CHAPTER 3

The Road to Lean Advancement

GOING LEAN BEGAN with a simple observation: “Excellence is best seen in a crisis.” The way in which a business responds when confronted with a major challenge points to its deeper capabilities, not only for avoiding the dramatic breakdowns so widely seen today, but for reaching forward to embrace fresh opportunities and set new value standards as business conditions continue to evolve.

The value curve is particularly powerful because it clearly depicts this phenomenon by graphically illustrating firms’ bottom-line capabilities for sustaining steady value across the breadth of conditions they might face. Those demonstrating greater preparedness and adaptability within today’s dynamic conditions often advance to lead their industries in key measures of performance (demonstrated in Going Lean), reinforcing the value curve as the new yardstick for measuring a business’s progress.

Yet attaining value curve excellence is a significant and challenging undertaking. Companies do not transform themselves to a flat curve in a single leap; rather, the evidence points to a need for a carefully structured program that progressively mitigates major sources of lag and loss over a number of years on the journey toward this state of sustainable excellence. Staying on course, therefore, requires tracking one’s progress against a beacon on the horizon (such as the promise of attaining a flat value curve).

Complicating matters is the reality that such projects rarely begin from scratch—most are affected by either progress or false starts from previous efforts. Some organizations might have realized initial successes with lean tools or practices; still others might have stumbled, leading personnel across the business to simply increase their resistance to change. Either way, firms must begin by reassessing where they stand and where they are going, maximizing what lessons they have learned and capabilities that already exist, and setting a course for overcoming the hurdles that stand in their way.

Beginning the Journey

Like many aerospace producers, Cessna Aircraft Company began experimenting years ago with techniques to improve the efficiency of its operations. It began by applying lean and Six Sigma tools as tactical fixes—“planting seeds” for improvement across a wide range of activities, from operations to finance and legal support, whose bottom-line benefits were only generally understood.1

This methodology is not much different from what is commonly applied within companies and institutions of all types today. Many seem to focus on eliminating wastes, identifying areas where extra inventories, padded schedules, and extra processing steps are clearly evident and then “leaning” them out. Often this begins with work standardization or other efforts aimed at tightening existing business activities to make businesses operate more smoothly while minimizing operational costs—quickly and visibly generating savings before declaring victory and moving on to another project.

What makes Cessna’s efforts stand out is the deeper understanding that seems to have sprouted from widespread experimentation. It increasingly shifted focus from fostering localized wins to attaining deeper transformation. While the company continues to encounter significant bumps in the road, its fundamental shifts in philosophy, changes in organizational structure, and more substantial implementation methods seem to have kept it on course, improving the dynamic stability of its operations while progressively transforming the business as a whole.2 The way in which it moved beyond its initial stages and its determination to press forward through difficult times offer important insights into the road to lean maturity.

Seeing Beyond Traditional Solutions

As is often the case, Cessna’s greatest advancement grew out of crisis. It stemmed from a need to overcome a major challenge when demand for its airplanes suddenly spiked to several times beyond normal levels. The result was immediate and dramatic; what worked well when production was at 75 jets per year no longer sufficed when production quickly grew to between 300 and 400 planes. Parts shortages skyrocketed; schedule interruptions broadly impacted the progression of work.

The company quickly recognized that slashing waste was not in itself the answer; waste reduction would do little to overcome the dynamic challenges it faced. What it really needed was a means for improving predictability within its operations despite extreme change and unpredictability, preventing loss from skyrocketing while increasing its available capacity.

Our focus shifted to things like ramping up production to accommodate 10 more jets, or to slashing service time to keep our customers’ aircraft in the air—not cost, which became more of a strong secondary consideration. We began asking ourselves why we are doing this, instead of how.

Tim Williams, Cessna’s VP for Lean Six Sigma3

Cessna’s challenge was not unique; it illustrated a condition that has long plagued the business of aerospace: companies’ struggle against operational turmoil arising from sudden spikes and downturns in customer needs, translating to difficulty in signaling and coordinating activities across its vast, complex string of activities. Parts shortages are not uncommon; production delays, “traveled work” (completing work steps at subsequent stations to keep from holding up later steps), and other workarounds are normal steps that seem widely accepted as the way things work. Consider the challenge described decades ago:

The problem of scheduling aircraft fabrication is what one might call “complicated simplicity.” It is not all academic or a series of numbers that can be multiplied and divided to get the answer. Much of the success of any scheduling system is due to the use of plain “horse sense” by the scheduling personnel.

Production manager for Beech Aircraft, 19434

Like many firms across this industry, Cessna had become accustomed to the internal turmoil that comes from such shifts. However, the understanding it had gained from its lean “Black Belt” efforts seemed to spark a deeper recognition that real change was possible. The company’s focus began to shift. Less and less attention was given to the dollar savings of these efforts; attention shifted to understanding the real, bottom-line impact of these activities on overcoming its deeper issues. What was once a series of niche projects became increasingly understood for their deeper importance, with their contributions increasingly linked to and reported against the corporation’s strategic plan and objectives.

Finding the Road to Lean Maturity

Cessna knew that it needed greater flexibility to respond to suddenly shifting demands and cancelled orders, continual production and configuration shifts, and changing delivery sequences and shifting customer requirements. This shift in thinking toward identifying clear focal points for its transformation (a concept described in Chapter 6) fostered a fundamental change from applying lean and Six Sigma tools for moving in a general direction toward concentrating on meaningful but manageable elements and addressing them through a structured progression of activities.

It became clear that chasing the problems where they became most evident was not the answer; the root cause for disruptions in assembly could often be traced far upstream, often to problems within its supplier base. Part of the problem was the complexity of Cessna’s sourcing approach, which depended on a vast supplier base whose layout was far from intuitive. Multiple suppliers provided the same types of parts, fragmenting demand and amplifying uncertainty. Moreover, the company’s work with its suppliers had revealed a number of challenges the company was creating itself.

This realization sparked a focus on fundamentally transforming how the company structured and managed its supplier base. One element was its Center of Excellence (COE) program, a series of efforts focused on optimizing its supply base by narrowing it down to include only “very select suppliers based on their dedicated support to product families” (an important concept further described in Chapter 4).5 The company leverages its cross-functional commodity team to scrutinize the details of thousands of parts and components, identifying commonalities in materials, processing characteristics, or other features that point to synergies that would enhance suppliers’ ability to become more efficient and quickly respond to changing needs. By choosing suppliers based on their ability to create efficiencies by producing parts for specific product families and procuring items based on their alignment to these families, the team has slashed its costs and dramatically reduced lead times.

The company’s supplier efforts over the last decade have led to powerful results: Suppliers’ on-time deliveries improved from 42 percent up to 99 percent, and their quality defects dropped from a high of over 11,000 per million to 550 as of the end of 2008, while achieving substantial cost reductions. But the impact on the core focus for change—reducing disruption due to problems with material availability—is particularly impressive. Stock-outs for the 74,000 part numbers delivered plummeted from over 1,000 per week at its peak to an average of only 6 per week in 2008.6

Cessna’s increasing lean maturity is evident in its evolving organizational structure. The company previously aligned its substantial pool of Black Belts—set at 1 percent of its total workforce—under a central office, shared with operational units as needed to provide insight and support to their efforts. Their accomplishments were measured in the same piecemeal way, estimating savings from individual lean projects. At the end of 2008, this all changed. The company now places its Black Belts directly into the organizational elements they support—a structure that normally would have brought tremendous risk that individuals would simply be redirected to performing day-today work. But so far, this has not been the case; improvement efforts do not seem to be dropping off. With this, Cessna had made a leap in lean maturity—it progressed from implementing lean as a series of discrete, separately managed projects to an accepted, central part of managing the business.7

These results are particularly powerful in that they demonstrate that lean methods can extend beyond the simpler environments that most often serve as examples; it shows that powerful gains are possible within one of the most complex business environments—offering potential that extends well beyond aerospace. Hospitals, for instance, might face uncertain demand, treating patients who have widely ranging backgrounds and needs—yet managed using a system designed for sameness and stability. Educators face an enormous challenge; they operate within a structure built for tremendous stability, while they increasingly face the need to constantly and quickly respond to market changes and the individualized needs of their customers—a dramatic shift from the stable, standardized course offerings and delivery methods under which these institutions thrived in the past.8

Each of these faces a common challenge: They need to overcome the temptation to follow the path that so many others are taking and instead transform to better operate within an environment that is very different from what they faced in the past. Most importantly, they must recognize that this transformation does not come in a single step; improvement occurs incrementally. It takes progressive growth in understanding, capabilities, and breadth of application over time to advance lean maturity in a steady and structured way.

The Five Levels of Lean Maturity

Too often I hear lean practitioners declare that going lean can be boiled down to a single term: “continuous improvement.” Unfortunately, this sets the bar very low—it offers a great excuse for approaching lean in any way or fashion a manager might choose. Within that context, almost any gains at all can be considered a success. After all, can anything be considered a failure if lessons are learned from mistakes along the way?

Continuous improvement (or kaizen, in lean terminology) is clearly a central part of any program for going lean, just as are the many tools and practices that make up a lean methodology. Yet managers should not simply apply lean tools in an intuitive manner. Applying lean tools and practices without first establishing a corporate-wide, end-to-end overarching structure might serve only to refine the status quo—reinforcing the way their company or institution already operates, within the plateau at which it already exists.

This is perhaps the greatest challenge for corporations and institutions: seeing past their current performance level and recognizing the means—and the need—to move to a different level altogether. This is particularly evident from looking at lean efforts today; firms and institutions seem to plateau at distinct levels of maturity. Why does this happen? Perhaps because firms and institutions become satisfied with continuous improvement within these plateaus. By applying tools and practices aimed at stretching what worked well a little further they make incremental improvements that yield quick victories rather than long-term advancements in corporate competitiveness and value.

The problem this creates for companies and institutions should be clear to readers by now; real success within today’s dynamic environment takes breaking out of their current mold to shift upward to an entirely new level of performance. But doing so requires seeing past the traditional view of continuous improvement, instead aiming their efforts toward advancing to higher levels of maturity. Finding the way to accomplish this means putting together the lessons from today’s vast experimentation—the principles, experiences, and skills proven over time to advance firms or institutions to the next level—and finding the means for navigating through the natural sticking points in the progression toward achieving sustainable value.

Recognizing the Plateaus

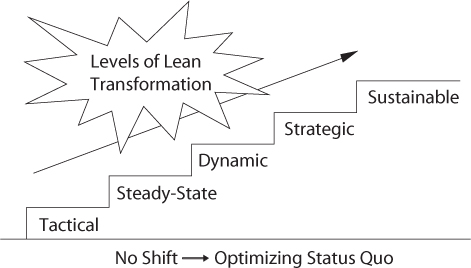

Companies generally appear to begin their journeys much as was done at Cessna: as a series of projects, tackling discrete issues in a tactical manner. But Cessna was able to advance beyond this; it saw the need to pursue higher levels of maturity. What are these levels? After observing and researching lean initiatives over time, I began to see a pattern. Despite focusing on “continuous improvement,” all lean efforts do not appear to continuously progress. Instead, they appear to fall into a series of plateaus—distinct levels of their advancement in maturity, as depicted in Figure 3-1.

Figure 3-1. Levels of Lean Maturity

The most basic level is no shift at all—simply accepting the status quo, tightening up existing processes using a wide range of measures aimed at better dealing with the challenges firms or institutions face today. Many seem intent on applying modern tools and techniques, ranging from information technology solutions to long-term supplier arrangements, as a means to overcome the disconnects that cause increased costs that impact their bottom lines. Yet, while these appear to succeed in cutting costs, they might also create increased inflexibility to change—amplifying the downward spiral of loss when later subjected to uncertainty and change.

A much more common starting point is implementing tactical lean—an array of initiatives driven by the general rhetoric of “cutting the fat.” Many companies and institutions today fall into this category; they tend to attribute virtually any savings to “lean”—presumably as a means for demonstrating their success to senior management. Without sufficient attention to deeper, more transformational activities, efforts can stagnate after an initial increment of improvement, causing a serious loss of support if workers and managers see it as a superficial fix rather than a means for addressing the more serious challenges that remain. In some cases this first step could be portrayed as a step down. It can create barriers to lean improvement that far exceed the first-level savings realized from pockets of waste reduction.

More advanced is steady-state lean—an end-to-end approach to addressing issues affecting the operational flow of a value stream. These efforts often begin in pursuit of whatever challenge presents itself first, with a primary emphasis on eliminating waste within current operating conditions. Some businesses progress farther, advancing to apply many of these principles to attain an increased focus on dynamic lean—leveraging lean tools and practices to create an ability to right themselves when things go wrong, maintaining internal stability and, therefore, more consistent delivery of value, despite uncertain or shifting conditions (these levels are discussed further in Chapter 7).

Companies like Toyota go farther still, advancing to strategic lean—pursuing new business strategies by drawing on their greater internal stability to create steady, growing value across a broad range of circumstances. Companies like Southwest Airlines appear to have advanced to the ultimate maturity level—attaining what might be described as sustainable lean. These businesses have succeeded in so deeply entrenching the principles of lean dynamics that their value curves—the hallmark of lean—remain virtually flat even in today’s crisis. They look beyond such traditional measures as market share and advancing at a strong but cautious pace. Perhaps more importantly, they succeed in driving a fundamental shift in how leaders view the creation of value for their customers—reaching out to transform the business environment and reshape customer expectations to better value their capabilities.

Their sustained excellence demonstrates what some have long surmised—that restructuring to a different way of doing business can overcome many of the challenges that have been traditionally simply accepted as part of doing business. These organizations ultimately transform the business environment itself—raising the bar for value across the industry and transforming expectations for customers and the workforce alike.

Creating a Structure for Advancement

What is particularly important about recognizing these levels of lean maturity is the visibility it can create for companies regarding the range and challenges of lean projects. By understanding the continuum of this journey, those leading the efforts can better understand where they stand now and where they must go from there.

Businesses that plateau at one of these levels can run into a number of critical challenges. For instance, they might lose the support of their workforce when personnel tire of stagnating well below the potential gains touted by those leading the efforts (as well as top managers who wish to shift to other initiatives that hold greater promise). Moreover, they might encounter environmental turmoil that undermines the progress of efforts that have not reached sufficient maturity to sustain results (described in Chapter 4). Either of these can cause initial gains to erode; perhaps more damaging is the risk of undermining the workforce’s belief in lean as a meaningful solution.

Thus, simply embarking on a program of unstructured continuous improvement is not enough. By instead working toward stabilizing their positions while striving toward the next levels of maturity, it stands to reason that they will increasingly reduce the potential that disruptive forces can lead to backsliding or abandoning their efforts altogether.

Key Point: Assessing Your Starting Point

An important first step is to identify where on the continuum of lean maturity one’s organization stands. This can help point to the general mindset that exists—a key foundation for creating the vision, case for change, and plan of action that can set the course to advancing to sustainable lean (the ultimate state of maturity represented by a flat value curve). This is a critical step; it is most important in the organization’s potential to continue to advance despite the pressures to stagnate and simply refine gains within a given level of maturity. Some questions that can help include:

![]() Does your company or institution focus many initiatives on attaining different targets, such as faster inventory turns or cost reductions? Are tool descriptions, such as 5S and value stream mapping, intertwined in these targets? If the answer is yes, it is probably firmly fixed on a tactical lean plateau.

Does your company or institution focus many initiatives on attaining different targets, such as faster inventory turns or cost reductions? Are tool descriptions, such as 5S and value stream mapping, intertwined in these targets? If the answer is yes, it is probably firmly fixed on a tactical lean plateau.

![]() Rather than accumulating discrete cases of waste reduction, do you instead seek to create a deeper capability for leveling flow from end to end across the enterprise? Have you identified clear objectives and metrics that readily tie to bottom-line results, driving workers and managers to emphasize this focus in their day-to-day duties? If so, your business might have reached the level of steady-state lean, realizing such broader benefits as freeing capacity to be applied toward other areas needing transformation.

Rather than accumulating discrete cases of waste reduction, do you instead seek to create a deeper capability for leveling flow from end to end across the enterprise? Have you identified clear objectives and metrics that readily tie to bottom-line results, driving workers and managers to emphasize this focus in their day-to-day duties? If so, your business might have reached the level of steady-state lean, realizing such broader benefits as freeing capacity to be applied toward other areas needing transformation.

![]() Would you consider your business improvement methods to be focused on enhancing processes or on value as defined by the customers, even if they keep changing their minds? This is a critical distinction that points to a focus on dynamic lean. Emphasizing process redesign can cause leaders to become fixated on how to achieve an existing target, instead of exploring what that target should be. Seeking instead to understand the dynamics of value and focus on optimizing its incremental buildup can redirect attention to opportunities for transformation at each step along the way.

Would you consider your business improvement methods to be focused on enhancing processes or on value as defined by the customers, even if they keep changing their minds? This is a critical distinction that points to a focus on dynamic lean. Emphasizing process redesign can cause leaders to become fixated on how to achieve an existing target, instead of exploring what that target should be. Seeking instead to understand the dynamics of value and focus on optimizing its incremental buildup can redirect attention to opportunities for transformation at each step along the way.

![]() Do maximizing innovation and seeking new opportunities factor heavily into your approach to lean? Are product families optimized with this in mind; are design personnel, top executives, and other parts of the organization showing great interest and involvement in your progress and contributing as team members for identifying and rolling out new phases in your progression? If this is the case, you may be approaching or at the level of strategic lean.

Do maximizing innovation and seeking new opportunities factor heavily into your approach to lean? Are product families optimized with this in mind; are design personnel, top executives, and other parts of the organization showing great interest and involvement in your progress and contributing as team members for identifying and rolling out new phases in your progression? If this is the case, you may be approaching or at the level of strategic lean.

![]() Does your organization break from the tradition of fixating on attaining market share, instead focusing on ways to sustainably advance in creating customer and corporate value? Is your value curve flat? You may have attained the elite rank of sustainable lean, a level that only a limited number of organizations have reached. If this is the case, you already know that your journey is far from complete; retaining this capability takes constant vigilance, innovation, and hard work, but doing so creates enormous satisfaction, not only for the customer but for individuals across the organization as well.

Does your organization break from the tradition of fixating on attaining market share, instead focusing on ways to sustainably advance in creating customer and corporate value? Is your value curve flat? You may have attained the elite rank of sustainable lean, a level that only a limited number of organizations have reached. If this is the case, you already know that your journey is far from complete; retaining this capability takes constant vigilance, innovation, and hard work, but doing so creates enormous satisfaction, not only for the customer but for individuals across the organization as well.