CHAPTER 1

Overview of Video Production

Please answer the TV set. I am watching the phone.

Stefan Kurten, Director of Operations, European Broadcast Union

1.1 WHAT IS VIDEO PRODUCTION?

The differences between “video production” and “television production” have blurred over the years. Most video productions are created for nonbroadcast. Video productions are generally distributed with nonlinear accessibility such as online, mobile phones, or via DVDs. Although video productions are generally made with a lower budget, it does not mean that fewer people see them. A simple tour of YouTube will show that millions of people are looking at video productions every day (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1

YouTube is a collection of both high-budget and low-budget video productions that millions of viewers watch online. Note that the video shown has been seen by close to 5 million viewers.

Television productions, on the other hand, were historically shown to a public audience by broadcast or cable transmission in a linear fashion. Television broadcast transmissions are required to conform to closely controlled technical standards established by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). However, television productions may be considered to be a type of video production once they are distributed in a nonbroadcast method such as online. As you can see, the definitions can be blurry.

With the high quality of consumer and prosumer equipment, video productions can be made with equipment ranging from the most sophisticated professional broadcast/cinema standards to low-cost consumer items (Figure 1.2). There is no intrinsic reason, though, why the final video productions should differ in quality, style, or effectiveness as far as the audience is concerned. Video programs range from ambitious presentations intended for mass distribution to economically budgeted programs designed for a specific audience. This book will help you, whatever the scale of your production.

FIGURE 1.2

High-quality consumer equipment allows professional results—if you understand how to use it effectively.

(Photo courtesy of SVG)

1.2 DEFINING THE NEW MEDIA

There is always a question about what “new media” is and how it fits in with television and video production. “New media” is a term often used to describe a new distribution method. When the European Broadcast Union recognized that its members did not understand the definitions, it worked with those members to define the term. The organization’s basic question was, how can we distinguish broadcast television from any of the new means of distribution? The organization adopted two basic terms: linear service and nonlinear service.

Television is considered a linear service—that is, the broadcasting of a program where the network or station decides when the program will be offered, no matter what distribution platform is used. Although there are many new distribution platforms (Internet, smart phones, tablets, satellite), if television uses the platform, it is a linear service.

On the other hand, the nonlinear services (traditionally called “video”) equal the new media, which means making programs available for on-demand delivery. It is the demand that makes the difference.

1.3 UNDERSTANDING THE FIELD OF VIDEO PRODUCTION

Video production appears deceptively simple. After all, the video camera gives us an immediate picture of the scene before us, and the microphone picks up the sound of the action. Most of us start by pointing our camera and microphone at the subject but find the results unsatisfying. Why? Is it the equipment or us? It may be a little of both. But the odds are that we are the problem.

As you may have already discovered, there is no magic recipe for creating attractive and interesting programs. All successful production emerges from a knowledge base of the equipment, production techniques, and video production process:

1. Knowing how to organize systematically. Applying practical planning, preparation, and production.

2. Knowing how to use the equipment effectively. Developing the skills underlying good camerawork and sound production. Understanding the effects of the various controls.

3. Knowing how to convey ideas convincingly and how to use the medium per suasively.

As you work through this book, the knowledge you develop will soon become a natural part of your approach to creating a production. Knowing what the equipment can do will enable you to select the right tools for the job and use them in a way that effectively communicates your story.

1.4 REMEMBER THE PURPOSE

If we simply produce a flow of TV images for mobile phones, then probably we shall simply say, “Well, this is just a gadget.” But, on the contrary, if we create formats, which are specific to this new platform, then we shall be able to meet [or exceed] the consumers’ expectations.

Patrick Chene, Former Head of Sport for France Televisions

There is no shortcut to experience. The more time you work with the equipment, the more it becomes natural. After a while, you don’t think as much about the equipment, allowing you to think more about the content of the production.

Some new camera operators have tried to show how good they are by quick moves, fast zooms, and attention-getting composition—where an experienced camera operator would have avoided these distractions and held a steady shot, letting the subject work to the camera instead. Smooth, accurate operation is important, but appropriateness is even more desirable. In the end, it is audience impact that really counts—the effect the chosen camera treatment has on the viewer.

1.5 IS THERE A RIGHT WAY?

Creating a video production is a subjective process. It is often pretty easy to learn the basic mechanics of the equipment, but learning how to use that same equipment to persuade an audience and influence their reactions is another matter entirely. Some “creative” or “original” production styles can be a pain to watch, such as a rapid succession of unrelated shots or fast cutting between different viewpoints. Amateurs who use these techniques hope to create an illusion of excitement for a dull subject. After a while, however, these techniques only succeed in annoying, confusing, or boring the audience.

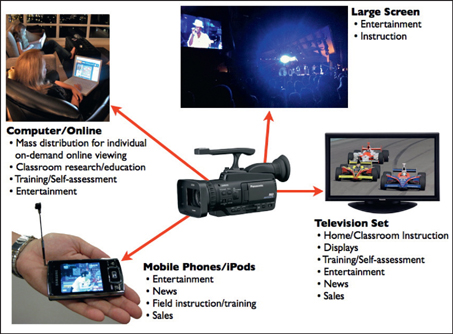

FIGURE 1.3

There are many different ways to present your content. We have listed some of the most popular production formats here. A combination of these approaches is often used to best communication to the audience.

You can learn a lot by studying videos, television shows, and films, particularly those covering the topics you are interested in emulating. Review them over and over, and you will see that while some approaches are little more than stereotyped routines, others have an individuality and flow that is appropriate for the subject matter. Adjust your own approach to fit the situation rather than imitating the way things have always been done. If your production does not have the impact you are aiming for, you need to do it differently (see Figure 1.3).

1.6 THE PRODUCTION APPROACH

If content is king, then content delivery is the power behind the throne. Reaching the audience requires knowledge of not just what they are watching, but how and where.

Chris Purse, HD magazine

When you are preoccupied with ideas about how the subject should be covered, it’s easy to overlook some of the issues that need to be thought about, such as budgets, availability of facilities, labor, materials, scheduling, safety issues, weather conditions, transportation, accommodations, legalities, and so on. Again, a lot is going to depend on the desired program. At the same time, the production will inevitably be affected by the expertise and experience of the production crew, the program budget, the equipment being used, the time available, and similar factors (see Figure 1.4). With a little imagination and ingenuity, you can often overcome limitations or at least leave your audience unaware that there were any. Later we will explore typical strategies that enable you to do just that.

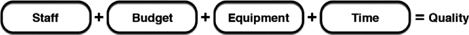

FIGURE 1.4

The quality of a video production is primarily affected by these four areas.

At an early stage directors should have given a great deal of thought about the production and the audience, settling basic questions such as these:

■ What is the program’s main purpose? Is it to educate, entertain, excite, or intrigue? Are specific methods being demonstrated, such as showing how to make or repair something? Is the goal to persuade the audience—for example, to visit a specific place or to make a purchase … or is the goal to warn them against doing so?

■ Who is the program being made for? Is the intended audience an individual or a group? What are their ages? What production methods are most effective for the targeted group? Is it for the general public or for a specific audience?

■ How will the production be seen? Will the production be viewed online, on a mobile phone, or on a large screen? Will it appear on broadcast television or on a niche cable channel? Is it targeted at prospective customers in a store (such as an advertising display), for delivery to a student group at a school, or for an in-house corporate symposium? Perhaps it is intended for home study on an iPad?

The style that is adopted for the production, the pace of delivery, and how much to emphasize various points are all determined by the program’s ultimate purpose.

1.7 EQUIPMENT

Don’t get too enamored with the hardware. You do not need elaborate or expensive facilities to produce successful productions. Even the simplest equipment may provide the needed essentials. It really depends on the type of production you are creating. For some purposes, one camera is ideal. For others, a dozen may be insufficient.

What is done is more important than how it is done. If it is possible to get an effective moving shot along a hospital corridor by shooting from a wheelchair rather than a special camera dolly, the audience will never know—or care (Figure 1.5).

Sometimes special effects on equipment can tempt the camera operator to use them because they are there rather than because they are needed. Sometimes wipes, star filters, or diffused shots are in the wrong place or at the wrong time, just for the sake of variety and because they are readily available. What appears at first sight to be a sophisticated, stylish presentation may have far less impact on the audience than a single still shot that lingers to show someone’s expression.

It’s funny to me that I’m pretty against auto settings, but I’m going to be working on a piece soon that’s going to be 75 percent iPhone video. Videography seems to be going two ways: super-fast and easy (iPhones and GoPro-type cameras), and high-quality HD/4K cinematography. The audience seems fine with both, depending on the situation. Being able to adapt is key right now.

Nathan White, Videographer

FIGURE 1.5

This videographer connected his DSLR to an off-the-shelf remote controlled toy truck to create a tracking camera for a music video.

VERSATILITY OF VIDEO

Video Medium

■ Images can span from the microscopic to the infinities of outer space;

■ several video sources can be combined (inset, split screen);

■ video can be modified and manipulated (color, tonal values, shape and form, sharpness, etc.).

Video Presentation

■ The video picture can be shown on screens that range from pocket-sized to giant displays or from a single screen to a “videowall” (multiscreen) display (see Figure 1.6).

■ Videos can be shown by themselves or combined with other media such as a PowerPoint or on a website.

■ The video signal can be distributed instantly by cable (wire, fiber-optic), Wi-Fi, microwave, infrared link, or satellite.

■ Videos can be stored online to be downloaded whenever it is convenient for the viewer.

■ Video artwork and titles can be created electronically (computer graphics).

■ While historically video has been shot for a horizontal screen, the increased popularity of mobile phone video and the placement of video on websites has opened the door to vertical video images.

Video Recording

■ The video signal can be stored in different forms (flash memory, hard drive/server, DVD, and online).

■ Video recordings can be played back immediately and replayed many times. They can be stored indefinitely.

■ Video recordings can be reproduced at faster or slower speeds than normal. A single moment of action can be frozen (“still frame,” “freeze frame”); a day’s events can be played back in a few seconds using time-lapse recording.

■ Recorded programs can be edited to delete faulty or irrelevant shots, enhance the presentation, adjust program duration, and so on.

FIGURE 1.6

Video productions can be shown on many different media.

1.8 IT’S DESIGNED FOR YOU

Most production equipment has been designed for quick, uncomplicated handling. After all, it is there for one fundamental purpose—to enable users to communicate their ideas to an audience. Video equipment is as much a commu nication tool as a computer or a cell phone.

1.9 LEARNING BASICS

It is not important to know how every function of how the equipment works, but it is important to know its capabilities in order to get reliable results. Even with the most sophisticated video and audio equipment, you need to answer only a handful of basic questions to use it successfully:

■ What can it do?

■ What are its limitations?

■ Where are the controls and indicators (menus, buttons, etc.)?

■ How and when should they be adjusted and what will the result be?

1.10 WHAT EQUIPMENT IS NEEDED?

Let’s take a look at the types of issues that affect the equipment you will need. When working with a larger production, a wide range of facilities is usually available. Extra items can be rented from a rental house or production facility. Look through any manufacturer’s or supplier’s catalog or a video magazine to see the endless variety of equipment available.

On the other hand, a small production may need to work within the limitations of existing equipment, unless it proves possible to augment it in some way. A lot is going to depend on the kind of program that you are making and on your specific approach to the subject:

■ Production style. There is no single way every production must be created— they can be tackled in a variety of ways. Each style will have its merits and its drawbacks. Suppose, for example, you are shooting two people talking together (an interview or general conversation). You can treat this formally, by shooting them seated at a desk, or informally, by shooting them while they are resting in easy chairs. But to create a more natural ambience you might show one of them working at a task, such as gardening, while the other looks on. Alternatively, you might shoot them walking side by side along a pathway. Another familiar approach is to shoot them within a car as they drive to their destination. The content of the production often influences the production style.

■ Limitations. Every production will have its own types of limitations for cam era and sound treatment. In one situation, the camera may need to be held firmly on a tripod; in another, the camera will probably need a dolly; while in another, it will be necessary to carry the camera on your shoulder or even attach it to a car. Clearly, how one shoots the action and where it takes place will affect the selection of the optimum gear for the job.

■ Shooting circumstances. Obviously, equipment that is essential for some situations, like an underwater camera, proves unsuitable for other projects. While a robust camera mounting is necessary for continuous shooting, it can become an encumbrance if the camera constantly needs to be repositioned in crowded surroundings. At times, even a microphone may be superfluous if the shoot does not need audio, since sound content can be added during the postproduction (Figure 1.7).

FIGURE 1.7

Shooting circumstances will determine some of the camera mounts. In this situation, the production is being shot from a dolly.

(Photo by Katie Oostman)

1.11 EQUIPMENT PERFORMANCE

Thanks to good design and engineering, the majority of even the most complex television equipment will perform faultlessly for long periods of time with little attention. But it is good practice to make regular checks and carry out routine maintenance.

It is simple enough to check that parts are clean (lenses) and that controls are working correctly and ready for use. However, it is also important to study the instruction manuals that come with the equipment to know how to carry out the basic equipment checks and adjustments. If you are not an engineer, you may need the services of an experienced engineer to maintain equipment performance up to specification. But remember, don’t tweak (adjust) internal controls unless you know what you are doing.

Ben Brown, Media Executive

FIGURE 1.8

Ben Brown, Media Executive.

Tell me about the future of video and television.

I believe we are in a transition, and the future will look much different from what we have now. With video on demand (VOD), web and multiple other sources for content, broadcasters are faced with an overall shrinking and fractionalized audience. Over-the-air stations already struggle to stay financially viable as cable networks receive subscriber fees. However, once you get past the top five or six cable networks, the ratings plummet and the difference between the 35th and 70th place networks is less than a 0.5 share.

Once the economics are sorted I think the delivery method will be the biggest change. More and more content will be coming through broadband-based sources as the next generation has already acclimated itself to watching programming they want on their schedule (my 6-year-old is already proficient at navigating the cable system to select specific shows and cartoons from the kids on-demand channels).

How is video/television changing?

With fractional viewership and the emergence of more web-based content, how we receive programming is changing, and how/what is programmed is changing. As more programming moves to the web, typical half-hour and full-hour shows are no longer the norm. Episodes can be 6 minutes or 76 minutes. Additionally, programming will be more focused on specific target audiences.

Advertising will also change, as advertisers now are already moving away from the standard 30-second spot to 15- and even 10-second models. You will see more embedded advertising and more strategic placement.

In your mind, what is the difference between video and television?

Television has traditionally been thought of as coming over-the-air (broadcast) or via “cable.” Video is content, which may be transmitted via traditional methods or over broadband, web, or other on-demand methods. However, the boundaries between television, video, and even film have eroded. Today the words “video” and “television” are often used interchangeably.

What challenges do you see for video and television in the future (or now)?

I see challenges in two areas:

1. Content: With the fractionalization of audiences, more content is needed. However, with the proliferation of inexpensive gear/edit systems, the ability to produce content has increased, but the ability to put together well-thought-out, well-written and/or well-edited products has decreased exponentially. Everyone thinks they can edit or shoot—just because they can operate the software or point the camera—but they can’t answer the “why” behind what they do. And good writers are just as rare as they ever have been (and good stories even rarer!).

2. Financial: In a related corollary to the above, the proliferation of outlets for content that has led to the increased demand has also brought with it the fractionalized audiences, which means smaller share and less associated revenue. So paying for programming and content is becoming ever more difficult, as is evidenced by the number of mainstream outlets gobbling up perpetual re-air rights for reruns of older programming.

What are some of the basics that people need to know to get into this field?

Meet people. I have never been hired for a job based on just submitting my resume, and have never hired anyone just from a resume submission. Have the right attitude; no one really wants to work with a know-it-all or an “Eeyore.” Once you are hired, be the best at that position that is humanly possible. Trust me—someone will take notice. Keep your eyes open. Look for opportunities to fill a niche, or apply for positions that don’t even exist—yet. Resumes are well and good and can lead to getting hired, but most jobs I found, I found because I knew someone, or knew someone that knew someone. Talk with anyone willing to talk to you. They may not have a job open, or even be the person with the authority to hire, but if they are willing to talk, see what you can glean from them, and at the same time you are exposing yourself to another connection.

Ben Brown is a Managing Partner at Event Support Services. They create programming for television networks.