CHAPTER 4

How to Estimate What an Income Property Is Really Worth

Whether you’re a buyer, a seller, or a mortgage lender, one of the most important questions you need to answer is, “What is this property really worth?” It may be argued that value, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. This argument tends to ring true in regard to single-family homes, where conventional wisdom has always held that a house is worth what someone is willing to pay for it. Income-producing property, however, is different. Value is determined by the numbers. The owner of the Yankees may admire a batter’s graceful swing, but he pays for that player’s batting average.

Let’s begin this discussion with a subject that always warms your heart: income.

Everyone in business or finance has encountered the term “net income” and understands its general meaning (i.e., what is left over after expenses are deducted from revenue). With regard to investment real estate, however, the term “net operating income” (NOI) represents a minor variation on this theme and has a very specific meaning. You might think of NOI as the number of dollars a property returns in a given year if the property is purchased for all cash and if there is no consideration of income taxes or depreciation. By more formal definition, it is a property’s gross operating income less the sum of all operating expenses.

You saw these terms in Chapter 2, but they’re critical to your understanding of virtually everything that follows. Let’s review them briefly:

• Gross operating income. Definitions are like artichokes. You need to peel the layers off one at a time. In this case, start with the gross scheduled income, which is the property’s annual income if all space were in fact rented and all the rent actually collected. Subtract from this amount an allowance for vacancy and credit loss. The result is the gross operating income.

Gross Scheduled Income

less Vacancy & Credit Loss

= Gross Operating Income

• Operating expenses. This is the term that causes the greatest mischief. Many people say, “If I have to pay it, then it’s an operating expense.” That is not always true. To be considered a real estate operating expense, an item must be necessary to maintain a piece of a property and to ensure its ability to continue to produce income. Loan payments, depreciation, and capital expenditures are not considered operating expenses.

For example, utilities, supplies, snow removal, and property management are all operating expenses. Repairs and maintenance are operating expenses, but improvements and additions are not—they are capital expenditures. Property tax is an operating expense, but your personal income tax liability generated by owning the property is not. Your mortgage interest may be a deductible expense, but it is not an operating expense. You may need a mortgage to afford the property, but not to operate it.

Subtract the operating expenses from the gross operating income, and you have the NOI.

less Operating Expenses

= Net Operating Income

Why all the nitpicking? Because NOI is essential to your understanding the market value of a piece of income-producing real estate. That market value is a function of the property’s “income stream,” and NOI is at the core of that income stream. As unfeeling as it may sound, a real estate investment is not a handsome assemblage of bricks, boards, bx cables, and bathroom fixtures. It is an income stream generated by the operation of the property, independent of external factors such as financing and income taxes.

Investors don’t decide to buy properties; they decide to buy the income streams of the properties. This is not such a radical notion. When was the last time you chose a stock based on the aesthetics of the stock certificate? (“Broker, what do you have with a nice mauve filigree border?”) Never. You buy the anticipated economic benefits. The same is true of investors in income-producing real estate.

Those readers who have not yet been lulled to sleep by this discussion will alertly point out that they have in fact observed changes in the value of income property brought about by changes in mortgage interest rates and in tax laws. Doesn’t that observation contradict our assertion about external factors?

If you’re familiar with the concept of capitalization rate (which we’ll discuss again below), you recognize that there are two elements to a property’s value equation: the NOI and the cap rate (universal shorthand for capitalization rate). The NOI represents a return on the purchase price of the property, and the cap rate is the rate of that return. Hence, a property with a $1,000,000 purchase price and a $100,000 NOI has a 10% capitalization rate. However, the investor will purchase that property for $1,000,000 only if he or she judges 10% to be a satisfactory rate of return.

What happens if interest rates go up? In that case, there may be other opportunities competing for the investor’s capital—bonds, for example—and that investor may now be interested in this same piece of real property only if its return is higher, say 12%. Apply the 12% cap rate (PV = NOI / Cap Rate), and now the investor is willing to pay about $833,000. External circumstances have not affected the operation of the property or the NOI. They have affected the rate of return—the so-called market cap rate—that the buyer will demand, and it is that change that impacts the market value of the property.

In short, the NOI expresses an objective measure of a property’s income stream, while the required capitalization rate is the investor’s subjective estimate of how well his or her capital must perform. The former is mostly science, subject to definition and formula, while the latter is largely art, affected by factors outside the property, such as market conditions and federal tax policies. The two work together to give you your estimate of market value.

Cash Flow and Taxable Income

So far, our discussion has focused on the meaning of NOI—what it includes, what it does not include, and what significance it has to your understanding of the worth of an income property. As Figure 4.1 shows, the topics of cash flow and taxable income are natural extensions of NOI.

FIGURE 4.1 Taxable income and cash flow.

When you look back at a year of operating your property, a reasonable question for you to ask is, “How much did I make this year?” The answer lies in a review of the property’s cash flow and taxable income.

NOI is the starting point of our discussion here. Once you know the property’s NOI, you branch off in one direction to figure its taxable income and in another to figure its cash flow.

As you’ll see shortly, these two branches eventually reconnect to give you your true bottom line. First, let’s look at these two branches to see how they differ.

Taxable Income or Loss

Both branches start with NOI. Remember that mortgage payments play no part in the NOI calculation, so it is now, below the NOI line, that you will at last take financing into account.

When you make your taxable income calculation, you can deduct only the interest portion of the loan payments. Likewise, if you earn interest (on your escrow account, for example), you must add that back into your income.

You also make deductions for depreciation and amortization. When you purchase a piece of investment real estate, you can’t just deduct its full cost immediately as an investment expense. Instead, you can deduct each year a portion of the value of the depreciable asset, until finally you have written off the entire amount. With real estate, you are allowed to treat the physical structures (i.e., the buildings) as the depreciable asset for tax purposes, but not the land.

(An editorial aside: The author, having learned the commercial real estate business in the Pleistocene Age, still uses the traditional term “depreciation.” In the Modern Age of unrelenting political correctness, you will frequently find this same concept referred to as “cost recovery.” Congress, ever the subtle wit, no doubt became uncomfortable with an economic term that conveyed the notion of unremitting decay and collapse and chose to replace it with one that conveyed a sense of a rise-from-the-ashes return to health and well-being. No political agenda here, of course. It is interesting to note that Congress could not let go of the term “depreciation recapture,” which seems to conjure up subliminal images of the taxpayer as escaped convict, once again ensnared.)

At this writing, you can depreciate a residential income property over 27.5 years and a nonresidential property over 39 years. Since not everyone buys or sells on the first of the month, the tax code tries to even matters out with a so-called half-month convention, which allows the taxpayer to claim only half the normal amount of depreciation in the month that the property is placed in service and half in the month when it is sold. Of course, the authors of the tax code could have made matters more precise by simply asking you to prorate your partial month of depreciation, just as your bank does with per diem mortgage interest when you buy or sell. But they didn’t.

Another item that affects your taxable income is amortization. It is important to understand that the term, as used here, does not refer to the principal portion of a loan payment. Instead, it refers to the process of taking a partial annual tax deduction for an item you are not allowed to expense in a single year. A good example of a cost that must be amortized is the premium you pay for securing a loan, commonly called “points.” You typically pay this premium in one lump sum on the day you close the loan, but you must amortize it over the life of the loan. So, if you take out a 240-month investment-property loan for $720,000 that requires payment of 2 points (2%, or $14,400), you can deduct $60 per month, or $720 for each full tax year.

You may also earn some interest income on your property bank accounts or on an escrow account that your lender may require for real estate taxes and insurance.

To review, your taxable income is your NOI less interest payments, less your allowable write-offs for depreciation and amortization, plus any interest earned (Figure 4.2).

FIGURE 4.2 Taxable income or loss.

Cash Flow Before Taxes

Cash flow is even more straightforward. As we suggested in the Introduction, think of it as your property’s checkbook. It is everything that comes in less everything that goes out. By starting with NOI, you have already accounted for all the rent revenue, credit losses, and operating expenses. Where else do you spend or receive money?

You make mortgage payments, and now you can count the entire payment amount. You may also make capital improvements to a property. An improvement prolongs the life of a property. It’s different from a repair, which maintains, rather than increases, that life expectancy. The cost of the improvement affects your cash flow as soon as you spend the money, even though you may typically have to write it off over 27.5 or 39 years.

Again, here you may earn interest income on your property bank accounts, which also adds to your cash inflows.

The short version of our discussion now boils down to this (Figure 4.3): To derive your property’s taxable income, you take its NOI, subtract everything that is properly tax deductible, and add any nonrental income such as interest. To calculate its cash flow, you take its NOI and subtract everything that was actually spent but not already accounted for in the NOI computation itself. Again, add any nonrental receipts.

FIGURE 4.3 Cash flow before taxes.

Cash flow and taxable income are closely related but still have important differences. Cash flow is real. Money comes in; money goes out. You earnestly hope the difference will always be a positive number, and if it is, you can take it with you; you can even spend it.

With all due respect to the considerable industry that is built around tax planning and preparation, taxable income is not quite so real. It’s whatever the tax code du jour says it is.

If tomorrow the House of Representatives should decide that the useful life of commercial real estate ought to be 100 years instead of 39, then your property’s taxable income will rise without your experiencing a single additional dollar in rental income. Why? Because the longer write-off period would mean smaller annual deductions for depreciation, and fewer deductions mean higher taxable income—despite the fact that your gross and net incomes remain unchanged.

Likewise, if mortgage interest were no longer deductible, the effect of the mortgage payment on your cash flow would remain unchanged, but the effect of the lost deduction would be to increase your taxable income and hence your taxes.

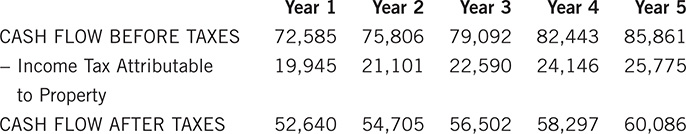

Cash Flow After Taxes

All this talk of deductions brings you to the fulfillment of an earlier promise, to reconnect the two branches of our diagram. Up until now, we have been discussing cash flow before taxes (CFBT), but a more meaningful bottom line to you as an investor may be cash flow after taxes (CFAT, Figure 4.4).

FIGURE 4.4 Cash flow after taxes.

While taxable income is a somewhat artificial notion, the tax liability it provokes feels very real indeed. Taxable income creates one last cash flow item: income tax, which must be subtracted from your CFBT to give you your bottom line, CFAT.

Again, recall our discussion in the Introduction of the four ways to make money in real estate. Your taxable income may be negative as well as positive. If it is negative, then it may actually result in a negative tax liability and can increase your CFAT by sheltering other earnings.

A Case Study

A comprehensive example will demonstrate how all these numbers interact. For readability, let’s make projections that go out just five years. If you would like to work out any of the calculations in longhand, you’ll find forms for taxable income and cash flow in their respective chapters in Part II.

In this analysis, you plan to acquire a small strip shopping center for $1,250,000. Your cavalier attitude toward debt leads you to take on three mortgages. The first mortgage is for $720,000 with an interest rate of 8% for 20 years. You must pay 2 points ($14,400) to secure the loan. The second mortgage is a 10-year note for $100,000 at a fixed interest rate of 9%. It also requires 2 points (in this case, $2,000). The third loan is from the seller for $10,000, interest only, at 10% fixed and due to mature in 10 years. It requires a single interest-only payment annually until then.

For purposes of calculating depreciation, you look at the municipal tax assessments for the land and the building and conclude that 72% of the property’s value lies in the building and the remainder in the land. Therefore, you judge, reasonably enough, that the amount that can be depreciated is 72% of the $1,250,000 purchase price, or $900,000.

The property has an annual gross scheduled income of $208,200 and annual operating expenses of $40,900 for the first year of your projections. You expect both income and the expenses to increase at a rate of 2% per year. You leave an allowance of 3% for possible vacancy and credit loss.

Sorry to get personal, but we also need to know your marginal tax bracket (that is, the rate at which your next dollar of income will be taxed). You whisper it to us discreetly, but we publish it here for the world to see: 28%.

Now you can begin to sort out all this information. What is the NOI for years 1 through 5?

In the first year, your property’s gross scheduled income is $208,200. From that amount you subtract a 3% allowance for vacancy and credit loss to get the gross operating income. Next, you subtract $40,900 in operating expenses to find a first-year NOI of $161,054.

To calculate the NOI for the next four years, you’ll first need to increase the gross scheduled income by 2% for each year. Once you have done so, you can then compute the vacancy and credit allowance, which is 3% of each year’s scheduled gross. After that, figure out the operating expenses by taking the first-year amount of $40,900 and increasing it 2% per year (it’s that old compound interest again). Finally, subtract the expenses from the gross operating income to get your NOI.

All that was easier to do than to say. Now, from the NOI, you can follow the first branch of our diagram, which calculates the taxable income. Before you do the math, look at a more detailed representation of that branch:

NET OPERATING INCOME

– Interest, 1st Mortgage

– Interest, 2nd Mortgage

– Interest, 3rd Mortgage

– Depreciation, Real Property

– Amortization of Points, 1st Mortgage

– Amortization of Points, 2nd Mortgage

– Amortization of Points, 3rd Mortgage

+ Interest Earned

TAXABLE INCOME

From your NOI, you subtract anything that is tax deductible. Mortgage interest falls into that category, so you subtract the interest from each of the three mortgages. Depreciation, even though it is not cash out of pocket, is also deductible. Similarly, you can deduct a portion of the points you paid to obtain each mortgage. If you had income that was not from rent—typically, interest earned on the property’s bank or escrow accounts—that interest needs to be added in as additional income.

(A shameless self-promotion: If you go to realdata.com, you can purchase software that performs calculations like these and produces elegant presentations. This fact absolutely does not excuse you from reading the rest of this book, however. No amount of automation will benefit you if you don’t first get a grip on the basic formulas and techniques presented here.)

Now let’s look at this same list with the amounts calculated and filled in:

In regard to the mortgage interest paid out each year, there are several ways to calculate the amount manually or with Microsoft Excel (see Part I, Chapter 3, and Part II, Calculations 28 through 30). You can also download a loan amortization schedule to create a table that will show monthly and annual principal and interest (see http://www.realdata.com/book).

Note, however, that one of the mortgages is not amortized. The third mortgage in this transaction is interest only, paid annually. This is a calculation you can do in your head: $10,000 at 10% requires an annual payment of $1,000.

For purposes of depreciating a piece of investment real estate, you must first identify it as residential or nonresidential. This is a shopping center, so clearly it is nonresidential. You then depreciate it over what the tax code defines as its “useful life”—which, as you might guess, is an artifact of the tax code and has nothing at all to do with its real useful life. If you were to hold and depreciate the property for decades and then sell it to a new owner, that owner could start over with a brand-new useful life.

As of this writing, you depreciate residential property over 27.5 years and nonresidential over 39 years. Although they have been at this level for over several decades, be aware that these periods could change with any revision of the tax code.

You’ll recall that we said the depreciable basis of this property is $900,000. Because it is nonresidential, you need to depreciate it over 39 years. Divide 900,000 by 39, and you get 23,077, which is what you find in the example above for year 2 and after. But what about year 1? The “half-month convention” allows you to take only one-half of the normal depreciation for the month that you place the property in service. In year 1, therefore, you are entitled to 11.5 months of depreciation. One month of depreciation would equal the yearly amount divided by 12 (23,077 / 12), or 1,923.08. Multiply this by 11.5 months, and you get the depreciation for year 1 as shown, 22,115.

You paid 2 points on the $720,000 first mortgage for a total of $14,400 (720,000 × 0.02). This is a 20-year note, so you divide the total amount of the points by 240 months to find that you can deduct $60 each month or $720 per year until you have written off the full amount. You refer to this process as “amortizing” the loan points—deducting them not in full when you spent the money, but over time for the length of the loan. If you were to retire the loan before the 240 months ran out (by refinance of the mortgage or sale of the property), you could, under the tax code at this writing, deduct the unamortized balance of the points in the year that you paid off the loan.

The points for the second mortgage, of course, work exactly the same way.

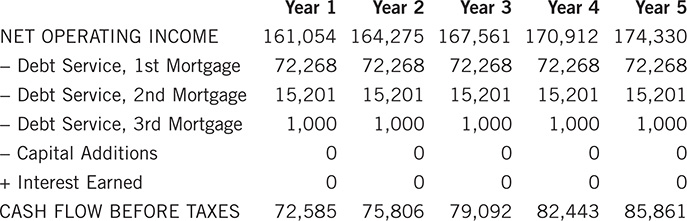

Now let’s look at what happens in the cash flow branch. First, the categories:

– Debt Service, 1st Mortgage

– Debt Service, 2nd Mortgage

– Debt Service, 3rd Mortgage

– Capital Additions

+ Interest Earned

CASH FLOW BEFORE TAXES

Again, you start with the NOI. From that amount, you subtract the full amount of all mortgage payments, not just the interest. You did not choose to make any capital additions to the property, but if you had, then you would subtract them as well. You didn’t earn any interest on your property checking or escrow accounts.

In this example, you have the same NOI as before, of course, and your disbursements are the payments you make on three mortgages. Using the techniques you learned in the previous chapter, you can calculate the monthly payment for each of the two regularly amortized mortgages. Once you have the monthly payment for each, you simply multiply it by 12 to find the total debt service for each year. The third mortgage is interest only, so the annual debt service is exactly the same as the annual interest.

You subtract these mortgage payments from the NOI to leave you a positive CFBT in year 1 of $72,585. In subsequent years, the debt service remains constant, but your NOI increases, so you forecast that your cash flow will increase every year.

To get to your bottom line, you need to estimate your income tax liability in order to figure your CFAT. The calculation of the potential income tax liability can sometimes get complicated, involving issues like passive loss limitations and suspended losses, but we’ve chosen to make this case study fairly straightforward. As illustrated in Figure 4.4, you have to go back to the taxable income calculation in the previous table to retrieve the year 1 taxable income of $71,231. From that, you calculate the income tax liability that is attributable to your ownership of the property. Multiply the taxable income of $71,231 times your marginal tax bracket of 28% for an estimated tax liability of $19,945.

In short, if you achieve your projected year 1 CFBT of $72,585, you’ll have a tax liability of $19,945, leaving a CFAT of $52,640.

Note that you expect to pay more tax each year because the property earns more taxable income each year. However, your CFBT is growing faster than your tax liability, so your bottom line—the CFAT—becomes greater each year.

Without a positive cash flow, your property becomes like the plant in Little Shop of Horrors, greeting you with a baritone “Feed me” at every turn. A positive cash flow is important to all investors and essential to some. Is CFAT, then, the end of your continuing saga of investment analysis? Not at all. Next, you’ll look at the ultimate resale of your property and at how value impacts the overall quality of your investment.

Resale—How to Forecast the Appreciation Potential for a Property

We’ve talked about net operating income, taxable income, and cash flow. One topic that sometimes gets less attention than it deserves from beginning real estate investors, however, is resale. Some investors tend to be dismissive, looking at resale as speculation, but many others simply find it difficult to focus seriously on the matter of selling a property they haven’t yet purchased. It may take a little extra discipline to work a consideration of resale into your investment mindset, but it is just such discipline that often separates the successful investor from the sorry. Attention to what your property may be worth in the future is no less important than your concern for its value on the day you purchase it.

You care about the potential cash flow, the financing, the operating costs, and the tax benefits. You’d better care also about whether the property will be saleable after you buy it. Often one hears, “Yes, but I plan to keep it for 15 years, or until my toddlers graduate from med school, or until the Federal Reserve Board performs a synchronized swimming exhibition on reality TV.”

That’s fine; may all your plans go without a hitch. But what if you need to sell this property next year? What if a better opportunity comes along in five years, and you want to cash out?

The world may not be perfect, but at least it’s flat—as in “level playing field.” You can reasonably assume that if you would scrutinize a property’s income, operating expenses, financing, and various measures of return before you purchase, then tomorrow some equally astute investor will apply a similarly jaundiced eye to your numbers when you choose to sell. It pays, therefore, to run tomorrow’s numbers today and to see just what this investment will look like to a future buyer.

So, what are the numbers that should concern you when you analyze the potential resale of an income property? The most obvious and the most important is the selling price. What will the property be worth in the future? With most income properties, you can estimate the value by applying a reasonable capitalization rate to the net operating income.

In brief, you first estimate the property’s NOI in the year of sale. Next, you have to estimate the capitalization rate (i.e., the rate of return) that the buyer would reasonably expect. The NOI is the amount of the return, and the cap rate is the rate of return. Hence, if the market expects a 10% return and your property produces an NOI of $12,000, your estimate of its selling price would be $120,000. Another way of articulating the algebra involved is to say, “$12,000 represents 10% of what?”

A curious phenomenon exists in the real world. Buyers and sellers can look at the same information and see different meanings. This, you may suspect, is the closest that commercial real estate will ever come to poetry. Not only might you have a different notion of “reasonable rate of return” as a seller, but you might also change your perspective on NOI. It is common for a buyer to estimate value by capitalizing the current year’s NOI and for a seller to capitalize next year’s expected NOI. The buyer often takes the position, “I am buying the income stream that just happened, and the property’s value is based on that income stream. If the income goes up next year when I own the property, that’s my business.” The seller, as a rule, will assert, “You didn’t own the building last year. You’re buying next year’s higher income stream. The value of what you’re buying should be based on that.”

Once you develop your estimate of the resale price, the rest of the analysis of resale is fairly straightforward. You will want to calculate the estimated tax liability at the time of sale. Then, with that number in hand, you can forecast the sale proceeds and the overall rate of return for the holding period.

Let’s revisit the property in our case study and see if you can estimate both its value to a new buyer and the cash proceeds you might expect from a sale to that buyer. The case study looked five years into the future, so let’s assume that you will sell the property at the end of those five years.

Start with an estimate of its selling price. The most straightforward approach is to capitalize its NOI. When you use a cap rate to forecast a property’s value at some point in the future, the first judgment you must make is to decide what rate of return (i.e., what cap rate) will investors then demand. Unless you recently traded in your laptop for a crystal ball, you don’t know the answer with certainty. You can, however, make a reasonable guess. As discussed in Chapter 1, you can find out what cap rate investors are typically achieving for similar properties today. Then you behave like a sensible and cautious adult, and you assume that you must use a slightly higher rate to estimate the value of your property in the future.

(The alert reader will recognize that, while we’re discussing how to estimate the value of a property five years into the future based on its income, the same approach—capitalizing the NOI—is typically one of the ways we would estimate what it is worth today. See Part II, Calculation 10.)

You do this because you don’t like unpleasant surprises. As the Rule of Thumb proclaims, the higher cap rate yields the lower estimate of value. Why? Because if the property generates a certain number of dollars of income (the NOI), the less you pay for the property, the higher the rate of return on your investment will be. The more you pay, the less the rate of return.

Your research shows that investors are currently buying properties like yours at an 11% capitalization rate. The formula:

Cap Rate = NOI / Value

expresses mathematically what we’ve been saying. If you made a $10 profit on a $100 investment, you would be able to say almost intuitively, “I made 10% on my money.” Perhaps without realizing it, you used the preceding formula.

Rate of Return = $10 profit / $100 investment

Rate of Return = 10%

With some minimal algebra, you can transpose the formula if you want to calculate the value of the investment:

Value = NOI / Cap Rate

Put away the folding money now and get back to your real estate. Say that your property has an NOI of $11,000. If investors are buying property at a 10% cap rate, what will they be likely to pay for yours?

Value = NOI / Cap Rate

Value = 11,000 / 0.10

Value = 110,000

But, as noted above, your research suggests that investors are demanding a higher rate today of 11%. What happens to the presumed value of the property?

Value = NOI / Cap Rate

Value = 11,000 / 0.11

Value = 100,000

As advertised, the value goes down because the investor must pay less for the property in order to get a higher rate of return from the same NOI. Now let’s apply this reasoning to the property in the case study. You want to sell it after holding it for five years. If you go back to the example, you’ll see that you forecast an NOI for year 5 of $174,330. You want to be conservative, so you assume that investors will expect a higher cap rate that year. Given an NOI of $174,330, what do you think an investor who expects a 12% cap rate would be willing to pay?

Value = NOI / Cap Rate

Value = 174,330 / 0.12

Value = 1,452,750

Rounded to the nearest thousand, 1,453,000

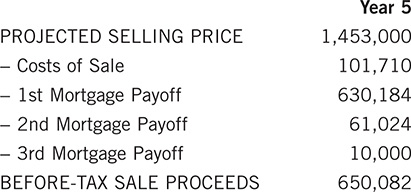

How much of that $1,453,000 will you get to carry home from the closing? Not all of it, of course, because you have debts and expenses to pay:

PROJECTED SELLING PRICE

– Costs of Sale

– 1st Mortgage Payoff

– 2nd Mortgage Payoff

– 3rd Mortgage Payoff

BEFORE-TAX SALE PROCEEDS

In this case, you have three mortgages to pay off. Remember that the third mortgage was interest only, so its balance at the end of five years will be the same as it was at the beginning—you’ve made no principal payments. In addition to the mortgages, you will incur some costs when selling the property. These will include legal costs related to the closing and a commission if you used a broker to help you sell.

Let’s fill in the numbers now and see what’s left in the till:

How does that compare with the cash you invested at the outset? You had to pay for the property and the loan points. You used three mortgages to cover some of that cost, and the balance was your cash investment.

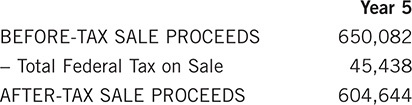

So, you went into this deal with $436,400, enjoyed some positive cash flows along the way, and walked away from a closing with a check for more than $650,000 before taxes. Not too shabby.

Speaking of taxes, how big a bite will the government take out of that check? The rules governing the tax on the sale of real estate are moderately complex and subject to change. If the author had a red flag (he does not), he would be waving it vigorously here. The discussion that follows will give you a general idea of how it’s done currently without getting bogged down in the fine points. That’s what you pay your accountant to do.

To figure the tax on the sale of income property, you must first figure the gain. The gain is the difference between the selling price and the property’s “adjusted basis.”

We talked about basis earlier in our discussion of depreciation, so what is the adjusted basis? Adjusted basis is the property’s original cost, plus capital improvements, plus closing costs and other costs of sale, less accumulated depreciation. Essentially, the adjusted basis is what you spent to purchase, improve, and sell the property less the amount you have already written off. If you sell the property for more than this amount, you have a taxable gain.

The adjusted basis calculation for the property in the case study looks like this at the end of the fifth year:

Keep in mind that under the current tax code, you can take only one-half month of depreciation deduction in the month that you dispose of the property. This rule mirrors the one that allows only one-half month when you first put the property in service.

What, then, is your gain when you sell this property?

This part of the calculation has survived quite a few changes in the tax code, so you can probably expect that it will hang around awhile longer. Nonetheless, you should never rely on permanence in regard to tax rules, so please heed the warning that we have included the calculations in the next section more for illustration than instruction.

In calculating your tax liability at the time of sale, there are certain deductions that may come into play. For example, you may have had operating losses in prior years that you were not allowed to take because they exceeded your “passive loss allowance.” If you could not deduct them earlier, you can deduct them at the time of sale. You may also have had loan points and leasing commissions that you’ve been amortizing (i.e., deducting over time). If you have an unamortized balance on any of these items, you can deduct it when you sell.

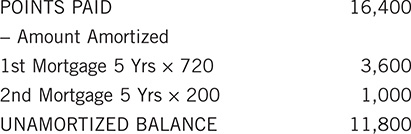

Your sample property does indeed have points that have not yet been fully written off. Recall that you paid $16,400 in points to obtain the first and second mortgages. You have been amortizing $720 of the first mortgage points each year and $200 of the points for the second mortgage. That means you’ve deducted $920 each year for five years, a total to date of $4,600. If the full amount of the points was $16,400 and you’ve amortized $4,600, you have $11,800 left to deduct. You can add that amount to your deduction for the fifth year because you are retiring the loan by selling the property.

Now you have enough information to compute the tax liability due on sale.

Under the current rules, you as a 28% bracket taxpayer would break your $214,752 gain into two parts: an amount equal to the total depreciation you’ve taken (which needs to be recaptured at an ordinary income rate, but not more than 25%) and all the rest. So you would break the gain into $113,462 taxed at 25% and $101,290 taxed at the capital gains rate (15% or 20% or sometimes even more under the tax code at this writing, and which could be affected by your modified adjusted gross income, tax bracket, holding period, and year of sale). And recall that you still have those amortized points ($11,800) that you can take as a deduction at your ordinary income rate.

If you find that confusing, you’re not alone. Take our earlier advice and have your accountant do this when it gets to be real. Our purpose for including it here is to close the circle and to show your ultimate bottom line at the time of sale, the after-tax sale proceeds.

In this chapter, you’ve developed a good understanding of what a property is really worth in terms of the cash flow and eventual sale proceeds that it can provide. Now it’s time to get out your yardstick and learn how to measure the quality of a real estate investment.