4

Project Management Methodologies

4.0 INTRODUCTION

In Chapter 1 we described the life-cycle phases for achieving maturity in project management. The fourth phase was the growth phase, which included the following:

- Establish life-cycle phases.

- Develop a project management methodology.

- Base the methodology upon effective planning.

- Minimize scope changes and scope creep.

- Select the appropriate software to support the methodology.

The importance of a good methodology cannot be overstated. Not only will it improve performance during project execution, but it will also allow for better customer relations and customer confidence. Good methodologies can also lead to sole-source or single-source procurement contracts.

Creating a workable methodology for project management is no easy task. One of the biggest mistakes made is developing a different methodology for each type of project. Another is failing to integrate the project management methodology and project management tools into a single process, if possible. When companies develop project management methodologies and tools in tandem, two benefits emerge: First, the work is accomplished with fewer scope changes. Second, the processes are designed to create minimal disturbance to ongoing business operations.

This chapter discusses the components of a project management methodology and some of the most widely used project management tools. Detailed examples of methodologies at work are also included.

4.1 EXCELLENCE DEFINED

Excellence in project management is often regarded as a continuous stream of successfully managed projects. Without a project management methodology, repetitive successfully completed projects may be difficult to achieve.

Today, everyone seems to agree somewhat on the necessity for a project management methodology. However, there is still disagreement on the definition of excellence in project management, the same way that companies have different definitions for project success. In this section, we discuss some of the different definitions of excellence in project management.

Some definitions of excellence can be quite simple and achieve the same purpose as complex definitions. According to a spokesperson from Motorola:

Excellence in project management can be defined as:

- Strict adherence to scheduling practices

- Regular senior management oversight

- Formal requirements change control

- Formal issue and risk tracking

- Formal resource tracking

- Formal cost tracking

A spokesperson from AT&T defined excellence in this way:

Excellence [in project management] is defined as a consistent Project Management Methodology applied to all projects across the organization, continued recognition by our customers, and high customer satisfaction. Also, our project management excellence is a key selling factor for our sales teams. This results in repeat business from our customers. In addition, there is internal acknowledgement that project management is value-added and a must have.

Doug Bolzman, Consultant Architect, PMP, ITIL expert at Hewlett-Packard, discusses his view of excellence in project management:

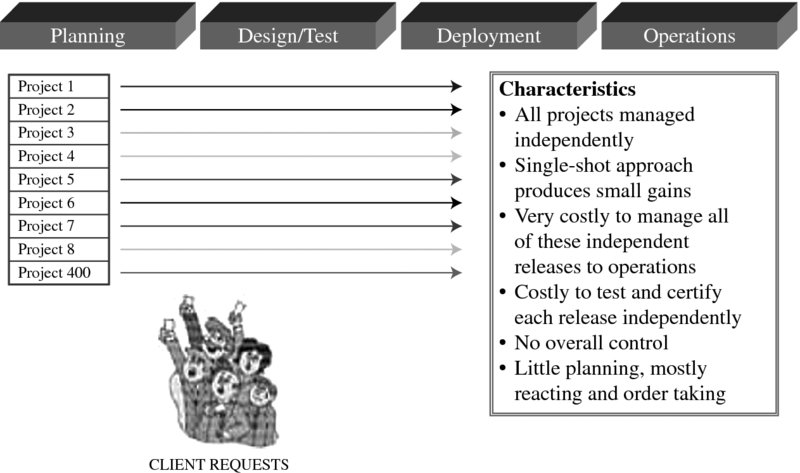

Excellence is rated, not by managing the pieces, but by understanding how the pieces fit together, support each other’s dependencies, and provide value to the business. If project management only does what it is asked to do, such as manage 300 individual projects in the next quarter, it is providing a low value-added function that basically is the “pack mule” that is needed, but only does what it is asked—and no more. Figures 4-1 and 4-2 demonstrate that if mapping project management to a company’s overall release management framework, each project is managed independently with the characteristics shown.

Using the same release framework and the same client requests, project management disciplines can understand the nature of the requirements and provide a valuable service to bundle the same types of requests (projects) to generate a forecast of the work, which will assist the company in balancing its financials, expectations, and resources. This function can be done within the PMO.

Figure 4-1. Release management stages.

Figure 4-2. Release management stages: bundling requests.

4.2 RECOGNIZING THE NEED FOR METHODOLOGY DEVELOPMENT

Simply having a project management methodology and following it do not lead to success and excellence in project management. The need for improvements in the system may be critical. External factors can have a strong influence on the success or failure of a company’s project management methodology. Change is a given in the current business climate, and there is no sign that the future will be any different. The rapid changes in technology that have driven changes in project management over the past two decades are not likely to subside. Another trend, the increasing sophistication of consumers and clients, is likely to continue, not go away. Cost and quality control have become virtually the same issue in many industries. Other external factors include rapid mergers and acquisitions and real-time communications.

Project management methodologies are organic processes and need to change as the organization changes in response to the ever-evolving business climate. Such changes, however, require that managers on all levels be committed to them and have a vision that calls for the development of project management systems along with the rest of the organization’s other business systems.

Today, companies are managing their business by projects. This is true for both non–project-driven and project-driven organizations. Virtually all activities in an organization can be treated as some sort of project. Therefore, it is only fitting that well-managed companies regard a project management methodology as a way to manage the entire business rather than just projects. Business processes and project management processes will be merged together as the project manager is viewed as the manager of part of a business rather than just the manager of a project.

Developing a standard project management methodology is not for every company. For companies with small or short-term projects, such formal systems may not be cost-effective or appropriate. However, for companies with large or ongoing projects, developing a workable project management system is mandatory.

For example, a company that manufactures home fixtures had several project development protocols in place. When it decided to begin using project management systematically, the complexity of the company’s current methods became apparent. The company had multiple system development methodologies based on the type of project. This became awkward for employees who had to struggle with a different methodology for each project. The company then opted to create a general, all-purpose methodology for all projects. The new methodology had flexibility built into it. According to one spokesman for the company:

Our project management approach, by design, is not linked to a specific systems development methodology. Because we believe that it is better to use a (standard) systems development methodology than to decide which one to use, we have begun development of a guideline systems development methodology specific for our organization. We have now developed prerequisites for project success. These include:

- A well-patterned methodology

- A clear set of objectives

- Well-understood expectations

- Thorough problem definition

During the late 1980s, merger mania hit the banking community. With the lowering of costs due to economies of scale and the resulting increased competitiveness, the banking community recognized the importance of using project management for mergers and acquisitions. The quicker the combined cultures became one, the less the impact on the corporation’s bottom line.

The need for a good methodology became apparent, according to a spokesperson at one bank:

The intent of this methodology is to make the process of managing projects more effective: from proposal to prioritization to approval through implementation. This methodology is not tailored to specific types or classifications of projects, such as system development efforts or hardware installations. Instead, it is a commonsense approach to assist in prioritizing and implementing successful efforts of any jurisdiction.

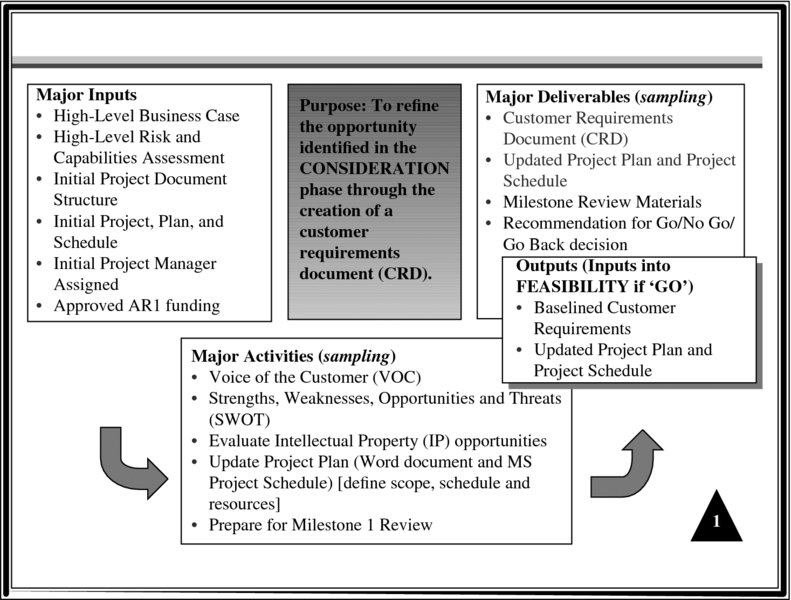

In 1996, the information services (IS) division of one bank formed an IS reengineering team to focus on developing and deploying processes and tools associated with project management and system development. The mission of the IS reengineering team was to improve performance of IS projects, resulting in increased productivity and improved cycle time, quality, and satisfaction of project customers.

According to a spokesperson at the bank, the process began as follows:

Information from both current and previous methodologies used by the bank was reviewed, and the best practices of all these previous efforts were incorporated into this document. Regardless of the source, project methodology phases are somewhat standard fare. All projects follow the same steps, with the complexity, size, and type of project dictating to what extent the methodology must be followed. What this methodology emphasizes are project controls and the tie of deliverables and controls to accomplishing the goals.

To determine the weaknesses associated with past project management methodologies, the IS reengineering team conducted various focus groups. These focus groups concluded that the following had been lacking from previous methodologies:

- Management commitment

- A feedback mechanism for project managers to determine the updates and revisions needed to the methodology

- Adaptable methodologies for the organization

- A training curriculum for project managers on the methodology

- Focus on consistent and periodic communication on the methodology deployment progress

- Focus on the project management tools and techniques

Based on this feedback, the IS reengineering team successfully developed and deployed a project management and system development methodology. Beginning June 1996 through December 1996, the target audience of 300 project managers became aware and applied a project management methodology and standard tool (MS Project).

The bank did an outstanding job of creating a methodology that reflects guidelines rather than policies and provides procedures that can easily be adapted on any project in the bank. Up to 2017, the bank had continuously added flexibility into its project management approach, making it easier to manage all types of projects. Some of the selected components of the project management methodology are discussed next.

Organizing

With any project, you need to define what needs to be accomplished and decide how the project is going to achieve those objectives. Each project begins with an idea, vision, or business opportunity, a starting point that must be tied to the organization’s business objectives. The project charter is the foundation of the project and forms the contract with the parties involved. It includes a statement of business needs, an agreement of what the project is committed to deliver, an identification of project dependencies, the roles and responsibilities of the team members involved, and the standards for how project budget and project management should be approached. The project charter defines the boundaries of the project, and the project team has a great deal of flexibility as long as the members remain within the boundaries.

Planning

Once the project boundaries are defined, sufficient information must be gathered to support the goals and objectives and to limit risk and minimize issues. This component of project management should generate sufficient information to clearly establish the deliverables that need to be completed, define the specific tasks that will ensure completion of these deliverables, and outline the proper level of resources. Each deliverable affects whether each phase of the project will meet its goals, budget, quality, and schedule. For simplicity’s sake, some projects take a four-phase approach:

- Proposal. Project initiation and definition

- Planning. Project planning and requirements definition

- Development. Requirement development, testing, and training

- Implementation. Rollout of developed requirements for daily operation

Each phase contains review points to help ensure that project expectations and quality deliverables are achieved. It is important to identify the reviewers for the project as early as possible to ensure the proper balance of involvement from subject matter experts and management.

Managing

Throughout the project, management and control of the process must be maintained. This is the opportunity for the project manager and team to evaluate the project, assess project performance, and control the development of the deliverables. During the project, the following areas should be managed and controlled:

- Evaluate daily progress of project tasks and deliverables by measuring budget, quality, and cycle time.

- Adjust day-to-day project assignments and deliverables in reaction to immediate variances, issues, and problems.

- Proactively resolve project issues and changes to control unnecessary scope creep.

- Aim for client satisfaction.

- Set up periodic and structured reviews of the deliverables.

- Establish a centralized project control file.

Two essential mechanisms for successfully managing projects are solid status-reporting procedures and issues and change management procedures. Status reporting is necessary for keeping the project on course and in good health. The status report should include the following:

- Major accomplishment to date

- Planned accomplishments for the next period

- Project progress summary:

- Percentage of effort hours consumed

- Percentage of budget costs consumed

- Percentage of project schedule consumed

- Project cost summary (budget versus actual)

- Project issues and concerns

- Impact to project quality

- Management action items

Issues-and-change management protects project momentum while providing flexibility. Project issues are matters that require decisions to be made by the project manager, project team, or management. Management of project issues needs to be defined and properly communicated to the project team to ensure the appropriate level of issue tracking and monitoring. This same principle relates to change management because inevitably the scope of a project will be subject to some type of change. Any change management on the project that impacts the cost, schedule, deliverables, and dependent projects is reported to management. Reporting of issue and change management should be summarized in the status report, noting the number of open and closed items of each. This assists management in evaluating the project health.

Simply having a project management methodology and using it does not lead to maturity and excellence in project management. There must exist a “need” for improving the system so it moves toward maturity. Project management systems can change as the organization changes. However, management must be committed to the change and have the vision to let project management systems evolve with the organization.

4.3 ENTERPRISE PROJECT MANAGEMENT METHODOLOGIES

Most companies today seem to recognize the need for one or more project management methodologies but either create the wrong methodologies or misuse these that have been created. Many times, companies rush into the development or purchasing of a methodology without any understanding of the need for one other than the fact that their competitors have a methodology. According to Jason Charvat:

Using project management methodologies is a business strategy allowing companies to maximize the project’s value to the organization. The methodologies must evolve and be “tweaked” to accommodate a company’s changing focus or direction. It is almost a mind-set, a way that reshapes entire organizational processes: sales and marketing, product design, planning, deployment, recruitment, finance, and operations support. It presents a radical cultural shift for many organizations. As industries and companies change, so must their methodologies. If not, they’re losing the point.1

Methodologies are a set of forms, guidelines, templates, and checklists that can be applied to a specific project or situation. It may not be possible to create a single enterprise-wide methodology that can be applied to each and every project. Some companies have been successful doing this, but there are still many companies that successfully maintain more than one methodology. Unless the project manager is capable of tailoring the EPM methodology to his or her needs, more than one methodology may be necessary.

There are several reasons why good intentions often go astray. At the executive levels, methodologies can fail if the executives have a poor understanding of what a methodology is and believe that a methodology is:

- A quick fix

- A silver bullet

- A temporary solution

- A cookbook approach for project success2

At the working levels, methodologies can also fail if they:

- Are abstract and high level

- Contain insufficient narratives to support these methodologies

- Are not functional or do not address crucial areas

- Ignore the industry standards and best practices

- Look impressive but lack real integration into the business

- Use nonstandard project conventions and terminology

- Compete for similar resources without addressing this problem

- Don’t have any performance metrics

- Take too long to complete because of bureaucracy and administration3

Deciding on the type of methodology is not an easy task. There are many factors to consider, such as:

- The overall company strategy—how competitive are we as a company?

- The size of the project team and/or scope to be managed

- The priority of the project

- How critical the project is to the company

- How flexible the methodology and its components are4

Project management methodologies are created around the project management maturity level of the company and the corporate culture. If the company is reasonably mature in project management and has a culture that fosters cooperation, effective communications, teamwork, and trust, then a highly flexible methodology can be created based on guidelines, forms, checklists, and templates. Project managers can pick and choose the parts of the methodology that are appropriate for a particular client. Organizations that do not possess either of these two characteristics rely heavily on methodologies constructed with rigid policies and procedures, thus creating significant paperwork requirements with accompanying cost increases and removing the flexibility that the project manager needs for adapting the methodology to the needs of a specific client.

Charvat describes these two types as light methodologies and heavy methodologies.5

Light Methodologies

Ever-increasing technological complexities, project delays, and changing client requirements brought about a small revolution in the world of development methodologies. A totally new breed of methodology—which is agile and adaptive and involves the client every part of the way—is starting to emerge. Many of the heavyweight methodologists were resistant to the introduction of these “lightweight” or “agile” methodologies.6 These methodologies use an informal communication style. Unlike heavyweight methodologies, lightweight projects have only a few rules, practices, and documents. Projects are designed and built on face-to-face discussions, meetings, and the flow of information to clients. The immediate difference of using light methodologies is that they are much less documentation oriented, usually emphasizing a smaller amount of documentation for the project.

Heavy Methodologies

The traditional project management methodologies (i.e., the systems development life-cycle approach) are considered bureaucratic or “predictive” in nature and have resulted in many unsuccessful projects. These heavy methodologies are becoming less popular. These methodologies are so laborious that the whole pace of design, development, and deployment slows down—and nothing gets done. Project managers tend to predict every milestone because they want to foresee every technical detail (i.e., software code or engineering detail). This leads managers to start demanding many types of specifications, plans, reports, checkpoints, and schedules. Heavy methodologies attempt to plan a large part of a project in great detail over a long span of time. This works well until things start changing, and the project managers inherently try to resist change.

EPM methodologies can enhance the project planning process and provide some degree of standardization and consistency. Companies have come to realize that enterprise project management methodologies work best if the methodology is based on templates rather than rigid policies and procedures. The International Institute for Learning has created a Unified Project Management Methodology (UPMMTM)7 with templates categorized according to the Areas of Knowledge in the sixth edition of the PMBOK® Guide:

- Communication

- Project Charter

- Project Procedures Document

- Project Change Requests Log

- Project Status Report

- PM Quality Assurance Report

- Procurement Management Summary

- Project Issues Log

- Project Management Plan

- Project Performance Report

- Cost

- Project Schedule

- Risk Response Plan and Register

- Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)

- Work Package

- Cost Estimates Document

- Project Budget

- Project Budget Checklist

- Human Resources

- Project Charter

- Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)

- Communications Management Plan

- Project Organization Chart

- Project Team Directory

- Responsibility Assignment Matrix (RAM)

- Project Management Plan

- Project Procedures Document

- Kick-Off Meeting Checklist

- Project Team Performance Assessment

- Project Manager Performance Assessment

- Integration

- Project Procedures Overview

- Project Proposal

- Communications Management Plan

- Procurement Plan

- Project Budget

- Project Procedures Document

- Project Schedule

- Responsibility Assignment Matrix (RAM)

- Risk Response Plan and Register

- Scope Statement

- Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)

- Project Management Plan

- Project Change Requests Log

- Project Issues Log

- Project Management Plan Changes Log

- Project Performance Report

- Lessons Learned Document

- Project Performance Feedback

- Product Acceptance Document

- Project Charter

- Closing Process Assessment Checklist

- Project Archives Report

- Procurement

- Project Charter

- Scope Statement

- Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)

- Procurement Plan

- Procurement Planning Checklist

- Procurement Statement of Work (SOW)

- Request for Proposal Document Outline

- Project Change Requests Log

- Contract Formation Checklist

- Procurement Management Summary

- Quality

- Project Charter

- Project Procedures Overview

- Work Quality Plan

- Project Management Plan

- Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)

- PM Quality Assurance Report

- Lessons Learned Document

- Project Performance Feedback

- Project Team Performance Assessment

- PM Process Improvement Document

- Risk

- Procurement Plan

- Project Charter

- Project Procedures Document

- Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)

- Risk Response Plan and Register

- Scope

- Project Scope Statement

- Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)

- Work Package

- Project Charter

- Time

- Activity Duration Estimating Worksheet

- Cost Estimates Document

- Risk Response Plan and Register Medium

- Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)

- Work Package

- Project Schedule

- Project Schedule Review Checklist

- Stakeholder Management

- Project Charter

- Change Control Plan

- Schedule Change Request Form

- Project Issues Log

- Responsibility Assignment matrix (RAM)

4.4 BENEFITS OF A STANDARD METHODOLOGY

For companies that understand the importance of a standard methodology, the benefits are numerous. These benefits can be classified as both short- and long-term benefits. Short-term benefits were described by one company as:

- Decreased cycle time and lower costs

- Realistic plans with greater possibilities of meeting time frames

- Better communications as to “what” is expected from groups and “when”

- Feedback: lessons learned

These short-term benefits focus on key performance indicators (KPIs) or, simply stated, the execution of project management. Long-term benefits seem to focus more upon critical success factors and customer satisfaction. Long-term benefits of development and execution of a world-class methodology include:

- Faster time to market through better scope control

- Lower overall program risk

- Better risk management, which leads to better decision making

- Greater customer satisfaction and trust, which lead to increased business and expanded responsibilities for the tier 1 suppliers

- Emphasis on customer satisfaction and value-added rather than internal competition between functional groups

- Customer treating the contractor as a partner rather than as a commodity

- Contractor assisting the customer during strategic planning activities

Perhaps the largest benefit of a world-class methodology is the acceptance and recognition by customers. If one of your critically important customers develops its own methodology, that customer could “force” you to accept it and use it in order to remain a supplier. But if you can show that your methodology is superior or equal to the customer’s, your methodology will be accepted, and an atmosphere of trust will prevail.

One contractor recently found that a customer had so much faith in and respect for its methodology that the contractor was invited to participate in the customer’s strategic planning activities. The contractor found itself treated as a partner rather than as a commodity or just another supplier. This resulted in sole-source procurement contracts for the contractor.

Developing a standard methodology that encompasses the majority of a company’s projects and is accepted by the entire organization is a difficult undertaking. The hardest part might very well be making sure that the methodology supports both the corporate culture and the goals and objectives set forth by management. Methodologies that require changes to a corporate culture may not be well accepted by the organization. Nonsupportive cultures can destroy even seemingly good project management methodologies.

During the 1980s and 1990s, several consulting companies developed their own project management methodologies, most frequently for information systems projects, and then pressured clients into purchasing the methodology rather than helping them develop a methodology more suited to their own needs. Although there may have been some successes, there appeared to be significantly more failures than successes. A hospital purchased a $130,000 project management methodology with the belief that this would be the solution to its information system needs. Unfortunately, senior management made the purchasing decision without consulting the workers who would be using the system. In the end, the package was never used.

Another company purchased a similar package, discovering too late that the package was inflexible and the organization, specifically the corporate culture, would need to change to use the methodology effectively. The vendor later admitted that the best results would occur if no changes were made to the methodology.

These types of methodologies are extremely rigid and based on policies and procedures. The ability to custom design the methodology to specific projects and cultures was nonexistent, and eventually these methodologies fell by the wayside—but after the vendors made significant profits. Good methodologies must be flexible.

4.5 CRITICAL COMPONENTS

It is almost impossible to become a world-class company with regard to project management without having a world-class methodology. Years ago, perhaps only a few companies really had world-class methodologies. Today, because of the need for survival and stiffening competition, numerous companies have good methodologies.

The characteristics of a world-class methodology include:

- Maximum of six life-cycle phases

- Life-cycle phases overlap

- End-of-phase gate reviews

- Integration with other processes

- Continuous improvement (i.e., hear the voice of the customer)

- Customer oriented (interface with customer’s methodology)

- Companywide acceptance

- Use of templates (level 3 WBS)

- Critical path scheduling (level 3 WBS)

- Simplistic, standard bar chart reporting (standard software)

- Minimization of paperwork

Generally speaking, each life-cycle phase of a project management methodology requires paperwork, control points, and perhaps special administrative requirements. Having too few life-cycle phases is an invitation for disaster, and having too many life-cycle phases may drive up administrative and control costs. Most companies prefer a maximum of six life-cycle phases.

Historically, life-cycle phases were sequential in nature. However, because of the necessity for schedule compression, life-cycle phases today will overlap. The amount of overlap will be dependent on the magnitude of the risks the project manager will take. The more the overlap, the greater the risk. Mistakes made during overlapping activities are usually more costly to correct than mistakes during sequential activities. Overlapping life-cycle phases requires excellent up-front planning.

End-of-phase gate reviews are critical for control purposes and verification of interim milestones. With overlapping life-cycle phases, there are still gate reviews at the end of each phase, but they are supported by intermediate reviews during the life-cycle phases.

World-class project management methodologies are integrated with other management processes, such as change management, risk management, total quality management, and concurrent engineering. This produces a synergistic effect, which minimizes paperwork, minimizes the total number of resources committed to the project, and allows the organization to perform capacity planning to determine the maximum workload that the organization can support.

World-class methodologies are continuously enhanced through KPI reviews, lessons-learned updates, benchmarking, and customer recommendations. The methodology itself could become the channel of communication between customer and contractor. Effective methodologies foster customer trust and minimize customer interference in the project.

Project management methodologies must be easy for workers to use as well as covering most of the situations that can arise on a project. Perhaps the best way is to have the methodology placed in a manual that is user friendly.

Excellent methodologies try to make it easier to plan and schedule projects. This is accomplished by using templates for the top three levels of the WBS. Simply stated, using WBS level 3 templates, standardized reporting with standardized terminology exists. The differences between projects will appear at the lower levels (i.e., levels 4 to 6) of the WBS. This also leads to a minimization of paperwork.

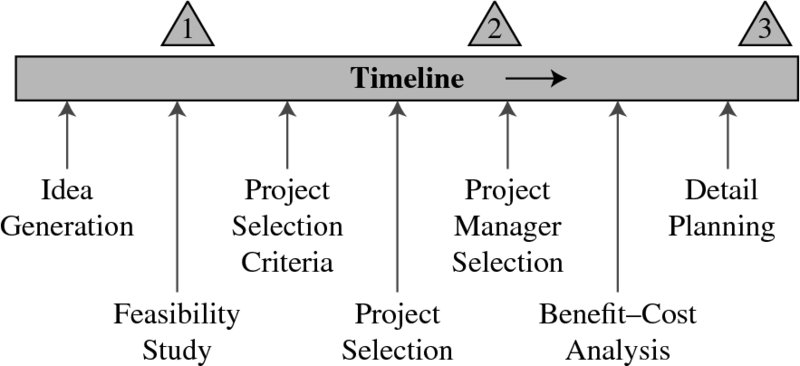

Today, companies seem to be promoting the use of the project charter concept as a component of a methodology, but not all companies create the project charter at the same point in the project life cycle, as shown in Figure 4-3. The three triangles in the figure show possible locations where the charter can be prepared:

- In the first triangle, the charter is prepared immediately after the feasibility study is completed. At this point, the charter contains the results of the feasibility study as well as documentation of any assumptions and constraints that were considered. The charter is then revisited and updated once this project is selected.

- In the second triangle, which seems to be the preferred method, the charter is prepared after the project is selected and the project manager has been assigned. The charter includes the authority granted to the project manager, but for this project only.

- In the third method, the charter is prepared after detail planning is completed. The charter contains the detailed plan. Management will not sign the charter until after detail planning is approved by senior management. Then, and only then, does the company officially sanction the project. Once management signs the charter, the charter becomes a legal agreement between the project manager and all involved line managers as to what deliverables will be met and when.

Figure 4-3. When to prepare the charter.

4.6 AIRBUS SPACE AND DEFENCE: INTEGRATION OF THE APQP METHODOLOGY WITHIN PROJECT LIFE CYCLE8

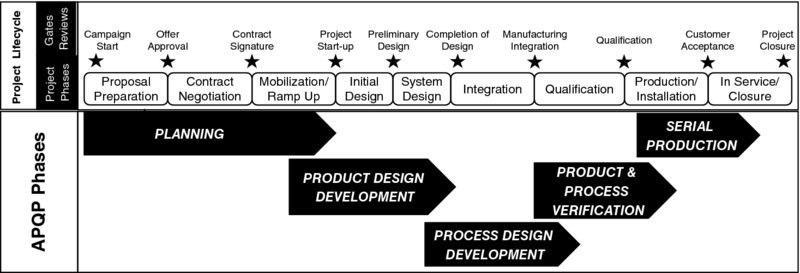

The Advanced Product Quality Planning (APQP) is a project management tool that provides effective early warning by monitoring on-quality and on-time delivery of key deliverables from the planning phase until the delivery/serial production with the objective to avoid costly issues and reworks due to immature deliverables and to increase our internal and external customers’ satisfaction. These key deliverables are called “critical to quality” (CTQ).

This section provides an integration of this methodology within project life cycle through the definition of standard milestones, or gate reviews, where the project is assessed to ensure the maturity to go to the next phase. The project life cycle defines every stage of a project, providing visibility on the predecessor steps, on what will be the upcoming steps, on what other functions shall be involved, on what interfaces are to be delivered, on what results are already achieved and by whom, and on what results are to be created or developed by the next phase. Gate reviews are held at key milestones within all campaigns, programs, and projects. Gates reviews provide an objective assessment of progress against key success criteria agreed for the phase and acceptability of the forward plan and the readiness to proceed to the next phase with the objective to prevent further problems due to immature status. A customer review is not a substitute for a ate review. The main principles of gate reviews are:

- Ensuring the maturity of the project vis-à-vis the specified objectives and the availability of resources. Confirming the availability of resources, tools, and facilities as well as potential obsolescence and process issues. Facilitating the identification and utilization of applicable lessons learned.

- Gate reviews are arranged only when other related reviews have already passed (e.g., sales, commercial and engineering/technical, and other reviews); in order to avoid duplication of effort, gate reviews take into account the findings and actions of other related reviews. To further facilitate the cross-functional integration of project key stakeholders (e.g., operations; corporate functions like security, commercial, finance and legal, quality, engineering, support and service, etc.).

- Provide top management with a structured and independent assessment of program/project status; assess the program/project based on “Four Eyes Principle,” where the person who assesses the program/project is not the same one who is currently leading or performing the program/project itself. Provide transparency and unbiased opinion with respect to complex programs/projects, and provide value-add from expert reviews of the project.

The integration of APQP within project life cycle is performing through the matching of APQP phases with gate reviews, as described in Figure 4-4. Respectively, each assessment criteria of each gate review contains the expected output and associated critical-to-quality deliverable to be assessed.

Figure 4-4. APQP Phase with Gate Reviews

Table 4-1 shows an example of a criteria assessment for the gate review.

TABLE 4-1 CRITERIA ASSESSMENT

| Criteria | Project Assessment | APQP Assessment | Project Evidence or Deliverable to assess |

| Partner / Supplier Contract |

Are Supplier/Subcontractor related contracts formally finalized, signed, and kept up-to-date including validated SOW and relevant flow-down from customer contract? Are all changes in requirements (specification, terms, conditions) covered by binding agreements with suppliers/subcontractors? |

Requirement Transfer to Suppliers: Supplier statement of compliance to requirements is considered via the supplier requirement confirmation. Subtier Supplier Selection: The list is required in our requirements but:

Set up depending on criticality of supplier and product |

Supplier/Subcontractor List/ Partner/Supplier/Subcontractor Contract Critical to Quality Element: Technical specification, interface specification/list of subtier suppliers, subtier quality control/surveillance plan |

4.7 PROJECT QUALITY GATES—STRUCTURED APPROACH TO ENSURE PROJECT SUCCESS9

Project quality is paramount in delivery of SAP projects; this fact is reflected in structured approach to quality management for SAP solution delivery—Quality Built In. The staple of the quality approach in SAP projects is the execution of formal project quality gates. The quality gates are defined in the ASAP (Accelerated SAP project delivery methodology) project delivery methodology that SAP and its customers and partners use for project planning, management, and delivery. Each project type has predetermined number of quality gates (Q-Gates) executed at key milestones of the project, as shown in Figure 4-5.

Figure 4-5. Project quality gates are defined in the project management plan and are set at critical stages in the project life cycle.

SAP believes that the quality gates are essential for success of any project regardless of deployment strategy—like traditional or agile. The quality gates are integrated not only into our delivery methodology, but they are also coded into our delivery policies and internal systems. The results of each quality gate are recorded in the corporate project management information system and are regularly reviewed and reported on. A dedicated quality team in SAP has accountability for management of the quality gates, review of project health and follow-up with project manager, stakeholders and leadership.

The project quality gates in the ASAP methodology provide clear guidance to project managers, stakeholders, and project teams on how to structure and perform the quality gate review. During each quality gate, the quality assurance manager assesses completeness and quality of each deliverable produced in the project according to predefined quality gate checklist, which includes not only deliverable name but also detailed acceptance criteria. Each deliverable in the checklist is marked as either mandatory or optional for completion of the quality gate. Upon completion of the quality gate, the QA manager assesses pass/fail score for the quality gateand proposes follow-up plans to take corrective actions to address deficiencies identified in this process.

The formal quality built-in process has been shown to have positive impacts on customer satisfaction and improved overall project portfolio health, and it has positively impacted revenue.

ASAP Methodology

The ASAP methodology is a structured, repeatable, prescriptive way to deliver SAP projects and innovate project delivery. SAP delivery projects follow structured, repeatable, and prescriptive methodology for implementation. The ASAP methodology for implementation is SAP’s content-rich methodology for assisting with the implementation and/or upgrade of SAP solutions across industries and customer environments. Built on experience from thousands of SAP projects, ASAP provides content, tools, and best practices that help consultants to deliver consistent and successful results across industries and customer environments.

The six phases of ASAP provide support throughout the life cycle of SAP solutions. Underlying these phases is a series of value delivery checks to make sure that the solution, as implemented, delivers the expected value. Figure 4-6 illustrates the phases of ASAP.

Figure 4-6. The phases of ASAP.

The methodology covers key aspects of SAP implementation from project management guidance structured around the PMI PMBOK® Guide10 through business process design, business value management, application life-cycle management, organizational change management, technical solution management, data management, and other topics important for delivery of SAP solutions.

The ASAP methodology is not pure project management methodology, but instead it combines all key elements the project team needs to cover in order to deliver successful projects. This approach is shown in Figure 4-7.

Figure 4-7. The ASAP methodology elements.

The ASAP methodology is designed in a way that enables flexibility and scalability from smaller projects, such as single consulting services delivery, to more complex delivery of global deployments in multinational corporations. This flexible design allows us to use the methodology as a foundation for creation of all consulting services. Each engineered service leverages the common WBS of the ASAP methodology to define clearly the work that is performed, roles and skills that are required to deliver service, and also details about sourcing of the roles from within the organization.

This approach helps us achieve commonality between the services in areas that are not core expertise of service owners (like project management). It also lowers the cost of service creation and simplifies the adoption process.

Thanks to the use of common taxonomy based on ASAP in the creation of services, the SAP projects can be assembled from individual engineered services and delivered in assembled-to-order approach rather than designed from scratch. SAP was recognized by the Technology Services Industry Association in 2012 for its innovative approach in services delivery with the SAP Advanced Delivery Management approach that is built on principles of common modular services that can be assembled and reused in different projects. (See Figure 4-8.)

Figure 4-8. The new delivery approach

With this approach, SAP customers take advantage of prebuild services and content and lower the cost of deployment and complexity of projects and minimize the risk of deployment projects. The engineered services and rapid deployment solutions are used in early stages of the project to establish a baseline solution that is later enhanced in a series of iterative incremental builds using agile techniques. This innovative approach to project delivery has significantly changed the delivery of projects and requires our project managers to adopt their skills to this innovative way of project execution. One example is that project managers need to learn how to structure and run projects with the iterative agile techniques to design, configure, or develop customer-specific extensions, which is substantially different from traditional management of projects where solutions are built from scratch.

The common methodology and its taxonomy are not only great enablers for project delivery, but they have also helped SAP innovate the way solutions are delivered and deployed.

4.8 AIRBUS SPACE AND DEFENCE: INTEGRATED MULTILEVEL SCHEDULES11

Perhaps the single most important benefit of a good methodology is the ability to create integrated multilevel schedules for all stakeholders.

Why Integrated Multilevel Schedules?

The Integrated Multilevel Scheduling practice is aimed at providing each level of management of the project, from the Customer and/or the Company management, down to the Project Management, and down to the Work Package management, with consistent schedule baselines, consistent progress measurement, and consistent estimates to completion.

This practice is widely used for large and complex projects.

Definition of Integrated Multilevel Schedules

Project-integrated multilevel scheduling is aimed divided into three levels of management:

- Master schedule (Level 1): Customer and/or the company management

- Project summary schedule (Level 2): Project management

- Detailed schedule (Level 3): Work package management

By default, the different levels of schedules are self-sufficient, reflecting the delegation of management responsibility in the project:

- Master schedule is owned by the project manager.

- Project summary schedule is owned by the project manager (for large project, the project manager may be supported by the project management office).

- Detailed schedules are owned by work package managers.

In addition, to deliver and maintain a multilevel project schedule, links shall be performed between the different levels to provide an integrated multilevel project schedule.

Prerequisites to Prepare and to Deliver Integrated Multilevel Schedules

Before developing integrated multilevel schedules, the following deliverables shall be completed and performed:

Define the Project Scope

- Collect the requirements.

- Define the product breakdown structure with all internal and external deliverables.

- Develop the work breakdown structure—think deliverables.

- Specify work packages with a special focus on inputs needed and outputs expected including acceptance criteria of the deliverables.

- Plan a review of all the work packages descriptions with all main stakeholders of the project, the objective is to share and control the consistency between inputs and outputs of the different work packages.

- Estimate target duration, work, cost and skills for each work package.

- Manage risks and opportunities to define and plan mitigation actions and to identify where buffers shall be added in the plans.

Principles of Integrated Multilevel Schedules

The following principles shall be followed to ensure a success Integrated Multilevel Schedules:

- The master schedule (also called Level 1 Plan) shall deliver a synthetic view (one page) on the project schedule reflecting the major milestones (contractual milestones, major customer furnished items or equipment [CFI/CFE] with critical impact on contractual deliverables), the dependencies between major milestones and summaries of the main phases, the contractual dates (contract commitments), and the current contract status (major milestones passed and current progress with forecasted dates).

- The project summary schedule (also called Level 2 Plan) shall cover the complete WBS of the project and shall be organized according to the WBS structure. It shall provide the dependencies between all the WP of the project and the dependencies between the WP deliverables and the major milestones of the project.

- The detailed schedule (also called Level 3 Plan) shall deliver the detailed schedule of each work package, which shall be broken down in activities; each activity shall conduct to a deliverable and shall be broken down in elementary tasks with resources assigned.

In addition, between the different levels, multilevel schedule links shall be implemented (see Figure 4-9):

- Between the Level 1 Plan and the Level 2 Plan, links should be defined to follow the adherence to the contractual milestones dates (customer commitments) and other key milestones dates. Thereof, all major milestones (MM) reported in the Level 1 Plan shall be linked to corresponding MM in the Level 2 Plan.

- Between the Level 2 Plan and the Level 3 Plan, links should be defined to follow the adherence to the project dates (project target dates), where each WP, the input(s) and output(s) defined in the Level 2 Plan should be linked to corresponding input(s) and output(s) of the Level 3 Plan.

- Two types of links should be used:

- Hard links (also called driving links) for inputs in order to align automatically the date of availability of the corresponding input in the lower level.

- Soft links for outputs to inform on the forecasted date in the lower level of the output without impacting automatically the date defined in the upper level.

Figure 4-9. Example of integrated multilevel schedule.

Monitor and Control of Integrated Multilevel Schedules

The monitoring and controlling of the different levels of schedule, including the consistency, should be performed within one month according to the following scheme:

- Update of Level 3 schedules by each work package manager based on current actual and new forecast according to ongoing work package progress.

- Multilevel consistency checking by the project management office including the deviations and the identification of the impact over key milestones.

- Schedule review among project management office, engineering authority, and work package managers in order to identify actions plan to recover target dates.

Validation by the project manager with the update of Level 3 and Level 2 schedules based on the decisions taken and update performance baseline if needed.

4.9 TÉCNICAS REUNIDAS12

Material in this section has been provided by Felipe Revenga López, the chief operations officer of Técnicas Reunidas since September 2008. He joined Técnicas Reunidas in 2002 as project director and then as project sponsor of a group of international strategic projects. He has large experience in EPC-LSTK and OBE-LSTK projects in the Oil & Gas Production Units, Refining, Petrochemical, and Power Sector worldwide. He is an Industrial Engineer (specialty Chemicals) by the School of Industrial Engineers and currently is finishing the doctoral program in Engineering of Chemical and Biochemical Processes at the Polytechnic University of Madrid.

* * *

Introduction

Open Book Estimate as a Successful Contract Alternative to Execute Projects in the Oil and Gas Sector

As a result of the projected rate of energy demand growth, the oil and gas industry has a wide range of challenges and opportunities across different areas. For that reason, for a number of years the sector has been developing new facilities, which in many cases are megaprojects.

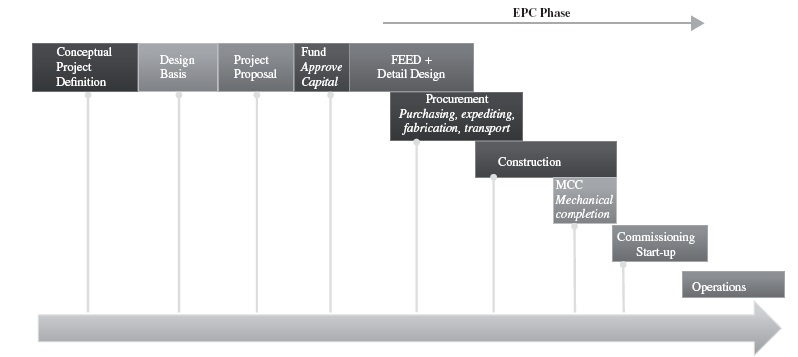

The typical complete life cycle of a capital project in the oil and gas sector is focused in the overall stages that are shown in Figure 4-10. Understanding and managing these stages is crucial on the long-term success of the project.

Figure 4-10. Typical life-cycle phases.

Lump-sum turnkey (LSTK) and cost-plus contracting are both very prevalent types of contracts within projects in the oil and gas industry. The level of risk the client of a project is willing to accept, budget constraints, and the client’s organization core competencies determine which method is best for a project.

A large number of projects in this sector are performed under engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC)–LSTK contracts; The major experience of Técnicas Reunidas (TR) is based mainly in this type of projects, which in general means managing the whole project and carrying out the detailed engineering (in some cases it is included the basic engineering or front-end engineering design (FEED) in the scope of work); procuring all the equipment and materials required; and then constructing, precommissioning, and starting up to deliver a functioning facility ready to operate. LSTK contracting tends to be riskiest, and all risks are assumed by the EPC contractor.

The open book estimate (OBE) or open book cost estimate (OBCE) is an alternative way to execute EPC projects. With this type of contract, the final purpose of the work is to define the total price of the project in collaboration with the client; the global costs of the project are established in a transparent manner (open book).

The Open Book Estimate

The main purpose of the OBE methodology is to build up an accurate EPC price by applying some parameters previously agreed on (between client and the contractor), the base cost through an OBE, the development of an extended front-end engineering effort and in some cases the placement of purchase orders for selected long lead and critical items to ensure the overall schedule of the project. The OBE will fix the project base cost and will become the basis for determining the lump-sum EPC price for the project.

During an OBE phase, the contractor develops a FEED and/or part of the detailed engineering under a reimbursable basis or lump-sum price or alternatives, including a complete and open cost estimate of the plant. After an agreed period (usually between 6 to 12 months, mainly dependent on the accuracy grade, schedule, and other factors required by client) of engineering development and after the client and contractor agree on the base cost, the contract is changed or converted to an EPC LSTK contract applying previously agreed-on multiplying factors.

Cost Estimate Methodology

Principal Cost Elements and Pricing Categories

The OBE usually is based on sufficient engineering development in accordance with the deliverables identified in OBE contract. These deliverables are developed as much as possible in the normal progress of the project. Required deliverables are prepared and submitted to the client prior to completion of the conversion phase.

The principal cost elements, as seen in Figure 4-11, that comprise the OBE are addressed below. The OBE cost estimate shall include the total scope of work:

- Detailed engineering, procurement, and construction services

- Supply of equipment, bulk materials, and spare parts

- Transport to construction site

- Customs clearance

- Construction and erection at site

- Provision of subcontractors’ temporary construction facilities and services

- Construction and precommissioning services

- Commissioning and start-up services

- Training services and vendor’s assistance

- Bonds, insurances, hedging charges

- Other costs, including third-party inspection and contractor insurance

- Others

Figure 4-11. Typical cost elements.

Cost Base

- An OBE procedure is developed during the contract stage and implemented during the project’s OBE phase. All details on how to prepare an OBE have to be agreed and included as an annex in the contract.

- Preagreement of allowances, growth, conditioning, technical design allowances, surplus, and cut and waste.

- Material take-offs (MTOs) based on PDS software, measured in process and instrument diagrams (P&ID) and plot plans and estimates. All details on procedures are to be agreed on before OBE contract signature.

In executing projects under convertible basis, TR develops the OBE in parallel with the normal project execution, ensuring that both activities can flow smoothly without interference. During the OBE phase, in certain cases and if agreed with the client, TR can advance the procurement of the main equipment and initiate negotiations for construction subcontractors. The execution of these activities in advance facilitates the fulfillment of project schedule requirements.

This OBE phase of the project is jointly developed between the client and TR. The OBE is fully transparent to client and the conversion to LSTK is made once the risk/reward element is fixed.

In Figure 4-12, we see the main steps and activities that are developed to achieve OBE goals and to convert to next phase of the project.

Figure 4-12. Steps to achieve OBE target.

During the OBE phase, cost-saving ideas are developed in order to adjust the final cost estimate; to do so, a special team of engineering specialists is appointed to work with both the engineering manager and the estimating manager, with the purpose to determine those areas where potential savings can be achieved by optimizing the design, without jeopardizing safety, quality, or schedule. Any of these changes that could lead to cost savings are carefully evaluated from a technical point of view. If the feasibility of the potential change is proven, the alternative solution, together with the cost-saving impact evaluation, will be forwarded to the clients for consideration.

The EPC contract price is the result of the base cost multiplied by fixed percentages for fee and markups related to equipment, bulk materials, construction, and ancillary costs agreed to by the client and contractor. During the conversion phase, this price is converted to lump-sum price and thereafter remains fixed during the EPC-LSTK phase.

Contracts

There are two typical models of contracts under this OBE alternative:

- One contract, two parts: OBE and EPC. The price for the EPC part is to be included at conversion.

- Two contracts, one OBE and the other EPC. Both may be signed at the beginning or one at the beginning and the other at conversion.

The methodology of the OBE is included in the contract.

In the case of no conversion:

- The contractual relationship disappears, and both client and contractor break their commitment. The client may break the contract if it is not interested. Consequences:

- Six months for a new LSTK offer. Two to three months plus evaluating the offers

- Repeat FEED with different contractor.

- Contract provides mechanisms in the case of no agreement.

- Continue contract on a service base (better LS contract).

- Agree on partial conversion.

- Other actions as per contract agreement.

Advantages

An OBE phase followed by an LSTK contract could optimize all project execution, especially in cost and schedule.

- In terms of cost, the client and contractor could together determine the project cost through an OBCE because an estimation methodology, conversion conditions such as multiplying factors are agreed upon, etc. Both the client and the contractor determine by mutual agreement the final price of the contract, sharing all information. This will generate a feeling of trust between both companies. This model results in an accurate cost because unnecessary contingencies are avoided.

- However, this model results in schedule advantages because the bidding period is shortened or replaced by a conversion negotiation phase; an EPC stage is shortened because all the work is developed during the extended feed and conversion stage. A representation of the schedule advantage is shown in Figure 4-13.

Figure 4-13. Typical schedule advantage.

In summary, the advantages in cost and schedule are shown in Table 4-2.

TABLE 4-2 COST AND SCHEDULE ADVANTAGES OF THE OBE METHODOLOGY

| Cost | Schedule Reduction |

|

Develops an EPC estimate during 6 to 12 months. This provides a much more accurate costs. Accurate prices based on real offers and an agreed conversion factor assures fairness to client and contractor. There is enough time to develop the project and to avoid unnecessary contingencies. Application of cost saving to match project cost to client’s budget. Facilitates the possibility of funding, because a more accurate estimation. Risk are reduced and better controlled to the benefit of both client and contractor |

Short bidding period, as cost estimate does not need to be as detailed in an EPC-LSTK common bidding process Shortening of the overall project schedule: time for extended FEED and EPC bidding is shortened dramatically. Contract award procedure is much easier and shorter. Some long-lead Items and critical equipment could be awarded or negotiated. |

Close-out

The OBE has been demonstrated to be a successful contract alternative for executing projects in the oil and gas sector because it aligns clients and contractors with the project’s goals. Both are motivated to pursue the best cost estimation or project target cost, and at the same time the schedule is optimized.

As mentioned in the introduction to this section, in the oil and gas sector, most current projects can be considered megaprojects, where there are many risks with a high workload from suppliers, contractors, subcontractors, and others. Through an OBE alternative, clients can better manage risks through a more cooperative and agreed-on approach, where the risks are reduced during an accurate estimate and then embraced rather than totally transferred to contractors. In this way, project outcomes can be improved.

TR has converted successfully 100 percent from OBE to EPC-LSTK projects.

Definitions

- Client: The owner of the oil and gas company

- Contractor: Affiliated company responsible for performing the engineering, procurement and construction services

- EPC: Engineering, procurement, and construction. Type of contract typical of industrial plant construction sector, comprising the provision of engineering services, procurement of materials, and construction.

- FEED: Front-end engineering design. This refers to basic engineering conducted after completion of the conceptual design or feasibility study. At this stage, before the start of EPC, various studies take place to figure out technical issues and estimate rough investment cost.

- LS contract: Lump-sum contract. In a lump-sum contract, the contractor agrees to do a specific project for a fixed price

- LSTK contract: lump-sum contract. In a lump-sum turnkey contract, all systems are delivered to the client ready for operations.

- MTOS: Material take-offs. This refers to piping, electrical, and instrumentation.

- OBE: Open book estimate or open book cost estimate (OBCE)

- PDS: Plant design system. Software used for designing industrial plants through a multidisciplinary engineering activity

- P&ID: Process and instrument diagrams

- TR: Técnicas Reunidas

4.10 YANFENG GLOBAL AUTOMOTIVE INTERIOR SYSTEMS CO. LTD.13

The Product Realization Process (PRP) project was a global initiative to develop a common launch process to enable consistent execution across all regions within the organization. The project team of regional subject matter experts in all functions worked collaboratively to develop a standard set of deliverables and timing objectives for every program launch. Training was also developed to support the roll-out of the process. The PRP project charter, approved by the organization leadership, allowed the project team to develop a common launch process that would be applied globally. An aggressive target required the process to be ready to support implementation on programs, in a pilot phase, within six months. PRP enables our new company to “speak one language” regarding program development and launch.

The PRP project team succeeded in developing the new process within the targeted six-month period and made the process available for release into internal systems by October 2016. The core PRP Project team consisted of experienced subject matter experts from each region and each functional group. In total, this was over 30 members.

Initial project development activity began with Workshop #1 in August 2016 in Holland, Michigan, and completed five months later in Shanghai with Workshop #4 in December 2016. Functional experts from North America, Europe, and Asia Pacific regions participated in multiple workshop activities, in addition to their regular work duties. Significant effort was also extended between workshops to continue collaboration and help ensure global alignment on functional deliverable requirements.

The PRP team members also helped develop functional training material to support PRP Pilot phase activity. Training was provided in e-learning, video, and classroom style. Pilot phase team training was kicked off in February 2016. Over 200 team members across the three global regions participated in PRP training for their pilot programs. Over 30 PRP pilot teams used the PRP launch process.

Through the course of the workshop activity and cross-functional collaboration, over 100 process documents were developed and released.

The result of this tremendous effort by a global team is the availability of a common process that will enable consistent launch execution in all regions and allow for seamless execution of global programs. The PRP project team achieved the requirements established in the project charter.

The PRP project team demonstrated all of the organization’s values over the course of the six-month project. The process, created by the team, will positively impact future programs for many years.

This project required that an experienced cross-functional team worked together across different regions, cultures, and time zones. The team was united by one vision to create a new common process based on prior JCI-PLUS and YF-IDS launch processes. Each functional group demonstrated exceptional teamwork working collaboratively with regional peer groups. Team collaboration was highly visible within working groups as they focused on understanding unique regional requirements.

Team members assumed this activity and additional responsibilities beyond their normal work activities. This required extensive travel and additional support that exceeded normal working hours. Each team member stayed focused and fully committed to meet project deliverables. The multicultural team remained patient and open to learning from each other and developing a world-class launch process.

Functional group leaders and individuals consistently demonstrated personal initiative, accountability, and a passion for excellence. Action plans were developed and executed to accomplish the overall project objectives and timeline. Each team member recognized the significance of this project and the long-term benefit to Yanfeng Global Automotive Interior Systems (YFAI).

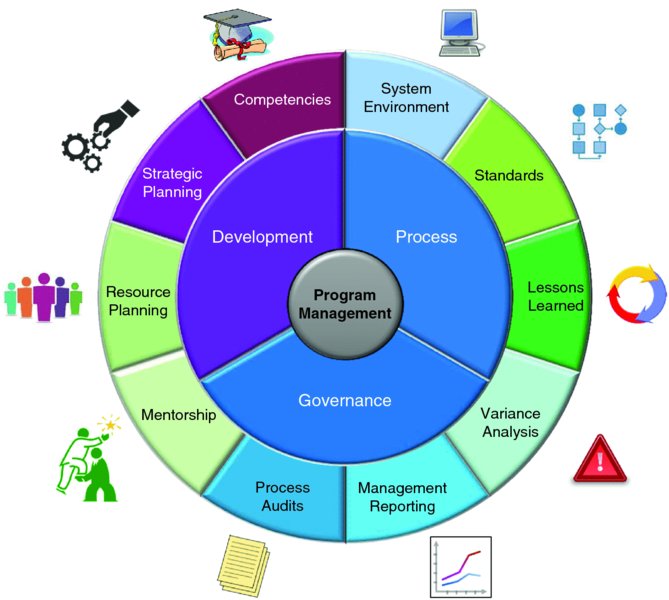

Facilitating a standard process for launching programs is only one element within the realm of responsibility for the program management office. The governance of process and compliance along with the development of program team members are the other two areas that are the focus for the project management office (see Figure 4-14).

Figure 4-14. Major Components of Program Management.

The true best practice of developing and institutionalizing the new PRP is that it was managed as an actual project using the typical methods of project management. The project timing was managed by the use of a standard timeline and Gantt charts. All of the PMBOK knowledge areas were integrated, and project success was enabled by utilizing the processes of initiation, planning, execution, monitoring, and closing.

4.11 SONY CORPORATION AND EARNED VALUE MANAGEMENT14

Earned value management (EVM) is one of the most commonly used tools in project management. When it is used correctly, EVM becomes a best practice and allows managers and executives to have a much clearer picture as to the true health of a project. EVM can also lead to significant continuous improvement efforts. Such was the case at Sony.

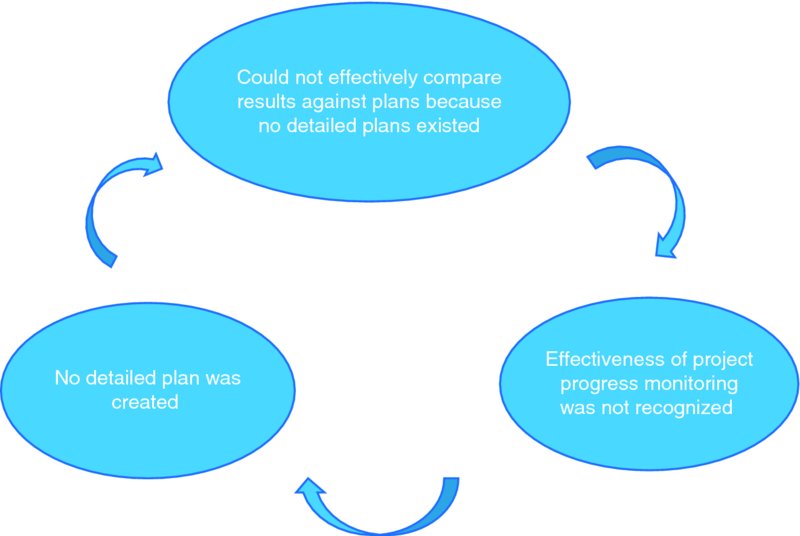

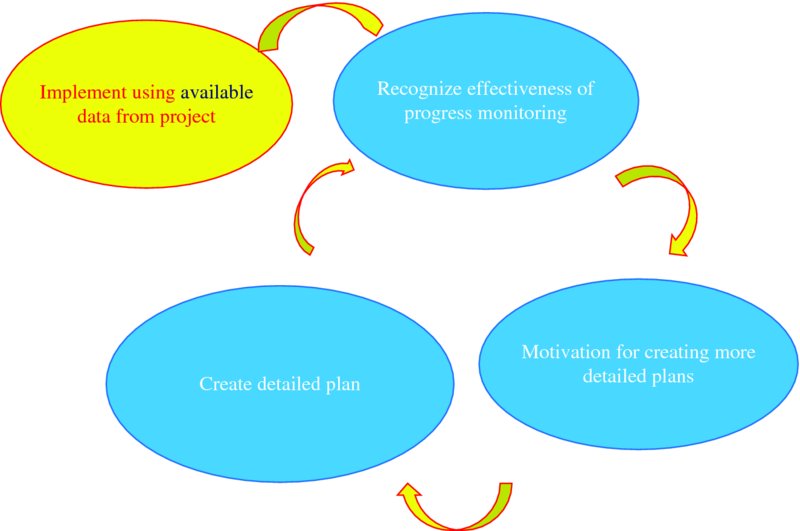

Sony suffered from some of the same problems that were common in other companies. Because project planning at Sony often did not have desired level of detail, Sony viewed itself as operating in a “negative cycle,” as shown in Figure 4-15. Sony’s challenge was to come up with effective and sustainable ways to break out of this negative cycle.

Figure 4-15. Sony’s negative cycle.

Sony’s basic idea or assumption was that unless people recognize the need for change and want to get involved, nothing will happen, let alone further improvements. Sony realized that, at the beginning of the EVM implementation process, it might need to sacrifice accuracy of the information.

Sony sought the easiest possible or the most elementary way for project managers and team members to implement progress monitoring continuously.

Sony started by:

- Using information on a list of final deliverables together with a completion date for each final deliverable. Team members did not have to make an extra effort to produce this level of information because it was being provided to them.

- Selecting the fixed ratio method, among several EVM methods, such as the weighted milestone method, percentage-complete method, and criteria achievement method for reporting progress. The fixed ratio method required the least effort from project managers and team members.

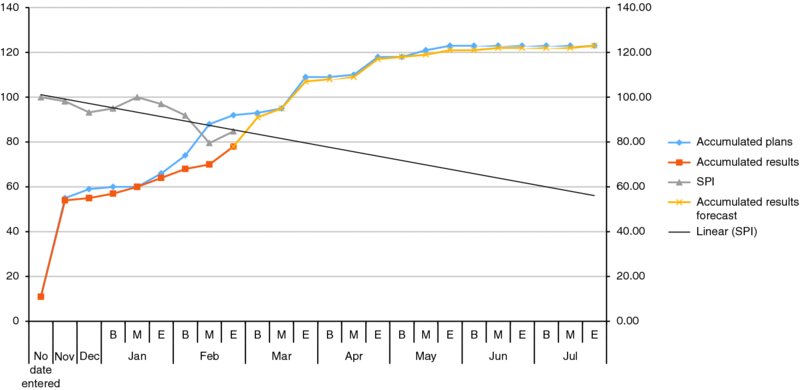

- Visualizing project progress and monitoring process using various graphs, such as Figures 4-16 and 4-17 for Schedule Performance Index (SPI) reporting.

Figure 4-16.. SPI (progress rate) transition by team.

Figure 4-17.. Overall project progress forecasting (linear approximation).

Shortly after people started to practice this elementary method of progress monitoring and reporting, we began to observe the following improvements:

- Increased awareness by project managers and team members that forecasting, early alerts, and taking countermeasures earlier improve productivity (i.e., SPI).

- Increased awareness by project managers and team members that reviewing and creating more detailed plans were critical to further improve productivity (i.e., SPI).

Visualization or performance certainly helped the project teams to easily understand how important and beneficial practicing project progress monitoring was.

Project managers and team members began to take initiatives to improve project progress monitoring and reporting, as shown in Figure 4-18. For example, team members noted that delays in progress were difficult to detect when data accuracy was poor or not detailed enough. Team members started to improve data accuracy by:

- Dividing a month into three parts. Previously, data was given on a monthly basis.

- Making changes to the fixed ratio method. Previously, the 1/100 rule had been applied but now the 20/80 rule was used.

- Adding intermediate deliverables. Intermediate deliverables were reported in addition to final deliverables

Figure 4-18.. The progress improvement cycle.

In summary, as an effective first step toward implementing progress monitoring, it is important to start by using as data whatever deliverables are already available in your organization.

By visualizing progress monitoring and through forecasting, ensure sure that correct countermeasures are taken to solve problems.

Accuracy will be improved once people become aware of the effectiveness of project progress monitoring.

Reference Documents

Nagachi, Koichi. 2006. “PM Techniques Applied in Nile Firmware Development: An Attempt to Visualize Progress by EVM.” Paper presented at the PMI Tokyo Forum.

Nagachi, Koichi, and Jun Makino. 2012. “Practicing Three Earned Value Measurement Methods.” Paper presented at the PMI Japan Forum.

Tominaga, Akira. August 20, 2003. EVM: Earned Value Management for Japan. Society of Project Management.

Yamato, Shoso, and Koichi Nagachi. April 20, 2009. “IT Project Management by WBS/EVM,” Soft Research Center Inc.

4.12 PROJECT MANAGEMENT TOOLS AND SOCIALIZED PROJECT MANAGEMENT

In the early years of project management, EVM was the only tool used by many companies. Customers such as the Department of Defense created standardized forms that every contractor was expected to complete for performance reporting. Some companies had additional tools, but these were for internal use only and not to be shared with the customers.

As project management evolved, companies created enterprise project management (EPM) methodologies that were composed of multiple tools displayed as forms, guidelines, templates, and checklists. The tools were designed to increase the chances of repeatable project success and designed such that they could be used on multiple projects. Ideas for the additional tools often came from an analysis of best practices and lessons learned captured at the end of each project. Many of the new tools came from best practices learned from project mistakes such that the mistakes would not be repeated on future projects. Project teams now could have as many as 50 different tools to be used. Some tools were used for:

- Defining project success since the definition could change from project to project

- Capturing best practices and lessons learned throughout the project life cycle rather than just at project completion

- Advances in project performance reporting techniques

- Capturing benefits and value throughout the life cycle of the project

- Measuring customer satisfaction throughout the life cycle of the project

- Handing off project work to other functional groups

As project management continued to evolve, companies moved away from co-located teams to distributed or virtual teams. Now additional tools were needed to help support the new forms of project communications that would be required. Project managers were now expected to communicate with everyone, including stakeholders, rather than just project team members. Some people referred to this as PM 2.0, where the emphasis was on social project management practices.

Advances in technology led to a growth in collaborative software, such as Facebook, and Twitter, as well as collaborative communications, platforms such as company intranets. New project management tools, such as dashboard reporting systems, would be needed. Project management was undergoing a philosophical shift away from centralized command and control to socialized project management, and additional tools were needed for effective communications. These new tools are allowing for a more rigorous form of project management to occur accompanied by more accurate performance reporting. The new tools also allow for decision making based on facts and evidence rather than guesses.

4.13 ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND PROJECT MANAGEMENT

It appears that the world of artificial intelligence (AI) is now entering the project management community of practice, and there is significant interest in this topic. Whether AI will cause an increase or decrease in project management tools is uncertain, but an impact is expected.

A common definition of AI is intelligence exhibited by machines.15 From a project management perspective, could a machine eventually mimic the cognitive functions associated with the mind of a project manager such as decision making and problem solving? The principles of AI are already being used in speech recognition systems and search engines, such as Google Search and Siri. Self-driving cars use AI concepts as do military simulation exercises and content delivery networks. Computers can now defeat most people in strategy games such as chess. It is just a matter of time before we see AI techniques involved in project management.

The overall purpose of AI is to create computers and machinery that can function in an intelligent manner. Doing this requires the use of statistical methods, computational intelligence, and optimization techniques. The programming for such AI techniques requires not only an understanding of technology but also an understanding of psychology, linguistics, neuroscience, and many other knowledge areas.

The question regarding the use of AI is whether the mind of a project manager can be described so precisely that it can be simulated using the techniques just described. Perhaps there is no simple logic that will accomplish this in the near term, but there is hope because of faster computers, the use of cloud computing, and increases in machine learning technology. However, there are some applications of AI that could assist project managers in the near term:

- The growth in the use of competing constraints rather than the traditional triple constraints will make it more difficult to perform trade-off analyses. The use of AI concepts could make life easier for project managers.

- We tend to take it for granted that the assumptions and constraints given to us at the onset of the project will remain intact throughout the project’s life cycle. Today, we know that this is not true and that all assumptions and constraints must be tracked throughout the life cycle. AI could help us in this area.

- Executives quite often do not know when to intervene in a project. Many companies today are using crises dashboards. When an executive looks at the crises dashboard on the computer, the display identifies only those projects that may have issues, which metrics are out of the acceptable target range, and perhaps even the degree of criticality. AI practices could identify immediate actions that could be taken and thus shorten response time to out-of-tolerance situations.

- Management does not know how much additional work can be added to the queue without overburdening the labor force. For that reason, projects are often added to the queue with little regard for (1) resource availability, (2) skill level of the resources needed, and (3) the level of technology needed. AI practices could allow for the creation of a portfolio of projects that has the best chance to maximize the business value the firm will receive while considering effective resource management practices.

- Although some software algorithms already exist for project schedule optimization, practices still seem to be a manual activity using trial-and-error techniques. Effective AI practices could make schedule optimization significantly more effective by considering all present and future projects in the company rather than just individual projects.