10

Behavioral Excellence

10.0 INTRODUCTION

Previously, we saw that companies excellent in project management strongly emphasize training for behavioral skills. In the past it was thought that project failures were due primarily to poor planning, inaccurate estimating, inefficient scheduling, and lack of cost control. Today, excellent companies realize that project failures have more to do with behavioral shortcomings—poor employee morale, negative human relations, low productivity, and lack of commitment.

This chapter discusses these human factors in the context of situational leadership and conflict resolution. It also provides information on staffing issues in project management. Finally, the chapter offers advice on how to achieve behavioral excellence.

10.1 SITUATIONAL LEADERSHIP

As project management has begun to emphasize behavioral management over technical management, situational leadership has also received more attention. The average size of projects has grown, and so has the size of project teams. Process integration and effective interpersonal relations have also taken on more importance as project teams have gotten larger. Project managers now need to be able to talk with many different functions and departments. There is a contemporary project management proverb that goes something like this: “When researcher talks to researcher, there is 100 percent understanding. When researcher talks to manufacturing, there is 50 percent understanding. When researcher talks to sales, there is zero percent understanding. But the project manager talks to all of them.”

Randy Coleman, former senior vice president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, emphasizes the importance of tolerance:

The single most important characteristic necessary in successful project management is tolerance: tolerance of external events and tolerance of people’s personalities. Generally, there are two groups here at the Fed—lifers and drifters. You have to handle the two groups differently, but at the same time you have to treat them similarly. You have to bend somewhat for the independents (younger drifters) who have good creative ideas and whom you want to keep, particularly those who take risks. You have to acknowledge that you have some trade-offs to deal with.

A senior project manager in an international accounting firm states how his own leadership style has changed from a traditional to a situational leadership style since becoming a project manager:

I used to think that there was a certain approach that was best for leadership, but experience has taught me that leadership and personality go together. What works for one person won’t work for others. So you must understand enough about the structure of projects and people and then adopt a leadership style that suits your personality so that it comes across as being natural and genuine. It’s a blending of a person’s experience and personality with his or her style of leadership.

Many companies start applying project management without understanding the fundamental behavioral differences between project managers and line managers. If we assume that the line manager is not also functioning as the project manager, here are the behavioral differences:

- Project managers have to deal with multiple reporting relationships. Line managers report up a single chain of command.

- Project managers have very little real authority. Line managers hold a great deal of authority by virtue of their titles.

- Project managers often provide no input into employee performance reviews. Line managers provide formal input into the performance reviews of their direct reports.

- Project managers are not always on the management compensation ladder. Line managers always are.

- The project manager’s position may be temporary. The line manager’s position is permanent.

- Project managers sometimes are a lower grade level than the project team members. Line managers usually are paid at a higher grade level than their subordinates.

Several years ago, when what is now AT&T Ohio, then known as Ohio Bell, was still a subsidiary of American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T), a trainer was hired to conduct a three-day course on project management. During the customization process, the trainer was asked to emphasize planning, scheduling, and controlling and not to bother with the behavioral aspects of project management. At that time, AT&T offered a course on how to become a line supervisor that all of the seminar participants had already taken. In the discussion that followed between the trainer and the course content designers, it became apparent that leadership, motivation, and conflict resolution were being taught from a superior-to-subordinate point of view in AT&T’s course. When the course content designers realized from the discussion that project managers provide leadership, motivation, and conflict resolution to employees who do not report directly to them, the trainer was allowed to include project management–related behavioral topics in the seminar.

Organizations must recognize the importance of behavioral factors in working relationships. When they do, they come to understand that project managers should be hired for their overall project management competency, not for their technical knowledge alone. Brian Vannoni, formerly site training manager and principal process engineer at GE Plastics, described his organization’s approach to selecting project managers:

The selection process for getting people involved as project managers is based primarily on their behavioral skills and their skills and abilities as leaders with regard to the other aspects of project management. Some of the professional and full-time project managers have taken senior engineers under their wing, coached and mentored them, so that they learn and pick up the other aspects of project management. But the primary skills that we are looking for are, in fact, the leadership skills.

Project managers who have strong behavioral skills are more likely to involve their teams in decision making, and shared decision making is one of the hallmarks of successful project management. Today, project managers are more managers of people than they are managers of technology. According to Robert Hershock, former vice president at 3M:

The trust, respect, and especially the communications are very, very important. But I think one thing that we have to keep in mind is that a team leader isn’t managing technology; he or she is managing people. If you manage the people correctly, the people will manage the technology.

In addition, behaviorally oriented project managers are more likely to delegate responsibility to team members than technically strong project managers. In 1996, Frank Jackson, formerly a senior manager at MCI, said:

Team leaders need to have a focus and a commitment to an ultimate objective. You definitely have to have accountability for your team and the outcome of your team. You’ve got to be able to share the decision making. You can’t single out yourself as the exclusive holder of the right to make decisions. You have got to be able to share that. And lastly again, just to harp on it one more time, is communications. Clear and concise communication throughout the team and both up and down a chain of command is very, very important.

Some organizations prefer to have someone with strong behavioral skills acting as the project manager, with technical expertise residing with the project engineer. Other organizations have found the reverse to be effective. Rose Russett, formerly the program management process manager for General Motors Powertrain, stated:

We usually appoint an individual with a technical background as the program manager and an individual with a business and/or systems background as the program administrator. This combination of skills seems to complement one another. The various line managers are ultimately responsible for the technical portions of the program, while the key responsibility of the program manager is to provide the integration of all functional deliverables to achieve the objectives of the program. With that in mind, it helps for the program manager to understand the technical issues, but they add their value not by solving specific technical problems but by leading the team through a process that will result in the best solutions for the overall program, not just for the specific functional area. The program administrator, with input from all team members, develops the program plans, identifies the critical path, and regularly communicates this information to the team throughout the life of the program. This information is used to assist with problem solving, decision making, and risk management.

10.2 CONFLICT RESOLUTION

Opponents of project management claim that the primary reason why some companies avoid changing over to a project management culture is that they fear the conflicts that inevitably accompany change. Conflicts are a way of life in companies with project management cultures. Conflict can occur on any level of the organization, and it is usually the result of conflicting objectives. The project manager is a conflict manager. In many organizations, project managers continually fight fires and handle crises arising from interpersonal and interdepartmental conflicts. They are so busy handling conflicts that they delegate the day-to-day responsibility for running their projects to the project teams. Although this arrangement is not the most effective, it is sometimes necessary, especially after organizational restructuring or after a new project demanding new resources has been initiated.

The ability to handle conflicts requires an understanding of why conflicts occur. We can ask four questions, the answers to which are usually helpful in handling, and possibly preventing, conflicts in a project management environment:

- Do the project’s objectives conflict with the objectives of other projects currently in development?

- Why do conflicts occur?

- How can we resolve conflicts?

- Is there anything we can do to anticipate and resolve conflicts before they become serious?

Although conflicts are inevitable, they can be planned for. For example, conflicts can easily develop in a team in which the members do not understand each other’s roles and responsibilities. Responsibility charts can be drawn to map out graphically who is responsible for doing what on the project. With the ambiguity of roles and responsibilities gone, the conflict is resolved or future conflict is averted.

Resolution means collaboration, and collaboration means that people are willing to rely on each other. Without collaboration, mistrust prevails and progress documentation increases.

The most common types of conflict involve the following:

- Manpower resources

- Equipment and facilities

- Capital expenditures

- Costs

- Technical opinions and trade-offs

- Priorities

- Administrative procedures

- Schedules

- Responsibilities

- Personality clashes

Each of these types of conflict can vary in intensity over the life of the project. The relative intensity can vary as a function of:

- Getting closer to project constraints

- Having met only two constraints instead of three (e.g., time and performance but not cost)

- The project life cycle itself

- The individuals who are in conflict

Conflict can be meaningful if it results in beneficial outcomes. These meaningful conflicts should be allowed to continue as long as project constraints are not violated and beneficial results accrue. An example of a meaningful conflict might be two technical specialists arguing that each has a better way of solving a problem. The beneficial result would be that each tries to find additional information to support his or her hypothesis.

Some conflicts are inevitable and occur over and over again. For example, consider a raw material and finished goods inventory. Manufacturing wants the largest possible inventory of raw materials on hand to avoid possible production shutdowns. Sales and marketing wants the largest finished goods inventory so that the books look favorable and no cash flow problems are possible.

Consider five methods that project managers can use to resolve conflicts:

- Confrontation

- Compromise

- Facilitation (or smoothing)

- Force (or forcing)

- Withdrawal

Confrontation is probably the most common method used by project managers to resolve conflict. Using confrontation, the project manager faces the conflict directly. With the help of the project manager, the parties in disagreement attempt to persuade one another that their solution to the problem is the most appropriate.

When confrontation does not work, the next approach project managers usually try is compromise. In compromise, each of the parties in conflict agrees to trade-offs or makes concessions until a solution is arrived at that everyone involved can live with. This give-and-take approach can easily lead to a win–win solution to the conflict.

The third approach to conflict resolution is facilitation. Using facilitation skills, the project manager emphasizes areas of agreement and deemphasizes areas of disagreement. For example, suppose that a project manager said, “We’ve been arguing about five points, and so far we’ve reached agreement on the first three. There’s no reason why we can’t agree on the last two points, is there?” Facilitation of a disagreement does not resolve the conflict. Facilitation downplays the emotional context in which conflicts occur.

Force is also a method of conflict resolution. A project manager uses force when he or she tries to resolve a disagreement by exerting his or her own opinion at the expense of the other people involved. Often, forcing a solution onto the parties in conflict results in a win–lose outcome. Calling in the project sponsor to resolve a conflict is another form of force project managers sometimes use.

The least used and least effective mode of conflict resolution is withdrawal. A project director can simply withdraw from the conflict and leave the situation unresolved. When this method is used, the conflict does not go away and is likely to recur later. Personality conflicts might well be the most difficult conflicts to resolve. Personality conflicts can occur at any time, with anyone, and over anything. Furthermore, they can seem almost impossible to anticipate and plan for.

Let’s look at how one company found a way to anticipate and avoid personality conflicts on one of its projects. Foster Defense Group (a pseudonym) was the government contract branch of a Fortune 500 company. The company understood the potentially detrimental effects of personality clashes on its project teams, but it did not like the idea of getting the whole team together to air dirty laundry. The company found a better solution. The project manager put the names of the project team members on a list. Then he interviewed each team member one on one and asked each to identify who on the list the team member had had a personality conflict with in the past. The information remained confidential, and the project manager was able to avoid potential conflicts by separating clashing personalities.

If at all possible, the project manager should handle conflict resolution. When the project manager is unable to defuse the conflict, then and only then should the project sponsor be brought in to help solve the problem. Even then, the sponsor should not come in and force a resolution to the conflict. Instead, the sponsor should facilitate further discussion between the project managers and the team members in conflict.

10.3 STAFFING FOR EXCELLENCE

Project manager selection is always an executive-level decision. In excellent companies, however, executives go beyond simply selecting the project manager:

- Project managers are brought on board early in the life of the project to assist in outlining the project, setting its objectives, and even planning for marketing and sales. The project manager’s role in customer relations becomes increasingly important.

- Executives assign project managers for the life of the project and project termination. Sponsorship can change over the life cycle of the project, but the project manager does not change.

- Project management is given its own career ladder.

- Project managers given a role in customer relations are also expected to help sell future project management services long before the current project is complete.

- Executives realize that project scope changes are inevitable. The project manager is viewed as a manager of change.

Companies excellent in project management are prepared for crises. Both project managers and line managers are encouraged to bring problems to the surface as quickly as possible so that there is time for contingency planning and problem solving. Replacing the project manager is no longer the first solution for problems on a project. Project managers are replaced only when they try to bury problems.

A defense contractor was behind schedule on a project, and the manufacturing team was asked to work extensive overtime to catch up. Two of the manufacturing people, both union employees, used the wrong lot of raw materials to produce a $65,000 piece of equipment needed for the project. The customer was unhappy because of the missed schedules and cost overruns that resulted from having to replace the useless equipment. An inquisition-like meeting was convened and attended by senior executives from both the customer and the contractor, the project manager, and the two manufacturing employees. When the customer’s representative asked for an explanation of what had happened, the project manager stood up and said, “I take full responsibility for what happened. Expecting people to work extensive overtime leads to mistakes. I should have been more careful.” The meeting was adjourned with no one being blamed. When word spread through the company about what the project manager did to protect the two union employees, everyone pitched in to get the project back on schedule, even working uncompensated overtime.

Human behavior is also a consideration in assigning staff to project teams. Team members should not be assigned to a project solely on the basis of technical knowledge. It has to be recognized that some people simply cannot work effectively in a team environment. For example, the director of research and development at a New England company had an employee, a 50-year-old engineer, who held two master’s degrees in engineering disciplines. He had worked for the previous 20 years on one-person projects. The director reluctantly assigned the engineer to a project team. After years of working alone, the engineer trusted no one’s results but his own. He refused to work cooperatively with the other members of the team. He even went so far as redoing all the calculations passed on to him from other engineers on the team.

To solve the problem, the director assigned the engineer to another project on which he supervised two other engineers with less experience. Again, the older engineer tried to do all of the work by himself, even if it meant overtime for him and no work for the others.

Ultimately, the director had to admit that some people are not able to work cooperatively on team projects. The director went back to assigning the engineer to one-person projects on which the engineer’s technical abilities would be useful.

Robert Hershock once observed:

There are certain people whom you just don’t want to put on teams. They are not team players, and they will be disruptive on teams. I think that we have to recognize that and make sure that those people are not part of a team or team members. If you need their expertise, you can bring them in as consultants to the team but you never, never put people like that on the team.

I think the other thing is that I would never, ever eliminate the possibility of anybody being a team member no matter what the management level is. I think if they are properly trained, these people at any level can be participators in a team concept.

In 1996, Frank Jackson believed that it was possible to find a team where any individual can contribute:

People should not be singled out as not being team players. Everyone has got the ability to be on a team and to contribute to a team based on the skills and the personal experiences that they have had. If you move into the team environment, one other thing that is very important is that you not hinder communications. Communications is the key to the success of any team and any objective that a team tries to achieve.

One of the critical arguments still being waged in the project management community is whether an employee (even a project manager) should have the right to refuse an assignment. At Minnesota Power and Light, an open project manager position was posted, but nobody applied for the job. The company recognized that the employees probably did not understand what the position’s responsibilities were. After more than 80 people were trained in the fundamentals of project management, there were numerous applications for the open position.

It’s the kiss of death to the project to assign someone to a project manager’s job if that person is not dedicated to the project management process and the accountability it demands.

10.4 VIRTUAL PROJECT TEAMS

Historically, project management was a face-to-face environment where team meetings involved all players meeting together in one room. Today, because of the size and complexity of projects, often it is impossible to find all team members located under one roof. Duarte and Snyder define seven types of virtual teams. These are shown in Table 10-1.

TABLE 10-1 TYPES OF VIRTUAL TEAMS

| Type of Team | Description |

| Network | Team membership is diffuse and fluid; members come and go as needed. Team lacks clear boundaries within the organization. |

| Parallel | Team has clear boundaries and distinct membership. Team works in the short term to develop recommendations for an improvement in a process or system. |

| Project or product development | Team has fluid membership, clear boundaries, and a defined customer base, technical requirement, and output. Longer-term team task is nonroutine, and the team has decision-making authority. |

| Work or production | Team has distinct membership and clear boundaries. Members perform regular and outgoing work, usually in one functional area. |

| Service | Team has distinct membership and supports ongoing customer network activity. |

| Management | Team has distinct membership and works on a regular basis to lead corporate activities. |

| Action | Team deals with immediate action, usually in an emergency situation. Membership may be fluid or distinct. |

Source: D. L. Duarte and N. Tennant Snyder, Mastering Virtual Teams (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2001), p. 10. Reproduced by permission of John Wiley & Sons.

Culture and technology can have a major impact on the performance of virtual teams. Duarte and Snyder have identified some of these relationships in Table 10-2.

TABLE 10-2 TECHNOLOGY AND CULTURE

| Cultural Factor | Technological Considerations |

| Power distance | Members from high-power-distance cultures may participate more freely with technologies that are asynchronous and allow anonymous input. These cultures sometimes use technology to indicate status differences between team members. |

| Uncertainty avoidance | People from cultures with high uncertainty avoidance may be slower adopters of technology. They may also prefer technology that is able to produce more permanent records of discussions and decisions. |

| Individualism–collectivism | Members from highly collectivistic cultures may prefer face-to-face interactions. |

| Masculinity–femininity | People from cultures with more “feminine” orientations are more prone to use technology in a nurturing way, especially during team startups. |

| Context | People from high-context cultures may prefer more information-rich technologies, as well as those that offer opportunities for the feeling of social presence. They may resist using technologies with low social presence to communicate with people they have never met. People from low-context cultures may prefer more asynchronous communications. |

Source: D. L Duarte and N. Tennant Snyder, Mastering Virtual Teams (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2001), p. 60.

The importance of culture cannot be understated. Duarte and Snyder identify four important points to remember concerning the impact of culture on virtual teams. The four points are:

- There are national cultures, organizational cultures, functional cultures, and team cultures. They can be sources of competitive advantages for virtual teams that know how to use cultural differences to create synergy. Team leaders and members who understand and are sensitive to cultural differences can create more robust outcomes than can members of homogeneous teams with members who think and act alike. Cultural differences can create distinctive advantages for teams if they are understood and used in positive ways.

- The most important aspect of understanding and working with cultural differences is to create a team culture in which problems can be surfaced and differences can be discussed in a productive, respectful manner.

- It is essential to distinguish between problems that result from cultural differences and problems that are performance based.

- Business practices and business ethics vary in different parts of the world. Virtual teams need to clearly articulate approaches to these that every member understands and abides by.1

10.5 REWARDING PROJECT TEAMS

Today, most companies are using project teams. However, there still exist challenges in how to reward project teams for successful performance. Parker, McAdams, and Zielinski discuss the importance of how teams are rewarded:

Some organizations are fond of saying, “We’re all part of the team,” but too often it is merely management-speak. This is especially common in conventional hierarchical organizations; they say the words but don’t follow up with significant action. Their employees may read the articles and attend the conferences and come to believe that many companies have turned collaborative. Actually, though, few organizations today are genuinely team-based.

Others who want to quibble point to how they reward or recognize teams with splashy bonuses or profit-sharing plans. But these do not by themselves represent a commitment to teams; they’re more like a gift from a rich uncle. If top management believes that only money and a few recognition programs (“team of year” and that sort of thing) reinforce teamwork, they are wrong. These alone do not cause fundamental change in the way people and teams are managed.

But in a few organizations, teaming is a key component of the corporate strategy, involvement with teams is second nature, and collaboration happens without great thought or fanfare. There are natural work groups (teams of people who do the same or similar work in the same location), permanent cross-functional teams, ad hoc project teams, process improvement teams, and real management teams. Involvement just happens.2

Why is it so difficult to reward project teams? To answer this question, we must understand what a team is and is not:

Consider this statement: an organizational unit can act like a team, but a team is not necessarily an organizational unit, at least for describing reward plans. An organizational unit is just that, a group of employees organized into an identifiable business unit that appears on the organizational chart. They may behave in a spirit of teamwork, but for the purposes of developing reward plans they are not a “team.” The organizational unit may be a whole company, a strategic business unit, a division, a department, or a work group.

A “team” is a small group of people allied by a common project and sharing performance objectives. They generally have complementary skills or knowledge and an interdependence that requires that they work together to accomplish their project’s objective. Team members hold themselves mutually accountable for their results. These teams are not found on an organization chart.3

Incentives are difficult to apply because project teams may not appear on an organizational chart. Figure 10-1 shows the reinforcement model for employees. For project teams, the emphasis is the three arrows on the right-hand side of Figure 10-1.

Figure 10-1. Reinforcement model.

Source: G. Parker, J. McAdams, and D. Zielinski, Rewarding Teams (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2000, p. 29). Reproduced by permission of John Wiley & Sons.

Project team incentives are important because team members expect appropriate rewards and recognition:

Project teams are usually, but not always, formed by management to tackle specific projects or challenges with a defined time frame—reviewing processes for efficiency or cost-savings recommendations, launching a new software product, or implementing enterprise resource planning systems are just a few examples. In other cases, teams self-form around specific issues or as part of continuous improvement initiatives such as team-based suggestion systems.

Project teams can have cross-functional membership or simply be a subset of an existing organizational unit. The person who sponsors the team—its “champion” typically creates an incentive plan with specific objective measures and an award schedule tied to achieving those measures. To qualify as an incentive, the plan must include preannounced goals, with a “do this, get that” guarantee for teams. The incentive usually varies with the value added by the project.

Project team incentive plans usually have some combination of these basic measures:

- Project milestones: Hit a milestone, on budget and on time, and all team members earn a defined amount. Although sound in theory, there are inherent problems in tying financial incentives to hitting milestones. Milestones often change for good reason (technological advances, market shifts, other developments) and you don’t want the team and management to get into a negotiation on slipping dates to trigger the incentive. Unless milestones are set in stone and reaching them is simply a function of the team doing its normal, everyday job, it’s generally best to use recognition-after-the-fact celebration of reaching milestones—rather than tying financial incentives to it.

Rewards need not always be time based, such that when the team hits a milestone by a certain date it earns a reward. If, for example, a product development team debugs a new piece of software on time, that’s not necessarily a reason to reward it. But if it discovers and solves an unsuspected problem or writes better code before a delivery date, rewards are due.

- Project completion: All team members earn a defined amount when they complete the project on budget and on time (or to the team champion’s quality standards).

- Value added: This award is a function of the value added by a project, and depends largely on the ability of the organization to create and track objective measures. Examples include reduced turnaround time on customer requests, improved cycle times for product development, cost savings due to new process efficiencies, or incremental profit or market share created by the product or service developed or implemented by the project team.

One warning about project incentive plans: they can be very effective in helping teams stay focused, accomplish goals, and feel like they are rewarded for their hard work, but they tend to be exclusionary. Not everyone can be on a project team. Some employees (team members) will have an opportunity to earn an incentive that others (non-team members) do not. There is a lack of internal equity. One way to address this is to reward core team members with incentives for reaching team goals, and to recognize peripheral players who supported the team, either by offering advice, resources, or a pair of hands, or by covering for project team members back at their regular job.

Some projects are of such strategic importance that you can live with these internal equity problems and non–team members’ grousing about exclusionary incentives. Bottom line, though, is this tool should be used cautiously.4

Some organizations focus only on cash awards. However, Parker et al. have concluded from their research that noncash awards can work equally well, if not better, than cash awards:

Many of our case organizations use non-cash awards because of their staying power. Everyone loves money, but cash payments can lose their motivational impact over time.

However, non-cash awards carry trophy value that has great staying power because each time you look at that television set or plaque you are reminded of what you or your team did to earn it. Each of the plans encourages awards that are coveted by the recipients and, therefore, will be memorable.

If you ask employees what they want, they will invariably say cash. But providing it can be difficult if the budget is small or the targeted earnings in an incentive plan are modest. If you pay out more often than annually and take taxes out, the net amount may look pretty small, even cheap. Non-cash awards tend to be more dependent on their symbolic value than their financial value.

Non-cash awards come in all forms: a simple thank-you, a letter of congratulations, time off with pay, a trophy, company merchandise, a plaque, gift certificates, special services, a dinner for two, a free lunch, a credit to a card issued by the company for purchases at local stores, specific items or merchandise, merchandise from an extensive catalogue, travel for business or a vacation with the family, and stock options. Only the creativity and imagination of the plan creators limit the choices.5

10.6 KEYS TO BEHAVIORAL EXCELLENCE

Project managers can take some distinguishing actions to ensure the successful completion of their projects. These include:

- Insisting on the right to select key project team

- Negotiating for key team members with proven track records in their fields

- Developing commitment and a sense of mission from the outset

- Seeking sufficient authority from the sponsor

- Coordinating and maintaining a good relationship with the client, parent, and team

- Seeking to enhance the public’s image of the project

- Having key team members assist in decision making and problem solving

- Developing realistic cost, schedule, and performance estimates and goals

- Maintaining backup strategies (contingency plans) in anticipation of potential problems

- Providing a team structure that is appropriate yet flexible and flat

- Going beyond formal authority to maximize its influence over people and key decisions

- Employing a workable set of project planning and control tools

- Avoiding overreliance on one type of control tool

- Stressing the importance of meeting cost, schedule, and performance goals

- Giving priority to achieving the mission or function of the end item

- Keeping changes under control

- Seeking ways to assure job security for effective project team members

Earlier in this book, I claimed that a project cannot be successful unless it is recognized as a project and gains the support of top-level management. Top-level management must be willing to commit company resources and provide the necessary administrative support so that the project becomes part of the company’s day-to-day routine of doing business. In addition, the parent organization must develop an atmosphere conducive to goo d working relationships among project manager, parent organization, and client organization.

Top-level management should take certain actions to ensure that the organization as a whole supports individual projects and project teams as well as the overall project management system. These actions include:

- Showing a willingness to coordinate efforts

- Demonstrating a willingness to maintain structural flexibility

- Showing a willingness to adapt to change

- Performing effective strategic planning

- Maintaining rapport

- Putting proper emphasis on past experience

- Providing external buffering

- Communicating promptly and accurately

- Exhibiting enthusiasm

- Recognizing that projects do, in fact, contribute to the capabilities of the whole company

Executive sponsors can take certain following actions to make project success more likely, including:

- Selecting a project manager at an early point in the project who has a proven track record in behavioral skills and technical skills

- Developing clear and workable guidelines for the project manager

- Delegating sufficient authority to the project manager so that she or he can make decisions in conjunction with the project team members

- Demonstrating enthusiasm for and commitment to the project and the project team

- Developing and maintaining short and informal lines of communication

- Avoiding excessive pressure on the project manager to win contracts

- Avoiding arbitrarily slashing or ballooning the project team’s cost estimate

- Avoiding buy-ins

- Developing close, not meddlesome, working relationships with the principal client contact and the project manager

The client organization can exert a great deal of influence on the behavioral aspects of a project by minimizing team meetings, rapidly responding to requests for information, and simply allowing the contractor to conduct business without interference. The positive actions of client organizations also include:

- Showing a willingness to coordinate efforts

- Maintaining rapport

- Establishing reasonable and specific goals and criteria for success

- Establishing procedures for making changes

- Communicating promptly and accurately

- Committing client resources as needed

- Minimizing red tape

- Providing sufficient authority to the client’s representative, especially in decision making

With these actions as the basic foundation, it should be possible to achieve behavioral success, which includes:

- Encouraging openness and honesty from the start from all participants

- Creating an atmosphere that encourages healthy competition but not cutthroat situations or liar’s contests

- Planning for adequate funding to complete the entire project

- Developing a clear understanding of the relative importance of cost, schedule, and technical performance goals

- Developing short and informal lines of communication and a flat organizational structure

- Delegating sufficient authority to the principal client contact and allowing prompt approval or rejection of important project decisions

- Rejecting buy-ins

- Making prompt decisions regarding contract okays or go-aheads

- Developing close working relationships with project participants

- Avoiding arm’s-length relationships

- Avoiding excessive reporting schemes

- Making prompt decisions on changes

Companies that are excellent in project management have gone beyond the standard actions just listed. Additional actions for excellence include the following:

- The outstanding project manager:

- Understands and demonstrates competency as a project manager

- Works creatively and innovatively in a nontraditional sense only when necessary; does not look for trouble

- Demonstrates high levels of self-motivation from the start

- Has a high level of integrity; goes above and beyond politics and gamesmanship

- Is dedicated to the company and not just the project; is never self-serving

- Demonstrates humility in leadership

- Demonstrates strong behavioral integration skills both internally and externally

- Thinks proactively rather than reactively

- Is willing to assume a great deal of risk and will spend the appropriate time needed to prepare contingency plans

- Knows when to handle complexity and when to cut through it; demonstrates tenaciousness and perseverance

- Is willing to help people realize their full potential; tries to bring out the best in people

- Communicates in a timely manner and with confidence rather than despair

- The project manager maintains high standards of performance for self and team, as shown by these approaches:

- Stresses managerial, operational, and product integrity

- Conforms to moral codes and acts ethically in dealing with people internally and externally

- Never withholds information

- Is quality conscious and cost conscious

- Discourages politics and gamesmanship; stresses justice and equity

- Strives for continuous improvement but in a cost-conscious manner

- The outstanding project manager organizes and executes the project in a sound and efficient manner by:

- Informing employees at the project kickoff meeting how they will be evaluated

- Preferring a flat project organizational structure over a bureaucratic one

- Developing a project process for handling crises and emergencies quickly and effectively

- Keeping the project team informed in a timely manner

- Not requiring excessive reporting; creating an atmosphere of trust

- Defining roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities up front

- Establishing a change management process that involves the customer

- The outstanding project manager knows how to motivate:

- Always uses two-way communication

- Is empathetic with the team and a good listener

- Involves team members in decision making; always seeks ideas and solutions; never judges an employee’s idea hastily

- Never dictates

- Gives credit where credit is due

- Provides constructive criticism rather than making personal attacks

- Publicly acknowledges credit when credit is due but delivers criticism privately

- Makes sure that team members know that they will be held accountable and responsible for their assignments

- Always maintains an open-door policy; is readily accessible, even for employees with personal problems

- Takes action quickly on employee grievances; is sensitive to employees’ feelings and opinions

- Allows employees to meet the customers

- Tries to determine each team member’s capabilities and aspirations; always looks for a good match; is concerned about what happens to the employees when the project is over

- Tries to act as a buffer between the team and administrative/operational problems

- The project manager is ultimately responsible for turning the team into a cohesive and productive group for an open and creative environment. If the project manager succeeds, the team will:

- Demonstrate innovation

- Exchange information freely

- Be willing to accept risk and invest in new ideas

- Have the necessary tools and processes to execute the project

- Dare to be different; is not satisfied with simply meeting the competition

- Understand the business and the economics of the project

- Try to make sound business decisions rather than just sound project decisions

10.7 PROACTIVE VERSUS REACTIVE MANAGEMENT

Perhaps one of the biggest behavioral challenges facing a project manager, especially a new project manager, is learning how to be proactive rather than reactive. Kerry R. Wills discusses this problem.6

* * *

Proactive Management Capacity Propensity

In today’s world, project managers often get tapped to manage several engagements at once. This usually results in them having just enough time to react to the problems of the day that each project is facing. What they are not doing is spending the time to look ahead on each project to plan for upcoming work, thus resulting in more fires that need to be put out. There used to be an arcade game called “whack-a-mole” where the participant had a mallet and would hit each mole with it when one would pop up. Each time a mole was hit, a new mole would pop up. The cycle of spending time putting out fires and ignoring problems that cause more fires can be thought of as “project whack-a-mole.”

It is my experience that proactive management is one of the most effective tools that project managers can use to ensure the success of their projects. However, it is a difficult situation to manage several projects while still having enough time to look ahead. I call this ability to spend time looking ahead the “Proactive Management Capacity Propensity” (PMCP). This article demonstrates the benefits of proactive management, define the PMCP, and propose ways of increasing the PMCP and thus the probability of success on the projects.

Proactive Management

Project management involves a lot of planning up front including work plans, budgets, resource allocations, and so on. The best statistics that I have seen on the accuracy of initial plans says there is a 30 percent positive or negative variance from the original plans at the end of a project. Therefore, once the plans have been made and the project has started, the project manager needs to constantly reassess the project to understand the impact of the 60 percent unknowns that will occur.

The dictionary defines proactive as “acting in advance to deal with an expected difficulty.” By “acting in advance,” a project manager has some influence over the control of the unknowns. However, without acting in advance, the impacts of the unknowns will be greater as the project manager will be reacting to the problem once it has snowballed.

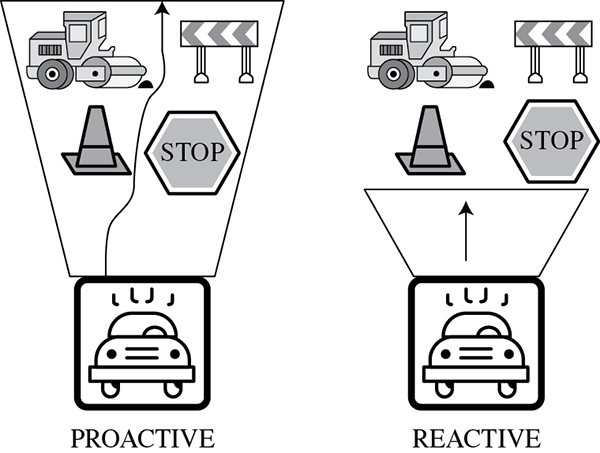

When I drive into work in the morning, I have a plan and schedule. I leave my house, take certain roads, and get to work in 40 minutes. If I were to treat driving to work as a project (having a specific goal with a finite beginning and end), then I have two options to manage my commute: (See Figure 10-2.)

Figure 10-2. Driving metaphor.

By proactively managing my commute, I watch the news in the morning to see the weather and traffic. Although I had a plan, if there is construction on one of the roads that I normally take, then I can always change that plan and take a different route to ensure that my schedule gets met. If I know that there may be snow, then I can leave earlier and give myself more time to get to work. As I am driving, I look ahead in the road to see what is coming up. There may be an accident or potholes that I will want to avoid and this gives me time to switch lanes.

A reactive approach to my commute could be assuming that my original plan will work fully. As I get on the highway, if there is construction, then I have to sit in it because by the time I realize the impact, I have passed all of the exit ramps. This results in me missing my schedule goal. The same would happen if I walked outside and saw a foot of snow. I now have a chance to scope since I have the added activity of shoveling out my driveway and car. Also, if I am a reactive driver, then I don’t see the pothole until I have driven over it (which may lead to a budget variance since I now need new axles).

Benefits

This metaphor demonstrates that reactive management is detrimental to projects because by the time that you realize that there is a problem, it usually has a schedule, scope, or cost impact. There are several other benefits to proactive management:

- Proactively managing a plan allows the project manager to see what activities are coming up and start preparing for them. This could be something as minor as setting up conference rooms for meetings. I have seen situations were tasks were not completed on time because of something as minor as logistics.

- Understanding upcoming activities also allows for the proper resources to be in place. Oftentimes, projects require people from outside of the project team and lining them up is always a challenge. By preparing people in advance, there is a higher probability that they can be ready when needed.

The Relationship

The project manager should constantly be replanning. By looking at all upcoming activities as well as the current ones, it can give a gauge of the probability of success, which can be managed rather than waiting until the day before something is due to realize that the schedule cannot be met.

Proactive management also allows time to focus on quality. Reactive management usually is characterized by rushing to fix whatever “mole” has popped up as quickly as possible. This usually means a patch rather than the appropriate fix. By planning for the work appropriately, it can be addressed properly, which reduces the probability of rework.

As previously unidentified work arises, it can be planned for rather than assuming that “we can just take it on.”

Proactive management is extremely influential over the probability of success of a project because it allows for replanning and the ability to address problems well before they have a significant impact.

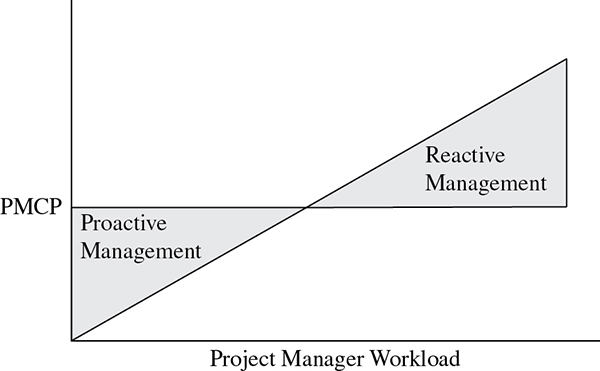

I have observed a relationship between the amount of work that a project manager has and their ability to manage proactively. As project managers get more work and more concurrent projects, their ability to manage proactively goes down.

The relationship between project manager workload and the ability to manage proactively is shown in Figure 10-3. As project managers have increased work, they have less capacity to be proactive to and wind up becoming more reactive.

Figure 10-3. Proactivity graph.

Not all projects and project managers are equal. Some project managers can handle several projects well, and some projects require more focus than others. I have therefore labeled this factor the Project Management Capacity Propensity. That is, the sum of those qualities that allow a project manager to proactively manage projects.

There are several factors that make up the PMCP that I outline below.

Project manager skill sets have an impact on the PMCP. Having good time management and organization techniques can influence how much a PM can focus on looking ahead. A project manager who is efficient with their time has the ability to review more upcoming activities and plan for them.

Project manager expertise in the project is also influential to the PMCP. If the PM is an expert in the business or the project, this may allow for quicker decisions since they will not need to seek out information or clarification (all of which takes away time).

The PMCP is also impacted by team composition. If the project manager is on a large project and has several team leads who manage plans, then they have an increased ability to focus on replanning and upcoming work. Also, having team members who are experts in their field will require less focus from the project manager.

Increasing the PMCP

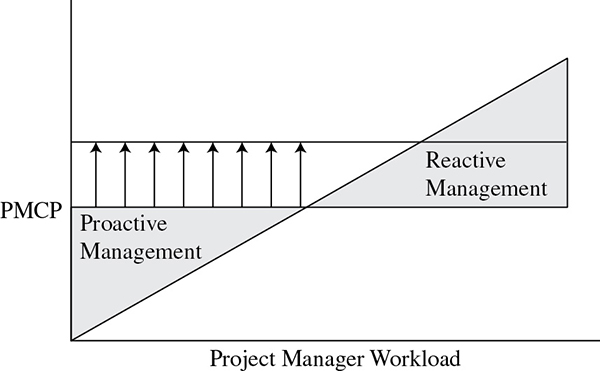

The good news about the PMCP is that it can be increased.

Project managers can look for ways to increase their skill sets through training. There are several books and seminars on time management, prioritization, and organization. Attending these can build the effectiveness of the time spent by the PM on their activities.

The PM can also reevaluate the team composition. By getting stronger team leads or different team members, the PM can offload some of their work and spend more time focusing on proactive management.

All of these items can increase the PMCP and result in an increased ability to manage proactively. Figure 10-4 shows how a PMCP increase raises the bar and allows for more proactive management with the same workload.

Figure 10-4. Increasing PMCP.

Conclusion

To proactively manage a project is to increase your probability of being successful. There is a direct correlation between the workload that a PM has and their ability to look ahead. Project managers do have control over certain aspects that can give them a greater ability to focus on proactive management. These items, the PMCP, can be increased through training and having the proper team.

Remember to keep your eyes on the road.