CHAPTER 3

Organizing the Production

Before somebody laughs at the idea, remember that concepts like an all-news network, a food channel, and a weather channel were thought to be fallacies at the conception stage. All have developed into unquestioned broadcasting successes over the years.

Tim Griffin, Writer

A lot of what is covered in this chapter is obvious—so obvious that many production people overlook these essentials in their initial enthusiasm—and their product is less effective.

Key Terms

■ Arc: A camera move that moves around the subject in a circle, arc, or “horseshoe” path.

■ Empirical production method: The empirical method is where instinct and opportunity are the guides.

■ Goals: Broad concepts of what you want to accomplish with the program.

■ Multicamera production: When two or more cameras are used to create a television production. Usually a production switcher switches the cameras.

■ Objectives: Objectives are measurable goals. That means something that can be tested for, to see that the audience did understand and remember the key points of the program.

■ Planned production method: The planned method, which organizes and builds a program in carefully arranged steps.

■ Remote survey (Recce): A preliminary visit to a shooting location.

■ Shot sheet (shot card): A sheet created by the director that lists each shot needed from each individual camera operator. The shots are listed in order so that the camera operator can move from shot to shot with little direction from the director.

■ Single-camera production: Single-camera production is when one camera is used to shoot the entire segment or show.

■ Site survey: See “remote survey.”

■ Storyboard: The storyboard is simply a series of rough sketches that help you to visualize and to organize your camera treatment.

3.1 ART CONCEALS CRAFT

When watching a show on television, our thoughts normally center on the program material: the story line, the message, and the argument. We become interested in what people are saying, what they are doing, what they look like, and where they are. Unless we start to get bored or the technology becomes obtrusive, we are unlikely to concern ourselves with how the production is actually made.

We believe what we see. We respond to techniques but remain unaware of them unless they happen to distract us. We even accept the drama of the hero dying of thirst in the desert without wondering why the director, camera, and sound crew do not help him.

All this is fine until you begin to make programs yourself. You soon realize the gulf between watching and enjoying from the audience’s point of view, and creating the illusion by the way the equipment is used (Figure 3.1).

3.2 SHOT SELECTION

You cannot just point a camera at a scene and expect it to convey all the information and atmosphere that the on-the-spot observer would experience. A camera is inherently selective. It can only show certain limited aspects of a situation at any given time. If, for instance, you provide a wide shot (WS) of the entire field at a ball game, the audience will have an excellent view of the movement patterns of teamwork, but the viewers will be unable to see for themselves who individuals are or to watch exactly how they are playing the game. A close-up shot (CU) gives details, even shows how a player is reacting to a foul, but prevents the audience from seeing the overall action at that time (Figure 3.2).

FIGURE 3.1

Beginning directors often find that the illusion of reality is

much more difficult to create than they first imagined.

FIGURE 3.2

Shot selection at a baseball game determines whether you are showing the teamwork with a long shot or the emotions with an extreme close-up shot.

3.3 THE PROBLEM OF FAMILIARITY

There is an essential difference between the way any director looks at the program and how the audience reacts. That is not surprising when you stop to think about it. The director is completely familiar with the production and the circumstances in which it has been prepared. For example, let’s say that the program is showing us a collection of priceless objects in a museum. There can be significant differences between the reactions of a viewer seeing the program for the first time and the director’s own reactions:

From the audience’s point of view:

There were some unusual items in the display case, but the camera continued past them. Why didn’t we have a closer look at the decorated plate so that we could read the inscriptions? There seems to be elaborate ornamentation on the other side of this vase. But we don’t see it. Why isn’t it shown? Why aren’t we looking at all the interesting things there in the background?

The director’s view:

The camera picked out the most important details for the topic we were discussing. There isn’t time to cover everything. When shooting the vase, this was the best viewpoint we could manage. The voiceover read the inscription to us. Nearby display cases prevented a better camera position. The museum was about to close, and we were scheduled to be elsewhere the next day.

This imaginary discourse reminds us of several important points. First, there are many ways of interpreting any situation. A good director will give the subject a great deal of thought before shooting and will rationalize how best to tackle the shoot. But most productions are a matter of compromise between aesthetics and mechanics, between “what we would like to do” and “what we are able to do.” Quite often, the obvious thing to do is quite impractical for some reason (it is too costly, there is insufficient time, it requires equipment beyond what is available, the light is failing, etc.). During the production you will often discover great on-the-spot opportunities that you did not anticipate. However, you will also encounter frustrating disappointments that will require you to rethink your original plans.

Directors spend a considerable amount of time on a project and become very familiar with each facet of the production as well as the locations. Members of the audience, on the other hand, are continually finding out what the program is about; they are interpreting each shot as they see it, often with only a moment or two to respond to whatever catches their attention.

The director was not only there at the shoot but has probably seen each shot on the screen many times: when reviewing the takes, during postproduction sessions, and when assessing the final program. He or she knows what material was available and what was cut. The audience members are seeing and hearing everything for the first and probably the only time. They do not know what might have been. They cannot assess opportunities missed. For them, everything is a fresh impression.

The audience only sees as much of a situation as the camera reveals, quite unaware of things that are just a short distance outside the lens’s field of view— unless something happens to move into the shot, or the camera’s viewpoint changes, or there is a revealing if unexplained noise from somewhere out of shot (Figure 3.3). When the camera presents us with impressive shots of a world-famous scene, it may carefully avoid including crowding tourists, stalls selling souvenirs, or a waiting bus. A carefully angled shot of a scene can produce a powerful effect on screen but a disappointing reaction when one stands on the specific spot and sees its true scale and its surroundings.

At times, the director is at a disadvantage. Because the director is familiar with every moment of the production, it is not possible for the director or the production team to judge with a fresh eye. It might seem to the director that a specific point is so obvious that only a very brief “reminder” shot is needed at the moment. He or she may decide to leave it out altogether. But for viewers who are watching the scene for the first time, this omission could prove puzzling. They may even misunderstand what is going on as a result.

To simplify the mechanics of production, scenes are often shot in the most convenient order, irrespective of where they come in the final script. This will all be sorted out during the editing process. While this arrangement can be a practical solution when shooting, it does have its drawbacks. Not only does shooting out of sequence create continuity problems, it can make it difficult for the director to judge the subtleties of timing, tempo, and pace that the viewer will experience when looking at the final program (Figure 3.4).

FIGURE 3.3

Overfamiliarity: The director knows how interesting the location is, but is it revealed to the audience? The director has to decide whether to show the context of the shot or a close-up. Directors have to determine which shot best communicates the story.

FIGURE 3.4

Shooting scenes out of sequence can create continuity, timing, and pace difficulties.

3.4 THE ISSUE OF QUALITY

When shooting pictures for pleasure, you can be philosophical if the odd shot happens to be slightly defocused, or lopsided, or cuts off part of the subject. It is a pity, but it doesn’t really matter much. You can still enjoy the results. But when you are creating a program for other people, any defects of this kind are unacceptable. They will give a production the reputation of carelessness, amateurishness, and incompetence so that it loses its appeal and authority. Faulty camerawork and poor techniques will not only distract your audience, but they can turn even a serious, well-thought-out production into a complete disaster.

3.5 “BIGGER AND BETTER”

“Bigger is better” does not necessarily translate into a better production. How you tackle any program is directly influenced by your resources (equipment, finance, crew and their experience, etc.), time, conditions, standards, intended market, and so on. Sometimes “bigger” may distract viewers from the real subject. If you choose to use special effects and all the viewer remembers is those special effects, then you have not communicated your message. The treatment must be appropriate for the target audience and the program content (Figure 3.5).

FIGURE 3.5

While shooting a scene underwater may be a really cool addition to the production, you have to determine if you can afford the equipment, have the staff that can shoot it well, and if it is really worth the expense for what you get.

(Photo by Sarah Hogencamp)

FIGURE 3.6

The stages that a video production goes through, from idea (concept) to the viewing.

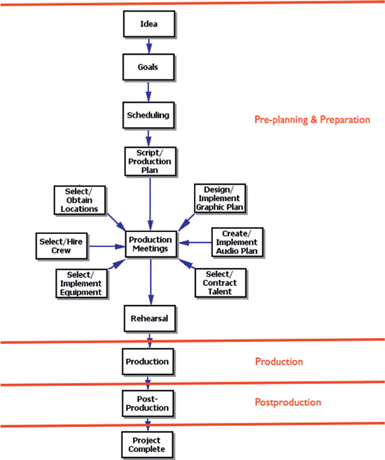

THE PRODUCTION PROCESS

3.6 IT ALL STARTS WITH AN IDEA (CONCEPT)

It is unlikely that you will suddenly decide, out of the blue, to make a video program on a specific subject. Perhaps you heard of an interesting incident that gave you the idea for a narrative. Maybe a local store asked you to make a point-of-sales video to help the home handyman. Here is how to start with the project:

You know the subject to be covered (in principle at least), what the program is to be used for, and who the audience for the program will be. The next question you should probably ask is “How long should it be?” It is important to know if the client wants a 2-hour epic or a 2-minute video loop.

Determine how the audience is going to relate to this program. If it is one of a series, don’t go over the same material again unless it requires revision. There is also the chance that the viewer may not see the other videos in the series (Figure 3.6).

3.7 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

Goals and objectives are a very important part of the production process. What do you really want your audience to know after they have viewed your production? The answer to this question is essential because it guides the entire production process. The goals and objectives will determine what is used as a measuring stick throughout the production process. Goals are broad concepts of what you want to accomplish:

Goal: I want to explain how to field a Formula One racing team.

Objectives are measurable goals. That means something that can be tested for to see that the audience did understand and remember the key points of the program. Take the time to think through what the audience should know after seeing your program:

Objectives: When the viewers finish watching the program, 50 percent of the audience should be able to:

■ identify three types of sponsorship;

■ identify four crew positions;

■ identify two scheduling issues.

All three of these are objectives because they are measurable. The number of objectives is determined by the goals. This means that sometimes only one objective is needed, while other times five may be required.

3.8 DETERMINING YOUR AUDIENCE

Whether your program is a video “family album” or a lecture on nuclear physics, it is essential to determine who your audience is. The following questions help you target your audience:

■ Who is the viewing audience?

■ Is it for the general public, for a specific group, or for a local group?

■ What is the target age group? Is the production for children, young adults, adults, or seniors? Some age groups, such as children, have many subsets as well such as preschool, grade school, middle school, and high school. Each subset must be communicated to in a different way.

■ Is any specific background, qualification, language, or group experience necessary for the audience?

■ Are there specific production styles that this audience favors?

The target audience should determine your program’s coverage and style. Obviously you create a program differently for a group of scientists from how you would for young children in a science class (Figure 3.7).

How and where your audience will view your program is important to know. Today, most video content is viewed online or downloaded to a computer or mobile phone. Directors try to anticipate the viewing conditions, since they can considerably affect the way the program is produced. Will the viewer be watching the program on their phone by themselves or will they be seated as part of a group watching a large screen in a darkened classroom or theater? Will they will be watching training videos being streamed off of the Internet while at the office (Figure 3.8)?

FIGURE 3.7

The intended audience should determine how the director covers the subject. In this situation, generally a younger crowd would favor a different style of coverage from elderly people.

(Photo by Paul Dupree)

FIGURE 3.8

With small mobile phone devices having the ability to play hours of video, as well as shoot video, they are rapidly becoming the video player of choice for many people.

If the program will be primarily viewed in direct daylight, directors may want to avoid dark or low-key scenes. The images displayed on many receivers/ monitors in daylight can be poor quality, although they are continually improving in quality.

Try to anticipate the problems for an audience watching a distant picture monitor. Long shots (LS) have correspondingly little impact. Closer shots are essential since they add emotion and drama. Small lettering means nothing on a small distant screen. To improve the visibility of titles, charts, maps, etc., keep details basic and limit the information (Figure 3.9).

If your target audience may be watching on a smart phone or other small video screen device, directors should lean toward more CUs than usual since the LS may not be as discernible on the small screen (Figure 3.10).

Here are a number of reminder questions that can help you to anticipate your audience’s problems:

■ What does your audience already know about the subject?

■ Does the program relate to other programs in a series? Does the audience need to be reminded of earlier programs?

■ Is the audience going to see the program individually or in a group?

■ Are they only watching the program once, from the beginning, or as a continuous loop?

FIGURE 3.9

Close-up shots add emotion and drama to a production and add needed detail to small-screen productions, such as those seen on a smart phone.

FIGURE 3.10

As viewing screens have become smaller, care must be taken to create videos that can be seen with clarity. Highly detailed scenes, as shown in this image, usually require the addition of more close-ups.

■ Can they see the program as often as they want, including stopping and replaying sections?

■ Will viewers watch the program straight through, or will it be stopped after sections, for discussion?

■ Will there be any accompanying supporting material (maps, graphs, or statistics) to which the audience can refer?

■ Will there be other competing, noisy attractions as they watch (such as might occur at an exhibition)?

■ Will the program soon be out of date?

■ Is the program for a formal occasion, or will a certain amount of careful humor be useful?

■ Are there time limits for the program?

3.9 RESEARCH

For some programs, such as documentaries, news, or interviews, the production team must conduct research in order to create the content or make sure the existing content is accurate. This research may be going to the library, doing online research, or contacting recognized experts in the content area. Travel may even be required. It is important to remember that research is time-consuming and may impact the production budget.

3.10 COVERING THE SUBJECT

The kind of subject that is being covered, who makes up the audience, and the content that needs to be featured will influence how the camera is utilized in the program, where it concentrates, how close the shots are, and how varied they are. Here are some of the areas that the director needs to think through:

FIGURE 3.11

Create shot sheets (shot card) or other support information for the camera operators as needed.

■ What content areas need to be covered?

■ Is the subject (person or object) best seen from specific angles?

■ Are the surroundings (context) important?

■ Would the addition of graphics help the audience understand the content?

■ Would it help to create a shot list for each camera operator? A shot list is a description of each shot needed, listed in order, so that the operator can move from shot to shot with little instruction from the director. Other camera operator supports may include team rosters to help the operator find a specific player for the director (Figure 3.11).

3.11 PRODUCTION METHODS

Great ideas are not enough. Ideas have to be worked out in realistic, practical terms. They have to be expressed as images and sounds. In the end, as the director, you have to decide what the camera is going to shoot and what your audience is going to hear. Where do you start?

There are two quite different methods of approaching video production:

■ The empirical method is where instinct and opportunity are the guides.

■ The planned method, which organizes and builds a program in carefully arranged steps.

3.12 THE EMPIRICAL APPROACH

Directors following the empirical approach get an idea, and then they look around for subjects and situations that relate to it. After shooting possible material, they later create a program from whatever they have found. Their inspiration springs from the opportunities that have arisen.

After accumulating a collection of interesting sequences (atmospheric shots, natural sound (NAT), interviews, etc.), the director reviews the content and puts it into a meaningful order. He or she then creates a program that fits the accumulated material, probably writing a commentary as a voiceover to match the edited pictures.

At best, this approach is fresh and uninhibited, improvises, makes use of the unexpected, avoids rigid discipline, and is adaptable. Shots are interestingly varied. The audience is kept alert, watching and interpreting the changing scenes.

At worst, the result of such shot hunting is a haphazard disaster, with little cohesion or sense of purpose. Because the approach is unsystematic, gaps and overlaps may occur. Good, coherent editing may be difficult. The director usually relies heavily on the voiceover to try to provide any sort of relationship and continuity between the images (Figure 3.12).

FIGURE 3.12

Some productions are shot using the empirical method, which is when instinct and opportunity are the guides.

3.13 THE PLANNED APPROACH

The planned method of production approaches the problem quite differently, although the results on the screen may be similar. In this situation, the director works out, in advance, the exact form he or she wants the program to take and then creates it accordingly.

Fundamentally, you can do either of the following:

■ begin with the environment or setting, and decide how the cameras can be positioned to get the most effective shots (Figure 3.13);

■ envision certain shots or effects you want to see, and create a setting that will provide those results.

FIGURE 3.13

Narrative directors use the planned approach to production by creating the setting to fit the story.

Usually the planned approach is a method in which the crew can be coordinated to give their best. There is a sense of systematic purpose throughout the project. Problems are largely ironed out before they develop. Production is based on what is feasible. The program can have a smooth-flowing, carefully thought-out, persuasive style.

At its worst, the planned approach production can become bogged down in organization. The program can be stiff, routine, and lack originality. Opportunities are ignored because they were not part of the original scheme and would modify it. The result could be a disaster.

In reality, the experienced director uses a combination of the planned and the empirical approaches, starting off with a plan and then taking advantage of any opportunities that become available.

3.14 STORYBOARDS

Storyboards generally save time on-set, help to avoid rushed decisions on-set, help you improve and get feedback on ideas, give you an idea about how many cameras and angles you will need, help you experiment with different angles and techniques, can help with continuity, and help orientate actors and crew members.

Kyle Van Tonder, Director

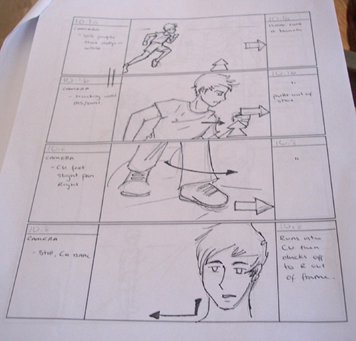

Before even picking up a camera, directors need to think through each scene in their minds so that they can then capture the best images that tell their story. The storyboard is simply a series of rough sketches; these sketches help the director to visualize and organize the camera treatment. Generally, the script, if you are using a script, is broken down into segments, and each segment is visualized on the storyboard—giving the director a visual interpretation of the script. The storyboard is a visual map of how the director hopes to arrange the camera shots for each scene or action sequence (Figures 3.14 and 3.15).

FIGURE 3.14

A storyboard on the set of a production. The storyboard roughly visualizes what the program will look like.

(Photo by Taylor Vinson)

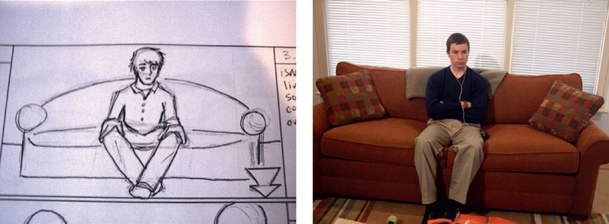

FIGURE 3.15

The first image is of a frame from a storyboard. The second image shows how the camera shot that specific scene.

(Photo by Taylor Vinson)

Storyboards can be designed a number of different ways. There are software programs that assist the director in visualizing ideas; someone can roughly sketch them out, or a storyboard artist can create detailed drawings that can even be animated to show during the fund-raising period. You don’t have to be able to draw well to produce a successful storyboard. Even the crudest scribbles can help you organize your thoughts and show other people what you are trying to do (Figures 3.16 and 3.17).

Whether you choose a storyboarding software or drawing it by hand, you begin by imagining your way through the script, roughly creating the composition for each shot. If the action is complicated, you might need a couple of frames to show how a shot develops. In our example, the whole scene is summarized in five frames.

FIGURE 3.16

Storyboard programs are available on all types of devices. Both of these screenshots were taken from a storyboard program on an iPhone.

(Software by Cinemek)

FIGURE 3.17

Computer-based storyboard programs allow the nonartist to create professional-looking storyboards.

(Software by StoryBoard Quick)

Let’s look at a simple story line to see how the storyboard provides you with imaginative opportunities (see the storyboard sidebar “Analyzing Action”).

The young person has been sent to buy her first postage stamp.

There are dozens of ways to shoot this brief sequence. You could simply follow her all the way from her home, watching as she crosses the road, enters the post office, goes up to the counter. The result would be totally boring.

Let’s think again. We know from the previous scene where she is going and why. All we really want to register are her reactions as she buys the stamp. So let’s cut out all the extra footage and concentrate on that moment:

1. The child arrives at the counter, and looks up at the clerk.

2. Hesitatingly, she asks for the stamp.

3. She opens her fingers to hand the money to the clerk.

4. The clerk smiles, takes the money, and pulls out the stamp book.

5. A close shot of the clerk tearing the stamp from a sheet (Figure 3.18).

You now have a sequence of shots, far more interesting than a continuous “follow-shot.” It stimulates the imagination. It guides the audience’s thought processes. It has a greater overall impact. However, if this type of treatment is carried out badly, the effect can look disjointed, contrived, and posed. It is essential that the treatment matches the style and theme of the subject.

You could have built the whole sequence with dramatic camera angles, strong music, and effects. But would it have been appropriate? If the audience knows that a bomb is ticking away in a parcel beneath the counter, it might have been. It is all too easy to overdramatize or “pretty up” a situation (such as star filters and diffusion filters for misty effects). Postproduction is where most special effects can be added as needed.

This breakdown has not only helped you to visualize the picture treatment, but you begin to think about how one shot is going to lead into the next. You start to deal with practicalities. You see, for example, that shots 1 and 3 are taken from the front of the counter, and shots 2, 4, and 5 need to be taken from behind it. Obviously, the most logical approach is to shoot the sequence out of order. The storyboard becomes a shooting plan.

To practice “storyboarding,” review a motion picture carefully, making a sketch of each key shot. This way, you will soon get into the habit of thinking in picture sequences rather than in isolated shots.

3.15 WHY PLAN?

Some people find the idea of planning restrictive. They want to get on with the shooting. For them, planning somehow turns the thrill of the unexpected into an organized commitment.

But many situations must be planned and worked out in advance. Directors need to get permission to shoot on private property, to make appointments to interview people, and to arrange access, among other tasks. They might occasionally have success if they arrive unannounced, but you can’t assume that. However, directors also need to be prepared to take advantage of unexpected opportunities. It is worth taking advantage of the unexpected, even if you decide not to use it later.

3.16 THE THREE STAGES OF PRODUCTION

Most programs go through three main stages:

1. Planning and preparation. Also known as preproduction, this phase of the production includes preparation, organization, and rehearsal before the production begins. Ninety percent of the work on a production usually goes into the planning and preparation phase.

2. Production. Actually shooting the production.

3. Postproduction. Editing the final project.

ANALYZING ACTION

FIGURE 3.18

When edited together correctly, a sequence looks natural. But even a simple scene showing a person buying a stamp needs to be thought through. Note how shots 1 and 3 are taken on one side of the counter and shots 2, 4, and 5 on the other.

(Illustration created by StoryBoard Quick software)

The nature of the subject will influence the amount of work needed at each stage. A production that involves a series of straightforward “personality” interviews is generally a lot easier to organize than creating an historical time-period drama. But in the end, a great deal depends on how the director decides to approach the subject.

Directors can create incredible programming by using simple methods. Treatment does not have to be elaborate to make its point. If a woman in the desert picks up her water bottle, finds it empty, and then the camera shows a patch of damp sand where it rested, the shot has told us a great deal without any need for elaboration. A single look or a gesture can often have a far stronger impact than lengthy dialog that attempts to show how two people feel about each other.

It is important to understand the complexity of the production. Some ideas seem simple enough but can be difficult or impossible to carry out. Others look very difficult or impracticable but are easily achieved on the screen. For example:

“Hurry and arc the camera around the actor.” (Difficult. Movement shots are always time-consuming, making it almost impossible to do quickly.)

“Make her vanish!” (Simple. Keep the camera still, have the subject exit, and edit out the walk.)

3.17 COVERAGE

What do you want to cover in the available time? How much is reasonable to cover in that time? If there are too many topics, it will not be possible to do justice to any of them. If there are too few, the program can seem slow and labored. There is nothing to be gained by packing the program full of facts; even though they may sound impressive, audiences rarely remember more than a fraction of them. Unlike the printed page, on video the viewer cannot refer back to check an item, unless the program is designed to be stopped, reversed, or is frequently repeated.

3.18 BUILDING A PRODUCTION OUTLINE

Directors often create a production outline. This begins with a series of headings showing the main themes that need to be discussed.

If we use the example of an instructional video about building a wall, the topics we may cover could include tools needed, materials, foundation, making mortar, and method of laying bricks. We can now determine how much program time to devote to each topic. Some will be brief and others relatively lengthy. While we will need to emphasize some of the topics, we will skip over others to suit the goal of the program.

The next stage is to take each of the topic headings and note the various aspects that need to be covered as a series of subheadings. Under “tools,” for instance, each tool that must be demonstrated should be listed. Once this program structure has been designed, the director can begin to see the form the program is likely to take.

3.19 BROAD TREATMENT

The next stage in the planning process will be to decide how to approach each subheading in the outline. Remember, you are still thinking things through. At this stage, the idea may even need to be altered, further developed, shortened, or even dropped altogether.

This is a question-and-answer process. Let’s imagine the situation:

What is the topic, and what is its purpose?

It is discussing “animal hibernation in winter.”

How will you approach it?

It would be nice to show a bear preparing its den for hibernation and settling down. Show the hard winter weather with the animal asleep. Later, show the bear waking up in the spring and foraging. And do all of this with a commentary.

■ This is a good idea, but where are the pictures coming from?

■ Are you using a film library’s services?

Let’s say that we cannot afford to obtain the pictures. We need to find a less expensive method.

You could have an illustrated discussion or a commentary over still photographs and drawings (graphics, artwork).

That could be boring, a little like a slide show.

Not necessarily, you could explore the still photographs with the camera, panning or tilting the camera across the photographs. The key is to keep the shots brief and add sound effects and possibly even music.

How do you find bear photographs that you can use?

You could take the photographs yourself in the wild or at a museum or zoo. Stills can also come from books (with permission), online stock photo agencies, or the private collections of photographers (Figure 3.19).

Note how each decision leads to another development. For example, if you decide that you are going to shoot photographs at a zoo, you then have to figure out how, when, and where you are going to get these shots. You have to figure out how the zoo needs to be lit. Will the glass cage cause reflection problems? Can you get the viewpoint you need? You may not be able to decide at this point, but you will have to do some research to see how feasible each specific idea is.

FIGURE 3.19

Photographs can be purchased from an online stock photo agency for use in video productions.

(Photo by Sarah Owens)

3.20 PRODUCTION RESEARCH

There are, in fact, several stages during the creation of a program when you will probably need more information before you can go on to the next step (Table 3.1). “Research” might amount to nothing more than hearing that Uncle David has a friend who has a stuffed bear that he would lend you for the program. Additional opportunities and problems will be discovered as research is being completed. Sometimes those oppor tunities and problems will even alter the outcome of the project. You may encounter an enthusiast who can supply enough material to fill a dozen programs on the subject, or you might have to really dig for program content.

3.21 REMOTE SURVEYS (RECCE)

Fundamentally, there are two types of shooting conditions: at your base and on location. Your base is wherever you normally shoot. It may be a studio, a theater, a room, or even a stadium. The base is where you know exactly what facilities are available (equipment, power, supplies, and scenery), where things are, the amount of room available, and so on. If you need to supplement what is there, you can usually do so easily.

A location is anywhere away from your normal shooting site. It may just be outside the building or way out in the country. It could be in a vehicle, down in a mine, or in someone’s home. Your main concern when shooting away from your base is to find out what you are going to deal with in advance. It is important to be prepared. The preliminary visit to a location is generally called a remote survey, site survey, or location survey. It can be anything from a quick look around to a detailed survey of the site. What you find during the survey may influence the planned production treatment. The checklist in Table 3.2 gives more remote survey specifics (Figure 3.20).

FIGURE 3.20

Site surveys allow you to check out the actual location to make sure it will meet the production needs.

3.22 FREEDOM TO PLAN

In practice, how far you can plan a production depends on how much control you have of the situation. If shooting a public event, planning may consist of finding out what is going on, deciding on the best visual opportunities, selecting camera locations, and so forth. The director may have little or no opportunity to adjust events to suit his or her production ideas.

If, on the other hand, the situation is entirely under the director’s control, he or she can arrange the situation to fit the production’s specific needs. Having planned the ideas, the director can then organize the elements of the production and explain the concept to the other people involved (Figure 3.21).

Table 3.1 Typical research information for the planning and preparation phase of the production process

| Lists can be daunting, but here are reminders of typical areas you may need to look into in the course of planning your production. | |

The Idea |

The exploratory process: ■ Find sources of information on the subject (people, books, and publications). ■ Select material that is relevant and appropriate to the idea. ■ Determine whom the program is for. ■ What is the purpose of the program? ■ Does it have to relate to an existing program? ■ Does the program need to be a specific length? ■ Coordinate ideas into an outline with headings and subheadings. ■ Consider the program development, forming a rough script or a shooting script. |

Practicality |

Consider the ideas in practical terms: ■ What does the viewer actually need to see and hear at each point in the program? ■ Where can the program be shot? ■ What sort of props are needed for each sequence? ■ How should the scene be arranged? ■ What talent (people in front of the camera) are needed for the program? |

The Equipment |

What is needed to shoot the program: ■ Single camera or multicamera? ■ What equipment, beyond the camera(s), will be required to make the production a success? ■ Is equipment not owned, can it be borrowed, or does it need to be rented? |

Feasibility |

Check what is really involved: ■ Are the ideas and treatment being developed reasonable for the available resources? ■ Is there another way of achieving similar results more easily, more cheaply, more quickly, or with less labor? ■ Are the locations available and affordable? ■ Is there sufficient time to do research, organize, rehearse, shoot, and edit the production? Costs: ■ What is the budget? ■ How will you arrange to research possible costs for a sequence before including it in the production? ■ Are advance payments required for some services and purchases? Assistance: ■ Will you need assistance to do the job? ■ What talent is involved (amateur, professional, casual)? ■ Do you need professional services (to make items, prepare graphics, etc.)? |

|

Facilities: ■ Are there facilities available that are sufficient for the anticipated shooting requirements and the postproduction? ■ Will additional facilities be needed to augment the existing facilities? Problems: ■ What might be the impact of major problems, such as weather, on each sequence of the production? ■ Is there any obvious danger factor (shooting a cliff climbing sequence)? ■ Will the situation you need be available at the time the program needs to be shot (snow in summer)? Time: ■ Is there sufficient time to shoot the sequence? ■ What backup plans must you make to protect the production in case serious problems arise? For example, instead of taking a couple of hours to shoot a scene, it might take 2 days with an overnight stay if things go wrong (high wind, rain, noise, etc.). |

|

Administration |

Various business arrangements and agreements: ■ Obtain permission to shoot, permits, fees, and so on. ■ Obtain copyright clearances for music, video, or photographs. ■ Insurance may be necessary to cover losses, breakage, injury. ■ Union agreements may need to be followed. ■ Contractual arrangements may be needed for the talent, crew, equipment, transportation, scenery, props, costumes, and editing suite. ■ Arrange for transportation, accommodation, food, and storage. ■ Return borrowed/hired items. |

Table 3.2 Checklist: The remote survey

The amount of detail needed for a location survey varies with the type and style of the production. Information that may seem trivial at the time can prove valuable later in the production process. Location sites can be interiors, covered exteriors, or open-air sites. Each has its own problems. |

|

Sketches |

■ Prepare rough maps of the route to the site that can ultimately be distributed to the crew and talent (include distance, travel time). ■ Prepare a rough layout of the site (room plan, etc.). ■ Outline anticipated camera location(s). ■ Designate parking locations for truck (if needed) and staff vehicles. |

Contact and Schedule Information |

■ Get location contact information from primary and secondary location contacts, site custodian, electrician, engineer, and security; this includes office and cell phones as well as e-mail. ■ If access credentials are required for the site, obtain the procedure and contact information. ■ Obtain the event schedule (if one exists), and find out if there are rehearsals that you can attend. |

Camera Locations |

■ Determine the best locations for the cameras. ■ What type of camera mount will be required (tripod, Steadicam, etc.)? ■ If a multicamera production, cable runs must be measured to ensure that there is enough camera cable available. ■ What lens will be required on the camera at each location to obtain the needed shot? ■ Are there any obstructions or distractions (e.g. large signs, reflections)? |

Lighting |

■ Will the production be shot in daylight? How will the light change throughout the day? Does the daylight need to be augmented with reflectors or lights? ■ Will the production be shot in artificial light? If so, will you use theirs, yours, or a combination of the two? ■ What are your estimates for the number of lights, positions, power needed, supplies, and cabling required? |

Audio |

■ What type of microphones will be needed? ■ Any potential problems with acoustics (such as a strong wind rumble)? ■ Any extraneous sounds (elevators, phones, heating/air conditioning, machinery, children, aircraft, birds, etc.)? ■ Required microphone cable lengths must be determined. |

Safety Power |

■ Are there any safety issues that you need to be aware of? ■ What level of power is available, and what type of power will you need? This will differ greatly between singlecamera and multicamera production. ■ What types of power connectors are required? |

Communications |

■ Are radios needed? How many? ■ If it is a multicamera production, what type of intercom and how many headsets are required? |

Logistics |

■ Is there easy access to the location? At any time, or at certain times only? Are there any traffic problems? ■ What kind of transportation is needed for talent and crew? ■ What kind of catering is needed? How many meals? How many people? ■ Are accommodations needed (where, when, how many)? ■ If the weather is bad, are there alternative positions/ locations available? ■ Has a phone number list been prepared for police, fire, doctor, hotel, and local (delivery) restaurants? ■ What kind of first-aid services need to be available? (Is a first-aid kit sufficient, or does an ambulance need to be on-site?) ■ Is location access restricted? Do you need to get permission (or keys) to enter the site? From whom? ■ What insurance is needed (against damage or injury)? |

Security |

■ What arrangements need to be made for security of personal items, equipment, props, etc.)? ■ Do streets need to be blocked? |

3.23 SINGLE-CAMERA SHOOTING

When shooting with a single camera, the director is usually in one of two situations:

■ Planning in principle and shooting as opportunity allows. For example, the director intends on taking shots of local wildlife, but what is actually shot will depend on what the crew finds at the location (Figure 3.22).

FIGURE 3.21

During the flow of the video production process, the production meetings provide a forum for all parties involved in the production to hear the vision, share ideas, and communicate issues.

■ Detailed analysis and shot planning. This approach is widely used in filmmaking. Here the action in a scene is reviewed and then broken down into separate shots. Each shot is rehearsed and recorded independently. Where action is continuous throughout several shots, it is repeated for each camera viewpoint. It is regular practice to shoot the complete action in one LS and then take CUs separately. These individual shots can then be relit for maximum visual effect.

■ Shot 1. LS: An actor walks away from the camera toward a wall mirror.

■ Shot 2. Medium shot (MS): The actor repeats the action, approaching the camera located beside the mirror.

■ Shot 3. CU: The actor repeats the walk as the camera shoots into the mirror, watching his expression as he approaches.

When edited together, the action should appear continuous. It’s essential to keep the continuity of shots in mind throughout.

FIGURE 3.22

Single-camera shooting

3.24 MULTICAMERA SHOOTING

When shooting with two or more cameras, a director tends to think in terms of effective viewpoints as well as specific shots. Cameras need to be positioned to capture specific shots, but they also need to catch various aspects of the continuous action (Figure 3.23).

FIGURE 3.23

Multicamera shooting allows the director to think in terms of effective viewpoints rather than specific shots.

(Photo by Jon Greenhoe/WOOD TV)

When planning a multicamera production, directors have to consider a variety of situations:

■ Will one camera come into another camera’s shot?

■ Is there time for cameras to move to various positions?

■ What kinds of shots does the script dictate?

■ How will the microphones and lighting relate to the camera’s movements (visible mics or shadows cast by the boom pole, etc.)?

3.25 BUDGETING

It is understandable that most directors are more creative minded than business minded. However, you have to be financially savvy in order to stay within the budget constraints—and every production has budget constraints.

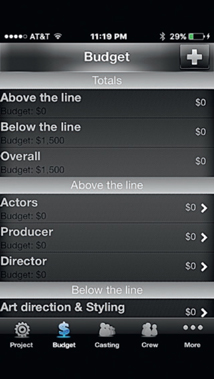

In Table 3.1, in the feasibility study, we talked a little about budgeting. It is important to understand what you have available financially at the beginning of the project. Once the total budget has been established, it needs to be broken down into categories. The categories may include but are not confined to the following:

■ transportation

■ staff/crew

■ talent/actors

■ script

■ equipment costs (rental or purchase)

■ postproduction

■ props

■ permits

■ food

■ lodging

■ supplies.

An estimate needs to be made for each category. Once the estimates are completed, you can see if your project is going to fit the assigned overall budget. Most of the time you will need to trim here and there in order to fit the budget. However, occasionally you will see that you have some extra money in the budget, allowing you to increase a category or two (Figure 3.24).

Once the budget is final, it is important to begin tracking each expenditure. This enables you to keep an eye on the categories as well as the overall budget. If you go over in one category, it means that you have to take money from a different category—or you will go over budget.

FIGURE 3.24

Budgeting software keeps track of production expenses, comparing the estimated costs with the actual costs. Computer software is available to keep a very detailed budget. Mobile software that works on a portable device is helpful when in the field. This is a screenshot from a smart phone budgeting app called Producer.

Building a track record of being able to stay within budgets will increase the trust that clients have in you, knowing that you can responsibly create productions.

3.26 COPYRIGHTS

If you can’t get permission from the copyright owner, you probably need to remove the item from the scene. Whenever material prepared and created by other people is used—a piece of music, a sound recording, video footage, a picture in a book, labels on a jar, CD covers, a sculpture, a photograph, and so on— it must be cleared for use in your production if it will be seen beyond the educational classroom. The copyright may even include artwork and trademarks, and it must be cleared with the appropriate copyright owner(s). Many times the producers/directors are required to pay a fee to the copyright holders or an appropriate organization operating on their behalf for copyright clearance. The copyright law is complex and varies among countries, but basically it protects the originators from having their work copied without permission. You cannot, for example, prepare a video program with music dubbed from a commercial recording, with inserts from television programs, magazine photographs, advertisements, and so on without the permission of the respective copyright owners. Copyright fees will depend on the purpose and use of the program. Some of the exceptions to this policy occur when the program is only to be seen within the home or used in a class assignment that will not be seen by the public. In most cases, the copyright can be traced through the source of the material needed for the production (the publisher of a book or photograph).

Agreements take various forms. They may be restricted or limited. For music and sound effects, directors are usually required to pay a royalty fee per use, or it may be possible to buy the rights to use an item or a package (“buyout method”).

The largest organizations concerned with performance rights for music (copyright clearance for use of recorded music or to perform music) include the Performing Rights Society (PRS) in the United Kingdom, the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), the Society of European Stage Authors and Composers (SESAC), and Broadcast Music Inc. (BMI). When clearing copyrights for music, both the record company and the music publishers may need to be involved.

Music in the public domain is not subject to copyright, but any arrangement or performance is. Music and lyrics published in 1922 or earlier are in the public domain in the United States. While anyone can use a public domain song in a production, no one can “own” a public domain song. Sound recordings, however, are protected separately from musical compositions. There are no sound recordings in the public domain in the United States. If you need to use an existing sound recording, even a recording of a public domain song, you will either have to record it yourself or license a recording.

3.27 CONTRACTS

Whenever you hire talent (actors, talent, and musicians) or use services (such as a scaffolding company), contractual agreements arise. Union agreements may also be involved. So before you commit in any way, find out exactly what is entailed both financially and legally.

Apart from general shots, whenever you want to shoot in the street, it is wise to let the local police know in advance. Productions may cause an obstruction or break local laws. If you are going to be shooting footage of people, you are required to get their permission in writing (with their name and address) on a talent release form (Table 3.3). While terminology varies, depending on the purpose of the production and the nature of the actor’s contribution, the release form generally authorizes the director to use the individual’s performance—free or for a fee.

Table 3.3 Sample talent release form

Video Project Title: _____________________________

I hereby consent for value received and without further consideration or compensation to the use (full or in part) of all video recordings taken of me and/or recordings made of my voice and/or written extraction, in whole or in part, of such recordings or musical performance for the purposes of broadcast, cybercast, or distribution in any manner by

_____________________________(production company name).

Date: _______________

Talent’s or legal guardian’s signature: ____________________

Address: ________________ City: ________________

State: ______________ Zip code: _____________ Date: ___/___/___

D.T. Slouffman

What do you like about being a producer?

■ Producing affords me the opportunity to collaborate with a team—other producers, shooters, editors, and talent—while still exercising a certain amount of creative control over the project and the process.

■ I often have the opportunity to assemble and manage my own team. Putting the right people in the right roles can make or break a production.

■ My favorite thing about producing is the results. Like any artist, to have a body of work that you created to be enjoyed by others, it’s even more rewarding when that product can help or encourage its respective audience.

Tell me about how communication works in the organization of a production.

If the end goal of your work is to communicate with an audience, then you better be able to communicate to the team working with you. I have seen many productions implode or fizzle out because the producer at the top was super creative, maybe even a visionary, but unable to effectively communicate the vision with the production personnel. Without communication, the execution was flawed or the production rendered inferior or ineffective.

How do you deal with communicating to everyone?

In this age of postmodern technology, there are limitless choices when it comes to communicating with the team working with me and for me. I cannot count the number of e-mails, texts, phone calls, and voicemails I receive daily. From preproduction to postproduction I have to make sure that schedules and scenarios are readily available for every member of the team and accurate. However, the most important document for any production, even more important than the budget, is the contact sheet. This is usually a one-page document that is compiled during preproduction and updated until the production is complete. The contact sheet contains the name, position, cell phone number, and e-mail of everyone working on the production. I keep an electronic copy on my laptop, an attached copy in my saved e-mail, and a printed copy folded in my wallet.

What challenges do you have to deal with as a producer?

The biggest challenge for me on any production is dealing with people who do not work in the business and don’t automatically understand why I may be doing things a certain way.

FIGURE 3.25

DT Slouffman, Producer.

A large part of any nonfiction production is dealing with the everyday people you are following and interviewing. They don’t work in the business and often have a hard time answering questions in a way that their answer makes sense on television.

I always feel like I am teaching a small television class with the people that I am making shows about. It truly is the most challenging part of my job, but if I cannot communicate the how and why to the people my series will be about, I won’t get what I need, and the finished episode will suffer.

How do you prepare for a specific assignment as a producer?

I prepare for every production that I produce by doing massive amounts of homework. I need to know everything I can know about the subject matter of the show and the people we will follow in the process of shooting. You cannot know too much about your subject because you will follow and interview people who will know the subject intimately. If you don’t have a working knowledge of what you are covering, you will fail while working with them.

As well, if you bluff your way through it, your audience will know. Remember that in most cases your demographic chooses what they watch because the subject is interesting to them. If you are heading up a production and you don’t truly understand the subject you are covering, the audience always knows.

Effective producing involves managing people, understanding how to tell a story, and working well with others. You can be great at all of those things, but if you haven’t done your homework, when it comes to your subject matter, none of those things can save you.

DT Slouffman has worked on productions for ABC, NBC, Lifetime, and CNN and is currently an Executive Producer at Sports Illustrated.