CHAPTER 2

Creating a Sense of Excitement

IN 1999, Lion Brothers faced a serious challenge. Like many other firms, this leading manufacturer of apparel brand identification and decoration products had to find a way to correct the “Y2K” computer glitch that threatened to disrupt its information system with the coming of the New Year. As the company’s leaders searched for a solution, they realized that far more could be done than applying the straightforward software upgrade that was originally envisioned. Bit by bit, they grew in their understanding of lean business practices—and realized that it was time to rethink their very way of doing business.

For much of its one hundred–year history, this family-owned business, headquartered in Baltimore, Maryland, had operated using a “piece-part” approach. Jobs were broken down by the various steps that went into turning out completed products—from cutting out the blanks, embroidering patterns, and stitching components together, to trimming and finishing. Supervisors issued tickets to track the number of units workers completed; the more they completed, the greater their compensation. The real challenge came from managing all of this, involving a primarily manual process of balancing units with steps completed at various stages of processing and tracking the compensation for those who had performed these steps—an administrative burden that no commercial software could readily accommodate.

Implementing a Y2K solution meant the company would have to fundamentally restructure to reduce its administrative complexity. This, however, would create a range of challenges, each of which was far from trivial. For one, management had to convince its unionized workforce that this change was not only important to the company but that it was in their own best interest.

The company’s CEO, Susan Ganz, used this necessary change as the catalyst to set forth on an entirely different course. By creating outlets for its innovative capabilities, Lion Brothers could reach out in new directions, developing opportunities for growth in an industry in which others increasingly struggle to compete. But succeeding would require looking at the business in a very different way—transforming the way it operated, finding a means to better engage the customer, and building the flexibility to respond to continually shifting needs.1

Above all, it would mean gaining the understanding, participation, and even the excitement of not only its leaders but individuals across the workforce.

Setting a New Course

For Lion Brothers, identifying the challenge was fairly straightforward—the industry was rapidly moving overseas and losing business to low-cost producers—so it wasn’t hard to see that things had to change. But which way should the company go? And how could it create the needed excitement to carry the company forward even when hard decisions had to be made—engaging the workforce and keeping it moving in this new direction over time?

The first step was to gain consensus among key stakeholders on which direction to turn. Those leading the effort needed to become fully convinced before beginning a journey they knew could shake up their operations. Managers needed to clarify for themselves how the end result would look; they had to build their own vision, plan for action, and case for change.

At the same time, people across the organization needed to develop a deep trust in this new direction. This was critical for reaching an agreement to shift from the popular piece-part mentality and to recognizing how individuals would personally benefit. Its lean efforts would need to engage people of all backgrounds and at nearly every level in a structured way, building an understanding that went deeper than slogans or management directives.

Bit by bit its leaders internalized the conviction that this was the right move, created the plan to achieve the shift, and began a dialogue that made it possible to convincingly guide their staffs as they encountered the challenges that came from the significant changes they would put in place.

Developing a New Philosophy

Going Lean describes the most basic step in moving forward as developing a dynamic vision. Too often companies and institutions lay out a path for improvement that represents little more than a continuation of what worked in the past—even when it should be clear that the business environment that once made success possible has fundamentally shifted.

Perhaps this is why developing a truly lean vision often requires outside help—if nothing else, consultants can more easily see past the current mindset that is so hard to break and make a cold, objective assessment about what makes sense and what must be changed. This requires some analytics—data-driven assessment that goes beyond the intuitive. Most of all, it requires a fundamental rethinking of what the business really seeks to accomplish and what will be necessary to achieve the new goals, based on a strong understanding of the different possibilities that result from going lean.

Lion Brothers stood out in that it recognized the need to rethink everything; its industry’s fundamental shift had made it necessary to take a different approach altogether. Cost cutting alone could not be the answer; the company’s Chinese factory already helped it meet the low-cost challenge and enabled it to compete in markets driven predominately by price. Yet it understood that continuing to thrive in the future would require much more. To better engage its customers, it needed to transform how it did business to create a more specific understanding of their needs. It needed to create methodologies that made it possible to quickly and flexibly deliver innovative products. And it needed the ability to anticipate and provide for a broadening range of marketplace needs.

Meeting this challenge would demand a high degree of collaboration, new innovations to address emerging challenges and needs, and the means for quickly responding using flexible, cutting-edge operational capabilities. What it sought was to offer greater innovation, variety, and customized solutions than customers could get elsewhere. And so far the results seem impressive: Lion Brothers indicated that it continued to turn out significant profits in the face of growing overseas competition—even at the height of the 2008–2009 recession.

This focus—creating the means for better understanding the customers’ increasingly complex and dynamic needs, coupled with dramatically more responsive internal capabilities that promote constant innovation and dynamic strategies—is what lean dynamics is all about. It means shifting from the presumption that all will remain stable to a way of thinking that more accurately projects that the environment and the customer will continually change.

Lion Brothers and others point to the importance of developing a clear view of what one’s business will look like as the journey progresses. Executives, managers, and workers must understand the range of capabilities their company must possess to effectively respond to the dynamic challenges of its environment (which includes low costs—but goes much further). Leadership must learn to embrace a different ways of working, thinking, communicating, and innovating that together promote the creation of greater, cost-effective value—value that may not have been imagined before the transformation began (as described in Chapter 9).

Still, the most visible benefit of such an approach is that it forms a structure that progressively removes the greatest causes for waste to accumulate—thus creating rapid savings while preventing its recurrence as conditions continue to shift throughout its transformation. This is critical to sustaining trust that the shift is progressing as intended. But getting to this stage takes gaining the workforce’s support in the first place; everyone across the business must come to embrace the philosophy and its underlying principles, which will point workers in the right direction.

Involving the Workforce

Organizations embarking on business improvement initiatives today seem to understand the importance of engaging the workforce—making their people central to the solution. However, many companies appear to do a poor job of making this work. A fundamental disconnect comes from how they introduce their way of doing business to the workforce—a problem that is often exacerbated by their implementation approach.

Many organizations begin their improvement initiatives by immediately organizing teams of workers to seek out and implement changes. This can create tremendous problems. As described in Going Lean, the division of labor that governs traditional management methods compartmentalizes work, decision making, and information in a way that limits individuals’ “span of insight”—their ability to see the consequences of their actions. Immersing individuals in transformation activities before addressing this gap creates substantial problems—sometimes permanently alienating the workforce from the program and thwarting the possibilities for real improvement.

One common approach is to limit the scope of what they are asked to change—thus minimizing any disruption they might create. After completing some lean training, some workers are assigned to kaizen teams to identify improvements to an administrative function or some other activity peripheral to the business of the organization, whose disruption will not interfere with the broader activities of the business. Others might focus on actions aimed at increasing standardization or improving orderliness—applying “5S” methods as their primary emphasis as they seek to become lean.2 Workers dive in and accomplish what they are asked—later recognizing that all of their efforts really did not make the meaningful difference to the business’s competitiveness they hoped to achieve.

An alternate approach embraces the need to apply lean solutions to activities that strike at the core of a company’s business. Teams are trained and charged with making real, substantial change. Despite their enthusiasm, their limited span of insight (a natural result of their functional divisions) can impact their focus; they can miss substantial implications that affect the vastly complex business, which they cannot be expected to fully understand. When briefed to top leaders who do have the span of insight, these gaps will likely be recognized—potentially causing staff recommendations to be abandoned.

This highlights a key dichotomy facing lean transformations: The workforce needs to be involved, yet the workforce’s limited understanding restricts its central role in contributing to the solution. Proceeding without first addressing this natural disconnect can cause even well-intentioned actions to backfire, alienating workforces and undermining progress.

A critical first step is therefore creating a deliberate, structured approach for breaking down these barriers—beginning with making a sound, compelling case to spark everyone’s interest and building a deep understanding of why this shift is in their own best interest. As discussed later in this chapter, this case for change must clearly describe to everyone—from top leadership to the entire workforce—where the business is going and why it is headed there. All must come to see that no other alternative exists; the only choices are to change or to perish—a perspective that their current way of doing business likely prevents many from seeing.

Making the Transformation Personal

The quality of a workforce’s day-to-day actions must come from more than the company’s lofty vision or even its specific objectives; those can point the way ahead but cannot by themselves inspire people to achieve excellence. How individuals will act is largely driven by the personal factors that they face—whether their jobs cause them to see the value they create and to interact with others around them.

Managers and workers must be given a specific focus and rationale that goes beyond the conceptual and makes the change specific and personal. This is consistent with what I found in my own career. I learned that people work best when their motivation comes from within; when they are empowered to take ownership themselves. They accomplish more when they are made accountable to each other—not simply to their boss. Once they and their peers more clearly understand their goals and why they are important, they themselves can take ownership to drive up team performance. The result can be far beyond anything that management directives could possibly achieve—most of all, ownership causes people to become happier at work.

A lean dynamics approach, therefore, begins by implementing a different construct that promotes more personal involvement. Jobs must be structured so that people can better understand how various job efforts support each other and realize the impact their work has on the customer, as well as on the company’s bottom line. Workers should be measured for their accomplishments in promoting success against pertinent objectives instead of tracking efforts with unclear impact. Delegating decision making can increase agility and innovation; realigning information can promote simplicity while increasing the span of insight so necessary for eliminating lag.

Managers and workers must be given clear reasons why they are being asked to turn their world upside down and move in a direction that may not yet make sense—a graphic description of what is currently wrong and what direction the organization must take to correct it. Together all must come to see the crisis that surrounds them; they must understand how it is undermining their business or institution and threatening their combined interests. Moreover, they must come to understand that the solution is real—and attainable. Only then will they become capable of adapting to and adopting this construct for creating real, lasting value—and in doing so become more adept at protecting their real interests.

A great way to gain the necessary depth of insight might be through an offsite meeting to review the company or institution’s stated vision, strategies, objectives, and metrics, both at the top level and within those parts of the organization where improvements have been most directly targeted. This can point to challenges and stimulate understanding of methods to address the growing reality of uncertainty and change.

Establishing a Dynamic Vision for the Future

The starting point of any lean journey must be to identify what “value” means within the specific context of the company’s or institution’s mission and to assess how well the organization is suited to deliver that value. A lean dynamics approach further recognizes that a fundamental tenet of creating value is directly responding to the customers’ dynamic needs—giving them exactly what they want while sustaining the highest quality, lowest price, and greatest innovation, even when facing rapidly changing, unexpected circumstances.

How should an organization begin? By assessing its current state—determining how well the business as a whole is able to create value, not only for the conditions it anticipates but across the full range of dynamic circumstances it must face. A key focus should be its ability to create corporate value (e.g., profit, growth, or greater competitiveness) across dynamic conditions—something that is often not well understood.

Sustaining strong internal capabilities is a critical measure of a company’s ability to create strong customer value, even in a crisis. Why is this? Think about a passenger jet’s procedures in case of an emergency landing: Rather than placing the oxygen mask on your child, you are asked to first attend to yourself. The reason is simple: You must remain strong and capable in order to support those who depend on you. In much the same way, a company that prepares itself to avoid internal disruptions will be able to seamlessly continue to support its customers—preventing workarounds and waste that can undermine quality, consistency, and innovation.

A dynamic value assessment focuses on the business’s value in response to dynamic conditions as a powerful means for understanding how well it is positioned to continue to serve its customers. It evaluates what the firm or institution produces today, how well it accomplishes this, and how well this meets its customers’ needs. This includes an assessment of the dynamic conditions outside of the business—shifts in customer needs and desires, business conditions, and emerging opportunities and threats within its operating environment. From this, a rigorous evaluation of how well the organization will perform when it faces these conditions is conducted. (See Appendix A for a dynamic value assessment framework.)

This dynamic look at the business drives a different starting point from many of today’s lean initiatives. Rather than correcting waste as it is found, it starts by looking across the business, from the company’s suppliers to its customers. And instead of focusing where problems become most evident—at the end of the line such as a manufacturer’s assembly operations—it seeks to identify the greatest sources of lag anywhere across its continuum of value creation that causes this waste to accumulate in the first place.

Starting with this dynamic value assessment is critical because it builds a baseline understanding of how well the company is structured to sustain value over time, progressively advancing the company’s ability to create value in a way that makes it less likely to stumble despite the challenging circumstances it might face along the way.

Mapping the Value Curve

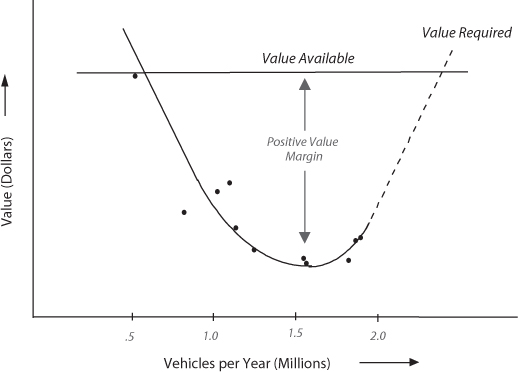

How is dynamic value measured? By using the value curve—a graphic representation of the organization’s ability to generate bottom-line, tangible value as it responds to the broad range of dynamic conditions it must face. Figure 2-1 illustrates the value curve for a classic American corporation during a historic timeframe: General Motors between 1926 and 1936, a string of years that swung from prosperity to the Great Depression.

Figure 2-1. The Value Curve3

What does this figure show us? It compares the company’s value as perceived by its customers, assessed in tangible terms by what they are willing to pay for what the company produces (the top line in the figure representing the value available to the company) with the portion of this value necessary to produce these products (its value required). These are graphically compared to illustrate what is most important: their relationship across the company’s range of business conditions (Appendix B describes the construction of the value curve).

We can see from its value curve that this example of a classic American corporation was not built for the dramatic shift in operating conditions it was forced to deal with. Like most traditionally managed corporations, it was designed to function efficiently within a narrower, specific rate of anticipated demand. The company’s value margin—the portion of value that remains available to the corporation to maneuver—dropped off quickly as conditions significantly changed, a phenomenon marked by its steep, U-shaped curve.

Many companies today are governed by even steeper U-shaped value curves—a surprising development given decades of cost-improvement initiatives (it is how they apply such initiatives that seems to contribute to this result). Lean businesses, however, display a distinctly different focus, resulting in a dramatically different value curve pattern. Rather than optimizing for a narrow range of conditions, these firms perform consistently even when market conditions substantially change. As a result, they take in more value and expend less to do so, as is evident from the stark difference in their value curves.

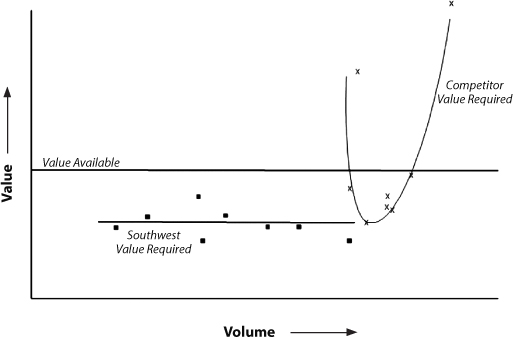

Figure 2-2 illustrates the value curve for one such corporation, Southwest Airlines (depicted on the left of the chart), and compares its performance with one of its peers during the particularly challenging timeframe including the aftermath of September 11, 2001. Southwest’s value curve looks virtually flat, a stark contrast to its competitor’s steep, U-shaped curve. What does this tell us? The company continued creating steady value during the most difficult period this industry faced, while its peers struggled or fell into bankruptcy. It continued to offer sustained value as others grounded airplanes, abandoned gates, and furloughed employees. And it subsequently found opportunities to advance, expanding routes and picking up gates abandoned by competitors.

Figure 2-2. Southwest Versus the Airline Industry4

The value curve assessment offers a specific, objective means for raising awareness of the need to change directions. Its findings can point to a much more powerful program for improvement, not just for trimming costs, but for promoting dynamic strategies and responsive capabilities that are critical for sustaining bottom-line value. Moreover, they can serve as a valuable tool for gaining the buy-in across the work-force that is so critical yet so often absent.

By helping individuals understand the importance of change to the future of the corporation and building metrics that support the increments of change that they can better see are needed, people across the business can better understand why and how they must participate.

Key Point: How Do I Map a Value Curve?

An analyst sought to create a value curve for a business. After a couple of false starts, he quickly became proficient when he realized the process involved only five basic steps (additional details are provided in Appendix B).

1. Measure the company’s creation of value. The analyst knew that the first step was to determine the company’s value available—in tangible terms, what dollars were available for conducting all aspects of business. Upon reflection, he realized that this is the same as what customers perceive to be the value of the company’s product: how much they are willing to pay for what the company offers, accounting for the other choices available and their changing needs, desires, and constraints over time (derived from the business’s net sales).

2. Relate this to what it takes to create this value. He recognized that the company’s value required—what it costs to create this value—is far from constant; it varies depending on the conditions that exist at the time. Rather than adding up the individual costs of all of its activities, expenditures, and wastes, he calculated this using a simpler, equivalent method: based on determining the difference between net sales and net income—a top-down way to determine costs within those conditions.

3. Track the organization’s response to changing demands. Until this point, he could see nothing particular revealing; he needed to plot these results against a measure that would show how these related to each other across the company’s entire range of operating conditions. This meant comparing the value available and value required for the number of products sold per year. (Note: this varies by business type, as described in Appendix B.)

4. Plot the data. To make the relationship between value available and value required more visible, he represented value available as a constant and calculated and displayed its proportionally adjusted value required (Appendix B). He plotted the proportionally adjusted value available and value required points against the rate of demand each year over a ten-year timeframe.

5. Evaluate the results. The analyst found that the “curve” was optimal for only a narrow range of conditions, indicating that this company’s lean efforts had not yet attained a result consistent with that seen for those at the highest level of lean dynamics, so he decided to investigate further (described in Appendix B).

Assessing the Challenges

By now the underlying focus in shifting to lean dynamics should be clear: to flatten the value curve—shifting from a steep V-shape to a less steep U-shape and ultimately to remain flat across a wide range of circumstances. Still, the value curve represents only a bottom-line indication of firms’ maturity in attaining this goal. Advancing requires establishing and implementing a dynamic vision of the future consistent with those benchmarks that have pointed the way by attaining a flat value curve. The value curve breaks down our understanding of what they do into three basic components.

1. Creating and sustaining strong and sustainable customer value, translating to consistent value available to the corporation (the top line of the value curve) even in times of sudden demand shifts and changing needs

2. Building flexible, innovative, low-cost internal capabilities—or steady value required (flattening the U-shaped curve)—which are instrumental to supporting new opportunities that arise during challenging conditions

3. Establishing dynamic business strategies that flexibly respond to challenging conditions and promote a strong, steady value margin for continued value creation and advancement

Building a clear and compelling vision is critical. Doing so means formatting the specific challenges highlighted by the dynamic value assessment in a way that is easily understood by everyone across the business: corporate executives, stakeholders, suppliers, and individuals across the workforce (and perhaps even key customers). Using clear examples—presenting familiar problems and challenges within a context of today’s dynamic challenges that will likely be brand new—this case must clearly show that there is no other choice but to make a change to lean dynamics.

In some cases, the threats might be particularly serious; companies might find themselves in a situation where the worst of the environmental dynamics described earlier have already struck. Firms’ natural inclination is to react, as was described in the previous chapter. Clearly the first step is to regain stability; interim buffers, workarounds, or other wastes might be needed. By applying these as deliberate actions with the end goal in mind, they can help minimize any additional lag, while promoting the rigor, discipline, and span of insight needed to advance once operations stabilize.

Moreover, it is not enough to simply identify that the business or institution must change; determining its path to improvement is equally critical. Those leading the way must progressively mitigate the dynamic effects on their business and their customers, while pursuing different approaches to creating new forms of value, a key to thriving in today’s competitive marketplace. It is therefore critical to identify a way that will lead to a fundamental shift in the value curve—something that will take time to achieve but, as this book will show, will create interim benefits that will help improve value and sustain the course as it progresses.

Key Point: Interpreting the Value Curve

The shape of the value curve offers powerful insights into an organization’s underlying “leanness”—showing whether it is structured to meet the challenges it will increasingly face within today’s increasingly dynamic environment. A steep, narrow, U-shaped value curve indicates that its way of doing business is optimized for stability and predictability, indicating that:

![]() Inflexibility is inherent. Companies that structure operations, decision making, information, and innovation to progress efficiently and effectively within only a narrow range of anticipated conditions are ill-suited to the challenges that occur when uncertain or changing conditions emerge. The result: Loss skyrockets when conditions inevitably shift.

Inflexibility is inherent. Companies that structure operations, decision making, information, and innovation to progress efficiently and effectively within only a narrow range of anticipated conditions are ill-suited to the challenges that occur when uncertain or changing conditions emerge. The result: Loss skyrockets when conditions inevitably shift.

![]() Waste is built in as a fundamental way of doing business. Traditional methods based on maximizing economies of scale inherently build in lag, which amplifies internal variation and disruption when subjected to change. Since waste is a natural response to this lag, the solution must be to address lag—not its outcomes—in order to mitigate this spiral of loss.

Waste is built in as a fundamental way of doing business. Traditional methods based on maximizing economies of scale inherently build in lag, which amplifies internal variation and disruption when subjected to change. Since waste is a natural response to this lag, the solution must be to address lag—not its outcomes—in order to mitigate this spiral of loss.

![]() The solution must go beyond narrow targets. Going Lean showed that firms can apply business improvement methods to save hundreds of millions of dollars without making a meaningful impact on the shape of their value curve. While cost cutting might be part of the answer, higher efficiencies across a broad range of conditions—the real need today—come from a fundamental restructuring rather than from simply attacking “waste.”

The solution must go beyond narrow targets. Going Lean showed that firms can apply business improvement methods to save hundreds of millions of dollars without making a meaningful impact on the shape of their value curve. While cost cutting might be part of the answer, higher efficiencies across a broad range of conditions—the real need today—come from a fundamental restructuring rather than from simply attacking “waste.”

![]() Lean initiatives should not be peripheral to the central value-creation focus of the business. What good does “leaning” a process do if its transformation has no impact on the value curve? The value curve’s bottom-line measurement can help guide improvement activities toward staying on target, focusing them on what is really important to the company and its customers.

Lean initiatives should not be peripheral to the central value-creation focus of the business. What good does “leaning” a process do if its transformation has no impact on the value curve? The value curve’s bottom-line measurement can help guide improvement activities toward staying on target, focusing them on what is really important to the company and its customers.

![]() Customer needs must be well understood. A steep value curve offers solid evidence that the company or institution does not fully understand its customers’ dynamic needs. Perhaps it addresses them in aggregate, as if they all behave the same, or focuses on only limited portions of their needs. This can translate to poor responsiveness to real conditions, undermining customer trust and loyalty.

Customer needs must be well understood. A steep value curve offers solid evidence that the company or institution does not fully understand its customers’ dynamic needs. Perhaps it addresses them in aggregate, as if they all behave the same, or focuses on only limited portions of their needs. This can translate to poor responsiveness to real conditions, undermining customer trust and loyalty.

![]() A lean shift will take time. Although implementing lean dynamics can produce rapid, dramatic benefits, shifting from a steep U-shape to the advanced state marked by a flat value curve will not occur overnight. Still, the value curve can serve as a reliable beacon on the horizon, guiding the way. In conjunction with intermediate measurements it can show progress along a pathway that may otherwise create confusion.

A lean shift will take time. Although implementing lean dynamics can produce rapid, dramatic benefits, shifting from a steep U-shape to the advanced state marked by a flat value curve will not occur overnight. Still, the value curve can serve as a reliable beacon on the horizon, guiding the way. In conjunction with intermediate measurements it can show progress along a pathway that may otherwise create confusion.