17

Effect of Mergers and Acquisitions on Project Management

17.0 INTRODUCTION

All companies strive for growth. Strategic plans are prepared identifying new products and services to be developed and new markets to be penetrated. Many of these plans require mergers and acquisitions to obtain the strategic goals and objectives. Yet even the best-prepared strategic plans often fail. Too many executives view strategic planning as planning only, often with little consideration given to implementation. Implementation success is vital during the merger and acquisition process.

17.1 PLANNING FOR GROWTH

Companies can grow in two ways: internally and externally. With internal growth, companies cultivate their resources from within and may spend years attaining their strategic targets and marketplace positioning. Since time may be an unavailable luxury, meticulous care must be given to make sure that all new developments fit the corporate project management methodology and culture.

External growth is significantly more complex. External growth can be obtained through mergers, acquisitions, and joint ventures. Companies can purchase the expertise they need very quickly through mergers and acquisitions. Some companies execute occasional acquisitions, whereas other companies have sufficient access to capital such that they can perform continuous acquisitions. However, once again, companies often fail to consider the impact of acquisitions on project management. Best practices in project management may not be transferable from one company to another. The impact on project management systems resulting from mergers and acquisitions is often irreversible, whereas joint ventures can be terminated.

Effect of Mergers and Acquisitions on Project Management

This chapter focuses on the impact on project management resulting from mergers and acquisitions. Mergers and acquisitions allow companies to achieve strategic targets at a speed not easily achievable through internal growth, provided that the sharing of assets and capabilities can be done quickly and effectively. This synergistic effect can produce opportunities that a firm might be hard-pressed to develop itself.

Mergers and acquisitions focus on two components: preacquisition decision making and postacquisition integration of processes. Wall Street and financial institutions appear to be interested more in the near-term financial impact of acquisitions than the long-term value that can be achieved through better project management and integrated processes. During the mid-1990s, companies rushed into acquisitions in less time than they required for capital expenditure approvals. Virtually no consideration was given to the impact on project management and whether the expected best practices would be transferable. As a result, there have been more failures than successes.

When a firm rushes into an acquisition, very little time and effort appear to be spent on postacquisition integration. Yet this is where the real impact of best practices is felt. Immediately after an acquisition, each firm markets and sells products to the other’s customers. This may appease the stockholders, but only in the short term. In the long term, new products and services will need to be developed to satisfy both markets. Without an integrated project management system where both parties can share the same best practices, this may be difficult to achieve.

When sufficient time is spent on preacquisition decision making, both firms look at combining processes, sharing resources, transferring intellectual property, and the overall management of combined operations. If these issues are not addressed in the preacquisition phase, unrealistic expectations may occur during the postacquisition integration phase.

17.2 PROJECT MANAGEMENT VALUE-ADDED CHAIN

Mergers and acquisitions are expected to add value to the firm and increase its overall competitiveness. Some people define value as the ability to maintain a certain revenue stream. A better definition of value might the competitive advantages that a firm possesses as a result of customer satisfaction, lower cost, efficiencies, improved quality, effective utilization of personnel, or the implementation of best practices. True value occurs only in the postacquisition integration phase, well after the actual acquisition itself.

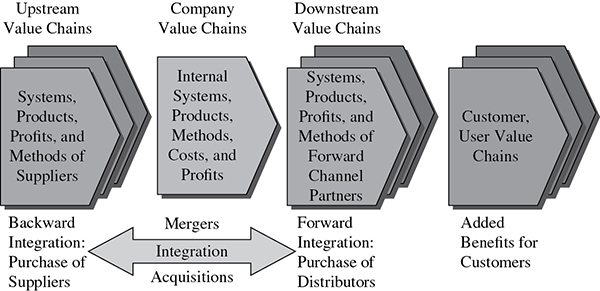

Value can be analyzed by looking at the value chain: the stream of activities from upstream suppliers to downstream customers. Each component in the value chain can provide a competitive advantage and enhance the final deliverable or service. Every company has a value chain, as illustrated in Figure 17-1. When a firm acquires a supplier, the value chains are combined and expected to create a superior competitive position. Similarly, the same result is expected when a firm acquires a downstream company. But it may not be possible to integrate the best practices.

Figure 17-1. Generic value-added chain.

Historically, value chain analysis was used to look at a business as a whole.1 However, for the remainder of this chapter, the sole focus will be the project management value-added chain and the impact of mergers and acquisitions on the performance of the chain.

Figure 17-2 shows the project management value-added chain. The primary activities are those efforts needed for the physical creation of a product or service. The primary activities can be considered to be the five major process areas of project management: project initiation, planning, execution, control, and closure.

Figure 17-2. Project management value-added chain.

The support activities are those company-required efforts needed for the primary activities to take place. At an absolute minimum, the support activities must include:

- Procurement management. The quality of the suppliers and the products and services they provide to the firm.

- Effect of mergers and acquisitions on project management. The ability to combine multiple project management approaches, each at a different level of maturity.

- Technology development. The quality of the intellectual property controlled by the firm and the ability to apply it to products and services both offensively (new product development) or defensively (product enhancements).

- Human resource management. The ability to recruit, hire, train, develop, and retain project managers. This includes the retention of project management intellectual property.

- Supportive infrastructure. The quality of the project management systems necessary to integrate, collate, and respond to queries on project performance. Included within the supportive infrastructure are the project management methodology, project management information systems, total quality management system, and any other supportive systems. Since customer interfacing is essential, the supportive infrastructure can also include processes for effective supplier–customer interfacing.

These support activities can be further subdivided into nine of the 10 knowledge areas of the PMBOK® Guide. The arrows connecting the nine PMBOK® Guide areas indicate their interrelatedness. The exact interrelationships may vary for each project, deliverable, and customer (Figure 17-2)

Each of these primary and support activities, together with the nine process areas, is required to convert material received from your suppliers into deliverables for your customers. In theory, Figure 17-2 represents a work breakdown structure for a project management value-added chain:

- Level 1: Value chain

- Level 2: Primary activities

- Level 3: Support activities (which can include the Stakeholder Management knowledge area)

- Level 4: Nine of the 10 PMBOK® Guide knowledge areas

The project management value-added chain allows a firm to identify critical weaknesses where improvements must take place. This could include better control of scope changes, the need for improved quality, more timely status reporting, better customer relations, or better project execution. The value-added chain can also be useful for supply chain management. The project management value-added chain is a vital tool for continuous improvement efforts and can easily lead to the identification of best practices.

Executives regard project costing as a critical, if not the most critical, component of project management. The project management value chain is a tool for understanding a project’s cost structure and the cost control portion of the project management methodology. In most firms, this is regarded as a best practice. Actions to eliminate or reduce a cost or schedule disadvantage need to be linked to the location in the value chain where the cost or schedule differences originated.

The glue that ties together elements within the project management chain is the project management methodology. A project management methodology is a grouping of forms, guidelines, checklists, policies, and procedures necessary to integrate the elements within the project management value-added chain. A methodology can exist for an individual process, such as project execution, or for a combination of processes. A firm can also design its project management methodology for better interfacing with upstream or downstream organizations that interface with the value-added chain. Ineffective integration at supplier–customer interface points can have a serious impact on supply chain management and future business.

17.3 PREACQUISITION DECISION MAKING

The reason for most acquisitions is to satisfy a strategic and/or financial objective. Table 17-1 shows the six most common reasons for an acquisition and the most likely strategic and financial objectives. The strategic objectives are somewhat longer term than the financial objectives that are under pressure from stockholders and creditors for quick returns.

TABLE 17-1 TYPES OF OBJECTIVES

| Reason for Acquisition | Strategic Objective | Financial Objective |

| Increase customer base | Bigger market share | Bigger cash plow |

| Increase capabilities | Provide solutions | Wider profit margins |

| Increase competitiveness | Eliminate costly steps | Stable earnings |

| Decrease time to market (new products) | Market leadership | Earnings growth |

| Decrease time to market (enhancements) | Broad product lines | Stable earnings |

| Closer to customers | Better price–quality–service mix | Sole-source procurement |

The long-term benefits of mergers and acquisitions include:

- Economies of combined operations

- Assured supply or demand for products and services

- Additional intellectual property, which may have been impossible to obtain otherwise

- Direct control over cost, quality, and schedule rather than being at the mercy of a supplier or distributor

- Creation of new products and services

- Pressure on competitors through the creation of synergies

- Cost cutting by eliminating duplicated steps

Each of these can generate a multitude of best practices.

The essential purpose of any merger or acquisition is to create lasting value that becomes possible when two firms are combined and value exists that would not exist separately. The achievement of these benefits, as well as attainment of strategic and financial objectives, could rest on how well the project management value-added chains of both firms integrate, especially the methodologies within their chains. Unless the methodologies and cultures of both firms can be integrated, and reasonably quickly, the objectives may not be achieved as planned.

Project management integration failures occur after the acquisition happens. Typical failures are shown in Figure 17-3. These common failures result because mergers and acquisitions simply cannot occur without organizational and cultural changes that are often disruptive in nature. Best practices can be lost. It is unfortunate that companies often rush into mergers and acquisitions with lightning speed but with little regard for how the project management value-added chains will be combined. Planning for better project management should be of paramount importance, but unfortunately is often lacking.

Figure 17-3. Project management problem areas after an acquisition.

The first common problem area in Figure 17-3 is the inability to combine project management methodologies within the project management value-added chains. This occurs because of:

- A poor understanding of each other’s project management practices prior to the acquisition

- No clear direction during the preacquisition phase on how the integration will take place

- Unproven project management leadership in one or both of the firms

- A persistent attitude of “we–them”

Some methodologies may be so complex that a great amount of time is needed for integration to occur, especially if each organization has a different set of clients and different types of projects. As an example, a company developed a project management methodology to provide products and services for large publicly held companies. The company then acquired a small firm that sold exclusively to government agencies. The company realized too late that integration of the methodologies would be almost impossible because of requirements imposed by government agencies for doing business with the government. The methodologies were never integrated, and the firm servicing government clients was allowed to function as a subsidiary, with its own specialized products and services. The expected synergy never occurred.

Some methodologies simply cannot be integrated. It may be more prudent to allow the organizations to function separately than to miss windows of opportunity in the marketplace. In such cases, pockets of project management may exist as separate entities throughout a large corporation.

The second major problem area in Figure 17-3 is the existence of differing cultures. Although project management can be viewed as a series of related processes, it is the working culture of the organization that must eventually execute these processes. Resistance by the corporate culture to support project management effectively can cause the best plans to fail. With opposing cultures, there may be differences in the degree to which each:

- Has (or does not have) management expertise (i.e., missing competencies)

- Resists change

- Resists technology transfer

- Resists transfer of any type of intellectual property

- Allows for a reduction in cycle time

- Allows for the elimination of costly steps

- Insists on reinventing the wheel

- Perceives project criticism as personal criticism

Integrating two cultures can be equally difficult during both favorable and unfavorable economic times. People may resist any changes in their work habits or comfort zones, even when they recognize that the company will benefit by the changes.

Multinational mergers and acquisitions are equally difficult to integrate because of cultural differences. Ten years ago, a U.S. automotive supplier acquired a European firm. The American company supported project management vigorously and encouraged its employees to become certified in project management. The European firm provided very little support for project management and discouraged its workers from becoming certified, using the argument that European clients do not regard project management in such high esteem as do General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler. The European subsidiary saw no need for project management. Unable to combine the methodologies, the U.S. parent company slowly replaced the European executives with American executives to drive home the need for a single project management approach across all divisions. It took almost five years for the complete transformation to take place. The parent company believed that the resistance in the European division was more of a fear of change in its comfort zone than a lack of interest by its European customers.

Sometimes there are clear indications that the merging of two cultures will be difficult. When Federal Express acquired Flying Tiger in 1988, the strategy was to merge the two into one smoothly operating organization. At the time of the merger, Federal Express (since renamed FedEx Express) employed a younger workforce, many of whom were part time. Flying Tiger had full-time, older, longer-tenured employees. FedEx focused on formalized policies and procedures and a strict dress code. Flying Tiger had no dress code, and management conducted business according to the chain of command, where someone with authority could bend the rules. Federal Express focused on a quality goal of 100 percent on-time delivery, whereas Flying Tiger seemed complacent with a 95 to 96 percent target. Combining these two cultures had to be a monumental task for Federal Express. In this case, even with these potential integration problems, Federal Express could not allow Flying Tiger to function as a separate subsidiary. Integration was mandatory. Federal Express had to address quickly those tasks that involved organizational or cultural differences.

Planning for cultural integration can also produce favorable results. Most banks grow through mergers and acquisitions. The general belief in the banking industry is to grow or be acquired. During the 1990s, National City Corporation of Cleveland, Ohio, recognized this and developed project management systems that allowed National City to acquire other banks and integrate the acquired banks into National City’s culture in less time than other banks allowed for mergers and acquisitions. National City viewed project management as an asset that has a very positive effect on the corporate bottom line. Many banks today have manuals for managing merger and acquisition projects

The third problem area in Figure 17-3 is the impact on the wage and salary administration program. The common causes of the problems with wage and salary administration include:

- Fear of downsizing

- Disparity in salaries

- Disparity in responsibilities

- Disparity in career path opportunities

- Differing policies and procedures

- Differing evaluation mechanisms

When a company is acquired and integration of methodologies is necessary, the impact on the wage and salary administration program can be profound. When an acquisition takes place, people want to know how they will benefit individually, even though they know that the acquisition is in the best interest of the company.

The company being acquired often has the greatest apprehension about being lured into a false sense of security. Acquired organizations can become resentful to the point of physically trying to subvert the acquirer. This will result in value destruction, where self-preservation becomes of paramount importance to the workers, often at the expense of the project management systems.

Consider the following situation. Company A decided to acquire company B. Company A has a relatively poor project management system in which project management is a part-time activity and not regarded as a profession. Company B, in contrast, promotes project management certification and recognizes the project manager as a full-time, dedicated position. The salary structure for the project managers in company B is significantly higher than for their counterparts in company A. The workers in company B expressed concern that “We don’t want to be like them,” and self-preservation led to value destruction.

Because of the wage and salary problems, company A tried to treat company B as a separate subsidiary. But when the differences became apparent, project managers in company A tried to migrate to company B for better recognition and higher pay. Eventually, the pay scale for project managers in company B became the norm for the integrated organization.

When people are concerned with self-preservation, the short-term impact on the combined value-added project management chain can be severe. Project management employees must have at least the same, if not better, opportunities after acquisition integration as they did prior to the acquisition.

The fourth problem area in Figure 17-3 is the overestimation of capabilities after acquisition integration. Included in this category are:

- Missing technical competencies

- Inability to innovate

- Speed of innovation

- Lack of synergy

- Existence of excessive capability

- Inability to integrate best practices

Project managers and those individuals actively involved in the project management value-added chain rarely participate in preacquisition decision making. As a result, decisions are made by managers who may be far removed from the project management value-added chain and whose estimates of postacquisition synergy are overly optimistic.

The president of a relatively large company held a news conference announcing that his company was about to acquire another firm. To appease the financial analysts attending the news conference, he meticulously identified the synergies expected from the combined operations and provided a timeline for new products to appear on the marketplace. This announcement did not sit well with the workforce, who knew that the capabilities were overestimated and that the dates were unrealistic. When the product launch dates were missed, the stock price plunged, and blame was placed, erroneously, on the failure of the integrated project management value-added chain.

The fifth problem area in Figure 17-3 is leadership failure during postacquisition integration. Included in this category are:

- Leadership failure in managing change

- Leadership failure in combining methodologies

- Leadership failure in project sponsorship

- Overall leadership failure

- Invisible leadership

- Micromanagement leadership

- Believing that mergers and acquisitions must be accompanied by major restructuring

Managed change works significantly better than unmanaged change. Managed change requires strong leadership, especially with personnel experienced in managing change during acquisitions.

Company A acquires company B. Company B has a reasonably good project management system but with significant differences from company A. Company A then decides, “We should manage them like us,” and nothing should change. Company A then replaces several company B managers with experienced company A managers. This change occurred with little regard for the project management value-added chain in company B. Employees within the chain in company B were receiving calls from different people, most of whom were unknown to them, and were not provided with guidance on whom to contact when problems arose.

As the leadership problem grew, company A kept transferring managers back and forth. This resulted in smothering the project management value-added chain with bureaucracy. As expected, performance was diminished rather than enhanced.

Transferring managers back and forth to enhance vertical interactions is an acceptable practice after an acquisition. However, it should be restricted to the vertical chain of command. In the project management value-added chain, the main communication flow is lateral, not vertical. Adding layers of bureaucracy and replacing experienced chain managers with personnel inexperienced in lateral communications can create severe roadblocks in the performance of the chain.

Any of the problem areas, either individually or in combination with other problem areas, can cause the chain to have diminished performance, such as:

- Poor deliverables

- Inability to maintain schedules

- Lack of faith in the chain

- Poor morale

- Trial by fire for all new personnel

- High employee turnover

- No transfer of project management intellectual property

17.4 LANDLORDS AND TENANTS

Previously, it was shown how important it is to assess the value chain, specifically the project management methodology, during the preacquisition phase. No two companies have the same value chain for project management or the same best practices. Some chains function well; others perform poorly.

For simplicity sake, the “landlord” will be the acquirer and the “tenant” will be the firm being acquired. Table 17-2 identifies potential high-level problems with the landlord–tenant relationship as identified in the preacquisition phase. Table 17-3 shows possible postacquisition integration outcomes.

TABLE 17-2 POTENTIAL PROBLEMS WITH COMBINING METHODOLOGIES BEFORE ACQUISITIONS

| Landlord | Tenant |

| Good methodology | Good methodology |

| Good methodology | Poor methodology |

| Poor methodology | Good methodology |

| Poor methodology | Poor methodology |

TABLE 17-3 POSSIBLE INTEGRATION OUTCOMES

| Methodology | ||

| Landlord | Tenant | Possible Results |

| Good | Good | Based on flexibility, good synergy achievable; market leadership possible at a low cost |

| Good | Poor | Tenant must recognize weaknesses and be willing to change; possible culture shock |

| Poor | Good | Landlord must see present and future benefits; strong leadership essential for quick response |

| Poor | Poor | Chances of success limited; good methodology may take years to get |

The best scenario occurs when both parties have good methodologies and, most important, are flexible enough to recognize that the other party’s methodology may have desirable features. Good integration here can produce a market leadership position.

If the landlord’s approach is good and the tenant’s approach is poor, the landlord may have to force a solution on the tenant. The tenant must be willing to accept criticism, see the light at the end of the tunnel, and make the necessary changes. The changes, and the reasons for the changes, must be articulated carefully to the tenant to avoid culture shock.

Quite often a company with a poor project management methodology will acquire an organization with a good approach. In such cases, the transfer of project management intellectual property must occur quickly. Unless the landlord recognizes the achievements of the tenant, the tenant’s value-added chain can diminish in performance and there may be a loss of key employees.

The worst-case scenario occurs when neither the landlord nor the tenant has a good project management system. In this case, all systems must be developed anew. This could be a blessing in disguise because there may be no hidden bias by either party.

17.5 SOME BEST PRACTICES WHEN COMPANIES WORK TOGETHER

The team must be willing to create a project management methodology (and multinational project management value-added chain) that would achieve the following goals:

- Combine best practices from all existing project management methodologies and project management value-added chains.

- Create a methodology that encompasses the entire project management value-added chain from suppliers to customers.

- Meet any industry standards, such as those established by the Project Management Institute (PMI) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO).

- Share best practices among all company organizations.

- Achieve the corporate launch goals of timing, cost, quality, and efficiency.

- Optimize procedures, deliverables, roles, and responsibilities periodically.

-

Provide clear and useful documentation.

At one company, the following benefits were found:

- Common terminology across the entire organization

- Unification of all divisions within the company

- Common forms and reports

- Guidelines for less experienced project managers and team members

- Clearer definition of roles and responsibilities

- Reduction in the number of procedures and forms

- No duplication in reporting

The following recommendations can be made:

- Use a common written system for managing programs. If new companies are acquired, bring them into the basic system as quickly as is reasonable.

- Respect all parties. You cannot force one company to accept another company’s systems. There has to be selling, consensus, and modifications.

- It takes time to allow different corporate cultures to come together. Pushing too hard will simply alienate people. Steady emphasis and pushing by management are ultimately the best way to achieve integration of systems and cultures.

- Sharing management personnel among the merging companies helps to bring the systems and people together quickly.

- There must be a common “process owner” for the project management system. A person on the vice-presidential level would be appropriate.

17.6 INTEGRATION RESULTS

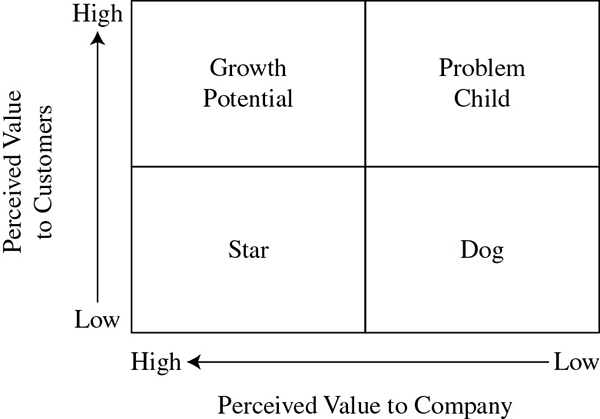

The best-prepared plans do not necessarily guarantee success. Reevaluation is always necessary. Evaluating the integrated project management value added after acquisition and integration is completed can be done using the modified Boston Consulting Group Model, shown in Figure 17-4. The two critical parameters are the perceived value to the company and the perceived value to customers.

Figure 17-4. Project management system after acquisition.

If the final chain has a low perceived value to both the company and the customers, it can be regarded as a “dog.”

Characteristics of a Dog

- There is a lack of internal cooperation, possibly throughout the entire value-added chain.

- The value chain does not interface well with the customers.

- The customer has no faith in the company’s ability to provide the required deliverables.

- The value-added chain processes are overburdened with excessive conflicts.

- Preacquisition expectations were not achieved, and the business may be shrinking.

Possible Strategies to Use with a Dog

- Downsize, descope, or abandon the project management value-added chain.

- Restructure the company to either a projectized or a departmentalized project management organization.

- Allow the business to shrink and focus on selected projects and clients.

- Accept the position of a market follower rather than a market leader.

The problem child quadrant in Figure 17-4 represents a value-added chain that has a high perceived value to the company but is held in low esteem by customers.

Characteristics of a Problem Child

- The customer has some faith in the company’s ability to deliver but no faith in the project management value-added chain.

- Incompatible systems may exist within the value-added chain.

- Employees are still skeptical about the capability of the integrated project management value-added chain.

- Projects are completed more on a trial-by-fire basis rather than on a structured approach.

- Fragmented pockets of project management may still exist in both the landlord and the tenant.

Possible Strategies for a Problem Child Value Chain

- Invest heavily in training and education to obtain a cooperative culture.

- Carefully monitor cross-functional interfacing across the entire chain.

- Seek out visible project management allies in both the landlord and the tenant.

- Use of small breakthrough projects may be appropriate.

The growth-potential quadrant in Figure 17-4 has the potential to achieve preacquisition decision-making expectations. This value-added chain is perceived highly by both the company and its clients.

Characteristics of a Growth-Potential Value-Added Chain

- Limited, successful projects are using the chain.

- The culture within the chain is based on trust.

- Visible and effective sponsorship exists.

- Both the landlord and the tenant regard project management as a profession.

Possible Strategies for a Growth-Potential Project Management Value-Added Chain

- Maintain slow growth leading to larger and more complex projects.

- Invest in methodology enhancements.

- Begin selling complete solutions to customers rather than simply products or services.

- Focus on improved customer relations using the project management value-added chain.

In the final quadrant in Figure 17-4, the value chain is viewed as a star. This has a high perceived value to the company but a low perceived value to the customer. The reason for customers’ low perceived value is that you have already convinced them of the ability of your chain to deliver, and your customers now focus on the deliverables rather than the methodology.

Characteristics of a Star Project Management Value-Added Chain

- A highly cooperative culture exists.

- The triple constraints are satisfied.

- Your customers treat you as a partner rather than as a contractor.

Potential Strategies for a Star Value-Added Chain

- Invest heavily in state-of-the-art supportive subsystems for the chain.

- Integrate your project management information systems (PMIS) into the customer’s information systems.

- Allow for customer input into enhancements for your chain.

17.7 VALUE CHAIN STRATEGIES

At the beginning of this chapter, the focus was on the strategic and financial objectives established during preacquisition decision making. However, to achieve these objectives, the company must understand its competitive advantage and competitive market after acquisition integration. Four generic strategies for a project management value-added chain are shown in Figure 17-5. The company must address two fundamental questions concerning postacquisition integration:

- Will the organization now compete on cost or uniqueness of products and services?

- Will the postacquisition marketplace be broad or narrow?

Figure 17-5. Four generic strategies for project management.

The answer to these two questions often dictates the types of projects that are ideal for the value-added chain project management methodology. This is shown in Figure 17-6. Low-risk projects require noncomplex methodologies, whereas high-risk projects require complex methodologies. The complexity of the methodology can have an impact on the time needed for postacquisition integration. The longest integration time occurs when a company wants a project management value-added chain to provide complete solution project management, which includes product and service development, installation, and follow-up. It can also include platform project management. Emphasis is on customer satisfaction, trust, and follow-on work.

Figure 17-6. Risk spectrum for type of project.

Project management methodologies are often a reflection of a company’s tolerance for risk. As shown in Figure 17-7, companies with a high tolerance for risk develop project management value-added chains capable of handling complex R&D projects and become market leaders. At the other end of the spectrum are enhancement projects that focus on maintaining market share and becoming a follower rather than a market leader.

Figure 17-7. Risk spectrum for the types of R&D projects.

17.8 FAILURE AND RESTRUCTURING

Great expectations often lead to great failures. When integrated project management value-added chains fail, the company has three viable but undesirable alternatives:

- Downsize the company.

- Downsize the number of projects and compress the value-added chain.

- Focus on a selected customer business base.

The short- and long-term outcomes for these alternatives are shown in Figure 17-8.

Figure 17-8. Restructuring outcomes.

Failure often occurs because the preacquisition decision-making phase was based on illusions rather than fact. Typical illusions include:

- Integrating project management methodologies will automatically reduce or eliminate duplicated steps in the value-added chain.

- Expertise in one part of the project management value-added chain could be directly applicable to upstream or downstream activities in the chain.

- A landlord with a strong methodology in part of its value-added chain could effectively force a change on a tenant with a weaker methodology.

- The synergy of combined operations can be achieved overnight.

- Postacquisition integration is a guarantee that technology and intellectual property will be transferred.

- Postacquisition integration is a guarantee that all project managers will be equal in authority and decision making.

Mergers and acquisitions will continue to take place regardless of whether the economy is weak or strong. Hopefully, companies will now pay more attention to postacquisition integration and recognize the potential benefits.