CHAPTER 4

Controlling the Advisors

Although the ultimate responsibility for the success of a deal will rest with the board of directors and senior management, in most mergers there are a large number of advisors necessary to bring the deal to completion. Some of these advisors may be involved from the first step in the planning process through closing (and possibly even beyond), whereas other advisors will play a much more limited role during a very specific part of the merger process.

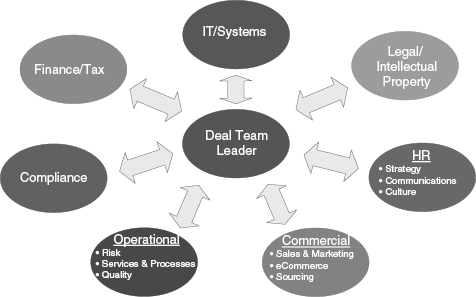

An example of the deal group from GE is shown in Figure 4.1. Some of these team members will be internal, others external, and for GE as with many firms, there will be a mix where, for example, the in-house legal team will be advised on the deal by external legal experts. Typically, the larger the company and the more frequently it engages in acquisitions, the more likely the existence of an internal team. Even in these cases, external advisors will be used when there are multiple deals simultaneously taking place or when a deal is outside the immediate area of experience or expertise of the team (say, in a new geographical area or product line).

Coordinating Advisor

Advisor roles overlap, but there are some general comments that can be made about each of the major types of advisor. The financial advisor is typically at the center and acts as the experienced coordinator of many of the other advisors and their activities. (Some experienced serial acquirers, such as GE, Siemens, or Cisco, will act as the coordinator.) The financial advisor naturally gives general financial advice but also drafts some and coordinates all documentation, often coordinates other advisors and often the client, advises on target valuation and deal pricing, manages the overall strategic direction of the offer, and lends its reputation to the transaction. There can be two financial advisors: an investment bank doing the M&A advisory work and a lending bank providing and coordinating the required funding for the purchase. The financial advisor will sometimes take on both roles as well as the additional job of stockbroker and link to the major investors in both the target and bidder if either or both are publicly held. The roles will differ depending which side of the deal the bank is advising, and both the bidder and target will have their own financial advisor. There can also be more than one financial advisor to each side, and in these cases the financial advisors must coordinate among themselves with one taking on the lead role.

External Advisor Roles

More specifically, when an investment bank represents the buyer, they will do some or all of the following:

- Find acquisition opportunities, such as locating an acquisition target or merger partner when the deal is not originated in-house.

- Evaluate the target from the bidder's strategic, financial, and other perspectives; value the target; provide “fair value” opinion.

- Develop an appropriate financing structure for the deal, covering offer price, expected final price including expenses of the deal, method of payment, and sources of finance (such as debt, equity, or cash); in some cases, they will provide the funding themselves or as part of a larger consortium of financing institutions.

- Advise the client on negotiating tactics and strategies for friendly/hostile bids or, in some cases, negotiating deals on behalf of the client.

- Collect information about potential rival bidders.

- Profile the target shareholders to “sell” the bid effectively; help the bidder with analyst presentations and “roadshows.”

- Gather feedback from the stock market about the attitudes of financial institutions to the bid and its terms (see also the stockbroker role below).

- Help to prepare the offer document (especially the “front end” (rationale)), profit forecast, circulars to shareholders, and press releases, and ensure their accuracy.

When representing a target, the activities of the financial advisor are different:

- Monitoring the target share price to track potential offers and provide an early warning to the target of a possible bid.

- Crafting effective bid defense strategies.

- Valuing the target and its divisions; providing a fair value opinion on the offer.

- Helping the target and its accountants prepare profit forecasts.

- Finding white knights or white squires to block hostile bids (discussed further in Chapter 6).

- Arranging buyers for any divestment or management buy-out of target assets as part of its defensive strategy.

- Negotiating with the bidder and its team.

Investment bankers need not sit in a pure investment bank and there are fewer of these than several years ago due to mergers and acquisitions among the M&A advisors themselves. Examples of this include the acquisition in 2008 of Merrill Lynch by Bank of America, a number of high profile bankruptcies including the famous demise of Lehman Brothers in the same year, and the transformation of two of the leading global M&A investment banks, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, into more traditionally regulated banks in the US soon thereafter. Investment bankers can work in one of the remaining pure investment banks (typically called “M&A boutiques”) that have recently been gaining market share in the industry or in another bank that has an investment banking division. The largest investment banking advisors are part of an elite group known as the “bulge bracket” firms. Although the membership of that group changes, typically the list of bulge bracket firms includes Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Citibank, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley, and UBS.

Solicitors and lawyers draft legal agreements and documents and also the “back end” (details) of the offer and defense documents. They give general corporate and regulatory advice and sometimes offer tax advice. They do the legal due diligence in identifying any potential legal and regulatory showstoppers to the deal. These might include antitrust investigation by the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) in the UK, the European Commission for the entire European Union, or the Federal Trade Commission in the US. The lawyers would prepare the bidder's case in such investigations.

The lawyers are particularly visible in hostile deals, as legal challenges to a takeover often form a critical aspect of a company's defense. Unlike investment bankers, their work often continues well past the deal closing date when the two companies formally combine. Their involvement in post-deal integration can be extensive, with new employment contracts, supplier and customer contracts, and other issues remaining to be resolved.

Most of the leading law firms today would defy characterization as being regional or from a single country or city, but the largest law firms have traditionally been known in London as the “Magic Circle” (Allen & Overy, Clifford Chance, Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, Linklaters, and Slaughter and May); the similar group of US-headquartered law firms includes Cleary Gottlieb, Cravath Swaine, Simpson Thacher, Skadden Arps, Sullivan & Cromwell, and Wachtell Lipton. Law firms that are not large enough to have offices around the world will often have relationships with local law firms in the locations where they do not operate directly themselves.

Another role of the lawyers is to deal with the lawsuits which invariably arise following a deal. Cornerstone Research released a report in 2012 which found that 96% of all US deals worth over $500 million were challenged in court the previous year (up from 72% in 2008 and just 53% in 2007), although their report did find that 67% were settled quickly.

Accountants draft the “middle bit” (numbers) of the offer documentation and provide the “independent” financial information as required (typically three years); note that it is management, not the accountants, that produces the financial forecasts. Accountants will give tax advice (when lawyers don't) and often take on the bulk of due diligence. Many accountancy firms have specialist consultancy divisions as well that may be involved in specific areas such as compensation and benefits and other HR issues. The accounting firms will also provide many of the services noted above in the section on investment banks, to middle-market clients who are too small to be served by the large investment banks, other than the provision of financing and the roles of a stockbroker.

Globally, the largest accounting firms are known as “The Big Four,” which is composed of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu (commonly referred to as “Deloitte”), EY, KPMG, and PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). Interestingly, the concentration of power in these four firms was the result of mergers that have taken place since the 1980s between what were then known as “The Big Eight,” but they have as well combined with a number of other national firms. These large accounting firms therefore not only have advisory experience, but also first-hand internal knowledge about what transpires in a merger and the challenges to integration.

HR consultancies have an increasingly important role in supporting the two parties in the bid. From a bidder's perspective, it is critical to know the strength of the target's senior and even middle management teams. The bidder needs to know as well whether those people will stay with the new company and what incentives will be required. There may be other personnel-related issues as well, such as redundancy requirements, union contracts, pension deficits, and many cultural issues to consider. Likewise, the target has an interest in knowing how it will be treated in the new organization. These HR consulting firms should also be heavily involved in the post-deal integration period, as will be discussed in Chapter 10.

As shown in a survey from 2010 conducted by Towers Watson, one of the largest HR consulting firms in M&A, the four top priorities for HR in a company which is acquiring are: to communicate effectively and openly with employees, create and implement strategies to retain key staff, focus on cultural alignment, and provide due diligence support. The same survey showed that HR as a department is seen as being more effective (by more than double in some areas) in successful deals than those which were less successful.

Stockbrokers, when separate from investment bankers, are the eyes and ears in the market for both the bidder and target. They are the principal line of communication with institutional shareholders and, because of their knowledge of the markets and the investors, they provide input on valuation and pricing. They may also organize other banks and brokers, should it be necessary, in raising additional funds. They may sometimes liaise with regulatory authorities on the strict requirements of regulatory filings. An investment bank may also act as a stockbroker, as noted earlier.

Public relations advisors help with the selling message to multiple audiences, including not just the shareholders who will ultimately determine whether the deal is acceptable, but also to the management and staff of both companies, customers, suppliers, and the general public. They may organize various campaigns through press briefings, one-on-one or group presentations, and other media events. Note the role of PR advisors in the DP World case study in the previous chapter as they were, albeit unsuccessfully, trying to sell the purchase of P&O to the public, including the hiring of lobbyists to discuss the deal with the politicians on Capitol Hill. As we mentioned earlier, this type of activity is an integral element of the intelligence function.

There are numerous other advisors as well, including:

- Consultants of all types advising on topics such as strategy, due diligence (including firms which run electronic virtual due diligence rooms), governance, post-deal integration, security issues, and virtually any aspect of the deal. These specialist consultants can also form “clean teams” to assist with early negotiations (discussed later in Chapter 9).

- Registrars who control shareholder lists and organize communications with shareholders and share transfers on both sides.

- Receiving banks that will take in offer acceptances and ultimately pay out the consideration to the target shareholders.

- Printers for the myriad documents required.

Some of the advisors related to business intelligence gathering will be discussed in greater detail in later chapters, as will corporate intelligence consultants in Chapter 7 on due diligence.

Corporate Development

In many of the larger companies, there is a permanent group that typically goes by the name of “corporate development,” although variations on that term exist. This is an internal group with responsibility for conducting M&A deals for their own company (what can therefore be called “proprietary M&A,” distinct from the external advisory M&A roles noted earlier in this chapter).

There is no “one size fits all” model for a corporate development group: sometimes it reports directly to the CEO, or it might be part of the Chief Financial Officer's function, or a strategy group reporting to the Chief Operating Officer. What is common, however, is that the group operates at a high level within the organization. In particularly large companies, there may even be corporate development departments within some of the major divisions.

These corporate development departments are usually unable to do all of the activities of an M&A deal by themselves except for very small deals, so they work closely with the external advisors, bringing them in for specialized expertise when required. This includes the intelligence specialists who should be central to the corporate development function but who too often are perceived as a peripheral resource.

In a study conducted by KPMG in 2004, it was found that corporate development departments that quantify and measure projected synergies at the initial phase of a deal stand a greater chance of success than those with a more disjointed approach. They maximize business unit involvement and set integration milestones. The study also found that these milestones are more likely to be met where the corporate development department monitors the integration process.

Advisor Selection

The selection of advisors is itself a strategic decision. Certain advisors have the reputation and experience which makes them the first choice in an industry. Others will be the leading specialists in particular aspects of a deal – for example, Goldman Sachs, one of the largest M&A investment banks, is particularly well known for its defense of targets in hostile bid situations. If a bidder therefore knows – as it will! – that it will be launching a hostile bid, then it might be advantageous for that bidder to engage Goldman Sachs as its advisor. In this way, it will force the target to choose an investment bank that may not have as much experience. This assumes, of course, that the advisor is not already on a retainer or has recently represented the target, as it would then be conflicted in the deal and recuse itself from representing the bidder (see the case study of M&S in the box below). It should also be obvious that the bidder is at an advantage in choosing its advisors; targets in unsolicited or hostile bids will typically be responding to the unexpected with more severe time pressure and limited choice as the bidder will have set the stage.

There can be multiple advisors providing advice to each side of an M&A deal, especially in a large deal. As reported by the Financial Times in August 2013, “in recent years, the average number of financial advisers on $10 billion-plus deals has totaled about five. At extremes, the numbers are far higher, especially when complex or risky financing packages are required.”

In the highly leveraged bid by Michael Dell that year to buy back the company he founded (Dell Inc.), there were 11 financial advisors. Another deal in 2013, the $10 billion acquisition of the stock exchange company NYSE Euronext by Intercontinental Exchange, had 13 financial advisors in total, which is the same number as those who worked on the deal that resulted in the Royal Bank of Scotland Group, Fortis, and Banco Santander acquiring ABN AMRO Bank for €71 billion in 2008.

How Advisors Are Paid

How advisors are paid is an important factor in understanding how they operate. When representing buyers, financial advisors typically charge a retainer, management fee, and abort fee in addition to (in the case a deal is successful) the much larger and more substantial portion of their fee that is determined as a straight percentage of deal size/consideration (albeit a percentage which is inversely proportional to the deal size). Because of this fee structure, the investment bank shares the risk involved with the acquisition process given that the success of the deal can often influence not just their reputation (which applies to the other advisors), but also their fees. “Success” for this fee is defined as the deal completing – reaching closing when the two companies formally combine. Sometimes the fee can be time-based for a limited number of months, which is then set off against the success fee if the deal does complete.

Because the success fee is larger if the purchase price is higher, some observers claim that there is a motivation for the buyer's investment bank to seek a higher price for the target – a result that would clearly not be in the best interests of the buyer. Therefore, periodically there are arguments made for changing the fee structure to have larger retainers, which would then later be set off against the ultimate – but smaller than traditional – success fee. However, in talking to clients, most tell us that their goals are already aligned with the advisor because the best outcome for both will be a deal that can complete, as noted above. Thus, these clients not only say that they prefer the traditional success fee payment structure but that they believe such a structure will remain unchanged in the market.

These financial advisors are typically not involved in the deal after closing, unless their firm (usually a different division) has provided financing, in which case they are focused at that point on making sure that the company is efficiently run with enough cash to pay the interest and ultimately the principal on any debt used to finance it. This financing may also have been syndicated to a number of other banks as well, in order to limit the risk for any one issuer.

Financial advisors representing the target have found it more difficult to structure a “success fee,” and thus the fees in these instances tend to be time-based or as a fixed percentage of deal size. These fees, according to consultants Freeman & Co. as reported in Financial News, are approximately 2–3% of deal value for deals up to about $100 million, but above that will decline as a percentage of a deal to between 1% and 1.5% for deals up to $1 billion, and even lower for megadeals larger than that. According to one study by Bloomberg, the fees ranged from 0.32% in the largest deal reported ($4.5 billion) to 3.06% in the smallest ($70 million). The advisors to the buyer will typically get 60% to 90% of their fees based on success of the deal. These success fees are more difficult to structure because of the potential conflicts of interest. In some jurisdictions, such as the US and the UK, the overall level of fees must be disclosed.

There may also be fairness opinions which look principally at the valuation only; for these, fees from either the buyer or seller – or both – will range between $50 000 and $300 000. In some deals, the independent directors of the company will request this fairness opinion as a check on the principal advisor's recommendations.

Banks can also earn substantial fees from lending funds to the buyer or arranging other financing, such as an equity offering or a debt issue. Some of the fees for this financing are due even if the deal does not complete. For example, BHP Billiton paid $250 million in 2010 to the banks who arranged the $45 billion acquisition financing for their aborted takeover of Potash Corporation, even though that deal was ultimately blocked by the Canadian regulators for competition reasons. Total fees paid by BHP Billiton in that deal were $350 million, according to their press release after the deal was terminated.

Accountants and lawyers are also typically time-based and often will agree to a cap (with “get-out” clauses in case the deal develops along lines very differently than anticipated).

Despite their expense, our research has shown that the inclusion of a financial advisor is good for buyers because the advisors increase shareholder wealth by finding bidders or targets with greater value, providing advice on premiums, identifying liability concerns (including demonstrating to shareholders that they did the most they could to achieve the best deal for them), providing local knowledge in increasingly complex cross-border deals, and, because of their competence, increase the probability of a deal's successful completion.

This was confirmed in a ground-breaking research paper published in the Journal of Finance in February 2012, in which Andrey Golubov et al. provided further evidence on the role of financial advisors in M&A deals. They found that deals advised by top-tier, so-called bulge-bracket, investment banks delivered higher bidder returns than their non-top-tier counterparts but in public acquisitions only, where the advisors' reputational exposure and required skillset are relatively larger. This translated into a shareholder gain of over $65 million for the average bidder. The authors attribute this improvement to top-tier advisors' ability to identify more synergistic combinations and to get a larger share of synergies to accrue to bidders. Not surprisingly, top-tier advisors did charge premium fees in these transactions as well.

In comparison to the financial advisors, the legal, accounting, and other advisors share less of the risk of deals with their clients as their fees are not as dependent on the success of the transaction completing, although, as with investment banks, their reputation is.

Advisors and Business Intelligence

Each of the advisors can play an important intelligence role, although often each advisor's actual role is limited to their traditional functions. Accountants check and produce the numbers but, if asked, can provide important information about the industry and other companies in the market. Investment banks may drive the overall process and be responsible for the valuation, pricing, and negotiation, but are also important reservoirs of information about the market and competitors. They have Chinese walls that operate to keep information from one deal being used on another, but the general experience of the senior investment bankers themselves is often enough to provide a client with information that otherwise could not be obtained. As Giuseppe Monarchi, Managing Director of Investment Banking and M&A Europe at Credit Suisse, told us, “ ‘Having been there before’ is of tremendous help; although every situation is different from another, I find it striking how much things tend to repeat themselves and especially people's behaviors. Having been there before gives you the confidence to take difficult decisions.”

Both large, global consultants and small boutique advisors are renowned for their ability to seek out non-public information about clients and customers. There is a demonstrated willingness of employees, suppliers, and clients to provide information for no other reason than having been asked. Often it is difficult for a company to ask this information directly because they would need to identify who is asking. Consultants, on the other hand, do not need to disclose their clients unless asked – and frequently are just not asked! Why people are so willing to divulge confidential information to experts is not always clear, but what is clear is that many will do so for no other reason than that someone has asked them.

Some specialist consultants focus specifically on due diligence work and intelligence gathering. One or several steps up from the detectives made popular by Hollywood, these consultants can be masters at finding information that is otherwise difficult to obtain. Although there are those that operate on the wrong side of generally acceptable ethical and moral principles (granting that these may differ by culture, country, and individual), there is also much that can be done for targets or bidders by these investigative firms on the totally right side of the law. Selection of such consultants is therefore a key factor in successfully obtaining the information required.

Conclusion

Once a deal is announced and even if there are only rumors of a deal, advisors from all professions will descend upon the two companies. Each will have a unique and often compelling marketing pitch describing how the deal will proceed better (read: cheaper, faster, more efficiently, with less distraction to the core business, with greater long-term performance, with fewer redundancies, and so on). This is why there is one intelligence omission that you may have noticed. Do not forget to employ (internally or outsourced) your intelligence function on your advisors. No matter how reputable the advisors or how much work in the deal is conducted by the external consultants, the board, senior managers, and employees are the ones who will live with the result for years. This responsibility cannot be delegated.