CHAPTER 7

Taking Action

MANY YEARS AGO I was shocked as a manager related his inclination to “err on the side of action,” despite facing significant unknowns. This contradicted all that I had been taught as an aerospace engineer. As my career progressed, I grew to see that this manager’s inclination to charge ahead in the face of unresolved challenges was far from unique—particularly within the realm of process improvement.

This propensity to leap to action might have something to do with how directly efforts will affect the bottom-line value. For instance, it seems rare within engineering design functions, where the impact is clear and direct. Problems with configuration or functionality will directly affect quality, cost, reliability, and customer satisfaction. Conversely, lean projects within large businesses and institutions can be introduced in a way that is so peripheral to the core of the business that interruptions pose little immediate risk. This means the consequences of making mistakes will be less severe. It also means that results can have far less meaning.

Perhaps this is why managers seem willing to launch into their lean efforts with little up-front analysis of the specific impact these might have on their business. Many seem to emphasize trial and error as the means for adapting lean principles to their own particular circumstances. Yet, this can create turmoil, which can lead to loss of workforce support (described in Chapter 5). Moreover, it likely contributes to the tremendous potential for firms and institutions to quickly plateau after attaining initial gains.

What is important, then, is creating an approach for advancement that permits flexibility for experimentation, but does so in a structured manner, focusing on the key aspects of implementing lean dynamics described throughout this book: following a consistent vision, creating attainable focal points, and advancing through organizational decentralization.

An Iterative Cycle to Advancement

Consider the advantages offered by an iterative approach to advancement, in which a cycle of assessment, focus, action, and measurement progressively increases a business’s lean capabilities. Guided by an overarching vision and objectives and structured with decision points for evaluating progress and prioritizing the next steps for optimizing progress, such an approach offers the needed flexibility while maintaining rigor and focus through each phase along the way.1

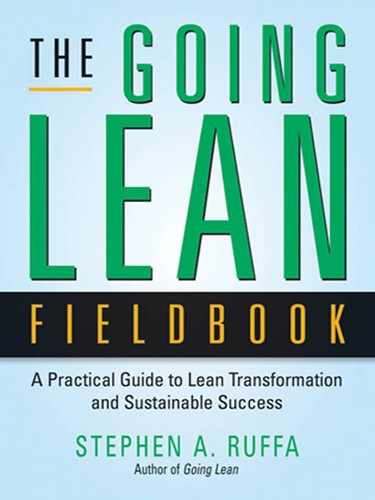

Figure 7-1 proposes such a structure for guiding the lean dynamics journey. The core of this transformation cycle is a dynamic value assessment—the critical step of sorting through a business’s or an institution’s operations, determining the best starting point for advancing their creation of value within real challenges of its business environment (described in Appendix A). It establishes the foundation for the activities that will follow; in particular, identifying transformation focal points—a key to focusing improvements in a deliberate direction based on the current capabilities and needs of the business (as described in Chapter 6). Transformation begins by establishing cross-functional teams with the span of insight for identifying and managing specific solutions to advance these focal points (promoting organizational flow, described in Chapter 5). Next comes implementing the shift. Finally, since actions should produce broad-based benefits, it is important to stabilize the restructured activities to validate the extent of results.

Figure 7-1. Lean Dynamics Transformation Cycle

The cycle continues with follow-on analyses intended to reveal the next tier of transformational focal points, which begins the cycle all over again. Each repetition of the cycle should help drive the company or institution farther along its journey to lean maturity.

A key advantage is that this structure can be applied at any level of progress and then reapplied once new progress is made, enabling businesses or institutions to advance beyond their current plateau, overcoming common vulnerabilities and addressing a broad array of critical challenges. It permits flexibility but avoids constant drift as improvements are incorporated across the business. And it introduces improvements in a tightly coordinated manner—just as is seen at lean benchmarks—synchronizing changes with ongoing operations in a way that mitigates any disruption that might introduce waste.

Conducting follow-on dynamic value analyses at each iteration (as depicted in Figure 7-1) is critical to sustaining the momentum and revealing that far more is left to be accomplished. Additional challenges, new focal points, and refined objectives and opportunities will likely become visible through increasingly specific measurements, greater baseline stability, and the progression of capabilities.

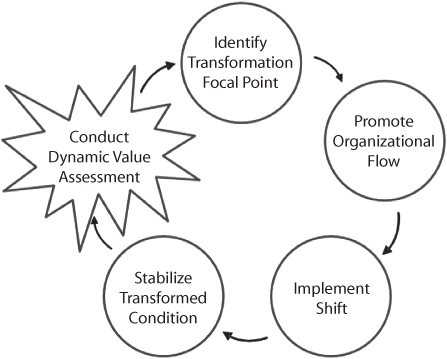

Each new assessment creates the need to decide on new paths and projects; this offers a chance to engage the steering committee (described in Chapter 6), whose involvement, ideas, and enthusiasm can reinforce the mindset that going lean must represent more than discrete, continual improvements. Each cycle can help drive the organization toward greater levels of lean maturity as it ultimately moves up the continuum introduced in Chapter 3 (depicted in Figure 7-2).

Recognition that advancement is marked by distinct levels of maturity, marking common levels of understanding, capability, and progress, is critical to this cycle to advancement. Not only does this understanding serve to highlight the stages of the journey ahead, but it helps reveal the limiting mindset that drives so many to become complacent and fail to progress after reaching these distinct plateaus along the way. Moreover, it is important to recognize that only when organizations reach the upper levels of maturity do they seem to attain a distinct change in their value curves. This points to a real need for overcoming the challenges to reaching this critical destination in the lean journey.

Figure 7-2. Levels of Lean Maturity

Advancing Up the Levels of Lean Maturity

How, then, can this cycle to improvement help to overcome the plateaus in advancing in lean maturity? The unfortunate reality is that many companies and institutions do not progress beyond the first steps to a dynamic lean approach, and fewer still pursue a course of strategic lean (as evidenced by the limited examples of flat value curves that mark this level of maturity). Without a structured approach to advancement, it is easy to stagnate, focusing on perfecting their capabilities at each plateau along the way rather than on implementing transformative efforts that stretch toward more advanced levels of maturity.

As shown at the base of Figure 7-2, many organizations plateau without making any lean shifts at all. They apply popular tools and techniques, from information technology to process improvements and supplier downsizing, for the purpose of cutting costs to better deal with the increasing stresses of today’s business environment. Such an approach has become popular, presumably because of its relative simplicity and rapid results. Managers can simply delegate individual initiatives to different project managers, who can lead their initiatives with little need for overarching control. Yet this creates the real potential for locking in lag and thereby promoting permanent inflexibility to change—making it more difficult to respond to uncertainty and change.

Tactical Lean: For Better or Worse

The first major challenge is advancing beyond tactical lean—an array of initiatives driven by the general rhetoric of “cutting the fat.” These efforts are marked by widely ranging activities that address problem areas as they present themselves. Major challenges that businesses and institutions face with moving beyond this most basic level of lean maturity include the following:

![]() The tremendous pressure to immediately tackle “low-hanging fruit” drives organizations to focus on immediate problems rather than prioritize actions based on enterprise-wide objectives or needs.

The tremendous pressure to immediately tackle “low-hanging fruit” drives organizations to focus on immediate problems rather than prioritize actions based on enterprise-wide objectives or needs.

![]() Sequencing activities in a way that builds progressively increasing success can be difficult within real-world businesses whose vast complexity and scope present a myriad of potential starting points and challenges.

Sequencing activities in a way that builds progressively increasing success can be difficult within real-world businesses whose vast complexity and scope present a myriad of potential starting points and challenges.

![]() Efforts can suffer a serious loss of support if workers and managers see lean as a superficial fix rather than a means for addressing the more serious challenges that remain.

Efforts can suffer a serious loss of support if workers and managers see lean as a superficial fix rather than a means for addressing the more serious challenges that remain.

![]() Proceeding in a way that locks in inflexibility can backfire by undermining dynamic stability.

Proceeding in a way that locks in inflexibility can backfire by undermining dynamic stability.

As noted in Chapter 3, implementing lean tools as part of a tactical solution can actually represent a step down in the progression to maturity, creating unrecognized costs or new barriers to advancement that might far exceed the savings realized from waste reduction. Conversely, tactical initiatives can offer a critical means for building a baseline of stability from which further advancement can begin. However, it takes tremendous leadership to ensure that these interim solutions do not devolve into a long-term focus for lean activities.

Case Example: Mitigating Uncertainty

Through Tactical Techniques

The Defense Logistics Agency obtains and delivers millions of widely ranging products, from spare parts to food, clothing, and medical supplies, to military customers around the world. These include a range of particularly critical “warstopper” items, whose demand can spike with little or no notice and whose delay could have a tangible impact on its military customers’ mission.

Rather than simply stockpiling massive warehouses of finished inventories that might run out of shelf life or become obscure before they are needed, a team of engineers and specialists evaluates suppliers’ value streams, isolating “choke points” where production flow is constricted. The agency bridges these gaps by working with suppliers to increase equipment capacity, pre-position critical materials or components, and offer technical assistance to enable the speedy production ramp-up to meet emergency needs.2

Earlier this decade, the agency realized that further advancing this effort would take developing the means for more broadly assessing millions of items it manages. It created the Worldwide Web Industrial Capabilities Assessment Program (WICAP), which includes a comprehensive taxonomy for identifying each of millions of unique items based on their underlying processing characteristics (what products they go into and the general capabilities needed for producing them). This provides a point of reference for further investigation in identifying common actions across groups of items—a “leaner” approach for more broadly mitigating the challenges its supplier base faces in preparing for uncertainty.3

For the Defense Logistics Agency, these actions represent an important step forward, slashing the need for billions of dollars of inventory by streamlining its suppliers’ ability to quickly turn out critically needed items during times of crisis. Yet the real challenge comes in applying these tactical lessons to progress to the next levels of lean—leveraging this understanding of how to mitigate suppliers’ challenges and combine items into product families as a means for shifting to a leaner way of operating across its broader business.

Steady-State Lean: A Common Plateau

Steady-state lean offers a starting point for increasing predictability of operations—a foundation for advancing through the hierarchy of lean capabilities as depicted in Figure 6-2. Perhaps the most famous example was Henry Ford’s Model T production line. All evidence indicates that Ford’s buildup of value, from raw materials through his assembly factories, flowed almost seamlessly, giving the appearance that “Ford’s factory was really one vast machine with each production step tightly linked to the next.”4 The result was high quality and extraordinary efficiencies, which led his company to dominate the industry.

What is important, however, is for firms and institutions to recognize this as an interim level; they must maintain their focus on advancing to more advanced levels of maturity in order to avoid running into the same hurdle that Henry Ford faced.

Ford’s genius was in creating an approach that thrived while demand for his Model T expanded, filling a growing customer need. However, while Ford’s approach was tremendously effective when operating within its “special case” of largely predictable, growing demand, the company’s fortunes precipitously declined when the conditions on which it depended later shifted.5

Businesses and institutions today will often need to overcome broader operational disruption in order to lean out assembly lines, fabrication shops, or other activities. A key step for accomplishing this is better synchronizing their production and inventory control system so that it can adequately accommodate current operating conditions. Some might apply information technology solutions to better track inventory across the supply chain, helping to dampen the supply chain effect (the chain reaction described in Going Lean as demand variation is amplified upstream in the supply chain). Doing so can create dramatic results. What these organizations must recognize, however, is that these measures alone will likely do little to create the dynamic dampening capabilities needed to sustain this stability when conditions shift.

Too often, early success leads to complacency. Businesses and institutions tend to focus on stabilizing operations around their initial advances, targeting continuous improvement opportunities to stretch gains even further. Many do not seem to recognize that what they have achieved represents only the tip of the iceberg; moreover, they fail to see that continued transformation is important to mitigating the chance that efforts will be derailed by the changing conditions that will affect them as they progress on their journey.

As Ford ultimately showed, it is not enough to create steady-state efficiencies; doing so without concurrently increasing flexibility across all forms of flow can lead to tremendous problems when conditions ultimately shift.6

Dynamic Lean: The Foundation for Lean Dynamics

Businesses and institutions that have fully embraced the principles of lean dynamics will likely recognize the need for attaining dynamic lean—leveraging lean tools and practices to create an ability to right themselves when things go wrong and maintain internal stability despite uncertain or shifting conditions. At the center of dynamic lean is a deliberate focus on addressing the dynamic challenges within the environment—from understanding and quantifying customers’ changing needs, to better anticipating sudden shifts or crises, to adapting internal methods to promote a steady, efficient response when unforeseen circumstances do emerge.

An up-front dynamic value assessment—the first step within the cycle proposed in Figure 7-1—can establish the baseline understanding for embarking on this course. A key focus is to point out gaps in understanding, identify lag, and determine focal points to guide the transformation. As described in Chapter 6, this should follow a clear structure—first stabilizing operations before focusing attention on creating dynamic stability.

What should the emphasis be? Once stability is attained, efforts can shift from streamlining processes to reconsidering how production planners originally structured the way products and their components are created. Most likely, operations were structured to produce them in a manner that promotes economies of scale under the presumption of stable, predictable demand. A major focus, therefore, should be shifting instead to a product family orientation wherever possible, rather than focusing on improving the way existing processes operate.

Why make this change? As identified in Chapter 4, shifting to manage by product families can create a far-reaching result that could potentially impact many individual value streams that have yet to be mapped, making possible new solutions that otherwise might never have been envisioned.

Other focal points include progressively advancing supplier relationships to promote variation leveling (much as was described with Cessna in Chapter 3, and further described in Going Lean), speeding changeovers (discussed in Chapter 6), applying Total Productive Maintenance measures to reduce disruption from equipment failures, implementing Six Sigma practices to drive down variation in key operations, and designing products and services to foster smooth flow (explained in Chapter 8). This list is not exhaustive; other focal points intended to mitigate the impact of variation with an emphasis on mitigating lag (each of its four forms) should be pursued, based on the results of the dynamic value assessment.

It is important to note that attaining dynamic lean is complicated, in that it takes moving forward simultaneously on multiple fronts, systematically introducing incremental shifts to advance flow to operations, decision making, and information, without breaking the synchronization that can cause disruption along the way. Applying the transformation cycle (depicted in Figure 7-1) offers a means to deal with this by emphasizing localized shifts that advance operational, organizational, and information flow, while creating the broad-based improvements necessary to advance transformational objectives.

Strategic Lean: Bridging Strategy and Execution

Staying competitive in today’s increasingly complex, dynamic business environment means moving beyond a way of thinking that was built around an ideal of consistent, growing mass markets—a condition that no longer exists. Such a mindset has driven a wedge between two basic elements that must work in conjunction to create customer and corporate value: an ability to reach out to customers with new ideas and innovations and an operational efficiency for producing the quality and cost competitiveness that has long restricted innovation. Strategic lean focuses on bridging this gap, leveraging dynamic lean capabilities to bring these factors together and create new opportunities that otherwise would not be possible.

This is precisely what the Garrity Tool Company, a small, private manufacturing company located in Indianapolis, was able to do. During the 2008–2009 economic crisis, the company faced softening markets for some of its offerings (in particular, automotive and aerospace parts). By leveraging its core lean dynamics competencies it quickly shifted directions, increasing business in other, more stable markets, including the production of high-precision medical devices. In doing so, it was able to sustain a largely stable business base, overcoming serious challenges and strengthening its position to advance when business conditions improved.7

Pursuing new business strategies requires drawing on an increased understanding of customers’ dynamic needs, in conjunction with leaner internal capabilities, to create steady, growing value across a broad range of circumstances. They must leverage the flexibility and responsiveness to change that come from developing dynamic lean capabilities, spring-boarding off of these strengths to overcome traditional resistance to change—in sharp contrast to companies that focus largely on opportunities within traditional market segments.

Caution: The Importance of

Looking Outside the Business

Too often, lean initiatives focus on reducing internal wastes, presuming that this will somehow lead to increased customer value. Strategic lean instead focuses on prioritizing resources for incrementally advancing toward a clearer vision of value as defined by the customer. Before focusing on internal improvements, this means beginning by looking outside the business.

![]() Start with the customer. Many businesses and public institutions only generally understand who their customers are as they seek to gain a share of broad market segments. A strategic lean analysis should seek to gain specific insight into customers’ changing needs and desires—with a focus on transforming the market.

Start with the customer. Many businesses and public institutions only generally understand who their customers are as they seek to gain a share of broad market segments. A strategic lean analysis should seek to gain specific insight into customers’ changing needs and desires—with a focus on transforming the market.

![]() Gain insight into the customers’ challenges. A dynamic analysis should begin by assessing how today’s climate of change and uncertainty impacts the business’s customers—making this the starting point for defining value.

Gain insight into the customers’ challenges. A dynamic analysis should begin by assessing how today’s climate of change and uncertainty impacts the business’s customers—making this the starting point for defining value.

![]() Prepare for business uncertainty. Business systems and capabilities are often implemented for anticipated conditions, setting up the organization for crisis and loss when the unexpected ultimately emerges. Scenario planning can provide a helpful starting point for incorporating flexible capabilities to mitigate unforeseen challenges.

Prepare for business uncertainty. Business systems and capabilities are often implemented for anticipated conditions, setting up the organization for crisis and loss when the unexpected ultimately emerges. Scenario planning can provide a helpful starting point for incorporating flexible capabilities to mitigate unforeseen challenges.

![]() Reach for collaborative business opportunities. Creating personalized solutions that meet the customers’ specific needs is a powerful way for leveraging dynamic operational capabilities for building customer loyalty and driving corporate success (described in Chapter 9).

Reach for collaborative business opportunities. Creating personalized solutions that meet the customers’ specific needs is a powerful way for leveraging dynamic operational capabilities for building customer loyalty and driving corporate success (described in Chapter 9).

![]() Map the value curve as a first step for identifying the extent of lag and its impact on responding flexibility to the breadth of business uncertainty and change.

Map the value curve as a first step for identifying the extent of lag and its impact on responding flexibility to the breadth of business uncertainty and change.

Sustainable Lean: Creating Strong, Lasting Value

The ultimate objective for implementing lean dynamics is to attain sustainable lean, a condition marked by value curve excellence. Organizations that have reached this level succeeded in so deeply entrenching the principles of lean dynamics that their value curves—the hallmark of lean—remained virtually flat even in crisis (described in Appendix B). Perhaps more importantly, they succeed in driving a fundamental shift in how leaders view the creation of value for their customers—reaching out to transform the business environment and reshape customer expectations to better value their capabilities.

One difference seems to come from how they manage growth. Consider the example of Southwest Airlines, whose approach runs counter to that of American business culture in that it does not charge ahead to gain market share or seek growth at all costs. Instead, it adheres to a “highly disciplined, self-limited growth rate of 10 to 15 percent per year.”8 Its ability to see beyond traditional measures of business performance allowed Southwest Airlines to avoid the rapid expansion that caused great challenges to even well-known lean benchmarks (even Toyota fell prey to this temptation, to which the company attributed safety problems affecting many of its vehicles that came to light in 2010—a hazard that even mature lean firms can face, as was cautioned in Going Lean). Instead, Southwest’s strong but cautious pace has marked its steady advancement; the company fully evaluates the impact on customer and corporate value before expanding to new markets, and in doing so sustains both corporate and customer value.

What particularly stands out is Southwest’s focus on transforming the business environment, driving a fundamental shift in how value is perceived. The company is recognized even by its peers for creating a tremendous degree of trust with its customers, stating, “They simply trust Southwest to be the best value around.”9 Southwest reaches beyond traditional market expectations; when it enters a new airport, it draws customers from other forms of transportation to substantially expand airline traffic (between 30 and 500 percent), which the U.S. Department of Transportation refers to as “the Southwest effect.” In doing so, it consistently raises the bar for value across the industry, transforming customer expectations in a way that makes its own offerings the gold standard for others to follow.

Key Point: Drawing on a Range of Lean

Capabilities Across All Levels of Maturity

It is only natural to try to associate certain lean tools and practices with specific levels of lean dynamics maturity. However, it is important to differentiate lean dynamics maturity from the capabilities that commonly apply to these levels. Organizations at various levels of maturity are not relegated to using only the tools and techniques that might be associated with a given capability level at any given time; a wide range of tools and practices can be applied simultaneously.

Consider, for instance, the approach for isolating and mitigating “choke points” in a value stream, described in the example of the Defense Logistics Agency’s “warstopper” efforts in the Mitigating Uncertainty Through Tactical Techniques sidebar—a tactical approach for mitigating operational lag and reducing uncertainty and delay in obtaining specific supplies. A company might initially apply this as a way for attaining targeted improvements, essentially supporting its efforts within a tactical level of maturity. But as it advances to higher levels of maturity, these capabilities might continue to offer great value in addressing families of items; their resolution might therefore create an ability to broadly address similar challenges through these now-established product families. Pursuing these tactical actions, in effect, would help expand the reach of these product families’ variation-leveling capabilities and thus support a much higher level of lean maturity.

What distinguishes a company’s or an institution’s level of lean dynamics maturity is not the specific actions it takes but the focus of these actions to progress through normal plateaus and advance to sustainable lean maturity.