CHAPTER 1

The Need for Intelligence in Mergers and Acquisitions

Mergers and acquisitions are an integral part of the global strategic and financial business landscape, whether one is part of the acquiring company, the target, a competitor, an advisor (including investment bankers, accountants, lawyers, and many others), an investor, a regulator, or someone living or working in the neighboring community.

Although fluctuating widely from periods of peaks and troughs of merger activity, the baseline size and growth of mergers is clear. In fact, the “slow” period of activity in 2002 was well in excess of the “peak” of activity in the late 1980s. Even the downturn following the financial crisis of 2007 and 2008 saw levels of M&A activity remaining well above $2 trillion annually for at least six years, which isn't much of a downturn when compared to levels only a dozen years earlier. At the time of writing, it is unclear whether M&A deal volume will increase or not from that level but, whether up or down, the absolute number of deals will certainly remain high.

Yet despite this impressive level of activity, mergers and acquisitions are often misunderstood and misrepresented in the press and by those who are engaged in each transaction. Deals, especially when hostile, cross-border, or among large companies, might be front-page news (and interestingly there are some days when every story covered on the first page of the Financial Times is about an acquisition), yet there is a great deal of conflicting evidence as to whether they are successful or not. This can sometimes be a function of senior management focus: for example, when we have observed boards during M&A deals, they often appear to spend more time discussing the new corporate name or the color and design of the new corporate logo than the key decisions regarding senior management positions or culture. Fortunately, our own research has shown improved performance from companies that make acquisitions, especially since the merger wave that began in 2003, so perhaps the focus on key integration decisions is changing.

Why do the public and many managers still believe that most deals fail? Partly, this is due to the propensity of journalists to write about the less successful deals. These make for great stories in the financial and popular press. Together with the (outdated) conventional wisdom that most deals fail, this creates a negative bias for the financial community that can result in a form of groupthink whereby investment managers and other equity analysts, as well as individual investors, are more likely to ignore positive information and mimic each other's negative investment decisions. This herd behavior has certainly resulted in many M&A deals not being accurately assessed on their own merits. In M&A, bad news appears to be a more popular subject with readers, who are more interested in value-destroying deals, than those executed smoothly, successfully, and often quietly.

That said, there do seem to be some inviolate truths about M&A deals:

- Many fail to deliver the promised gains to shareholders.

- Boards, CEOs, senior managers, and advisors pursue deals for personal reasons.

- Success with one deal doesn't guarantee success in the next deal.

- Deals have a momentum of their own and this means that they don't get dropped when they no longer make sense.

- The deal doesn't end when the money changes hands; in fact, that point marks the start of the most difficult stage of a deal, the tough integration process that few get right.

Indeed, given the conventional wisdom that most deals fail, it must be that boards and chief executives either treat that conventional wisdom as applying to someone else or as hyperbole perpetuated by consultants and other advisors as justification for their services. Or it may be a matter of corporate “hubris” that refuses to see what is obvious and plan accordingly.

Some M&A failures have been dramatic. The AOL/Time Warner deal lost 93% of its value during the integration period as the internet service provider merged with the publishing company in an attempt to combine content with delivery. VeriSign, another internet-related services company, lost $17 billion of its $20 billion acquisition of Network Solutions in 2000, and its stock fell 98%. Failures are not unique to the United States. The Royal Bank of Scotland, together with Banco Santander and Fortis, purchased ABN AMRO in 2007; that deal contributed to the failure of Fortis and the semi-nationalization of RBS. It was pursued despite the signals in the marketplace which led to the financial crisis. Another classic example of failure – and one where the very basic elements of business intelligence were ignored – is Quaker Oats, a food and beverage company founded in 1901. In the brief case study that follows, look at the first word of the penultimate paragraph. It is the key identifier of an intelligence failure. The word is “following.” Incompatibility of cultures is one of the biggest post-acquisition killers.

In perhaps one of the more ironic stories of acquisition failure, in late 2013, G4S, a UK-based company which bills itself as the “world's leading international security solutions group,” blamed “a short-term and over-aggressive acquisition strategy for a string of scandals,” according to the Financial Times. The new CEO announced that the company was considering disposing of 35 underperforming business, some of which had only been recently acquired. Brilliant that a security company that conducts due diligence and other intelligence-related functions for its clients has effectively admitted that it was no good at its own intel!

One challenge in trying to determine the success of an acquisition lies in how to define “success.” Is it shareholder value? If so, over what period? Or should one look at sales growth? The ability to retain key customers and market share? Employee retention? Cost savings? And how would the company or companies have performed if they had not merged? Perhaps, as some have suggested, success should be defined by the publicized goals of the merging companies themselves and then measured against the achievement of those stated objectives.

No matter how it's measured, a fair degree of consistency has emerged in the results of studies that examined M&A “success” through the 20th century. Essentially, all of the studies found that well over half of all mergers and acquisitions should never have taken place because they did not succeed by whatever definition of success used. Although many studies based on deals conducted in the 1980s and 1990s found that only 30 to 40% were successful, more recent studies have found that this success rate is improving, yet still only to around the 50% level. Yet most companies that have grown into global giants used M&A as part of their growth strategy and without those acquisitions and mergers would not be the size that they are today.

This paradox raises the following questions:

- Can a company become a large global player without having made acquisitions?

- Is organic growth sufficient to become a leading global or even a leading national player?

The challenge for management is to reconcile the relatively low odds of deal success with the need to incorporate acquisitions or mergers into their growth strategy, or to figure out how to beat the odds and be successful in takeovers. This is where business intelligence techniques are essential.

Prior experience may not be a predictor of success, although some studies have shown that acquirers do better when making an acquisition that is similar to deals they have done previously and that serial acquirers – those that do two or more significant deals a year – also have a better success rate than firms that are less frequent acquirers of other companies. Indeed, these serial acquirers have a great impact on the M&A market. Accenture, in their 2010 study of serial acquirers, found that, although serial acquirers represented only 9% of all acquiring companies, they conducted 35% of all the deals as measured by number of deals and 44% of the deal volume measured by size of deal. We will provide many examples in this book of these serial acquirers, given their importance to the market. It does appear to be true that acquirers who are active, frequent buyers and who are willing to do complex and big deals outperform those who are inactive and conservative. This does imply that a set of best practices exist, as we will discuss in this book. Maybe practice really does make perfect, or at least better.

Here again the utilization of specific intelligence is central. Many studies have shown that relatively inexperienced acquirers might inappropriately apply generalized acquisition experience to dissimilar acquisitions. The more sophisticated acquirers would appropriately differentiate between their acquisitions. In a deal that will be discussed later, VeriSign appears to have failed with its 2004 purchase of Jamba AG despite having made 17 other acquisitions in the prior six years, many in related internet businesses. Intelligence cannot, therefore, be taken for granted.

Different Types of Mergers and Acquisitions

There is even some confusion about the terminology used. Many have questioned whether all mergers and consolidations are really acquisitions. This is because the result – sometimes as much as a decade later – is that the staff, culture, business model, or other characteristics of one of the two companies becomes dominant in the new, combined organization.

Clearly, care should be taken in using the terms “merger,” “acquisition,” “consolidation,” and other related words. In practice, however, these terms are used interchangeably. Additionally, “takeover” is a term that typically implies an unfriendly deal, but will often be used in the popular press when referring to any type of merger or acquisition. In this book, we will be as precise with the terminology as possible. Specifically, this means that when the term “acquisition” is used, it refers to a deal in which one company (usually the larger one) acquires another company: the buyer remains as a legal entity, albeit larger, and the target company ceases to exist as it is subsumed into the acquirer. “Merger” is when two companies come together to create a new, third, company; when that is done, the two previous companies cease to exist. As will be discussed in Chapter 10 on post-deal integration, there are rarely true mergers, as over time one of the two companies will dominate the new company. It should also be noted that there are many more acquisitions than mergers: of all deals since 2000, less than 10% are structured as mergers.

There are three major types of mergers/acquisitions which are driven by different goals at the outset and raise different issues for the use of business intelligence:

- Horizontal deals take place between competitors or those in the same industry operating before the merger at the same points in the production and sales process. For example, the deal between two automotive giants, Chrysler in the US and Daimler, the maker of Mercedes cars and trucks, in Germany, was a horizontal merger. The many consolidating deals in the mobile telecommunications industry in recent years would also fall into this category.

In horizontal deals, the managers on one side of the deal will know a lot about the business of the other side. Intelligence may be easy to gather, not just because there will likely be employees that have moved between the two companies over time in the course of business, but also because the two firms will most likely share common clients, suppliers, and industry processes. These deals often include cost savings (frequently described as “synergies”) as a principal deal driver because it is more likely that there will be overlaps and therefore redundancies between the two companies. These synergies can be both on the expense side, such as reductions in overlapping factories or staffing, and revenues, such as products that can be packaged together. - Vertical deals are between buyers and sellers within the same industry, and thus represent a combination of firms that operate at different stages of the same industry. One such example is a merger between a supplier of data and the company controlling the means through which that information is supplied to consumers, such as the merger between Time Warner, a content-driven firm owning a number of popular magazines, and AOL, the world's largest internet portal company at the time of their merger. There is often less common knowledge between the two companies in a vertical deal, although there may still be some small degree of common clients and suppliers, plus some previously shared employee movement. Depending on the perspective of the firm, the vertical merger will either be a backwards expansion toward the source of supply or forwards toward the ultimate consumer. The 2003 acquisition of TNK (a Russian oil company with large oil and gas reserves but little Western refining capability or retail marketing) by BP (which had declining reserves and strong global marketing and refining operations) is one such example. We will visit this acquisition again, as well as the separation of the two companies in 2013.

- Conglomerate deals are between unrelated companies, not competitors and without a buyer/seller relationship (for example, the 1985 acquisition of General Foods, a diversified food products company, by Philip Morris, a tobacco manufacturer). Conglomerate deals do not have strategic rationalization as a driver (although often cost savings at the headquarters level can be achieved, or in the case of Philip Morris, it wished to diversify risk away from the litigious tobacco industry). This type of deal was common in the past, but has fallen out of favor with shareholders and the financial markets, although when they do occur they can benefit greatly from the more creative uses of business intelligence. For example, detailed scenario planning, involving simulations based on high quality information, can identify unforeseen problems that can drive such deals and provide a logical rationale.

Deals are either complementary or supplementary. A complementary acquisition is one that helps to compensate for some weakness of the acquiring firm. For example, the acquiring company might have a strong manufacturing base, but weak marketing or sales; the target may have strong marketing and sales, but poor quality control in manufacturing. Or the driver may be geographic: when Morgan Stanley made a bid to purchase S.G. Warburg in 1995, it wanted to complement its powerful position in the US market with Warburg's similar position in the UK and Europe. Similarly, Kraft, when it purchased Cadbury in 2010, sought Cadbury's strong market position in India, and several other emerging markets, as a complement to its own dominant position in the US. A supplementary deal is one in which the target reinforces an existing strength of the acquiring firm; therefore, the target is similar to the acquirer. A good example of such a deal would be when one cell phone company buys another, such as Sprint purchasing Nextel in 2005 to form Sprint Nextel. Most supplementary deals are horizontal.

The final descriptive distinguishing factor about a deal is whether it is hostile or friendly. A hostile deal is one in which the board of directors of the target company rejects the unwelcome bid. In these situations, the bidder expects to go directly to the shareholders to overrule the board. Because of the requirement that a hostile deal is one where the shareholders disagree with management and the board, hostile deals can only occur with public companies where management does not own over 50% of the shares. For all deals since 2000 where the target has been public, only 1% have been hostile at the point where the shareholder vote was taken. Since these are often large deals, hostile deals are around 7.5% of the total on the basis of value.

It is possible for a bid to be friendly, with the support of the board, but then turn hostile if there is a change in the board's position. This can happen when the target's board uncovers negative information about the buyer or if the terms of the deal change to make it less attractive (as might happen if the buyer's share price declines dramatically in a deal in which the target was being paid with shares). Similarly, a hostile bid can turn friendly, which typically occurs when the buyer increases its purchase price or changes the terms (perhaps replacing a share offer with full or partial payment in cash or agreeing to retain the target's management). For example, when Kraft attempted its purchase of Cadbury, the bid was unsolicited and initially hostile as the Cadbury board twice rejected Kraft's formal bids. Ultimately, Kraft improved the terms of its bid with a higher price and a larger proportion of the consideration being in cash, with the result that the Cadbury board changed its recommendation to supporting the deal.

The Merger Waves

Merger activity tends to take place in waves – times of increased activity followed by periods of relatively few acquisitions. The waves have been growing in size: the peak of the most recent wave (the Sixth Merger Wave, as discussed below) had its most active year with announced deal volume of $4.7 trillion in 2007. The previous wave had topped out at $4.3 trillion in 1999, and the wave before that with a peak of only $0.9 trillion in 1988. In fact, the largest deals of the most recent merger wave never exceeded those of the prior merger wave, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Each wave has been stimulated by events outside the merger world, but those external events have had a significant impact on the level of merger activity. Each wave is sharply distinguished from earlier waves, with creative new ways of consolidating companies and defeating the defenses of targets, although each builds on the merger techniques and other developments from the previous wave.

There is also the tendency, as with the military, of preparing to fight the last war's battles. Just as the Maginot Line was bypassed by the Third Reich's Panzers as they rolled through Belgium and into northern France at the start of World War II, it is not sufficient for a company to have out-of-date takeover defenses. Strategic initiative or power does not guarantee success for the bidder, as the United States learned militarily in Vietnam in the 1960s and in Iraq in the 1990s and 2000s. The parallel in business usually means relying too much on a large checkbook and first mover “advantage,” as Sir Philip Green discovered in 2004 when trying unsuccessfully to take over Marks & Spencer (M&S). He had not planned for the strong defense put up by M&S, including the hiring of a new CEO in the middle of the takeover battle.

Merger activity can be likened to the Cold War arms race, in which one country's development of new weapons stimulated the development of more sophisticated defensive systems, thus forcing the first country to make further advancements in their offensive weapons to remain ahead. In the M&A arena, as acquiring companies have developed more sophisticated tools to make the acquisition of companies more certain, faster, easier, or less expensive, the advisors to those target companies have designed stronger defenses for their clients. These defenses have then stimulated further activity to create better acquisition methods. Just as with the international arms race in the 1950s and 1960s, the process becomes more complicated and expensive for all the players.

Knowledge of previous takeover techniques is therefore important for any bidder or target – and is a critical aspect in the application of business intelligence. The development of these tactics has concentrated in the six major merger waves since the beginning of the 20th century, and focused during much of that time on the United States as the largest and arguably most open M&A market in the world. In most cases, the new developments in M&A were first tried in the US and then “exported” to other countries or regions, although before the 1990s the major economic regions had somewhat different waves but often driven by similar factors. Since the 1990s, the merger waves have been truly global.

The first merger wave began in 1897 and continued through to 1904. It started in the United States after the Depression of 1893 ended, and continued until the 1904 stock market crash, with a peak between 1898 and 1902. This merger wave featured horizontal deals (over three-quarters of the total) often resulting in near monopolies in the consolidating industries: metals, food, oil, chemicals, trains, machinery, and coal. It was therefore also known as the “monopoly merger wave.” Some of the companies formed from this wave in the US have remained global powerhouses and included Dupont, Standard Oil (controlled 85% of the US domestic market), American Tobacco (controlled 90% of its market), General Electric (GE), Eastman Kodak, and US Steel (controlled 75% of its market). There was a similar trend in other markets, particularly Germany, France, and the United Kingdom.

The second merger wave was from 1916 until the Great Depression in 1929. The growth of this merger wave was facilitated by cooperation among businesses as part of the Great War (World War I) effort, when governments did not enforce antitrust laws and in fact encouraged businesses to work more closely together. For the first time, investment bankers were aggressive in funding mergers, and much of the capital was controlled by a small number of investment bankers (most notably J.P. Morgan). The role of investment bankers in driving the deal market continues today.

Over two-thirds of the acquisitions in the second merger wave were horizontal, while most of the others were vertical (thus, few conglomerate mergers). If the first merger wave could be characterized as “merging for monopoly,” then the second wave could best be described as “merging for oligopoly.” Many of these deals created huge economies of scale that made the firms economically stronger. Industries that had the most mergers were mining, oil, food products, chemicals, banking, and automobiles. Some of the companies created in the US in this period were General Motors, IBM, John Deere, and Union Carbide.

The third merger wave occurred from 1965 to 1969. Many deals in this wave were driven by what was later determined to be the irrational financial engineering of company stock market earnings ratios (similar in many ways to the exuberance of the dot.com era 30 years later). This wave was known as the “conglomerate merger wave,” as 80% of all mergers in the decade 1965–1975 were conglomerate mergers. A classic example is the acquisition by ITT of companies as diverse as Sheraton Hotels, Avis Rent-a-Car, Continental Baking, a consumer credit company, various parking facilities, and several restaurant chains. Clearly, ITT would not be able to integrate these companies at the production, business, or client levels, so there was little in cost savings or strategic rationale that drove the deals despite claims of management efficiency at the headquarters level; instead, the growth of ITT was blessed by the market with an award of a high stock price!

One reason for such conglomerate deals was the worldwide growth after World War II in stronger antitrust rules (or the more vigorous enforcement of existing antitrust and monopoly regulations), thus forcing companies that wanted to expand by acquisition to look for unrelated businesses. The beginning of the end was the fall of conglomerate stock prices in 1968.

The fourth merger wave was from 1981 to 1989. During this wave, hostile deals came of age. Generally, the characteristics of this merger wave were that the number of hostile acquisitions rose dramatically, the role of the “corporate raider” developed, anti-takeover strategies and tactics became much more sophisticated, the investment bankers and attorneys played a more significant role than they had since the second merger wave, and the development of the high yield (“junk”) bond market enabled companies to launch “megadeals” and even purchase companies larger than themselves. This last trend contributed to the high number of leveraged buy-outs with excessive use of debt and companies going private. Assisting this merger wave was relaxed antitrust enforcement, especially in the US under President Ronald Reagan and in the UK under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

The fifth merger wave (1994–2000) was characterized by consolidations of industries and globalization. The dot.com boom and bust also occurred during this wave. Many “strategic” consolidations unfortunately failed to deliver on promised gains, such as lower costs and greater synergies, and ended with the decline in stock prices worldwide beginning in 1999/2000. Nevertheless, there were a large number of significant deals during this wave in the following industries:

- Oil (BP/Amoco, Exxon/Mobil, Total/Petrofina)

- Financial services (Citicorp/Travelers, Deutsche Bank/Bankers Trust, Chase Manhattan/J.P. Morgan)

- Information technology (Compaq/Digital Equipment, Hewlett-Packard/Compaq)

- Telecommunications (Mannesmann/Vodafone, SBS Communications/Ameritech)

- Pharmaceuticals (Glaxo/Wellcome)

- Automotive (Daimler Benz/Chrysler)

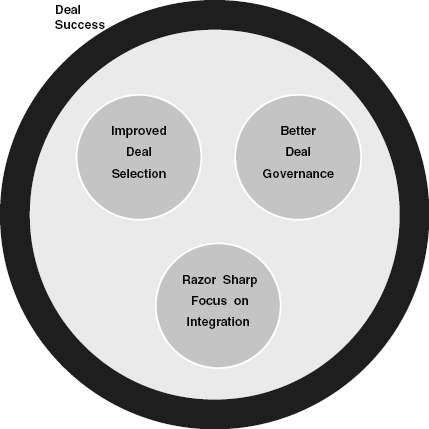

The sixth merger wave began in 2003, less than three years following the end of the previous cycle, and ended abruptly as the financial crisis unfolded in 2008. That sixth merger wave was truly global and saw more focus on strategic fit and attention to post-deal integration issues. It was heavily influenced by the corporate governance scandals of the early years of the new millennium and the resulting laws and regulations that had been passed – most notably the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in the United States. It was also during this wave that the success rates for M&A deals began to improve. This was largely driven by three factors, as shown in Figure 1.2, which comes from a presentation that Towers Watson (then Towers Perrin before their own merger in 2010 with Watson Wyatt) developed together with Cass Business School.

An additional change in the sixth merger wave was the rise in activity by financial buyers (hedge funds, private equity funds, and venture capital funds) who do not and cannot have strategic interests as the primary driver. These funds purchase large stakes in companies and then either purchase the remaining part of the company or force a reorganization through the exercise of their shareholder rights. In some cases these shareholder actions have stopped deals from taking place where the funds exerted pressure on management as they felt they could achieve higher returns in other ways, such as the return of cash to shareholders in the form of a special dividend or where the intrinsic growth potential of the company was seen to be excellent. This was the case in early 2005 when the Deutsche Börse was forced to withdraw its proposed takeover of the London Stock Exchange, despite the fact that the board of the Deutsche Börse had already approved the deal. More on this deal later. Financial buyers represented up to 40% of the M&A market in the US at one point before the sixth merger wave ended.

When will the next merger wave start? This has been the discussion among many market practitioners since the financial crisis in 2008. Most market practitioners are optimists, and have been forecasting the return of strong M&A market activity almost every year since. When it will occur is still uncertain. That it will at some point reoccur is almost a certainty. History will repeat itself, and not just in merger waves. Other ways in which this happens in M&A are the reasons and rationales driving the deals. Just as understanding the history of M&A is helpful in planning today's deals both offensively and defensively, understanding the drivers to deals is also critical.

Reasons for M&A Deals

Some of the reasons for acquiring or merging may have started to become clear from the earlier discussions in this chapter, such as the need to control a source of raw materials in a backwards vertical acquisition, as BP announced when it acquired TNK. But it is usually necessary to dig deeper than the press statements from the parties involved. Very often the publicly stated reasons are quite different from the underlying strategic rationale (assuming such a rationale really existed at the time of the deal's genesis, as some deals are just opportunistic).

Numerous theories have been put forward regarding the reasons for mergers and acquisitions. Whether “… caught up in the ‘thrill of the hunt,’ driven to complete deals as a result of internal company politics, management bravado, or the need to boost divisional key performance indicators in order to reach bonus targets …,” as suggested to us by Sarah Byrne-Quinn, Group Director of Strategy and Business Development at Smith & Nephew, deals are often motivated by personal and financial as opposed to strategic considerations. Either way, to avoid peripheral issues taking center stage, organizations need to remain open minded when pursuing a deal, building teams which question assumptions on an ongoing basis and remain focused on the overall strategy for the company, while being motivated by the underlying “quality” of an acquisition at the right price.

There are often multiple reasons given, sometimes conflicting and overlapping. Generally speaking, the most common reasons used to justify a merger or an acquisition are claims of the need to increase market power, efficiency (in various forms, such as economies of scale), pure diversification (often because the core business is in a declining industry), information and signalling, agency problems, managerialism and hubris, and taxes. Each of these is discussed briefly in the box below.

Regardless of the drivers to the deal and the supporting analysis, the deal will also need to be sold – and justified – to a number of parties. Most important will be the owners of the company, which, in the case of a public company, will be the shareholders. As Michel Driessen, Senior Partner, Corporate Finance at EY, told us when speaking about the financial justification, “not only will buyers have to convince their own boards that an acquisition makes sense, they will have to share their analysis with the market at large. Key audiences for these public estimates of synergy benefits are shareholders and lenders, who use the information to help support their own valuations of the deal. Getting it wrong could undermine the buyer's credibility and make it harder to justify acquisitions in the future.”

Public Sector Mergers

Although the focus of this book and the examples shown are heavily weighted towards the private sector, the principles discussed apply to public and non-profit sector mergers as well. Certain differences should be noted. It would be a rare public sector deal that was hostile as these mergers are often the result of both long consultation periods and, at least in the democratic world, a long process driving toward consensus. That isn't to say that public sector mergers cannot be driven by one individual – such as New York City's Mayor Rudolph Giuliani's three attempts to merge two health departments in the State of New York, which were ultimately legislated on in November 2001. But even when initiated by one individual or group, the ultimate decision usually follows a democratic process.

Public sector mergers are, by their very nature, more political and often driven by politicians and government ministers. As governments change and new leaders come into office, one consideration is whether they can demonstrate change through the merging or de-merging of departments, offices, and public services. Of course, this is not to say that the private sector is immune to the demands of politicians in regard to mergers or acquisitions. One only needs to look at the pressure that certain banks came under when the financial sector was imploding in 2008 (J.P. Morgan in the case of their acquisitions of failing banks Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual, Bank of America's purchase of Merrill Lynch, and Lloyds TSB's purchase of Halifax Bank of Scotland).

Public sector mergers are becoming more common. Indeed, one of the regulators of the M&A industry in the UK is even merging, with the merger of the Competition Commission and the competition functions of the Office of Fair Trading into a single Competition and Markets Authority in April 2014. Many of these mergers have been driven by budgetary pressures and the increases in demand for accountability that have forced governments and non-profit organizations to improve their performance and achieve key targets to satisfy the public demand for their services, as shown in the example from the UK's National Health Service (NHS) in the box.

As with private sector acquisitions, public sector mergers can also be triggered by external shocks. The terrorist attacks in the United States on September 11, 2001 led to a reorganization within the federal government of the US whereby some 22 departments (including border patrol, immigration screening, and airport security) were combined to form the Department of Homeland Security. This was akin to a similar reorganization that took place in the US after World War II, when the War Department became the principal component of the newly created Department of Defense. These mergers were driven by demands to improve the quality of management and services, as well as the need to increase efficiency, coordination, accountability, and cost savings. However, as is shown in the box below, the merger of public sector departments is even older.

The third sector – charities, including volunteer and other non-profit organizations – can also be active in merging and acquiring, often for many of the same reasons as private sector companies. These reasons often include the need for increased scale and scope, greater efficiencies in operations through economies of scale, the acquisition of management and organizational talent, and even for particular assets (such as donor lists). Local and central governments are under pressure to reduce their direct social care costs because of budgetary pressures, and this has led to a trend towards a greater reliance on charities and other voluntary organizations. In addition, in the past some of these organizations received funding directly from the state, which is now being reduced. These two forces are combining to increase pressure towards having increased size and scope, thus leading to the need for consolidation in the charity industry.

Conclusion

From whichever perspective one views M&A activity – whether economic, strategic, financial, managerial, organizational, or personal – corporate takeovers should permit firms and organizations to promote growth and offer savings while achieving a significant and sustainable competitive advantage over their rivals within the global marketplace. With new markets opening at an unprecedented pace, the evolution of the competitive landscape means that acquisitions must be made in order for the company to succeed in filling the product, geographic coverage, and talent gaps. As such, an acquisition provides senior management or a board of directors with the opportunity to grow more quickly than would otherwise be possible, with access to new customers, new technologies, greater synergies, and the power that comes with size. It is also an adrenaline rush for all involved at the top, despite the possibility that many will be made redundant, including some of the senior managers driving the deal.

M&A deals are risky. A full merger or acquisition should be attempted only as a last resort. (We will briefly discuss the alternatives to M&A later, in Chapter 5.) Full integration may take years to complete and will necessarily include its own expenses, and therefore the payback and other financial benefits may be a long time coming. Current employees, customers, and suppliers may be neglected. There's the tendency to overpay when acquiring another company, not just because of the auction effect if there are multiple bidders for the target, but also because the sellers are motivated to get the highest price possible and they are the ones who know their own company best – where the skeletons are hidden and which assets are most valuable. For bidder and target alike, it is critical to use business intelligence efficiently. There are just too many areas where mistakes can be made in the acquisition of another company.

Merging or acquiring can be a threat to the current shareholders or a great opportunity. The outcome is never preordained and certainly is an excellent business application of Prussian Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke the Elder's maxim that “No battle plan survives contact with the enemy.” It is necessary to crawl carefully through the minefield, using as much intelligence as possible to avoid the potential and often very real dangers.