6

Culture

6.0 INTRODUCTION

Perhaps the most significant characteristic of companies that are excellent in project management is their culture. Successful implementation of project management creates an organization and cultures that can change rapidly because of the demands of each project and yet adapt quickly to a constantly changing dynamic environment, perhaps at the same time. Successful companies have to cope with change in real time and live with the potential disorder that comes with it. The situation can become more difficult if two companies with possibly diverse cultures must work together on a common project.

Change is inevitable in all organizations but perhaps more so in project-driven organizations. As such, excellent companies have come to the realization that competitive success can be achieved only if the organization has achieved a culture that promotes and sustains the necessary organizational behavior. Corporate cultures cannot be changed overnight. The time frame is normally years but can be reduced if executive support exists. Also, if as few as one executive refuses to support a potentially good project management culture, disaster can result.

In the early days of project management, a small aerospace company had to develop a project management culture in order to survive. The change was rapid. Unfortunately, the vice president for engineering refused to buy into the new culture. Prior to the acceptance of project management, the power base in the organization had been engineering. All decisions were either instigated or approved by engineering. How could the organization get the vice president to buy into the new culture?

The president realized the problem but was stymied for a practical solution. Getting rid of the vice president was one alternative, but not practical because of his previous successes and technical know-how. The corporation was awarded a two-year project that was strategically important to it. The vice president was then temporarily assigned as the project manager and removed from his position as vice president for engineering. At the completion of the project, the vice president was assigned to fill the newly created position of vice president of project management.

6.1 CREATION OF A CORPORATE CULTURE

Corporate cultures may take a long time to create and put into place but can be torn down overnight. Corporate cultures for project management are based on organizational behavior, not processes. Corporate cultures reflect the goals, beliefs, and aspirations of senior management. It may take years for the building blocks to be in place for a good culture to exist, but that culture can be torn down quickly through the personal whims of one executive who refuses to support project management.

Project management cultures can exist within any organizational structure. The speed at which the culture matures, however, may be based on the size of the company, the size and nature of the projects, and the type of customer, whether it is internal or external. Project management is a culture, not policies and procedures. As a result, it may not be possible to benchmark a project management culture. What works well in one company may not work equally well in another.

Good corporate cultures can also foster better relations with the customer, especially external clients. As an example, one company developed a culture of always being honest in reporting the results of testing accomplished for external customers. Customers, in turn, began treating the contractor as a partner and routinely shared proprietary information so that customers and the contractor could help each other.

Within the excellent companies, the process of project management evolves into a behavioral culture based on multiple-boss reporting. The significance of multiple-boss reporting cannot be overstated. There is a mistaken belief that project management can be benchmarked from one company to another. Benchmarking is the process of continuously comparing and measuring against an organization anywhere in the world in order to gain information that will help your organization improve its performance and competitive position. Competitive benchmarking is where organizational performance is benchmarked against the performance of competing organizations. Process benchmarking is the benchmarking of discrete processes against organizations with performance leadership in these processes.

Since a project management culture is a behavioral culture, benchmarking works best if we benchmark best practices, which are leadership, management, or operational methods that lead to superior performance. Because of the strong behavioral influence, it is almost impossible to transpose a project management culture from one company to another. As mentioned earlier, what works well in one company may not be appropriate or cost-effective in another company.

Strong cultures can form when project management is viewed as a profession and supported by senior management. A strong culture can also be viewed as a primary business differentiator. Strong cultures can focus on either a formal or an informal project management approach. However, with the formation of any culture, there are always some barriers that must be overcome.

According to a spokesperson from AT&T:

Project management is supported from the perspective that the PM [project manager] is seen as a professional with specific job skills and responsibilities to perform as part of the project team. Does the PM get to pick and choose the team and have complete control over budget allocation? No. This is not practical in a large company with many projects competing for funding and subject matter experts in various functional organizations.

A formal project charter naming an individual as a PM is not always done; however, being designated with the role of project manager confers the power that comes with that role. In our movement from informal to more formal, it usually started with project planning and time management, and scope management came in a little bit later.

In recent memory PM has been supported, but there were barriers. The biggest barrier has been in convincing management that they do not have to continue managing all the projects. They can manage the project managers and let the PMs manage the projects. One thing that helps this is to move the PMs so that they are in the same work group, rather than scattered throughout the teams across the company, and have them be supervised by a strong proponent of PM. Another thing that has helped has been the PMCOE’s [project management center of excellence] execution of their mission to improve PM capabilities throughout the company, including impacting the corporate culture supporting PM.

Our success is attributable to a leadership view that led to creating a dedicated project management organization and culture that acknowledges the value of project management to the business. Our vision: Establish a global best-in-class project management discipline designed to maximize the customer experience and increase profitability for AT&T.

In good cultures, the role and responsibilities of the project manager is clearly identified. It is also supported by executive management and understood by everyone in the company. According to Enrique Sevilla Molina, formerly Corporate Project Management Office (PMO) director at Indra:

Based on the historical background of our company and the practices we set in place to manage our projects, we found out that the project manager role constitutes a key factor for project success. Our project management theory and practice has been built to provide full support to the project manager when making decisions and, consequently, to give him or her full responsibility for project definition and execution.

We believe that he or she is not just the one that runs the project or the one that handles the budget or the schedule but the one that “understands and looks at their projects as if they were running their own business,” as our CEO used to say, with an integrated approach to his/her job.

Our culture sets the priority on supporting the project managers in their job, helping them in the decision-making processes, and providing them with the needed tools and training to do their job. This approach allow for a certain degree of a not-so-strict formal processes. This allows the project manager’s responsibility and initiative to be displayed, but always under compliance with the framework and set of rules that allows for a solid accounting and results reporting.

We can say that project management has always been supported throughout the different stages of evolution of the company, and throughout the different business units, although some areas have been more reluctant in implementing changes in their established way of performing the job. One of the main barriers or drawbacks is the ability to use the same project management concepts for the different types of projects and products. It is still a major concern in our training programs to try to explain how the framework and the methodology is applied to projects with a high degree of definition in scope and to projects with a lesser degree of definition (fuzzy projects).

6.2 CORPORATE VALUES

An important part of the culture in excellent companies is an established set of values that all employees abide by. The values go beyond the normal “standard practice” manuals and morality and ethics in dealing with customers. Ensuring that company values and project management are congruent is vital to the success of any project. In order to ensure this congruence of values, it is important that company goals, objectives, and values be well understood by all members of the project team.

Many forms of value make up successful cultures. Figure 6-1 shows some of the types of values. Every company can have its own unique set of values that works well for it. Groups of values may not be interchangeable from company to company.

Figure 6-1. Types of values.

One of the more interesting characteristics of successful cultures is that productivity and cooperation tend to increase when employees socialize outside of work as well as at work.

Successful project management can flourish within any structure, no matter how terrible the structure looks on paper, but the culture within the organization must support the four basic values of project management:

- Cooperation

- Teamwork

- Trust

- Effective communication

Some companies prefer to add in a fifth bullet, namely ethical conduct. This is largely due to PMI’s Code of Conduct and Professional Responsibility.

6.3 TYPES OF CULTURES

There are different types of project management cultures, which vary according to the nature of the business, the amount of trust and cooperation, and the competitive environment. Typical types of cultures include:

- Cooperative cultures. These are based on trust and effective communication, not only internally but externally as well with stakeholders and clients.

- Noncooperative cultures. In these cultures, mistrust prevails. Employees worry more about themselves and their personal interests than what is best for the team, company, or customer.

- Competitive cultures. These cultures force project teams to compete with one another for valuable corporate resources. In these cultures, project managers often demand that employees demonstrate more loyalty to the project than to their line manager. This can be disastrous when employees are working on multiple projects at the same time and receive different instructions from the project and the functional manager.

- Isolated cultures. These occur when a large organization allows functional units to develop their own project management cultures. This could also result in a culture-within-a-culture environment within strategic business units. It can be disastrous when multiple isolated cultures must interface with one another.

- Fragmented cultures. Projects where part of the team is geographically separated from the rest of the team may lead to a fragmented culture. Virtual teams are often considered fragmented cultures. Fragmented cultures also occur on multinational projects, where the home office or corporate team may have a strong culture for project management, but the foreign team has no sustainable project management culture.

Cooperative cultures thrive on effective communications, trust, and cooperation. Decisions are made based on the best interest of all of the stakeholders. Executive sponsorship, whether individual or committee, is more passive than active, and very few problems ever go up to the executive levels for resolution. Projects are managed more informally than formally, with minimum documentation, and often meetings are held only as needed. This type of project management culture takes years to achieve and functions well during both favorable and unfavorable economic conditions.

Noncooperative cultures are reflections of senior management’s inability to cooperate among themselves and possibly their inability to cooperate with the workforce. Respect is nonexistent. Noncooperative cultures can produce a good deliverable for the customer if the end justifies the means. However, this culture does not generate the number of project successes achievable with the cooperative culture.

Competitive cultures can be healthy in the short term, especially if an abundance of work exists. Long-term effects are usually not favorable. An electronics firm continuously bid on projects that required the cooperation of three departments. Management then implemented the unhealthy decision of allowing each of the three departments to bid on every job, thus creating internal competition as they bid against each other. One department would be awarded the contract, and the other two departments would be treated as subcontractors.

Management believed that this competitiveness was healthy. Unfortunately, the long-term results were disastrous. The three departments refused to talk to one another, and the sharing of information stopped. In order to get the job done for the price quoted, the departments began outsourcing small amounts of work rather than using the other departments, which were more expensive. As more and more work was being outsourced, layoffs occurred. Management then realized the disadvantages of a competitive culture.

The type of culture can be impacted by the industry and the size and nature of the business. According to Eric Alan Johnson and Jeffrey Alan Neal:

Data-orientated culture: The data-orientated culture (also known as the data-driven culture and knowledge-based management) is characterized by leadership and project managers basing critical business actions on the results of quantitative methods. These methods include various tools and techniques such as descriptive and inferential statistics, hypothesis testing, and modeling. This type of management culture is critically dependent on a consistent and accurate data collection system specifically designed to provide key performance measurements (metrics). A robust measurement system analysis program is needed to ensure the accuracy and ultimate usability of the data.

This type of culture also employs visual management techniques to display key business and program objects to the entire work population. The intent of a visual management program is not only to display the progress and performance of the project, but to instill a sense of pride and ownership in the results with those who are ultimately responsible for project and program success … the employees themselves.

Also critical to the success of this type of management culture is the training required to implement the more technical aspects of such a system. In order to accurately collect, assess, and enable accurate decision making the diverse types of data (both nominal and interval data), the organization needs specialists skilled in various data analysis and interpretation techniques.1

6.4 CORPORATE CULTURES AT WORK

Cooperative cultures are based on trust, communication, cooperation, and teamwork. As a result, the structure of the organization may become unimportant. Restructuring a company simply to bring in project management may lead to disaster. Companies should be restructured for other reasons, such as getting closer to the customer.

Successful project management can occur within any structure, no matter how bad the structure appears on paper, if the culture within the organization promotes teamwork, cooperation, trust, and effective communications.

Boeing

In the early years of project management, aerospace and defense contractors set up customer-focused project offices for specific customers, such as the Air Force, Army, and Navy. One of the benefits of these project offices was the ability to create a specific working relationship and culture for that customer.

Developing a specific relationship or culture was justified because the projects often lasted for decades. It was like having a culture within a culture. When the projects disappeared and the project office was no longer needed, the culture within that project office might very well disappear as well.

Sometimes one large project can require a permanent culture change within a company. Such was the case at Boeing with the decision to design and build the Boeing 777 airplane.2 The Boeing 777 project would require new technology and a radical change in the way people would be required to work together. The culture change would permeate all levels of management, from the highest levels down to the workers on the shop floor. Table 6-1 shows some of the changes that took place.2 The intent of the table is to show that on large, long-term projects, cultural change may be necessary.

TABLE 6-1 CHANGES DUE TO BOEING 777 NEW AIRPLANE PROJECT

| Situation | Previous New Airplane Projects | Boeing 777 |

| Executive communications | Secretive | Open |

| Communication flow | Vertical | Horizontal |

| Thinking process | Two dimensional | Three dimensional |

| Decision making | Centralized | Decentralized |

| Empowerment | Managers | Down to factory workers |

| Project managers | Managers | Down to nonmanagers |

| Problem solving | Individual | Team |

| Performance reviews (of managers) | One way | Three ways |

| Human resources problem focus | Weak | Strong |

| Meetings style | Secretive | Open |

| Customer involvement | Very low | Very high |

| Core values | End result/quality | Leadership/participation/customer satisfaction |

| Speed of decisions | Slow | Fast |

| Life-cycle costing | Minimal | Extensive |

| Design flexibility | Minimal | Extensive |

Note: The information presented in this table is the author’s interpretation of some of the changes that occurred, not necessarily Boeing’s official opinion.

As project management matures and the project manager is given more and more responsibility, those managers may be given the responsibility for wage and salary administration. However, even excellent companies are still struggling with this new approach. The first problem is that project managers may not be on the management pay scale in the company but are being given the right to sign performance evaluations.

The second problem is determining what method of evaluation should be used for union employees. This is probably the most serious problem, and the jury is not yet in on what will and will not work. One reason why executives are a little reluctant to implement wage and salary administration that affects project management is because of union involvement, which dramatically changes the picture, especially if a person on a project team decides that a union worker is considered promotable when in fact his or her line manager says that promotion must be based on a union criterion.” There is no black-and-white answer for the issue, and most companies have not even addressed the problem yet.

Midwest Corporation (Disguised Company)

The larger the company, the more difficult it is to establish a uniform project management culture across the entire company. Large companies have pockets of project management, each of which can mature at a different rate. A large Midwest corporation had one division that was outstanding in project management. The culture was strong, and everyone supported project management. This division won awards and recognition on its ability to manage projects successfully. Yet at the same time, a sister division was approximately five years behind the excellent division in project management maturity. During an audit of the sister division, the following problem areas were identified:

- Continuous process changes due to new technology

- Not enough time allocated for effort

- Too much outside interference (meetings, delays, etc.)

- Schedules laid out based on assumptions that eventually change during execution of the project

- Imbalance of workforce

- Differing objectives among groups

- Use of a process that allows for no flexibility to “freelance”

- Inability to openly discuss issues without some people taking technical criticism as personal criticism

- Lack of quality planning, scheduling, and progress tracking

- No resource tracking

- Inheriting someone else’s project and finding little or no supporting documentation

- Dealing with contract or agency management

- Changing or expanding project expectations

- Constantly changing deadlines

- Last-minute requirements changes

- People on projects having hidden agendas

- Project scope unclear right from the beginning

- Dependence on resources without having control over them

- Finger pointing: “It’s not my problem”

- No formal cost-estimating process

- Lack of understanding of a work breakdown structure

- Little or no customer focus

- Duplication of efforts

- Poor or lack of “voice of the customer” input on needs/wants

- Limited abilities of support people

- Lack of management direction

- No product/project champion

- Poorly run meetings

- People not cooperating easily

- People taking offense at being asked to do the job they are expected to do, while their managers seek only to develop a high-quality product

- Some tasks lacking a known duration

- People who want to be involved but do not have the skills needed to solve the problem

- Dependencies: making sure that when specifications change, other things that depend on them also change

- Dealing with daily fires without jeopardizing the scheduled work

- Overlapping assignments (three releases at once)

- Not having the right personnel assigned to the teams

- Disappearance of management support

- Work being started in days-from-due-date mode rather than in as-soon-as- possible mode

- Turf protection by nonmanagement employees

- Nonexistent risk management

- Project scope creep (incremental changes that are viewed as small at the time but that add up to large increments)

- Ineffective communications with overseas activities

- Vague/changing responsibilities (who is driving the bus?)

Large companies tend to favor pockets of project management rather than a company-wide culture. However, there are situations in which a company must develop a company-wide culture to remain competitive. Sometimes it is simply to remain a major competitor; other times it is to become a global company.

6.5 GEA AND HEINEKEN COLLABORATION: A LEARNING EXPERIENCE

One of the most important aspects of the project management discipline is to adapt to the specific characteristics of the project, to the work culture of the country where the project is developed as well as to the customer that owns the project.

GEA, a world-class technology supplier of turnkey plants in a wide range of process industries, and particularly one of the largest suppliers for the food and beverage industry, and Heineken, the world’s third largest brewing company, have been working together worldwide in close partnership to execute different types of projects at the Heineken plants according to Heineken needs. The last projects executed for the Heineken plants in Spain and, especially, the close collaboration between the Heineken and GEA local teams in Spain are great examples to identify from the cultural perspective the best practices learned and applied in project management to meet the strategic objectives of both companies.

Cultural aspects have been key in the projects developed by GEA for Heineken in several plants of Spain. To be able to do it successfully, both teams had to work on an open-minded approach to combine the different project management methodologies between both companies.

Project management is a core competency of GEA. To enable all project managers to deliver projects consistently on time, within budget, and according to customers’ expectations, GEA has developed project management methods, tools, and training. This is all covered on the GEA Project Management Manual.

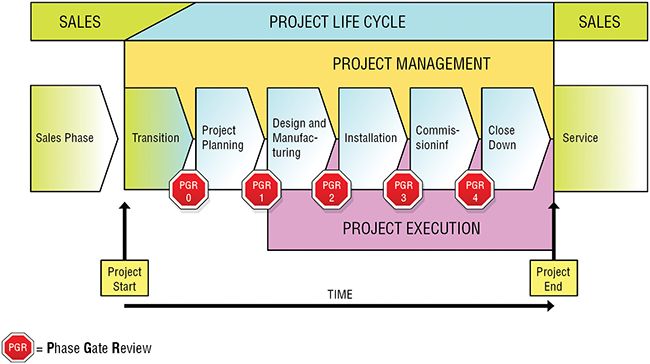

This manual, based on the PMBOK® Guide,* explains to the project managers how to manage and execute the projects. It divides the project in single steps, which can be considered small projects on their own. The methodology secures not only secures the correct project execution but also a smooth transition between the project and the sales and after-sales stages. (See Figure 6-2.)

Figure 6-2. GEA Project Management Model.

This model is key the projects executed by GEA and provides great value added on the collaboration between GEA and Heineken in Spain.

We explain the sequence of steps shown in the model next.

Transition Stage

- The interaction between Heineken project teams and project managers is intense during the sales phase to ensure the needs of the customer are included in the submitted quotation.

- Clarifying the scope of the project and all the terms and conditions was a must for creating solid bases for the development of the project. Even issues that were relevant for the project future stages, such as occupational health and safety, plant infrastructure, were discussed with Heineken at this point.

- Frequent alignment meetings were held, and they created an excellent relationship between project managers and project team members of both parties. Of course, whenever possible, these meetings are held with a predetermined agenda and at specific intervals. From the GEA perspective, the exercise allowed a better understanding not only of project requirements but also of the customer’s most important stakeholders.

Planning Stage

- During the planning stage, the contact between both project managers was very deep. From the contractual dates, all processes for creating the different management plans were done jointly, with a deep focus on communication, risk assessment, resources allocation, schedule (of activities, procurement, logistics, etc.), quality expected, and so on.

- Passionate discussions were held until a common ground was reached that was, in the end, very beneficial for project execution and for the relationship among project team members. For both companies and their top management, from that point on, only one joint project team existed.

- Although it belongs to other stages of the project, updates of the timing schedule based on project evolution were very useful for both parties and a way of facing the issues and risks of the project successfully.

Design and Engineering

- Design and engineering was also done jointly. GEA, working with the set of requirements for the project established by Heineken, developed the detailed engineering in all its aspects (process and instrumentation diagrams, three-dimensional solids, layouts, skids, hydraulic design, equipment and component selection, etc.).

- Rounds of preliminary consultations, work development, and further validation were carried on one after another and in all disciplines (mechanical and process, electrical).

- As a consequence, the relatively large amount of time consumed by these preliminary consultations was later recovered by reducing the scope variations to minor changes in the manufacturing of equipment, erection of the installation, and its commissioning. The open minds on both sides was a factor that allowed good engineering development.

- Heineken showed its commitment to GEA by being open to sharing key factors of the process with GEA to design and engineer. Transparency, mutual trust, and clear set of goals—of course, all protected by the confidentiality agreement signed by both parties—are very important to securing the success of this part of the project.

- Contrary to the previous stages, where the number of deliverables was not so high, there are a significant number of deliverables in the design and engineering stage. Along with the update of the already existing documents (mainly timing schedule and risk assessment), these included process and instrumentation diagrams; electrical and entity drawings; three-dimensional designs; layouts; and hydraulic, electrical, and structural calculations.

- Also, it is important to remark that this stage was also relevant to the procurement of components and manufacturing of the equipment. GEA consulted Heineken about the technical specifications for the equipment and about the use of certified suppliers and contractors. Procurement dates were also agreed in order to secure Heineken’s readiness to store safely and securely all the material needed for the further erection of the installation in its plant.

- As an important part of the procurement, GEA provided Heineken with the recommended spare parts list that will be used later on to support the commissioning of the project. This practice ensures that project commissioning is not affected by missing replacement parts.

Installation Stage

- During the installation stage, the design becomes something real.

- In this stage, the number of stakeholders on the customer side usually expands significantly. In earlier stages, GEA had contact just with the project manager or key engineers; in this stage, many other roles suddenly appear. There is a long list of people to deal with, including relevant people from other contractors (civil works, utilities, occupational health and safety, etc.), other people from the customer (plant management, maintenance, warehousing, etc.) to even government officials (for permits, regulations, formal authorizations, etc.).

- The case of the projects with Heineken has been a good example of what are effective project management practices. The solid relationship developed during previous stages was very important for a smooth completion of the installation, when clashes between integrators and the customer often occur. Heineken and GEA worked without issues. The equipment and components were according with the approved process and instrumentation diagrams, and their quality and standards were correct. Infrastructures for mobilization, warehouse space, services, and the like were already available for the start of operations in the plant.

- Also, in this stage the interaction with other contractors is very intense. Daily joint meetings for aligning the work to be done are key not only for better coordination but also for avoiding incidents and accidents. With regard to the interactions the work done by Heineken has to be praised.

- Another relevant subject for the development of the project is the control of the subcontractors involved in the mechanical and electrical installation. The interaction among GEA, its subcontractors, and Heineken was intense and always managed from a proactive perspective, obtaining good results for the project development.

- Once that the installation is close to its completion, a common verification round should be done to ensure that all issues are properly registered and actions for their resolution are specified.

Commissioning Stage

- It is important to start the commissioning stage, with the installation completely finished and verified. If that is not possible, a good list of pending points, including owners and dates of resolution, is vital.

- In this stage, more than ever during the project, interactions between the different integrators and the customer are frequent and sometimes conflict-laden. The GEA approach is to have the customer—not only its management but also those in all operational levels—involved as much as possible. Heineken management was very receptive and cooperative in all the projects developed in its Spanish plants. The usual conflicts due to a project’s interference with a plant’s regular production runs were minimized, thanks to the previous alignment with management of the production departments. Also, services and utilities for the areas subjected to the project works were provided in a timely manner, easing the start of the commissioning.

- System acceptance tests were performed successfully by Heineken and ensured that the production was reliable, robust, and repeatable. Also, during the installation phase, a list of pending issues was created for recording, analyzing, and fixing all the issues that needed attention to leave the plant in good condition, although these issues did not impede regular production.

- Project documentation was provided at the end of the commissioning. It covered all maintenance requirements as well as the material list to be used for plant engineers and technicians. Plant operators are trained during this stage. Here the intervention of Heineken in providing suitable people as well as the proper facilities was key for securing the proper environment for doing a good training. The main goal is to have the people ready for maintaining and operating the plant once a project is handed over to the customer.

- The start of the product trials and particularly the commercial production release and the provisional acceptance of the installation, allowed the handover of the asset to Heineken and the start of the warranty period. As mentioned in the design and engineering stage, the existence of spare lists mitigated the impact of component and equipment breakdowns.

- From that point on, all the warranty issues would be managed by GEA Service and Heineken Production and Maintenance departments. In that regard, it is very important to secure a smooth transition from the project stage to the after-sales phase, and the project managers of both teams work together to support any issues that need to be resolved.

Close-Down Stage

- The close-down stage provides a fine-tuning of the installation and ensures a good ramp-up until the plant reaches full capacity. If there are issues pending from the commissioning, they are also fixed; the project’s punch list is completely cleared. The final accomplishment of the project key performance indicators is a must and it is verified once again, but now at full production. Now the transition of the operations, in GEA from project execution to service and in Heineken from engineering to production, is complete and final, opening the after-sales stage, which, although outside of the project life cycle, should be transitioned carefully too.

- This stage is also the one for closing the project administratively. From GEA side updated the project repository with all the data about the plant, and Heineken provided the final acceptance of the project and release of final payments according to the financial milestones.

- It is also the time for preparing the internal session of lessons learned and the project evaluation, internally and by the customer. Both lessons learned and project evaluation allow the listing of good practices that should be lauded and bad ones that should be rectified in future projects. They are an important part of the continuous improvement philosophy praised by GEA and the basis of the first and most important of its values, excellence.

To summarize, the framework for the collaboration between Heineken and GEA for the projects developed jointly according to this methodology and the support of the management, not only during the project execution but also in the sales, after-sales, and service stages, were crucial for project success and for the creation of a strong partnership between GEA and Heineken.

Along with that, the teams from both companies learned, project after project, how to improve their collaboration and how to work together in future projects. The success of this partnership was not only the good foundation from the beginning but also the joint aim of improving and learning from the obstacles found along the way that we overcame together.

Finally, along with following a project management methodology and being close to the customer, the other most important best practices shared between Heineken and GEA were:

- Stakeholder management. The Heineken project manager involved all departments that could be impacted on every meeting. That was key for the stakeholder’s engagement. Even if their needs were considered on every meeting, when they were participating, their involvement and buy in of them was much higher.

- Scope management.

- Collecting requirements Managing assumptions and validating the acceptance criteria are very relevant. Technical meetings to review the project scope provided open discussions and valuable insights that allowed project teams to make significant improvements on engineering. On the initial projects, some items were assumed, which created some discrepancies on the next project phase. The meetings became more important project after project and reduced the risks of issues during assembly and commissioning.

- Scope validation. During the projects, GEA understood which engineering tasks were really important for Heineken and provided an added value for them. The engineering reviews and especially the three-dimensional reviews were critical for Heineken, and those were settled as an important milestone on the project schedule.

- Scope lessons learned. Different engineering design criteria were used on the initial projects. As a result, during the commissioning, they were controlled in a different way than Heineken expected. For the next projects, before defining the design criteria, all parties verified that they met Heineken expectations, even if the original design criteria were initially valid.

- Resource management. The expectations of resource management on site during the execution phase were different between Heineken and GEA in terms of the number of resources, accountability, and others. Due to the lack of task management between the teams, some phases exceeded while others fell behind initial expectations. Expectations were aligned and improved in the next project, creating more open communication to review such matters.

- Communication management. Even if regular and frequent communications were defined between the teams to cover needs, the success factor for managing project priorities was the close communication between the GEA and Heineken project managers.

Without a doubt, taking care of all these best practices is the best way to ensure a good project execution and to secure the sustainability of GEA and its customers.

6.6 INDRA: BUILDING A COHESIVE CULTURE4

At Indra, the project manager role constitutes a key factor for project success. This is because running projects is a core part of our business. As such, company policies and practices are oriented to provide full support to project managers and to give them full responsibility on the project definition and execution. In the words of our former chief executive (CEO): “Project managers must look at their projects as if they were running their own business.”

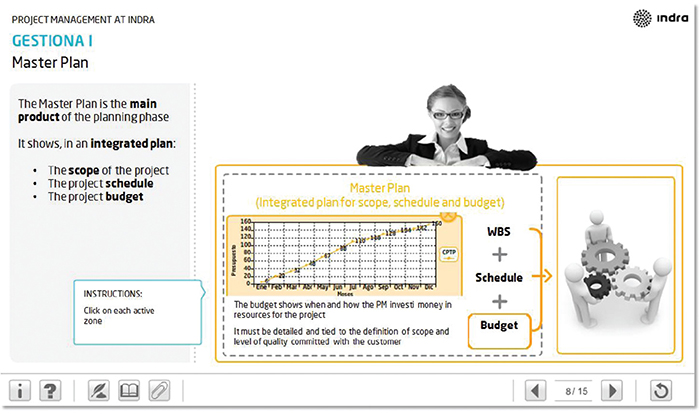

This sentence distills the basis of the project management culture at Indra. It implies that a project manager must have an integrated approach to their job, not only focusing on main objectives tied to the triple constraints, taking care of schedule and cost baselines, but also having a business perspective and pushing to deliver results that will fulfill their business unit objectives (profitability, cost efficiency, development of resources, productivity, etc.) The project management foundations are shown in Figure 6-3.

Figure 6-3. Project management foundations.

As of 2013, the corporate PMO provided support to around 3,300 project managers with clear directions, missions, strategies, methodologies, and a set of common tools and procedures to develop their jobs. We were responsible for developing and updating the Indra Project Management Methodology (IPMM), the Corporate Project Management Methodology. Based on that development, requirements for upgrading the company PMIS are defined and deployed. Ongoing support is provided both to business units and PM individuals, in terms of training and education, informal networking and participation in different initiatives related to project management that are required by the business units. Our final objective is building and consolidating a strong and recognizable project management culture within Indra, whatever the performing unit, geography, or business sector. In 2005 we started an internal certification program as PMP® credential holders5 for a small group of senior program and project managers and business unit managers. This certification program has been carried out yearly since then and has become one of the most sought-after training initiatives by project managers. Business managers carefully select the candidates that participate in the program.

In total, more than 950 professionals have been through the training process to become PMP® credential holders. We achieved the objective of counting on 500 certified PMP®credential holders by the end of 2012. As of May 2013, we had over 500 PMP® credential holders.

These figures wouldn’t mean nothing without a context. For us achieving these figures mean that an important proportion of the most experienced and talented professionals at Indra are well trained in project management best practices. Taking into account that our project management methodology, IPMM, is aligned with the PMBOK® Guide, then we could intuit that a certified PMP® credential holder could easily spread out the knowledge and experience in project management best practices in her area of influence, be this her program, project or business unit. This is a way that works when it comes to settle a strong project management culture in all branches within the company. (See Figure 6-4.)

Figure 6-4. People: Internal trainers.

We started in 2008 having PMP® credential holders collaborating as internal trainers by delivering content on the course “Project Management at Indra,” created by the Corporate PMO. This course explains IPMM and project management information systems. Thanks to this initiative, we are training our people in the PMBOK® standard. At the same time, the experience of the trainer is used to provide a fitted project management context, using projects and services that Indra provides to its customers as training examples. In fact, this collaboration has been a success, having win-win result for all participants:

- PMP® credential holders contribute to create a better project management culture, spreading best practices within the company and also getting professional development units to maintain their certification.

- Trainees connect directly with the content, without any interpretation that an external trainer could provide, as the teacher is a PMP® credential holder who knows well which issues must be handled when it comes to managing a project in our company.

- Human resources training departments also win, because they can invest money in other areas that could need external trainers.

- Corporate PMOs must supervise and support the consistency of the message being delivered in the training process.

In the end it is Indra as whole that benefits, because this project management course content has been put into e-learning format, has been translated into English and Portuguese, and has been included as a mandatory content in the project management training paths of every Indra company, wherever in the world this might be. (See Figure 6-5.)

Figure 6-5. “Project Management at Indra” course on the e-learning platform.

In addition to this, in 2010 the human resources department made available to all employees one platform accessed from the intranet aimed to let people connect, share, and learn from each other. This platform (named “Sharing Knowledge”) has the look and feel of a social network and aims to support the informal exchange of knowledge and experiences between professionals. Its scope is corporate and local, and it helps to quickly and easily deliver content on best practices and methodologies, management, and technical issues and business information. It also has the possibility of creating groups and communities and even broadcasting digital content and courses.

For us, Sharing Knowledge has been a powerful tool to get our project managers into the loop and in touch with the Corporate PMO and also to keep building project management culture. We created PMPnet (see Figure 6-6) for certified professionals at Indra who want to be in touch, be updated with any interesting initiative or activity, or simply contribute with experiences and ideas.

Figure 6-6. “PMPnet” in Sharing Knowledge tool.

6.7 DFCU FINANCIAL7

At $3.4 billion in assets, DFCU Financial is the largest credit union in Michigan and among the top 40 largest in the nation. With a 318.7 percent increase in net income since 2000, DFCU Financial has never done better, and effective project implementation has played a key role. At the root of this success story is a lesson in how to leverage what is best about your corporate culture. The story is also proof that staying true to core values is a sure way to sustain success over the long haul.

1997 to 2005: Overcoming the Past

Rolling back the clock to late 1997, I had just volunteered to be the Y2K project manager—the potential scope, scale, and risk associated with this project scared most folks away. And with some justification—this was not a company known for its project successes. We made it through very well, however, and it taught me a lot about the DFCU Financial culture. We did not have a fancy methodology. We did not have business unit managers who were used to being formally and actively involved in projects. We did not even have many information technology (IT) resources who were used to being personally responsible for specific deliverables. What we did have, however, was a shared core value to outstanding service—to doing whatever was necessary to get the job done well. It was amazing to me how effective that value was when combined with a well-chosen sampling of formal project management techniques.

Having tasted project management success, we attempted to establish a formal project management methodology—the theory being that if a little formal project management worked well, lots more would be better. In spite of its bureaucratic beauty, this methodology did not ensure a successful core system conversion in mid-2000. We were back to the drawing board concerning project management and were facing a daunting list of required projects.

With the appointment of a new president in late 2000, DFCU Financial’s executive team began to change. It did not take long for the new team to assess the cultural balance sheet. On the debit side, we faced several cultural challenges directly affecting project success:

- Lack of accountability for project execution

- Poor strategic planning and tactical prioritization

- Projects controlled almost exclusively by IT

- Project management overly bureaucratic

- Limited empowerment

On the plus side, our greatest strength was still our strong service culture. Tasked with analyzing the company’s value proposition in the marketplace, Lee Ann Mares, former senior vice president of marketing, made the following observations:

Through the stories that surfaced in focus groups with members and employees, it became very clear that this organization’s legacy was extraordinary service. Confirming that the DFCU brand was all about service was the easy part. Making that generality accessible and actionable was tough. How do you break a high-minded concept like outstanding service into things that people can relate to in their day-to-day jobs? We came up with three crisp, clear guiding principles: “Make Their Day,” “Make It Easy,” and “Be an Expert.” Interestingly enough, these simple rules have not only given us a common language but have helped us to keep moving the bar higher in so many ways. We then worked with line employees from across the organization to elaborate further on the Principles. The result was a list of 13 brand actions—things each of us can do to provide outstanding service. (See Table 6-2.)

TABLE 6-2 DFCU FINANCIAL BRAND ACTIONS

| • Make Their Day—Make It Easy—Be an Expert | |

| Voice | We recognize team members as the key to the company’s success, and each team member’s role, contributions, and voice are valued. |

| Promise | Our brand promise and its guiding principles are the foundation of DFCU Financial’s uncompromising level of service. The promise and principles are the common goals we share and must be known and owned by all of us. |

| Goals | We communicate company objectives and key initiatives to all team members, and it is everyone’s responsibility to know them. |

| Clarity | To create a participative working environment, we each have the right to clearly defined job expectations, training and resources to support job function and a voice in the planning and implementation of our work. |

| Teamwork | We have the responsibility to create a teamwork environment, supporting each other to meet the needs of our members. |

| Protect | We have the responsibility to protect the assets and information of the company and our members. |

| Respect | We are team members serving members, and as professionals, we treat our members and each other with respect. |

| Responsibility | We take responsibility to own issues and complaints until they are resolved or we find an appropriate resource to own them. |

| Empowerment | We are empowered with defined expectations for addressing and resolving member issues. |

| Attitude | We will bring a positive, “can do” attitude to work each day—it is my job! |

| Quality | We will use service quality standards in every interaction with our members or other departments to ensure satisfaction, loyalty, and retention. |

| Image | We take pride in and support our professional image by following dress code guidelines. |

| Pride | We will be ambassadors for DFCU Financial by speaking positively about the company and communicate comments and concerns to the appropriate source. |

While we were busy defining our brand, we were also, of course, executing projects. Since 2000, we had improved our operational efficiency through countless process improvement projects. We replaced several key sub-systems. We launched new products and services and opened new branches. We also got better and better at project execution, due in large part to several specific changes we made in how we handled projects. When we looked closer at what these changes were, it was striking how remarkably congruent they were with our guiding principles and brand actions. As simple as it may sound, we got better at project management by truly living our brand.

Brand Action—Responsibility

Project control was one of the first things changed. Historically, the IT department exclusively controlled most projects. The company’s project managers even reported to the CIO. As former chief financial officer, Eric Schornhorst commented, “Most projects had weak or missing sponsorship on the business side. To better establish project responsibility, we moved the project managers out of IT, and we now assign them to work with a business unit manager for large-scale projects only. The project managers play more of an administrative and facilitating role, with the business unit manager actually providing project leadership.” We updated our leadership curriculum, which all managers must complete, to include a very basic project management course, laying the foundation for further professional development in this area.

Guiding Principle—Make It Easy

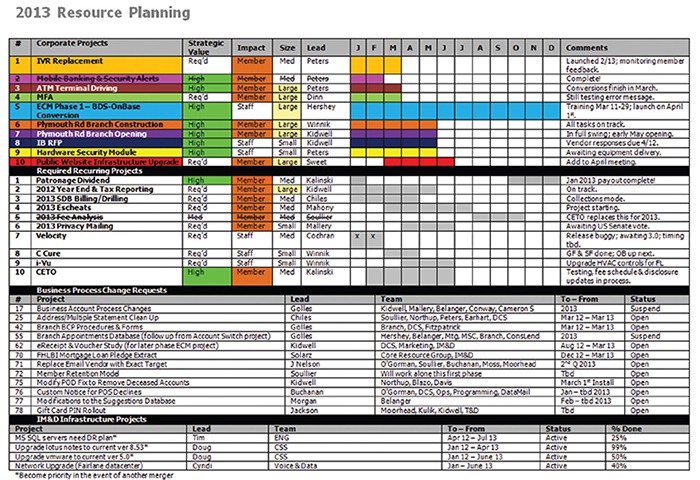

With project ownership more clearly established, we also simplified our project planning and tracking process. We began tracking all large corporate and divisional projects on a single spreadsheet that was reviewed by the executive team monthly. (See Table 6-3 for the report headers.) Project priority was tied directly to our strategic initiatives. Our limited resources were then applied to the most impactful and most critical projects. Eric Schornhorst commented, “Simplifying project management forms and processes has enabled us to focus more on identifying potential roadblocks and issues. We are much better at managing project risk.”

TABLE 6-3 DFCU FINANCIAL CORPORATE PROJECTS LIST REPORT HEADERS

| Column Label | Column Contents |

| Priority | 1 = Board reported and/or top priority 2 = High priority 3 = Corporate priority but can be delayed 4 = Business unit focused or completed as time permits |

| Project | Project Name |

| Description | Brief entry, especially for new initiatives |

| Requirements Document Status | R = Required Y = Received N/A = Not needed |

| Status | Phase (Discovery, Development, Implementation) and percentage completed for current phase |

| Business Owner | Business unit manager who owns the project |

| Project Manager | Person assigned to this role |

| Projected Delivery Time | The year/quarter targeted for delivery |

| Resources | Functional areas or specific staff involved |

| Project Notes | Brief narrative on major upcoming milestones or issues |

Brand Action—Goals

Chief information officer Vince Pittiglio recalled the legacy issue of IT overcommitment.

Without effective strategic and tactical planning, we used to manage more of a project wish list than a true portfolio of key projects. We in IT would put our list of key infrastructure projects together each year. As the year progressed, individual managers would add new projects to our list. Often, many of these projects had little to do with what we were really trying to achieve strategically. We had more projects than we could do effectively, and to be honest, we often prioritized projects based on IT’s convenience, rather than on what was best for the organization and our members.

Focusing on key initiatives made it possible to say no to low-priority projects that were non-value-added or simply not in our members’ best interest. And the new measuring stick for project success was not merely whether the IT portion of the project was completed but rather that the project met its larger objectives and contributed to the company’s success as a whole.

Brand Action—Teamwork

Historically, DFCU Financial was a strong functional organization. Cross-departmental collaboration was rare and occurred only under very specific conditions. This cultural dynamic did not provide an optimal environment for projects. The monthly project review meeting brought together the entire executive team to discuss all current and upcoming projects. The team decided which projects were in the best interest of the organization as a whole. This critical collaboration contributed to building much more effective, cross-functional project teams. We began to develop a good sense of when a specific team or department needed to get involved in a project. We also gained a much better understanding of the concept that we will succeed or fail together and began working together better than ever.

Brand Action—Empowerment

As now-retired chief operating officer Jerry Brandman pointed out:

Our employees have always been positive and pleasant. But our employees were never encouraged to speak their minds, especially to management. This often had a direct negative impact on projects—people foresaw issues, but felt it was not their place to sound the alarm. A lot of the fear related to not wanting to get others “in trouble.” We have been trying to make it comfortable for people to raise issues. If the emperor is naked, we want to hear about it! To make people visualize the obligation they have to speak up, I ask them to imagine they are riding on a train and that they believe they know something that could put the trip in jeopardy. They have an obligation to pull the cord and stop the train. This has not been easy for people, but we are making headway every day.

Brand Action—Quality

At DFCU Financial project implementation in the past followed more of the big bang approach—implement everything all at once to everyone. When the planets aligned, success was possible. More often than not, however, things were not so smooth. Commented Jerry Brandman, “You have to have a process for rolling things out to your public. You also need to test the waters with a small-scale pilot whenever possible. This allows you to tweak and adjust your project in light of real feedback.” Most employees have accounts at DFCU Financial, so we found we had a convenient pilot audience for major projects such as ATM to debit card conversions and the introduction of eStatements to ensure everything functioned correctly prior to launching to the entire membership.

Bottom line, the most significant best practice at DFCU Financial has been to be true to our core cultural value of providing extraordinary service. As we were working on defining this value and finding ways to make it actionable, we were also making changes to the way we approach project management that were very well aligned with our values. Our commitment to living our brand helped us:

- Move project responsibility from IT to the business units

- Simplify project management forms and processes

- Use project review meetings to set priorities and allocate resources more effectively

- Break down organizational barriers and encourage input on projects from individuals across the organization

- Improve project success through pilots and feedback

As president and CEO, Mark Shobe summarized back in 2005:

Good things happen when you have integrity, when you do what you say you are going to do. The improvements we have made in handling projects have rather naturally come out of our collective commitment to really live up to our brand promise. Have we made a lot of progress in how we manage projects? Yes. Is everything where we want it to be? Not yet. Are we moving in the right direction? You bet. And we have a real good roadmap to get there.

2005 to 2009: Poised for Growth

So, how good was that roadmap? The preceding material was written in early 2005. By objective measures, fiscal years 2005 through 2008 were good ones for DFCU Financial. (See Table 6-4.) With over $2 billion in assets in late 2008, the credit union was ranking in the top 10 among its peers in the most important key measures.

TABLE 6-4 DFCU FINANCIAL RESULTS FOR QUARTER ENDING SEPTEMBER 30, 2008

| Result | Ranking | ||||

| Metric | DFCU | National Peer1 Average |

Regional Peer2 Average |

National Peers |

Regional Peers |

| Return on Assets | 1.94% | 0.42% | 0.77% | 1 | 1 |

| Return on Equity | 13.98% | 4.23% | 7.19% | 2 | 2 |

| Efficiency Ratio | 49.57% | 65.41% | 69.31% | 5 | 3 |

| Capital/Assets | 13.91% | 9.82% | 10.69% | 2 | 9 |

| Total Assets | $2.0B | $3.4B | $1.0B | 39 | 5 |

1 150 largest credit unions as measured by total assets

2 Credit unions with at least $500 million in total assets in the states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Minnesota

So, from a purely financial perspective, DFCU was doing very well, especially given the global economic climate as 2009 began and the fact that DFCU was largely serving members associated with the auto industry sector that is so much a part of the notoriously troubled Michigan economy.

The solid financials were the result of the current administration’s efforts over an eight-year period to streamline and improve operations, clarify DFCU’s brand and value proposition, and initiate effective project selection and execution processes.

While these efforts were under way, the executive team and board of directors were evaluating a troubling metric—one that could undermine the company’s ability to sustain its recent successes: DFCU’s membership has been nearly flat for many years—a trend affecting nearly all U.S. credit unions. They therefore were focused on the critical, strategic issue of growth. And again DFCU’s brand and guiding principles were helping shape the results.

Brand Actions—Voice and Quality; Guiding Principle—Make Their Day

While DFCU’s executive team and board of directors explored several growth options, work on selection of a new core processing system began in mid-2005. The core system conversion project was viewed as a strategic imperative for growth, regardless of DFCU’s operating structure. The prior system conversion in 2000 suffered from poor execution that left behind lingering data and process issues that needed to be addressed. At the start of the conversion project, which began formally in January 2006, the conversion was targeted for October of that same year. From the outset, however, we ran into difficulties with the system vendor. The vendor was going through one of its largest client expansions ever and was having a hard time satisfying all of the demands of the conversion projects in its pipeline. The impact to us was noticeable—high turnover in key vendor project team members, poor-quality deliverables, and lack of responsiveness to conversion issues. Due to the poor quality of the data cuts, the project conversion date was at serious risk by June.

Due to its scope, the system conversion project was the only corporate project commissioned in 2006, and all attention was on it. It was not an easy task, therefore, to deliver the message that the project was in trouble. “Mark was well aware that we were having difficulties when we sat down to discuss whether we would have a smooth October conversion,” commented chief information officer Vince Pittiglio. “I have had to deliver bad news before to other bosses, but the talk I had with Mark was a lot different than those I had before.” Our stated objective of this conversion was basically to do no harm. We all agreed that we could not put our members or our employees through the same type of conversion we experienced in July 2000. It had to be as close to a nonevent as possible. According to Pittiglio, “I laid out the key issues we were facing and the fact that none of us on the project believed they could be resolved by the October date. If we kept to the original date, we believed we would negatively impact member experience.” But our CEO, Mark Shobe, was very clear—he insisted that this project be a quality experience for both members and employees, as we all had agreed at the outset, and he was willing to go to the board to bump the date and to put other key initiatives on hold to ensure the conversion’s success. The project team agreed on a revised conversion date in early June 2007. According to conversion project manager and senior vice president Martha Peters:

Though the team continued to face difficulties with the vendor, we worked hard and got it done without any major issues. It made a real difference to know that the chiefs and the board took our feedback seriously. In the end, it really was a nonevent for most of our members and employees, exactly as we all wanted it to be. It was a tough decision to postpone the conversion, one that many companies are not willing to make. But it was the right decision to make—we really try to live our brand.

Brand Action—Clarity and Teamwork

By the time the system conversion was completed in June 2007, we had really only engaged one project in the previous two years, albeit a large-scale project of strategic importance—which was consciously delayed by eight months. This project drained our resources, so little else was accomplished in those two years. “Coming out of the system conversion was this huge, pent-up project demand. And everyone thought that the issues facing their division were, of course, the most pressing,” commented former chief financial officer Eric Schornhorst. “We found out very quickly that our handy project tracking list and monthly corporate project meeting were insufficient tools for prioritizing how to deploy our scarce project resources.” A small team was quickly assembled to put together a process for initiating and approving projects more effectively and consistently. A key objective for this team was to minimize bureaucracy while trying to establish some useful structure, including a preliminary review of all new requests by the IT division. The output was a simple flow diagram that made the steps in the request and approval process clear to everyone (see Figure 6-7) and a form that integrated the instructions for each section. As the senior vice president of human resources related at the time:

My group was one of the first to use the new process. It was surprisingly well put together and easy to use. We made the pitch to replace our learning management system with a more robust, outsourced solution. It was one of the projects that made it on the 2008 list. To be honest, we were really at the point in our company’s history where we needed a bit more discipline in this process. In years past, we independently advocated for our projects at budget time with our division heads. If we received budgetary approval, we viewed our project as “on the list.” When it came time to actually execute, however, we often had trouble lining up the resources from all the different areas that needed to be involved, especially those in IT.

Figure 6-7. DFCU Financial’s project initiation process.

The new process contributed not only to clarity regarding corporate projects but to teamwork as well. As Schornhorst had reflected in late 2008:

We reviewed the projects requested for 2009 using the new process. While we haven’t completely addressed the backlog of projects created by the system conversion, we also have another project likely to take over the majority of resources in 2009. This is not good news for areas that have not yet seen their projects addressed. What’s interesting though is how little contention there was as we reviewed the docket for 2009—and we had to put many important things on the back burner. I think that when you have everyone review the facts together in lock step, it’s easier to get to a set of priorities that make sense for the organization and are mutually supported regardless of personal interest. It helps to bring the best out in all of us.

So Where Was the Road Headed?

In early 2009, DFCU Financial was poised for membership growth. After a review of charter options, the board and executive team decided to remain a credit union but to pursue other avenues for growth. To that end, as 2009 began, the board put forth for vote a proposal to DFCU’s membership for a merger with CapCom Credit Union, which had nine branch locations in the lower central and western areas of Michigan. According to former chief operating officer Jerry Brandman:

We considered many different options to address our strategic vision for growth and expansion in membership—from mergers to various internal growth strategies. While we in the credit union industry currently face the same challenges as other financial institutions, we also are an industry known for service. And here at DFCU Financial we not only talk about service—we deliver. Our employees are happy and enthusiastic. They treat our members very well. We have been rated in the top 101 companies to work for in southeastern Michigan for five years in a row, based on feedback from our employees. And we have a member shops program that shows us how our service stacks up to industry benchmarks. We have consistently performed at the highest level of service relative to our peers. Merging with CapCom and shifting to a community charter will provide us the growth we need to ensure a bright future for our members and our employees. It will allow us to spread the DFCU brand to other geographic areas. We believe this proposal will be appealing to our members and will be successful. We believe that people want to be a part of our organization.

And for good reason. Also in early 2009, DFCU Financial paid out a $17 million patronage dividend to its members for the third consecutive year, for a total of more than $50 million being paid out since inception, during one of the worst economic times to hit the Motor City in decades. According to Keri Boyd, senior vice president of marketing at the time, “Since we are committed to remaining a credit union, we have looked at ways we could improve our value proposition to existing members and attract new members. The patronage dividend is the cornerstone of our approach to growing the business as a credit union.” As Mark Shobe summed it up:

The board and I did not want to begin the payout until we were confident that we could sustain it over the years. It took hard work, some tough decisions, excellent project execution and diligence in our day-to-day operations to be in the position to share our success with our membership. The simple truth is that the driving force behind our success is our collective commitment to our brand.

So, with a 2009 schedule of agreed-on projects, a potential merger in the offing, and some very, very satisfied members, how is the DFCU roadmap working? “Quite well, thank you!” replied Mark.

2009 to 2013: Paying Dividends in More Ways Than One

During this most recent period in DFCU Financial’s history, we have made good progress on our strategic goal of growth. We completed the CapCom merger in late 2009, the same year we began due diligence for another merger with MidWest Financial Credit Union, based in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The MidWest merger was completed in early 2011. In January 2012, we opened a new branch we built in Novi, Michigan, and at the time of this writing we are building a new branches in other locations. Table 6-5 summarizes the key growth metrics for the last four years.

TABLE 6-5 DFCU FINANCIAL GROWTH METRICS

| 2000 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| Number of Members | 170,812 | 167,910 | 201,329 | 218,374 | 213,869 | 214,454 |

| Number of Branches | 6 | 12 | 12 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| Number of Employees | 409 | 336 | 434 | 426 | 408 | 413 |

| Assets in Billions | $1.2 | $1.9 | $2.4 | $2.7 | $3.0 | $3.2 |

Just as we set out to do, we have indeed grown the business through merger and new branch projects. But growth is not the only measure of success. If managed poorly, growth can have a deleterious effect on core financials, service and employee morale. So, how have we done?

During this same period of time, we have maintained a strong position financially when compared with our peers. Our financial strength has allowed us to continue to pay out an annual patronage dividend to our membership. In January 2013, we paid out our seventh dividend, totaling $21.8 million, accounting for an accumulated total of $133.4 million since 2006. Member satisfaction has never been higher as measured through our member shops program, and in 2012 we were again in the top ranks on this element when benchmarked against our peers.

Not least importantly, we have continued to receive awards that recognize DFCU Financial as a premier employer—awards that are based solely on employee feedback—such as the 101 Best and Brightest Companies to Work For and the Detroit Free Press “Top Workplace” awards.

We have also been recognized for our growth and geographic expansion over the last few years by being named a Michigan Economic “Bright Spot” by Corp! Magazine. These successes are summarized in Table 6-6.

TABLE 6-6 DFCU FINANCIAL SUCCESS METRICS

| 2000 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| Key Financial Metrics1 | ||||||

| Return on Assets | 1.01% | 1.69% | 1.25% | 1.23% | 1.38% | 1.55% |

| Return on Equity | 13.08% | 12.06% | 9.52% | 9.53% | 11.11% | 12.36% |

| Efficiency Ratio | 77.50% | 50.84% | 52.90% | 54.73% | 57.56% | 52.26% |

| Capital/Assets | 7.66% | 14.00% | 13.12% | 12.94% | 12.70% | 12.49% |

| Special Patronage Dividend | ||||||

| Total Payout in Millions | - | $17.5 | $19.3 | $18.9 | $21.1 | $21.8 |

| Member Satisfaction | ||||||

| Member Shops 0 – 5 scale | - | 4.80 | 4.86 | 4.89 | 4.96 | 4.972 |

| Employee Satisfaction | ||||||

| Best & Brightest—Metro Detroit3 | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Best & Brightest—West MI | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ |

| Best & Brightest—National | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ |

1 Compared to our top 50 national peers, DFCU ranked 8th in ROA, 15th in ROE, 5th in efficiency, and 5th in C/A as of 12/31/12.

2 Versus a peer compare score of 4.82 for 2012. Note: Shops began in 2002 with a baseline of 4.05.

3 DFCU has received the 101 Best & Brightest Companies to Work For—Metro Detroit for eight consecutive years.

Brand Is Still How We Do It

When we grow by building new branches, the DFCU Financial brand extends rather naturally. In new branch projects, all elements of brand are well controlled—from the look and feel of the facility, to the training and on boarding of new employees, even to the project methodology we use. Growth by merger is not as organic. Ensuring that brand is protected through these projects is no small feat. According to president and CEO Mark Shobe, “In seeking potential merger partners, we look for organizations that are not only a good fit strategically, but which also ostensibly share our core values. But no matter how well suited the match appears to be, the biggest challenge in any merger project is culture.”

Brand Action—Goals and Clarity

CapCom was the first merger DFCU Financial completed during this period. It provided us access to two new geographical markets, but most important, it presented us with an opportunity for charter change. Originally a federally chartered credit union, DFCU Financial is now a state-chartered community credit union that has growth access to all counties in Michigan’s lower peninsula. To change the charter required a vote of the membership. The membership charter vote was one of the most important tasks within the scope of the CapCom merger project. According senior vice president for strategic marketing and operations Martha Peters, who was the CapCom merger project manager:

For us to achieve what we set out to with this merger, we not only needed to successfully integrate systems and functional areas, we also needed to make a compelling argument to our existing membership base to change our business structure. In making both things happen, we leveraged our brand. We needed to assure our existing members that we would be the same DFCU they had relied on—only better, while at the same time we had to demonstrate to our new CapCom colleagues how they and the members they historically served would benefit by adopting the DFCU Financial culture. To facilitate our success on this project, we were very careful about how we structured the project and communicated our goals. We established a steering committee, comprised of DFCU and CapCom executives, which was responsible for making all major project decisions and assessing and communicating the member and staff impact of these decisions. This structure helped us to keep a pulse on employee and member feedback and to address project risk very effectively.

All key objectives of this project were met—the charter change, the functional integration, the legal merger, and the system integration—and, more important, the DFCU Financial brand came out a winner.

Brand Actions—Respect and Responsibility; Guiding Principle—Make It Easy

As the CapCom merger was successfully wrapping up, I was assigned as project manager for the MidWest Financial merger. While charter change figured heavily in the CapCom merger, it was also a project where we learned a lot about how to do mergers. Since we conducted a formal lessons learned exercise coming out of the CapCom merger, I was able to reuse the elements that worked and focus on the areas that needed strengthening.

Being a small company, we do not have dedicated project management resources. Front-line and back-office business unit managers and their teams are expected to participate as project team members and often serve as project managers. In our merger projects, all managers are responsible for all functional integration tasks that relate to their business unit. They are essentially the project manager for their functional area. Managers whose operations are tightly coupled with the core computer system have even greater responsibility to ensure that data from the relinquishing system is safely and correctly converted into the surviving system. It is a daunting set of responsibilities.