Chapter 5

Critical Thinking Is Like . . . Solving Puzzles: Reasoning by Analogy

In This Chapter

![]() Creating compelling comparisons

Creating compelling comparisons

![]() Spotting dodgy analogies

Spotting dodgy analogies

![]() Carrying out thought experiments

Carrying out thought experiments

By three methods, we may learn wisdom: First, by reflection, which is noblest; Second by imitation, which is easiest; and third by experience which is the bitterest.

—Confucius

With this chapter's title I don’t mean to imply that Critical Thinking is literally another term for solving puzzles, but instead that the two actions share areas of similarity. The connection is that solving puzzles, like Critical Thinking, involves the use of insight, of creative imagination — the tool that produces that famous ‘Eureka’ moment (see the nearby sidebar ‘Eureka!’). If Critical Thinking is using the same kinds of hidden abilities as puzzle-solving then it’s clearly doing something right.

Brilliant insights are the stuff of legend, whether they’re in science, business or the arts. No one really knows the secret to obtaining them — despite the huge number of books offering tips. But certain strategies do seem to be related, and I take a look at some of them in this chapter. I guide you through the world of analogies (like the one in this chapter’s title), discuss how to make effective comparisons (and how to recognise false ones) and describe some thought experiments that employ analogies and bring people towards thinking critically.

Investigating Inventiveness and Imagination

Creative insight is linked to the imagination, and to people’s in-built ability to make connections between two quite different things.

Take the skills of the imagination. People aren’t taught them very often; they’re always the poor cousin to learning the 3Rs — reading, (w)riting and (a)rithmetic. When I went to school we did do a little bit of art, and reading and writing at least included making up stories. But nowadays, because governments are focusing on making education more business-friendly, art is often reduced to being part of computer studies and writing is all about spelling and grammar.

In this section you can find out why analogies are an essential element in thinking, and why they are often at the heart of creative insights. The explanation involves the very workings of language — in other words I will be trying to use the thing to be explained — to explain it! But bear with me, some of the cleverest people around say that this skill is the gold standard for new and original ideas.

Think of a category, or ‘box’, to which all the items in each line of the following list belong:

- Jupiter, Saturn, Mars, Pluto, Venus

- Three o’clock, tomorrow, the Stone Age, Wednesday, 1964

- Mumps, tonsillitis, Asperger’s syndrome, acute nasopharyngitis, fractured hip

- Minim, deed, tenet, God’s dog, too hot to hoot

Okay, that was pretty easy. But now try to spot the odd one out each time! You can find the answers in the later, appropriately named section ‘Answers To Chapter 5’s Box ‘Em Up’ Exercise’.

Understanding the importance of analogies to creativity

Some researchers looking at the way minds work and how people seem to think place the human ability to see analogies centre stage, and credit it with all the greatest insights and inventions of history.

Anyone who has taken a Critical Thinking test will certainly have been faced with questions like this:

Dog is to rabbit as Cat is to . . . ?

The answer here being ‘mouse’. Why? Because mice and rabbits are both furry and cute? Not at all. Because there is an ‘important’ relationship implied between dogs and rabbits — the former chases the latter. Same thing with cats and mice. It’s also the principle being sought in ‘missing number’ questions like 2, 3, 5, 8, . . . ?

Now Critical Thinking tests recognise the importance of this kind of intuition — the ability to be pick out of a huge range of possible answers the most relevant ideas. The skill is two-fold — first of all being able to consider possibilities (which is a skill of the imagination) and secondly the ability to analyse and select. That skill, is the ‘librarian’ one — the ability to put things into categories.

Watching your language

The great difference between human beings and the rest of nature is that humans have this incredible tool — language — that enables them not only to communicate, but to create and manipulate models of the world in their minds. A Critical Thinker does precisely this whenever he or she tries to tackle an issue. And the building blocks of these conceptual models are words. So to understand and hopefully improve how your mind works, it really is useful to go back a stage and think about how language works. Contrary to popular opinion (reinforced by things such as dictionaries) definitions of words are actually pretty blurry — not so much fixed as fuzzy.

It certainly helps to think about what say, all sofas have in common — is it four legs? Flowery cushions? — and this instinctive ability to put things in the right category requires you to strip away the inessential qualities of things in search of an underlying core. Of course, something could be a sofa even without a flowery cushion. So what is really important to make something a ‘sofa’? I can’t answer that and 2000 or so years ago Plato flailed about ineffectually too trying to nail the issue. The reality is that words are not used tidily — they are used loosely and allegorically.

Even the grand daddy (again, he’s not literally the grand daddy) of the philosophers, Plato, used many analogies, although he sometimes seems to have felt a bit guilty about doing so. (See the nearby box ‘Plato arguing about analogies for more examples.) On the other hand, historically, many English and American philosophers have seen their job as eliminating linguistic ambiguities, and to do away with imprecise, ‘fuzzy’ thinking. Professors tend to see their job like this.

Two great 17th-century English philosophers, John Locke and Thomas Hobbes, prided themselves on the sort of clear, logical thinking that Critical Thinking at its best is all about. They directly blamed imprecise language for much of the world’s ills. Hobbes wrote disapprovingly: ‘metaphors, and senseless and ambiguous words, are like ignes fatui; and reasoning upon them is wandering amongst innumerable absurdities’. (Ignes fatui is literally a phosphorescent light that hovers over swampy ground at night, so Hobbes is using an analogy himself!) For Hobbes, the line of reasoning, the ‘mental discourse’, is true, but problems arise when people try to communicate their ideas, and with the ‘translation’ of thoughts into words. Not here the recognition that conceptual imprecision allows for grand creative leaps.

As Douglas Hofstadter and Emmanuel Sanders say in a book called Surfaces and Essences (Basic, 2013), the history of mathematics and physics consists of a series of ‘snowballing analogies’. Snowballing being a metaphor intended to indicate that the use of analogies steadily increases, as old analogies get used to form new and grander ones. They note that the great French mathematician, Henri Poincaré, was a keen thought experimenter and often used analogies to help him along the route towards mathematical discovery.

Seeing how words play tricks

Even when you try to express yourself very simply, you often find that words can confuse and mislead. Sometimes what you mean by a word may not be what someone listening understands by the same word. Take ‘happiness’ for example. It is such an important idea that it is often claimed to be a human right: ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’. But not all forms of happiness are equally acceptable. You can’t claim taking drugs or smashing up bus stops as a ‘human right’ just because doing so makes you happy. In fact, when people talk about a right to the pursuit of happiness, they mean something more elaborate, something more to do with ‘human self-fulfillment’. The point is, even a very ordinary word like ‘happiness’ which you probably think you know pretty well already, has enough ambiguity in it to cause problems. The key thing for a Critical Thinker is to think about the context that words are used in. Who is using the word, who is being talked to? What is the social and scientific context?

There’s a huge debate to be had about the extent to which Ancient philosophy is literal — did the Ancient Greek philosopher Thales really think that the Earth floated like a beachball in a universe of water? Or was he maybe onto something more subtle, that the Earth is part of an invisible sea of energy? Or was he using water allegorically to mean that which flows and changes? The view you take of analogy can radically change how you read texts. People usually take Thales’ words pretty literally, and then chuckle over how simple his ideas were. (You can read more about this in the nearby sidebar ‘Philosophers arguing about analogies’.)

But within science and mathematics, Einstein indisputably wears the hat of the great metaphorical thinker. For more details and how Einstein’s famous formula of E = mc 2 came to him when he spotted a crucial similarity between two otherwise very different things, check out the nearby sidebar ‘Einstein’s route to insights’.

One of Einstein’s early analogies was of himself as a boy running down a pier with light as a series of waves rolling in from the sea. In this case, the analogy obviously reinforced his view of light as, well, ‘waves’, the view that he would free himself from only with difficulty later. Similarly, Einstein — like everyone — struggled against the common-sense view of light, which his theory treated as weighing something. Yet how can light ‘weigh’ something? It's hard to get much lighter than, well, ‘light’.

The thing with imaginary examples is not to let them take over and start dictating policy (see the nearby sidebar on Darwin), but to remember that they are, well, just imaginary examples.

Equally, words can confuse and mislead, as the unconventional American anthropologist-cum-insurance man, Benjamin Lee Whorf pointed out as part of his investigations into the workings of language.

One example Whorf gives is of workers in a factory smoking near a drum full of highly flammable petroleum vapours. The workers are ignoring a notice which says: ‘DANGER: EMPTY PETROLEUM DRUMS’. But, because everyone associates something being ‘empty’ with the absence of anything, the warning is ineffective — a bit like a notice which says: ‘BEWARE OF NOTHING’! The message really needed was ‘DANGER: PETROLEUM DRUMS FULL OF FLAMMABLE VAPOURS’!

Confused Comparisons and Muddled Metaphors

When you start to look, you soon find that lots of people make their points using analogies rather than arguments. Truly, an analogy is worth a thousand words. In Critical Thinking terms an analogy is valid when it identifies a similarity between two different things that sheds light on a particular issue. For example, the premises of an argument are like the foundations of a building. If they are weak or flawed, then the argument will collapse.

But what about analogies that don’t really work? In this section I discuss false analogies, which are comparisons that mislead rather than shed light. This may be because:

- The items being compared do not actually have the factual properties attributed to them by the comparison.

- The comparison actually obscures differences that are more relevant or important than the similarity.

- The two items just are not similar enough to make the comparison work.

- There are plausible comparisons and links between two things — but the comparison made simply isn’t one of them.

- The comparison, although not necessarily wrong, excludes important other possibilities.

An example of a good analogy might be that one about the trapping of the sun’s heat in the Earth’s atmosphere by invisible gases. This physical effect is often compared to the trapping of heat in a greenhouse by the sheets of glass. This analogy is so common that it has become a noun — the ‘greenhouse effect’. And it’s probably valid as the gases do have a similar effect to sheets of glass.

However, what about a comparison between running a country and running a corner shop? Such comparisons are made, usually to demonstrate that government’s must make their activities profitable and not behave like charities ‘or else they will go bust’.

This is surely a misleading comparison, as (for example) the aims of governments are to help people, whereas the aim of a corner shop is to make money. Secondly, when a government helps its citizens, for example through spending on education and health, it both saves money later and likely creates money by deepening the pool of skills available for industries and other businesses to draw on.

Seeing false analogies in action

You encounter false analogies repeatedly in everyday life. For example, advertisers often compare their products to quite different things, in the hope of persuading potential customers that in some crucial respect a similarity exists between the two items: driving a car is like flying a fighter jet; eating some chocolate is like lying on a white sandy beach in paradise. The only link offered is the ‘feeling’ the consumer is supposed to get in the various cases. However, since hardly anyone really gets those feelings, the comparison seems a bit false.

Another issue that brings up some dodgy if not downright false analogies is whether or not some kind of plan applies to the universe or whether the world, and everyone on it, just emerged by chance (through the principles of natural selection, the principles which ensure certain combinations succeed and spread and others disappear). Nowadays scientists think that they can show ‘almost’ all the steps to explain how the incredibly complex universe could’ve emerged from, if not nothing, certainly something very simple.

Whatever the truth of the matter, one thing is clear: the debate about whether or not an all-knowing being is needed to create the universe has produced more than its fair share of ingenious comparisons. Creationists — who think that God created the universe according to a plan — like to point out that the world is made up of many tiny parts that work together with the delicacy and precision of a fine watch. Now a watch, in a sense, is just bits of metal and glass, but to understand what it really is, to appreciate the function of this or that little cog wheel or tiny spring, it does seem true that people need to recognise that it has been ‘designed’ to tell the time by a watchmaker.

So the claim made by the analogy is that to understand the world around us, we need to see each little bit not as merely ‘metal and glass’ but as having been designed to serve a certain purpose. Some people then move immediately to suppose that this ‘designer’ is God. However, there are other ways to end up with a complicated mechanism like the Earth without having to have an incredibly skilled inventor and designer. In fact, biology and geography teachers often use the language of design — or things having particular roles and serving particular purposes — to do this, when they explain, say, bees as being there to pollinate flowers, or earthquakes as the Earth’s way of ‘relieving pressure’ due to the movement of its tectonic plates. So I would say the ‘watchmaker’ analogy for explaining the world around us is flawed — but not exactly invalid. Flawed as, although not necessarily wrong, it excludes important other possibilities.

Uncovering false analogies

For example, complex issues in bioethics are often distorted by the use of false analogies, with research involving, say, altering the genetic code of human embryos being ferociously condemned as creating ‘Frankenstein monsters’. Recall that the original monster was the product of Dr Frankenstein sewing together various bits of dead criminals and bringing it all to life with a massive bolt of electricity from lightning. So the relevant similarity claimed is really the use of science and technology to bring life to organisms that would otherwise not exist with ‘unknown consequences’. That’s true up to a point, but Frankenstein brings with it all sorts of negative associations.

Or consider another ‘old faithful’ of an analogy that goes with the watchmaker one in the preceding section. This is the ‘Hurricane in the junkyard’ comparison that’s intended to persuade people that the universe is simply too complex to have emerged by chance. In its simplest form, it says that human beings could no more have arisen by random natural processes than a hurricane bellowing through a junkyard could accidentally assemble a jet airliner out of the scrap metal!

The idea of a violent storm being quite incapable of creating a highly complex machine is certainly persuasive as a piece of rhetoric. However, it doesn’t take much time to see that with this analogy, like is not being compared with like. The scientific explanation for the complexity of life isn’t that it all arose in one wild ‘roll of the dice’ but rather that it happened after countless (billions and zillions) of rolls of the dice, with the products of some outcomes being favoured over others.

Dry-eyed scientists quickly point out that the theory of natural selection includes a guiding principle, if not a guiding consciousness, which offers a way for complexity to emerge from chaos that’s anything but random.

For example, if rabbits used to have weedy back legs and run quite slowly, a random adaptation that resulted in more powerful legs and helped some rabbits run faster would seem likely to spread through the rabbit population — because the speedy rabbits would have lots of baby bunnies while the slow ones would become dinner for foxes. The guiding principle is . . . survival of the fastest.

Identifying the link in an analogy can often be the key to seeing if an argument is good — or a stinker. Take this one as an example.

- Governments should behave like parents in a family. Parents need to have the ultimate say because they are wiser and their children do not know what is best for themselves.

The idea that the relationship between citizens and governments is like that of children and parents is worth pulling out of many debates and looking at more closely. The supposed link is that parents have authority over children in order to protect them from harm, and that similarly, the state needs to have certain powers over its citizens for similar reasons.

Yet the comparison is misleading in many ways. First of all, government officials may not be wiser than the citizens, whereas parents are — by virtue of their age, and maturity in possession of far more relevant knowledge than (at least) very young children. Teenagers inevitably end up discovering just where parental wisdom runs a bit short! Another way in which the comparison falls short is that parents usually have to ‘do’, certainly to live with, whatever is decided — whereas governments can carry on very well even after forcing disastrous policies on their citizens. No one made Stalin try out his new farming techniques! Finally, most parents, whatever the wisdom of their views, do love and care for their children, but lawmakers and government officials, alas, don’t always have the interests of the common people at heart.

Becoming a Thought Experimenter

Right. Enough theory. Now let’s try some practice. The grand claim made for ‘thought experiments’ is that they are a powerful way to gain knowledge about the world, by means of pure thought, by ‘armchair philosophy’ only. Indisputably, whether they are called thought experiments or not, the approach has had an important role in not only theoretical philosophy, not only in practical science, but in all areas of thought over the centuries.

In this section you get the chance to observe some famous thought experiments in action.

Discovering thought experiments

Although the term is slightly vague (and people use it in different ways), the first ‘thought experimenters’ were definitely philosophers. Seeing how they used the method can reveal something about how Critical Thinkers can use it too.

Here’s the kind of thought experiment that everyone can make sense of, called ‘Schrödinger’s Cat’, after the physicist who invented it. The issue is from science, and concerns the theory — which is the current consensus — that in the subatomic world the existence of particles is affected by whether they are observed or not. Professor Schrödinger thought this was absurd, so he came up with this ‘What If?’ challenge.

The point of the experiment is to illustrate the strange consequences of the theory that in the quantum (meaning very, very small) world, subatomic particles both exist and do not exist at the same time.

Professor Schrödinger’s imaginary experiment seems to put the cat in the same position, of existing and not-existing — which is ridiculous, and that is his point. He thinks it is ridiculous to suppose that subatomic particles can both exist and not exist at the same time, and are affected by whether anyone is watching them. His experiment links our furry friend’s existence to the particle’s state, with a mechanism that is practically possible if rather unlikely. He challenges anyone who says ‘why yes, subatomic particles can both exist and not exist — no problem’ to also say the same thing about cats.

The great advantage of a thought experiment over say, practical research, is ease. Anyone can come up with a thought experiment, and the evidence it provides is free.

Take a question like one that might come up in sociology — whether people are fundamentally good, but are pushed towards bad behaviour by circumstances. Well, one way to investigate it might be to look at lots of prison records and see the backgrounds and experiences of criminals. But another way would be to imagine some extreme examples, and then, simply by using informed guesses or intuition, imagine what would happen next. Plato’s imaginary story of a shepherd who finds a magic ring seems as good a way to investigate human nature. as cataloging any number of ‘real life’ cases would be — and it’s certainly a lot easier to do!

On the other hand, magic rings, like many thought experiments are well, impossible. Can reliable conclusions be drawn from arguments that start with impossible assumptions? Strictly speaking they cannot — as the rule for valid arguments is that the premises must be true. If the premise is impossible, it can’t be true. I'm not going to try to solve that problem though for the technique here — suffice to say that plenty of very practical issues — in economics, in physics, in mathematics — have been explored with thought experiments that include within them completely impossible assumptions. In a way, that seems to be another powerful feature of the technique!

At its simplest, a thought experiment is a simple imaginary example, a ‘what if’. You probably use this kind of example yourself all the time without noticing. Certainly teachers use it in schools, usually to tell children off. ‘What do you think would happen if everyone walked on the flowerbeds?’ ‘What if I decided I wanted to not come to school but to carry on playing football with my friends?’

Another powerful-but-simple thought experiment technique simply involves substituting one element in an argument for another. For example, suppose someone says that it must be wrong to eat dogs as they are often kept as pets. In that case, you can test their claim by swapping the animal in question for another — perhaps ‘horses’. Horses are often kept as pets but are still eaten in much of Europe and even as delicacies in certain posh restaurants. Now this argument doesn’t prove eating horses is ‘right’ — but it does highlight a weakness with the supposed rule.

Dropping Galileo’s famous balls: Critical Thinking in action

As well as being one of the most famous thought experiments of them all, Galileo’s Balls is also one of the simplest.

This experiment is the classic example of a skill that all Critical Thinkers must have. The matter being investigated was whether heavier objects fall faster than lighter objects — the kind of question that you might well suppose called for some practical — not thought — experiments. But Galileo (the Italian philosopher mathematician and astronomer) proved just by ‘thinking things through’, that we have all the information we need already– without needing to start dropping lead weights or so on.

The thought experiment demonstrates the power of the technique for much more important things than mere physics! If you can make sense of why this one ‘works’ then you can really get a ‘Eureka’ moment and insight into the whole notion of reasoning by analogy.

The experiment (but it’s imaginary remember!) starts with Galileo climbing the leaning tower of Pisa, leaning over the parapet and dropping two metal balls — a large ‘heavy’ one and a smaller ‘lighter’ one, and watching to see which hits the ground first. Galileo was thinking of one of Aristotle’s laws, which said that the rate at which an object would move depends on how heavy it is — and rather tidily too. If one weight falls a certain distance in a certain time, then Aristotle said that a half-as-heavy weight would take twice as long to fall.

But Galileo didn’t want to think of feathers and hammers. Instead, he was thinking balls (no sniggering at the back). Which ball do you suppose would reach the ground first? According to Aristotle the large ball would hurtle twice as fast to the ground as the light one. Well . . . maybe. But now here comes the power of the thought experiment technique: imagine that you tie a piece of string between the two balls. Then, what do you suppose would happen?

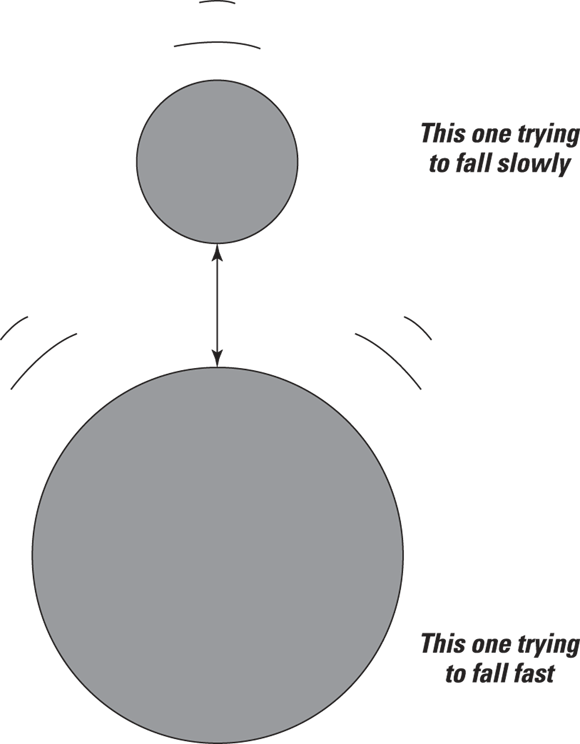

Here’s where the Critical Thinking process starts. First of all assume that heavy objects do fall faster than light ones. In that case, the heavier weight falls as in Figure 5-1, with the lighter weight acting, as it were, a bit like a parachute. Thus the two balls together fall more slowly than the heavy weight would on its own.

Figure 5-1: The clever bit is when Galileo asks us to imagine a string is tied between the two lead weights

On the other hand, when the two weights are tied together and held out over the parapet with the string pulled tight, they’ve effectively combined their weights, becoming one greater weight. Imagine holding the little weight, with the big one dangling beneath it — now as the little weight falls it’s surely going to be pulled down even faster by its big companion!

So, seemingly, putting a cord between the two weights together must make them fall both more slowly and yet, equally, must make them fall faster than when they were released separately. Now, philosophers love a contradiction, which in this case can only be avoided in one way: to assume that the heavy and light weights fall at the same speed.

So, does the experiment work? Yes, physicists know the principle that it established, that all bodies fall with the same acceleration irrespective of their mass and composition, as the Principle of Equivalence. It led directly to Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity, which explains gravity by saying that when the Earth orbits the Sun, it’s ‘falling’ through curved space-time. How about that for the power of thinking!

Splitting brains in half with philosophy

Many thought experiments force you to rethink — critically — assumptions that you had originally taken for granted. This happens even though the experiments themselves may be, a little ridiculous. Remember, that is because it is not the ‘facts’ that are deciding the case, but the reasons used to draw conclusions from them.

A great way to see how thought experiments can test assumptions is to consider a gory one involving cutting brains up. In fact, tinkering with the human body has often appealed to thought experimenters. Typical is an experiment proposed by the American 20th-century philosopher Derek Parfit. Imagine, he says, a surgeon carefully removes someone’s brain and then reinserts it into someone else’s body, in such a way that the original person's memories and personal psychological characteristics were intact enough for people to feel it really was ‘them’ afterwards (only in a new body). Okay?

Therefore, saying which ‘person’ is the ‘real’ Professor Parfit would be impossible. As with the Galileo example (in the preceding section), the result is a contradiction. The idea that one person can become two (or maybe three or four, as neuroscience and surgical techniques improve!) is unacceptable to other firmly held beliefs. The experiment thus forces people to rethink — critically — their assumptions.

Answers To Chapter 5’s Exercise

Here are the answers to this chapter’s earlier ‘Box ’em up!’ exercise. How did you get on?

The categories are fairly uncontroversial:

- Jupiter, Saturn, Mars, Pluto, Venus are all planets.

- Three o’clock, tomorrow, the Stone Age, Wednesday, 1964 are all to do with time.

- Mumps, tonsillitis, Asperger’s syndrome, acute nasophrngitis, fractured hip are all illnesses.

- Minim, deed, tenet, God’s dog, too hot to hoot are all palindromes — words or phrases that read the same backwards as they do forwards.

But deciding on the odd word out is much more subjective than tests often allow and many answers are possible. (In fact, you can often identify more than one category for some lists too):

- Pluto was recently reclassified as a ‘minor’ planet, on account of it being little more than a large rock with an irregular orbit around the sun.

- Tomorrow is the only measure of time that's ‘relative’. Tomorrow will be a different day in a week.

- Asperger’s syndrome isn’t really an ‘illness’. (Did I say it was? You should have challenged me!) It's considered a psychological disorder, characterised by difficulties in social interaction and communication. But an equally valid distinction would be that the fractured hip is the only trauma (injury).

- God’s dog is the only palindrome with an apostrophe. Admittedly that seems pretty arbitrary, but it's still a fact.

Schrödinger’s Cat

One objection would be that cats are conscious too! Maybe they cannot talk, but they can surely tell if they are being poisoned, so that means that if (inside the box) the chain of events was started with the release of the particle by the atom, the cat would not be in a suspended state of being both alive and not-alive anyway — the implausible state that the experiment is supposed to mock.

New ideas don’t come from following routinised methods — powerful though such tools can be in areas where the solutions and strategies are already known.

New ideas don’t come from following routinised methods — powerful though such tools can be in areas where the solutions and strategies are already known. Standardised intelligence tests such as the one I present now often try to measure people’s ability to categorise, but such tests really only measure a very narrow part of the skill — the logical part. Researchers have found that in real life, categorising is much more complicated than that, involving many judgements and assumptions, most of which people aren’t consciously aware.

Standardised intelligence tests such as the one I present now often try to measure people’s ability to categorise, but such tests really only measure a very narrow part of the skill — the logical part. Researchers have found that in real life, categorising is much more complicated than that, involving many judgements and assumptions, most of which people aren’t consciously aware. Certainly, the history of mathematics and physics consists of a series of ever grander analogies, and remembering this can help you make sense of it. Isaac Newton wrote of what he called ‘the Analogy of Nature’, giving as one illustration, possible links between the musical scale and the colours of the spectrum. The great French mathematician, Henri Poincaré, was a keen thought experimenter and often used analogies to help him along the route towards mathematical discovery.

Certainly, the history of mathematics and physics consists of a series of ever grander analogies, and remembering this can help you make sense of it. Isaac Newton wrote of what he called ‘the Analogy of Nature’, giving as one illustration, possible links between the musical scale and the colours of the spectrum. The great French mathematician, Henri Poincaré, was a keen thought experimenter and often used analogies to help him along the route towards mathematical discovery. As you can see, word associations in general and analogies in particular can mislead as easily as they can help provide new insights. Fortunately, Einstein had such a love of conceptual similarities and hidden analogies that making one dodgy comparison never stopped his creative process.

As you can see, word associations in general and analogies in particular can mislead as easily as they can help provide new insights. Fortunately, Einstein had such a love of conceptual similarities and hidden analogies that making one dodgy comparison never stopped his creative process. The term thought experiments has no precise, agreed meaning, but it covers a range of techniques from imaginary ‘what if’ scenarios, to fables and allegories and carefully worked out hypothetical examples, or even models.

The term thought experiments has no precise, agreed meaning, but it covers a range of techniques from imaginary ‘what if’ scenarios, to fables and allegories and carefully worked out hypothetical examples, or even models.

The example of Galileo’s Famous Balls also illustrates several crucial features of Thought Experiments. One is that they all follow the Critical Thinking pattern of presenting a series of assumptions. Another is that there is no attempt to turn the starting assumptions in reality — they are just imaginary starting points. You might say, but why not start with facts? The point is that the focus in a thought experiment is on the argument and reasoning — not on the premises. Galileo’s thought experiment — used to prove one of the most important ideas in physics — is a good way to illustrate this. That’s right, this thought experiment really does prove something and that something really is useful.

The example of Galileo’s Famous Balls also illustrates several crucial features of Thought Experiments. One is that they all follow the Critical Thinking pattern of presenting a series of assumptions. Another is that there is no attempt to turn the starting assumptions in reality — they are just imaginary starting points. You might say, but why not start with facts? The point is that the focus in a thought experiment is on the argument and reasoning — not on the premises. Galileo’s thought experiment — used to prove one of the most important ideas in physics — is a good way to illustrate this. That’s right, this thought experiment really does prove something and that something really is useful.