Chapter 7

![]()

Macrolevel People Principles: The Context for Exceptional People to Provide Exceptional Service

Organization is a process, not a structure. Simultaneously, the process of organizing involves developing relationships from a shared sense of purpose, exchanging and creating information, learning constantly, paying attention to the results of our efforts, coadapting, coevolving, developing wisdom as we learn, staying clear about our purpose, being alert to changes from all directions . . . These are the capacities that give any organization its true aliveness, that support self organization.

—Margaret J. Wheatley, author of Finding Our Way

THE ROLE OF ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN

I seemed to have missed discussing organizational design in The Toyota Way. Interesting, since I taught organizational theory and design for over 30 years at University of Michigan. Perhaps this is because historically the organizational chart has not been emphasized in Toyota. A Toyota product development engineer once shared his business card with me and laughed as he said, “It is in Japanese; I am sorry. It says my name and ‘engineer.’” His job was to work really hard to accomplish whatever challenge he took on, which varied over time as different needs arose. Working in what some call the white space—the spaces between boxes on the organizational chart—is more valued at Toyota than doing a great job inside your box.

Therefore much of the effort in Toyota is on setting challenging goals to achieve breakthrough business objectives, but equally important is to develop people to live the Toyota Way of thinking and acting. It is very fluid and takes place within a loosely defined organizational structure, in the spirit of what Margaret Wheatley talks about as “the process of organizing.” Toyota is more interested in “struggling to find our way” to the next big challenge than executing plans and policies within a tightly defined structure. On the other hand, under Akio Toyoda, organizational design became more important to Toyota. In just a few years, he led several reorganizations. These included a reorganization by region to create more self-reliance, with local CEOs appointed (in the past a Japanese executive was always at the top of the region). Then in 2016 Toyota reorganized again, this time by product family, in order to become more nimble and respond more quickly to the environment.

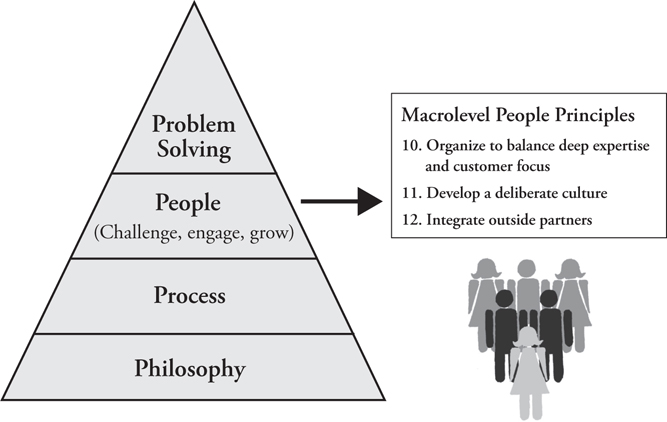

In this book we’ve decided to talk about macrolevel people principles because we believe they can be important to lean transformation. Perhaps in some sense it matters more in services where there are not clear physical boundaries for making things. The macrolevel creates one context in which members “find their way.” We have summarized the macrolevel through three overarching principles (see Figure 7.1):

Figure 7.1 Macrolevel people principles

![]() Organize to balance deep expertise and customer focus.

Organize to balance deep expertise and customer focus.

![]() Develop a deliberate culture.

Develop a deliberate culture.

![]() Integrate outside partners.

Integrate outside partners.

PRINCIPLE 10: ORGANIZE TO BALANCE DEEP EXPERTISE AND CUSTOMER FOCUS

The Challenge of Organizational Design

It was my first meeting with a new client. The COO pulled out an organizational chart to familiarize me with the organization’s structure. He grunted and took out a marker. With an undertone of frustration, he began slashing, making new lines and boxes, and crossing out names and adding new ones. “This is a bit out-of-date, but it gives you an overview of our organization,” he explained almost apologetically. I was not sure whether to make a mental note that this organization could not even keep up its org chart or be relieved that the org chart was not important enough to keep up-to-date.

Organizational structure has become somewhat of a joke popularized by comics like Dilbert. One now infamous quote, supposedly from Gaius Petronius Arbit in 210 BC, was actually published by an American journalist in Harper’s Magazine in 1957. It continues to circulate widely, and people smile and nod. It hits home:

We trained hard, but it seemed that every time we were beginning to form up into teams, we would be reorganized. I was to learn later in life that we tend to meet any new situation by reorganizing; and a wonderful method it can be for creating the illusion of progress while producing confusion, inefficiency, and demoralization.

There is widespread ambivalence, or even hostility, when it comes to the famed organizational chart. So many of us have lived through yet another reorganization that seems pointless and creates frustration and fear, while its architects were certain they were revolutionizing the organization to focus on the right things. While Margaret Wheatley wants us to understand that “organization is a process,” the organizational chart presents a static structure. It provides a rough map of reporting relationships and who works together. A map gives you names and locations of places. We get some sense of place but know almost nothing about the big city over there, or the small village here, or the experiences of those parking on that bluff. However, although the organizational chart may be lifeless, it tells us something about how the organization sees itself, and as we all know, a picture is worth a thousand words.

What we can really learn from the organizational chart is the perspective of leaders about what they are trying to accomplish through a particular way of organizing—the purpose. Is it telling us about reporting relationships—who does performance reviews of whom and who has formal authority? Is it telling us about standard communication patterns like “follow the chain of command”? Or does it depict a chain of processes that add value to our customer? Sometimes in Toyota the organizational chart is flipped upside down with the value-added workers at the top, an image suggesting those closest to the customer are at the top, served by their leaders whose only influence on the customer is indirect through the value-added workers.

Common Types of Organizational Design

Functional Organization. As Frederick Taylor was working to develop scientific management at the microlevel of individual workers, there were similar efforts to develop a scientific approach to macrolevel organizational design. One of the leading figures in this body of work was Henri Fayol, who worked his way up as a mining engineer to become the managing director of a large mining company. He retired and became a scholar, writing about what he learned as an executive.1 He approached the task as a scientist and developed 14 principles of management (sound familiar?). Like Taylor, he was searching for the one best way to organize. He found it in traditional command-and-control principles such as:

![]() Unity of command. Subordinates receive orders from one and only one boss.

Unity of command. Subordinates receive orders from one and only one boss.

![]() Authority. Power to give orders and exact obedience.

Authority. Power to give orders and exact obedience.

![]() Division of work. Organize by specialty.

Division of work. Organize by specialty.

Fayol did allow for some flexibility in the application of the principles depending on the situation. Nonetheless, the organizational design that arose from his principles was the command-and-control, functional organization. This is still with us today in most large organizations.

The functional organization puts people together by purported expertise—all the accountants under an accounting boss, all the architects under a managing architect, and so on. The idea is to build expertise and exercise control. The accountants will share practices and learn from each other. The accountant boss will know what the individual accountants are supposed to do and how they are performing. In a command-and-control environment, perhaps the latter is more important—knowing enough to control the people who report to you.

The problem is that departments become like little castles with moats around them, fighting for resources to take home and defend against other functional groups (see Figure 7.2). People focus on climbing the functional ladder, and in many cases in this organizational structure, the poor customer seems to be an afterthought. There is a huge amount of waste between departments, and there are often competing priorities between functions.

Figure 7.2 Departments are like castles

Customer-Facing Organization. To become customer focused, we often see organizations flip from a functional to a product organization. In order to do this, they define product or service groups and create vice president or director positions that might even have profit and loss accountability. They might split up customer bases by commercial versus private home offices, region, or size. There are endless ways to slice and dice the customer base. The point is for all the specialty functions that are needed for a customer base to align toward customer service. At the same time the organizations may be parsed into smaller organizations that run like minibusinesses, with accountable leaders who think and act like CEOs.2 This might also be thought of as organizing around value streams.

Matrix Organization. The customer-facing organization, or organizing by value streams, seems like the ideal structure; yet we have seen cases where it limits people development. Consider Chrysler before it was taken over by Daimler. Chrysler had made dramatic improvements in the appeal of its vehicles by transforming product development from a purely functional organization to a product organization that the company called “platform teams.” The company was reorganized around a set of platforms—large cars, small cars, trucks, minivans, Jeeps. It built a brand-new R&D center in Auburn Hills (Michigan) arranged so hundreds of engineers representing all the functional groups could sit on the same floor of the building to develop vehicles for a common platform. Chrysler even had financial analysts and purchasing representatives assigned to the teams (dotted-line reporting). It literally erased the functional organization and replaced it with the customer-facing platform teams leading to a rapid boost to the desirability of the company’s vehicles and sales. Unfortunately, as time went on, Chrysler realized it was losing functional depth—engine engineers were not learning from each other, body engineers were not learning from each other, and so forth. The company tried “technology clubs” so that functional groups could compare best practices, but they rarely met and it did not work. People focused on where their core work was and on the people they reported to. After about a decade, the company began to shift toward a matrix organization.

Toyota has used matrix organizations for decades. In product development, the functional groups, like body engineering and chassis engineering, report to a general manager within their technical specialty. The general manager is responsible for developing engineers with deep technical skills, assigning them to projects, and doing their performance reviews. The engineers work on development projects, reporting to a chief engineer for a vehicle, like Camry. The chief engineer is the CEO of that vehicle program and is, in essence, renting the engineers as contractors. Although the chief engineer works to develop the engineers as well, the chief engineer does not want to be distracted by personnel administration issues. This reporting structure works extremely well in large part because of mutual respect between the chief engineer and general manager of the function. The chief engineer trusts the general manager to provide highly developed engineers, and the general manager sees the chief engineer as the most important customer. In this way, matrix organizations seem to be the best of both worlds, and they can be seen all over Toyota.3

In Toyota Culture we describe how the human resource department at Toyota’s manufacturing operation in Georgetown, Kentucky, faced a major crisis when a number of female supervisors were sexually harassed. This led to deep reflection, and management concluded it was a failure of HR to build trusting relationships with team members on the factory floor. One result was to move HR professionals to the factory floor and make them responsible for a geographic region of the factory. Before this, the HR professionals had hard-line reporting relationships to human resources and dotted-lined reporting relationships to manufacturing. Now it was reversed: the primary reporting relationship was to the general managers in the factory so they could focus on building relationships in a specific part of the factory. It made a large difference in rebuilding trust and developing a strong connection between the people in human resources and their core job—developing people; but like any reorganization, it does not fix all the human resources problems for all time. For example, later in that same plant, when Gary Convis became president, he found weaknesses in human resource development because many key people had been hired away by other firms. He had to mount yet another major effort to develop leaders, even bringing in people from the outside.4

Matrix organizations “seem” to be a win-win, but in reality they are very difficult to manage. Now instead of having one boss, team members have two or more, which can lead to confusion and conflicting direction unless (1) the bosses communicate effectively, (2) they are aligned toward common goals, and (3) they respect each other. Toyota works hard to develop these types of relationships so it can make them work, but many other organizations, which do not spend as much time developing people, find it a very difficult structure to manage.

Networked Organization. This is one of the newer forms and appears to be loosely structured anarchy. Empower people, make the organization’s purpose clear, and allow them to ebb and flow with those they need to work with on their own. Remove barriers to effective communication. Do not presuppose there is a best way of organizing on any given day.

In principle this seems utopian, but we have seen it devolve into chaos. One company that is making it work is Menlo Innovations, as we will discuss later in the chapter. Menlo’s CEO, or formally “chief storyteller,” Richard Sheridan, likes to say that when he and his partners formed the company, they forgot to create an organizational chart and assign people to bosses. He says there are no bosses, only people doing work for customers.

At Menlo there is evidence of a high-performing networked organization. For example, programmers with a huge range of experience pair together to write code, and the pairs change every week. Calling a meeting is as simple as shouting out in a big room where everyone works, “Hey Menlo!” The response will be everyone shouting back, “Hey Jeff (or fill in name)!” Then you are on the spot to say what you have to say or ask what you want to ask.

On the other hand, Menlo actually has very clear structures, and there are many of them. Pairing is not a choice of people floating around a room; it is a formal requirement to write code. Pairs are assigned every week by a manager, not self-selected by participants. Rich Sheridan can call himself what he wants, but he and two partners are the senior executives, both formally and spiritually. Nonetheless, Menlo functions as a highly customer-focused and productive custom software house without a lot of evident hierarchy and with clearly defined roles and responsibilities that do not appear on organizational charts.

While organizational structure matters, we still believe that how people think about customers and their work and their relationships with others, and how they think about the purpose of the organization and where they fit in, is far more important than where they sit in the organization. The most important thing is to focus intensely on understanding changing customer needs and work to align all the people in the organization in ways that allow them to serve customers to fulfill the organization’s purpose. In that way, customer focus and deep expertise remain balanced across the organization.

ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN AND HIGH-PERFORMANCE ORGANIZATIONS

In the 1980s I helped facilitate “open-systems workshops” with senior managers that started with identifying key environmental changes that would affect the organization, then defining the organization’s purpose, then understanding the fit between the people, technology, and organizational systems. This led to envisioning a desired future. These workshops were effective in getting people to think about how to design their internal organization to fit the organization’s purpose and environment. The focus was mainly on the human system, and the solution almost always was to develop some form of self-sufficient teams with all the functions needed to accomplish the work. For example, if a manufacturing group needed operators, supervisors, quality experts, manufacturing engineers, and maintenance to function, an attempt would be made to assign all these functions to the team. Unfortunately, there was a gap between the thinking and the doing, and the teams often did not have the leadership skills to perform at a high level of efficiency and effectiveness.

More recently there have been efforts to combine the macroview of open-systems theory with the microview of lean thinking, incorporating concepts like standard work, andon, visual management, and problem solving into self-sufficient teams.5 Some companies that follow the high-performance organization approach have embraced the improvement and coaching kata that we will detail in Chapters 8 and 9, and the daily process of developing people can help bring the concept of a self-sufficient team to life.

Elisa Reorganizing Around Value Streams

Elisa is a provider of telecommunications services, one of the best in service excellence in Finland.6 The company had different functional groups supporting different services—cable TV and Internet, wireless phones, and sales of devices. Customers expect their service to work on demand every time. If there is a failure, they want it to be fixed correctly and at lightning speed. Elisa needs great technology and great people who can maintain and improve the technology, and it needs well-informed customer service representatives who clearly and efficiently walk customers through various technical processes. The company falls mainly in the category of mass goods distribution (Internet, phone, cable, hardware).

Elisa went through a major transformation when it realized that many parts of the company were broken and customer satisfaction was disturbingly low. Management used all the principles we talk about in this book to increase the level of service quality, with Toyota as a model. The people in the company put a good deal of effort into improving the technological infrastructure, the types of physical systems that are more like manufacturing. They also worked intensely on customer-facing services. Elisa improved markedly on all key performance indicators. For example they achieved 4 out of 5 on an empowerment measure and reduced the number of network disruptions by 30 percent while the network was growing. In 2014 Elisa was honored as the best B2B sales organization in Finland by the Finnish Quality Centre. Profits have grown steadily year after year. But it was not profits that drove the transformation—it was customer satisfaction and a philosophy of engaging associates in a journey toward excellence that drove profits.

Elisa was fortunate to have a visionary CEO who was committed to the values of the high-performance organization. He was passionate about providing excellent customer service and about developing people. In 2009, Petri Selkäinaho, vice president of business development, took over the leadership of Elisa’s transformation to business excellence with Toyota as the model. Petri started to work with the senior leadership team teaching lean concepts and problem-solving methods. This started their lean transformation. In 2010, Elisa’s lean transformation was broadened including training all managers in problem-solving methods. This training was later made available and recommended for all personnel, and Elisa developed facilitation methods, e.g., for “learning from mistakes” and “learning from success.”

Petri then recommended finding help in identifying their core business processes and brought in Kai Laamanen who was skilled in facilitating macro-redesign to achieve high-performance organizations. Kai focused on the bigger-picture level using the HPO approach. Kai Laamanen helped Elisa to look beyond the functional organization and identify the core customer-focused business processes, sometimes called value streams. Each value stream was assigned to an executive in charge, and Kai led workshops with executives who defined in greater detail their core process. Following this Petri led them in improvement workshops to drive to targets for customer satisfaction, quality, and efficiency. The executives were taught the PDCA process—investigate the current condition of each business core process, set targets, identify improvement actions, lead implementation of those actions, check on results, and reflect on what was learned.

It was the Elisa executives who actively led the improvement process rather than delegating it or outsourcing it. For example, the consumer services team found that a top customer complaint was billing errors. The team went to work to eliminate these errors using data and solving problem after problem while customer satisfaction quickly rose.

The combination of macro organizational change and local development of people as problem solvers turned out to be a winning combination. Customer satisfaction steadily increased, leading to the national Finnish award. It became clear to me that the broad organizational design approach of HPO, with the right leadership, could be complementary to the lean approach of developing people to continually improve processes.

PRINCIPLE 11: DEVELOP A DELIBERATE CULTURE

The Role of National Culture

Let’s start with a basic truth. Culture is darn complex. Culture refers to shared values, beliefs, and rules of behavior. Try to get any two people to think alike and then multiply that by 10, 40, 10,000, and we get a sense of the complexity. There is far more diversity of thinking in any collectivity of people than we want to accept. And to make matters worse, people come and go, and some of those who stay have the audacity to change their thinking over time. In some ways culture is a theoretical concept that does not really fit the vagaries of the real world.

On the other hand, culture seems to be a powerful construct. On the whole, looking at central tendencies, we can see large differences across regions, nations, and different organizations within nations. Anyone spending time in other countries will quickly notice vast differences. One of the most comprehensive studies that quantifies national culture was led by sociologist Geert Hofstede over decades. He identified six dimensions that distinguish national cultures, and on his website you can select from among many different countries and get a country’s scores on these dimensions and a description for that country, along with comparisons.

We will focus on three of Hoftstede’s broad cultural dimensions that seem particularly relevant to lean—individualism-collectivism, long-term versus short-term orientation, and uncertainty avoidance versus risk taking. One of the concerns we repeatedly hear in companies looking to adopt some version of lean is that there is something peculiarly Japanese and Eastern about a continuous improvement culture that cannot be transplanted to the West. Let’s compare Japan with the United States, one of the most Western countries (see Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3 A comparison of the national cultures of the United States and Japan

Source: http://geert-hofstede.com/countries.html

Japan, like other Asian countries, ranks relatively high on collectivism. Contrast that with the United States, which is among the most individualistic countries in the world. The strong American value of individual rights and freedom from control by organizations (or government) makes Toyota Way culture difficult to imitate. Working in teams, identifying with the organization’s purpose, and following standard work are difficult. Early in the 1980s when U.S. auto companies were studying the Japanese companies, we would hear derogatory remarks like “We do not want to be an army of obedient robots like the Japanese.” The Japanese all wore the same uniforms, they exercised to music at the same time in the same way, and they sang the company song. They acted like a collective—something totally alien to American workers (though not so different for those at Menlo).

We described long-term thinking as the foundation of the Toyota Way. Having a strong sense of purpose focused on achieving something great for customers and society depends on long-term thinking, as does developing people patiently. The United States is relatively weak on long-term thinking, and Japan is very strong.

Complementing the individualistic tendencies of American culture is the tolerance for uncertainty. In combination, individualism and risk taking may be a reason for the success of entrepreneurial business start-ups in the United States. In many ways becoming an entrepreneur, earning riches, and doing it our own way without a boss is the American dream.

The Japanese are quite averse to uncertainty, which may be a reason why so many go to work for a large company for life and strongly identify with that company. Japan is a country fraught with uncertainty. It is a small island nation with few natural resources and is regularly buffeted by environmental threats including earthquakes and tsunamis. The Japanese must struggle to maintain a balance of international trade that depends on producing innovative, high-quality products. It is a matter of survival to gain some modicum of control over the environment. A Toyota mantra is “We defend our own castle,” which means the people at Toyota act as though they are self-sufficient as a company and must learn to navigate the rocky environment, gaining as much control as possible over their own destiny. Through collective action Toyota has conquered a myriad of threats from the environment and against the odds has become one of the world’s leading companies.

The Role of Organizational Culture

Organizations are said to have their own culture, to some degree independent of the national culture. Toyota’s culture is reflected in the artifact of the Toyota Way 2001 house. The purpose is contributing to society and customers, which in turn will lead to revenue to sustain the economic well-being of the company. The people at Toyota value both respect for people and continuous improvement and believe this is the only true path to sustainable growth. They believe challenge, kaizen, go and see firsthand, teamwork, and respect are the way to develop people so that they can meet the many challenges thrown at them by a complex and sometimes even hostile world.

These values and beliefs in Japan are all supported by the collectivist culture, long-term thinking, and a desire to avoid uncertainty by controlling whatever is possible to control. Since Toyota considers culture the source of its competitive advantage, the company is devoted to building its culture any place it sets up shop. Accepting that its culture was peculiar to Japan and could not be established in other countries would have meant giving up. And that would have meant that Toyota could not become a global company. Therefore the company accepted the challenge of developing the Toyota Way throughout the world.

For the most part it has succeeded. How? Through working hard, experimenting, learning, and above all persevering. A pivotal learning point was at NUMMI, the joint venture between Toyota and General Motors in California. Toyota set up the joint venture for the purpose of learning how to establish its culture with Americans. If it could do it in the United States, it could do it anywhere.

The company did not leave the culture to chance, but invested heavily in NUMMI in order to learn. The people at Toyota carefully selected American managers who seemed to fit Toyota’s culture, intensely socialized them first in Japan and then at NUMMI by sending over a Japanese coordinator for every executive and manager and Japanese trainers for group leaders and team leaders. The mentors coached daily, and Japanese coordinators called the parent company in Japan every night to report on what they had learned. They did not try to transfer every aspect of their culture in Japan, adapting some aspects to local culture. When they got resistance, they reflected, tried to understand the cause, and experimented with a variety of countermeasures. Again, this was one-on-one mentoring of all leaders for years!

One senior Japanese leader explained that his biggest challenge was establishing a culture of openly discussing problems. At first he would do what he was used to doing in Japan, which is ask everyone he was coaching, “What is the problem?” Americans responded defensively, even with hostility: “Are you saying I have a problem?” He would explain that “we all have problems, and by addressing them that is how we improve.” No luck. After deep reflection and some tutoring by the American leaders, the Japanese mentors concluded that they needed to say two to three positive things before bringing up a problem that would be viewed as negative. It worked for a while, and eventually enough trust was built to openly discuss problems.

Toyota’s persistence paid off—NUMMI became the best automotive plant in North America—comparable to Toyota’s plants in Japan on key performance indicators. And Toyota took what it learned and applied it to a successful launch of its own plant in Georgetown, Kentucky. Every plant, every sales office, every technical center was launched with a strong focus on building Toyota Way culture. It was not 100 percent though. Some Americans got it, others not so much. Developing Toyota culture was most successful in manufacturing and product development. But there was something distinctively Toyota-like in all parts of the company. Toyota’s experiences support the hypothesis that organizational culture can be sustained globally through persistent effort and learning. The best learning is direct one-on-one with a coach. Classroom training simply does not work to develop the right daily behavior.

Build a Deliberate Culture and Then Find People Who Fit

One of the big questions in the technical world is whether it is better to hire a competent person who can be developed to fit the culture or find the most talented individual star even if their personality is contrary to the culture. The individual star generally means great credentials—prestigious university, high grades, and fast tracker. We have observed many companies that go for the fast trackers and give them a quick pathway through different departments to get to a management position. According to a Harvard Business Review article on creative development work, star players can be up to six times as productive as others.7 So why not pay three or four times as much to get them?

It may not be a surprise to learn that Toyota in fact avoids star players, or at least people who think of themselves as stars. Toyota wants high performers, but its system is designed to develop people to be exceptional at what they do—some of course more exceptional than others. Toyota will always work to protect its system of human resource development and promotion and avoid people who are individualistic. It wants coachable team players who are excited to get their hands dirty and learn. For example, the company routinely passes over engineers from top universities, who have strong egos and ambition to fast track, often in favor of those from lesser-known engineering schools who have a clear passion for automobiles. One vice president had a favorite interview question: “If you could afford any car, what would you buy and why?” Someone who would talk excitedly about his childhood dream car and describe buying an old model and personally rebuilding it scored a lot of points.

Menlo also is obsessive about its culture of “Menlonians” and refuses to even do one-on-one interviews. Résumés are not terribly important—they show you have a pulse and have done well in academic courses. Richard Sheridan likes to say, “An interview is two people lying to each other.” It is more difficult to pretend to be something you are not when you are in an actual work situation, particularly when there is some stress involved. So Menlo interviews groups of people at once and gives them a variety of timed tasks. Since Menlo expects everyone to work in pairs all the time, the exercises are done in pairs. The person who grabs a pencil away from his partner or dominates the pair is not likely to be invited back. Those invited back then return to spend a day doing paid work paired with a Menlonian, and if they survive that, they are paid for several weeks and pair with several people. There is intense discussion about each potential employee by all those who worked with the person, and through a form of consensus final decisions are made.

One thing Menlonians fear with a passion is “towers of knowledge.” A tower of knowledge comes about when a brilliant software programmer is the only one who knows how a particular piece of software works. You coddle the person, hire the secret service to provide protection, insure them through Lloyd’s of London, and sweat at their every cough. The project will crash and burn without that programmer. Menlo does not want to be dependent on any one individual. Teamwork is the name of the game at Menlo. Enter its office and look around, and teamwork is in the air (see Figure 7.4).

Figure 7.4 Enter and see and feel teamwork

What you are actually seeing are pairs of people working together, enthusiastically (see Figure 7.5). They are sharing their knowledge. Richard talks of kindergarten rules. Be nice to your neighbors. Help them when you can. Oneupmanship is unacceptable. In fact, in what Menlo calls the “extreme selection process,” interviewees are told they will be judged by how good they make their partner (competitor) look. People rotate every single week. Of course, if there are people with a lot of experience, they will tend to rotate within the project, and an experienced person in the latest version of Java may be paired with someone with little Java experience. Teach each other. Learn together. Avoid towers of knowledge.

Figure 7.5 Working in pairs multiplies creativity, error detection, joy

Working in pairs is exhilarating, and there is joy in accomplishment. Finish a story card, and you have a sense of accomplishment. Get a green sticker from the quality advocates, and there’s a buzz. But get the customer to come in week by week and use your program flawlessly or give useful feedback, and that is priceless. On the other hand, for some people pairing is their worst nightmare, and they prefer to work alone. So be it. They have their choice of the vast majority of other IT firms in the world that are not Menlo. We have seen other companies with individualistic cultures that try to adopt paired programming—it rarely works.

One way Menlo’s culture caters to the common values of software programmers is its approach to meetings. Meetings can be distractions from the joy of accomplishment, so they are kept short at Menlo. Every day there is an all-employee meeting, but it is not a bunch of people packing a conference room and competing for the good chair, coffee and doughnuts in hand. It is a stand-up meeting in a huge circle—70 people holding a meeting (see Figure 7.6). Two people report out at a time, each holding a horn of the infamous Viking helmet that Rich and his wife, Carol, brought back from a trip to Norway. It became a symbol of collaboration and it is fun. Those holding it have the floor and report out. The helmet circulates around the circle. Everyone gets to speak, in pairs. Others chime in if they have something to offer. And the meeting is short and ends on time—usually 12 to 15 minutes after it starts. As visitors to Menlo have experienced, buying lots of Viking helmets will not reproduce Menlo’s culture. It is deep in the hearts and minds of Menlonians.

Figure 7.6 All-company meeting: the Viking helmet is the tip of the iceberg of shared culture

Is Toyota’s culture Japanese and oppressive? Is it unfair of Menlo to expect all members to conform to its apparently loose culture, which in reality is loaded with strict role expectations and codes of conduct? Rich Sheridan says he and his partners created a “deliberate culture.” They had a vision, and they are continually working toward that vision. A deliberate culture will almost by definition feel oppressive to people who do not fit in. Those who do not belong, but manage to slip through the selection filters, will feel alienated and will often complain . . . until they leave. When this happens, the culture is functioning as intended. If you want service excellence, do not compromise your deliberate culture that is working to fulfill its purpose in order to accommodate everyone’s personal vision of a desired culture. Find people who fit and then socialize them into the culture.

Of course, not all organizations have the luxury of renewing themselves through hiring. What do you do if you already have entrenched employees who do not fit the culture the organization decides it wants to change to? Then you have to work to socialize them into the new culture and develop them, which is the subject of Chapter 8. What you will notice is that some will develop faster and farther than others. Those are the ones you want to promote. Selection does not end at hiring, but rather it continues as people are developed and promoted, or not.

PRINCIPLE 12: INTEGRATE OUTSIDE PARTNERS

As open systems, all organizations must continually work with outside organizations whether they be customers, suppliers, government organizations, joint venture partners—the list goes on. Toyota is famous for its tight-knit supplier network tied together in a just-in-time system, but Toyota treats all key environmental actors as partners important to the success of the enterprise. In The Toyota Way I wrote of the company’s relationship with a lawyer who relearned how he practiced law based on the way Toyota worked with him and taught him. It was transformative. He learned to study the details of the case at a level beyond anything he had done in law school, question his every assumption, and work to collaborate even with hostile accusers. Service excellence depends on the performance of all people connected to the company to do their part at a high level of excellence and to fit the company’s processes and even culture.

Toyota’s Supplier Partnership Model

The Japanese keiretsu, a closely knit network of businesses that operate under an umbrella company, has received a great deal of attention in the popular press and management literature. There is a certain fascination with collections of companies that work together, selling shares to each other, meeting regularly to plot strategy, and doing a degree of exclusive business together. To some, it sounds like some sort of closed club colluding to take down the competition.

Over time the formal keiretsu were broken apart in the name of antitrust, with reductions in cross-ownership. Yet networks of companies that work with each other, or act under a broad umbrella like Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and the Toyota Group, continue to exist. Antitrust seems like an odd designation for the Toyota group since they are a collection of different companies—vehicle design and assembly, components manufacture, a trading company, a finance company—rather than a merger of competitors.

Ford, Chrysler, and General Motors all had large internal component groups, which in fact they spun off as separate companies when it became clear there were benefits to purchasing from outside suppliers competing with each other. Ford begat Visteon. General Motors begat Delphi. In a sense they were following the Japanese model of having a small number of outside suppliers in competition for their business. But the American companies did not know how to partner. And these internal component groups had high costs and lacked the skills to compete. Both these spin-offs ultimately went through Chapter 11 reorganization under bankruptcy law. This opened up competition, which reduced cost and put pressure on component suppliers for higher quality and service. But it was intense pressure from the customer organization, not collaboration, that drove cost reductions and quality improvement.

Decades ago, Toyota spun off its electronics department into Denso, which has grown to become the second largest global components supplier, selling to many non-Toyota companies. But Toyota has maintained a close relationship including some ownership and executives who leave Toyota to help lead Denso. Why maintain this tie to a longstanding partner? There are a variety of reasons, but at least one is the vision of an integrated enterprise with compatible cultures.

Denso fought for its independence to grow its non-Toyota business, but despite this, over time Toyota’s and Denso’s culture have become similar. Both believe in respect for people and continuous improvement. Both have invested heavily in lean systems in manufacturing. Both are obsessive at meeting new challenges through innovative products. Denso, like all suppliers who design components to fit Toyota vehicles, has many “guest engineers” who spend several years housed in Toyota R&D working side by side with Toyota engineers. This is obviously helpful for knowing what components Toyota will want in future vehicles, but it also leads to excellent communication and coordination between Toyota and its suppliers. They are building a compatible culture.

There are many ways that Toyota and its direct suppliers are integrated.8 There are supplier associations with regular meetings, annual themes of topics to focus on improving, and committees to work on special projects. Purchasing is much more than buyers who negotiate on price. The purchasing departments have many people skilled in TPS and quality who teach the suppliers—and bring ideas back to Toyota. Since first-tier suppliers are delivering just in time, with very little inventory, any issue that might threaten production becomes immediately visible and leads to intense discussion about why it occurred.

It is very difficult to become a Toyota supplier. Toyota’s general policy is to have two to three suppliers for a commodity in a region, for example seats in the United States, and they are locked in intense competition. When Toyota has this, there are no openings for additional suppliers. When Toyota moves into a new region or when there are new items to purchase because of technological innovation, the company starts by giving small contracts to a supplier. Over years, if the supplier proves itself, it will get more contracts until at some point it is part of the Toyota extended enterprise, and then it is difficult to get fired. However, it will have to compete and intensely improve quality, cost, and delivery. If it does not improve, it may lose a portion of its business to the competitor suppliers until it shows improvement. For those who get into the supply chain and perform, it is a stable and profitable business. They become partners and enjoy success with Toyota and go through bad times with Toyota, though generally Toyota’s lows are not as low as those of the rest of the industry. They increasingly learn over time respect for people and continuous improvement through Toyota’s tutelage and experience.

Toyota’s Call Center and Its Partners Were Vital in the Recall Crisis

The recall crisis of 2009 to 2010 was a major blow to Toyota’s self-image as a highly reliable automaker that always puts the customer first. We detailed what happened in Toyota Under Fire, and there was more speculation than facts about electronics problems causing sudden unintended acceleration. In fact, the U.S. National Institute of Highway Safety hired NASA, which did all it could to make Toyota vehicles fail, bombarding them with electromagnetic interference, and concluded there was no evidence the phenomena existed. Virtually every case of vehicles careening out of control where there was real data showed it was because of driver misapplication of the pedals. In other words, the driver pushed hard on the gas pedal when he or she intended to brake. Nonetheless, the media had a field day, and Toyota’s reputation was gravely in question. To Toyota it was a major crisis, and it wants to be sure the pain continues to motivate learning.

What was not visible to outsiders is that the first line of defense when a company like Toyota is publicly accused of potentially deadly safety problems is addressing the concerns of the anxious customer calling the company help line. When it was announced that Toyota would stop selling vehicles because of “sticky pedals,” the call volume went overnight from 3,000 calls per day to 96,000 calls per day. Call center personnel were dealing with anxious customers questioning whether they could safely drive their vehicles.

As Nancy Fein, then vice president of Customer Relations, described, calling it a difficult situation to manage through is an understatement:9

It was a very tough time with our customers, because our customers had periods where they didn’t trust us, or they felt like we were lying to them, or they felt that we were misrepresenting ourselves. Being in customer relations, that means that we had a really difficult role of not just taking care of an individual customer problem with the vehicle, but needing to rebuild our customers’ trust. We needed to fix our customers’ problems, and we needed to help them have belief, and have confidence in Toyota, the way we have confidence in Toyota.

Toyota had one big advantage in dealing with this crisis compared with many other organizations. It had decided many years ago to invest in its own call center rather than outsource it to low-wage countries. The careful selection and intense training of customer service representatives (CSRs) also made a huge difference. The employees in the call center at Toyota Motor Sales have been specifically screened for skills in building relationships with customers over the phone. While this is an entry-level job, it is not an easy job to obtain. Those who have the basic skill set go through a 4-week training course, followed by 6 to 18 months of close supervision before “graduating” as a full-fledged CSR.

Each of the Toyota CSRs is empowered to make decisions on the spot to help resolve customer issues. In addition to being directly connected to dealer service centers, a CSR working through the recall crisis could also immediately approve such expenses as having a car towed to the dealer, reimbursing a customer for renting a car or arranging a loaner vehicle from a dealer, or extending a warranty to cover other issues that a customer might be having. Once a customer talks to a CSR, an attempt is made to connect that customer to the same CSR on any follow-up phone calls. For every five CSRs, there is a supervisor who monitors selected calls, coaches the CSRs, and can authorize more expensive solutions.

Another somewhat unique feature of the TMS call center was the use of quality circles, even during the height of the crisis. Every call center supervisor had a quality circle of 8 to 10 CSRs, meeting once a week to talk about problems, solutions, and best practices. These quality circles were led by senior CSRs as a way of giving them experience in leading quality circles and of continuing to ramp up the skills and training of the outside personnel.

A second critical advantage Toyota had is the close partnerships it had fostered with trusted subcontractors whom Toyota developed almost as if they were inside employees. Over the years, Fein had built long-term relationships with three call center staffing agencies that had trained personnel on hand. By the end of the first week, all three of the agencies were providing supplementary staff to the call center. These supplementary staff had already had training as customer service representatives, but they still underwent up to three days of specific training to prepare them to handle the often emotional calls during the recall crisis. As well, the outside agency personnel were integrated to a degree into the Toyota processes. Group leaders listened in on random calls to coach the subcontractors, as they did with regular employees. The outside contractors were even invited to participate in the quality circles to help resolve issues that arose and develop their problem-solving skills.

Still, in order to ensure the highest quality of service, TMS had the CSRs from the outside agencies primarily deal with information requests, such as a customer calling in with his Vehicle Identification Number to confirm whether his vehicle was or was not part of the recall. If a customer had more serious questions or believed that he had experienced sudden acceleration or a sticky pedal, the outside agencies were able to transfer a call to the TMS call center immediately, so that the more experienced Toyota CSRs could work with the customer.

One measure of the effectiveness of this group was in customer satisfaction. To Toyota’s surprise the customer satisfaction of those whose cars were recalled was even higher than those whose cars were not recalled. Apparently the additional attention they received from the highly skilled CSRs, as well as very accommodating dealerships that went out of their way to address customer concerns, increased customer satisfaction.

The Risks of Outsourcing Services

It has become fashionable to outsource services—bundle together services into centralized “shared resources” and then contract them out. Outsource human resource services, IT services, call centers, and anything else that leads to a reduced cost per piece. There are short-term savings, and it is certainly attractive. Often new CEOs of service organizations use outsourcing as one of their strategies to turn around the company. But there is a risk!

Unlike Toyota, which carefully sifts through opportunities and experiments on a small scale, gradually developing suppliers up to Toyota standards, most service organizations seem to treat outsourcing as though they are holding an auction. Who will be the lowest bidder? We saw what happened in Chapter 6 when a healthcare system centralized laundry services in a highly automated system. It was a whiz-bang impressive system that simply could not clean enough laundry to keep the hospitals running.

As much of an investment as we need to make in people and processes inside the firm, we need a similar effort outside the firm. The process of improvement is fractal. The same thinking and systems are needed at every level, inside and outside the firm. We have seen companies take years to develop their own lean cultures, only to expect suppliers to change through a few one-week lean workshops. It simply will not happen.

This is why Toyota will first build its own internal competency and then gradually outsource until it can build highly reliable outside capability that it can rely on as if the supplier were integrated into the culture. We saw that Toyota invested heavily in its own internal call center and then partnered with and developed outside services for additional capacity in peak periods.

This is not to say that Toyota invests heavily in developing every supplier of nuts and bolts and safety gloves. Before outsourcing to the relatively low bidder that has an acceptable quality record, consider: Is it truly a commodity where one quality service provider is as good as another and location does not matter? What are the coordination requirements? How much customization is needed? Consider the service typology from Chapter 1 (Figure 1.10). In general, suppliers of standard services are more likely to provide commodities that can be outsourced at arm’s length compared with suppliers of customized services that need to be closely integrated into your company culture. The outside call centers used by Toyota were providing something between a standard experience and a personalized one. Mostly Toyota sent them customers with standard questions, though the crisis heightened the need for a personal touch for all customers.

Integrating Customers into the Culture at Menlo

Menlo truly operates as an open system. For example, Menlo gives hundreds of tours each year involving thousands of people. Customers regularly come to plan the project or attend “show-and-tells.” Classes are held to teach Menlo’s system to other companies. Even babies and dogs are welcome. Human interaction is visible everywhere all the time. Toyota also openly shares its system through daily tours of selected plants. People often ask, “What’s in it for Toyota to openly share what it does?” There are many answers, but one looms above the rest. Opening yourself up to outside visits, and scrutiny, can strengthen your culture.

As noted earlier, Richard Sheridan’s job title is chief storyteller. This seems like a cute joke, but he is serious. His biggest asset to the company is telling stories. Externally his book and presentations help sell the IT work and the training business that Menlo does. But what Menlo is selling is its culture. And stories are part of the lifeblood of culture. Stories help us create a collective identity. Hearing our stories repeatedly told to outsiders helps reinforce our culture. Having a constant stream of visitors motivates us to sustain our culture, including keeping artifacts up-to-date and visible. Being open to outsiders at Menlo both rejuvenates the culture that is Menlo’s chief asset and rejuvenates customers who find joy in being part of the community.

Customers cannot help but be integrated into the Menlo process and culture. They are part of the Menlo team from selecting the primary and secondary user personas that we described in Chapter 5 to selecting the story cards they are willing to pay for week by week, to show-and-tells to review the software week by week. The customers are often IT folks who come from a more traditional culture. They do not use folksy language like “show-and-tell” meetings; they do not make critical quality decisions with colored sticky dots; they do not use dart board images to select key users. Menlo is an energizing and fun environment, and often customers do not want to leave. One IT manager who cannot bring his dog to work because of legitimate hygiene concerns in a closely controlled environment asked to bring his dog to Menlo, and the answer was “Certainly.” He wears jeans to meetings on Menlo days. He is relaxed yet energized at Menlo. Sometimes he asks if he can continue to hang out and do his work at Menlo after the meeting. For some period of time he is part of the Menlo culture.

The weekly show-and-tell is critical both for getting rapid feedback and for engaging customers with the culture. Each week the customer comes to Menlo, is handed the story cards coded that week, and is asked to operate the system with the newly programmed features (see Figure 7.7). The customer is in control. She is not given voluminous instruction manuals. If the software is not intuitive, it needs improvement. In systems theory we learn that the speed of feedback is critical to self-correcting loops. PDCA depends on rapid feedback and equally rapid responses to the feedback. Week by week the software is written, tests are written to check the software technically (does it do what it is supposed to), and quality advocates check to see if the software meets their understanding of what the customer wants. But the customer is the final check. By the last week of a three-year project, all that is really being checked is the last week of work. Is it a wonder that the customer will take the final software and often use it for real work the same day it arrives, flawlessly? Customer complaints are an ancient relic of a past life.

Figure 7.7 Customer show-and-tell

An even more direct way that Menlo integrates its customers into the business is through equity ownership. When Menlo contracts with new clients for work, the company offers to accept half the bill in equity in the company. Menlo figures if it is truly committed to helping clients, and believes its software will make them better, then it should put its money where its mouth is.

One of the pioneering efforts, which turned out to pay off handsomely, was taking equity in a start-up firm that developed the Accuri flow cytometer. Flow cytometers are used to analyze cells in both research and clinical settings for cancer, AIDS, leukemia, and various other immunological disorders. Jen Baird and Colin Rich were two Ann Arbor entrepreneurs with an idea. They had licensed their technology out of the University of Michigan Office of Technology Transfer, and their intention was to revolutionize the world of flow cytometry by creating an affordable, easy-to-use, and very compact personal flow cytometer. This type of product had been on the market for 30 years, but the existing products were big, cumbersome, difficult-to-use maintenance nightmares and very expensive.

One thing the people at Menlo had learned early on was that they had to teach their process to their clients. At the outset of the project, Accuri was asked to attend a full-day class in the Menlo process so it could learn what to expect and what role it would play in the project’s success. In this case it was more of a joint development project than a separable software task—the hardware and software were being developed in parallel.

Menlo taught Accuri about the various failure modes of development projects, software or otherwise, and how Menlo’s process avoided those failures. I interviewed Richard about this experience, and he explained the failure modes and Menlo’s countermeasures:

1. Projects often get off track, and no one realizes it until it is too late. Our solution was a weekly Show & Tell where Jen and her team could try out the emerging software to witness firsthand the tangible progress. This grounded the progress report in reality rather than typical status reports, Gantt Charts and percent completion statistics which are impossible to verify in a software project.

2. Failure often occurs because budgets are not well tracked and money runs out when the project is “80 percent complete” and unshippable. Our iterative and incremental approach meant we always had working software that could be shipped, if needed, even if all the features weren’t present.

3. Projects often technically succeed, but end up unusable by the target audience and thus fail to achieve the widespread adoption necessary for a profitable business. We taught Jen and her team about our High-Tech Anthropology approach to user experience design. We would ask them to introduce us to real end users who were already using existing flow cytometers from their competitors. Our High-Tech Anthropologists would study these users in their native work environments to understand their struggles and design those struggles out of the user experience. Our goal was to produce software that did not need user manuals, training classes or help text and could be used immediately by the typical end user.

4. A very typical failure mode of software products is their overly ambitious goals to be “all things to all people.” We combat this through the use of personas and persona maps which prioritize the types of user so that we have exactly ONE primary type of user we are trying to serve better than anyone else. They chose an inexperienced graduate assistant who currently is not allowed to use the existing flow cytometers because the error rates were too high and thus only lab directors would use the current products in the market. While this choice may seem unusual at first, there were 10 graduate assistants to every lab director and thus, if we succeeded in addressing this audience the target market would be larger by an order of magnitude. It was a bold move.

5. Even if all this goes well, software quality can still suffer and the product fail due to unreliability. This is often manifested in the later stages of a product development effort when time and budget are being exhausted and an overworked team puts the pedal to the metal and starts working tons of overtime including weekends, all-nighters and delayed or cancelled vacations. Many, many bugs are introduced at this stage due to fatigue, and it is often impossible to overcome this onslaught of quality issues after the product is released, as first impressions can doom a new product if it continually crashes or creates errors. We had to teach the Accuri management team about our paired-programming approach and our hard rule of no more than 40-hour work weeks, our automated unit testing practice, and the consequent positive effect all of this would have on the final product.

One other problem emerged quickly. Phase one of the project as defined by the project leader Jen was estimated to cost $600K, and she only had $300K to spend on her software team. As good as everything felt to Jen and her team, the reality was they could not afford us. I suggested we cut our cash price in half and trade the rest for equity. Jen was shocked that an outside vendor would be willing to place that big a bet on a start-up client. I confirmed for her once again our relational model and said if we were not willing to bet on the outcome, we shouldn’t do the project in the first place. The deal was done and we began work. Throughout the nearly three and a half years of product development we continued to trade cash for equity as we had in that first project. We also struck a deal to trade cash for a future royalty on the product once it shipped. We were all in.

The first unit shipped after 3½ years, and it worked beautifully right out of the box. That first customer was able to plug it in and start using it without user manuals, help text, or training classes, just as Menlo had predicted. Orders began to flow in. Within three years after the first unit shipped, Accuri had captured nearly 30 percent of the worldwide market in flow cytometry, and the company was purchased by one of its largest rivals for $205 million. Menlo made millions, the Accuri founders got rich, and everyone was happy, especially the users who now had a flow cytometer they loved to use.

START WITH MACRODESIGN OR BUILD CULTURE PERSON BY PERSON?

This is a difficult question to answer in generic terms, as it is very organizationally specific. New CEOs brought in from the outside to turn around the company will typically spend a good deal of time with their close inner circle redesigning the organizational structure and envisioning the new culture—which not surprisingly will often resemble where they came from. They pore over boxes on charts. “We are organized by region, but we should be organized by product group with profit and loss responsibility.” “The product organization has become so cumbersome we need to refocus it with four major groups instead of twelve and build in strong financial and marketing functions.” “The organization has emptied out the corporate office, and running this organization is like herding cats—we need to strengthen the corporate office and all work for one company.” If the organizational design is A, the new CEO will shift to B or C.

The culture is even more amorphous. “I have interviewed dozens of people, and my conclusion is that we have a broken culture.” “This is an ‘I’ culture. We need a ‘we’ culture.” “This is a culture of ‘it’s not my job.’ We need a culture of ‘accountability.’”

Perhaps these CEOs are correct that there needs to be some realignment of priorities and even stronger shared values, but how will they achieve this? In command and control organizations the CEO is putting in place levers to control profits—higher sales and lower costs. Where can the CEO create the highest leverage points for results? Develop new service offerings, business models, promotions, advertising? Eliminate low performers—services and the people associated with them? If there are different groups of people in different parts of the organization responsible for a similar service offering, then organizing shared services in one unit can allow for head count reduction, consolidation, or outsourcing. And someone at the helm of each service unit becomes the go-to person to squeeze for results—sink or swim—and by the way find his own lieutenants to squeeze, and so it goes on down the line until we have a culture of “accountability.” “Get results or else” becomes the unofficial mantra of the new culture.

Contrast this with what Elisa’s CEO did. At Elisa he asked, “How can we create core customer-facing units where we can have the maximum leverage on customer satisfaction?” It was clear he was interested in accountability. But his was accountability to the customer. Get someone in charge who can be the first to be coached on how to solve the customer’s problems—one by one. Eliminate those nasty billing errors that cause angst. Get the service outages fixed fast and find the root cause so they do not come back. Elisa then enjoyed a rapid rise in customer satisfaction. But the folks at Elisa were not done. They had just begun. After spending over five years developing people at the local level and defining core processes to get end-to-end value streams focused on customer satisfaction, the people at Elisa turned their focus to continuous improvement, and so every day in 2014–2015 they worked on the core values of the company. The goal was to develop a picture of their target culture. Ranta-aho Merja, executive vice president of Human Resources, led the effort and explains:

We engaged our whole personnel in dialogue about what we feel is important to us. We integrated our excellence principles into our core values, that now contain five distinct values, each being explained by three behaviors that we want to cherish and develop. We find that the only way to reach excellence is to consciously build a culture that supports passion for the customer, continuous learning and improvement, and mutual respect.

In the meantime, Petri was focused on creating daily management systems so small groups of frontline supervisors and their team were solving problems every day. Petri then was put in charge of sales to bring the daily management system to the sales organization with great success. The macrolevel context had set the stage for the hard work of building a culture of continuous improvement.

In our experience a culture based on quick results, fear, and generous rewards for a few can be rapidly established, though it lacks depth beyond the executive suite and a few senior levels of management. A culture of service excellence is slow to build, takes constant vigilance to sustain, but is the only true path to greatness.

KEY POINTS

MACROLEVEL PEOPLE PRINCIPLES

1. Organizational design is particularly important in services because, unlike manufacturing, there aren’t clear boundaries for making things.

![]() Macrolevel people processes create a context for people to understand where they fit into the organization and “find their way.”

Macrolevel people processes create a context for people to understand where they fit into the organization and “find their way.”

2. Organizing to balance deep expertise and customer focus allows the organization to be flexible to the changing needs of customers:

![]() Common types of organizational design include functional organization, customer-facing organization, matrix organization, and networked organization.

Common types of organizational design include functional organization, customer-facing organization, matrix organization, and networked organization.

![]() Over time, organizational design can—and should—change, based on changes in the environment, including markets, and an ever-deepening understanding of the needs of customers and the business.

Over time, organizational design can—and should—change, based on changes in the environment, including markets, and an ever-deepening understanding of the needs of customers and the business.

3. Culture is extremely complex, and each organization’s culture develops over time; culture can just “happen,” or it can be cultivated deliberately so that every person understands the nuances of the culture and how to act in accordance with the culture, whatever the person’s role:

![]() Creating a deliberate culture means hiring deliberately: carefully interview and screen for cultural fit during the hiring process.

Creating a deliberate culture means hiring deliberately: carefully interview and screen for cultural fit during the hiring process.

![]() Make sure that the hiring process itself reflects the culture of the organization.

Make sure that the hiring process itself reflects the culture of the organization.

![]() Creating a deliberate culture means making sure that all key aspects of the culture and expectations are understood and practiced in all functions.

Creating a deliberate culture means making sure that all key aspects of the culture and expectations are understood and practiced in all functions.

4. Integrate outside partners (suppliers and customers) into your organization’s culture deliberately since suppliers’ services and products will ultimately touch and affect your customers, and customers should be providing continual feedback about their needs.

5. Building a deliberate culture of service excellence will take time, effort, and a deep understanding of your customers’ needs and your organization’s purpose.