Chapter 26

Window Barrier and Discrete Barrier Options

Window barrier options are extensions of American barrier options. The difference being that window barriers are active only for a subsection of the life of the option. The two main window barrier variations are front-window barriers (barriers active from the horizon until a specified date prior to expiry) and rear-window barriers (barriers active from a specified date after the horizon until expiry).

Front-Window Barrier Options

Front-window barrier options, also called early ending barriers, have a vanilla payoff at expiry plus single (one) or double (two) American barriers that are active from the horizon but cease to be active on the barrier end date. The barrier end date occurs prior to the expiry date and the window barriers are either all knock-out or all knock-in. Exhibit 26.1 shows a typical front-window double knock-out barrier contract.

Exhibit 26.1 Front-window double knock-out barrier structure

Within a front-window knock-out barrier option:

- If spot trades at or beyond (touches) a barrier prior to the barrier end date, the whole contract expires.

- If spot does not touch a knock-out barrier prior to the barrier end date, at expiry there is a vanilla payoff.

Example: GBP/USD 1yr 1.6000 GBP call/USD put with front-window knock-out barriers for the first month at 1.5500 and 1.6000. With GBP/USD spot at 1.5865, the front window barriers make the contract significantly cheaper; the vanilla is valued at 2.25 GBP% and the window barrier is valued at just 0.25 GBP%. Ignoring smile effects, this suggests that the chance of spot not touching the barriers is only approximately 1 in 9 (the ratio of the prices). Window barrier options are attractive to institutional clients who have a specific market view. In this case, the view is that GBP/USD spot will hold a tight range for the first month before moving higher (if traded live) or before implied volatility increases (if traded delta hedged).

There are two main trading risks on front-window barrier options that can be considered separately:

- Touch risk from the barrier(s)

- Payoff risk (e.g., strike risk from the vanilla payoff at expiry)

Front-Window Barrier Risk

If front-window barriers are knock-out, the risk within the barriers is equivalent to no-touch risk: “Payment” occurs if the barrier levels don't trade. Alternatively, if the window barriers are knock-in, the risk within the barriers is equivalent to one-touch risk: “Payment” occurs if the barrier levels do trade. In this context, “payment” is not a fixed cash amount as it is for a touch option; rather it is the value of the payoff at expiry. The value of the payoff with horizon set to the barrier end date and spot at the barrier level can be thought of as the intrinsic value of the barrier. As usual, the intrinsic value gives the notional of touch option that must be transacted in order to hedge the barrier risk. Intrinsic value on front-window barriers is not static, but it is stable enough for the risks to be effectively offset using a static touch option hedge.

Intrinsic value can be estimated within a pricing tool by moving the horizon forward to the barrier end date and pricing the payoff at expiry with spot at the barrier levels as shown in Exhibit 26.2. Alternatively, the horizon can be kept constant and the expiry can be moved such that the number of days from horizon to expiry is equal to the number of days from barrier end date to expiry in the original window barrier contract. This second approach ignores forward volatility, forward skew, and forward interest rates but in most instances it will give a reasonable guide to the amount of touch risk contained in the barriers.

Exhibit 26.2 Estimating barrier risk on a front-window barrier option

Example: AUD50m AUD/USD 1yr 0.9200 AUD call/USD put with a 3mth front-window knock-out up barrier at 0.9300. The 9mth 0.9200 AUD call/USD put vanilla with spot at 0.9300 has a midmarket price of 2.54 AUD%. Therefore, there is approximately (AUD50m × 2.54% =) AUD1.25m of touch risk in the window barrier.

The trading risk from reverse American barriers is maximized at the end of the barrier life where the P&L difference between touching the barrier or not is maximized. The same is true within window barrier structures; the main risk management challenges occur into the barrier end date.

Payoff Risk

The smile value of the option payoff at expiry is given by the zeta of the equivalent vanilla option. In addition, the probability of the option being active at expiry must be taken into account. Ignoring discounting and volatility surface considerations, for front-window knock-out barriers this probability can be approximated by the TV of a no-touch option to the barrier end date. For front-window knock-in barriers this probability can be approximated by the TV of a one-touch option to the barrier end date.

To remove the effect of discounting from calculations like this on longer-dated trades, fix the forward and set the payout currency interest rates to 0%. This results in zero discounting but leaves the forward drift unchanged.

Combining Barrier and Payoff Risks in a TV Adjustment

The smile risk from the barrier and payoff within a front-window barrier option can be combined into an approximate TV adjustment:

For double-barrier front-window barriers, each barrier will have a different intrinsic so the average intrinsic can be substituted into the above formula.

Example: AUD50m AUD/USD 1yr 0.9200 AUD call/USD put with a 3mth front-window up-and-out barrier at 0.9300.

- Intrinsic Value (IV) = 2.54 AUD% (as per the above calculation)

- 3mth no-touch (since knock-out barrier) TV adjustment = +0.85 AUD%

- Probability of payoff occurring (i.e., 3mth 0.9300 no-touch TV) = 38%

- Vanilla zeta = +0.205 AUD%

Therefore, front-window barrier TV adjustment = 2.54% × 0.85% + 38% × 0.205% = +0.10 AUD%. This compares with the mixed volatility model TV adjustment of +0.11 AUD% shown in Exhibit 26.3. Note how the window barrier in leg 3 shows only one ATM volatility to the final expiry but is only one ATM volatility used to calculate TV?

Exhibit 26.3 Front-window barrier TV adjustment approximation in pricing tool

Trading Risks

Front-window barrier options are long vega to the expiry date (from the strike) and either short vega from knock-out barriers or long vega from knock-in barriers to the barrier end date. Because window barriers have important vega exposures to different maturities it is vital that the full ATM term structure is used for pricing window barriers and that vega risks are correctly bucketed within risk management systems.

If the ATM curve is downward sloping (short-dated ATM implied volatility higher than long-dated ATM volatility), front-window barrier options are particularly attractive to clients because adding front-window knock-out barriers significantly reduces the price of the contract.

Example: USD/CAD 1yr 1.1500 USD call/CAD put is 1.85 USD% premium (7.50% implied volatility). Adding 1mth front-window double knock-out barriers at 1.0900 and 1.1300 reduces the price to 0.50 USD% as shown in Exhibit 26.4.

Exhibit 26.4 Front-window barrier option in pricing tool

The initial vega exposure from this trade is shown in Exhibit 26.5. As expected, vega looks like a double-no-touch vega profile until the barrier end date. Once the barriers are no longer active the vega will simply be that of a vanilla option to the expiry date.

Exhibit 26.5 Front-window barrier vega exposure

The most sophisticated pricing model available should be used when pricing window barriers because they are complex products with significant exposures to the forward smile. For a front-window barrier trade, if spot does stay within the range for the first month, at the barrier end date the ATM curve is likely to be lower than was envisaged at the option horizon. When pricing window barrier options it can be important to take this kind of reasoning into account manually since pricing models do not usually account for it.

It is also important to confirm at exactly what time the front window ceases to be active on the barrier end date. Most often the cut from the payoff is used but this is not always the case.

Front-window barrier bid–offer spreads can be calculated by considering the bid–offer spreads from the barrier risk and payoff risk. The two spreads should be combined because both elements may require risk management attention but the payoff spread should be weighted by the probability of the payoff occurring.

Finally, when assessing the stopping time of a window barrier, remember that stopping time is defined in terms of a single value: the expectation, when in reality it has a distribution. For example, if a window barrier option has a one-year expiry and an active barrier for the first month only, the stopping time may be given as, for example, 70% when the option can never actually knock 70% of the way through its life.

Rear-Window Barrier Options

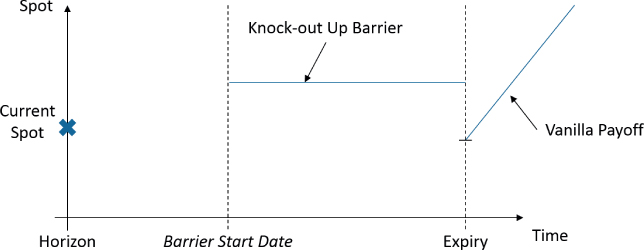

Rear-window barrier options, also called late-starting barriers, have a vanilla payoff at expiry plus single (one) or double (two) American barriers that are active from the barrier start date to the expiry date. The barrier start date must be after the horizon date but before the expiry date and the barriers must either be all knock-out or all knock-in. The type and direction (e.g., down-and-out/down-and-in, etc.) of rear-window single barriers must always be specified since their direction cannot always be determined from the inception spot level.

Exhibit 26.6 shows a typical rear-window up-and-out barrier call option.

Exhibit 26.6 Rear-window up-and-out barrier structure

Within a rear-window knock-out barrier option:

- Spot can go through knock-out barrier levels prior to the barrier start date and the trade does not knock out.

- If spot ever goes above the knock-out barrier level between the barrier start date and expiry, the trade expires. Also, if spot is through the barrier level at the barrier start date, the trade also expires.

Example: GBP/USD 1yr 1.6000 GBP call/USD put with a rear-window double-knock-out for the last month at 1.5000 and 1.7000. Therefore, if spot trades through (below) 1.5000 or (above) 1.7000 at any point in the month before the expiry date, the option expires. If spot is within the 1.5000/1.7000 range one month prior to expiry, the option becomes a standard double knock-out option. The barriers significantly cheapen the window barrier option (0.59 GBP%) compared to the vanilla (2.26 GBP%) and, plus, it allows for a more sophisticated spot view to be expressed.

To assess the smile risk on a rear-window barrier option, price the payoff with no barrier and ascertain its smile value. Then price European barrier and the American barrier versions, each time noting the TV adjustments:

- If the barrier start date is near the horizon, the risk on the rear-window barrier will be more similar to the equivalent American barrier option.

- If the barrier start date is near the expiry, the risk on the rear-window barrier will be more similar to the equivalent European barrier option and a local volatility model may be sufficient for pricing.

This approach gives good intuition about the risks on rear-window barrier options but it is important to appreciate that the rear-window barrier TV adjustment does not simply move from American barrier TV adjustment to European barrier TV adjustment as the barrier start date goes from horizon to expiry. Also, if the rear-window barrier is through current spot, this approach does not work because the American barrier option variation will have already knocked.

It may also be useful to assess the probability of the rear-window barriers being knocked. One quick way of estimating a barrier-knock probability is to price two vanilla options (CCY1 call for an up barrier and CCY1 put for a down barrier) with the strikes set to the barrier level; one expiry at the window barrier start date and one expiry at the window barrier expiry date. The delta of the vanilla options gives a very rough indication of the barrier-knock probability.

Prior to the barrier start date, the rear window vega profile depends on the barrier characteristics:

- For a knock-out barrier, with spot in front of the barrier the contract will be short vega.

- For a knock-in barrier, with spot in front of the barrier the contract will be long vega.

After the barrier start date, the trading risks and vega profile simply become those generated by the equivalent standard American barrier option. As with front-window barriers, for rear-window barriers the most sophisticated possible pricing model should be used. Rear-window barriers usually have a similar bid–offer spread to the equivalent European or American barriers because the magnitude of their trading risk is similar.

Generic Window Barrier Options

In practice, a window barrier option may contain any number of knock-out or knock-in barriers with different start and end dates. For example, if a sophisticated customer thinks that spot will trend lower in a specific way over time, a product with bespoke barriers could be constructed as per Exhibit 26.7.

Exhibit 26.7 Generic window barrier structure

To identify which barriers are most important, remove each barrier in turn from the structure and check the impact on TV: Big TV change implies an important barrier. If there are just one or two important barriers, the TV adjustment on the whole structure can be estimated by considering the smile risk on the important barriers in isolation. This is done by multiplying the TV adjustment of the barrier by the probability of the barrier being live at its start date.

Window Barrier Risk Management

Window barrier options have additional trading risks to American barrier options. Specifically, there are increased exposures to the ATM curve, and additional exposures to the forward smile. Therefore, when pricing and risk managing window barrier options it is important to assess exactly which pricing methodology is used. For example:

- Which ATM volatility curve is used to generate TV? Is only the ATM volatility to expiry used (i.e., pure Black-Scholes), are two volatilities used (one to barrier start/end date and one to expiry), or is the full term structure of ATM volatility used? If only a single ATM volatility to expiry is used, the TV adjustment must take into account the effect of the full ATM volatility curve.

- How are bucketed Greek exposures displayed? Is the vega all bucketed to the option expiry, or is vega bucketed correctly? This is particularly important within risk management.

It is also important to assess what the forward smile looks like within the smile pricing model. Does the forward smile from the barrier start or end date until the expiry look credible with reference to the current volatility surface? If not, that brings the validity of the TV adjustment generated by the model into doubt.

Discrete Barrier Options

Discrete barrier options are like American barrier options except that the barrier is monitored against a fix rather than being monitored continuously. Discrete barriers are monitored against a spot fix in the market, usually at regular intervals (i.e., once a day or once a week). If the fix is through the barrier level, the trade will knock. Therefore, it is vital to know the exact methodology used to calculate the fix.

In terms of pricing, discrete monitoring reduces the probability of a barrier knock compared with continuous barrier monitoring for the same barrier level. The TV of a discrete knock-out barrier option will therefore be higher than the TV of the equivalent American knock-out barrier.

An elegant approximation for adjusting discrete barriers into equivalent continuous barriers was developed by Broadie, Glasserman, and Kou (A continuity correction for discrete barrier options, M. Broadie, P. Glasserman, S. Kou, Mathematical Finance, 1997). To price a discrete barrier option, price the continuous barrier version with the barrier level adjusted using these formulas:

where ![]() is the time between monitoring events:

is the time between monitoring events:

Where ![]() is the Riemann Zeta function (…no, me neither…).

is the Riemann Zeta function (…no, me neither…).

These formulas give good intuition about discrete barriers: A discrete barrier option is equivalent to a continuous barrier option with the barrier placed further away from spot.

Discrete barrier options also present additional risk management challenges. When spot goes through an American barrier level, the resultant barrier delta gap can be hedged in the spot market to leave the delta exposure within the trading position unchanged. However, with a discrete barrier, spot may go through the barrier level in-between fixes. Should the trader hedge the delta gap, or not?

Suppose the trader has a stop-loss order to buy spot at a higher level if a topside discrete barrier knocks out. If spot goes through the barrier level but the trader does not buy spot, the spot rate may do one of two things:

- Continue higher, and when the barrier officially knocks at the fix the trader will have to buy spot at a higher level, hence causing a loss.

- Reverse back lower below the barrier level prior to the fix, and hence the trader was correct not to buy spot, hence causing no loss or gain.

Alternatively, if the trader does buy spot, the spot rate may do one of two things:

- Reverse back lower below the barrier level prior to the fix and the trader will have to sell the spot out at a lower level when it becomes clear that the barrier will not knock out at the fix, hence causing a loss.

- Continue higher, and hence the trader was correct to buy spot, hence causing no loss or gain.

This is the same issue as the restricted spot market open hours case discussed in Chapter 25. This additional risk means that discrete barrier options are often quoted wider than the equivalent American barrier options, particularly on larger-sized trades.