CHAPTER 8

Valuation, Pricing, and Financing

Proper valuation is critical to the success of any merger or acquisition. Without it, a company might pay too much for the target or the target might accept a price that is lower than the value shareholders should accept. When two companies are deliberately combined as one through a process as significant as a merger or an acquisition, it is not surprising that those shareholders as well as the employees, clients, and others expect that there will be value generated from the deal's strategic and business objectives.

Each company and deal is different and there is no single best way to value a company – no “one size fits all.” In many ways, valuation in M&A is an art and not a science. Proper valuation comes with experience. Each valuation includes myriad assumptions which need to be made and small changes in any of these assumptions can have a large impact on the valuation.

Value versus Price

At the outset, in any discussion about the financials related to an M&A deal, the differences between valuation and price need to be highlighted:

- Value relates to the amount of money that the target company is worth to the bidder, typically taking into account the initial price paid plus any additional expenses (the costs of the deal as well as post-deal integration costs) less any synergies that will accrue to the new parent when the two companies are combined. This typically should be calculated taking into account the time value of money. This is not to say that the value is composed exclusively of financial data, as there will always be non-financial factors that are considered, as discussed in the first chapter. Taking all of this into account, the buyer should be unwilling to pay more for a company than it has calculated it is worth. From the target's perspective, it will have a valuation for the company on a standalone basis which it believes fairly represents the value today of the future earnings of the company together with the net current assets, both tangible and intangible.

- Price is the figure at which a deal can be transacted. It may relate to value (and certainly the buyer should not pay more than it has calculated the value to be; nor should the target company be willing to sell the company for less than it feels it is worth). It is, however, the market price at which a willing buyer and a willing seller would agree, neither compelled to sell (that is, not in a situation where, for example, a regulator has required the company to be sold or when the target company is in insolvency and it must be sold in order for the business to survive). Value may drive whether the seller or buyer can agree a price, but the price agreed is an independent calculation typically based on similar recent deals.

Note that the price and value are both company- and deal-specific. Different buyers will value a target company differently as each will have a unique plan for the post-deal company and differing abilities to achieve financial synergies, for example. Similarly with sellers, as the price at which one company would be willing to sell will almost definitely be different (and calculated differently) than for any other company. This implies that there is no single value or single price for a company and any calculation is dependent on the buyer and what it plans to do with the target.

Control Premiums

One of the most important factors to consider in determining the price of an acquisition is the necessity to include a control premium. In order to take a company over – to buy more than 50% of the company – the current owners need to be “bribed” to sell their shares to the new owner. This control premium averages at approximately 20–40% over the undisturbed share price for publicly-listed companies, and has remained remarkably consistent within this range over the past several merger waves.

What drives a higher premium? Analyses have shown that the price will be higher if there are multiple bidders for the company (thus creating an auction effect), for cash bids (as opposed to share or partial cash bids), and when the target company has a particularly strong bargaining position (such as a controlling shareholder or defensive tools at hand: for example, a poison pill, as discussed in Chapter 6).

Normally, day-to-day share prices quoted on the stock exchange do not include a control premium as most trades are minority stakes. The control premium will differ by industry, market, and company, and is best determined by looking at recent previous acquisition transactions in similar deals. Some industries may experience periods when the industry is “in play” as one or a number of acquisitions and mergers are taking place. In this case, part or the entire control premium may be reflected in the current stock price as there is an expectation that the independent companies in the industry will also be acquired at a premium.

Alternative Methods of Pricing and Valuation

Significant time pressures force short cuts to be made, especially in hostile, unsolicited bids. Traditional corporate finance and private equity methods of valuation are not typically applicable on their own, as M&A strategic valuation must include the impact of combining two companies.

For example, when pricing a company for an initial public offering (IPO), there is usually a discount applied to the ultimate price in order to give the initial investors some upside potential in share price and to improve market liquidity by making sure that the volume of shares that will trade is adequate. While an M&A deal is typically transacted at the premium to market price as noted above, most IPOs have a target discount of 5–15% once the issuers have determined what the appropriate price for the new shares is. The acquisition stock prices for a privately held target may therefore be as much as 50% higher than the price that could be achieved if the company were taken public in an IPO.

This is particularly important to start-up companies and to private equity groups. Once a decision has been made that a company is to be sold, the advantages of selling to a strategic buyer – who will be willing to pay a takeover premium and typically pay in full immediately – will often outweigh the uncertainty, and perhaps the longer process, of going public in an IPO. Of course, there are non-financial counter-arguments for selling out to a strategic buyer as independence is lost. This may not happen immediately, as many IPOs begin with the sale of only part of a company to the public, which enables the owners or founders to retain control in the initial period after the listing. This was the case with both Facebook (over 50% of the shares were controlled by founder Mark Zuckerberg after the IPO in May 2012) and the owners of the soccer club Manchester United (who listed just 10% of the club when it went public in August 2012).

M&A deals must look at the synergies and changes brought about through the combination of two previously unrelated companies, while IPOs, venture capital, and other typical corporate finance methodologies consider a company to be a standalone entity.

Synergies

As any strategic M&A deal represents the combination of two companies, there exists in any such transaction the potential for synergies. As noted in Chapter 1, this can be one of the significant drivers to the deal. It is commonly summarized as the “2 + 2 = 5 Phenomenon,” whereby the resulting company has greater value than the sum of its previous two parts. Press releases announcing the deal will often emphasize the synergies expected.

Where do these synergies arise? One of the most frequent places to find savings will be in the headcount. As shown in Surviving M&A: Make the Most of Your Company Being Acquired a book by one of the authors, the average headcount reduction will be 12% of the target company's staff. This derives principally from the overlapping departments (are two IT departments required?). For example, within three months of Liberty Global completing its purchase of Virgin Media in June 2013, a deal that we discussed back in Chapters 3 and 6, Virgin Media announced that it would cut 600 middle and senior management jobs out of a total workforce of 15 000. They explained that as many as one-third of their 120 executive directors and directors would lose their jobs in back-office areas such as finance, human resources, and legal. Importantly, their front-office employees, including engineers and call-center workers, were spared.

There are other areas of savings from synergies as well: similar products (can we reduce our product line because two products are very similar?), manufacturing facilities (can we consolidate production into one plant and close down the other?), management (do we need two headquarters and two heads of each overlapping department?), suppliers (by combining purchasing, can we get greater quantity discounts?), etc.

Synergies form a critical and often sizeable component of the valuation of the target company in an acquisition. For mergers, the synergies often represent an even larger part of the calculation of why the deal makes financial sense as in a merger of two relatively equally-sized companies, there is greater potential for synergies than between two companies of vastly different size. We saw this in Chapter 1 with the case study of the merger of Publicis and Omnicom, who forecast synergies of $500 million post-deal. As with that deal, the focus tends to be on the expense synergies, but the companies merging should still make sure to keep a close eye on other costs. As Michel Driessen, Senior Partner, Corporate Finance at EY, said to us: “Cost avoidance is as important as synergy identification in optimizing value creation in a deal.”

Revenue synergies, where they exist, are typically smaller. Many analysts will discount them completely as they are more difficult to achieve and dependent on more factors outside management's control than the expense synergies.

There are several problems with synergies in M&A deals:

- As a forecast of a business that doesn't yet exist in the post-deal form, the absolute level of synergies is typically a rough estimate only. In hostile deals, where little or no internal due diligence is possible, the figures may be even less certain.

- Uncertain as well will be whether the synergies are indeed possible; as a projection from management before the two companies have combined, it may turn out that the synergies cannot be achieved at all. One author Whitaker in 2012 found that synergies were not achieved in 50–70% of deals.

- Timing is also uncertain. Forecasts frequently assume that it is easier and faster to make the changes for the synergies than is really possible. As Michel Driessen further told us, “In most deals, the company achieves two-thirds of the synergies in the first two years and the remainder in year three.”

- There is also a cost to achieve the synergies. These expenses will occur earlier – and are thus more certain – than the longer-term synergy savings. What if the expenses to achieve the synergies are expended (the cost of mothballing a plant, the payments to redundant staff, etc.) and the savings never occur or are delayed?

The last point is particularly important, and often underestimated. As Michel Driessen told us, a “company should target a ratio of total one-off costs to achieve versus total synergy benefits of between 1:1.5 and 1:1, with the bulk of the one-off costs incurred in years one and two.”

Another consideration relating to synergies is the importance of protecting the core business while at the same time trying to achieve the synergies projected from the M&A deal. As will be discussed in Chapter 10 on post-deal integration, the deal must not overly distract from the core business. In this regard, one corporate development director told us that “we can't just say that we'll generate 10% synergy cost savings or revenues without understanding what the [human] costs behind it are. So on the revenue side, we may decide that we can leverage our investment banking products into a business that we are acquiring that doesn't have investment banking or corporate banking capabilities, but to do that we would need to make sure that we have enough people either on the ground or committed to doing it in order to generate it.”

Lastly, it is critical that the synergy projections be realistic because ultimately the success of the deal will be partly judged by the ability of the newly merged company to achieve those synergies. How to do this? Again, Michel Driessen had some excellent advice: “Internal stretch targets for synergies should be 20% to 30% greater than publicly-stated goals, to increase probability of synergy target attainment. And finally, tie individual and team incentives to achieving synergies, to improve accountability and ownership.”

Therefore, although often critical to the decision and justification of an M&A deal, the synergies must be analyzed very carefully in light of these potential problems. Typically, this is done through scenario analysis and must be based on the best use of business intelligence possible, as outlined in Chapters 2 and 7.

Experts

In order to conduct the financial analyses that will lead to the valuation, most companies employ outside experts, such as investment bankers or accountants, to complement their own internal financial team. Nevertheless, even with such experienced experts, the bidder is always at an information disadvantage because the bidder (and the bidder's advisors) will never know as much about the company as the insiders of the target (and their advisors). This problem is exacerbated in hostile deals, where often, especially in the early stages of the deal, the bidder has no access to non-public information. This is an area where business intelligence techniques must be used to fill the gap with the best information available, bearing in mind our warning in Chapter 6 to be wary of disinformation and the motivations of those providing non-public information.

M&A strategic valuation also differs from the valuation techniques used by financial buyers (also called “financial sponsors”) in the venture capital and private equity world. Most financial buyers look for an exit from their investment in a time frame of five to seven years (on average) with an internal rate of return (IRR) for the entire investment period of anywhere from 15 to 35% (depending on the market: IRR return expectations were very high in the late 1990s but declined soon after 2000; they peaked again in 2007/8 and fell dramatically after the Lehman failure). The exit multiple is usually based on the entry multiple and then the cash flows are computed to determine the total return. This is a very narrow method of valuation when compared to the typical M&A strategic valuation as discussed in this chapter, although this private equity method should be considered by strategic acquirers as one of the many ways of looking at the value of the business. One or more of the bidders or potential bidders could be a financial sponsor, so their method of valuation should be considered carefully.

There exist a number of common myths about valuations in mergers and acquisitions, perpetuated by those who either are considered “valuation experts” or those who do not get involved in the valuations at all. Some of these myths are noted in Table 8.1.

Table 8.1: Myths and Realities about M&A Valuations.

| Myth | Reality |

|---|---|

| The experts (accountants and investment bankers) know how to produce valuations | It is impossible to know the future accurately. Experts have more experience, but it is dangerous to assume that their experience gives them complete knowledge about a particular company or deal. |

| Valuations are accurate | Even with the most rigorous application of business intelligence, valuation is biased in subtle and not so subtle ways, such as in the assumptions used and in the motivations of those producing the valuation. A valuation is never precise and is never quite finished. Which methods of valuation to use and the weight given to each is based more on the experience of the people producing the valuation than any financial model of what is “accurate.” |

| You need many complex models to produce an accurate valuation | Complexity comes with a cost, especially in taking more time to produce and the likelihood that the number of possible errors introduced into the models will increase with the models' size and complexity. More information is not necessarily better than less information. Simplicity is often the best answer. Also, complex spreadsheet models are inherently difficult for others to audit. What is important is finding a price that both the bidder and target will find acceptable. This “market clearing price” is often more based on recent comparable transactions than the very complex valuation models, although the models are often (incorrectly) needed to provide justification for the valuation of the company. |

| You do not need to change good valuations or good valuation models | During the deal negotiation stage, the valuations are often updated daily. Each input should change as new information becomes available. Internal and external markets change: stock markets, interest rates, risk premiums, economic growth, political risk, industry information such as legal or tax changes, new technology, and company-specific information such as new financial data, management changes, and competitive actions. Even the methods of valuation used may need to change during a deal. |

| You cannot value start-up companies with no earnings history | Valuation is admittedly difficult when a company is at the start-up phase when it likely has negative earnings and low revenues, little or no sales history, and perhaps even with very few direct competitors offering comparables (and even if similar competitors do exist, they are not likely to all be at the same stage of their life cycle as the firm being valued). Difficult doesn't mean impossible, but sometimes creative methods need to be used. |

Adjustments to Financial Statements

Specialist M&A analysts look at financial statements differently from analysts considering a company as a going concern (accountants and equity research analysts, for example). In a merger situation, not only is it important to determine the financial health of the target company, but the balance sheet and income statement of the target itself may be used to finance the deal.

For the balance sheet, consideration must be given to the following items. Some assets, such as cash and marketable securities, can be used to finance the offer as that cash will be available to the bidder when they take over the company. In the same way, accounts receivable and inventories can be used, although for each of these other categories, a discount must be made because they cannot be exchanged into cash for 100% of the book value. Property, factories, and equipment must be revalued to their current market level, as these otherwise are usually shown on the balance sheet at historical cost which may even have a depreciation account attached. Other items of value are the intangibles, which notably are often valued on the balance sheet at a figure that is far different from – usually below – the value of those assets to the bidder, although similarly there may be intangibles on the balance sheet (such as goodwill related to earlier acquisitions) which do not provide value to the current buyer.

The liability side of the balance sheet will also require adjustment. This is certainly true of any debt that is fully repayable to the bank or bondholder upon a change of control, such as an acquisition or merger. It is important to keep in mind that many debt instruments will require repayment with the “change of control” that occurs in an M&A deal. Hidden liabilities must be included, such as the potential legal settlements and redundancy payments which were discussed in the due diligence chapter.

Likewise, the income statement needs recasting. Depreciation has a large impact on cash flow and the accounting method used for it can affect the income statement (especially if the target uses different depreciation and amortization methods than the bidder). This is true of inventories as well, as some companies use the FIFO (first in, first out) method while others use LIFO (last in, first out). There will also be income statement items that will be eliminated (or added) with the new owner, such as employee benefits and travel.

All of these considerations drive the production of cash flow statements. Cash flow statements are preferred over income statements for M&A valuation as typically they are subject to fewer possible manipulations, yet the above adjustments still need to be made. They are also particularly important when looking at the new company's ability to service the debt that it may take on to finance the acquisition. Thus, in looking at the target company, the goal in the financial statement analysis is to produce a cash flow that most accurately represents the post-deal environment and activities.

Total Deal Cost

In assessing the economics of a deal, the shareholders and other analysts will assess whether the gains from the merger will exceed the costs. In an M&A deal, the costs can be significant. Naturally, there is the expense of the target company: how much the target shareholders will need to be paid to part with their holdings, which includes the acquisition premium. Then, there are the “known” and relatively easily calculated (but often very high) expenses, such as the fees paid to the investment bankers, lawyers, accountants, and other professional advisors and the expenses of taking over the new company, including debt borrowed. Opportunity costs and post-deal integration costs (see box below) are almost impossible to quantify accurately, even with the best use of business intelligence, before the deal closes, although this should not be an excuse not to do so. Therefore, a complete financial analysis should include an attempt to bracket these costs, perhaps by providing a range of possible values.

Public Company Valuations

It is much easier to value public companies, because in the public market there exists at all times a simple value for the company: the market capitalization (which is the stock price multiplied by the number of shares outstanding). In an M&A transaction, the easiest method may appear to be the public value of the company (the stock market value of the outstanding shares) plus the control premium.

Unfortunately, this valuation method is not as simple as it may seem. For example, which stock price should be chosen to value the company?: Future stock price projections from analyst reports? The most recent share price, such as that on the first day of negotiation? The historical average? And if the latter, over what period? If the historical period chosen is recent, then a takeover premium may already be reflected in the stock price, especially if there has been takeover activity in a competitor's stock or rumors of the company being targeted. This again shows the reason why M&A valuation is an art and not a science.

Private Company Valuations

Although the principles of valuation of public and private companies are similar, the valuation of private companies is much more difficult, for a number of reasons. First, pre-analysis is normally not possible because private companies' financial information is not usually publicly available. Little or no data will therefore be available when negotiations start and, even when it does become available, it may be much more limited than for a public company. The financial statements of a private company may not have been audited and therefore may not be as reliable as for public companies. Financial statements may contain many expenses from doing business that are not really costs but rather a way to compensate the owners (a company car or spouse travel on business trips, for example). Also, private companies may have greater flexibility to show higher costs in order to lower taxes: for most private companies, keeping taxes low is a primary concern and showing high “paper” profits is less important as they don't have to please the stock market. Lastly, the standard risk parameters for estimating risk and return, such as the use of an equity risk factor such as “beta,” will not exist for private companies as they do not have publicly-traded shares.

Since private companies cannot be purchased except in friendly deals, it should usually be easy to gain access to the company accounts and to senior management in order to get the information to make the adjustments to the accounts, although this may not occur until the discussions are well advanced.

Valuations and Business Intelligence

In order to get around these problems, if the purchaser is a publicly listed company, the income and cash flow statements of private companies being acquired must be recast by adjusting for the items that are most commonly accounted for differently:

- High owner's compensation is often the most tax-effective way for earnings to be distributed to the owners of a private company.

- Travel and entertainment expenses are often higher than they would be in a publicly held firm and represent another form of owners' compensation; these may include spousal/family travel and business trips linked with holidays, which wouldn't be allowed in a corporate travel policy.

- Pension contributions as a future form of owners' compensation.

- Automobile expenses, used for personal trips as well as business; perhaps the brand and, therefore, value of the car would be higher than allowed in a public company.

- Insurance, which covers both personal and business areas.

- High office rent payments if offices are more “prestigious” and costly than necessary (although the inverse can also be true).

When valuing a private company which is being purchased by a publicly held company, these extra expenses will typically be deducted from the expense lines and therefore earnings will be higher. However, there may be other expenses which offset these “savings.” Once the private company is part of a large corporate, it may be internally “taxed” with head office and overhead management charges. Be careful in using these extras to value the target as they usually do not represent increased incremental expenses to the newly combined organization, but rather a mere reallocation of expenses which will remain whether the acquisition is made or not.

No matter whether the buyer of a private company is also a private company or not, when determining the price to pay and the ultimate value to the buyer, the starting point will usually be similar for public companies – as these are the companies on which data is available. From that starting point, adjustments will be made as noted above plus further adjustments because the company is private (usually starting with a liquidity discount of approximately 20% to reflect that the ownership is not as easy to sell if private). Then the values will need to be further adjusted because of the differences between the companies, such as whether the product lines are similar, overall size and profitability, leverage (amount of debt financing the company's operations), and other balance sheet items, such as available cash, the amount of receivables or payables, inventory, etc.

Alternative Pricing Methods

There are many ways to calculate the appropriate price for companies in an M&A situation. Some of these methods overlap, and in some transactions certain methods may not even apply. Some of the most common methods are listed, and discussed briefly, below:

- Liquidation value is the value that the owner realizes when the business is terminated and the assets are sold off, including all the costs of liquidation (commissions, legal, and accounting):

- Orderly liquidation: assets are sold over a reasonable time period so as to get the best price;

- Forced liquidation: assets are sold quickly, such as through an auction sale, usually because of bankruptcy.

- Comparable market multiples (otherwise known as “market ratios”) are commonly used where comparable public companies and similar deals exist. Depending on the company and the industry within which the bidder and target operate, the following can be used:

- Financial statement multiples based on the total deal price: deal value as a multiple of earnings or net cash flow (often a default value for almost any company, where available, but not possible for companies with negative or negligible earnings), sales (used for retail companies and telecommunications firms), and book value (financial services firms, as noted earlier, or any firm with a liquid and marked-to-market balance sheet);

- Production or business activity multiples based on total deal price: deal value as a multiple of units produced (e.g., consumer product companies), reserves (extractive industry companies, such as metals and mining firms or oil exploration companies), or any other relevant business factor (such as, for some internet companies, the number of webpage hits, especially where the financial statement multiples are not available because the company is in the start-up phase when there are no earnings or revenues yet).

The best market ratios to use would be those for recent similar M&A deals as these would already incorporate the premiums paid. It is also important to note any recent or projected growth in the underlying ratio basis (that is, if earnings have been growing rapidly, this needs to be built into the analysis), leverage and other factors, as noted above. “Total deal price” in the above ratios refers, in a public deal, to the consideration (cash plus shares, including any deferred payments) paid to the target's owners; this therefore includes any premium on the existing market capitalization.

Both of the above methods determine the price because they are based on other deals that have occurred (or, in the case of liquidation value, a distressed situation). They do not reflect the value to the buyer, which can be determined by running a discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis. DCF analyses are used when there is sufficient information available to forecast future earnings and cash flows for a projection of the potential of the company. Because it uses the concept of net present value (NPV), it is also known as the “NPV method.” Best is to use future free cash flows (FCF), which account for anticipated future capital expenditures; typically a five-year period is selected. The cash flows in future periods are discounted back to today as is a terminal value of the company which represents the value of the company as an ongoing concern. As noted above, the cash flows should reflect the incremental cash to the newly combined company, not the acquisition as a standalone entity or with corporate overheads allocated to it. Synergies with the existing business should also be included and this is the most effective method to use when significant synergies are projected.

For completeness, an analyst should run different scenarios regarding the expected future performance of the company (typically three scenarios are produced: optimistic, most likely, and pessimistic, although sometimes more scenarios are used), the projected outcome of which should be a weighted average or a simple average of these scenarios. Note that the probabilities assigned to the different scenarios can be different; there is no need for the probability to be the same for the high and low cases.

For some owners, another check on price is to calculate the payback period, which is the amount of time it takes until incremental new earnings equal the purchase price.

Lastly, capitalization of earnings is used when there is a relatively constant rate of growth in the target company and when its post-acquisition structure will be similar to the pre-merger structure (that is, when the acquired company will operate as a semi-autonomous or independent division of the new parent). The capitalization rate is the reciprocal of the price/earnings (P/E) ratio and the payback method: thus, if the P/E ratio is five or the payback period is five years, then the capitalization rate is 1:5 or 20%. Remember to use the P/E ratio based on similar deals conducted in the industry and not the more common financial P/E ratio used to value a company's ongoing stock price.

This method therefore becomes easy to do on the back of an envelope if discussions about a deal start (as often happens!) serendipitously, say in a restaurant or airport lounge, and both parties want a ballpark figure to determine if discussions can or should continue. One needs only to know the industry's acquisition price/earnings ratio (which a senior manager may already know from his or her knowledge of recent deals among competitors) and then to divide the most recent earnings for the current year projection by the reciprocal of that figure. The resulting number is not the final valuation, of course, but may be a starting point from which negotiations can continue.

Other methods can be used as well, including real options, dividend discount models, and a number of proprietary valuation techniques developed by the investment banks, accountancies, and valuation firms. These are beyond the scope of this book to discuss, but the Bibliography contains some excellent resources on valuation.

Assumptions

All industries, companies, and deals are different. One must therefore be especially careful about the assumptions used, as small changes can make large differences (see box above). Different practitioners will have very different approaches to valuation.

- In using industry ratios, the target firm's P/E may be different from industry P/E because:

- The target's expected earnings growth may be different from the industry's average earnings growth.

- The firm's risk factors may be different from the industry's because of geography, management, its marketing plan, or other factors.

- The company may be a mix of businesses; in this case, an attempt should be made to use a P/E ratio for each division separately – multiple P/E ratios would then be used and applied against each appropriate line of business and subsequently re-aggregated to determine a hybrid P/E for the combined businesses.

- Buyers will value assets differently from sellers. For example, the company's assets may be worth more to its buyer than its seller due to synergies with the new business. The buyer may also plan to use assets differently, including selling some of them upon change of control.

- The impact of non-operating assets (assets not used in the operations of the business) needs to be taken into account. These should be valued separately and added to the earnings valuation. An example of this is high value real estate not involved in the business.

- Minority discount: if valuing a minority share and not a controlling position, then a minority discount needs to be applied to the market multiples. The value of a minority interest is less than the proportionate share of the fair market value of 100% of the company because the minority interest lacks control. A single minority stockholder can, at best, only elect a minority of the board of directors and will otherwise have little ability to determine management, strategy, or the finances of the company.

- When an investment lacks marketability (as with a privately held company), it is often more difficult to sell to buyers. Also, because of the differences in accounts noted earlier in this chapter a discount should therefore be taken when market multiples are used from public companies to value a private company.

- The impact of risk arbitrageurs must also be considered as discussed in Chapter 6. These traders will purchase minority positions in stocks in which they believe a merger or acquisition will take place. These positions are considered “hot money” and the arbitrageur will sell the position strictly for financial return. If a company has a substantial portion of its shares in the hands of arbitrageurs, this may make an acquisition faster and easier, although not necessarily less expensive.

- It is important to be explicit about exactly what is being included and excluded in a deal, especially when acquiring only a part of a company. Some participants will refer to enterprise value (the value of the whole company: from an asset valuation perspective, this is the value of the assets, which also equals the debt plus equity) whereas others will refer to the equity value (which is the value of the company excluding outstanding debt). Without clarity as to what terminology is being used, very different assumptions on price will be made.

Mergers vs. Acquisitions

Another issue in valuation is determining whether the deal is in fact a merger or an acquisition. If it is an acquisition, then there should be an acquisition premium because the target's management and shareholders give up control and therefore require a premium to be compensated for this loss of control. If the deal is structured instead as a merger, the two companies are equals, therefore future control is shared and no premium is required as neither side loses control – or perhaps both sides do equally!

Multiple Valuation Methods

It is important to use as many valuation methods as possible in each transaction. There will rarely be a situation where only one method should be used and even each individual method may have several scenarios, as noted earlier in this chapter.

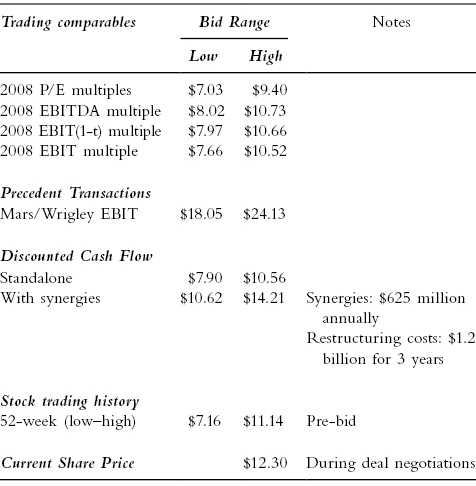

Since not all methods are equal in terms of certainty or reliability of data or relevance to the deal, when using multiple methods they must be weighted to come up with a single figure (see Table 8.2 for an example of this from the Kraft/Cadbury deal). Most external advisors will show a wide variety of methods of valuation in their fairness opinions and pricing recommendations; however, it is ultimately the board's responsibility to determine which figure(s) to use.

Table 8.2: Valuation and pricing methods used by Kraft in its acquisition of Cadbury ($/share).

How do you determine the relative weightings between the different valuation methods and their scenarios? Think about what aspects of the business tend to give rise to its value:

- Is the balance sheet liquid? Then book value may be most relevant.

- Is it assets that drive the company's value? Then net asset value should have greater weight than other methods.

- Is it the company's earning power driving value? Used most often in private equity and venture capital valuation models that depend on the development of a profitable earnings stream; then give future cash flow methods more weight than the other methods.

- Are there recent similar transactions? Then give more weight to the market multiples using recent deals.

The ultimate spreadsheet in many deals being used for pricing and valuation may have more than 30 methods of calculation, including the different scenarios and base figures for some of the methods. Of course, in the final weighting, many of these will have minimal impact on the final result, but it is useful for the decision makers to have the figures to compare and consider.

Ultimately, even a “final” figure determined through the above methodology will serve only as a starting point. Other factors will have to be considered, such as the costs of the deal, as discussed earlier in this chapter. The negotiating strategy will also have to be considered: will the first bid be very low with an expectation that the final price will be higher or will a bear hug strategy (see the next chapter) be employed, whereby a high price is presented first?

Role of Business Intelligence

Naturally, no matter how good the analysis, there is no deal unless both the buyer and the target agree on a price. Not all buyers and sellers are rational. Determining what is likely to be acceptable to the other side requires the use of business intelligence.

A key area where business intelligence is critical is to determine how to pay for the deal. Knowing the needs of the principal target shareholders is an imperative. The issue of payment is of interest not just to the bidder (who will need to know whether it can afford to make the purchase), but also to the target (who will need to know whether the bidder has the ability to pay for the company being sold). Also important is how the payment is structured – whether cash, debt, stock, hybrid instruments, or some combination of these, plus the timing of the payment in case there is a deferral of all or part of the consideration.

If there is uncertainty about key aspects of the deal – often uncovered because of the effective use of business intelligence techniques – then the payment of the purchase price and even the closing can be structured to reduce the risk to the purchaser. This is very common in the private equity and venture capital industries where “earn-outs” are used to retain both key senior managers and clients, and to make the final price dependent on the performance of the company or division. “Earn-outs” also reduce the upfront payment by the acquirer and in many instances maximize the price received by the target if they achieve the robust earnings growth that they expect, but that would otherwise have been discounted by the purchaser. Other partial payment deals or staged acquisitions can be dependent on additional factors, such as regulatory approval and R&D risk, as shown in the box.

Financing the Deal

When an acquisition is to include an element of cash paid to the target shareholders, the purchaser is faced with the issue of where to get the cash from (unless the company is fortunate enough to have it already at hand, which may often be the case for acquisitions of companies much smaller than the bidder). Broadly, the choices for obtaining new cash are either to issue new equity (issued as rights to existing shareholders or placed out to new shareholders), to take on new debt, or to sell a piece of the business in order to help pay for the acquisition. Some of the payment can also be deferred (typically subject to performance criteria) and in some instances the seller will even provide financing.

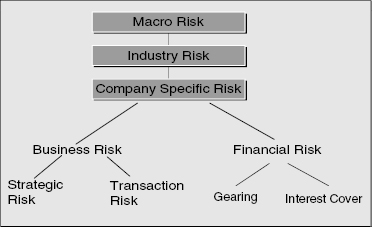

It is not only the target's needs that drive the financing structure. The buyer must also know its own financial situation well enough to make sure that it can afford the deal in both the short- and long-term. In putting together the financing package, the acquirer must therefore balance business risk and financial risk (see Figure 8.1).

- Business risk is the inherent risk associated with the operating profits and the cash flows of the company. It is composed of strategic risk and transaction risk:

- Strategic risk is the long-term risk of operating in a particular economy, a specific industry (at a stage of its cycle), and with a specific competitive strategy;

- Transaction risk is the risk of an interruption of the firm's short-term asset conversion cycle (“business cycle”), that is, the conversion of cash into products/services and then back into cash through sales.

- Financial risk is the risk associated with the type of funding used to finance the business (that is, the capital structure of the deal). Financial risk is the risk to the company of defaulting on its debt obligations. It is measured and assessed by both gearing and interest cover:

- Level of debt to equity (“gearing”);

- Ability of the company to service the interest on its debt (“interest cover ratio”).

High business risk should be matched by low financial risk or vice versa. Of the two “risks,” it is a great deal easier for management to adjust or change the financial risk of a company than its business risk.

There are three major areas that will be considered by the acquirer and its advisors in arriving at the financing decision:

- Transaction details, including short-term dilution (earnings per share and impact on existing shareholders), balance sheet gearing, and interest coverage ratios.

- Balance sheet management, such as the expected long-term cost of the financing instrument and the flexibility to restructure the balance sheet.

- Getting the deal done: issues of confidentiality, speed, and other factors unique to the company or transaction, such as knowing well what the other side wants.

If the acquirer decides that it is going to sell a business division to pay for the acquisition either partially or fully, it has several choices. The first is whether to sell an existing division (presumably one which is both non-core and raises enough cash) or a division of the company being acquired (which is a transaction that can be done, as the requirement for the cash to fund the acquisition occurs at the same time as the buyer takes control of the company and is therefore able to sell it). Either of these funding strategies can be arranged prior to the deal announcement. This may enable the seller to achieve the best price as there is less time pressure (if done early enough). If it cannot be arranged pre-deal closing, a bridge loan may be necessary to cover the time between purchase of the entire target and the sale of a part of it.

Glencore Xstrata, the mining and commodities trading company formed from the merger of Glencore and Xstrata in 2013, which we discussed in Chapter 7, provides an example of a non-core asset being sold to finance that deal. In a previous acquisition in 2010, when Glencore purchased Viterra, a Canadian grain company, one of Viterra's divisions was Dakota Growers Pasta, which made pasta. This business was sold soon after the merger of Glencore and Xstrata. Often such forward planning is not possible, particularly if the deal is somewhat opportunistic in nature.

There is also evidence that companies go public in order to raise cash to purchase other companies. For example, when Twitter went public in November 2013, raising $1.8 billion, there was a lot of speculation in the press that they would use the funds raised to make acquisitions. Facebook, following its IPO, purchased WhatsApp in 2014 for $19 billion after buying Instagram for over $1 billion in 2012.

Conclusion

To many who have participated in M&A deals or analyzed them, pricing, valuation, and other financial issues (such as identifying the appropriate financing mix) are the most important factors in determining the success of any M&A deal. Richard Smucker, CEO of the food company J.M. Smucker Co., commented on this when he told Bloomberg in November 2013, “We want to make sure that we are doing the right acquisition at the right price, so there have been a few that we walked away from because the prices have been too high. And we think a great brand at a bad price is still a bad acquisition.”

However, “valuation” is actually only one of many important areas and often not the most critical: we have seen earlier how the wrong merger strategy can cause a deal to fail and we will later discuss the other principal factor in determining success: post-deal integration, including human resource issues. Ultimately, the most important factor in pricing and valuation is finding a narrow range which allows both sides to negotiate all the other non-financial details of the transaction. Only then will a final price be agreed.