Introduction

The Four Ways to Make Money in Real Estate

Whether you’re an experienced income-property investor or a beginner just testing the waters for the first time, this book will tell you how to “run the numbers” on any real estate investment. It is designed to serve as an indispensable guide and reference.

Like all types of investing, real estate requires that you develop a proficiency with some basic measurements—rates of return, cash flows, and estimates of value, to name a few. The goal of this book is to explain how to make these calculations for virtually any income property and to explain the basic concept behind each calculation so as to make you a smarter investor. Without knowing these key formulas, you’re really just guessing when you try to figure out whether a given property is a good investment. You may think you have a profitable property because it generates excellent rental income, but when you examine it more carefully using some of the rules of thumb in this book, you realize that what you have is a loser.

This handbook covers topics such as:

• How to estimate the current and future value of a property

• How to read between the lines of what a seller is telling about his or her property

• How to forecast your revenue streams, expenses, net operating income, and cash flows from a property—before you buy

• How to use the “time-value-of-money” concept to help you make good long-term investment decisions

• How to compare investment opportunities

• How to calculate financing, rates of return, potential tax liability, and more

What Do Successful Investors Really Buy?

Do successful investors prefer properties in perfect condition or those that need work? Do they favor residential or commercial, city or suburban, brick or frame, or blue or gray?

While any of these choices (except perhaps the color) may fit better into a particular individual’s comfort zone, the true investor treats the physical property as a secondary issue. He or she is not so much interested in buying the property but in buying the property’s anticipated economic benefits—what is called the income stream.

To the extent that some attribute of the physical property or its surroundings will affect that income stream, then that attribute becomes meaningful. Will the arrival of a major new employer create an increase in the demand for apartments? If so, this may be the time to look at apartment buildings. Would the opportunity for increased rents more than offset the cost of rehabilitating a particular property? Perhaps you should look for a fixer-upper.

The prudent investor seeks a return on investment. To achieve that return, he or she has to look at the numbers carefully—at the current financial data and at reasonable projections of how the investment will perform in the future. As the preceding Rule of Thumb makes clear, no successful real estate investor buys a property—or worse yet, holds one too long—because of a sentimental attachment to that property. Decisions to buy and sell are based on financial measures, on the income stream, and on the return on investment that the income stream represents.

Begin your study of the concepts and calculations just as you would if you were constructing a new building. Start with the foundation: the four basic investment returns.

How You Make Money in Real Estate: The Four Basic Investment Returns

Virtually all the measures and concepts that we will discuss in this book connect to four critical elements that, to a greater or lesser degree, inhabit every income-property investment. They are the ways you make money with income property. You can call these elements the four basic returns:

1. Cash flow

2. Appreciation

3. Loan amortization

4. Tax shelter

Not every income-property investment will provide these returns in equal measure. Each property is unique and will blend the four benefits differently; some investments may even lack one or more. One property may give you a good annual cash flow; another may yield little or no cash from year to year, but offer the promise of a big payday when you sell. Nonetheless, these four returns compose the complete pool of potential benefits. The investment decisions you make will depend on your personal goals and on the strength of these various returns. If you understand where they come from and how to calculate them, then you’re well on your way to success.

From this point on, almost every calculation and concept we discuss will relate in some way to these four basic returns. Let’s look at them in greater detail now.

Cash Flow

Do you have a checkbook? If so, then you already understand cash flow. Money comes in; money goes out. When you want to know the balance in your checkbook, it doesn’t really matter where the money came from or where it went. All that really matters is how much came in and how much went out.

You’re interested solely in the flow of funds, hence the name “cash flow.” If you look at a particular period of time (12 months is usually a convenient choice), you’ll want to know if more cash comes in than goes out. If at the end of that time you can say that you took in more money than you spent, then you had a “positive cash flow” for the year. Another term you will sometimes see for positive cash flow is “net spendable cash,” which refers to the cash flow that is left over after you pay your income taxes on the property’s earnings. If a real estate investment has a positive cash flow (i.e., if there is money left over after all the bills are paid), that’s money you can take off the table.

On the other hand, if you have spent more than you took in, you had a “negative cash flow.” Nature abhors a vacuum (and banks aren’t too fond of overdrawn accounts, either), so a negative cash flow implies a deficiency that you have to do something about. If you have a negative cash flow in your personal checkbook, then you know you have to put money in from some other source, perhaps savings. If it’s your real estate investment that experiences the negative cash flow, then you have to make up the shortfall from funds outside the property account—in this case, your own pocket. A property with a negative cash flow doesn’t provide you with any spendable cash. On the contrary, it requires that you put more of your personal funds into the property to make up the difference.

Cash In

less Cash Out

= Cash Flow

Example. Let’s look at a basic and fairly typical example of cash flow from an income property. You own a six-unit apartment building. Two units rent for $800 per month, two for $900, and two for $1,000. All units are occupied, and everyone pays on time. Each month you make a mortgage payment of $2,800. For the year just ended, you paid $14,100 in real estate taxes, $3,800 for property insurance, $4,200 for maintenance and repairs, $800 for water, and $75 for miscellaneous supplies. Do the math:

Cash In

(2 × 800) + (2 × 900) + (2 × 1,000) = $5,400 per month

5,400 × 12 months = $64,800 per year

Total Cash Inflows $64,800

Cash Out

You have taken in more than you spent, so you have a positive cash flow.

You should note again that the source of the cash inflows and outflows doesn’t concern you when calculating cash flow. Inflows may come from rent, loan proceeds, vending machine revenue, or any property-related source. The same is true of outflows. Payments for operating expenses, debt reduction, or even construction of additional rental units all represent outflows that reduce your overall cash flow.

Appreciation

Every investor hopes to see a good cash flow from his or her property because that means the investment is providing some spendable cash each year. Not all properties generate a meaningful cash flow, however, and for those that don’t, the next most important of the four basic returns is appreciation. Not to be confused with what you wish you could get from your teenage children, appreciation is defined as the growth in value of a property over time.

The formula here is just as direct as that for cash flow:

Future Resale Price

less Original Purchase Price

= Appreciation

With cash flow, we asked if you had a checking account. Now we’ll ask if you have a savings account. If you do, you’ve seen appreciation at work. You put $1 into the account today. Interest, an engine of appreciation, causes it to grow over time.

The questions that should come to mind immediately in regard to real estate appreciation are, “How much growth?” and “How much time?” To answer these questions, you need to consider a more fundamental issue, “What causes a property to appreciate in value?” Several parts of this book will address that very question, so we won’t try to deal with it in depth here. In general, however, revenue—particularly net revenue (after operating expenses)—drives the value of income property. We’re returning to one of our basic principles here, that real estate investors really buy the property’s income stream. If you have more income stream to sell, you can expect to get more for it. Hence, the faster and the greater your revenue increases, the more likely it is that the value of the property will increase.

So, what makes revenue increase? Changing market conditions may make the property more attractive. An area that was once marginal may become fashionable, and consequently the balance of supply and demand shifts. General economic inflation may cause the cost of new construction to rise, putting upward pressure on rents.

External forces are not the only factors that can influence appreciation. You may make physical improvements to the property so that it can command greater rents. You may simply improve the management of the property, attracting and keeping better tenants, reducing vacancy losses, and minimizing wasteful expenditures.

You may not enjoy the benefit of appreciation until you sell, but when you do sell, the value of this benefit can be substantial. If this were a get-rich-quick book, we would probably talk about nothing else.

Example. You purchase a property for $1,000,000 and sell it at some future date for $1,450,000. What is the amount of appreciation?

The amount of appreciation is the difference between the selling price and your original purchase price, $1,450,000 less $1,000,000, or $450,000.

Loan Amortization

It’s really nice when someone else pays your bills. In effect, that’s what happens when you use a mortgage loan to help you purchase an income property. Consider a $1 million office building. You could write a check for the full amount, but, sadly, that would almost clean out your bank account. On the other hand, you could write a check for just $300,000 and get a loan for $700,000. That would leave you with enough money to buy two more similar buildings and still have change left over.

Of course, a loan requires payments, usually monthly. Where will the money come from to make these payments? Recall our earlier cash flow example. The mortgage payment was one of the cash outflows, and it was paid with the cash that came in. With most properties, rental revenue makes up all or nearly all of the cash inflow, so essentially it is your tenants who pay your mortgage.

Each mortgage payment you make includes both interest and principal. In a later section (Part I, Chapter 3), you’ll see more details about how to calculate the specific amount of each, but for now, you’re more interested in the concept. You use a mortgage loan to purchase the property. Each month your tenants give you the cash needed to pay down that debt. They are helping you buy the property.

Amortization is the liquidation of this debt by the application of installment payments over time (for the Latin scholars, think of “ad” [toward] and “mort-” [death]—killing off the loan).*

Debt Service (i.e., total mortgage payment)

less Interest Paid

= Amortization

You will usually look at income-property data on an annualized basis, so you can expect to see the term “annual debt service” (ADS). The ADS on a mortgage is the total of all payments you make in a year.

Example. You make monthly mortgage payments of $1,500. At the end of the year, your bank reports that you have paid $15,000 in interest for the year. What is your loan amortization for the year?

If you pay $1,500 per month, then your ADS is $1,500 times 12, or $18,000. You apply the formula:

Tax Shelter

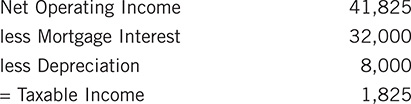

The last of the four basic returns is tax shelter. An income-property investment can shelter some of its own income from taxation and occasionally shelter income received from other investment sources as well. How does it do that? As owner of an investment property, you take in taxable rental income and pay out tax-deductible operating expenses like insurance and repairs (see Part I, Chapter 2, and Part II, Calculation 9, for a more detailed discussion), leaving you with a “net operating income” (NOI) on which you would expect to pay taxes. However, to promote the general economic benefits that tend to flow from real estate development (e.g., the creation of office and retail space, multifamily housing, etc.), the tax code permits further deductions.

The first of these deductions is for mortgage interest. Interest is really a cost associated with acquiring the property rather than operating it, and even though your tenants appear to be paying the interest along with the rest of your mortgage, the IRS allows you to deduct that interest.

The second source of tax shelter is through the depreciation deduction, which is now called cost recovery in the tax code as of this writing, but is still usually called depreciation by real flesh-and-blood investors. Even though the market value of the property is probably increasing over time, you can make the assumption that the buildings (but not the land) are, in fact, wearing out over time and becoming less valuable—and you can take a deduction for that presumed decline in the value of your asset. (In case you’re tempted to stop reading right now and run out to buy up the whole neighborhood, it’s only fair to warn you that what the IRS giveth, it at least partially taketh away later when you sell. Read more about how to calculate the depreciation deduction in Part II, Calculation 34.)

The exhilarating part about depreciation, if any part of the tax code can be so described, is that it is a noncash deduction. In other words, you get a deduction without writing a check. It does not affect your cash flow, and it is not an operating expense. It is a deduction that can shield some or all of your property’s year-to-year income from taxation. If the depreciation deduction is large enough, it can even exceed the amount needed to shelter the property’s own income and provide shelter for other investment income as well. In that case, the deduction creates what is effectively a cash yield of its own by reducing your other tax liabilities.

To anyone who has ever attempted to fill out a tax form, it should come as no surprise that you cannot find a nice simple formula for the tax shelter component of a real estate investment. Nonetheless, you can at least get a feel for the concept by following this path:

Income

less Operating Expenses

= Net Operating Income

Then,

less Mortgage Interest

less Depreciation (Cost Recovery)

= Taxable Income

Example. Let’s revisit the property you looked at in the preceding cash flow example. You can use the same rental income and operating expenses. You have rental income of $64,800 and operating expenses of $22,975. (Neither the entire mortgage payment nor just the interest portion is an operating expense, a concept you’ll learn more about in Part I, Chapter 4.)

You need to know your mortgage interest and allowable depreciation in order to complete the calculation. Say that your mortgage interest for the year is $32,000 and your deduction for depreciation is $8,000.

Recall from the cash flow example that this property has a positive cash flow of $8,225. You can put $8,225 (less income tax payable) in your pocket, but you now see that you have to pay taxes on only $1,825. This is good. It’s a tax shelter at work.

Summary

The foundation is now in place. You understand that every income property has the potential to provide you with as many as four different returns: cash flow, appreciation, loan amortization, and tax shelter. Cash flow is the money you have left after paying all your bills; appreciation is the growth in equity caused by an increase in the property’s value; amortization represents the growth in equity caused by the gradual paydown of your mortgage; and tax shelter signifies the property’s ability to shield from taxation some of its own income and perhaps even income from other investments. From this point on, almost every concept and calculation we discuss will bear some relationship to one or more of these four basic returns.

You’re ready to get serious about real estate investing.

*Note that there is also a tax-related concept called amortization, which we will discuss in a later chapter.