication at North Carolina State University, “To frame is to select some aspects of perceived reality and make them more salient in the communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation and/or treatment recommendation for the item described.”3 According to Russo and Schoemaker, frames in the context of management are “mental structures that simplify and guide our understanding of complex reality—[and] force us to view the world from a particular and limited perspective.”4

My definition of a frame aligns partially with these two. I define frames as “experience-based sets of cognitive boundaries we construct that define a given situation and create meaning.” A perceptual frame is a fluid, dynamic, ever-evolving boundary of meaning, inference, and assumptions. As it morphs, twists, and turns, it alters our perceptions of what we have experienced, what we are experiencing at a given time, and shapes the assumptions we make. Thus, a frame is our reality at any given moment. It also can determine how we are likely to view similar situations in the future.

Frames help us to understand and to focus our thinking, thereby reducing uncertainty and enhancing human communication. Framing also is an exclusionary process in which we consciously or subconsciously include or emphasize some information at the expense of other information. That is, an ideal framing process helps us to deconstruct perceived ambiguous situations and clarify and create focus so we can achieve our objectives—especially our strategic ones.

There is a lot of research on how people will perceive identical situations differently, depending on how they are framed. For instance, research suggests that people given a preference for meat that was 75 percent lean versus meat that was 25 percent fat invariably chose the former, even though the choices were identical! This reaction describes how people often tend to assign more importance to negative information than positive. Such frames also have been found to attract more attention. Another type of perceptual framing involves attempts to persuade others to think a certain way or do certain things. Political advertising and public relations are two common examples of this type of framing.

Most attempts at classifying frames represent prescriptive or persuasive framing in that there is a conscious intention to get us to align our thinking with a specific point of view—to tell us how we should think. Persuasive framing, however, is not the only kind. There also is descriptive framing (also known as “semantic framing”), although it receives much less attention than the persuasive variety. In descriptive framing, the only intention is to clarify and make salient specific components of a challenge so that it might be resolved more easily. Descriptive framing, in contrast, attempts to generate alternate phrasing terms. Thus, the framing process involves describing what is instead of what should be.

Clarification of current and desired perceptual states, along with how to close the gap between the two, is the basis of all problem solving. Challenges are created when we perceive a gap between these states; challenge solving, then, is the process we then use to make the is like the should be—that is, we make a conscious attempt to transform an existing state into an ideal one using innovative means. So, if you are dissatisfied with your current error rate in processing customer claims—thus, believing it to be less than you desire—you would resolve this challenge by using activities to close the gap.

The ultimate goal of innovation framing is to state a challenge in such a way that it will produce the most innovative, optimal results. In this instance, there is no intention to persuade someone how to think; rather, the focus is on clarifying some desired innovation challenge involving perceptions of current and desired states. Another example would be increasing brand awareness about a new line of products. By implication, the brand awareness currently is lower than desired; the desired level then would be some predetermined level of measurable awareness. In this case, the frame might be stated as: “How might we increase the brand awareness of our X line of new products?” (Measurement of the degree of change would be an evaluation criterion and should not be part of the challenge. This concept will be discussed more fully in Chapter 4.)

Such a statement is relatively simple and direct, it doesn’t obscure intent with criteria, and it clearly identifies the objective. Contrast the statement with the following modified real-life example from a major, global corporation: “How might we create state-of-the-art solutions to ongoing attacks that jeopardize endangered species more than other attacks while satisfying key stakeholders?” Or this one from a large government organization: “How might we create a new product/service/process or an enhancement to an existing product/service/process that will increase revenue involving current/new customers and may involve developing new marketing/partnership opportunities?” Both of these statements are overly complicated, ambiguous and contain unnecessary and confusing criteria. The need, then, is to deconstruct them so that they can be used for productive idea generation and achieve strategic objectives.

THE IMPORTANCE OF FRAMING INNOVATION

STRATEGICALLY

Although most companies invest heavily in R&D, the effects on bottom-line innovation are questionable. As noted previously, the success rate of innovation initiatives across all industries is only 4.5 percent. It is unlikely that this low rate is due to a lack of innovation processes or access to intellectual capital. Instead, poorly framed innovation challenges might contribute toward this low success rate.

The August 2005 issue of Training & Development magazine published an article on “Strategy Blockers”5 as seen by executives, vice presidents or managers, and directors. They were asked, “What gets in the way of strategy execution for top leaders?” The most frequent obstacle was “the past and habits” (35 percent). This seems to imply that rigid perceptual frames can block the execution of strategic plans.

A failure to frame and reframe strategically undoubtedly has multiple causes, such as inaccurate market data, tradition, the organizational culture, market uncertainties, managerial apathy, or an inability to multitask in a rapidly changing environment. Sometimes we are so busy that it’s just easier to do nothing and stay on the original course, assuming the best will happen. Thus, we may keep cranking out ideas to maintain the current strategic direction without considering if the direction is correct.

It also is possible, however, that one cause may be the inability to ask the right questions. As nineteenth-century author G. K. Chesterton noted, “It isn’t that they can’t see the solution. It is that they can’t see the problem.” It very well may be that innovation fails far more often due to faulty problem framing than faulty idea generation or execution. Most of us have been conditioned to accept a problem as given and immediately jump into a search for solutions.

Renowned management theorist Ian Mitroff notes that it is better to solve the right problem incorrectly than the wrong problem correctly. At least you would be working toward the “correct” end state. And, in an article from Innovation Tools electronic newsletter, Imaginatik CEO, Mark Turrell, observes that in companies with large revenue growth gaps, it is especially important that they “invest effort before the front-end stage of innovation to identify opportunities and frame their initiatives”6 (italics added).

The strategic challenges top management devises guide ideation and implementation. Starting in the wrong direction almost guarantees failure. Too often, however, we tend to assume we know what the “real” problem is without testing all the potential assumptions involved. Business 2.0 magazine asked management guru Peter Drucker, “What is it that executives never seem to learn?” His reply was that “. . . one does not begin with answers. One begins by asking, ‘What are our questions?’”7 With a focus on ideas, many managers are more likely to lock onto the first problem definition and stick with it, often with disappointing results.

It is very easy to acknowledge this, but very difficult to take the time to frame challenges carefully. Getting to Innovation will help structure the questioning process and make it easier to design strategic innovation frameworks. A review of unsuccessful business frames reveals symptoms of an underlying inability to test assumptions and knowledge of how to frame situations productively—and competitively. Numerous examples exist of how some companies are able to reframe a market and become more competitive. Some of those companies have been described previously in this chapter, but here a few more:

As noted previously, when Michael Dell started his computer company, the prevailing frame was that computers were high tech, involved expensive R&D, and were high-margin, low-volume products. He reframed these assumptions by using low-tech, minimal R&D, and low-margin but high-volume products. He also took advantage of Internet-only sales and soon captured market share for personal computers.

Even strategic frames that were previously successful need tweaking as conditions change. For instance, in the past decade, General Electric’s growth under Jack Welch was reported as 5 percent based on a strategic focus on cost cutting, increased efficiency, continuous improvement, and similar performance-based objectives. Under new CEO Jeffy Immelt, GE’s profits grew by 24 percent based, in part, on the concept of reframing the company’s energy business model from gas turbines to wind and solar power. Also consider IBM, once the IT technological leader. It now is embarking on a new frame involving a transition from technology to being the leader in business process outsourcing. So, it is just as important to identify frames that do not work as it is frames that do.

Perhaps the most compelling case for framing innovation was made by IBM CEO Samuel J. Palmisano in an interview with Business Week magazine about an IBM survey of CEOs of top companies and government leaders. A focus on business model innovation was at the top of the list of concerns by the respondents. According to Palmisano, an increasingly competitive environment increases the need to identify and deal with challenges in business models. In fact, he notes that such challenges can help jump-start organizational innovation. Technological advances, such as infinite computing capacity, have created new opportunities to address new challenges. For instance, IBM now is trying to become more global, pushing down decision making, and trying to develop new ways to collaborate with external groups. Thus, a major challenge is how to foster such collaboration within an organization and between it and other organizations.

None of this should be surprising to observers of corporate performance. Yet, the struggle continues for organizations to achieve corporate objectives, to increase market share and shareholder value, and to defend the bottom line in a complex and changing environment. The answer put forth by this book is not more ideas. The answer, instead, is more questions—especially the right questions, and how to generate and fit them together into meaningful, conceptual frameworks.

This book is designed to serve as a user’s guide for testing organizational assumptions and molding the results into clearly articulated networks of tactical and strategic recipes for creating value in organizations.

INNOVATION STRATEGY VS. TACTICS

In many ways, organizations are just like the individuals who work for them. For instance, in order to change, both must understand where they are, where they want to go, and how to get there. That is, they both must solve problems as discussed previously. Perhaps more important, they need to know why they want to get there. And, just as with individuals, organizations must have a strong impetus for change—a “felt need.”

Any form of change requires a plan—a strategic plan—focused on the direction and type of change. This is an interesting dilemma because organizations often take the road they think is best. However, this road may be a dead end because they haven’t done their due diligence to determine if it is the right road for them at that time. Or, they haven’t properly diagnosed an issue and, instead, go with an intuitive decision leading to faulty outcomes.

Ideally, the is (the current state) and the should be (the desired state) will be identical; pragmatically, there may be discrepancies between the two as well as disagreements on how to close the gap. When a gap is perceived as being closed, then a challenge has been resolved. Of course, this assumes that these perceptions are in fact correct.

One way to resolve differences in perceptions is to focus on answering the “why?” question. Organizations, as with individuals, must be able to justify changing their strategic directions. Why do they want to stay on a certain course? Why would they want to change? In organizations, however, such justifications can be acutely difficult, considering all the complexities and uncertainties involved. The answers are never easy, but there never will be answers without proper questioning.

Strategic planning at the most hypothetical and basic level is relatively simple: It is just basic problem solving involving the transformation of perceived, current situations into perceived, desired goal states. Of course, strategy is also a lot more complicated. That is one paradox of process change: simple yet complex; complex yet simple. It all depends on how you frame it.

Strategic Objectives

Creating a strategy involves identifying strategic objectives—the activities that must be undertaken to achieve the overall strategy. The specific nature of these objectives is wholly dependent on an organization’s mission and vision. That is, an organization’s high-level, strategic objectives must be aligned with an overarching vision. Unfortunately, some CEOs read about the latest business or management fad and tell their people to implement it without considering their missions and visions.

Some sample strategic objectives include:

•Increasing profitability and shareholder value

•Increasing return on investment and size of market share

•Meeting customer needs

•Elevating the quality of customer service

•Improving product or service quality

•Enhancing growth rates

Depending on the situation, achieving each of these may require separate processes or multiple, coordinated processes of the transformations involved in turning current states into desired states.

However, it is not always a simple matter of making progress toward objectives. Many organizations may appear to have different priorities for different objectives. (Some senior leadership also may have different priorities, thus further complicating the mix.) For instance, profitability may be seen as being more important than customer service. Moreover, one objective (for example, customer service) may be perceived as functionally subordinate—that is, secondary—to another, such as profitability. Thus, one or more subordinate objectives, such as customer service, may need to be achieved before achieving one or more superordinate—that is, primary—objectives, such as profitability.

Tactics

Strategy provides the overall direction while tactics help to ensure progress along the way. In this case, a tactic is defined as a means to achieve specific objectives. Multiple tactics may be required to achieve one objective. The tactics used to achieve this objective may be the same, similar, or different from tactics used to achieve other objectives. And, progress about a strategy can be determined by the degree to which each tactical objective is achieved.

Strategy

A strategy consists of a series of tactical actions all oriented toward obtaining a strategic objective. Each tactical action has a specific objective that when added to other tactical actions will help achieve strategic objectives. Tactics exist only in dependence with strategic objectives. That is, they are employed for the primary purpose of achieving a desired goal state. They are not independent in that they are implemented within the framework of a larger, superordinate or primary goal in mind—for example, a core strategic objective such as profitability or shareholder return.

A good strategy should provide a big-picture vision of an organization. As Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein noted, “Don’t get involved in partial problems, but always take flight to where there is a free view over the whole single great problem, even if this view is still not a clear one.”8 The ultimate goal is attaining one or more primary objectives. Sometimes this is done best by achieving a series of lower-priority, less abstract secondary objectives.

INITIATING STRATEGIC DECISION MAKING

Research on organizational decision making indicates that most innovation initiatives are prompted by stakeholder “activists” who call attention to challenges facing their organizations. These stakeholders draw attention to issues requiring organizational awareness. Decision makers then must decide what, if any, action might be warranted. If it is decided that some action should be taken, a decision then is made to apply either a quick fix or a more innovative approach. For instance, if it is determined that the company’s stock price is declining, top management members can determine the validity of stakeholder claims and act accordingly.

Stakeholders frame their perceptions in ways to convince management that some degree of attention is warranted, if only to justify paying attention and investigating a potential challenge in more depth. As a result, how successful they are in persuading management to pay attention to a challenge will depend on how they frame the challenge. Moreover, these frames may dictate the action taken to deal with challenges. One frame, for instance, might result in a decision to benchmark a potential threat or opportunity; others might trigger efforts to create innovative responses. To make such distinctions, some research suggests that organizational decision makers tend to rely on networks of key stakeholders for identifying needs and how to deal with them.

Innovation Frames

Once needs are recognized, organizations are supposed to act based on their strategic visions and planning processes. When they decide to innovate, they create strategic innovation frames to guide the innovation process. A primary obstacle, however, is how to state innovation challenges and link together objectives so that they will produce the strategic results desired.

Many organizations have a primary objective of achieving, sustaining, or increasing profitability. Achieving this objective, however, is not as simple as asking, “How might we achieve/sustain/increase profitability?” This challenge fails to incorporate other secondary objectives that could (and should) be linked together to increase profitability. In this case, secondary objectives are those that must be achieved before others can be. Conversely, primary objectives are those at a higher level of abstraction than subordinate objectives and are attained only by reaching one or more subordinate objectives.

For instance, from reading an analysis in Business Week of aerospace giant Boeing Company,9 the company’s challenges might be described as:

•Restoring the company’s tarnished image

•Squeezing more profit out of existing businesses

•Increasing revenue

•Improving a toxic corporate culture

•Reducing bureaucracy

•Encouraging innovation

•Increasing financial growth

Each of these challenges could function as a single corporate objective worthy of innovative solutions. However, the question is: “How should these objectives be framed and linked together in the most productive way?” This is where framing strategic innovation can help.

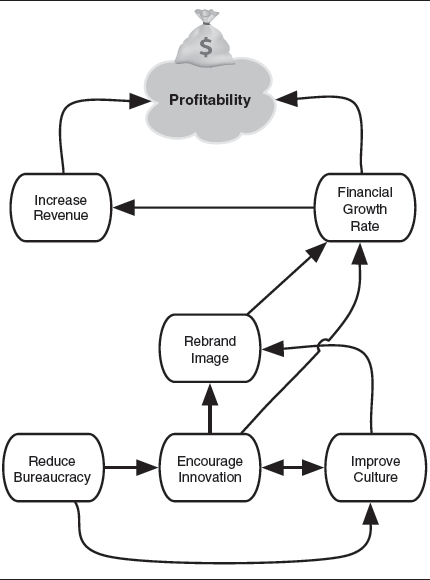

Consider the conceptual map presented in Figure 1-1. These relationships illustrate that strategies are complex, interrelated decisions. Most objectives are nested within hierarchies of other, related objectives and multiple goals typically must be achieved to accomplish one primary goal. Once semantic, perceptual framing is placed in the context of organizations and their strategies, things can become quite complex.

As shown in Figure 1-1, there may be clusters of objectives linked together by commonalities. These clusters can exist at the same or on different levels. Also, they might be linked with other clusters within a hierarchical level or between levels. Moreover, not all objectives in a cluster may be linked across levels. For instance, Figure 1-1 shows encouraging innovation at the fourth level linked with financial growth rate at the second level. How these objectives are linked may depend on a variety of factors, especially the competitive environment within different industries.

FIGURE 1-1. Boeing Company hypothetical challenge map.

Conceptual Framing Maps

Visual diagrams of knowledge and organizational strategy have been around for some time, especially from the perspective of cognitive mapping. For instance, most cognitive strategy maps draw on what is known as personal construct theory. It suggests that we understand our environments by organizing concepts that are relevant to a specific environment. Some researchers who interviewed senior managers in the grocery store industry observed that they tended to create hierarchies of their competitive environments based on degrees of abstraction. That is, some environments are seen as broader and more encompassing than others. For instance, increasing profit might be viewed as more abstract than reducing employee absenteeism.

To some extent, Figure 1-1 parallels the more encompassing and elaborated strategy mapping process used with the balanced scorecard (BSC) approach of business strategy consultants Kaplan and Norton. They maintain that traditional strategic planning is based too much on historical financial data and not enough on the intangibles present in corporations. To increase performance, organizations first should create a strategy map consisting of the following four value-creating processes or perspectives:

1.Financial

2.Customer

3.Internal processes

4.Learning/growth

These maps then are used to translate an organization’s vision and mission statements into effective performance. Basic strategy maps can involve thirty or more components, all of which must be aligned with each other and monitored over time.

The hypothetical Boeing objectives shown in Figure 1-1 correspond roughly with the top three BSC perspectives. Thus, “Profitability,” “Increase Revenue,” and “Financial Growth Rate” represent financial perspectives involving long-term shareholder value. (These also might be labeled as high-level, primary objectives.) Next is the customer perspective of rebranding the corporate image. This would be subordinate to the financial perspective because rebranding could help increase the financial growth rate. Finally, “Reduce Bureaucracy,” “Encourage Innovation,” and “Improve Culture” all reside at the internal process perspective. Although these three objectives obviously are quite ambitious, they still are attainable—or, at least, worthy of attention.

As appealing as the BSC approach may be, there might be situations in which it may not be as useful when compared with informal conceptual strategy mapping. For instance, it may be deemed too expensive for some organizations, too complicated, or just plain overwhelming. It also may conflict with idiosyncratic organizational barriers such as turf protection, competition for scarce resources, and resistance to broadscale change.

Weaknesses, in addition to the previous hindrances, include assumptions about rationality—shared by most behavioral/cognitive approaches—and the lack of integration opportunities within the internal processes perspective—for example, links between product development, operations management, and customer management. Along these lines, others argue convincingly for the adoption of value creation maps that incorporate interdependencies between tangible and intangible assets.

In spite of any shortcomings, BSC and strategy maps remain useful tools for strategic planning, systemwide change, and performance management enhancement. They just are not the major focus of this book. However, it is important to be aware of their existence. For instance, “Learning and Growth,” the lowest-level BSC perspective, is not represented in Figure 1-1 because it is hypothetical and limited just to the topics in the article about Boeing. Other objectives also are not represented that should be in a comprehensive strategy.

Instead, the focus of this book is more on clusters of challenges that organizations perceive as salient at a specific point in time. Moreover, most of the focus is on the internal processes perspective; that is, framing that is need-driven at a particular time—and not necessarily framed in the context of more encompassing variables. Finally, this book’s primary goal is to describe how to state (or frame) individual challenges and then link them together as frameworks to guide segments of innovation initiatives. Thus, the emphasis on strategy maps provides the strategic terrain needed to frame challenges productively.

FRAMING INNOVATION CHALLENGES

Even if you are not concerned with strategic innovation, the need still exists to frame challenges for productive idea generation. Innovation challenges at any organizational level should be relatively open-ended and target an explicit objective such as increasing product sales. However, there must be an appropriate, targeted focus. I once was asked to facilitate a brainstorming session faced with the following challenge: “How can we generate ideas for new floor-cleaning products?” Well, one answer is to use many idea generation techniques! Obviously, that is not the challenge. The umbrella objective may be to produce a lot of floor-cleaning products, but the means for doing this should be targeted at specific, subordinate challenges.

To illustrate, consider the floor-cleaning products example further. A common way to state challenges is to begin with the phrase, “How might we . . . ?” This provides a prompt for open-ended idea generation. It then is necessary to deconstruct the challenge into its parts, simply by asking basic questions representing potential subordinate objectives, such as the following:

•“What is involved in cleaning floors?”

•“What do people dislike about it?”

•“How often should floors be cleaned?”

•“In what ways are current floor-care products ineffective?”

The answers to these and similar questions then can be used as triggers for specific challenge questions. For instance, answers to the previous questions might lead to challenges such as:

1.“How might we make it easier to dispense floor-cleaning products?”

2.“How might we reduce the amount of effort involved in scrubbing a floor?”

3.“How might we make floor cleaning more convenient?”

4.“How might we reduce the frequency with which floors need to be cleaned?”

5.“How might we increase the sanitizing effect of floor cleaning?”

The outcome is a list of potential challenges that might be organized according to their priority and the order in which they should be dealt. In this instance, reducing the frequency with which floors need to be cleaned would help make cleaning floors more convenient. Thus, the first challenge to address might be the former. Because other factors are involved in making floor cleaning convenient, other secondary challenges also might be considered—for example, making it easier to dispense cleaning products. Based just on these limited examples, challenges #1 and #4 both might make cleaning more convenient. Although these examples certainly are not strategic issues, the basic principle of ordering challenges according to whether they are primary or secondary is the same, regardless.

NOTES

1.Simpson’s Contemporary Quotations, compiled by James B. Simpson (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1988).

2.Christopher M. Barlow, “Deliberate Insight in Team Creativity,” Journal of Creative Behavior, 34 (2): 113.

3.Robert M. Entman, “Framing: Toward a Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm,” Journal of Communication, 41: 55.

4.J. Edward Russo, and Paul J. H. Schoemaker, Winning Decisions: Getting It Right the First Time (New York: Currency/Doubleday, 2002), p. 22.

5.“Strategy Blockers,” Training & Development Magazine, August 2005.

6.Mark Turrell, “How to Connect Corporate Objectives and Investment in Innovation,” Innovation Tools, 2005. Retrieved November 25, 2005, from http://www.innovationtools.com/Articles/EnterpriseDetails.asp?a=202.

7.Thomas Mucha, “How to Ask the Right Questions,” interview with Peter Drucker, Business 2.0, December 10, 2004.

8.Ludwig Wittgenstein, Notebooks 1914–1916, entry for November 1, 1914. The Columbia World of Quotations (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996).

9.“I Like a Challenge—And I’ve Got One,” by W. James MacNerney, Jr., president and CEO of Boeing. In “News Analysis & Commentary,” Business Week, July 18, 2005.