CHAPTER 2

Business Intelligence

In the first edition of this book in 2007 we opened this chapter by illustrating why the intelligence function is so important. We used two contemporary cases – EMI's failure to anticipate drastic changes in its marketplace and the Hewlett-Packard (HP) boardroom spying/pretext scandal – both of which significantly impacted the M&A process. Well, welcome back Hewlett-Packard. In September 2011, HP closed the acquisition of a company called Autonomy for $11.1 billion. Just over twelve months later HP wrote down $8.8 billion, almost 80% of the purchase price. Whether there was deliberate disinformation (fraud) on the part of Autonomy (as claimed by HP, but denied by Autonomy), or lamentable pre-deal due diligence on the part of HP itself, or negligence on the part of the auditors (although this does not obviate the need for HP to have been in control of what they contracted to the auditors) will only be established over time in the courts. What is clear is that the acquisition was either a colossal intelligence failure that cost HP the best part of $9 billion or a strategic blunder of unimaginable incompetence by the CEO and the board.

Equally alarming, or perhaps even more so from an intelligence standpoint, was the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS)'s role in the purchase of ABN AMRO in 2007. Only an almost complete lack of competitor and environmental intelligence can adequately explain the catastrophic decisions made by RBS. Indeed, the success of Santander, one of the other two members of the consortium which acquired ABN AMRO, acts as a stark counterpoint to the failures of RBS. Throughout the entire acquisition process the RBS hierarchy, including the board, was acting as if virtually blind. It did not know of the pre-emptive Barclays bid; it did not know of the series of clandestine meetings held between John Varley (Barclays) and his Dutch counterpart, Rijkman Groenink; it failed to appreciate the size and phase of the credit bubble, despite being active in the US markets where the bubble burst first; and it failed to question the hubris-driven strategy of its CEO. All, and more, of the above could have been remedied by the use of a competent intelligence function. In business there is no such thing as a pleasant surprise; any surprise is worrying because it indicates weak intelligence systems. To quote Sun Tzu, from the Art of War, “it will not do to act without knowing the opponent's condition; and to know the opponent's condition is impossible without intelligence.”

What the HP and RBS stories teach us is that intelligence should be at the very heart of all corporate endeavors and generally is not. Most of the external sensory functions of RBS and HP were either not working or not registering at the policy level.

Again, Sun Tzu articulated the significance of the intelligence function:

To fail to know the conditions of opponents because of a reluctance to give rewards for intelligence is … uncharacteristic of a true leader [and] … uncharacteristic of a victorious chief. So what enables an intelligent [organization] and a wise … leadership to overcome others and achieve extraordinary accomplishments is foreknowledge … so only a brilliant ruler or a wise general who can use the highly intelligent for espionage is sure of great success.

In these statements, Sun Tzu highlights the error of not acknowledging the centrality of the intelligence function to an organization and the need to populate that function with the most intelligent among the personnel available.

The Intelligence Function

We have deliberately referred to the “intelligence function” rather than to “competitive intelligence,” “corporate intelligence,” or “business intelligence” because there are no generally accepted definitions of those terms. Looking solely at the “function” enables organizations to identify whether that function is being carried out effectively or, indeed, even exists, irrespective of what their organizational charts and departmental titles might suggest.

In what might seem a contradiction, we suggest that a systems theorist might best describe the intelligence function. Stafford Beer, in his book Brain of the Firm (Wiley, 1972) prioritizes what he refers to as “System Four,” the “intelligence” system. In Beer's Viable Systems Model (VSM), System Four is the function responsible for all things “external and future.” The other functions are responsible, from the most senior down, for “policy” (System Five), “monitoring” (System Three), “coordination” (System Two), and “operations” (System One). So, whereas System Three is concerned with “internal and present,” System Four (“intelligence”) is only concerned with “external and future.” Additionally, and this is where Beer's view of the intelligence function differs from most, he sees that function as not only responsible for information incoming from the environment but also for projecting information into the environment. So, for Beer, marketing, public relations, and advertising would be part of the intelligence function. It is also our view that such a function is an integral element of the M&A process and should be organized as such.

For anyone in the government or military, of course, this is not unusual. In those organizations, intelligence has always had the dual roles of collecting and analyzing as well as pushing information into the environment, although the latter is often confused with disinformation. Incidentally, disinformation is also important in M&A and experienced practitioners of M&A are expert users of disinformation, although it will often be referred to only in the context of “signaling” the market about intentions. Deceiving potential targets and other players in the deal is an essential skill, although this should clearly be done within the parameters of accepted business ethics and in following the appropriate laws and regulations, of which there are many, governing public M&A deals. Of course, organizations should be conscious of, and prepare defenses against, unscrupulous tactics in this as in any other business activity.

For business, however, the idea of a wholly coordinated and integrated intelligence function is not generally accepted – or at least in modern business it appears not to be. There are, of course, notable exceptions. In the big pharmaceutical sector, for example, most companies have well established intelligence functions.

Ironically, in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, it was considered essential. The East India Company, for example, employed Richard Hakluyt who might be considered the father of economic intelligence. Hakluyt was appointed, in 1602, “to set down in writing a note of the principal places in the East Indies where trade is to be had.” It was an obvious appointment because Hakluyt had already published The Principal Navigations, Voyages and Discoveries of the English Nation, a tome which consisted of over 500 reports collated from other reports delivered by the complete gamut of European travelers, from explorers to pirates and colonists. These reports provided data on navigation, geography, resources, politics, and economics from every corner of the known world.

Business Intelligence Industry

Of course, in the modern era, such intelligence activities are largely outsourced, usually on an ad hoc basis. Indeed, there is a modern company named after Hakluyt, set up by former MI6 operatives, which claims its primary activities are to “promote commerce by the provision, supervision, and facilitation of business activities engaged in the research and supply of information for the use of commerce, trade, and industry in the UK and elsewhere.” The Financial Times in 1995 described it as a “body established to give British companies the inside information they need when contemplating big ventures in foreign countries.” If that sounds a bit like traditional Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) old boy networking in foreign lands, it is because that is precisely its nature. Remember the FCO from the previous chapter was itself the product of a series of mergers.

However, while the business intelligence industry might have started as an adjunct to the FCO in the UK, there are now more and more niche outfits providing a more professional approach to the intelligence function. The knowledge processing outsourcing (KPO) element of the industry generated around £200 million in revenues globally in 2006, which represented a 59% increase on 2005. It is estimated that the figure will reach £3.5 billion by 2015. KPO deals primarily with the electronic gathering and dissemination of knowledge for the full range of research needs of organizations.

The other elements of the intelligence industry belong to the big players such as Kroll, FTI Consulting, and K2 Intelligence. These companies will deal with demands for due diligence that go beyond simply auditing the books or reviewing material provided by the target company. They will investigate the provenance of the resources held by companies, interview ex-employees of target firms, check out potential breaches of the law such as the US's Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and the UK's Bribery Act, and generally provide the deep intelligence necessary to maintain corporate security and reputation. Most importantly, they search for information in advance of a deal that might otherwise prove to be a negative surprise post announcement or post closing.

The industry is also beginning to converge, with the big accountancy firms moving intelligence functions in-house, some of the big intel firms trying to move in the opposite direction into accountancy, and the old-style security companies such as Securitas attempting to access a slice of the investigative market. The other major area of intelligence convergence is the cyber security function which none of the players can risk ignoring, especially with the accusations at national level being thrown around and discussed widely in the press. Even US President Barack Obama and Chinese leader Xi Jinping have traded accusations with each other of cyber-spying, and the Edward Snowden revelations in 2013 showed the US government to be spying even on the leaders of its traditional allies, such as Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany, among others.

Whether traditional or modern, the intelligence function remains the same – to be the eyes and ears of the organization, to gather and, more importantly, analyze information that provides a competitive advantage. Of course, examples of failures to engage are numerous. Notwithstanding the classic and well-documented cases, such as retailer Marks & Spencer missing the personal credit card explosion (and indeed ultimately selling its credit card business to HSBC in the middle of a takeover attempt), and IBM initially missing the personal computer market, there are others that make the case for external engagement just as powerfully. There are also the failures of the big US auto companies to see “green-ness” as a business opportunity, record companies to see the internet as a channel for piracy or as a larger channel for the distribution of music, and internet gambling companies to see that the US Congress would actually legislate against its activities. Incidentally, those same gambling companies did react well by opening up new markets and have been actively planning and lobbying (an intelligence function) for the repeal of that legislation.

Why, then, does it appear so difficult for organizations to analyze and interrogate both the internal and external environments in which they operate? First, as most observers agree, there is a perception of greater complexity in the modern business environment. Getting to the other side of that complexity clearly involves greater knowledge of the environment but also greater knowledge of how to deal with complexity. Again, it is worth returning to the middle of the last century for advice. This time to the writings of Ross Ashby, who even had his own “law” – Ashby's Law of Requisite Variety. The essence of the law is captured in Ashby's contention that “only variety absorbs variety.” Substitute the mid-20th century use of the term “variety” with today's “complexity,” and you will better understand his “law.” What it means is that there should be a balance between environmental complexity and the complexity of the organization seeking to control that environment. This can be done either by expanding (amplifying) or contracting (attenuating) the complexity in one or more of the parts. Justin King, CEO of the large UK food retailer Sainsbury's, put it in 21st century language when he said, “Strategic advantage is still there. In a more complex environment, equally complex strategic solutions are necessary.”

GE and Microsoft, for example, can be characterized as organizations that expand their complexity to meet the complexity of the environment. They acquire and/or grow the diversity of their organizations. This requires extreme sensitivity to environmental dynamism. The acquisitive gazes of the traditional media companies at newer media outlets such as the internet and mobile phones are clear examples. They need such a foothold to enable their content to remain king. They need to increase the “variety” of their own organizations. The telephone company BT's acquisition, through BT Vision, of the TV rights to a variety of sporting content is another example.

How they do that is the stuff of strategy, of course. That is why when a social networking company such as Friends Reunited came on the market in 2006, a variety of content specialists such as the newspaper groups NewsCorp, Trinity Mirror, and the Daily Mail plus ITV (a television channel) and BT (a telephone company) immediately began to hover, despite indications in the market that consumers had already begun the move to Facebook and MySpace. Similarly, Virgin needed NTL (a cable company) to get into television, NTL similarly needed Virgin's brand and mobile phone capabilities, and suddenly the group was able to provide customers with the quadruple offer (pay TV, mobile phone, traditional phone, and internet). So, BSkyB (satellite television) buys Easynet (a broadband internet provider) and ITV ultimately buys Friends Reunited. All such deals, or their equivalents today in telecommunication or other industries, are attempts to amplify complexity in the organization. Interestingly, BSkyB's acquisition of ITV shares was aimed at restricting NTL/Virgin's complexity. Conversely, other organizations are offloading businesses in order to concentrate on what they perceive to be “core” businesses. These businesses are effectively contracting the environment with which they intend to engage. According to Ashby, either solution can work; what cannot work is an imbalance in variety.

The second reason why organizations fail to engage with this environment is that they do not believe it is necessary. They become complacent. They believe that their approach has worked, is working, and will, therefore, continue to work. They even fail to observe the environment, much less respond to it. Again, the hubris-driven ignorance of RBS stands as an example.

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, organizations simply fail to give sufficient thought and resources to intelligence as a function. Remember the advice from Sun Tzu, quoted earlier in this chapter, about the importance of “foreknowledge.” He also pointed out that unwise leaders often choose to limit the effectiveness of the intelligence function by according it too little value and consequently too few resources because of the “reluctance to give rewards for intelligence.”

What's Out There?

Having a highly effective intelligence function would enable even those organizations that do observe the environment to increase their chances of survival and prosperity, whether through a period of organic growth, acquisition, or post-deal integration. They could more accurately detect external threats, which include the obvious market concerns, such as how competitors are behaving, but could be equally concerned with aggressive competitors, criminals, and environmental changes. Corporate fraud, identity theft, reputational damage, computer spying, and the vulnerability of online commerce, for example, are all issues that must be addressed. In 1999, cyber-crime losses in the US ran at somewhere near $250 million; in 2015, it is expected to be closer to $5 billion. Attempted ransom attacks on companies such as Google and eBay, where the essence of the business is the technology, are obvious targets although, to be fair, companies that rely primarily on their technology mostly take adequate precautions.

However, evidence suggests that many other businesses are still complacent about cyber-crime, particularly such dangers as the theft of corporate data and consumer data theft. The open nature of the internet and the rapid turnover of innovative technology mean that new channels are constantly being opened up for the cyber-criminal. It is estimated that a majority of web servers are still vulnerable to hacking attacks. Such threats are not two, three, four years old and now under control; they are current and ongoing. The good news, according to a source at the British National Hi-Tech Crime Unit (now the National Cyber Crime Unit), is that avoiding such traps is relatively easy – “don't take the bait.” The bad news is that a sufficient number of companies and individuals do take the bait. Boiler room and Ponzi scams are increasing despite the greater knowledge of their existence. And it is not the fault of the technology.

The reason criminals thrive in cyberspace is not the technology, but the people. Most of us are either inexperienced with modern technology or just plain ignorant. We do not have sufficient knowledge to sense vulnerability. John Naughton of The Observer once told a great, possibly apocryphal, story which makes the point precisely. According to Naughton, he supervised a project team at a nuclear installation. Apparently, the guys there ran a competition to see who could get into the site with the most ridiculous security pass. The winner was waved through using a box of John West sardines. Of course, this may just be a story but it is one with which we can all identify.

Irrespective of the quality of technological security, human beings will mess up; they will use predictable passwords, they will stick those passwords in open view, they will talk in public places; human beings will be unaware of the dangers of “drive-by” hacking – that is hacking into laptops and smartphones using wireless connections in public places where people log into wifi systems, such as Starbucks.

Added to simple human inadequacy is criminal activity, another human failure. In early 2005, for example, a British immigrant in the US was jailed for 14 years for his part in a $100 million identity theft scam. Philip Cummings did not use “spyware” or “phishing,” instead he simply stole the information as it crossed his desk as part of his work on the helpdesk of the US company Teledata Communications. He downloaded the data onto a laptop and passed that laptop to a criminal gang. The gang, in turn, drained the accounts of as many as 30 000 US citizens. Recent Wikileaks incidents only confirm the human element of intelligence failures.

The point is, no matter how sophisticated hackers are, they need access like any other thief; the easiest way to gain access is for somebody on the inside to open the door. USB sticks and other mobile data storage devices make data theft relatively quick and easy once there is somebody inside the organization. No anti-spyware or anti-virus software, or firewall, can protect against the insider. And don't think that insiders are passive until activated by nasty outsiders. They can be planted in an organization. As Callum McCarthy, the former chairman of the former UK Financial Services Authority, has stated, “There is increasing evidence that organized criminal groups are placing their own people in financial services firms so that they can increase their knowledge of firms' systems and controls, and thus circumvent them to commit their frauds.”

Not only can such activities cause enormous commercial damage, they can also cause major reputational damage. While we have concentrated here on malicious external threats, the same intelligence function would also be responsible for scanning the environment for generic market threats and M&A opportunities. Environmental scanning will be dealt with in more detail later in the chapter. It is clear that engaging with both the internal and external environments is not a benign, nice-to-do activity; it goes to the very heart of the survival of the organization and it is essential that the entire workforce understands the significance of the activities.

How Do We Project the Company's Message into the Environment?

In reality, the above explanation about the intelligence function should be common sense, notwithstanding the fact that few organizations take it as seriously as they should. However, as noted earlier, what the Viable System Model also promotes is the idea that the intelligence function should not only be responsible for data incoming from the environment, but also have responsibility for projecting information into the environment. At its simplest, this entails sending messages about the organization's identity (brand), intentions (strategy), and activities (products and services). It can, of course, also include disinformation, spinning, and black ops.

Looking at the brand issue, for example, indicates why Beer believed the projection and collection of knowledge from and to the environment should be integrated. The way in which “brand” is projected into the environment is as important as the way it is protected from the environment. As demonstrated earlier, reputation can be easily damaged and must be defended. A damaged reputation can cut millions from a bid price and seriously weaken bargaining positions. However, that protection must start with the manner in which the messages are sent. This is what differentiates VSM. Using the VSM approach entails a symbiotic relationship between protection and projection. The one informs the other. Thus, analysis of the environment (traditional research) can identify opportunities for marketing, sales, and negotiators. It also enables the organization to build trust by activities such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sponsorship, as well as other previously disconnected activities. What could be more similar to a traditional intelligence activity, for example, than viral marketing – it's a classic propaganda exercise.

The beauty of this integrated approach is that it co-locates these activities under a single function, which naturally generates sharing and eliminates siloism. This is, of course, the very claim made by business intelligence (BI) systems vendors. In the first edition of this book, corporate performance management (CPM) was the latest of such “products.” As Oracle pitched it on their website in May 2005:

CPM aims to underpin corporate performance and governance by delivering timely, accurate, relevant, accessible information to every desktop. It gives a company a single, x-ray view through the entire organization. …

Oracle's website today advises that Oracle Business Analytics (its business intelligence component) can:

Evolve your IT into a role of business enabler by standardizing on a single, scalable business intelligence (BI) platform that connects people with information – anytime, on any device – and accelerates decision making. Oracle BI tools and technology provide a broad set of capabilities for reporting, analysis, modeling, forecasting and it is the only solution that makes BI actionable by providing business users the ability to initiate actions directly from their dashboards.

Incidentally, CPM has now morphed into EPM (Enterprise Performance Management).

No problem, then. Performance and governance can be dealt with by an expensive IT system. And, of course, this will be the one that actually works. The fact that, by most estimates, as much as 80% of CRM (Client Relationship Management), BI, or CPM/EPM capacity is never used is too easily ignored. The answer to the question of how best to engage with the external environment may not be to install a costly BI product, but to create an organizational intelligence system, a System Four. But how?

Review

The first thing to do is initiate a review of the components of the company's external interaction. This does not need to be a six-month formal review carried out by a consultant and costing a fortune. A day's facilitated discussion with the senior management team, fully engaged (which probably means off-site), should suffice. The objective would be to identify any gaps in the external provision, any disconnections between the components. If, however, the company is similar to one of the over 50% of Fortune 500 companies which has an intelligence input into the development of their strategies, then the review will deal with the existing effectiveness of that input. As stated, the review process need not be complicated or expensive, but it will be resource intensive and that resource will be the brainpower and thinking time of the senior management team, and not just for the discussion day.

Prior to the day, divisional heads must access the latent knowledge stored by and in their staff. Here, we recommend a revolutionary technique – ask them and listen to the answers. Not electronically, but in person. And make the questions simple: “What extra information would make a big difference to your numbers if we were able to provide it?” “Where do you think we might find it?” “What's stopping us getting it?” Collate the results of that process and the resultant document becomes the foundation of the brainstorming. When Allan Leighton joined the Royal Mail as the new Non-Executive Chairman in 2002, he did not visit his office for at least a week; he was too busy out asking questions of the workforce. By 2013, changes that he initiated at the Royal Mail made it ready for sale, having been in profit for a significant period. As we now know, it was sold and immediately doubled its initial share price. The same personal questioning approach applies to the due diligence process in an acquisition, as we will discuss in later chapters.

The other early issue the review must address is that of outsourcing. Is the intelligence function compatible with outsourcing? The answer is that like most functions it can be outsourced. In fact, the fastest growing outsourcing business is what is referred to as KPO (knowledge process outsourcing). India has, again, led the way. A variety of small companies with, on average, about 30 employees have sprung up to satisfy the intelligence needs of the large corporates. These companies have bought access to virtually every database on earth and, with their teams of highly educated graduates, they can respond to what is referred to as activated or targeted intelligence requests almost immediately.

Structure

Having identified the gaps or inefficiencies in the company's established intelligence system, remedies must be implemented. For example, if the intelligence system is viewed as the conduit without which other systems cannot succeed, then consider co-locating the marketing, IT, and R&D under the direction of a single head, the chief intelligence officer (CIO) perhaps.

Of course, structural change is not enough on its own. There must also be a cultural shift. Most importantly, there need to be transparent rewards for sharing information. An organizational check in virtually any company will almost certainly find that it actually rewards hoarding information. For example, imagine getting the sales teams together and asking them to share client information fully. Now imagine the response. Precisely how to change the culture from hoarding to sharing will be particular to each organizational situation, but this is an area where it is clearly worth expending serious thinking time. Without changing this cultural mindset and engendering a thirst for intelligence, developing the intelligence products is pointless.

The Products

It may be that internally advertising the product range can actually stimulate recognition of the value of those products and change the culture. Essentially, there are ten products that a mature intelligence function can provide:

- Immediate intelligence

- Continuing intelligence

- Technical intelligence

- Analytical intelligence

- Absorptive capacity

- Environmental scanning

- Scenario planning

- Internal intelligence consulting

- Activated intelligence

- Counter-intelligence

Immediate Intelligence

This is intended to provide end-users with intelligence within a 24-hour time frame. It is usually collected from open sources and passed to the user without any significant, or in some cases no, analysis. It is either requested on an “alert” basis or is part of a “daily briefing” delivered via e-mail, intranet, social media or even hard copy. Given that this product is resource intensive, it may be sensible to outsource to one of the fast-growing KPO firms mentioned earlier in the chapter.

Ashish Gupta, the COO of one of them, Evalueserve, describes the service they provide as “research on tap.” KPO companies employ knowledge workers who become the outsourced intelligence function for their clients, be they banks or consumer product companies, for example. KPO can provide the analysis upon which early decisions concerning M&A are based when all the data sources are external to the target as no contract has yet been made which would allow internal due diligence to start. The labor-intensive report compilation can also be outsourced, which would free up the expensive time of London- and NY-based investment bankers to concentrate on other value-added activities, including the face-to-face meetings which generate deal flow. It would also have the added benefit of physically separating the research and trading functions at the heart of many recent financial scandals.

The National Association of Software Services Companies (NASSCOM), the Indian trade association, estimates that the KPO industry will be worth $17 billion by 2015; that is a 15-fold increase since 2008. If true, it means that your competitors will probably be using it. Although the KPO option has been included in this section on immediate intel, it should be obvious that it can also be used for most of the intelligence products that follow.

Continuing Intelligence

In contrast to the “quick and dirty” intelligence provided by the “immediate” product, the “continuing” product is rigorously researched, analyzed, and documented. Delivering this product entails continuous monitoring of the competitive environment – competitors, trends, and irregularities – in fact, anything that can add competitive advantage. Continuing intelligence is rarely actively disseminated; rather it becomes an element of the intelligence database from which decision makers can draw information. Of course, it is necessary for the holders of the database to advertise its value and availability to the internal market. This is a powerful reason for fully integrating the intelligence function. By so doing, the users can influence the content of the database in an iterative process. Thus, the managers driving an M&A deal which originates anywhere in the organization should therefore know of the existence of the corporate intelligent function and be experienced, if not even frequent, users of the data that the intelligence function collects and analyses. This is a true competitive edge in the vicious world of M&A where every advantage needs to be taken.

Technical Intelligence

Traditionally, this has been an area of intelligence seen as competitively neutral. The idea was to maintain technological competitiveness and to manage R&D and new product development projects effectively. However, the environment has changed because the modern consumer is much more sophisticated and now views product content in technological terms. Technology is not simply the way in which corporations adapt to market demands; rather it is a significant product attribute. It is not simply having a car that functions which adds competitive advantage, but the technology inside the car which differentiates it.

Consequently, the way in which organizations pick up technology signals from the environment is as crucial as their technological prowess. One group of researchers (Schatzel, Iles, and Kiyek) suggested that a “firm's capability to receive technological demand signals from buyers, its technology demand receptivity (TDR), influences its response to those signals and, thus, influences R&D, as well as new product development efforts and, consequently, its overall industry competitiveness.” In the past, this has been done by keeping a close eye on technologies emerging from research institutes or universities; sponsoring chairs, for example, enabled companies to get early sight of developments.

The future will require that even research can no longer be siloed if organizations are to remain competitive. Depth of knowledge will be required across industries which are liable to converge and therefore drive further mergers and acquisitions. For example, we have already seen the convergence of TV, the internet, and the gambling industry. Online gambling has converged with TV sporting events and, indeed, many sporting organizations are even sponsored or endorsed by gambling businesses. Organizations which can imagine convergence and monitor the technology to enable it will be the ones to benefit first and possibly most. In the gambling industry this will be in spite of the legal restrictions imposed by the US at both the state and national level. In fact, these restrictions have made creativity even more important. Interestingly, various US states are lifting the internet gambling restrictions and it is only a matter of time before that becomes even more widespread, thus opening the way to even further innovative mergers.

Analytical Intelligence

In a sense, the early warning receptivity necessary for technological competitiveness precisely mirrors one part of the analytical product so essential to an organization's survival. The first part of the analytical process is to provide advance warning of emerging opportunities and/or threats. In its simplest form, this might be “intelligence alerts.” However, such an interpretation of an early warning system fails to understand the true value of the product.

What actually needs to happen is two-fold; first, the intelligence analysts must develop a comprehensive list of potential indicators and a capacity for doing so effectively to the second phase, which consists of scanning the environment. In that way, as the environmental signals begin to arrive they can be immediately checked against the dashboard of indicators previously developed. Each M&A deal will have its own dashboard, designed and developed specifically for that transaction.

Absorptive Capacity

Organizations need to develop what has become known as “absorptive capacity.” Cohen and Leventhal, who originated the concept, argue that “the ability of a firm to recognize the value of new, external information, assimilate it, and apply it to commercial ends is critical to its innovative capabilities.” It is, therefore, essential to understand the sources of an organization's absorptive capacity. These range from the traditional R&D function to the diversity of expertise within an organization. The research shows a clear and direct correlation between the organization's prior related knowledge and its ability to absorb new externally generated knowledge. Thus a failure to invest in developing diversity of knowledge may actually impede future development in a particular area. The conclusion must be that what we, in this book, refer to as the intelligence function and business innovation are completely interdependent and symbiotic.

If that is the case, then the manner in which the holders of diverse knowledge interact internally becomes of vital concern to the business when trying to absorb external information. Clearly, such recognition reinforces the anti-silo imperative that we have argued is needed for technological innovation. Organizations must, therefore, put in place procedures to enhance “absorptive capacity.” Such procedures could include communication and knowledge-sharing routines between departments and partners. The message must be that more thought should be given to location and accommodation issues, such as open-plan and clustering. It is also likely that the absorptive capacity of a company may be diminished during the course of an M&A deal as employees and managers alike are distracted by the seemingly more urgent activities of combining the two companies.

Environmental Scanning

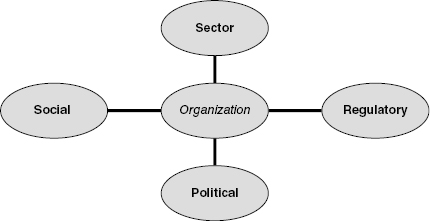

However, to leverage fully its absorptive capacity, an organization must also be actively seeking greater knowledge. This is where environmental scanning is so important. Although some individuals may do this instinctively, organizations must do it consciously. According to a survey conducted by the Fuld-Gilad-Herring Academy of Competitive Intelligence, more than 65% of 140 corporate strategists interviewed admitted to being surprised by as many as three high-impact competitive events over a five-year period. Such surprises can only be avoided by continuous scanning of the environment. The significant environment for any organization consists of the four subsets, indicated in Figure 2.1, which continually impact that organization:

- Sector: Naturally, sector-specific information is central to competitive intelligence requirements. Data in this sphere should include competitor analysis, technological developments, customer activity, supplier details, and potential targets or attackers.

- Regulatory: Regulatory issues such as financial reporting rules or foreign ownership laws can have huge commercial ramifications; this is particularly true in the M&A arena which, especially for publicly-listed companies, is a highly regulated activity as will be discussed in several places later in this book. Rupert Murdoch's entry into the US to expand his global media empire, for example, was fraught with regulatory obstacles, some of which were overcome with US citizenship. Internet gambling is another obvious example, mentioned earlier, of an industry desperate for regulatory intelligence as is the burgeoning global for-profit higher education sector.

- Political: Knowledge of political factors, including local, regional, and national economic climates, should be a prerequisite of the decision making process. The attempt by the United Arab Emirates-owned P&O to acquire US ports in early 2006 was ultimately thwarted by political reaction. An earlier and more sensitive intelligence assessment may have contributed to the development of a different entry strategy that would have delivered a more favorable result. We will return to that case later in this chapter and the next.

- Social: Similarly, social concerns, such as shifts in ethnic, gender, age, or national characteristics, could massively affect a company's ability to operate and prosper in a particular environment. In Peripheral Vision, an interesting book by Day and Schoemaker, the authors developed what they refer to as a “strategic eye exam.” This is “a diagnostic tool for evaluating and sharpening companies' peripheral vision.” The exam tests an organization's strategy, the complexity and volatility of its environment, its leadership orientation, awareness of its own knowledge management systems, and its structures and incentives. An awareness of an organization's peripheral capability, the authors argue, allows companies to scan the environment more effectively for such surprises as that which befell P&O's US acquisition strategy. Perhaps the most important advice to emerge from their book is the simple device of concentrating on “open” questioning. Answering a question such as “What will the world look like in 2030?” is of an entirely different order to a quantitative question such as “What are our sales figures for Q1?” Both have their place but a predominance of either can be dangerous.

Scenario Planning

Having scanned the environment and separated the signals from the noise, how does the analytical product then add the most value in mergers and acquisitions? The answer is by scenario planning. The first thing to realize is that the process of scenario planning is the consequence of a culture obsessed by the future – its risks and opportunities.

Another company famed for its extensive usage of scenario planning is Shell. Using their own jargon, Shell's scenarios team is tasked to “help charter routes across three interrelated levels”:

- Long-term trends, uncertainties, and forces

- Specific features of key regions

- The turbulence of market level factors.

To get a feel for the Shell approach go to www.shell.com/scenarios. Whether a scenario planning function is structured as a Samsung hothouse or a highly centralized Shell-like group, the point is to monitor simultaneously the past, present, and future. In all instances, in addition to the expected, it is essential to attempt to imagine the unimaginable. From those imaginings, scenarios must be built such that when a “new” scenario presents itself, it is, at the very least, recognizable.

If a company cannot afford the infrastructure to deliver such comprehensive reports as part of their acquisition planning, then use alternative means. The US National Intelligence Council, for example, provides free scenario projections on their www.dni.gov/nic site. Although generic in nature, this site is a good jumping-off point at the start of the merger planning process.

Also, because humans find it difficult to calculate probability rationally, a company's intelligence function can use the power of the bookmaker. Daymon Runyon, famous American author from the first half of the 20th century, paraphrasing Ecclesiastes, said that “The race might not be to the swift, nor the battle to the strong but that's where the smart money goes.” By using trading (e.g. www.intrade.com) and/or spread-betting (e.g. www.cantorcapital.com) sites, a company can see how the world really views the likelihood of specific events and, significantly, how their own company is viewed by the market. In 2003, an insensitive but smart analyst at DARPA (the Pentagon's Defense Advance Research Projects Agency) proposed setting up a speculative futures market on terrorist attacks. Notwithstanding the obvious temptation for real terrorists, the idea was sound. Getting people to bet real money on future events focuses the thinking of those people and saves the inordinate costs of expensive computer models. There really is wisdom in crowds and this perhaps also explains some of the activities of arbitrageurs (discussed later in Chapter 6), and the fact that even the market regulators admit to unexplained activity in the share trading of companies about to announce an M&A deal (which will be discussed further in the next chapter).

Companies could actually create their own internal speculative markets to leverage the knowledge contained within the organization. By allowing employees to bet on specific questions (using company money for real returns), an efficient market for ideas can be created. More real, more relevant, and more fun than a “suggestions box!” Apparently, the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly has used this approach to predict the success of drug research with remarkable accuracy, and there is no reason to doubt its applicability to the M&A market as well.

Internal Intelligence Consulting

Many companies fail to utilize their intelligence analysts as fully as they might. Embedding analysts within internal M&A teams allows the analyst to provide targeted and timely intelligence to the group. Another internal function that the intelligence community can provide is the establishment of educational seminars to a variety of users to provide product and service visibility, and to promote the value of the intelligence function. Employees are then better prepared for the intense period of an M&A deal when “education” may seem a luxury.

Activated Intelligence

If the internal community recognizes the value of intelligence products, it will naturally generate “activated” requests. These are requests generated by both formal and informal observation of the environment. A casual reference in the business press or an overheard remark can require some speedy intelligence.

Activated intelligence only appears at the request of a client and is tailored to that client's needs. The most obvious situation during which such intelligence is needed is leading up to or during an M&A deal. In such situations, the role of the intelligence function is to provide speedy, targeted information. It is essential that an intelligence expert therefore be embedded in any M&A team. After the closing of the M&A deal, the intelligence community will review, analyze, and debrief the relevant teams. The consequent reports and any other documentation will form part of the organizational knowledge base for future M&A deals, as will be discussed towards the end of this book.

Counter-Intelligence

The final product, if it can be so termed, is counter-intelligence. This function covers activities undertaken to protect the company. It is as important to secure your own proprietary information as it is to find out about others. The vulnerability of organizations, both human- and systems-based, has been discussed elsewhere and it is the role of counter-intelligence to minimize any damage done by competitors or maliciously driven intrusions.

Damage limitation may seem a low-level ambition but it is realistic. Breaches of security will happen and the smart intelligence worker will attempt to predict those breaches and respond immediately when that prediction occurs. Knowledge of the inevitability of failure must be integrated into strategic decision making at the most senior level. In an M&A deal, for example, it is prudent to assume that confidential discussions will be leaked to the target or the press. This doesn't mean one expects this to happen – nor should it mean that the company should be less vigilant in trying to prevent it from happening – but it does mean that a plan should be in place in case it does happen.

Technology can also be used illegitimately to spy, bug, or invade. It is not unusual now for the senior officers of major corporations to have their offices, homes, and vehicles regularly swept for bugs.

How Should the Intelligence Products Be Delivered?

Having educated the M&A team and, hopefully, the entire organization to the range of products available, the individuals using that business intelligence will also need to be satisfied as to how those products are manufactured and delivered. Although the analysts deliver the products, they rely on others for the production of the raw material – information. This is the job of the intelligence collector. The collectors' work is done either technologically or by human intervention. Technology can come in any form. Technologically enhanced intelligence gathering can be simple CRM, RFID (radio frequency identity) tagging, CPM, data mining, or video mining. Ideally, for the organization, it is a combination of these systems which will provide an almost complete breakdown of an individual's or company's behavior.

Intelligence gathering by human intervention also has the capacity for illegitimacy. Falsely representing oneself (as in the scandal of Hewlett-Packard's “pretexting” to trace boardroom leaks), phantom interviews, and intrusive networking are all used to gain information. Ironically, however, most information is fairly easy to come by without subterfuge, although the really important information will definitely require digging and may require cash.

Conclusion

Knowing that an understanding and awareness of the external and future is an essential component of any M&A strategy is one thing; organizing, structuring, and convincing the rest of the company to see intelligence as a core function is something else again. This is, perhaps, one of the most important cultural shifts that an organization needs to make. Easy steps, such as providing an intelligence hotline or intelligence website, asking for help around the organization, creating a virtual intelligence community, and interacting positively with the sales force, can all begin to adjust the climate; changing the culture takes much longer but must start with these simple behavioral alterations. By failing to coordinate and prioritize the intelligence function, companies increase the risk of failure in any endeavor but perhaps most significantly in the M&A game where so much is at risk in the firm, as mentioned earlier. Risk assessments rarely recognize that the biggest risk to an organization is the failure to harness the intellectual potential which exists within the company, to look out and forward, and to apply it in all corporate endeavors, including the acquisition or merger process.