15

Global Project Management Excellence

15.0 INTRODUCTION

In the previous chapters, we discussed excellence in project management (PM) the use of PM methodologies, and the hexagon of excellence. Many companies previously described in the book have excelled in all of these areas. In this chapter, we focus on seven companies, namely IBM, Citigroup, Microsoft, Deloitte, Comau, Fluor, and Siemens, all of which have achieved specialized practices and characteristics related to in-depth globalized PM:

- They are multinational.

- They sell business solutions to their customers rather than just products or services.

- They recognize that, in order to be a successful solution provider, they must excel in PM rather than just being good at it.

- They recognize that that they must excel in all areas of PM rather than just one area.

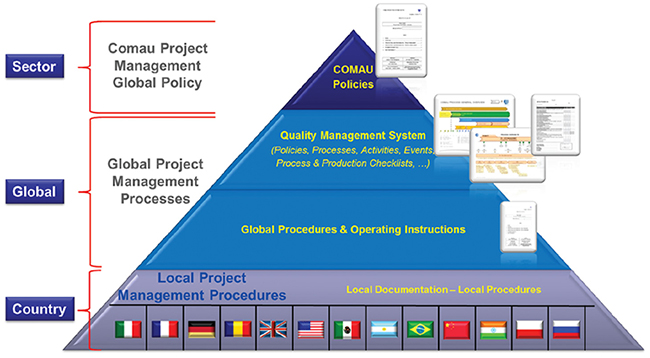

- They recognize that a global PM approach must focus more on a framework, templates, checklists, forms, and guidelines, rather than rigid policies and procedures, and that the approach can be used equally well in all countries and for all clients.

- They recognize the importance of knowledge management, lessons learned, capturing best practices, and continuous improvement.

- They understand the necessity of having PM tools to support their PM approach.

- They understand that, without continuous improvement in PM, they could lose clients and market share.

- They maintain a PM office or center of excellence (CoE).

- They perform strategic planning for PM.

- They regard PM as a strategic competency.

These characteristics can and do apply to all of the companies discussed previously, but they are of the highest importance to multinational companies.

15.1 IBM1

Overview

It has been well publicized over the past number of years that IBM is undergoing one of its most complex and significant transformations since its foundation in 1911.

In addition to being one of the world’s largest information technology (IT) and consulting services company, IBM is a global business and technology leader, innovating in research and development to shape the future of society at large.

Today, IBM sees itself as much more than an information technology company.

In April 2016, IBM’s chairman, president, and chief executive officer, Ginni Rometty, described the dawn of a new era, shaped by cognitive computing and cloud platforms. She described how the IT industry is fundamentally reordering at an unprecedented pace. In response, IBM is becoming much more than a “hardware, software, services” company. We are emerging as an AI solutions and cloud platform company.

Fundamental to the success of this transformation is the skills and abilities of its workforce. Each and every one of us are being challenged to make ourselves relevant to the marketplace of tomorrow. We are all encouraged to undertake at least 40 hours of training each year (Think 40), the majority of which is targeted towards emerging technologies and industry specific expertise.

We are encouraged to have a point of view, be both socially and professionally eminent and be comfortable in a customer facing situation. We are provided with the tools and techniques to enable this objective, including new ways of learning such as video, gaming and interactive eLearning techniques to enable this objective. New phrases are creeping into the everyday vocabulary of our teams, phrases such as how can we “be more agile,” “take more (calculated) risks,” “collaborate better and quicker”?

IBM’s PM Centre of Excellence (PMCOE) is no exception to this transformation. 2017 is the twentieth anniversary of the Centre of Excellence, which clearly shows IBM’s ongoing commitment to Project Management as a key profession within the corporation.

At the heart of our mission is the ongoing requirement to continue enabling and supporting our Project Management Community with industry-leading processes, methods, and tools. However, we are continuing to evolve and challenge ourselves to ensure we meet the demands of our customers, given the continuously and rapidly changing environment we all operate in today.

Complexity

When you step back and look at the scale and diversity of the tens of thousands of concurrent projects being managed by our community, it can be truly staggering. We are not only asking our project managers to manage across the traditional boundaries of time, budget, and resourcing, but we now need to understand and be able to clearly articulate;

- Emerging technologies (e.g., cognitive, Internet of Things, cloud etc.)

- Traditional versus hybrid enterprises (on-premise, off-premise, virtual, etc.)

- Industry-specific solutions (e.g., energy, automotive, public, etc.)

- Platform-specific solutions (e.g., as service offerings)

- Client-specific solutions (e.g., customized solutions, integration across multiple diverse legacy environments, etc.)

The majority of our teams as well as our clients’ teams are invariably global in nature, requiring all of us to become experts in cultural, geopolitical, and sometimes religious differences.

In the following sections, we outline how the PMCOE empowers our PM community. Later on, we discuss future trends and opportunities.

IBM’s Project Management System

Successful implementation of projects and programs requires a management system that addresses all aspects of planning, controlling, and integrating with business and technical processes.

IBM’s structured PM system addresses delivery challenges to reliably deliver business commitments to its clients.

- Risks are clearly defined and managed more effectively because the project is properly defined, within the client’s business environment.

- Productivity is increased by a clear definition of roles, responsibilities and deliverables resulting in faster start-up through the use of knowledge management, less rework, and more productive time in the project.

- Communication is easier and clearer because project teams (client and IBM) form more quickly and use common terminology.

- Client visibility to the project plans, schedule, and actual performance against the project objectives is enhanced, helping to increase client satisfaction.

- Client desired outcomes are aligned to project deliverables.

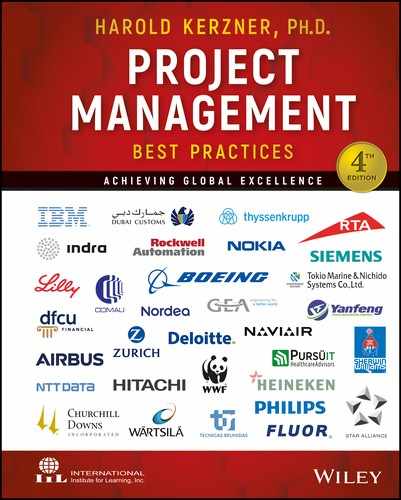

IBM’s comprehensive PM system has three dimensions: coverage, depth, and scope applicable to projects and programs (see Figure 15-1).

Figure 15-1. The three dimensions of IBM’s project management system.

The first dimension is scope. IBM has developed the enablers and professionals needed to manage the delivery of projects and programs of all sizes and complexity. These enablers include: a full-scope PM method, a PM Tools Suite, PM management systems, and a staff of PM professionals that are trained and experienced in these enablers. The enablers are integrated so that they complement and support each other.

The second dimension, coverage, ensures the enablers (method, tool suites, and processes) are comprehensive and scalable to appropriately serve the requirements of the enterprise’s management team, from projects to programs and portfolios. IBM’s PM professionals also have a range of skills and experience from project manager to executives.

The third dimension is depth. Depth addresses the integration of project/program management disciplines and data with the management systems of the enterprise at all levels.

In summary, IBM’s PM approach involves building PM deliverables that have the full scope of items needed to implement and control the delivery of a project or program, have the coverage to be applicable from the top to the bottom of the organization, and have the depth to be integrated into the very essence of the enterprise.

IBM’s structured approach to managing projects and programs includes understanding and adapting to meet our clients’ needs and environment. A PM system is the core of this structured approach.

IBM’s Project Management Methodology

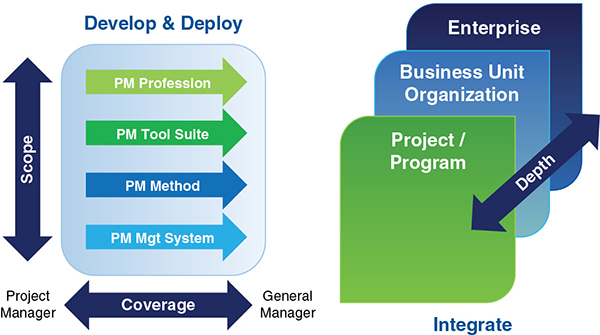

To provide its project teams with consistent methods for implementing PM globally, IBM developed the Worldwide Project Management Method (WWPMM), which establishes and provides guidance on the best PM practices for defining, planning, delivering, and controlling a wide variety of projects and programs. (See Figure 15-2.)

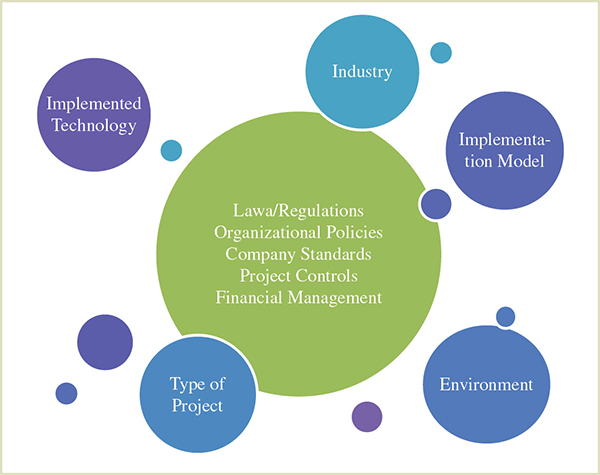

Figure 15-2. Customized project management system.

The goal of IBM’s PM method is to provide proven, repeatable means of delivering solutions that ultimately result in successful projects/programs and satisfied clients.

WWPMM is an implementation of the Project Management Institute’s (PMI’s) Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide)2 for the IBM environment. WWPMM extends PMI’s PMBOK® Guide processes in depth and in breadth and specifies PM work products content.

WWPMM has positioned agile for the PM community since 2008, and WWPMM has been updated through the years to provide more support for projects using agile principles and techniques. WWPMM (agile) is published as a separate PM method and includes additional guidance in support of agile and work products that align with agile techniques. The approach taken was to use agile in generic terms and not select a specific agile technique (such as Scrum, Kanban, XP).

WWPMM describes the way projects and programs are managed in IBM. They are documented as a collection of plans and procedures that direct all PM activity and records that provide evidence of their implementation. In order to be generic and applicable across IBM, the PM method does not describe life-cycle phases but rather PM activity groups that can be used repeatedly across any life cycle. This allows the flexibility for the method to be used with any number of technical approaches and life cycles.

WWPMM consists of a number of interrelated components:

- PM Practices group the tasks, work products, and guidance needed to support a particular area of knowledge

- PM Activities arrange the tasks defined in the PM practices into a series of executable steps designed to meet a particular PM goal or in response to a particular PM situation.

- PM Work Products are the verifiable outcomes produced and used to manage a project.

WWPMM includes a set of templates or tool mentors for plans, procedures, and records that may be quickly and easily tailored to meet the needs of each individual project.

According to Laura Franch, IBM’s WWPMM leader:

The continuous integration of IBM’s project management methodology with other IBM initiatives, enhancements from lessons learned and alignment with external standards are necessary to ensure WWPMM will lead to worldwide excellence in the practice of project management.

IBM uses WWPMM to estimate, plan, and manage application development projects. The key activities involved with this process include:

- Defining, planning, and estimating each aspect of the project

- Organizing, controlling, and managing multiple types of projects (stand-alone, cross-functional, and matrix-based)

- Delivering projects in a common fashion across all platforms

- Capturing, tracking, and reporting performance-based information

- Managing exceptions including risks, issues, changes, and dependencies

- Ensuring project benefits are being realized

- Communicating, on an ongoing basis, with constituencies that are involved in the project, and reporting status and issues to the client’s executive management

- Analyzing the project after implementation to verify that standard processes have been followed and to identify process improvement activities for future projects

These key activities are supported by tools and techniques for project planning, work plan generation, estimating costs and schedules, time tracking, and status reporting.

Keeping with the need to be flexible, the PM system templates and work products can be tailored to meet geography, business line, or client-specific requirements while still maintaining our commitment for “one common project management method.” The WWPMM is available for licensing to IBM clients for their use and for further benefit beyond the scope and scale of a specific project.

The OnDemand Process Asset Library (OPAL) represents an implementation of the WWPMM that supports industry standards, such as the Software Engineering Institute’s (SEI’s) Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI).

IBM’s Enterprise Project Management Office

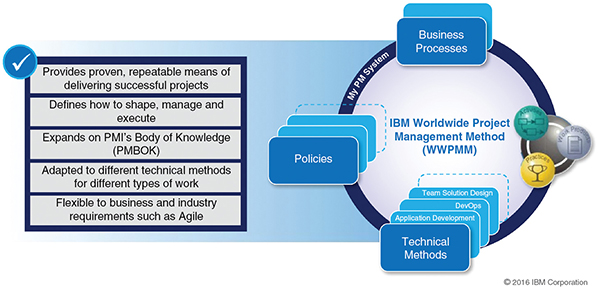

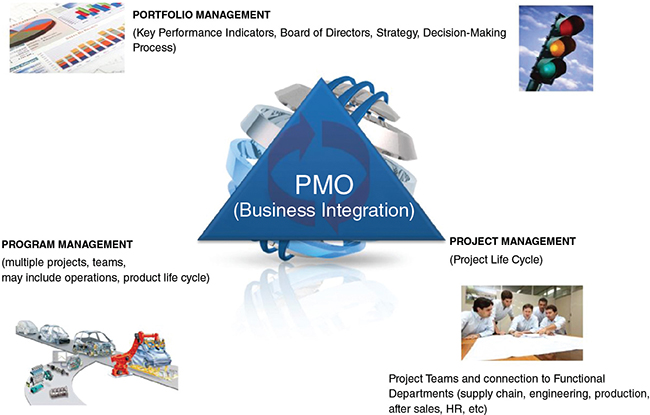

As part of its project-based mission, the IBM PMCOE focuses on the understanding and implementation of project management offices (PMOs). Enterprise PMOs are instrumental to an organization’s ability to define, control and deliver more predictable project results.

IBM’s Enterprise PMOs enable continual alignment with the organization’s strategy, support standardized PM, and focus on talent management. (See Figure 15-3.)

Figure 15-3. IBM’s Enterprise Project Management Office.

IBM’s Enterprise PMO addresses the numerous challenges project teams face by focusing on six key success factors:

- Ensuring all key stakeholders understand the value of PM

- Actively engaging sponsors/executives, addressing their key issues, and generating the support required for the project/program

- Ensuring strategic alignment between business goals and projects executed by enabling executive teams to make informed decisions and choose the right projects to achieve business value

- Using standardized PM practices to support the enterprise strategy and provide the right level of control to reduce risk and ensure successful delivery.

- Using PM Best Practices, assets, and intellectual capital enables organizations to reduce risk and deliver repeatable, high-value, and high-quality solutions.

- Investing in developing project managers’ talent to achieve superior project performance and execution of strategic initiatives

The Enterprise PMO provides the governance, discipline, and resources to effectively manage a portfolio of projects within an organization.

IBM partners with clients to determine the Enterprise PMO suitable to deliver the intended business results and provides methods, processes, and practices for an effective design and implementation of project office capabilities. (See Figure 15-4.)

Figure 15-4. Project Office capabilities design and implementation.

IBM’s Business Processes

IBM’s basic business processes are seamlessly integrated with our methods. Three of these processes directly benefit many of the projects we manage: quality, knowledge management, and maturity assessment.

Quality

IBM’s PM method readily conforms to ISO Quality standards. This means that project managers using WWPMM do not have to spend extra time trying to establish a quality standard for their project as the quality standard is already built into a project’s management system.

Within IBM Global Services, IBM’s business practices require an independent quality assurance review of most projects performed by our worldwide Quality organization. Project reviews play an important role by identifying potential project issues before they cause problems thereby helping to keep projects on time and on budget. The IBM internal reviews and assessments are performed at various designated checkpoints throughout the project life cycle.

Knowledge Management

IBM PM best practices, assets, and intellectual capital represent the combined expertise of tens of thousands of IBM project managers over decades of work and experience delivering projects and programs. Formal PMPM knowledge networks have been established that allow project managers to share expertise in a global environment.

IBM project managers also have access to project intellectual capital including reusable work products, such as architectures, designs, plans, and others. Project managers are encouraged to share their own knowledge and expertise by publishing project work products and experiences. Capturing the best practices and lessons learned on completed projects is fundamental to ensuring future project success.

Maturity Assessment

IBM has developed a comprehensive tools and best practices, the Project Management Progress Maturity Guide (PMG), to assess its current PM capabilities and the PM services it provides its clients and improve them over time.

IBM PM Capability assessment is adapted from SEI’s CMMI, IBM, and industry PM best practices. It measures the degree to which elements of a PM process or system are present, are integrated into the organization, and ultimately affect the organization’s performance. The assessment is performed against 26 best practices through documentation and interviews to look for evidence of deployment, usage, coverage, and compliance. It provides:

- Current capability strengths, weaknesses, and a prioritized list of gaps

- Improvement action recommendations for high- and medium-priority gaps

- An overall maturity level rating for each best practice

For maximum value, an organization should determine a PM maturity baseline; effectively prioritize, plan and implement improvement opportunities; and then measure across time to verify consistent improvement in the organization’s PM capabilities. By understanding the organization’s strengths and weaknesses, actions can be identified for continuously improving PM and achieving business objectives.

As an organization’s PM maturity improves, projects are delivered more efficiently, customer satisfaction improves, and stronger business results are achieved.

IBM’s Project Management Skills Development Programs

Enhancing the integration of the methods, business processes, and policies is the ongoing development of IBM’s PM professionals through education and certification.

Education

IBM’s PM Curriculum is delivered globally and across all lines of business, helping to drive a consistent base of terminology and understanding across the company. Though they are clearly an important audience for the training, attendance is not limited just to project managers. Rather, the curriculum is there to meet the project manager training needs of all IBMers irrespective of what job role they perform. A range of delivery modes are utilized depending on the course content and intended audience. As well as the traditional classroom format, an increasing amount of instructor-led learning is delivered through online virtual classrooms. Extensive use of self-paced online learning provides easy access to curriculum content at a time and place of the learner’s choosing. A Curriculum Steering Committee, composed of representatives from across IBM’s lines of business, provides governance of the development of curriculum content. This ensures that the curriculum continues to meet the evolving needs of all parts of the business.

The PM Curriculum is arranged into four distinct sections.

The Core Curriculum addresses the fundamentals of PM. Employees with limited, or no, prior knowledge can use this section of the curriculum to gain a solid grounding in the disciplines of PM. Introductory courses lay the foundations and more specific courses build on these to develop capabilities in PM systems, contracting, finance, project leadership, and IBM’s WWPMM. A separate integrative course completes this section of the curriculum by drawing together the theoretical learning from the earlier courses and blending that with a focus on the practical application of that knowledge.

The Enabling Education section provides the opportunity to build on learning from the core curriculum and deepen PM skills in specific areas. This would include more in-depth training on topics such as leadership, training in the use of specific PM tools, and more situational topics such as working across cultural boundaries.

The Program Management section is focused on enhancing general business skills expected of more senior roles and on providing project-based tools and techniques needed to manage large programs with multiple projects and business objectives.

The Understanding the Basics section contains courses aimed at employees who support or work on project teams. Basic introductory courses on PM provides them with an understanding of how projects are run and key terms but does not seek to develop them into project managers.

As we have already noted, the PM Curriculum provides training to people in a wide range of job roles, not just project managers. Conversely it is also the case that the PM Curriculum does not set out to meet all the learning needs of IBM’s project managers. For example, project managers will also require a range of skills specific to their operational context (e.g., leadership, industry expertise, culture, etc.) and this will be drawn from IBM’s broader learning provision.

Certification

The PM profession is one of several IBM global professions established to ensure availability and quality of professional and technical skills within IBM. The PM Professional Development initiative includes worldwide leadership of IBM’s PM profession, its qualification processes, IBM’s relationship with PMI, and PM skills development through education and mentoring. These programs are targeted to cultivate project and program management expertise and to maintain standards of excellence within the profession. The bottom line is to develop practitioner competency.

What is the context of a profession within IBM? IBM professions are self-regulating communities of like-minded and skilled IBM professionals and managers who do similar work. Their members perform similar roles wherever they are in the organizations of IBM and irrespective of their current job title. Each profession develops and supports its own community including providing assistance with professional development, career development, and skills development. The IBM professions:

- Help IBM develop and maintain the critical skills needed for its business

- Ensure IBM clients are receiving consistent best practices and skills in the area of PM

- Assist employees in taking control of their career and professional development

All IBM jobs have been grouped into one of several different functional areas, called job families. A job family is a collection of jobs that share similar functions or skills (e.g., managing project risk, apply knowledge of release planning, etc.). If data is not available for a specific job, the responsibilities of the position are compared to the definition of the job family to determine the appropriate job family assignment.

Project managers and, for the most part, program managers fall into the PM job family. PM positions ensure customer requirements are satisfied through the formulation, development, implementation and delivery of solutions. PM professionals are responsible for the overall project plan, budget, work breakdown structure, schedule, deliverables, staffing requirements, managing project execution and risk, and applying PM processes and tools. Individuals are required to manage the efforts of IBM and customer employees as well as third-party vendors to ensure that an integrated solution is provided to meet the customer needs. The job role demands significant knowledge and skills in communication, negotiation, problem solving, and leadership. Specifically, PM professionals need to demonstrate skill in:

- Relationship management skills with their teams, customers, and suppliers

- Technology, industry, or business expertise

- Expertise in methodologies

- Sound business judgment

Guidance is provided to management on classifying, developing, and maintaining the vitality of IBM employees. In the context of the PM profession, vitality is defined as professionals meeting PM skill, knowledge, education, and experience requirements (qualification criteria) as defined by the profession, at or above their current level. Minimum qualification criteria are defined for each career milestone and used as an individual’s business commitments or development objectives, in addition to business unit and individual performance targets.

Skilled project and program management professionals are able to progress along their career paths to positions with more and more responsibility. For those with the right blend of skills and expertise, it is possible to move into program management, project executive, and executive management positions. Growth and progression in the profession are measured by several factors:

- General business and technical knowledge required to be effective in the job role

- PM education and skills to effectively apply this knowledge

- Experience that leverages professional and business-related knowledge and skills on the job

- Contributions to the profession, known as giveback, through activities that enhance the quality and value of the profession to its stakeholders

IBM’s project and program management profession has established an end-to-end process to “quality assure” progress through the PM career path. This process is called “qualification” and it achieves four goals:

- Provides a worldwide mechanism that establishes a standard for maintaining and enhancing IBM’s excellence in project and program management. This standard is based on demonstrated skills, expertise, and success relative to criteria that are unique to the profession

- Ensures that consistent criteria are applied worldwide when evaluating candidates for each profession milestone

- Maximizes customer and marketplace confidence in the consistent quality of IBM PM professionals through the use of sound PM disciplines (i.e., a broad range of project and program management processes, methodologies, tools and techniques applied by PM professionals in IBM)

- Recognizes IBM professionals for their skills and experience

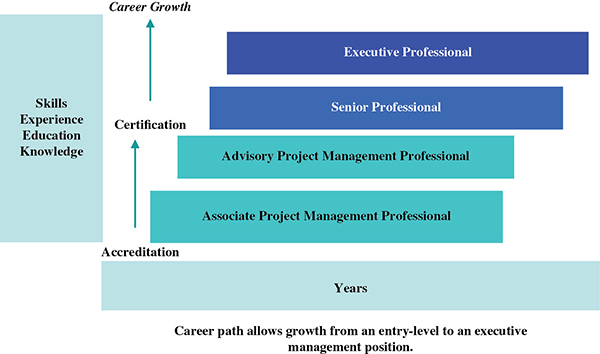

The IBM project and program management profession career path allows employees to grow from an entry level to an executive management position. Professionals enter the profession at different levels depending on their level of maturity in PM. Validation of a professional’s skills and expertise is accomplished through the qualification process. The qualification process is composed of accreditation (at the lower, entry levels), certification (at the higher, experienced levels), recertification (to ensure profession currency), and/or level moves (moving to a higher certification milestone). (See Figure 15-5.)

Figure 15-5. IBM’s Project and Program Management career growth path.

Accreditation is the entry level into the qualification process. It occurs when the profession’s qualification process evaluates a PM professional for associate and advisory milestones.

Certification is the top tier of the qualification process and is intended for the more experienced project or program manager. It occurs when the profession’s qualification process evaluates a PM professional for senior and executive project management milestones. These milestones require a more formal certification package to be completed by the project manager. The manager authorizes submission of the candidate’s package to the Project Management Certification Board. The IBM Project Management Certification Board, comprised of profession experts, administers the authentication step in the certification process. The board verifies that the achievements documented and approved in the candidate’s certification package are valid and authentic. Once the board validates that the milestones were achieved, the candidate becomes certified as a senior or executive PM.

Recertification evaluates IBM certified PM professionals for currency at senior and executive PM milestones. Recertification occurs on a three-year cycle and requires preparing a milestone package in which a project manager documents what he/she has done in PM, continuing education, and giveback since the previous validation cycle.

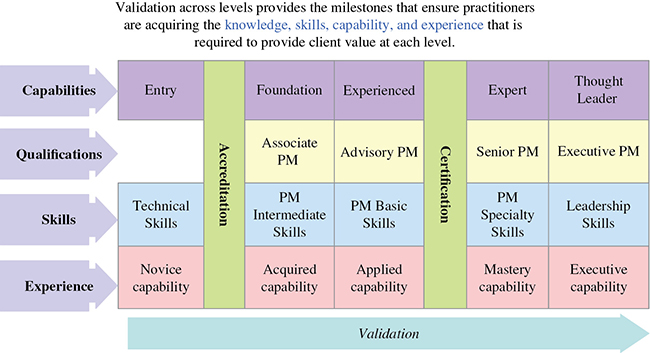

IBM continues to be committed to improving its PM capabilities by growing and supporting a robust, qualified PM profession and by providing quality PM education and training to its practitioners (see Figure 15-6).

Figure 15-6. Career framework validation

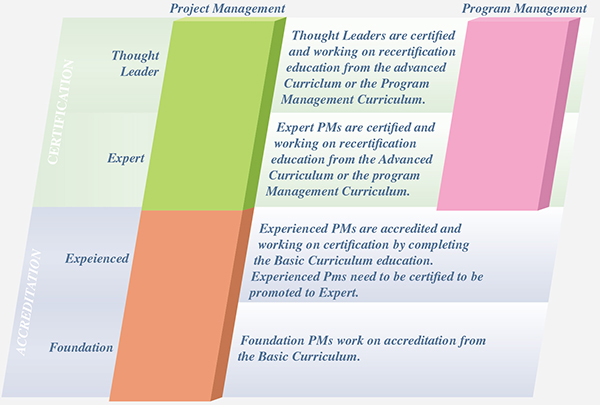

Equally important to project manager development and certification is a refinement of the process by which project managers are assigned. Projects are assessed based on size, revenue implications, risk, customer significance, time urgency, market necessity, and other characteristics; certified project managers are assigned to them based on required education and experience factors (see Figure 15-7).

Figure 15-7. The Refinement Process

Guidance is provided to management on classifying, developing, and maintaining the vitality of IBM employees. In the context of the PM profession, vitality is defined as professionals meeting PM skill, knowledge, education, and experience requirements (qualification criteria) as defined by the profession, at or above their current level. Minimum qualification criteria are defined for each career milestone and used as individual’s business commitments or development objectives, in addition to business unit and individual performance targets.

The PM CoE is chartered to increase Practitioner Competency in project and program management across IBM. This includes worldwide leadership of IBM’s PM profession, its Managing Projects and Programs validation processes, and IBM’s relationship with PMI, as well as project and program management skills development through education and mentoring. A global team works to cultivate this project and program management expertise and to maintain standards of excellence within the PM profession.

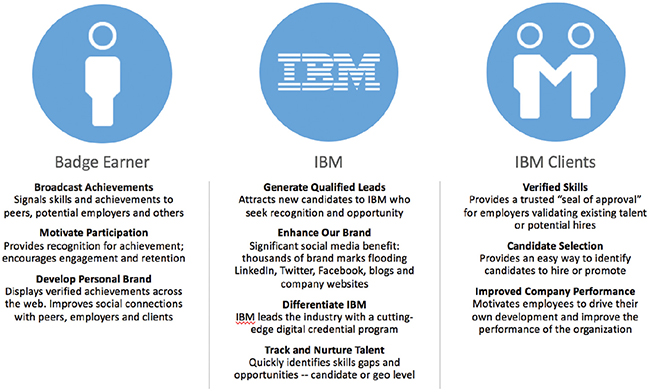

Digital Credentials for the IBM Project Management Profession

IBM is one of the early adopters of the Open Badges initiative. For those not familiar with Open Badges, they are digital emblems that symbolize skills and achievements. A badge contains metadata with skills tags and accomplishments. It is easy to share in social media such as LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, and blogs. Badges help IBM to validate and verify achievements and are based on Mozilla’s Open Badges standard.

IBM sees the Open Badge initiative as a means to:

- Differentiate IBM, increase our pool of talent, provide continuous engagement and progression

- Provide instant recognition by capturing a complete skills profile, from structured training to code building

- Provide IBM customers and best practices (BPs) with verified skills data on employees and potential hires

IBM sees benefits in this program for both the Badge Earner, clients, and the company itself. (See Figure 15-8.)

Figure 15-8. How IBM sees the Badge Earner, itself, and its clients.

Figure 15-9. IBM badges.

Within IBM, the PM profession has been one of the early adopters and has developed four badges (Figure 19–9) to recognize PM and program management skills and experience, based on the IBM PM career requirements. Each professional enters the PM profession at different capability levels depending on years of experience, skills, capabilities, and knowledge of PM. Qualification of a professional’s skills, capabilities, and expertise is completed through the validation process.

In 2016, the PM profession recognized all employees who have achieved one of those levels in their IBM career.

PM badges were very well received with a 95 percent positive comments on the recognition and a strong uptake in claiming badges.

This initiative has further motivated project managers to continue their professional careers at IBM. In addition, managers of project managers, who with the support of the PM/CoE, can recognize employees expertise and the badging program is another mechanism motivate employees to increase their skills and experience by following the Project

Knowledge Sharing

The PM Knowledge Network (PMKN) supports IBM’s becoming a project-based enterprise by leveraging knowledge through sharing and reusing assets (intellectual capital). The PMKN repository supports the PMKN Community with a wide range of assets that include templates, examples, case studies, forms, white papers, and presentations on all aspects of PM. Practitioners may browse, download, or reuse any of the more than 2716 entries to aid their projects, their proposals, or their understanding.

According to Orla Stefanazzi, PMP®, Communications Manager, the IBM PM CoE has driven a strong sense of community for its global PM professionals; this is a best practice among IBM’s professions.

Within IBM, a community is defined as a collection of professionals who share a particular interest, work within a knowledge domain, and participate in activities that are mutually beneficial to building and sustaining performance capabilities. Our community focuses on its members and creating opportunities for members to find meaning in their work, increase their knowledge and mastery of a subject area, and feel a sense of membership—that they have resources for getting help, information, and support in their work lives. Knowledge sharing and intellectual capital reuse are an important part of what a community enables but not the only focus. Communities provide value to the business by reducing attrition, reducing the speed of closing sales, and by stimulating innovation.

Communities are part of the organizational fabric but not defined or constrained by organizational boundaries. In fact, communities create a channel for knowledge to cross boundaries created by workflow, geographies, and time and in so doing strengthen the social fabric of the organization. They provide the means to move local know-how to collective information, and to disperse collective information back to local know-how. Membership is totally based on interest in a subject matter and is voluntary. A community is NOT limited by a practice, a knowledge network, or any other organizational construct.

The PM Knowledge Network (PMKN) Community is sponsored by the IBM PM/COE. Membership is open to all IBM employees with a professional career path or an interest in PM. The PMKN is a self-sustaining community of practice with over 40,000 members who come together for the overall enhancement of the profession. Members share knowledge and create PM intellectual capital. The PMKN offers an environment to share experiences and network with fellow project managers. Members receive communications relevant to the PM profession to enable them to deliver successful projects and programs in areas such as:

- Information on weekly PMKN eSharenet sessions. These sessions provide the global PM community with informal one-hour education on a range of topics that are aligned to IBM’s strategy (e.g., agile, benefits realization). These sessions are delivered by a range of internal and external speakers who are recognized subject matter experts in their field. The majority of these sessions enable IBM’s global project managers to claim 1 personal development unit (PDU) as part of the PMI recertification requirements.

- Project Management Community news items.

- Focused communications to assist the global PM community in developing their skills and PM career.

The global PM community is encouraged to be “socially eminent” by utilizing the forums to post questions and engage on PM topics of interest, creating blogs to share information and insights with other project managers, and being active community members.

Upon entering the PM community, professional hires into IBM are often asked the question: “What is the biggest cultural difference you have found in IBM compared to the other companies in which you have worked?” The most common answer is that their peers are extremely helpful and are willing to share information, resources and help with job assignments. The culture of IBM lends itself graciously to mentoring. As giveback is a requirement for certification, acting as a mentor to candidates pursuing certification not only meets a professional requirement but also contributes to the community.

To address communication requirements of the global PM community in IBM the primary channels include the PM/COE website and focused biweekly newsletters, as well as via the PMKN Community. Project management can even be added into a project manager’s corporate Web profile. However, as the PM profession grows so do the requirements for projects targeted at specific communities. The PM CoE has developed the following subcommunities (referred to as communities of practice (CoPs)) to provide focused information:

- Project managers who are new to the profession

- Managers of project managers

- Local geography PM communities

- Social PM

- IBM Program Work Center

- PM Office

- PM Method

- PM Maturity

- Agile @IBM

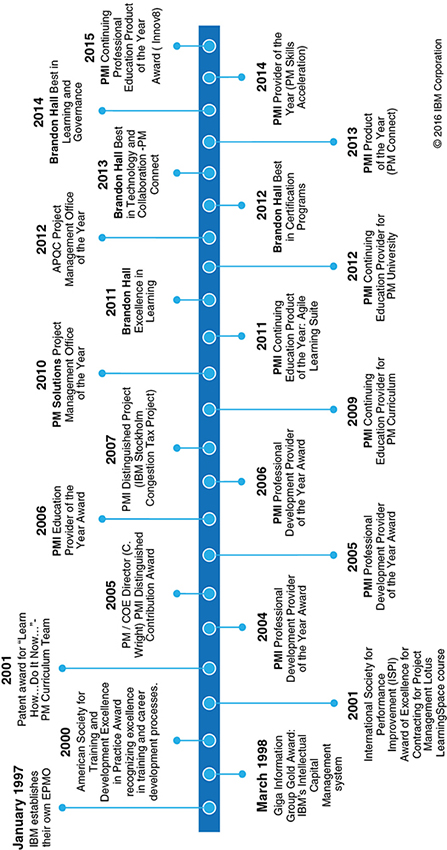

But IBM’s best practices are not just recognized within the company. Many have received recognition from industry sources. (See Figure 15-10.)

Figure 15-10. IBM best practices.

Challenges and Opportunities

As our transformation journey and the rate of change across industries continues, there are a number of fundamental questions we are asking ourselves in the PMCOE to ensure we maintain relevance and ensure our project managers continue to excel at what they do.

- How do we address the complexity questions posed earlier in this chapter?

- Do our methods, processes, and tools need to be customized to meet each of the complexity criteria, or can we deliver a one-size-fits-all solution to support out PM community?

- As complexity increases, how do we simplify the role of the project managers and allow them to focus on value-add activities?

- In an ever-challenging environment where resources are scarce and costs are under continuous focus, how do we automate more and eliminate redundant tasks?

The PMCOE is tacking these challenges. We know that one size does not fit all.

For example, agile is becoming more and more prevalent both in IBM and in the marketplace; however, it is not going to be a panacea solution for all projects. We need to help our project managers pick the right method for a particular project by continuing to provide solutions across a number of different methods and assisting them in choosing the appropriate method and approach.

Through targeted education and tailored solutions, we are addressing other complexity factors, such as industry, technology, and client-specific ones.

One example is a self-learning cognitive engine to sit on top of our knowledge repositories. Our project managers will have an interactive portal whereby they can search and locate the most relevant information to suit their requirement—text, video, and so on. This cognitive assistant will interpret the questions asked and answers provided to continuously enhance its capabilities, freeing up the project manager to focus on tasks that add business value.

Another example—we will deploy a predictive engine that will be able to inspect hundreds of project attributes and highlight “potential future trouble spots” based on thousands of data points from a vast database of previous projects.

15.2 CITIGROUP, INC.3

At Citi, we view project management (PM) as a critical area of strength in our ability to manage a global organization. To that end, we have cultivated a PM community to provide opportunities for practitioners to develop their knowledge and network across the company.

Many PM practitioners work in an environment in which much of their regular day is driven by a need to comply with top-down policies, standards, and procedures. Adherence to these and other requirements is compulsory for project completion and corporate compliance.

In the daily drive to comply with requirements, formal opportunities may not exist for these practitioners (project managers or others who are leading projects) to learn from others, share experiences, or deepen/round out their skill sets. In such intense environments, practitioners may not fully benefit from the talents and institutional knowledge that exist across the enterprise.

Building a Community of Practitioners

Personal leadership skills, and network building, are critical to project success.

PM and business analysis are two areas of practice in which natural opportunities exist to build robust communities of practitioners. The community is a place in which people with common roles, or who are performing similar tasks, can self-identify.

Being part of a community creates a sense of purpose, of being a part of something greater, and can create pride in one’s practice.

The community becomes the platform that can help to drive learning, collaboration and knowledge sharing. It provides opportunities for networking not only from within but also access to external sources. It can provide opportunities for skills development. It is a place where the many generations working in the organization or in similar roles can meet and share viewpoints. It is a vehicle to gather, guide, and possibly respond to the prevailing concerns of the group.

The Citi Program Management Council

The Citi Program Management Council (CPMC) was formed in support of the institutional practices of program management and PM at Citigroup, Inc. A chartered, global organization that spans the entire enterprise, the CPMC is accountable to the executive level of the company. The CPMC Executive Committee’s representation at the top of the house shows the organizational commitment of Citigroup to PM and program management.

PM is recognized as fundamental to the successful delivery of Citi’s work efforts.

The CPMC defines and sets PM policy and standards at Citi. Task forces, led by employees of Citi’s Global Program Management Office, execute the CPMC’s governance responsibilities.

The task forces include Project Management (PM) Governance and Standards, PM Data and Reporting, Enterprise Process Quality Assurance, PM Tools, and PM and Business Analysis (BA) Capabilities. These task forces are involved throughout Citi in multiple capacities each day, working with teams across the organization to manage activities vital to the growth and success of PM at Citi. They also ensure that our most vital programs and projects are managed in compliance with regulatory requirements.

Cultivating Community to Foster Success

PM is central to our business: It is practiced enterprise-wide. The CPMC drives PM to be a core competency in the organization, striving to promote a common language, understanding, and expectation.

The PM and BA Capabilities task forces are responsible for nurturing this competency in the organization. One way in which this is accomplished is by creating and fostering the communities for those practicing PM and related disciplines (such as BA).

Cultivating these communities and growing them in the organization enables us to develop a support and education network for our PM and BA resources, as well as those within the organization learning these competencies.

Citi’s networks of project managers and business analysts consist of employees throughout the firm, who are in PM or BA job families, or who have joined because of an interest in PM or BA.

Building PM as a competency, and overseeing these networks, are parts of the core mandate of the Capabilities task forces. They work together to create a holistic environment of connection and engagement, via a variety of means and media, including email, corporate social media, knowledge sharing, and support. Behind each connection is communications and engagement strategy.

Connecting the Community

We connect PM and BA groups to one another and to the organization through a variety of channels and media, as described next.

Social Media

Citigroup leverages a robust enterprise social media platform. The CPMC Capabilities task force uses that platform to engage the organization in collaborative learning and growth.

Sites maintained include a training center, network hubs for project managers and business analysts, and special event management sites.

The CPMC’s free knowledge-sharing sites, including the Citi PM community, are among the most visited in the organization. They are open to nearly all employees and contain information, discussions, and blogs.

Content

Communities thrive on fresh, relevant content. Good content can be shared by leadership and community participants. Content should be regular in frequency, relevant in topic and shareable in this trusted environment.

Here are some of the regular content items that Citi provides:

- PM Network News. A monthly email and online newsletter showcasing CPMC updates, articles on PM and program management, PM Network events, and training

- Targeted email notices. Email messages to specific training audiences when courses are available that meet their training interests or requirements

- Weekly open roles notices. Weekly email message and online posting highlighting job openings in project manager roles to support cross-pollination of talent across the enterprise

- Course information. Up-to-the-minute information on all PM/BA/Agile courses offered on behalf of the CPMC, links to registration, and full course catalogs with descriptions

- Blogs/discussions. Freely interactive platform where people can ask questions and discuss hot topics with anyone in the organization who accesses the community

- Skills assessments. Help trainees assess the appropriate level of training to take

Engagement

Active engagement is a measure of the health of your network. Beyond the items above as part of content, other opportunities to engage community members in shared experiences are important to the care of the community. Some of the engagement opportunities within the Citi community are discussed next.

Programs

- Annual CPMC Excellence Awards. Awards showcasing excellence in project/program management or BA practices and innovations.

- Mentor program. Facilitated by the Capabilities team, a more senior project manager or business analyst is paired with a junior project manager or business analyst; the mentor program creates an avenue for advice sharing, and often results in enduring professional relationships for employees who work on projects.

- Training Roadmaps (PM/BA). The roadmaps provide training and awareness opportunities across Citi to support maturity and acumen in the professional competencies.

- Badging to Increase Engagement. We are rolling out a program in 2017 that awards virtual corporate social media badges to PM Network members. Using a gamification approach, the campaign will help the CPMC to encourage participation and ownership in the drive towards common PM practices at Citi. Our PM practitioners will have the chance to earn badges for participating in custom training programs. In addition, the badges will recognize engagement in communities under the Citi PM umbrella, including participating in mentor programs and other PM community initiatives.

Community Events

- Project Management Awareness Week. CPMC sponsors an annual themed event consisting of virtual and in-person workshops around the globe with free PDUs available for attending sessions. Yearly videos are prepared with senior Citi leaders promoting the PM profession.

- Grows PM community and cements CPMC’s central role

- Networking, best practices, resources for building PM skills

- Targets project managers, business analysts, all interested

- International PM Day/Mini-PM Awareness Week. The CPMC warmly embraces International Project Management Day each November as a celebration to this practice. We also use the opportunity to revisit key topics from our PM Awareness Week held earlier in the year.

- Speaker series. Regular, rotating speaker series events on hot topics such as agile and PMP® exam changes

- Virtual Q&A sessions. Online, WebEx, or phone sessions answering questions about important topics in PM

- Community outreach. Support outreach efforts and foster relationships with key internal and external partner organizations

Conclusion: Care and Feeding of a Core Competency

The CPMC builds PM talent by building the PM community at Citi. We facilitate formal training, but we also provide numerous low- and no-cost options for project managers to improve their knowledge and their resources. We help PMP-certified project managers earn PDUs to maintain their certifications.

The key for us in building this core competency has been to supplement training with community building. By providing training and a community, we demonstrate to our project managers that they are part of a larger organization of practitioners within Citi. We enable project managers to learn the recognized methodologies through training—and to bolster their skills, their experience, and their networks through community.

We believe that as we grow and support this network, we expand the skills of our workforce, create opportunities for growth, and increase employee engagement. Ultimately, the CPMC’s Capabilities task forces not only help to grow the PM competency but to promote the PM profession.

15.3 MICROSOFT CORPORATION

There are training programs that discuss how to develop good methodologies. These programs focus on the use of “proven practices” in methodology development rather than on the use of a single methodology. Microsoft has developed a family of processes that embody the core principles of and proven practices in project management (PM). These processes combined with tools and balancing people are called Microsoft Solutions Framework (MSF).4 The remainder of this section presents just a brief summary of MSF. For more information and a deeper explanation of the topic, please refer to Microsoft Solutions Framework Essentials.5

MSF was created more than 20 years ago, when Microsoft recognized that IT was a key enabler to help businesses work in new ways. Historically, IT had a heritage of problems in delivering solutions. Recognizing this, MSF was created based on Microsoft’s experience in solution delivery.

MSF is more than just PM. MSF is about solutions delivery of which PM (aka governance) is a key component. Successful delivery is balancing solution construction with governance. According to Mike Turner:

At its foundation, MSF is about increasing awareness of the various elements and influences on successful solutions delivery—no one has a methodological silver bullet; it is next to impossible to provide best practice recipes to follow to ensure success in all projects…. MSF is about understanding your environment so you can create a methodology that enables a harmonious balance between managing projects and building solutions.

Another key point with regard to MSF is that project management is seen as a discipline that all must practice, not just the project managers. Everyone needs to be accountable and responsible to manage their own work (i.e., project manager of themselves)—that builds trust among the team (something very needed in projects with Agile-oriented project management), not so much with formally run projects (still very top-down project management).

The main point that MSF tries to get across is that customers and sponsors want solutions delivered—they frankly see project management as a necessary overhead. Everyone needs to understand how to govern themselves, their team and the work that the project does—not just the project managers.

Good frameworks focus on understanding of the need for flexibility. Flexibility is essential because the business environment continuously changes, and this in turn provides new challenges and opportunities. As an example, Microsoft recognizes that today’s business environment has the following characteristics:

- Accelerating rates of change in business and technology

- Shorter product cycles

- Diverse products and services

- New business models

- Rapidly changing requirements

- Legislation and corporate governance

- Growing consumer demand

- New competitive pressures

- Globalization

Typical challenges and opportunities include:

- Escalating business expectations

- Technology is seen as a key enabler in all areas of modern business.

- Increasing business impact of technology solutions

- Risks are higher than ever before.

- Maximizing the use of scarce resources

- Deliver solutions with smaller budgets and less time.

- Rapid technology solutions

- Many new opportunities, but they require new skills and effective teams to take advantage of them.

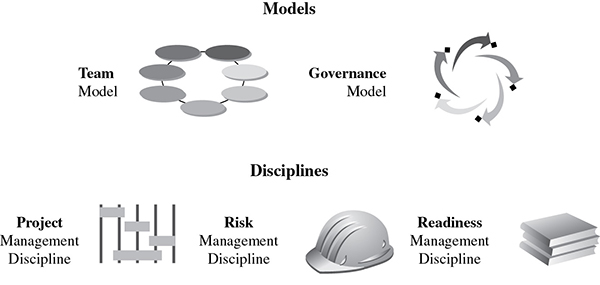

With an understanding of the business environment, challenges and opportunities, Microsoft created MSF.6 MSF is an adaptable framework comprising:

- Models (see Figure 15-11)

- Disciplines (see Figure 15-11)

- Foundation principles

- Mind-sets

- Proven practices

Figure 15-11. MSF models and disciplines.

Source: M. S. V. Turner, Microsoft Solutions Framework Essentials (Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press, 2006). All rights reserved.

MSF is used for successfully delivering solutions faster, requiring fewer people, and involving less risk while enabling higher-quality results. MSF offers guidance in how to organize people and projects to plan, build, and deploy successful technology solutions.

MSF foundation principles guide how the team should work together to deliver the solution. This includes:

- Foster open communications.

- Work toward a shared vision.

- Empower team members.

- Establish clear accountability, shared responsibility.

- Deliver incremental value.

- Stay agile, expect and adapt to change.

- Invest in quality.

- Learn from all experiences.

- Partner with customers.

MSF mind-sets orient the team members on how they should approach solution delivery. Included are:

- Foster a team of peers.

- Focus on business value.

- Keep a solution perspective.

- Take pride in workmanship.

- Learn continuously.

- Internalize qualities of service.

- Practice good citizenship.

- Deliver on your commitments.

With regard to proven practices, Microsoft continuously updates MSF to include current proven practices in solution delivery. All of the MSF courses use two important PM best practices. First, the courses are represented as a framework rather than as a rigid methodology. Frameworks are based on templates, checklists, forms, and guidelines rather than the more rigid policies and procedures. Inflexible processes are one of the root causes of project failure.

The second best practice is that MSF focuses heavily on a balance among people, process, and tools rather than only technology. Effective implementation of PM is a series of good processes with emphasis on people and their working relationships: namely, communication, cooperation, teamwork, and trust. Failure to communicate and work together is another root cause of project failure.

MSF focuses not only on capturing proven practices but also on capturing the right proven practices for the right people. Mike Turner states:

The main thing that I think sets MSF apart is that it seeks to set in place a commonsense, balanced approach to solutions delivery, where effective solutions delivery is an ever changing balance of people, processes and tools. The processes and tools need to be “right sized” for the aptitude and capabilities of the people doing the work. So often “industry best practices” are espoused to people who have little chance to realize the claimed benefits.

MSF espouses the importance of people and teamwork. This includes:

- A team is developed whose members relate to each other as equals.

- Each team member is provided with specific roles and responsibilities.

- The individual members are empowered in their roles.

- All members are held accountable for the success of their roles.

- The project manager strives for consensus-based decision making.

- The project manager gives all team members a stake in the success of the project.

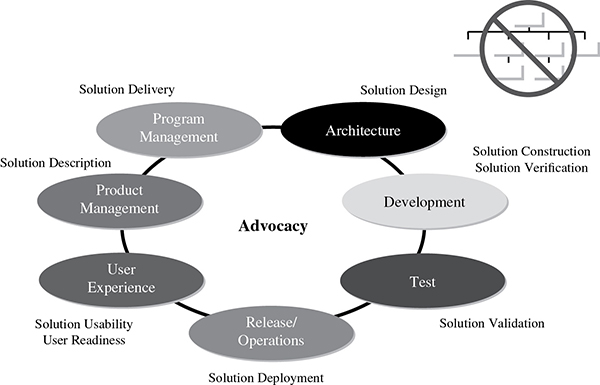

The MSF team model is shown in Figure 15-12. The model defines the functional job categories or skill set required to complete project work as well as the roles and responsibilities of each team member. The team model focuses on a team of collaborating advocates rather than a strong reliance on the organizational structure.

Figure 15-12. MSF team model

Source: M. S. V. Turner, Microsoft Solutions Framework Essentials (Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press). All rights reserved.

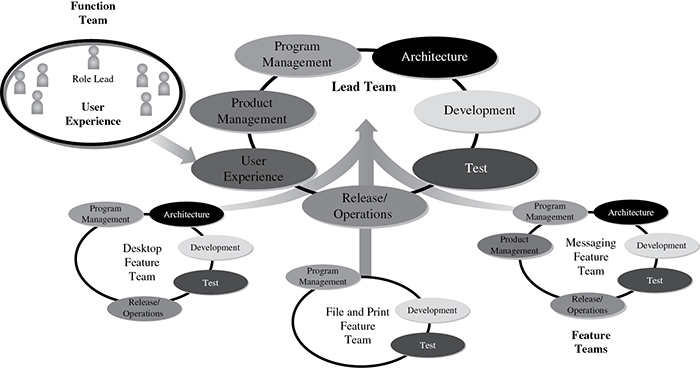

On some projects, there may be the necessity for a team of teams. This is illustrated in Figure 15-13.

Figure 15-13. MSF team of teams.

Source: M. S. V. Turner, Microsoft Solutions Framework Essentials (Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press, 2006). All rights reserved.

Realistic milestones are established and serve as review and synchronization points. Milestones allow the team to evaluate progress and make midcourse corrections where the costs of the corrections are small. Milestones are used to plan and monitor progress as well as to schedule major deliverables. Using milestones benefits projects by:

- Helping to synchronize work elements

- Providing external visibility of progress

- Enabling midcourse corrections

- Focusing reviews on goals and deliverables

- Providing approval points for work being moved forward

There are two types of milestones on some programs: major and interim. Major milestones represent team and customer agreement to proceed from one phase to another. Interim milestones indicate progress within a phase and divide large efforts into workable segments.

For each of the major milestones and phases, Microsoft defines a specific goal and team focus. For example, the goal of the envisioning phase of a program might be to create a high-level review of the project’s goals, constraints, and solution. The team focus for this phase might be to:

- Identify the business problem or opportunity

- Identify the team skills required

- Gather the initial requirements

- Create the approach to solve the problem

- Define goals, assumptions, and constraints

- Establish a basis for review and change

MSF also establishes quality goals for each advocate. This is a necessity because there are natural “opposing” goals to help with quality checks and balances—that way realistic quality is built in the process and not as an afterthought. This is shown in Table 15-1.

TABLE 15-1 QUALITY GOALS AND MSF ADVOCATES

| MSF Advocate | Key Quality Goals |

| Product management | Satisfied stakeholders |

| Program management | Deliver solution within project constraints Coordinate optimization of project constraints |

| Architecture | Design solution within project constraints |

| Development | Build solution to specifications |

| Test | Approve solution for release ensuring all issues are identified and addressed |

| User experience | Maximize solution usability Enhance user effectiveness and readiness |

| Release/operations | Smooth deployment and transition to operations |

Source: M. S. V. Turner, Microsoft Solutions Framework Essentials (Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press). All rights reserved.

It is often said that many programs can go on forever. MSF encourages baselining documents as early as possible but freezing the documents as late as possible. As stated by Mike Turner:

The term “baselining” is a hard one to use without the background or definition. When a team, even if it is a team of one, is assigned work and they think they have successfully completed that work, the milestone/checkpoint status is called “Complete” (e.g., Test Plan Complete); whereas “Baseline” is used when the team that is assigned to verify the work agrees that the work is complete (e.g., Test Plan Baselined). After the Baseline milestone/checkpoint, there is no more planned work. At the point when the work is either shipped or placed under tight change control is when you declare it “Frozen”—meaning any changes must be made via the change control process. This is why you want to put off formal change management as late as possible because of the overhead involved.

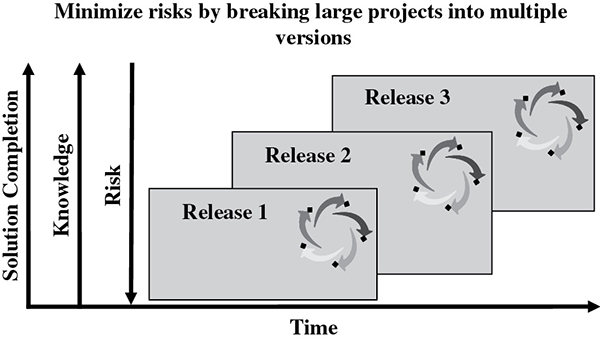

This also requires a structured change control process combined with the use of versioned releases, as shown in Figure 15-14. What the arrows on the left mean is that as the solution is delivered, the solution completion increases, the knowledge of the solution space increases, and the overall risk to solution delivery goes down. The benefits of versioned releases include:

- Forcing closure on project issues

- Setting clear and motivational goals for all team members

- Effective management of uncertainty and change in project scope

- Encouraging continuous and incremental improvement

- Enabling shorter delivery time

Figure 15-14. MSF iterative approach.

Source: M. S. V. Turner, Microsoft Solutions Framework Essentials (Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press). All rights reserved.

One of the strengths of MSF is the existence of templates to help create project deliverables in a timely manner. The templates provided by MSF can be custom-designed to fit the needs of a particular project or organization. Typical templates might include:

- Project schedule template

- Risk factor chart template

- Risk assessment matrix template

- Postmortem template

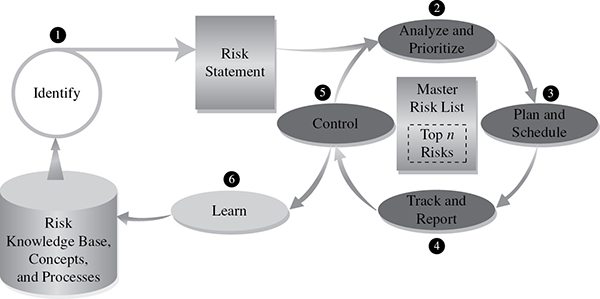

The MSF process for risk management is shown in Figure 15-15. Because of the importance of risk management today, it has become an important component of all PM training programs.

Figure 15-15. MSF risk management process.

Source: M. S. V. Turner, Microsoft Solutions Framework Essentials (Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press). All rights reserved.

MSF encourages all team members to manage risk, not just the project managers. The process is administered by the project manager.

- MSF Risk Management Discipline. A systematic, comprehensive, and flexible approach to handling risk proactively on many levels.

- MSF Risk Management Process. This includes six logical steps: identify, analyze, plan, track, control, and learn.

Some of the key points in the MSF risk approach include:

- Assess risk continuously.

- Manage risk intentionally—establish a process.

- Address root causes, not just symptoms.

- Risk is inherent in every aspect and at all levels of an endeavor.

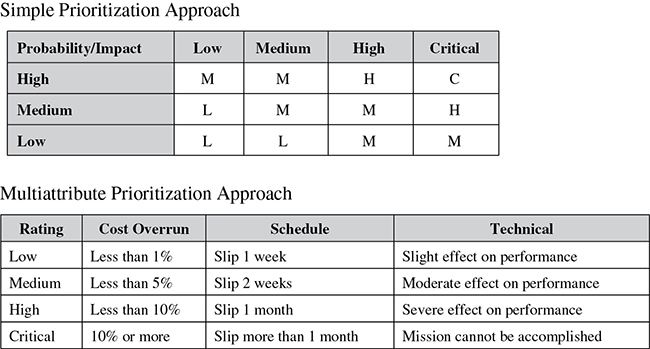

There are numerous ways to handle risk, and MSF provides the team with various options. As an example, Figure 15-16 shows two approaches for risk prioritization.

Figure 15-16. Risk prioritization example.

Source: M. S. V. Turner, Microsoft Solutions Framework Essentials (Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press, 2006). All rights reserved.

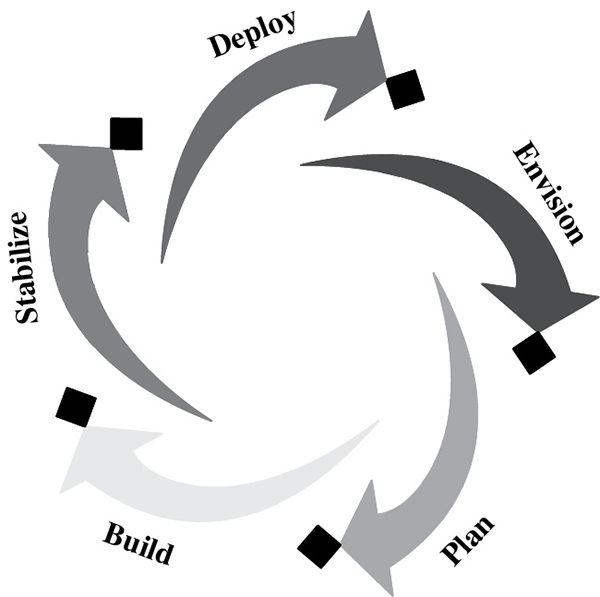

In Figure 15-11, we showed that MSF is structured around a team model and a governance model. The governance model is shown in Figure 15-17. This model appears on all of the MSF figures, illustrating that governance is continuously in place.

Figure 15-17. MSF governance model: enactment tracks.

Source: M. S. V. Turner, Microsoft Solutions Framework Essentials (Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press, 2006). All rights reserved.

There are two components to the MSF governance model: project governance and process enactment:

Project Governance

- Solution delivery process optimization

- Efficient and effective use of project resources

- Ensuring that the project team is and remains aligned with:

- External (strategic) objectives

- Project constraints

- Demand for oversight and regulation

- Process enactment

- Defining, building, and deploying a solution that meets stakeholders’ needs and expectations

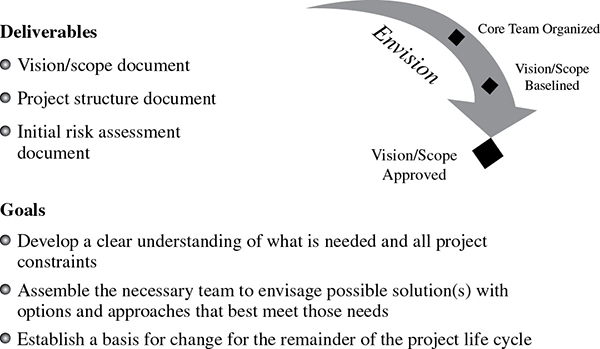

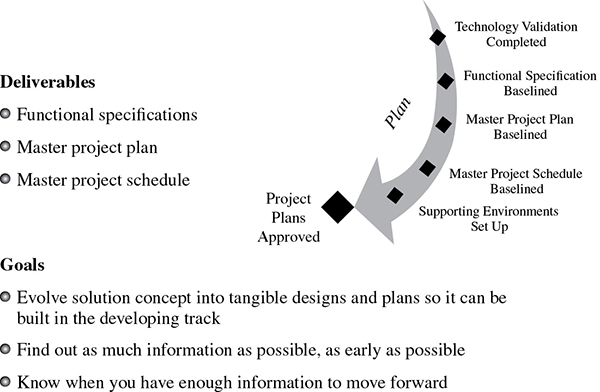

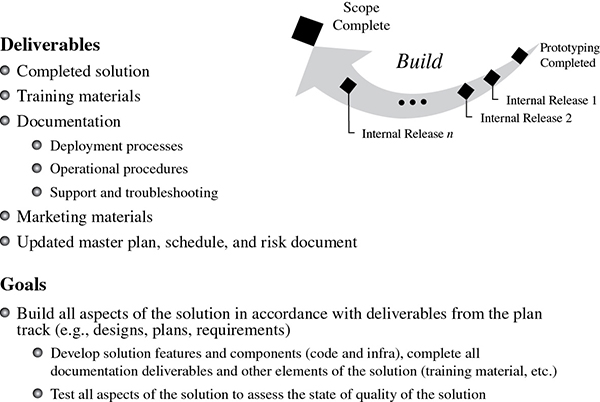

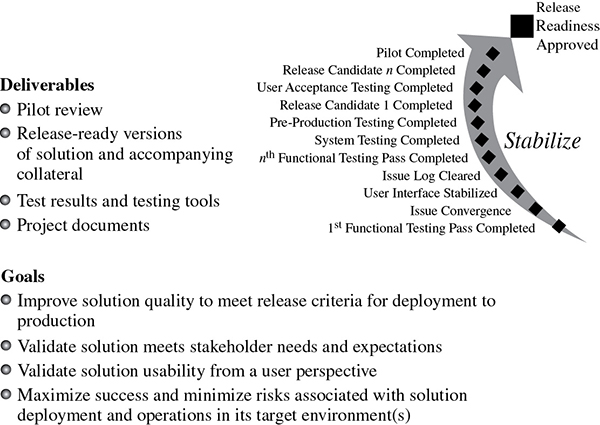

The MSF governance model, as shown in Figure 15-17, is represented by five enactment tracks. Figures 15.18 through 15–22 provide a description of each of the enactment tracks.

Figure 15-18. MSF envision track.

Source: M. S. V. Turner, Microsoft Solutions Framework Essentials (Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press). All rights reserved.

Figure 15-19. MSF plan track.

Source: M. S. V. Turner, Microsoft Solutions Framework Essentials (Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press). All rights reserved.

Figure 15-20. MSF build track.

Source: M. S. V. Turner, Microsoft Solutions Framework Essentials (Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press). All rights reserved.

Figure 15-21. MSF stabilize track.

Source: M. S. V. Turner, Microsoft Solutions Framework Essentials (Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press). All rights reserved.

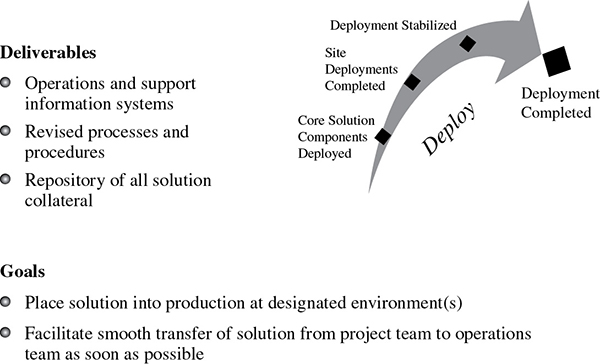

Figure 15-22. MSF deploy track.

Source: M. S. V. Turner, Microsoft Solutions Framework Essentials (Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press). All rights reserved.

MSF has established success criteria for each of the tracks, as described next.

Envision Track

- Agreement by the stakeholders and team has been obtained on:

- Motivation for the project

- Vision of the solution

- Scope of the solution

- Solution concept

- Project team and structure

- Constraints and goals have been identified.

- Initial risk assessment has been done.

- Change control and configuration management processes have been established.

- Formal approval has been given by the sponsors/and or key stakeholders.

Plan Track

- Agreement with stakeholders and team has been obtained on:

- Solution components to be delivered

- Key project checkpoint dates

- How the solution will be built

- Supporting environments have been constructed.

- Change control and configuration management processes are working smoothly.

- Risk assessments have been updated.

- All designs, plans, and schedules can be tracked back to their origins in the functional specifications and the functional specification can be tracked back to envisioning track deliverables.

- Sponsor(s) and/or key stakeholders have signed off.

Build Track

- All solutions are built and complete, meaning:

- There are no additional development of features or capabilities.

- Solution operates as specified.

- All that remains is to stabilize what has been built.

- All documentation is drafted.

Stabilize Track

- All elements are ready for release.

- Operations approval for release has been obtained.

- Business sign-off has been obtained.

Deploy Track

- Solution is completely deployed and operationally stable.

- All site owners signed off that their deployments were successful.

- Operations and support teams have assumed full responsibility and are fully capable of performing their duties.

- Operational and support processes and procedures as well as supporting systems are operationally stable.

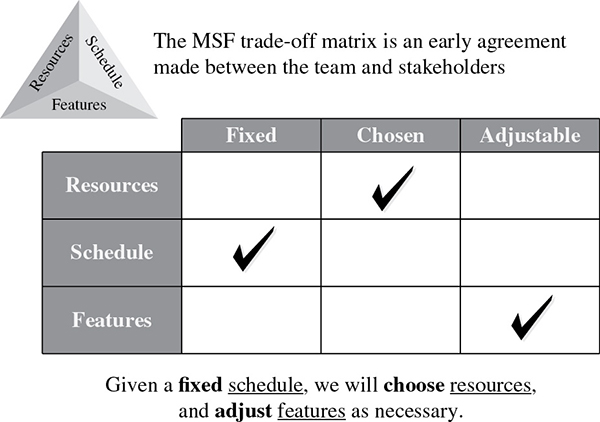

MSF focuses on proactive planning rather than reactive planning. Agreements between the team and the various stakeholder groups early on in the project can make trade-offs easier, reduce schedule delays, and eliminate the need for a reduction in functionality to meet the project’s constraints. This is shown in Figure 15-23.

Figure 15-23. Project trade-off matrix.

Source: M. S. V. Turner, Microsoft Solutions Framework Essentials (Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press, 2006). All rights reserved.

15.4 DELOITTE: ENTERPRISE PROGRAM MANAGEMENT7

Introduction

Many organizations initiate more projects than they have the capacity to deliver. As a result, they typically have too much to do and not enough time or resources to do it. The intended benefits of many projects are frequently not realized, and the desired results are seldom fully achieved.

There are several factors that can make delivering predictable project results that much more difficult:

- Added complexity of the transformational nature of many projects

- Constant drive for improved efficiency and effectiveness

- Renewed pressures to demonstrate accountability and transparency

- Accelerating pace of change and constantly shifting priorities

Traditional methods of coordinating and managing projects are becoming ineffective and can lead to duplication of effort, omission of specific activities, or poor alignment and prioritization with business strategy. Making the right investment decisions, maximizing the use of available resources, and realizing the expected benefits to drive organizational value have never been more important.

This section explores Deloitte’s project portfolio management methods, techniques, approaches, and tools ranging from translating organizational strategy into an aligned set of programs and projects, to tracking the attainment of the expected value and results of undertaken transformational initiatives.

Enterprise Program Management

Organizations are facing increased pressures to “do more with less.” They need to balance rising expectations for improved quality, ease of access, and speed of delivery with renewed pressures to demonstrate effectiveness and cost efficiency. The traditional balance between managing the business (i.e., day-to-day operations) and transforming the business (i.e., projects and change initiatives) is shifting. For many organizations, the proportion of resources deployed on projects and programs has increased enormously in recent years. However, the development of organizational capabilities, structures, and processes to manage and control these investments continues to be a struggle.

Furthermore, there has been a significant increase in project interdependency and complexity. While many projects and programs likely were confined to a specific function or business area in the past, increasingly we see that there are strong systemic relationships between specific initiatives. Most issues do not exist in isolation and resolutions have links and knock-on impacts beyond the scope of one problem. Not only do projects increasingly span people, process, and technology, but they also cross functional, geographical, and often organizational boundaries. Without a structured approach to their deployment, projects and programs can fail to deliver the expected value. The need for strategic approach to project, program, and portfolio management is great.

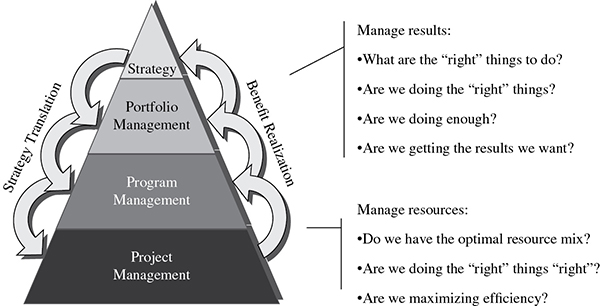

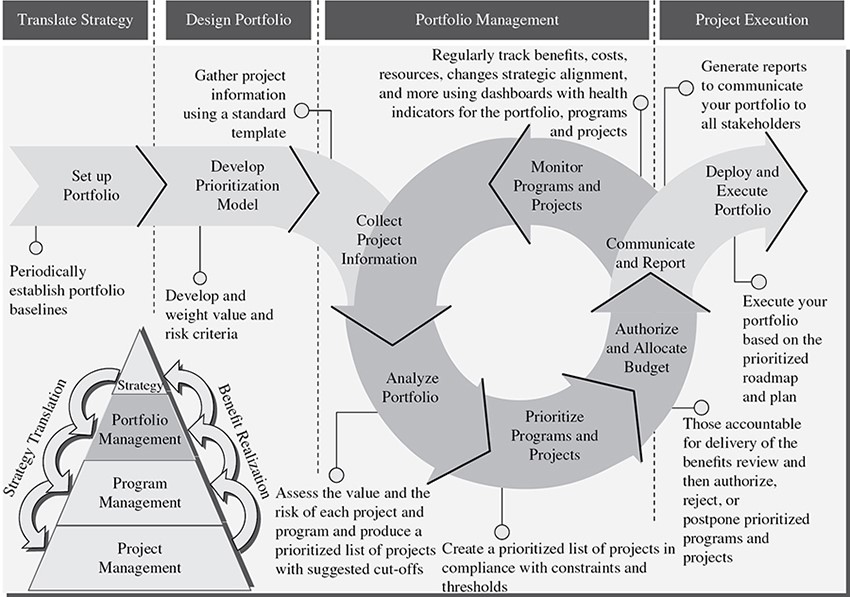

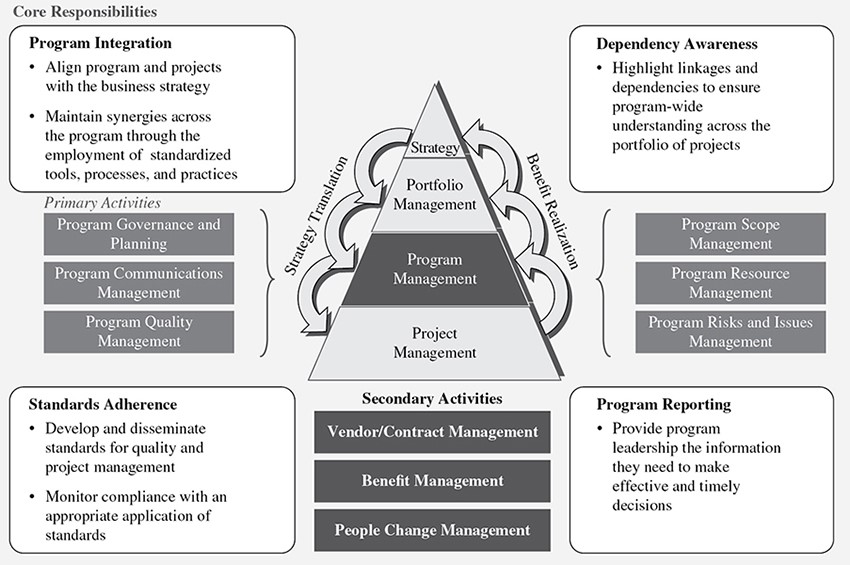

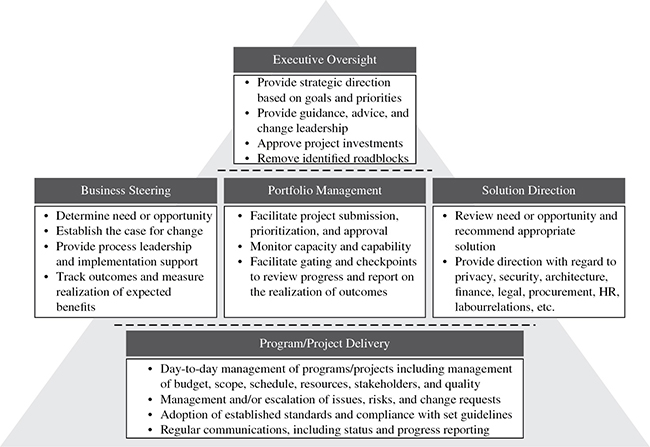

Deloitte’s approach to project portfolio management is represented by the guiding Enterprise Program Management (EPM) framework that provides a model within which projects, programs and portfolios fit into a hierarchy where project execution and program delivery is aligned with enterprise strategy and can lead to improved realization of desired benefits. This approach aims to strike a balance between management of results (effectiveness) and management of resources (efficiency) to deliver enterprise value.

In Figure 15-24, Strategy includes the definition of the organization’s vision and mission, as well as the development of strategic goals, objectives and performance measures. The Portfolio Management capability translates the organization’s enterprise strategy into reality and manages the portfolio to determine effective program alignment, resource allocation, and benefits realization. Program Management focuses on structuring and coordinating individual projects into related sets to determine realization of value that may likely not have been attained by delivering each project independently in isolation. Disciplined Project Management helps enable that defined scope of work packages are delivered to the desired quality standards.

Figure 15-24. Deloitte Enterprise Program Management Framework.

Source: © Deloitte & Touche LLP and affiliated entities.

Strategy and Enterprise Value

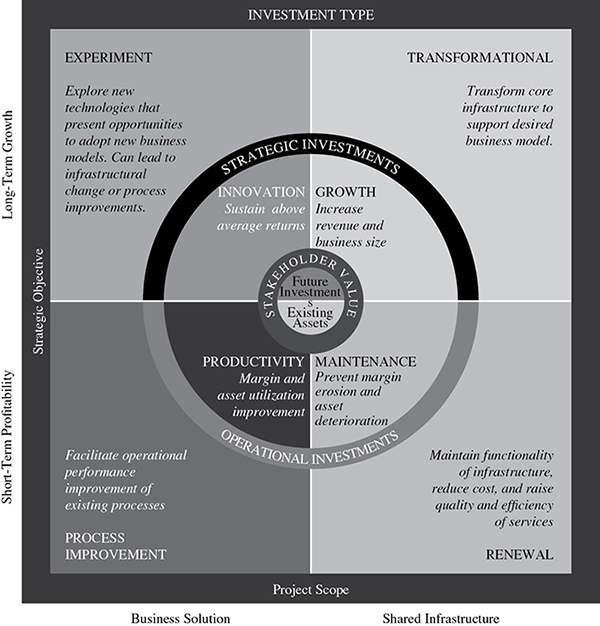

Today’s business leaders live in a world of perpetual motion, running and improving their enterprises at the same time. Tough decisions need to be made every day—setting directions, allocating budgets, and launching new initiatives—all to improve organizational performance and, ultimately, create and provide value for stakeholders. It is easy to say stakeholder value is important, though it is much more difficult to make it influence the decisions that are made every day: where to spend time and resources, how best to get things done, and, ultimately, how to win in the competitive marketplace or in the public sector and effectively deliver a given mandate.

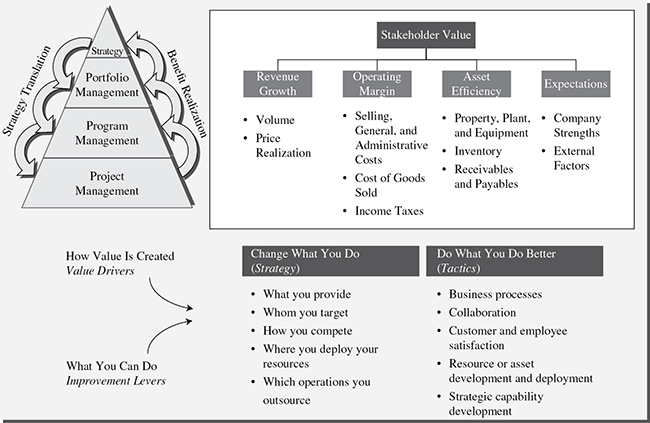

Supporting the Strategy component of the EPM framework, Deloitte’s Enterprise Value Map™ is designed to accelerate the connection between taking action and generating enterprise value. It facilitates the process of focusing on important areas, identifying practical ways to get things done, and determining if chosen initiatives provide their intended business value. The Enterprise Value Map™ can make this process easier by accelerating the identification of potential improvement initiatives and depicting how each can contribute to greater stakeholder value.

The Enterprise Value Map™, as illustrated at a summary level in Figure 15-25, is powerful and appealing because it strikes a very useful and practical balance between:

- Strategy and tactics

- What can be done and how it can be done

- The income statement and the balance sheet

- Organizational capability and operational execution

- Current performance and future performance

Figure 15-25. Deloitte Enterprise Value Map™ (EVM).

Source: © Deloitte & Touche LLP and affiliated entities.

Overall, the Enterprise Value Map™ helps organizations focus on the applicable things and serves as a graphic reminder of what they are doing and why. From an executive perspective, the Enterprise Value Map™ is a framework depicting the relationship between the metrics by which companies are evaluated and the means by which companies can improve those metrics. From a functional perspective, the Enterprise Value Map™ is a one-page summary of what companies do, why they do it, and how they can do it better. It serves as a powerful discussion framework because it can help companies focus on the issues that matter most to them.

The Enterprise Value Map™ is leveraged by Deloitte to help clients:

- Identify things that can be done to improve stakeholder value

- Add structure to the prioritization of potential improvement initiatives

- Evaluate and communicate the context and value of specific initiatives

- Provide insights regarding the organization’s current business performance

- Depict how portfolio of project and programs aligns with the drivers of value

- Identify pain points and potential improvement areas

- Depict past, current, and future initiatives

Stakeholder value is driven by four basic “value drivers”: revenue growth, operating margin, asset efficiency, and expectations:

- Revenue growth. Growth in the company’s “top line,” or payments received from customers in exchange for the company’s products and services.

- Operating margin. The portion of revenues that is left over after the costs of providing goods and services are subtracted. An important measure of operational efficiency.

- Asset efficiency. The value of assets used in running the business relative to its current level of revenues. An important measure of investment efficiency.

- Expectations. The confidence stakeholders and analysts have in the company’s ability to perform well in the future. An important measure of investor confidence.

There are literally thousands of actions companies can take to improve their stakeholder value performance, and the Enterprise Value Map™, in its full version, depicts several hundred of them. While the actions are quite diverse, the vast majority of them revolve around one of three objectives:

- Improve the effectiveness or efficiency of a business process

- Increase the productivity of a capital asset

- Develop or strengthen a company capability

The individual actions in the Value Map start to identify how a company can make those improvements. Broadly speaking, there are two basic approaches to improvement:

- Change what you do (change your strategy). These actions address strategic changes—altering competitive strategies, changing the products and services you provide and to whom, and changing the assignment of operational processes to internal and external teams.

- Do the things you do better (improve your tactics). These actions address tactical changes—assigning processes to different internal or external groups (or channels), redesigning core business processes, and improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the resources executing those processes.

Portfolio Management

Portfolio Management is a structured and disciplined approach to achieving strategic goals and objectives by choosing the most effective investments for the organization, and determining the realization of their combined benefits and value while requiring the use of available resources.

The Portfolio Management function provides the centralized oversight of one or more portfolios and involves identifying, selecting, prioritizing, assessing, authorizing, managing, and controlling projects, programs, and other related work to achieve specific strategic goals and objectives. Adoption of a strategic approach to Portfolio Management enables organizations to improve the link between strategy and execution. It helps them to set priorities, gauge their capacity to provide and monitor achievement of project outcomes to drive the creation and delivery of enterprise value.

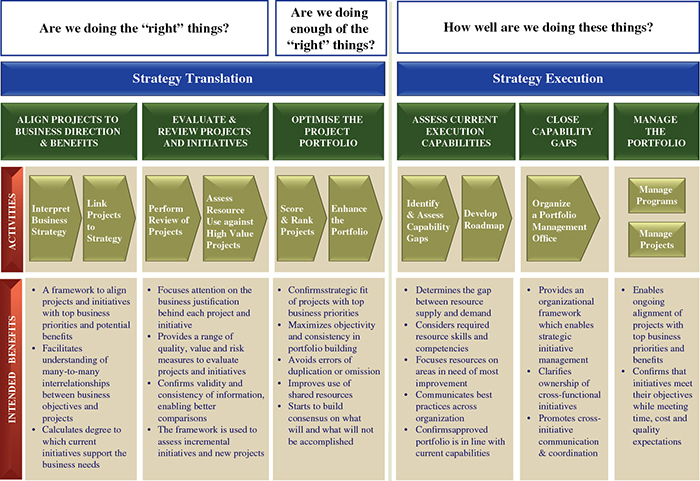

Deloitte’s approach to Portfolio Management can enable an organization to link its strategic vision with its portfolio of initiatives and manage initiatives as they progress. It provides the critical link that translates strategy into operational achievements. As illustrated in Figure 15-26, the Portfolio Management Framework helps to answer these questions: “Are we doing the ‘right’ things?,” “Are we doing enough of the ‘right’ things?,” and “How well are we doing these things?”

Figure 15-26. Deloitte Portfolio Management Framework.

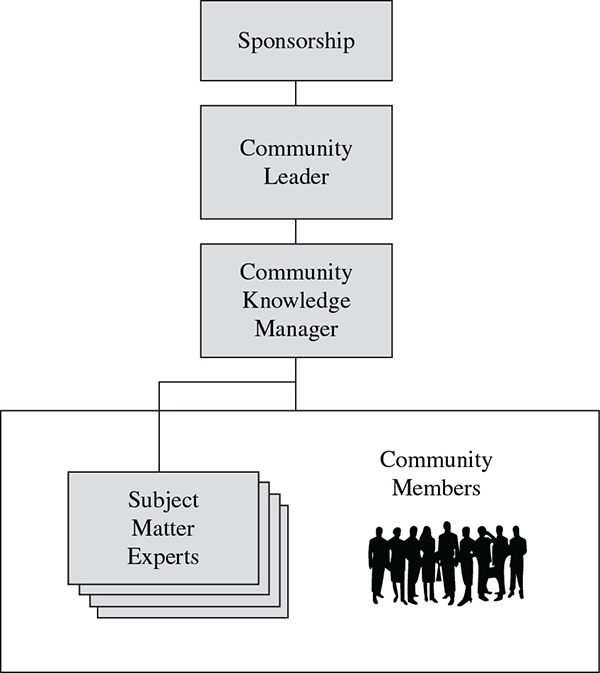

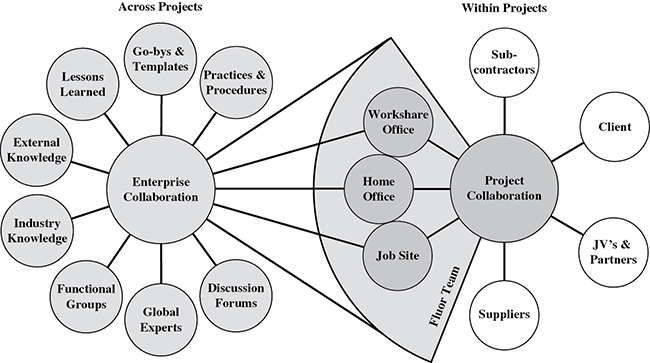

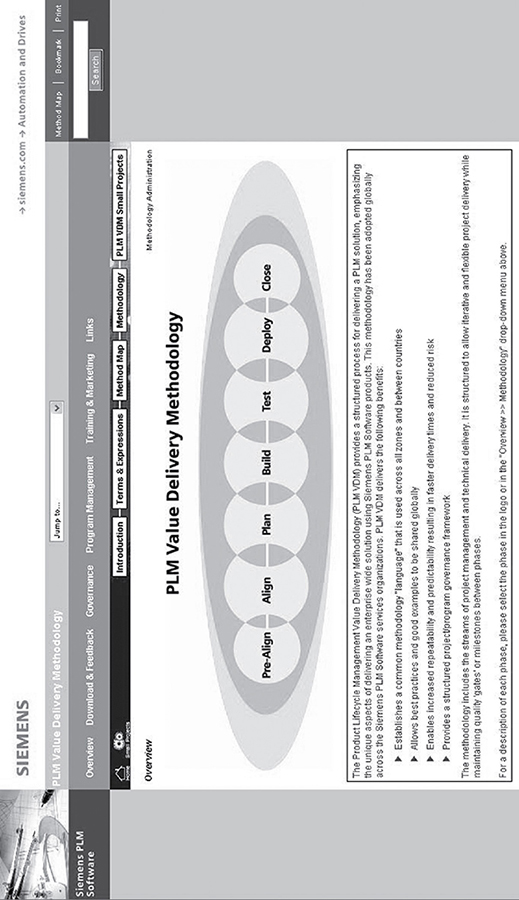

Source: © Deloitte & Touche LLP and affiliated entities.