CHAPTER 11

Post-Deal Review

Do firms learn from previous acquisitions? The easiest intelligence to collect and use is the information that already exists in-house. Such knowledge can come not only from a company's own prior deals, which are most likely to be relevant and applicable to the company's next deal, but second-hand by studying transactions of other firms, especially in the same industry, although useful information can also often come from further afield. Such organizational learning can potentially lead to an improvement in acquisition success rates. It is an area where the use of the intelligence function is critical in order to gain the competitive edge.

There is another reason why this improvement in acquisition success is important for a company. This is so that an acquisitive company can build up a reputation for being a successful acquirer. Companies for sale will seek out such buyers, knowing that they will be treated better post-deal. In the fairly common situation discussed in Chapter 3, where there are limited private auctions or bilateral discussions, there is a need for an acquirer to be invited. For example, in late 2013, according to The Wall Street Journal, MBK Partners, a South Korean private equity firm, sent out so-called “teaser letters” to only 40 potential bidders for a bottle-making company that it was planning to sell. If the business is of possible interest, you’d want to be on that invitation list.

M&A Skill as a Core Competency

For some companies that acquire other companies frequently, M&A is one of their core competencies and competitive advantages. These companies, such as General Electric, GlaxoSmithKline, Cisco, and Intel, even publicly trumpet their M&A expertise. Companies that have proven success in acquiring others do have a competitive advantage over those which, for whatever reason, have decided that they will only grow organically, or who have failed at prior acquisitions and not learned from those mistakes, and are, therefore, doomed to repeat them. A study by McKinsey released in early 2012 argued that the most successful acquisition strategy in terms of shareholder return is to carry out what it calls a “programmatic approach.” This is when the acquirer executes a number of smallish deals that in aggregate make up 19% or more of the company's market capitalization. These deals, it says, provide a median excess return of 2.8% over the market. In contrast, large-scale, transformative deals delivered a negative return (-1.7%) compared to the market. It also found that the return increases as the company does more deals.

Another study, by The Boston Consulting Group, reported that serial acquirers conducted almost 40% of their deals at the beginning of an M&A wave (see Chapter 1), whereas the figure for single acquirers was 25% lower. It also found that deals conducted in the first stage of a merger wave delivered better returns to the acquirer.

Individual serial acquirers design their own processes based on their goals from the acquisition process and a solid understanding of the strategic planning which underpins those transactions. For example, one serial acquirer, 3M Corp., said that it prefers deals over $200 million in size, as smaller deals just do not have a large enough impact on the overall organization and its 40 divisions. According to its CFO, David Meline, who spoke in March 2013 at an industry conference organized by BoA Merrill Lynch, 3M plans to spend $1 billion to $2 billion annually on acquisitions. As its average division has revenues of between $750 million and $1 billion, he said they did not have a good experience with smaller deals, which he reported were around $50 million.

To maximize the benefits from this experience, M&A skills must be institutionalized in order to retain the knowledge within the company. This is often done through a special department (often called the “corporate development department,” but it can also be a part of a central strategy group or even the CEO's office). This is not just important for serial acquirers but for any firm that makes even occasional acquisitions, although it is certainly much more critical for firms that make frequent acquisitions. As David Harding, the co-head of management consulting firm Bain & Co.'s Global M&A practice is quoted as saying in the Financial News, “The gold standard of M&A is a repeatable model.” He went on to say, “Doing M&A half way may feel good, but doesn't generate results.”

Many companies lose the value of prior acquisitions by not even attempting to measure how successful the acquisitions have been. Studies consistently show that less than 50% of acquirers performed formal post-deal reviews or even include performance tracking in their integration. One study from KPMG in 2008 found that 52% of M&A “champions” (defined as companies that have achieved their deal synergies more than 75% of the time) always conduct a post-acquisition review, whereas only 38% of “non-champions” do.

If you don't know what to measure, how do you know if you've succeeded? In any merger, lessons need to be learned in order to make future deals more successful. Cost-reduction benefits are more often easier to achieve than revenue-enhancing benefits. Fewer companies track revenue-enhancing benefits rather than cost-reduction “benefits,” even though most pre-acquisition press releases emphasize the new business opportunities from the merger or acquisition. Little is done to determine whether deals result in new customers, better sales force efficiency or cross-selling, a positive effect on the product distribution channels, improved new product development, or other similar integration revenue-related benefits. The “cost” issues have greater focus, perhaps because of their ease of measurement but still many companies do not even monitor this rigorously. Headcount reductions seem to be the most common item tracked; items related to the systems supply chain, manufacturing processes, distribution, outsourcing, and R&D are less frequently tracked.

Post-Deal Review Team

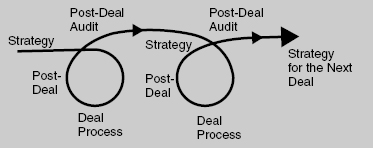

It is therefore important that the post-acquisition performance review be utilized as the final step in the M&A process although, in another sense, it is also the first step in the planning of the next deal (see Figure 11.1). To do this effectively, the major elements of a specific and focused post-acquisition review should be in the form of a formal audit, with a team chosen optimally from the original deal and post-deal integration teams, plus some people who are independent from the process and were not deeply involved with the merger planning and implementation. If advisors played a significant role in the deal, they should be included as well. All members of that team must be briefed on the strategic, financial, and organizational objectives of the deal, so that they can identify where the linkages were made or neglected.

This post-acquisition performance review must be the responsibility of the line managers, although they can certainly use the assistance of the corporate development or strategy department (if one exists), as well as internal audit and outside advisors, consultants, and auditors.

Post-Deal Review Timing

Adequate time must be allowed to conduct the review. The process of the post-deal audit should be in place at closing so that these reviews can take place roughly as follows:

- The first review point should take place within a month of deal closing. It should cover the pre-closing period of preparation plus the initial progress of the integration.

- A major review should be done at the end of the first three months or 100 days, which is typically the time when the organization takes a breather after the intensive initial integration period. As such, it may be the first time when true results appear in terms of customer reactions to the deal and employee satisfaction surveys.

Further reviews should take place, depending on the company and the type of deal, to include, at the very least, a larger review covering all aspects of the deal after one year. The KPMG survey noted above found that more than half of M&A champions always conduct a post-acquisition review within 12 months of the deal.

For some companies making frequent acquisitions, it may be more difficult to separate the results from different deals, so these may need to be looked at in aggregate. Under no circumstances should the impact of a subsequent deal be used as an excuse not to perform the post-deal audit.

What should Be Measured and Tracked

Pre-agreed performance benchmarks should include all aspects of the deal, not just financial or headcount numbers. There should be clear reporting on reasons for success and failure in each area being assessed.

The items to measure will naturally differ by company and deal, but there are some general areas that will be necessary in almost any deal. These include looking at shareholder return on investment and the more qualitative goals announced at the time of the deal.

The return on investment is not always easy to assess, because the acquisition may be rapidly and fully integrated into the buyer, making breaking out the deal benefits difficult. This is one reason why many firms break this area out into short- and long-term objectives. One of the most important quantitative measures to track is the achievement of synergies, including its cost. This is often a figure which is shared externally. Other accounting and financial metrics might include an increase in profit margins, cash flow, or top-line sales growth, or conversely a decrease in leverage.

In addition, the financial measures should be benchmarked against the forecasts for the company pre-deal and the financial expectations of the deal itself. If the acquirer is public, there will certainly be external stock market analysts who will have provided these forecasts. These can and should then be compared to the performance of the company post-acquisition. They will incorporate the additional value from the synergies derived from the combination of the two companies, as well as any other financial factors brought into the buyer from the deal. External analysts will certainly make these comparisions, but an internal assessment of the post-deal performance should also be conducted to determine the economic value added (known as EVA) of the deal. This EVA must be positive for the deal to be considered a financial success, and companies should strive to exceed the market forecasts.

In addition, there will be non-quantifiable benefits that will be almost impossible to include in the cost-benefit return analysis, thus making it essential to include a second category of measurement area. This will include the non-financial goals set out at the time of the announcement of the deal. Such qualitative items may include market share targets, retention or acquistion of particular clients, use of the newly acquired brand name or other intellectual property in other areas of the company, access to new geographic markets, culture change, protection of the supply chain, etc. What is critical is to make sure these are articulated at the start of the deal planning process so that they can be tracked later. Many will require special surveys, such as the monitoring of employees and clients.

Of course, recognizing that plans and goals need to be flexible and may change, the assessment measures are also subject to alteration, but great care should be taken to ascertain that the tracking is not changing because of a lack of success against the original goals.

Applied Learning

In using the results of the reviews, past experience will become the guide to the future. A number of possible mistakes can be made, however. There might be the tendency to view today as identical to the past, and thereby make inappropriate generalizations from the past to the present. Conversely, there is sometimes a tendency to say that today is very different so the lessons of the past do not and will not apply, leading to the belief that the new acquisition is unique in all aspects, when in fact many similarities exist. Experience should be used discriminately, but never ignored. This is a key lesson from military and business intelligence.

Acquirers must also be resilient in adapting their learning to the present. The easiest application of prior experience is clearly for firms making multiple acquisitions within the same industry horizontally or even vertically, but reviews should still take place when this is not the case. Acquirers with well-specified and codified integration processes should be able to have significantly improved accounting returns on assets and long-term shareholder returns. In the studies which we have conducted, this certainly appears to be the case.

Role of Advisors

For firms not large enough to have corporate development departments or which make acquisitions infrequently (in the order of less than two or three deals annually), close advisors can be used as a repository for much of the organizational learning. This needs to be done formally, as it is not a natural role for most advisors. Otherwise, they may change their coverage team, resulting in the loss of much specific company knowledge, which is detrimental because personalities and culture play such an important role in deal success. It may be best for the firm's auditors to fill this role, as they do not change as frequently as some other advisors. If they do maintain the organizational learning, it should not be done in the context of the formal accounting statement audits, but rather as a separate effort. There is, therefore, a critical role for advisors in the post-deal audit period, and that is in the assessment of the impact of the deal on both employees and clients. This needs to be done independently of management in order to provide clean results.

Perhaps the most important advisory function, and possibly the most neglected, is that of the critical friend. Nassim Taleb's book, The Black Swan, features a fictional character called “Brooklyn” or “Fat Tony.” Fat Tony's role is to challenge constantly the self-proclaimed experts' predictions with his particular brand of common sense. Taleb describes Fat Tony as follows, “Tony is remarkably gifted at getting unlisted phone numbers, first-class seats on airlines for no additional money, or your car in a garage that is officially full, either through connections or his forceful charm.” He is the guy you want on your team.

Taleb uses Fat Tony as a counterbalance to his Dr John (non-Brooklyn John) character, who is a nerd. In Taleb's world, a nerd is, “Someone who thinks entirely within the box.” So, Fat Tony is the counterpoint to the financial “experts” that Taleb encounters within the finance industry. Every deal needs a Fat Tony to cast an eye over it in order to point out the obvious to those too close and too attached to any particular deal. Naturally, recruiting such a character, either internally or externally, is a sensitive operation but one that pays huge dividends. Fat Tony always knows when to say no.

Conclusion

The ability to be a successful acquirer can and should be a competitive advantage for firms who do it well. This is best done by codifying the M&A experience to facilitate organizational learning. Business unit managers must be part of the process at all stages (although not to the degree that will totally distract them from running the business during the deal process and integration). Top management should focus on the high-level issues and decisions (that is, not fire fighting, problem solving, or refereeing). Such tasks can be left to the dedicated acquisition department (such as Corporate Development) who will shepherd the process. An effort should clearly be made to retain these key staff members, as much of the knowledge will be retained at the individual level despite the best attempts to put it in writing. As noted earlier, M&A is an art, not a science – and the best practitioners are artists in the field of M&A, not merely finance experts, legal advisors, or negotiation specialists.