CHAPTER 3

Designing the Acquisition Process

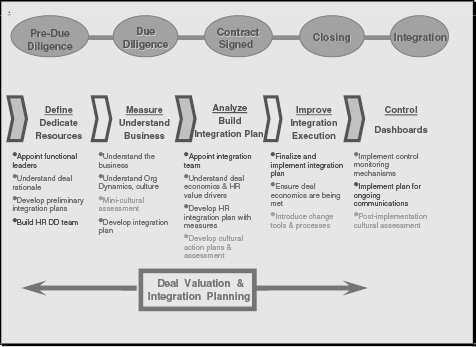

All stages in the takeover deal process require the effective use of business intelligence. Some points in the process (such as due diligence) will appear to fit more naturally into the traditional view of business intelligence, but effective use of the techniques outlined will assist in improving the success rate at all stages of a deal from when a takeover is first proposed through to the continuing integration of the two companies years after the deal has been consummated.

The term “appear to” is used above because even traditional due diligence has often been unfocused and therefore unsuccessful. This was certainly true in the case shown in Chapter 1 when Quaker Oats did not find out about the drop in sales of its target company (Snapple) until several days before the deal was announced, despite the ability to check with suppliers, grocery stores, and industry analysts about the sales of Snapple's drinks. Quaker Oats did not need to rely on Snapple to get this information and, even if they had received that information in a timely fashion directly from Snapple, they should have verified it with other external sources. As shown in that case, Quaker Oats could also have conducted better due diligence on the differing distribution systems used by its own Gatorade division and the target, Snapple. Similarly, in Chapter 2 we showed the spectacular intelligence failures of the Royal Bank of Scotland in their purchase of ABN AMRO.

Steps in a Deal

Although each acquisition or merger deal is unique, in general the merger process usually involves the steps shown in the box below. The buyer's perspective differs from the seller's, but both largely need to follow these steps. Steps overlap and in some deals there will be a loop back to an earlier stage. Some steps will be brief in certain deals. These include the strategy planning stage, which may be shortened dramatically if a bid is made in immediate reaction to a bid for the same company by a competitor; this doesn't obviate the need to make sure the strategic rationale is fully developed, it just means that it has to be done in a much shorter time period, including appropriate reviews. Conversely, other steps in the process, which may have appeared unimportant, will gain much greater importance. For example, if something totally unanticipated is uncovered in the due diligence process, it may require a change in the price or other terms. Anticipating the likely stages and timing will assist greatly in planning the deal. In certain situations (such as unexpected hostile bids), some of the steps may be shifted or even ignored due to time constraints.

Although it is more common for buyers to initiate a deal, targets can also put themselves up for sale. Sellers initiate deals most commonly when they are experiencing some difficulty: financial difficulties including anticipated growth needs that cannot be funded through earnings, succession issues (especially with private companies where there has been a strong founder or start-up entrepreneur), or even legal issues (where the company has been the target of a major lawsuit, for example). They will have determined a price range, perhaps working with their advisors, if any, although there are many cases where the sale price expectation is not at all reasonable. It is critical to determine the underlying reasons because they are not always stated. The stated reason may in fact be a minor factor, with the real driver left unspoken. Understanding these reasons is an important business intelligence responsibility.

Targets may not even know that they are being sold. Investment bankers and other advisors keep lists of companies that are possible targets and then take those lists to companies that may be interested in growth through acquisition (or may only be interested in making sure that a competitor doesn't get their hands on the target).

Selling Approaches

Once a seller has done the strategic review to determine whether to put itself or a division up for sale and has engaged the appropriate advisors to support the sale, including intelligence specialists, there are three major approaches to selling with each having unique advantages and disadvantages:

- Public or open auctions are preferred when there are “trophy” assets that are likely to be attractive to a large number of potential buyers and where confidentiality issues are unlikely. The advantages include an ability to show to shareholders that the best price has been achieved for the company/division as the largest possible market of potential buyers has been targeted. However, such auctions can be very embarrassing for management and the company (with impacts on reputation, sales, and employee morale), especially if the auction fails to find a buyer at an appropriate price. There is also the risk of competitors seeing information that is better kept confidential. These public auctions are also difficult to control and sometimes develop a life of their own. Nevertheless, public auctions are often required for assets that governments privatize, such as the sales of state-owned telecommunications companies, power companies, airports, postal services (as with the Royal Mail in the UK in 2013), and even roads.

- Limited private auctions approach a limited number of parties and are useful where there are a small number of relatively easily identifiable potential buyers. This is a preferred route of the major investment banks. The advantages in these limited private auctions are that they usually maintain a good level of confidentiality and less public and internal embarrassment if the auction fails. Nevertheless, there is a high level of skill required to build the “feeding frenzy” required to get the highest price, although an experienced advisor should be able to generate this interest and avoid the risk of a limited private auction too quickly becoming a bilateral discussion if that isn't what is desired.

- Bilateral discussions are useful where highly confidential issues exist (such as client lists or intellectual property representing a large portion of the target company's value), where there are only a limited number of potential purchasers, or when speed is required, perhaps in the situation of a company in distress in which value is eroding quickly. If this process (also called a “negotiated sale”) is followed, it may involve contacting one buyer at a time in order of anticipated interest and ability to meet the expected sale price. Such discussions by their nature have a reduced effect on customers, employees, and suppliers, but are rarely the best way to achieve the highest price for the company or division being sold. It may therefore be very difficult to justify such bilateral discussions to the owners or shareholders of a company.

Assuming an open auction or limited private auction, a “long list” of companies to participate in the auction or discussions needs to be identified. Such a “long list” may even be developed for bilateral discussions although only a small number will actually be contacted. The advisors will usually look both vertically and horizontally in the industry, consider whether management may want to buy the company or division, whether there are financial buyers (such as hedge funds or private equity firms), and visit companies that may have expressed an interest in the past or recently attempted and failed in another purchase. The use of intelligence techniques to develop this list will be discussed later as it is important that potential bidders not be missed, nor is it useful to waste time on those who would not make it through the process. Indeed, the M&S example has some ironic echoes. As discussed in the previous chapter, for years, M&S operated in an externally ignorant cocoon.

The long list of companies is then prioritized and those most likely to bid are given confidentiality agreements before continuing the discussion. At that point, an information memorandum developed in the preparation phase is distributed to the interested companies and their advisors. Some potential bidders will be uninterested and drop out. The timing can vary widely from start to finish in this step, but will typically take four to six weeks from the time that the “long list” companies are contacted.

Then the deal moves into the “short list” stage where each short-listed company is given further information. Four to seven bidders are ideal in this stage. Four to six weeks for this stage is again common, assuming that there is no regulatory need to do the deal more quickly because of public announcements. Another reason that the deal may progress faster at this and the prior stage is if the target company is in distress or has already entered into bankruptcy proceedings prior to the process beginning or indeed during it. If in bancruptcy, it is likely that an administrator has been appointed (frequently one of the major accounting firms) who is tasked to conduct a sale process that maximizes the price received, which usually means that speed is of the essence.

Tactics are important and the need for good intelligence on the bidders is critical: for example, does each buyer get the information that it specifically requested or do they get all the information in aggregate? This dissemination of information is often done in a document or data room (whether physical or virtual, which will be discussed in Chapter 7), and again there are tactical decisions to be made as to where the room is located, how access is gained, how often potential bidders can gain access, whether some or all of the information is online, and which advisors can participate. Other due diligence efforts will take place as well, including meetings with management, visiting sales offices and manufacturing plants, talking to clients, interviewing financial staff, and so on. Through all of this, the companies that didn't make the short list must be kept informed in case any or all of the short-listed companies drop out of the bidding.

Lastly, there is the selection of the winner – the “preferred bidder.” From this point, that bidder will get exclusivity to further proprietary information in order to conduct further due diligence. The parties will negotiate a “letter of intent” with the expectation that the process will move quickly to the point where a “sale and purchase agreement” is signed and exchanged. One or more of the “losers” may need to be kept warm in case the preferred bidder declines to make a final offer or if there are problems in closing the deal with that buyer. Here again, constant intelligence monitoring is often neglected. The complacent period surrounding perceived victory is very dangerous, as we will see later in this chapter in the case of Dubai Ports. Ultimately, the final contract is agreed and signed. Certain conditions may have been entered into the agreement, such as regulatory issues, the ability to arrange the necessary financing, and final shareholder approvals (often in a special general meeting of shareholders). Once again, speed is necessary. Simultaneously, proper attention needs to be paid to the due diligence process of determining whether the buyer is truly buying what is expected. This can be fast: early in 2013, Liberty Global, the multinational telecommunications company, bought Virgin Media for $23.3 billion in a deal which took just three weeks to complete, according to the Financial Times. We will return again to Liberty Global in Chapter 9 when discussing competition authorities.

Timing

Although the timing can range from days (in the case of some private companies) to several years (most notably when there are regulatory matters involved and multiple jurisdictions), an “average” deal without such regulatory matters can be completed in three to four months from the time that the deal is announced. Prior to that public announcement, the various stages can vary widely in duration, but generally speaking the preparation for sale of a company would take four to six weeks, the marketing another four weeks (although longer if an auction and shorter if the deal is one where the company is already insolvent or in danger of being so), the buyer selection approximately four weeks if there are no significant complications, and then the final negotiation (leading to the announcement) a further three to four weeks.

There is no set duration for the period a buyer takes in determining its acquisition strategy, including the organization of the internal and external team members. Some companies have corporate development departments that continually scour the market for potential acquisitions and advisors tasked to do the same (and to be “on call” in case a deal becomes active). These companies can respond quickly to an opportunistic bid or an unsolicited takeover attempt.

Assuming no external pressures, these steps should not be rushed. The proper amount of time to be allotted to the complex process of an M&A deal needs to include an appropriate period for conducting adequate due diligence and then the resulting analyses. The larger and more complex the deal – and the larger the deal team – the longer the time required. Acquisitions of private companies also can take longer as less information is in readily available format in advance, but as noted earlier with the Liberty Global/Virgin Media deal, when there is a need for speed, the deal can be completed much more quickly.

Regulation can represent one of the most likely reasons for a deal to be delayed, although proper intelligence gathering and analysis should highlight when this is likely to take place. According to one study by the consultants McKinsey, approximately 40% of all US deals involved detailed requests from regulators for information and almost 4% ultimately had a legal challenge, thus delaying the closing considerably beyond the initial target date. Regulatory approvals may have influenced the findings of a 2013 study by DLA Piper that found that 40% of all deals did not close within nine months of announcement.

Managing the Process

This merger process can and should be managed from both the buyers' and sellers' sides and, ideally, coordinated between them. Unfortunately, all too often the process itself becomes the manager, especially when there is an inability to decouple from the deal once it is under way. These so-called “runaway deals” occur when the momentum of the deal takes charge and when executives and advisors get embroiled and lose objectivity. As Booz & Co stated in an article from Strategy + Business in November 2011, the top M&A fallacy is “We can't walk away from this deal.”

The following issues should be considered to avoid this problem:

- It is important to remember that the deal can change during the process.

- In the early stages, there is only limited knowledge of the target, so be willing to change opinions.

- Some employees, especially on the buyer's side, will “go native” on the deal and lose objectivity, falling prey to “confirmation bias” whereby they discount information that would scupper the deal and only pay attention to data which confirms their goal of completing the deal.

- The process should allow for withdrawing from the deal at any stage; to make this easier and more acceptable, review and exit points should be explicitly designed into it so that all parties understand that this might take place.

- Public and external pressures will interfere with the internal process, often to the detriment of the two combining companies; these external pressures may also distract from the more important internal priorities. Nevertheless, it is folly to think that management can ignore this, and there are many deals that have been terminated because of external political and public opinion pressures, as shown in the case study below about the purchase by Dubai Ports World of P&O.

- There is a tendency to postpone ambiguities until after the deal has closed, but this is dangerous. Any uncertainty about significant items or insufficient information should be resolved before the deal closes (and optimally much before that).

- Employees and managers will be distracted first by the “me” issues of whether they have a job or not in the post-deal company. These “me” issues must be rapidly addressed as soon as the deal is communicated.

The deal itself creates potential, but this must be managed in order to realize it. Value is created only in post-deal integration, although it clearly depends on strategy and price as well.

Nevertheless, there can be a tendency in companies to spend too much senior management attention on the deal, ignoring the ongoing business. This must be avoided. In the words of Michel Driessen, Senior Partner, Corporate Finance at EY, “In our experience, the success of a transaction is linked directly to management having adequate resources to ensure the focus on [the] day-to-day activities of their business is not compromised.” We will come back to this advice later when we look at the post-deal integration.

Yet with all the best planning and advisors, no deal will ever proceed exactly as planned. Perception may be more important than reality. As President Dwight Eisenhower said of his time leading the Allied forces in Europe in World War II, “In preparing for battle I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.” Among other reasons, he must have known that the very act of planning would enable him to react more swiftly once the battle situation shifted.

The intelligence function used effectively is a tool which can guide the team to gain the most from perceptions about the roles and abilities in the takeover battle of the company, its advisors, and the competition. If used correctly, it helps to maintain a clear understanding of the principal current perceptions surrounding the prospective deal and, since the role of intelligence is an iterative process, it ensures that the changing moods and dynamics of these perceptions are incorporated into the planning and deal process.

Questions needing answering include determining which perceptions are the most widespread, which are the most powerful, which are likely to be developing, and which are losing favor. Crucially, intelligence allows the team to understand its own position and how others perceive them and vice versa. Also, along with the motivations for advisors driven by their billing models (whether fixed fee, time-based, or as a percentage of the deal size), their perceptions need to be monitored.

The process is dynamic. There needs to be constant monitoring of the changes in the environment; that then enables a company to take advantage of certain perceptions, limit the damage of others, and even to ensure that perceptions are moving in a direction that will provide benefits when it is possible to influence them. This clearly was not done in the Dubai Ports case study above, despite an attempt to anticipate some of the issues prior to the deal announcement. However, in order for this to be done successfully, the most important factors at play must be understood.

One executive in a major global investment bank described how important it is to gauge shareholder attitudes in cases where the management is accountable for their decisions to the shareholders: “Always make sure you know who gets to make the decision: what are their attitudes and perceptions surrounding the issue? That way you can make sure to play the right card in the right way and at the right time.” He further highlighted that the decision making process usually goes through various levels and, as such, actions need to be targeted according to the perceptions at each stage of the decision making ladder.

Lastly he described how those who make the final decision are often made up of certain groups, so, for example, when dealing with shareholders, corporate shareholders will hold very different opinions and perceptions than private individuals. Depending on the size and overall stake, a different approach will need to be targeted at the important groups. Thus whatever the context, the groups that hold varying degrees of power always need to be identified, understood, and managed accordingly. As shareholders, these are the people who will ultimately determine the fate of a deal at that phase of the takeover process.

The example in the box clearly illustrates the need to identify who has control or influence over the key decisions at all levels. Perhaps if the bank in the example had realized in advance what the perceptions of their rating agency were, they could have reassured both the market and the agency, and carried out some further actions to prove their commitment. In this way they might have been able to retain the profitable acquisition and their Eastern European expansion plans, rather than rushing out under the panicked enforcement of their rating agency about the acquisition, which resulted in immediate losses and left them missing out on a major growth opportunity. Another example where a stakeholder perception was ignored or where the intelligence function failed was Deutsche Bank in its acquisition of Bankers Trust in 1999: that deal was delayed by several months and almost prevented completely by the surprise (at least to Deutsche Bank and its advisors) insistence of the New York State regulators that the issue of payments to Holocaust victims by the German government be resolved before approval would be given for the acquisition. The box below describes another deal, this time scuppered by the unions.

Throughout the deal process, effective communication will be necessary with all the affected and interested parties. This is particularly important in the post-deal integration period, as will be discussed in Chapter 10. But it is no less important at other points in the deal process. For example, a Cass Business School study, released in 2014, found that the announcement of a deal can be significantly impacted by factors such as whether the offer is proactively put forward by the acquirer or made as a reactive response to press speculation. The former leads to a deal completion rate of 84% as opposed to only 50% for deal announcements in response to the press.

The content of the announcement can also have an impact on the deal, as can the inclusion of information about the new leadership team and an explicit timeframe for cost savings. That same study found that when a strategic rationale was explicitly discussed in the deal announcement press release, the later performance of the combined companies was better than in deals where the announcement did not discuss strategy. Other studies have identified other factors important in these communications, such as what time during the trading day the deal is announced: companies prefer to release such announcements, especially if the target or buyer is public, either before the market opens or after it closes. This gives shareholders more time to evaluate the impact of the disclosure and avoids the possibility that trading in the shares might have to be halted.

There is also a tendency for deals to be announced on a Monday, leading to a situation referred to as ‘Merger Monday’ when a large number of deals are announced on the same day. Why Monday? Because this gives the negotiators the weekend to complete the details, working round the clock. This was especially important when print media dominated, but remains so even in an era of deal announcements on social media. For example, 2014's first ‘Merger Monday’ occurred on only the second Monday in the year, on a day when Time Warner Cable rejected a $61 billion offer from Charter Communications; other deals on that day included Google's announcement of their $3.2 billion purchase of Nest Labs, a four-year-old start-up founded by Apple veterans that makes “smart” thermostats and smoke alarms for the home.

LBOs/MBOs

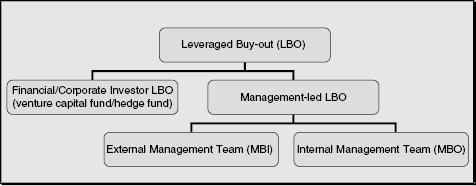

Certain types of deal will bring with them particular problems. This is certainly true for management buy-outs (MBOs) and related structures (such as management buy-ins – MBIs). These are a subset of leveraged buy-outs (LBOs) which utilize a high level of debt to buy the target company. This structure distinguishes them from the most common type of merger or acquisition transaction where one company acquires another company, or two (or more) companies decide to merge into one, usually in exchange for stock or cash. As with the overall M&A market, the level of LBOs is cyclical, having historically been a larger percentage of the overall market when debt is cheaper and easier to obtain.

The perception that there is a significant potential for conflicts of interest in management buy-outs is due to the fact that managers in public companies are fiduciaries for stockholders, charged with the responsibility for maximizing the price shareholders get from selling the company or division, but in the case of an MBO, they are also the buyer and therefore have an incentive to minimize the purchase price. An example of this was the relatively low offer in the form of an MBI by a management group led by Ross Johnson (an inside manager) in the RJR Nabisco LBO deal in the late 1980s which was then quickly surpassed by KKR, who ultimately purchased RJR Nabisco in the largest LBO of that decade. This issue was paralleled to a degree in 2013 with the attempted purchase for $24 billion by Michael Dell (together with partner Silver Lake Management) of the computer company that he had founded with only $1000 of seed money in 1984. Other shareholders, notably led by activist investor Carl Icahn, fought his bid as undervaluing the company.

Directors are prohibited from favoring a management bid over another bid, which was certainly an issue in the Dell case above. To avoid charges of insider trading in an MBO, management must disclose all material and non-public information or refrain from trading in the stock of the company. Full disclosure by management is an effective defense against such allegations.

In an MBO, an internal management team arranges the leveraged purchase of the company, but with an MBI it is a group of managers from outside the company that arranges it. The different types of LBO can be as shown graphically in Figure 3.2.

In any type of LBO, the cash is borrowed using the target's assets and expected cash flows. Debt is therefore secured with the assets of the enterprise being acquired. This is why the financing is often referred to as “asset-based lending.” Therefore many LBOs are in capital-intensive industries that have assets that can be used as collateral for debt; they don't take place as often in service industries where there are fewer fixed assets.

Although the LBO deals that gain the most attention in the press often involve an entire company being taken private in leveraged financing, some LBOs involve the purchase of a division of a firm rather than the whole company. The end result of such LBOs is that the business division becomes a private company rather than part of a public company. One common example is when a corporation decides that a division does not fit into its plans and wishes to divest, and a management team or investor group decides to purchase that division. This was done, for example, by AXA Private Equity in 2013, which was previously a division of France-based AXA Investment Managers. The deal valued AXA Private Equity at approximately €500 million and employees of the new company owned 40%. Post deal, the company renamed itself Ardian to finalize the split with the former parent company.

Why do LBOs make sense? By going private, the separation of ownership and control is eliminated; managers focus even more attention on eliminating costs and this often creates the extra earning capacity necessary to service the very high levels of debt incurred in the purchase. Management in most LBOs are clearly incentivized to work harder to increase sales and revenues, make cost cuts that have been previously overlooked, and generally “sweat” the assets.

The capital structure of an LBO may also lead to greater efficiencies. Management equity in LBOs is on average higher than in publicly-held companies. Those managers have greater incentives to monitor revenues and expenses more closely than the widely distributed equity base typical for most public firms. There is also more focus on the cash flow, and correspondingly no longer a need to focus on quarterly earnings for securities market reporting to outside investors. This focus on cash flow is critical to the success of a highly leveraged firm, as it is cash that is needed to service debt, as opposed to earnings per share to justify dividends or satisfy equity analysts. Firms that have been taken private in an LBO often try to minimize taxable income to lower taxes, thus increasing after-tax cash flows.

Increased debt can therefore be a benefit to corporations, despite the perception of many analysts to the contrary. Debt can be a useful constraint that causes firms to be more efficient. High cash flows and low debt payments can lead management to make less efficient capital investment decisions. With the increased debt after an LBO, there is less freedom to waste money.

In fact, the characteristics that make a company (or division of a company) a potentially desirable LBO candidate – or indeed an attractive takeover target – are the same factors many would use to describe a well-run company (see box). The external perception that a company has these characteristics will make it more likely to be an acquisition target – often unsolicited.

Even more money is often to be made when a company does a reverse LBO. This is when a firm that has gone private in an LBO goes public again at a later date. It is somewhat obvious (from the manager's perspective) that a good time to do the LBO is when the market is down and the company is cheap; after the market has started to recover and the company's major problems are cleaned up, the company can go public again or be purchased by another firm.

Highly leveraged funds and internal management teams are only two potential buyers other than the traditional strategic corporate buyer, but as can be seen from the example of the LBOs above, there is significant money to be made from deals that can be structured properly.

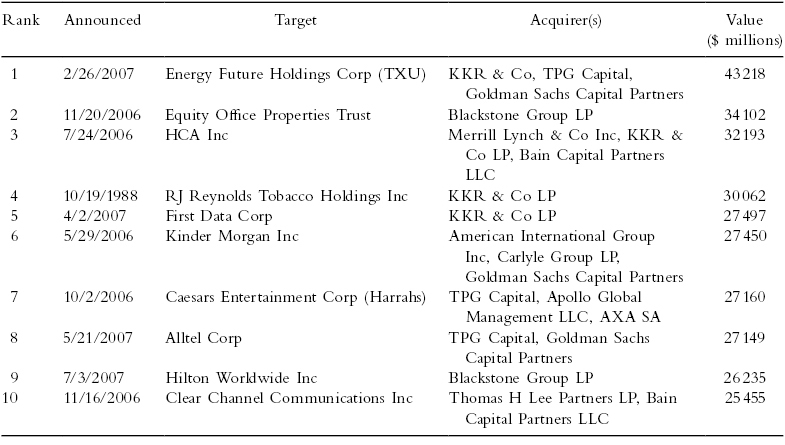

Hedge Funds and Venture Capitalists

The competition for deals heated up in the most recent merger wave (2003–2007) with private equity and venture capital houses a major driving force (see Table 3.1); during some periods, these so-called “financial sponsor” buyers have almost been as much a factor in the market as the corporate “strategic” buyers. When it happens, this competition for deals has the potential to raise the price of target companies – emphasizing once more the need to have full business intelligence to allow for sharp-pencil valuations and the information to provide to shareholders that the valuation was appropriate. It is also worth noting that as competition increases, the need to complete the deal speedily increases in order to avoid having other buyers enter the competition for the target. Speed enhances the chance that something will be overlooked – a classic intelligence failure.

Table 3.1: Top 10 private equity deals. (source: Bloomberg)

More recently, another dimension has been added to the M&A field provided by the ever-increasing hedge fund community. Hedge funds have given corporates some support by acting as arbitrageurs in M&A deals; by securing stakes in companies that are undervalued, they bring companies into play but also provide corporates a chance of competing against well-funded private equity funds. Their activity has also been growing. Hedge Fund Research estimated that in the year to mid-2013, event-driven hedge fund activities (largely driven by M&A and certain other types of corporate announcement) have delivered returns that exceeded other strategies. As with some other private investors, they are largely unregulated, although there is currently discussion that regulations in some form be extended to include these funds.

The hedge funds have deep pockets with good liquidity from which they can outbid private equity firms. Indeed, while they are considered a threat by private equity firms, their role as arbitrageurs is even more important. Understanding their role is critical in any deal, and there will be some examples later where the hedge funds have influenced the outcome of some very high profile transactions. Unfortunately for the intelligence-gathering function, these funds also often act outside the corporate radar screen, holding their shares below the disclosure threshold until they choose to act. This disclosure threshold, also known as a “toehold,” will be discussed further in Chapter 9. Arbitrageurs will be discussed in Chapter 6.

Business Intelligence in the M&A Process

Clearly corporate strategies have been forced by the private equity world to use ever more structured and disciplined moves directed at realizing value from acquisitions. There is no doubt that over the last decade, corporations have become much more sophisticated in their approach to deal making and implementation. This push towards more robust processes has also been driven by the increasing accountability and transparency required of boards because of the 2007/8 financial crisis, as well as some high profile failures of supervision at board level (Enron, Parmalat, Arthur Andersen, and the Royal Bank of Scotland, to name just a few), have raised the importance of good corporate governance. Corporate boards are increasingly required to bear more responsibility and become more involved in assessing risk management practices; conversely, senior executives are facing more detailed questioning about their strategy and decisions. All these processes can be made extremely robust and explicit through a business intelligence approach, and with the support of such tools as Scenario Planning, which was discussed in Chapter 2.

It is also important to remember that the selling and buying process must be grounded in good information. For example, in buying a company, the first and most important step is to understand the business(es) of that target company. As all businesses and deals are different, the more time spent at this stage in a deal, the more likely there will be a successfully negotiated deal. This will even further contribute to post-deal success, as will be discussed in Chapter 10. This understanding of the business includes knowing the following:

- The industry in which it operates

- The history of the company being sold, including any recent changes in management or acquisitions that may not yet be fully integrated

- The financials and principal value drivers to profitability.

There are other issues to be investigated too, as will be discussed in Chapter 7, Due Diligence.

From the perspective of business intelligence, the entire M&A deal process may rightfully be considered a “field day” for corporate spies, given that so much critical information is unwillingly and unwittingly revealed throughout the cycle of a deal. Whether stolen or mistakenly given away by staff, the loss of confidential and critical information to rivals is costly to any firm in any marketplace at any time. Divulging competitive information to another player can ultimately inflict serious damage on a company if a deal is not signed, allowing an “acquirer” to walk away with a significant amount of useful information on a competitor that can subsequently be turned against them. Thus, whether entered into for genuine commercial reasons, or as a tool by which to gather information on competitors, the M&A process may result in the loss of confidential and critical information to various parties, requiring vendors to resolve first what should be revealed to whom and when in the process.

Whether carried out by trusted insiders, business partners, employees, or even government officials, espionage and the loss of intellectual property to competitors can and does often play a central role in the entire M&A process as people try to access information by a variety of means for their own advantage. Given the state of flux that parties to an M&A deal often find themselves in, it should come as no surprise that companies become easy targets for exploitation in one shape or another. Indeed, one case in point that demonstrates this vulnerability was the acquisition of DLJ by Credit Suisse First Boston (CSFB) in 2000, when prospective buyers – able to view production figures for the target's sales staff – selectively lured away individuals to the detriment of CSFB. Likewise, the acquisition of Bankers Trust by Deutsche Bank in 1999 also resulted in a large number of high-level departures from the combined firm with whole teams being poached to work for rival banks; this has been a problem within investment banking since the early 1990s, not just at Deutsche Bank. In fact, Deutsche Bank itself was the poacher of several large teams from S.G. Warburg, Merrill Lynch, and Morgan Stanley during that period.

Clearly, given the level of business intelligence “victimization” within the M&A process and the significant vulnerability of firms to the loss of critical information exposed as part of the due diligence process, companies need to protect and guard their assets more carefully, preventing unnecessary leaks and slips throughout the M&A process. This will be covered in greater depth in Chapter 7. However, it should be noted here that the UK financial authorities themselves admit that there is suspicious trading activity preceding 19.8% of all deals in the UK in 2002, and the previous year, it was over a quarter of all deals. Most analysts will say that the suspicious trading activity is due to the leaking of inside information.

While adhering to certain tenets of secrecy (such as confidentiality agreements, non-disclosure agreements, project code names, secure data rooms, and information divulged on a “need-to-know” basis), nevertheless many of the parties connected with a material corporate event such as an M&A deal may also profit from information seepage. While bankers and other advisors may wish to build up tension or interest in a deal through leaks to prospective rivals in order to inflate a target's auction sale price (thereby also achieving a larger commission-based fee for themselves), others, including potential acquirers, may also wish to release non-public information to the outside.

The business media are forever trying to scoop potential M&A deals for their headlines. They serve as a vehicle by which parties to a transaction can leak stories in order to test out institutional shareholders' responses to a potential deal. In a study conducted in 2013 by the M&A Research Centre at Cass Business School for Intralinks which covered the period from 2008 to 2012, the percentage of deals globally that exhibited some significant pre-announcement trading activity was approximately 8%. As noted above, the principal market regulator in the UK, the Financial Conduct Authority, itself announced that they had identified that almost 20% of all M&A deals had abnormal trading activity in 2012, albeit this figure is down from the prior year and is the lowest figure since 2003. This decline can be attributed to increased enforcement by the regulator as well as the continuing lower level of deal activity.

All in all, as these examples clearly demonstrate, given the level of leakages involving M&A deals and their effect on vendor and target share prices, it is no wonder that executives (when it is in their favor!) try everything they can to prevent such “porosity” – including the use of in-house expertise whenever possible, reducing the amount of pre-deal work, and the drafting of confidentiality agreements between parties. Of course, there will be times as well when well-placed “leaks” of information, or even the inference that such leaks may take place, will serve one of the parties in the negotiation. The authors and many other market practitioners believe that most leaks are deliberately perpetrated by one of the parties to the deal who think's that the leak will advance their position or negotiating power.

Conclusion

There isn't a time during the takeover deal process when it isn't necessary to be alert to the changing external and internal environments through the effective use of the business intelligence techniques discussed earlier. Many M&A practitioners have understood the value of these techniques and the value of employing managers and staff experienced in their use, but have usually limited their application to the due diligence process. This is a mistake. Competitive advantage can be gained by applying these techniques throughout the deal process and in any type of merger or acquisition, whether friendly or hostile, whether structured as an acquisition or a management buy-out, or whether familiar as in a merger with a close competitor or alien as with a diversification into an area where the company has no prior experience.