The evolution and growth of tourism

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

describe the main characteristics and types of premodern tourism

explain the basic distinctions and similarities between premodern and modern tourism

identify the role of Thomas Cook and the Industrial Revolution in facilitating the modern era of tourism

outline the growth trend of international tourism arrivals since 1950

discuss the primary factors that have stimulated the historical and contemporary demand for tourism

associate evolving patterns of tourism demand with different stages of economic development

identify the social, demographic, technological and political forces that also influence tourism demand.

50

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

The previous chapter considered tourism from a systems approach and described the spatial, temporal and purposive criteria that distinguish international and domestic tourists from other travellers and from each other. Management-related observations were also made about the origin, transit and destination components of the tourism system. Chapter 3 focuses on the historical development of tourism and describes the ‘push’ factors that have stimulated the demand for tourism, especially since the mid-twentieth century.

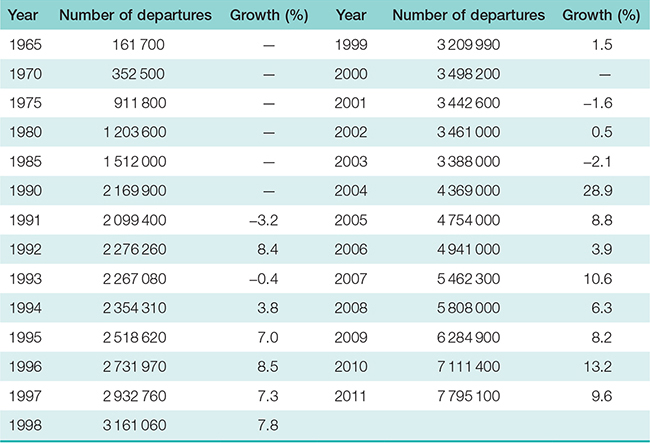

The following section outlines premodern tourism, which is defined for the purposes of this textbook as the period prior to approximately AD 1500 (figure 3.1). Its purpose is to show that while premodern tourism had its own distinctive character, there are also many similarities with modern tourism. Recognition of these timeless impulses and characteristics is valuable to the tourism manager, as they are factors that must be taken into consideration in any contemporary or future situation involving tourism. Moreover, modern tourism would not have been possible without the precedents of Mesopotamia, the Nile and Indus valleys, China, ancient Greece and Rome, the Dark Ages and the Middle Ages. The ‘Early modern tourism (1500–1950)’ section considers the early modern era, which links the premodern to the contemporary period through the influence of the Renaissance and the Industrial Revolution. The ‘Contemporary tourism (1950 onwards)’ section introduces contemporary mass tourism, while the section that follows describes the major economic, social, demographic, technological and political factors that have stimulated the demand for tourism during this era. Australian tourism participation trends are then considered briefly, as well as the future growth prospects of global tourism based on the factors discussed in this chapter.

FIGURE 3.1 Tourism timelines

PREMODERN TOURISM

PREMODERN TOURISM

Mesopotamia, Egypt and the Indus Valley

Mesopotamia, or the ‘land between the rivers’ (situated approximately in modern-day Iraq), is known as the ‘Cradle of Civilisation’ and perhaps the first place to experience tourism. The factors that gave rise to civilisation, and hence to emergent tourism systems, include the availability of a permanent water supply (the Tigris and Euphrates rivers), rich alluvial soils (deposited during the annual flooding of these waterways), a warm climate and a central location between Asia, Africa and Europe, all of which contributed to the development of agriculture. Hunting and gathering societies were replaced by permanent settlements cultivating the same plots of land year after year.51 Surplus food production was a critical outcome of this process, as it fostered the formation of wealth and the emergence of a small leisure class of priests, warriors and others that did not have to worry continually about its day-to-day survival.

The availability of sufficient discretionary time and discretionary income was the most important factor that enabled members of this leisured elite to engage in tourism. Moreover, Mesopotamia was the birthplace of many fundamental inventions and innovations that heralded both the demand and ability to travel for tourism-related purposes. These included the wheel, the wagon, money, the alphabet, domesticated animals such as the horse, and roads. Early cities (another Mesopotamian creation) such as Ur and Nippur were apparently overcrowded and uncomfortable at the best of times, and tourism allowed the elite to escape them whenever possible. Also critical was the imposition of government structure and civil order over the surrounding countryside, which provided a foundation for the development of destination and transit regions (Casson 1994).

Egypt

Mesopotamian civilisation gradually spread to the Nile Valley (in modern-day Egypt) and eastward to the Indus Valley (in modern-day Pakistan), where similar physical environments and factors enabled additional tourism travel. Ancient Egypt provides some of the earliest and most enduring evidence of pleasure tourism. An inscription, carved into the side of one of the lesser known pyramids and dated 1244 BC, is among the earliest examples of tourist graffiti (Casson 1994) and such sites remain foundational to Egypt’s contemporary tourism industry (see Managing tourism: Are Egypt’s pyramids forever?).

managing tourism

![]() ARE EGYPT’S PYRAMIDS FOREVER?

ARE EGYPT’S PYRAMIDS FOREVER?

Survival of some of the world’s oldest and continuously visited tourist attractions is threatened by the realities of contemporary tourism development and the external systems that support and affect this development. The pyramid complex of the Giza Plateau is one of the most culturally significant and recognisable heritage places in the world, and an iconic pillar of the Egyptian tourism industry. High levels of visitation, however, are having negative direct and indirect effects on these antiquities. Most directly relevant has been the deterioration of interior pyramid sites through exposure to chemicals in the sweat and breath of tourists. In many cases, this has required closures and expensive restoration efforts. Indirect tourism effects include the development of adjacent squatter settlements housing tourism workers and their families, which contribute to air pollution that causes chemical decomposition of exteriors (especially of the Sphinx), rising and heavily contaminated ground water that threatens the foundations of major structures, and aesthetic intrusions on the grandeur of the complex (Shetawy & El Khateeb 2009). Proposed strategies to cope with tourism-related stresses have included a ring-road around the plateau to limit direct exposure to vehicles and their emissions, the banning of horses and camels within the core pyramid area, and the construction of visitor centres and picnic areas to divert visitors and locals away from that core. A much bigger issue, however, is relentless 52 urban sprawl from the adjacent city of Cairo, home to over 15 million residents in 2014. The air pollution, industrial development and water contamination associated with this sprawl threatens to overwhelm the plateau regardless of the measures taken to control tourism (Vaz, Caetano & Nijkamp 2011). That no comprehensive management plan has yet been implemented is partly explained by the ongoing Arab Spring revolution, which has focused attention on the national political situation. Ironically, it has also reduced stress from tourism due to decreased visitor numbers.

China

Impulses of civilisation emerged in China around the same time as they did in Mesopotamia. Whether this was coincidental or influenced by the latter region is unclear. Regardless, it is known that tourism-related travel was well established by 2000 BC and that four distinct groups were dominant throughout the premodern era (Guo, Turner & King 2002). The first group consisted of royalty, their security and their entourages. One reason for travel was to demonstrate government authority and learn more about conditions in different parts of the empire. Another reason was to shift the seat of the royal residence between cooler summer and warmer winter locations. Given the massive number of individuals involved in such transfers, the royal residences became resorts of a sort and centres for leisure pursuits such as hunting and horseback riding. The second group involved scholars, students and artists, reflecting a long Chinese Confucian tradition of respect for education, learning and self-improvement. Various scenic and inspiring locations in the mountains and elsewhere became popular destinations, and the writings, poems and paintings produced by visitors may be seen as an early form of travel literature and destination promotion. Buddhist pilgrims and monks comprised a third major group, and their travel to numerous sacred sites within China was complemented by travel to Buddhist sites in India — some of the earliest indications of outbound tourism. Finally, premodern China was characterised by extensive business travel by traders, though the links here to tourism per se are perhaps more tenuous.

The sophisticated civilisation of premodern China was a great facilitator of tourism activity, although there were also extensive periods of instability that dissuaded travel. As early as fifth century BC, the Grand Canal accommodated travel between north and south China for all four groups, while the Silk Road network of routes connected China with Persia, India and the Middle East. During the Tang Dynasty (c. AD 600–900), China was arguably the centre of world tourism. The capital city of Xi’an had a population of at least two million (Terrill 2003) and at any time hosted a large population of foreign students and other visitors.

Ancient Greece and Rome

Tourism in ancient Greece is mostly associated with national festivals such as the Olympic Games, where residents of the Greek city–states gathered every four years to hold religious ceremonies and compete in athletic events and artistic performances. The participants and spectators at this festival, estimated to number in the tens of thousands, would have had little difficulty in meeting the modern criteria for international stayovers. Accordingly, the game site at Olympia can be considered as one of the oldest specialised, though periodic, tourist resorts, and one that like the Egyptian pyramids still attracts the attention of tourists (see Technology and tourism: New ways to see old Olympia). The Games themselves are one of the first recorded examples of sport and event tourism and the precursor to the modern Olympics (Toohey & Veal 2007).

53The transit process in ancient Greece was not pleasant or easy. Although a sacred truce was called during the major festivals, tourists were often targeted by highway robbers or pirates, depending on their mode of travel. Roads were primitive and accommodation, if available, was rudimentary, unsanitary and often dangerous. It is useful to point out that the word ‘travel’ is derived from the French noun travail, which translates into English as ‘hard work’. As with the Mesopotamians, Egyptians and Chinese, the proportion of ancient Greeks who could and did travel as tourists was effectively restricted to a small elite. However, the propensity to engage in tourism was socially sanctioned by the prevalent philosophy of the culture (applicable at least to the elite), who valued leisure time for its own sake as an opportunity to engage in artistic, intellectual and athletic pursuits (Lynch & Veal 2006).

technology and tourism

![]() NEW WAYS TO SEE OLD OLYMPIA

NEW WAYS TO SEE OLD OLYMPIA

The site of the ancient Olympic Games in Greece remains an enduring cultural icon of the Western world despite consisting only of ruins. Numerous tourists continue to visit the site, but people now have the opportunity to better appreciate the original qualities of Olympia through the use of virtual reality (VR) technology. In Athens, several immersive VR exhibits have been developed for visitors to the Foundation of the Hellenic World (www.fhw.gr/fhw/), an institute dedicated to preserving and disseminating ancient Greek history and culture. Applications of new information technologies are central to its mission. One of the exhibits in the Foundation’s Cultural Centre is A Walk through Ancient Olympia, which depicts the site as historians believe it to have appeared at the end of the second century BC. Featured attractions include the Temple of Zeus, the stadium and various ancient rituals. This and other productions can be viewed in several venues including the Tholos, which is a VR theatre that resembles a planetarium and accommodates 130 viewers. Special glasses are worn to create a 3D effect, which is amplified by wrap-around screens, and a sole viewer can navigate the virtual site via hand controllers. The main advantage of VR is the opportunity to experience the semblance of an original site that no longer exists. In some venues, viewers can create their own individualised tours, while researchers can enhance the authenticity of these tours by using VR simulators to test theories such as whether a certain ruined structure originally supported a particular kind of roof. Some argue that VR experiences provide a surrogate for an actual site visit, thereby reducing environmental impacts from excessive visitation. Others, however, suggest that high-quality VR exposure might inspire viewers to visit the site to obtain another perspective, thereby increasing the environmental stress (Guttentag 2010).

Rome

With its impressive technological, economic and political achievements, ancient Rome (which peaked between 200 BC and AD 200) was able to sustain unprecedented levels of tourism activity that would not be reached again for another 1500 years. An underlying factor was the large population of the Roman Empire. While the elite class was only a fraction of the 200 million-strong population, it constituted a 54large absolute number of potential tourists. These travellers had a large selection of destination choices, given the size of the Empire, the high level of stability and safety achieved during the Pax Romana (Roman Peace) of its peak period, and the remarkably sophisticated network of Roman military roads (many of which are still used today) and associated rest stops. By AD 100 the Roman road network extended over 80 000 kilometres (Casson 1994).

The Roman tourism experience is surprisingly modern in its resonance. Fuelled by ample discretionary time and wealth, the propensity of the Roman elite to travel on pleasure holidays gave rise to an ‘industry’ of sorts that supplied souvenirs, guidebooks, transport, guides and accommodation. The number of specialised tourism sites and destinations also increased substantially. Famous Roman resorts included the town of Pompeii (destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79), the spas of the appropriately named town of Bath (in Britain), and the beach resort of Tiberius, on the Sea of Galilee. Second homes, or villas, were an important mode of retreat in the rural hinterlands of Rome and other major cities. Wealthy Romans often owned villas in a seaside location as well as the interior, to escape the winter cold and summer heat, respectively, of the cities. Villas were clustered thickly around the Bay of Naples during the first century AD, and those Romans wealthy enough to travel a long distance were especially attracted to the historical sites of the Greeks, Trojans and Egyptians.

The Dark Ages and Middle Ages

The decline and collapse of the Roman Empire during the fifth century AD severely eroded the factors that facilitated the development of tourism during the Roman era. Travel infrastructure deteriorated, the size of the elite classes and urban areas declined dramatically, and the relatively safe and open Europe of the Romans was replaced by a proliferation of warring semi-states and lawless frontiers as barbarian tribes occupied what was left of the Roman Empire. Justifiably, this period (c. 500–1100) is commonly referred to as the Dark Ages. The insularity to which Europe descended during this period is evident in contemporary world maps that feature wildly distorted cartographic images dominated by theological themes (e.g. Jerusalem at the centre of the map) and oversized town views that reveal no practical information for the would-be traveller. Travel was no doubt dissuaded by the grotesque creatures that were believed to inhabit remote regions (see figure 3.2).

FIGURE 3.2 Popular medieval monsters

The social, economic and political situation in Europe recovered sufficiently by the end of the eleventh century that historians distinguish the emergence of the Middle Ages around this time (c. 1100–1500). Associated tourism phenomena include the Christian pilgrimage, stimulated by the construction of the great cathedrals and the consolidation of the Roman Catholic Church as a dominant power base and social influence in Europe. The pilgrimages of the Middle Ages (popularised in the writings of English author Geoffrey Chaucer) are interesting to tourism researchers for several reasons:

Even the poorest people were participants, motivated as they were by the perceived spiritual benefits of the experience.

55Because of these perceived spiritual benefits, many pilgrims were willing to accept (and even welcomed) a high level of risk and suffering.

At the same time, the opportunity to go on a pilgrimage was welcomed by many for the break it provided from the drudgery of daily life.

Another major form of travel, the Crusades (1095–1291), also contributed to the development of the premodern travel industry, even though the Crusaders themselves were not tourists, but soldiers who wanted to free the Holy Land from Muslim control. Religiously inspired like the pilgrims, the Crusaders unwittingly exposed Europe once again to the outside world, while occasionally engaging in tourist-like behaviour (e.g. souvenir collecting, sightseeing) during their journeys.

EARLY MODERN TOURISM (1500–1950)

EARLY MODERN TOURISM (1500–1950)

Europe began to emerge from the Middle Ages in the late 1300s, assisted by the experience of the Crusades and later by the impact of the great explorations. By 1500 the Renaissance (literally, the ‘rebirth’) of Europe was well under way, and the world balance of power was beginning to shift to that continent, marking the modern era and the period of early modern tourism. Ironically, tourism in China after 1500 experienced a five-century period of decline as Ming Dynasty and successive rulers became more China-focused and xenophobic.

The Grand Tour

The Grand Tour is a major link between the Middle Ages and contemporary tourism. The term describes the extended travel of young men from the aristocratic classes of the United Kingdom and other parts of northern Europe to ‘classical’ Europe for educational and cultural purposes (Towner 1996). A prevailing ‘culture of travel’ encouraged such journeys and spawned a distinctive literature as the literate young participants usually kept diaries of their experiences. It is therefore possible to reconstruct this era in detail. We know, for example, that the classical Grand Tours first became popular during the mid-sixteenth century, and persisted (with modification) until the mid-nineteenth century (Withey 1997).

While there was no single circuit or timeframe that defined the Grand Tour, certain destinations feature prominently in written accounts. Paris was usually the first major destination of the Tourists (authors’ italics), followed by a year or more of visits to major Italian cities such as Florence, Rome, Naples and Venice (Towner 1996). Though the political and economic power of the Italian peninsula was in decline by the early 1600s, these centres were still admired for their Renaissance and Roman attractions, which continued to set the cultural standards for Europe. A visit to these cultural centres was vital for anyone aspiring to join the ranks of the elite in their home countries. The journey back to northern Europe usually took the traveller across the Swiss Alps, through Germany and into the Low Countries (Flanders, The Netherlands) where the Renaissance flowered during the mid-1600s.

According to Towner (1996) about 15 000–20 000 members of the British elite were abroad on the Grand Tour at any time during the mid-1700s. Wealthier participants might be accompanied by an entourage of servants, guides, tutors and other retainers. Towards the end of the era, the emphasis in the Grand Tour shifted from the aristocracy to the more affluent middle classes, resulting in a shorter stay within fewer destinations. Other destinations, such as Germany and the Alps, also became more 56popular. The classes from which the Grand Tour participants were drawn accounted for between 7 and 9 per cent of the United Kingdom’s population in the eighteenth century.

Motives also shifted throughout this era. The initial emphasis on education, designed to confer the traveller with full membership into the aristocratic power structure and to make important social connections on the continent, gradually gave way to more stress on simple sightseeing, suggesting continuity between the classical Grand Tour and the backpacker of the modern era. Whether as an educational or sight-seeing phenomenon, however, the Grand Tour had a profound impact on the United Kingdom, as cultural and social trends there were largely shaped by the ideas and goods brought back by the Grand Tourists. These impacts were also felt at least economically in the destination regions through the appearance of the souvenir trade and tour guiding within major destination cities. Further indication of tourism’s timeless tendency to foster business opportunity was the first appearance in the 1820s of the practical travel guide, directed toward would-be Grand Tourists (Withey 1997).

Spa resorts

The use of hot water springs for therapeutic purposes, and hence medical tourism, dates back at least to the ancient Greeks and Romans (e.g. the spas at Bath in the United Kingdom) (Casson 1994). Established in the Middle Ages by the Ottoman Empire within its European possessions, several hundred inland spas served wealthy visitors in continental Europe and the United Kingdom by the middle of the nineteenth century. Many, however, were small and did not survive as destinations. Others, such as Karlsbad (in the modern-day Czech Republic), Vichy (in France) and Baden-Baden (in Germany), were extensive and are still functioning as spas (Towner 1996). The availability of accessible and suitable water was the most important factor in influencing the establishment, character and size of spas, though proximity to transportation, urban areas and related amenities and services were also influential. In contemporary times, larger hotels are increasingly likely to offer spa-type facilities as a form of product diversification that provides a lucrative supplementary revenue stream (Mandelbaum & Lerner 2008).

Seaside resorts

By the early 1800s tourism opportunities were becoming more accessible to the lower classes of the United Kingdom and parts of western Europe. This was a result of the Industrial Revolution, which transformed the region (beginning in England during the mid-1700s) from an agrarian society to one that was dominantly urban and industrial. Crowded cities and harsh working conditions created a demand for recreational opportunities that would take the workers, at least temporarily, into more pleasant and relaxing environments. Domestic seaside resorts emerged in England to fulfil this demand, facilitated by the location of all large population centres within 160 kilometres of the English coast. Interestingly, many seaside resorts began as small and exclusive communities that catered, like the inland spas, only to the upper classes.

A stimulus for travelling to the coast was the belief, gaining in popularity by the mid-eighteenth century, that sea bathing, combined with the drinking of sea water, was an effective treatment for certain illnesses. The early seaside resorts therefore demonstrate continuity between the classic spa era described earlier and modern hedonistic mass tourism at beach locations. Seaside resorts such as Brighton and Scarborough 57soon rivalled inland spa towns such as Bath as tourist attractions, with the added advantage that the target resource (sea water) was effectively unlimited, and the opportunities for spatial expansion along the coast were numerous.

A primary factor that made the seaside resorts accessible to the working classes was the construction of railways connecting these settlements to nearby large industrial cities. During the 1830s and 1840s, this had the effect of transforming small English coastal towns into sizeable urban areas, illustrating how changes in a transit region can produce fundamental change in a destination region. As the Industrial Revolution spread to the European mainland and overseas to North America and Australia, the same demands were created and the same processes repeated. The well-known American seaside resort of Atlantic City traces its origins as a working-class seaside resort to the construction of a rail link with Philadelphia in the 1850s, and subsequent expansion to the novelty effect of impressively large and comfortable hotel facilities (Stansfield 2005). In Australia, seaside resorts such as Manly, Glenelg and St Kilda were established in the late nineteenth century to serve, respectively, the growing urban areas of Sydney, Adelaide and Melbourne.

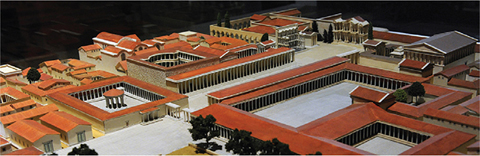

The progression of the Industrial Revolution in England and Wales coincided with the diffusion of seaside resorts to meet the growing demand for coastal holidays. Figure 3.3 depicts their expansion from seven in 1750 to about 145 by 1911, at which time most sections of the coastline had at least one resort (Towner 1996). This pattern of diffusion, like the growth of individual resorts, was largely a haphazard process unassisted by any formal management or planning considerations. Many British seaside resorts today, in part because of this poorly regulated pattern of expansion, are stagnant or declining destinations that need to innovate in order to revitalise their tourism product (see Chapter 10).

FIGURE 3.3 Pattern of seaside resort diffusion in England and Wales, 1750–1911

Source: Towner (1996, p. 179)

58

Thomas Cook

Along with several contemporaries from the mainland of Europe, Thomas Cook is associated with the emergence of tourism as a modern, large-scale industry, even though it would take another 150 years for mass tourism to be realised on a global scale. As a Baptist preacher concerned with the ‘declining morals’ of the English working class, Cook conceived the idea of chartering trains at cheap fares to take workers to temperance (i.e. anti-alcohol) meetings and bible camps in the countryside. The first of these excursions, provided as a day trip from Leicester to Loughborough on 5 July 1841, is sometimes described as the symbolic beginning of the contemporary era of tourism. Gradually, these excursions expanded in the number of participants and the variety of destinations offered. At the same time, the reasons for taking excursions shifted rapidly from spiritual purposes to sightseeing and pleasure. By 1845 Cook (who had by then formed the famous travel business Thomas Cook & Son) was offering regular tours between Leicester and London. In 1863 the first international excursion was undertaken (to the Swiss Alps), and in 1872 the first round-the-world excursion was organised with an itinerary that included Australia and New Zealand. The Cook excursions can be considered the beginning of international tourism in the latter two countries, although such trips remained the prerogative of the wealthy. By the late 1870s, Thomas Cook & Son operated 60 offices throughout the world (Withey 1997).

Arrangements for the Great Exhibition of 1851, held in London, illustrate the innovations that Thomas Cook & Son introduced into the tourism sector. The 160 000 clients who purchased his company’s services (accounting for 3 per cent of all visitors to the Exhibition) were provided with:

an inclusive, prepaid, one-fee structure that covered transportation, accommodation, guides, food and other goods and services

organised itineraries based on rigid time schedules

uniform products of high quality

affordable prices, made possible by the economies of scale created through large customer volumes.

The genius of Thomas Cook & Son, essentially, was to apply the production principles and techniques of the Industrial Revolution to tourism. Standardised, precisely timed, commercialised and high-volume tour packages heralded the ‘industrialisation’ of the sector and the reduction of many of its inherent risks. Thus, while the development of the seaside resorts was a mainly unplanned phenomenon, Thomas Cook can be described as an effective entrepreneurial pioneer of the industry who fostered and accommodated the demand for these and other tourism products. The actual connection between supply and demand, however, was only made possible by communication and transportation innovations of the Industrial Revolution such as the railway, the steamship and the telegraph, which the entrepreneur Cook used to his advantage. As a result of such innovative applications, Thomas Cook & Son exposed an unprecedented pool of potential travellers (i.e. an increased demand) to an unprecedented number of destinations (i.e. an increased supply). Today, the package tour is still one of the fundamental, taken-for-granted symbols of the contemporary large-scale tourism industry.

The post-Cook period (1880–1950)

Due to the widespread adaptation of Industrial Revolution technologies and principles to the travel industry, tourism expanded significantly from the 1870s onwards. Much of this growth was initially concentrated in the domestic sector of the more industrialised regions such as the United States, western Europe and Australia. The American 59west, for example, experienced a period of rapid tourism growth associated first with the closing of the frontier in the 1890s and then with the increase in car ownership (Gunn 2004). Domestic tourism also flourished in the United Kingdom, and by 1911 it was estimated that 55 per cent of the English population were making day excursions to the seaside, while 20 per cent travelled there as stayovers (Burton 1995).

International tourism growth in the post-Cook period of the early modern era was less robust than in the domestic tourism sector. This was due in part to outbound travel for the middle and working classes only being feasible where countries shared an accessible common border, as between Canada and the United States, and between France and Belgium. Switzerland, for example, which shared frontiers with several major countries, received about one million tourists annually by 1880 (Withey 1997). In addition, the period between 1880 and 1950 was characterised by four events that drastically curtailed international tourism. The first of these was the global depression of the 1890s, and this was followed two decades later by World War I (1914–18). Resumed tourism growth in the 1920s was subsequently curtailed by the Great Depression of the 1930s and World War II (1939–45). No wars or economic downturns of comparable magnitude, however, have thus far interrupted the expansion of the tourism industry since the end of World War II.

CONTEMPORARY TOURISM (1950 ONWARDS)

CONTEMPORARY TOURISM (1950 ONWARDS)

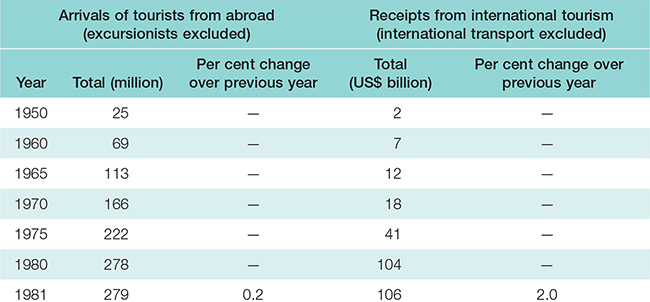

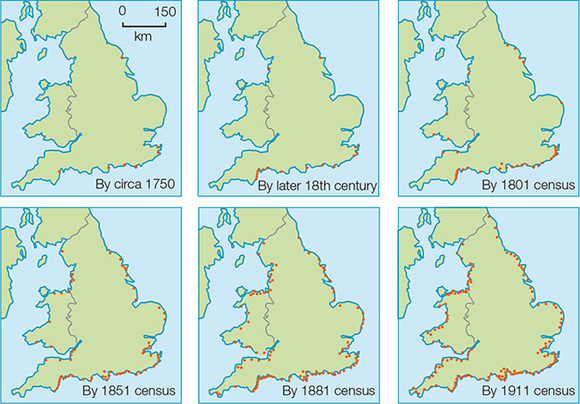

The rapid growth of tourism during the contemporary era of modern mass tourism is reflected in the global trend of inbound tourist arrival and associated revenues (see table 3.1). The statistics from the 1950s and 1960s are speculative due to the irregular nature of data collection at that time (see Chapter 1). But even allowing for a substantial margin of error, an exponential pattern of growth is readily evident, with inbound stayovers increasing 40-fold between 1950 and 2012, from an estimated 25 million to about one billion. International tourism receipts have grown even more dramatically over the same period, from US$2 billion to over US$ one trillion. An aspect of table 3.1 that is worth noting is the consistent pattern of growth, interrupted only by the economic recession of the early 1980s, the terrorist attacks of 2001, the combined effects of the Iraq War and the SARS epidemic in 2003, and the global financial crisis of 2008 and beyond.

The world’s biggest industry?

Interest groups such as the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) maintain that tourism is the world’s single largest industry, accounting directly and indirectly in 2012 for approximately one of every ten jobs and 10 per cent of all economic activity as noted in Chapter 1. Whether this does indeed constitute the world’s biggest industry, however, depends on how it is classified and quantified, what it is compared against, and indeed whether it can legitimately be regarded as a single industry (see Chapter 1).

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH INCREASED TOURISM DEMAND

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH INCREASED TOURISM DEMAND

Many of the generic factors that influence the growth of tourism have been introduced briefly in the earlier sections on the evolution of tourism. This section focuses specifically on those factors that have stimulated the demand for tourism (or push factors), especially since 1950. Although outlined under the following five separate headings, the factors are interdependent and should not be considered in isolation.

Economic factors

Affluence is the most important economic factor associated with increased tourism demand. Normally, the distribution and volume of tourism increases as a society becomes more economically developed and greater discretionary household income subsequently becomes available. Discretionary household income is the money available to a household after ‘basic needs’ such as food, clothing, transportation, education and housing have been met. Such funds might be saved, invested or used to purchase luxury goods and services (such as a foreign holiday or expensive restaurant meal), at the ‘discretion’ of the household decision makers. Average economic wealth is commonly, if imperfectly, measured by per capita gross national product (GNP), or the total value of all goods and services produced by a country in a given year, divided by the total resident population. It is also important, however, to consider how equitably this wealth is distributed. A per capita GNP of $10 000 could indicate that everyone each makes $10 000 or that each member of just a small elite makes much more than this while most people remain in poverty. The latter scenario greatly constrains the number of potential tourists, and is essentially the structure that prevailed in the premodern era.

In the early stages of the development process, regular tourism participation (and pleasure tourism in particular) is feasible only for the elite, as demonstrated by the history of tourism prior to Thomas Cook. In all subsequent stages, every society possesses a small elite that continues to travel extensively compared with other residents. As of the early 2000s, there were only a few societies that still demonstrated a level of economic development comparable to Europe before the Industrial Revolution. In her tourism participation sequence, Burton (1995) refers to these pre-industrial, mainly agricultural and subsistence-based situations as Phase One (table 3.2).

In Phase Two, the generation of wealth increases and spreads to a wider segment of the population as a consequence of accelerating industrialisation and related processes such as urbanisation. This happened first in the United Kingdom, and then elsewhere, during the Industrial Revolution. At present, China is roughly at the same stage of development as that which England passed through during the first half of the twentieth century and is similarly experiencing an explosion in demand for domestic tourism that is fuelling the development of seaside resorts and other tourism facilities. From 62being almost non-existent in the early 1970s, domestic tourism in China expanded to an estimated 639 million domestic tourist arrivals in 1996 to 870 million in 2003 and 3.13 billion in 2012 (Chinatraveltrends.com 2012). Concurrently, an ever-increasing number of nouveau riche, or newly rich individuals, are visiting an expanding array of foreign destinations.

TABLE 3.2 Burton’s four phases of tourism participation

| Phase | Context | Tourism participation (in all stages, small elite travels extensively) |

| Phase One: Pre-industrial |

|

|

| Phase Two: Industrialising |

|

|

| Phase Three: Industrialised |

|

|

| Phase Four: Post-industrial |

|

|

By Phase Three, the bulk of the population in the industrialised society is relatively affluent, leading to further increases in mass domestic travel as well as mass international tourism to nearby countries. This began to occur in the United Kingdom in the early 1960s, and will likely characterise China within the next 10–20 years. In 2012, 82 million Chinese travelled abroad (a 100 per cent increase over 2007), an impressive figure suggesting Phase Three dynamics until one realises that this represents only about 6 per cent of the population and overwhelmingly involves travel to the adjacent Chinese-controlled territories of Hong Kong and Macau (Chinatraveltrends.com 2012).

Finally, Phase Four represents a fully developed post-industrial country with widespread affluence, and a subsequent pattern of ubiquitous participation in domestic tourism as well as mass international tourism to a diverse array of short- and long-haul destinations. The major regions and countries included in this category are western Europe (including the United Kingdom), the United States and Canada, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore, Israel, Australia and New Zealand. These origin regions have a combined population of approximately 850 million, or 12 per cent of the world’s population, but account for roughly 80 per cent of all outbound tourist traffic. The so-called BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) are expected to attain Phase Four dynamics within the next two or three decades, and this will have significant social, cultural, environmental and economic implications for the world (BRICS forum 2013).

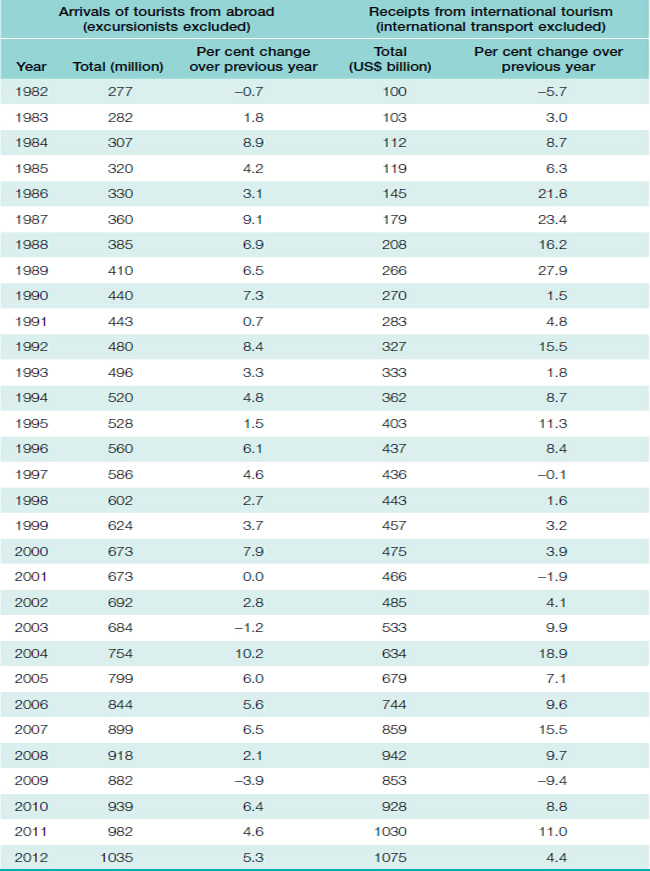

Increasing income and expenditure in Australia

The emergence of a prosperous Australian population during the past century mirrors Australia’s transition from Phase Two to Phase Four status. Consumption expenditures are a good if partial indicator of living standards, as they show to what extent individuals are able to meet their material needs and wants through the purchase of attendant goods and services. Per capita consumption expenditures in Australia were 63stable or declined slightly until the late 1930s, due in part to the effects of World War I and the Great Depression. Large increases occurred after World War II, and by 2003–04, these expenditures were about three times higher than the 1938–39 levels (and also the 1900 levels) in ‘real’ terms — that is, after controlling for inflation. Significantly from a tourism perspective, expenditures on ‘travel’ increased in similar proportion from 3.6 per cent of the total in 1900 to 11.6 per cent in 2003–04 (Haig & Anderssen 2007). As depicted in figure 3.4, household consumption expenditures in Australia continued to rise steadily in real terms during the early 2000s, increasing by 15.2 per cent between 2003 and 2011. This was largely the consequence of revenues earned from providing minerals and other raw materials to the booming Chinese economy. Such growth, however, also needs to be qualified by rising levels of household debt.

Social factors

Major social trends that have influenced participation in tourism include the increase in discretionary time, its changing distribution, and shifts in the way that society perceives this use of time. During Phase One, the rhythm of life is largely dictated by necessity, the seasons and the weather. Formal clock time has little or no meaning as nature imposes its own discipline on human activity. People in this phase are ‘task oriented’ rather than ‘time oriented’, and no fine lines are drawn between notions of ‘work’, ‘rest’ or ‘play’.

The effect of industrialisation is to introduce a formalised rigour into this equation. Phase Two societies are characterised by an increasingly orchestrated system wherein discrete notions of work, leisure and rest are structured into rigorous segments of clock time, and the life rhythm is regulated by the factory whistle and the alarm clock rather than the rising or setting of the sun. Young (usually male at first) adults are expected to enter the labour force after a short period of rote education, and then to retire after a specified period of formal workplace participation. The structure that most symbolises this industrial regime is the division of the day into roughly equal portions of work, rest and leisure activity, with the latter constituting the discretionary time component (Lynch & Veal 2006). Leisure and rest time are not generally seen as important in their own right, but as a necessary interruption to the work schedule to maintain the labourer’s efficiency. The Phase Two industrialising era can therefore be said to be dominated by a ‘play in order to work’ philosophy.

Ironically, the early stages of industrialisation often produce a substantial increase in the amount of time spent at work. For example, the average European industrial labourer by the mid-1800s worked a 70-hour week (or 4000 hours per year), with 64the weekly work routine interrupted only by the Sunday day of rest. Since then, the situation has improved dramatically in conjunction with the transition to Phases Three and Four. The average working week for the European labour force declined to 46 hours by 1965 and 39 hours by the 1980s. Australia, however, was the first country to institute a standard eight-hour working day (Lynch & Veal 2006). The difference in available discretionary time in Australia between the beginning and end of the twentieth century is illustrated by the observation that 44 per cent of time for an average Australian male adult born in 1988 is discretionary, compared with 33 per cent for one born in 1888. As of November 2012, the average time actually worked in any given week was 33.8 hours (ABS 2013).

While the reduction in the amount of working time has clear positive implications for the pursuit of leisure activities in general, the changing distribution of this time is also important to tourism. One of the first major changes was the introduction of the two-day weekend, which was instrumental in making stayover tourism possible to nearby (usually domestic) locations. Before this, tourism for most workers was limited to daytime Sunday excursions. A second major change was the introduction of the annual holiday entitlement. Again, Australia was a pioneer, being one of the first countries to enact legislation to create a four-week holiday standard. The pressure for such reform, surprisingly, came not only from the labour movement, but also from corporations aware that the labour force required more discretionary time to purchase and consume the goods and services they were producing (Lynch & Veal 2006). It can be said therefore that the transition to the more mature phases of economic development is accompanied by the increasing importance of consumption over production in terms of time allocation. In any event, the growing holiday portion of the reduced working year has made longer domestic and international holidays accessible to most of the population.

Flexitime and earned time

More recently, the movement of the highly developed Phase Four countries into a technology- and information-oriented post-industrial era has resulted in innovative work options that are eroding the rigid nine-to-five type work schedules and uniform itineraries of industrial society. The best known of these options is flexitime, which allows workers, within reason, to distribute their working hours in a manner that best suits their individual lifestyles. Common flexitime possibilities include three 12-hour days per week followed by a four-day weekend, or a series of 40-hour working weeks followed by a two-month vacation.

Earned time options are production rather than time-based. They usually involve the right to go on vacation leave once a given production quota is met. If, for example, a worker meets an annual personal production target of 1000 units by 10 August, then the remainder of the year is vacation time, unless the individual decides (and is given the option) to work overtime to earn additional income. Such time management innovations have important implications for tourism, in that lengthy vacation time blocks are conducive to extended long-haul trips and increased tourism participation in general.

Changing attitudes

Social attitudes towards leisure time are also changing in the late industrial, early post-industrial period. As in ancient Greece, leisure is generally seen not just as a time to rest between work shifts, but as an end in itself and a time to undertake activities such as foreign travel, which are highly meaningful to some individuals. This change in perception is consistent with the increasing emphasis on consumption over production. In contrast to the industrial era, a ‘work in order to play’ philosophy (i.e. working 65to obtain the necessary funds to undertake worthwhile leisure pursuits) is emerging to provide a powerful social sanctioning of most types of tourism activity.

Beyond sanctioning, tourism is also increasingly perceived as a basic human right. Article 7 of the 1999 World Tourism Organization Global Code of Ethics for Tourism, for example, affirms the right to tourism and emphasises that ‘obstacles should not be placed in its way’, since ‘the prospect of direct and personal access to the discovery and enjoyment of the planet’s resources constitutes a right equally open to all the world’s inhabitants’ (see Breakthrough tourism: Getting a break through social tourism). A related issue, however, is the tendency of many individuals to spend a growing portion of their discretionary time in additional work activity to maintain a particular lifestyle or to repay debts, thereby constraining their opportunities for engaging in tourism or other leisure activities. Similarly, employees in Australia and other economically developed countries are notorious for stockpiling their recreational leave time (see Contemporary issue: No Leave, No Life).

breakthrough tourism

![]() GETTING A BREAK THROUGH SOCIAL TOURISM

GETTING A BREAK THROUGH SOCIAL TOURISM

The idea that leisure travel is an important aspect of personal and collective wellbeing, and also a basic human right, is gaining traction through government-sponsored programs that help members of disadvantaged population groups to take a holiday. Current examples from Europe, which dominate this phenomenon of social tourism, include the Flanders region of Belgium, where over 100 000 families have been given holiday discounts by travel industry partners. In Spain, the government offered a free seaside holiday to over one million elderly citizens during the 2008–09 tourism season (Simpson 2012a). The European Commission’s Calypso program, trialled from 2009–11, allowed persons with disabilities, youth (aged 18–30), lower-income families and seniors to have a holiday experience by facilitating connections between participants and providers. Notably, this program not only tried to increase participant wellbeing, but also sought to promote economic development by restricting these holidays to the low season, and to build geopolitical stability within the European Union by focusing on intercultural contacts through cross-border travel (European Commission 2012). According to some claims, each euro invested by government in social tourism can yield four euros in taxes, expenditures and other benefits (Minnaert, Maitland & Miller 2011). In most cases, the target groups are offered the same basic experience as other tourists, but some initiatives are more specialised. For example, the UK social charity Break maintains four holiday centres where specialist staff and facilities are available to cater for children with learning and other disabilities (Minnaert, Maitland & Miller 2011). In all cases, social tourism raises the moral issue of whether tourism is a right or a privilege. Influential bodies such as the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) argue that it is a right for all people, yet concurrently designate it as a discretionary activity. Social tourism also raises the question as to what obligations the more privileged segments of society have to the less privileged segments, and whether some disadvantaged persons (e.g. those laid off from employment) are more deserving of support than others (e.g. those who refuse to look for employment).

contemporary issue

![]() NO LEAVE, NO LIFE

NO LEAVE, NO LIFE

Overworked Australians not only compromise their own physical and mental wellbeing; they create major financial liability issues for companies (126 million days of stockpiled annual leave as of late 2012) and contribute to an underperforming domestic tourism sector. In response, Tourism Australia, the peak national destination marketing body, introduced the long-term No Leave, No Life campaign (www.noleavenolife.com) to encourage holiday taking. Aimed mainly at businesses, the campaign provides web-based tools that help the employer to profile typical stockpiler employees (characteristically accounting for one in four employees), understand and address underlying reasons for stockpiling, encourage (rather than force) employees to take accrued leave, and ultimately change corporate culture to make it more leave-friendly. Frequent short breaks are encouraged, not just because of their more positive workplace implications, but also because they are more conducive to domestic than outbound tourism. Executives are encouraged to lead by example. Beeton (2012) contends that this marketing campaign, unusual in its focus on ‘push’ rather than ‘pull’ factors to stimulate domestic tourism in Australia, has a high probability of succeeding if it can change the salient workplace beliefs of stockpilers. Common reasons for not taking leave, for example, include the normative perceptions that it is a sign of weakness, causes more work for others and is inconsistent with the internal work culture. Personal attitudes of stockpilers include the belief that leave is an impediment to moving up the corporate ladder. Also notable are preferences to keep working, a desire to stockpile time for a really big future trip and/or fears of being bored during leave time. Such attitudes can be challenged by pointing out the correlation between taking leave and higher productivity, allocating leave in between projects or during slower business periods, and removing perceived penalties for being absent from work. It is also recommended that 4 weeks of leave be factored into business-planning processes so that it becomes normative, and that objectives be set based on a 48-week work plan.

Demographic factors

The later stages of the development process (i.e. Phases Three and Four) are associated with distinctive demographic transformations, at least four of which appear to increase the propensity of the population to engage in tourism-related activities.

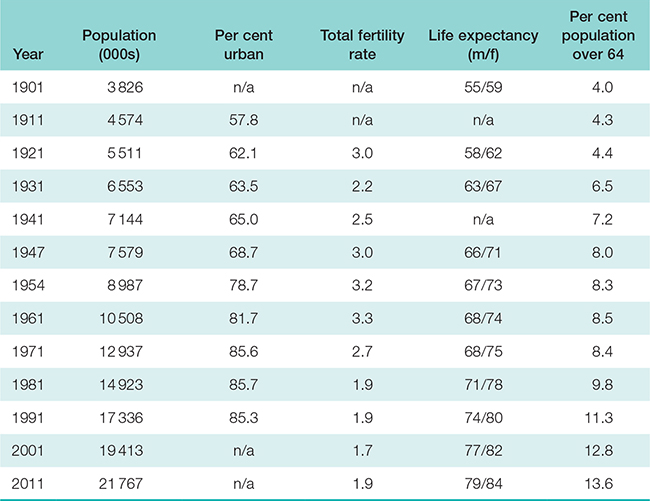

Reduced family size

Because of the costs of raising children, small family size is equated with increased discretionary time and household income. If the per capita GNP and fertility rates of the world’s countries are examined, a strong inverse relationship between the two can be readily identified. That is, total fertility rates (TFR = the average number of children that a woman can expect to give birth to) tend to decline as the affluence of society increases. This was the case for Australia during most of the twentieth century (table 3.3), the post–World War II period of increased fertility (i.e. the ‘baby boom’) 67being the primary exception. The overall trend of declining fertility is reflected in the size of the average Australian household, which declined from 4.5 persons in 1911 to 2.6 persons in 2006. It is expected to decline further to between 2.4 and 2.5 persons per household by 2031 (ABS 2012a).

One factor that accounts for this trend is the decline in infant mortality rates. As the vast majority of children in a Phase Four society will survive into adulthood, there is no practical need for couples to produce a large number of children to ensure that at least one or two will survive into adulthood to care for their aged parents and carry on the family name. Also critical is the entry of women into the workforce, the elimination of children as a significant source of labour and the desire of households to attain a high level of material wellbeing (which is more difficult when resources have to be allocated to the raising of children).

However, rather than culminating in a stable situation where couples basically replace themselves with two children, these and other factors have combined in many Phase Four countries to yield a total fertility rate well below the replacement level of 2.1 (it is slightly higher than 2.0 to take into account child mortality and adults who do not have children). While the resulting ‘baby bust’ may in the short term further enable adults to travel, the long-term effects on tourism if this pattern of low fertility persists are more uncertain. One consideration is a reduced tourist market as the population ages and eventually declines, if the natural population decrease is not compensated for by appropriate increases in immigration. Another is the shrinkage of the labour force, which could reduce the amount of pension income that can be used for discretionary purposes such as travel, while forcing longer working hours and a higher retirement age to avoid future pension liabilities.

TABLE 3.3 Australian demographic trends, 1901–2011

Source: ABS (1998, 2001, 2003, 2012), Lattimore & Pobke (2008)

68

Population increase

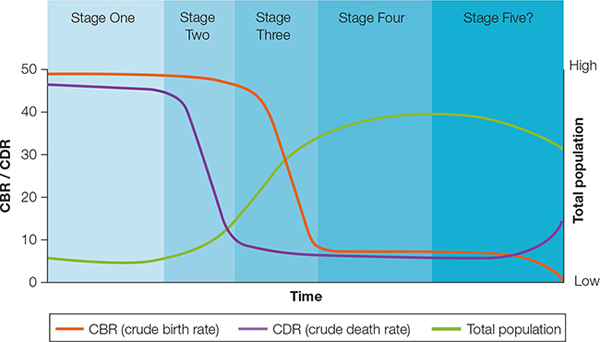

All things being equal, a larger population base equates with a larger overall incidence of tourism activity. Because of a process described by the demographic transition model (DTM) (see figure 3.5), Burton’s Phase Four societies tend to have relatively large and stable populations. During Stage One (which more or less corresponds to Burton’s Phase One), populations are maintained at a stable but low level over the long term due to the balance between high crude birth and death rates. In Stage Two (corresponding to Burton’s Phase Two), dramatic declines in mortality are brought about by the introduction of basic health care. However, couples continue to have large families for cultural reasons and for the contributions that offspring make to the household labour force. Rapid population growth is the usual consequence of the resulting gap between the birth and death rates.

As the population becomes more educated and urbanised, the labour advantage from large families is gradually lost and more resources have to be invested in children. Subsequently, the economic and social factors described in the previous subsections begin to take effect, resulting in a rapidly declining birth rate and a slowing in the rate of net population growth during Stage Three (roughly corresponding to Burton’s Phase Three). This is occurring currently in heavily populated countries such as India, Brazil, Indonesia and China and is accompanied by the stabilisation of mortality rates (and in China by an official ‘one child per couple’ policy for most families). The conventional demographic transition is completed by Stage Four (Burton’s Phase Four), wherein a balance between low birth rates and low death rates is attained.

The confounding factor not taken into account in the traditional demographic transition model, however, is the pattern of collapsing fertility and eventual population decline. If this persists and becomes more prevalent, it may indicate a new, fifth stage of the model (see figure 3.5). The experience of Australia does not yet indicate whether very low fertility is an aberration or not, since total fertility rates have been increasing since 2001 but remain below the replacement level of 2.1 (see table 3.3). In such a scenario, only sustained large-scale immigration is sufficient to sustain even a limited pattern of net population increase.

FIGURE 3.5 The demographic transition model

The demographic transition model basically describes the natural growth of the Australian population during the past 150 years, although the overall pattern of population increase was also critically influenced by high immigration levels as in the United States, Canada, New Zealand and western Europe. From a population of less than four million at the time of Federation, Australia’s population increased almost sixfold by 2011 (see table 3.3). Similar patterns have been experienced in all of the other Phase Four countries, culminating in the 850 million Phase Four consumers mentioned earlier.

Urbanisation

As happened in Ur and Rome, the concentration of population within large urban areas increases the desire and tendency to engage in certain types of escapist tourism. In part, this is because of urban congestion and crowding, but cities are also associated with higher levels of discretionary income and education, and lower family size. Australia differs from most other Phase Four countries in its exceptionally high level of urban population, and in its concentration within a small number of major metropolitan areas. By 2012, almost two-thirds of Australians lived in the five largest metropolitan areas (Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth and Adelaide). The ‘urban’ population in total peaked at about 85 per cent in the early 1970s and has remained at this level.

Increased life expectancy

Increased life expectancies have resulted from the technological advances of the industrial and post-industrial eras. In 1901, Australian men and women could expect a lifespan of just 55 and 59 years, respectively (see table 3.3). This meant that the average male worker survived for only approximately five years after retirement. By 2011 the respective life expectancies had increased to 79 and 84 years, indicating 15 to 20 years of survival after leaving the workforce. This higher life expectancy, combined with reduced working time means that the Phase Four Australian male born in 1988 can look forward to 298 000 hours of discretionary time during his life, compared with 153 000 hours for his Phase Two counterpart born in 1888 (ABS). However, favouring tourism even more is the provision of pension-based income, and improvements in health that allow older adults to pursue an unprecedented variety of leisure-time activities, assuming this pension income remains sufficient to accommodate such discretionary expenditure.

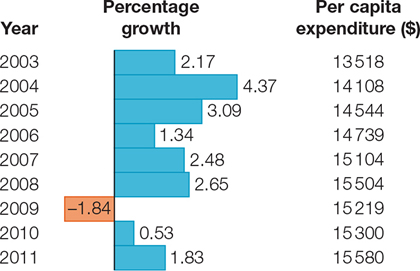

Because of increased life expectancies and falling total fertility rates, Australia’s population is steadily ageing, as revealed in the country’s 1960 and 2010 population pyramids (see figure 3.6). From just 4 per cent of the population in 1901, the 65 and older cohort accounted for almost 14 per cent in 2011 (see table 3.3). It is conceivable that within the next two decades Australia’s population profile will resemble that of present-day Germany or Scandinavia, where 18–20 per cent of the population is 65 or older. As suggested earlier, however, elevated levels of international in-migration could at least partially offset this ageing trend.

Contributing to this process is the ageing of the so-called Baby Boomers, those born during the aforementioned era of relatively high fertility that prevailed in the two decades following World War II. The baby boom can be identified in the population pyramid by the bulge in the 45- to 64-year-old age groups. The retirement of this influential cohort, which commenced around 2008, will have significant implications for Australia’s economy and social structure, as well as its tourism industry, 70particularly to the extent that the attitudes and behaviour of Boomers contrasts with emerging tourism consumers born after 1980 (see the case study at the end of this chapter).

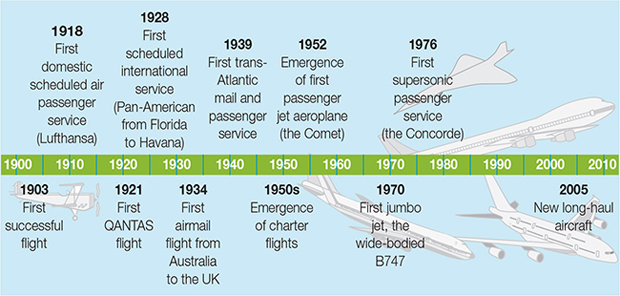

Transportation technology factors

The crucial role of transportation in the diffusion of tourism is demonstrated by the influence of the railway on the development of seaside resorts and by the steamship on incipient long-haul tourism during the late 1800s. However, these pale in comparison to the impact of aircraft and the car. figure 3.7 illustrates the evolution of the aviation industry. An interesting characteristic is the absence of milestone developments in aircraft technology between the 1976 debut of the Concorde (which has now been decommissioned) and the introduction of new long-haul aircraft such as the A380 and 787 Dreamliner in the early 2000s. Nevertheless, the world’s airline industry now accounts for more than 2.4 billion passengers per year (Goeldner & Ritchie 2012), and is a primary factor underlying the spatial diffusion of tourist destinations.

The development of the automotive industry has paralleled aviation in its rapid technical evolution and growth. The effect has been profound in both the domestic and international tourism sectors. Road transport (including buses, etc.) accounted for about 77 per cent of all international arrivals and an even higher portion of domestic travel by the mid-1990s (Burton 1995). Unable to compete against the dual impact of the aeroplane and the car, passenger trains and ships have been increasingly marginalised, in many cases functioning more as a nostalgic attraction than a mass passenger carrier. A notable Australian example of a ‘heritage’ railway-related attraction is Puffing Billy, a steam train from the early 1900s that transports tourists along a 24.5 kilometre route through the Dandenong Ranges of Victoria, which was originally built to facilitate the settlement of the area.

71FIGURE 3.7 Milestones in air travel

Political factors

Tourism is dependent on the freedom of people to travel both internationally and domestically (see Chapter 2). Often restricted for political and economic reasons in the earlier development stages, freedom of mobility is seldom an issue in Phase Four countries, where restrictions are usually limited to sensitive domestic military sites and certain prohibited countries (e.g. Cuba relative to the United States). The collapse of the Soviet Union and its socialist client states in the early 1990s has meant that an additional 400 million people now have greater freedom — and, increasingly, the discretionary income — to travel. More deliberate has been the Chinese government’s incremental moves to allow its 1.3 billion people increased access to foreign travel. Chinese leisure travel groups can only visit a foreign country that has successfully negotiated Approved Destination Status (ADS) with the Chinese government. In theory this assures that Chinese tourists receive a well-regulated, quality visitor experience. As of 2011, at least 140 countries (including Australia and New Zealand) were ADS-conferred (ChinaContact 2013). A critical factor influencing whether this high level of global mobility is maintained will be concerns over the movement of terrorists and illegal migrants.

AUSTRALIAN TOURISM PARTICIPATION

AUSTRALIAN TOURISM PARTICIPATION

The economic, social, demographic, technological and political factors described above have all contributed to increased tourism activity by residents of Phase Four countries in the post-World War II era. Australia is no exception, although trends since 2000 indicate both a dramatic growth in outbound travel (see table 3.4) and a concomitant stagnation in domestic overnight tourism trips (see table 3.5), a pattern largely attributable to the high relative value of the Australian dollar.

72

TABLE 3.5 Domestic overnight tourism trips in Australia, 2001 to 2011

Source: TRA (2012)

| Year | Number (000s) | Growth (%) |

| 2001 | 74585 | 1.1 |

| 2002 | 75339 | 1.0 |

| 2003 | 73621 | −2.3 |

| 2004 | 74301 | 0.9 |

| 2005 | 69924 | −5.9 |

| 2006 | 73564 | 5.2 |

| 2007 | 74464 | 1.2 |

| 2008 | 72009 | −3.3 |

| 2009 | 67670 | −6.0 |

| 2010 | 69297 | 2.4 |

| 2011 | 71895 | 3.7 |

FUTURE GROWTH PROSPECTS

FUTURE GROWTH PROSPECTS

Given the rapid change that is affecting all facets of contemporary life, any attempt to make medium- or long-term predictions about the tourism sector is very risky. It can be confidently predicted that technology will continue to revolutionise the tourism industry, pose new challenges to tourism managers and restructure tourism systems at all levels. However, the nature and timing of radical future innovations, or their implications, cannot be identified with any precision. In terms of demand, the number of persons living in Phase Four countries is likely to increase dramatically over the next 73two or three decades as a consequence of the condensed development sequence and the nature of the countries currently in Phases Two and Three. The former term refers to the fact that societies today are undergoing the transition towards full economic development (i.e. a Phase Four state) in a reduced amount of time compared to their counterparts in the past. The timeframe for the United Kingdom, for example, was about 200 years (roughly 1750–1950). Japan, however, was able to make the transition within about 80 years (1860–1940) while the timeframe for South Korea was only about 40 years (1950–90).

One reason for this acceleration is the ability of the transitional societies to use technologies introduced by countries at a higher state of development. Therefore, although England had the great advantage of access to the resources and markets of its colonies, it also had to invent the technology of industrialisation. Today, less developed countries such as India can facilitate their economic and social development through already available technologies. It is possible that China, in particular, with its extremely rapid pace of economic growth, will emerge as a Phase Four society by the year 2020. If this is achieved, then tourism managers will have to allow for 1 billion or more additions to the global market for international tourism. However, there are also the countervailing risks of a major economic depression, further spectacular acts of terrorism, health epidemics, cataclysmic natural disasters, and regional or global war involving nuclear, chemical or biological weapons. It will be the tourism systems with high resilience that will be best positioned to recover effectively from such disruptions.

74

CHAPTER REVIEW

Tourism is an ancient phenomenon that was evident in classical Egypt, China, Greece and Rome, as well as in the Middle Ages. Distinctive characteristics of tourism in this premodern stage include its limited accessibility, the importance of religious as well as educational and health motivations, and the lack of a well-defined tourism ‘industry’. Other features include the risky, uncomfortable and time-consuming nature of travel, its restriction to relatively few well-defined land and sea routes, and the limited, localised and unplanned spatial impact of tourism upon the landscape. Premodern tourism is similar to modern tourism in the essential role of discretionary time and income in facilitating travel, and the desire to escape congested urban conditions. Other commonalities include curiosity about the past and other cultures, the desire to avoid risk and the proclivity to purchase souvenirs and to leave behind graffiti as a reminder of one’s presence in a destination region.

The emergence of Europe from the Middle Ages marked the transition towards the early modern era of tourism, during which spas, seaside resorts and the Grand Tour were important elements. Concurrently, this marked the beginning of a period of tourism decline in China. The transition towards modern mass tourism was closely associated with the Industrial Revolution, and especially with Thomas Cook & Son’s application of its principles and innovations to the travel sector by way of the package tour and related innovations. Mass tourism emerged from the convergence of reduced travel costs and rising middle and working class wages.

The post-Cook era was characterised by the rapid expansion of domestic tourism within the newly industrialised countries. However, large-scale international tourism was delayed by primitive long-haul transportation technology, and by the appearance of two major economic recessions and two world wars between 1880 and 1945. It was not until the 1950s that international tourism began to display an exponential pattern of growth, stimulated by five interrelated ‘push’ factors that increased the demand for tourism in the economically developed Phase Three and Four countries. Economic growth provided more discretionary income and time for the masses. Concurrently, society perceived leisure time in a more positive way, moving towards a ‘work in order to play’ philosophy. Demographic changes such as population growth, urbanisation, smaller family size and rising life expectancies increased the propensity of the population to engage in tourism. Technological developments such as the aeroplane and car provided effective and relatively cheap means of transport, while overall political stability facilitated travel between countries. The experience of Australia is typical, with large-scale increases in outbound and domestic tourism in the post-World War II period. The global pattern of growth is likely to continue largely on the strength of a condensed development sequence that is rapidly propelling countries such as China and India into the ranks of the Phase Three and Four societies.

SUMMARY OF KEY TERMS

SUMMARY OF KEY TERMS

Baby Boomers people born during the post–World War II period of high TFRs (roughly 1946 to 1964), who constitute a noticeable bulge within the population pyramid of Australia and other Phase Four countries

BRICS countries Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, which account for 40 per cent of the world’s population and are expected to achieve Burton’s Phase Four status within two decades75

Condensed development sequence the process whereby societies undergo the transition to a Phase Four state within an increasingly reduced period of time

Crusades a series of campaigns to ‘liberate’ Jerusalem and the Holy Land from Muslim control. While not a form of tourism as such, the Crusades helped to re-open Europe to the outside world and spawn an incipient travel industry.

Dark Ages the period from about AD 500 to 1100, characterised by a serious deterioration in social, economic and political conditions within Europe

Demographic transition model (DTM) an idealised depiction of the process whereby societies evolve from a high fertility/high mortality structure to a low fertility/low mortality structure. This evolution usually parallels the development of a society from a Phase One to a Phase Four profile, as occurred during the Industrial Revolution. A fifth stage may now be emerging, characterised by extremely low birth rates and resultant net population loss.

Discretionary income the amount of income that remains after household necessities such as food, housing, clothing, education and transportation have been purchased

Discretionary time normally defined as time not spent at work, or in normal rest and bodily maintenance

Early modern tourism the transitional era between premodern tourism (about AD 1500) and modern mass tourism (since 1950)

Earned time a time management option in which an individual is no longer obligated to work once a particular quota is attained over a defined period of time (often monthly or annual)

Flexitime a time management option in which workers have some flexibility in distributing a required number of working hours (usually weekly) in a manner that suits the lifestyle and productivity of the individual worker

Generation Y also known as Gen Y or the Millennials; the population cohort following Generation X that was born between the early 1980s and early 2000s

Grand Tour a form of early modern tourism that involved a lengthy trip to the major cities of France and Italy by young adults of the leisure class, for purposes of education and culture

Industrial Revolution a process that occurred in England from the mid-1700s to the mid-1900s (and spread outwards to other countries), in which society was transformed from an agrarian to an industrial base, thereby spawning conditions that were conducive to the growth of tourism-related activity

Leisure class in premodern tourism, that small portion of the population that had sufficient discretionary time and income to engage in leisure pursuits such as tourism

Mesopotamia the region approximately occupied by present-day Iraq, where the earliest impulses of civilisation first emerged, presumably along with the first tourism activity

Middle Ages the period from about AD 1100 to the Renaissance (about AD 1500), characterised by an improvement in the social, economic and political situation, in comparison with the Dark Ages

Modern mass tourism (Contemporary tourism) the period from 1950 to the present day, characterised by the rapid expansion of international and domestic tourism

Olympic Games the most important of the ancient Greek art and athletics festivals, held every four years at Olympia. The ancient Olympic Games are one of the most important examples of premodern tourism.76

Package tour a pre-paid travel package that usually includes transportation, accommodation, food and other services

Pilgrimage generic term for travel undertaken for religious purpose. Pilgrimages have declined in importance during the modern era compared with recreational, business and social tourism.

‘Play in order to work’ philosophy an industrial-era ethic, which holds that leisure time and activities are necessary in order to make workers more productive, thereby reinforcing the work-focused nature of society

Post-Cook period the time from about 1880 to 1950, characterised by the rapid growth of domestic tourism within the wealthier countries, but less rapid expansion in international tourism

Premodern tourism describes the era of tourism activity from the beginning of civilisation to the end of the Middle Ages

Push factors economic, social, demographic, technological and political forces that stimulate a demand for tourism activity by ‘pushing’ consumers away from their usual place of residence

Renaissance the ‘rebirth’ of Europe following the Dark Ages, commencing in Italy during the mid-1400s and spreading to Germany and the ‘low countries’ by the early 1600s

Resorts facilities or urban areas that are specialised in the provision of recreational tourism opportunities

Seaside resorts a type of resort located on coastlines to take advantage of sea bathing for health and, later, recreational purposes; many of these were established during the Industrial Revolution for both the leisure and working classes

Social tourism tourism that enables socially disadvantaged groups such as the poor, young, old, unemployed and those with a physical or intellectual disability to participate in holiday travel as a basic human right

Spas a type of resort centred on the use of geothermal waters for health purposes

Stockpiler an employee who accumulates excessive leave time, thereby contributing to the financial liability of employers and underperformance of domestic tourism; estimated to account for about one-quarter of the Australian workforce

Thomas Cook the entrepreneur whose company Thomas Cook & Son applied the principles of the Industrial Revolution to the tourism sector through such innovations as the package tour

Tourism participation sequence according to Burton, the tendency for a society to participate in tourism increases through a set of four phases that relate to the concurrent process of increased economic development

Phase One (pre-industrial): mainly agricultural and subsistence-based economies where tourism participation is restricted to a small leisure class

Phase Two (industrialising): the generation of wealth increases and tends to spread to a wider segment of the population as a consequence of industrialisation and related processes such as urbanisation. This leads to increases in the demand for domestic tourism among the middle classes.

Phase Three (industrialised): the bulk of the population is urban and increasingly affluent, leading to the emergence of mass domestic travel, as well as extensive international tourism to nearby countries.

Phase Four (post-industrial): represents a technology- and information-oriented country with almost universal affluence, and a subsequent pattern of mass international tourism to an increasingly diverse array of short- and long-haul 77destinations. Almost all residents engage in a comprehensive variety of domestic tourism experiences.

Virtual reality (VR) the wide-field presentation of computer-generated, multisensory information that allows the user to experience a virtual world

‘Work in order to play’ philosophy a post-industrial ethic derived from ancient Greek philosophy that holds that leisure and leisure-time activities such as tourism are important in their own right and that we work to be able to afford to engage in leisure pursuits

QUESTIONS

QUESTIONS

Why is it useful to understand the major forms and types of tourism that occurred in the premodern era?

To what extent are virtual reality technologies likely to help or hinder participation in tourism to ancient sites such as Olympia?

What will be the likely environmental and economic impacts on such sites of this new participation?

Why is Thomas Cook referred to as the father of modern mass tourism?

Why did it take more than a century for Cook’s innovations to translate into a pattern of mass global tourism activity?

To what extent can destination managers extrapolate the global visitation and revenue data in table 3.1 to predict the future performance of their own specific country or city?

Is your household more or less time-stressed than it was ten years ago?

How has this affected the tourism activity of your household?

Do you believe that people have a basic human right to travel?

If so, how far should these rights extend?