CHAPTER 4

Production Techniques

You can’t assume that you can take a 30-second ad and make it fit everything; put it at the end of something, put it on YouTube, get it in a banner or create a website around it. Content must be translatable and it has to be conceived to translate. Shooting with multiplatforms in mind and repurposing it for mobile, web, cinema, banners, is what companies are working toward.

David Rolfe, Senior Vice President, DDB Chicago

The production techniques that video crew members employ vary greatly from person to person, company to company, and country to country. The goal of this chapter is to review the most common production techniques in order to broadly prepare you for the television industry.

Key Terms

■ Camera control unit (CCU): Equipment that controls the camera from a remote position. The CCU includes setting up and adjusting the camera: exposure, black level, luminance, color correction, aperture, and so on.

■ Clapboard: The clapboard (also known as a clapper or slate) is shot at the beginning of each take to provide information such as film title, names of the director and director of photography, scene, take, date, and time. Primarily used in dramatic productions.

■ Continuity: The goal of continuity is to make sure there is consistency from one shot to the next in a scene and from scene to scene. This continuity includes the talent, objects, sets, and so on. An example of a continuity error in a production would be when one shot shows the talent’s hair combed one way and the next shot shows it in perfect condition.

■ Cut: An instantaneous transition between two images. This is the most common switcher transition used in production. (Also known as a “take.”)

■ Dissolve (mix): A gradual transition between two images. A dissolve usually signifies a change in time or location.

■ Dolly (track): To move the whole camera and mount slowly toward or away from the subject.

■ Fade in/out (up/down): A fade is a transition to or from “video black.” Usually defines the beginning or end of a segment or program.

■ ISO: While all the cameras are connected to the switcher as before, the ISO (or isolated) camera is also continuously recorded on a separate recorder.

■ Objective camera: The camera takes on the role of an onlooker who is watching the action from the best possible position at each moment.

■ Pan: To pivot the camera to the left or right.

■ Stand by: To alert the talent to stand by for a cue.

■ Stretch: To tell the talent to go more slowly (there is time to spare).

■ Subjective camera (point of view/POV): When the camera represents the talent’s point of view, allowing the audience to see through the talent’s eyes, as the camera moves through a crowd or pushes aside undergrowth.

■ Switcher (vision mixer): A device used to switch between video inputs (cameras, graphics, video players, etc.).

■ Take: See Cut.

■ Truck (crab): To move the whole camera and mount left or right.

■ Wipe: A special-effect transition between two images. Usually shows a change of time, location, or subject. The wipe adds novelty to the transition but can easily be overused.

4.1 SINGLE- AND MULTICAMERA PRODUCTION

There are two radically different ways of shooting a video production:

■ Single-camera production, in which one camera is used to shoot a segment or an entire show.

■ Multicamera production, in which a production switcher (vision mixer) links two, three, or more cameras, and their outputs are selected by the director.

Each of these techniques has its own specific advantages and limitations. Some types of programs, such as sports, cannot be shot effectively (such as recording an entire game) with a single camera; for other program types, a multicamera approach can seem overpoweringly inappropriate (such as a news interview in someone’s home). From the director’s point of view, the production techniques are markedly different. For a live production, a single camera could be unnecessarily inhibiting. If a single camera output is recorded, the director can adopt techniques that are similar to those of a filmmaker, shooting from different angles and then editing the footage together (Figure 4.1).

FIGURE 4.1

Single-camera news production.

Single-Camera Production

A single lightweight camera is independent (has its own recorder or trans mitter), compact, and free to go anywhere (is not attached by a cable to a switcher). The director can be next to the camera, seeing opportunities and explaining exactly what he or she wants to the camera operator. In many cases, the person devising and organizing the project may also be operating the camera (Figure 4.2).

FIGURE 4.2

Documentaries are generally shot with a single camera.

PREPARING TO RECORD A SINGLE-CAMERA SHOT (DRAMATIC STYLE)

■ Review details of the next shot from the storyboard.

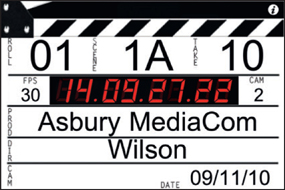

■ Mark clapboard with scene and shot numbers (optional, primarily used with dramatic productions) (Figures 4.3 and 4.4).

FIGURE 4.3

“Slating” the beginning of a take with a clapboard.

FIGURE 4.4

Clapboards can be an actual board, in seen in Figure 4.3, or they can be on a mobile devise such as a mobile phone or tablet. This image is from a smart phone app called iSlate.

■ Announce “Is everyone ready?”

■ Call “Quiet, please!”

■ Start recording.

■ Shoot clapboard.

■ Call “Action!” (Cues action to begin.)

■ Announce the end of action. “Cut!” (Action stops, talent waits.)

■ Stop recording.

■ Possibly check recording (end only, or spot check).

■ Note final frames for continuity, log shot details (identification, duration), and label the recording (Figure 4.5).

■ One of the following is then appropriate:

“Take is OK. Let’s go on to shot 5.”

Or

“We need to retake that shot because …”

FIGURE 4.5

A production assistant is logging the shots the camera operator is shooting. She is responsible for noting the content of shots. Loggers may also note shot durations, whether it is a good or bad shot, and any other pertinent notes.

This method offers the director incredible flexibility—both when shooting and later when editing. Directors can select and rearrange the material they have shot, trying out several versions to improve the production’s impact. There is none of the feeling of instant commitment, which can typify a multicamera production. But it is slow, and patience is a necessity.

Shooting with a single camera will often involve interrupting or repeating the action in order to reposition the camera. The problems of maintaining continuity between setups, even the way in which shooting conditions can change between takes (such as light or weather variances), are not to be underestimated.

It has been said that, unlike multicamera production, which is a “juggling act,” shooting with a single camera allows the director to concentrate on doing one thing at a time, on optimizing each individual shot. The director is free to readjust each camera position, rearrange the subject, change the lighting, adjust the sound recording, modify the decor, and make any other changes that are necessary to improve the shot. That’s great. But shooting can degenerate into a self-indulgent experimental session. It is all too easy to put off problems until tomorrow with “We’ll sort it out during the edit” or “Let’s leave it till postproduction.”

When shooting with a single camera, directors do not have to worry about coordinating several different cameras, each with its different viewpoint. Direc tors are relieved of the tensions of continually cueing, guiding, and switching between cameras. All production refinements and supplementary features from background music to video effects are added at a later stage, during the postproduction session. The other side of the coin is that when shooting with a single camera, you finish with a collection of recordings containing a mixture of takes (good, bad, and indifferent; mistakes and all) shot in any order, all needing to be sorted out at a later time. So compiling the final production— including titles, music, and effects—can be a lengthy process.

Multicamera Production

If you are shooting continuous action with a single camera and want to change the camera’s viewpoint, you have basically two choices. You can move the camera to a new position while still shooting, or you can miss some of the action as the camera is repositioned at the next setup. A multicamera production director simply switches from one camera to another, which is a clear advantage when shooting a series of events going on at the same time or spread over a wide area (Figure 4.6).

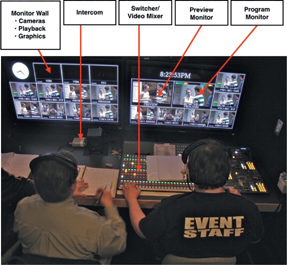

FIGURE 4.6

Multicamera productions provide flexibility in covering events by offering multiple camera shots to choose from.

FIGURE 4.7

Multicamera production in a studio.

FIGURE 4.8

The director (forefront) is giving directions to the technical director (background) and the crew in the studio.

Unlike the director on a single-camera shoot, who is close to the camera, the director of a multicamera production is located away from the action. This director watches a series of television monitors in a production control room and issues instructions to the crew over their intercom (talkback) headsets and to the FM who guides the talent on the director’s behalf (Figures 4.7 and 4.8).

In a live multicamera production, most of the shot transitions (cuts, dissolves, wipes, etc.) are made on a production switcher (also known as a vision mixer) during the action. The switcher takes the outputs from various video sources (cameras, video recorders, graphics, etc.) and switches between them (Figure 4.8). There are no opportunities to correct or improve. However, the director does have the great advantage of continuously monitoring and comparing the shots (Figure 4.9). The continuity problems that can easily develop during a single-camera production disappear during the multicamera production because it is real time. An experienced multicamera crew can, after a single rehearsal, produce a polished show in just a few hours. At the end of the recording period, the show is finished.

Multicamera productions may be shot as follows:

■ Live. Transmitted live to the viewing audience.

■ Live-Recorded (live-on-tape). Shot from beginning to end and recorded. This style of production allows the director to clean it up in postproduction.

■ Scene-by-scene. Each scene or act is shot, corrected, and polished one at a time (Figure 4.10).

A multicamera production can degenerate into a shot-grabbing routine in which the director simply cuts between several camera viewpoints for the sake of variety. However, for directors with imagination, the ability to plan ahead, and a skilled team, the results can be of the highest standards.

FIGURE 4.9

Multicamera production directors receive a variety of visual options (camera shots, video playback, and graphics) all at the same time and must choose which one best communicates the message.

FIGURE 4.10

A sitcom is a good example of a scene-by-scene multicamera television production.

4.2 MULTICAMERA ISO

When the action cannot be repeated or events are unpredictable, some directors make use of an ISO (isolated) camera. This simply means that, while all the cameras are connected to the switcher as before, one of them is also continuously recorded on a separate recorder. This ISO camera takes WS of the action (cover shots) or concentrates on watching out for the arrival of the guest, for instance, or a specific player at a sports event, so that if the director misses the needed shot “live,” it is still recorded. Shots on ISO can be played back during a live show or edited in where necessary later.

4.3 MULTICAMERA PRODUCTION WITHOUT A SWITCHER

Another multicamera approach is to use camcorders. Instead of cutting between cameras with a switcher, shots from their separate recordings are edited together later during a postproduction session. It is fairly simple to sync multiple cameras together on even some of the lowest-cost nonlinear editing systems. Voiceover narration, sound effects, video effects, graphics, or music are then added in postproduction. The advantage of this type of multicamera technique is that it significantly reduces the cost of having to pay for a large crew and a control room or remote production truck/outside broadcast (OB) van. The disadvantage is that the production is not over when the event is over; it still needs to be finalized in postproduction, which can be time-consuming.

TELEVISION AND ILLUSION

Roone Arledge, former president of ABC News and Sports, was an early innovator in television sports production. Arledge pushed his directors to “use the camera—and the microphone—to broadcast an image that approximates what the brain perceives, not merely what the eye sees. Only then can you create the illusion of reality.” His example was an auto race where, even though cars may be traveling more than 200 miles per hour, the perception of speed disappears when a camera with a LS is used. However, when a small point-of-view (POV) camera is placed much closer to the track than spectators would normally be allowed, the close camera and microphone give the television viewer the sensation of speed and the roar that a live viewer would perceive by sitting in the stands. “That way, we are not creating something phony. It is an illusion, but an illusion of reality.”

4.4 THE ILLUSION OF REALITY

Some directors (and camera operators) imagine that they are using their cameras to show their audience “things as they are.” However, they are not. Television is inherently selective. Even if the camera is simply pointed at the scene, and the rest left to the audience, the director has, whatever the intention, made a selective choice on the audience’s behalf. The audience has not chosen to look at that specific aspect of the scene; the director has. The type of shot shown and the camera’s viewpoint determine how much the audience sees. The audience has no way of seeing the rest of the scene. In fact, a skilled director uses camera and microphone placement to create an illusion, to give the audience the impression of reality. The goal is to make viewers feel as though they are there, actually experiencing the event.

Program-making is a persuasive art—persuading the audience to look and to listen; persuading them to do something in a specific way; persuading them to buy something, whether it is an idea or a product. Directors not only want to arouse the audience’s interest but also to sustain it. The goal is to direct their attention to certain features of the subject and to prevent their minds from wandering to other areas. Directors achieve this goal by the shots they select, by the way they edit those shots together, and by the way sound is used. Persuasion is not a matter of high budget and elaborate facilities but of imagination.

Directors can even take a dull, unpromising subject, such as an empty box, and influence how the audience feels about it. Imagine you are sitting in darkness when up on the screen comes a shot containing nothing more than a flatly lit wooden box with a light gray background. How do you think the audience would react? On seeing the shot, most of us would assume that the image is important or is supposed to have some sort of meaning or purpose. After all, it is appearing on video. So we start by wondering what it is all about. What are we supposed to be looking at? Does the box have some significance that we’ve missed? Is someone coming on in a minute to explain?

Now the director has the audience’s attention for a moment or two while they are trying to understand what is going on. If a word is stenciled on the box, the viewers will probably read the word and then try to puzzle out what it means. They will look and listen, and finally get bored. But all that has probably only taken a few seconds. Directors cannot usually rely on the subject alone to hold the audience’s interest. How the subject is presented is very important.

Now, imagine the same box, appearing half-lit from behind with only part of the box visible as the rest falls away into a silhouette. A low rhythmical beat is playing. The camera dollies slowly along the floor, creeps forward very slowly, pauses, then moves onward, stopping abruptly before moving on again. The music grows louder and louder.

How is your audience going to react? If it has been done well, they are now on the edges of their seats, anxious to find out what is in the box. It is the same box that appeared in the first illustration, only you have now held your audience’s attention for much longer than a few seconds.

We know that these dramatic techniques cannot be used in all productions. However, it does show how persuasive video can be. It shows us how even a simple subject, like an empty box, can be influenced by production techniques. However, it is also a reminder that the production treatment needs to be appropriate. It needs to create an ambience, an atmosphere that is suitable for the occasion. Whether your program is to have Hollywood glitter, the neutrality of a newscaster’s report, the enthusiastic participation of a kids’ show, or the reverential air of a remembrance ceremony, the style of your presentation needs to fit the occasion.

4.5 THE CAMERA’S ROLE

The camera is an “eye.” But whose eye? It can be that of an onlooker, watching the action from the best possible position at each moment. This is its objective role. Or the camera can be used in a subjective way. Moving around within the scene, the camera represents the talent’s point of view, allowing the audience to see through the talent’s eyes as the camera moves through a crowd or pushes aside undergrowth. The effect can be dramatic, especially if people within the scene seem to speak to the viewer directly, through the camera’s lens.

INTERCOM INSTRUCTIONS

FIGURE 4.11

Directors use intercoms to give instructions to the crew. Sometimes the crew member then needs to give the director’s instructions to the talent.

(Photo by Katie Oostman)

In a multicamera production, the director gives instructions to the crew members (cameras, sound, etc.) through their headsets. Microphones, performers, or the viewing audience cannot overhear this intercom. It is only meant for the production crew (Figure 4.11).

| Ready to fade to 1 | Production is beginning in video black. Director is warning the TD and the camera 1 operator that he or she is going next to camera 1. |

| Fade to 1 | Gradual transition from video black to camera 1. |

| Ready to take 2 | Stand-by cue for camera 2. |

| Cam 2, give me a two-shot of the host and guest | Camera 2 operator should frame both people in the shot. |

| Zoom in (push in) | Use the zoom control on the lens to magnify the subject. |

| Tighten your shot | Slightly zoom in. |

| Go wider | Slight zoom out. |

| Dolly in/back | Move the whole camera and mount slowly toward/away from the subject. |

| Pan left/right | Pivot the camera to the left/right. |

| Lose the host | Recompose or tighten shot to exclude the host. |

| Stand by | Alert talent, ready for a cue. |

| Cue action/cue host | Give hand signal to the host to begin action. |

| Tighten them up | Move the people closer together. |

| Give the host a mark | Make a floor mark (tape) to show the host where to stand. |

| Tell talent to look at 2 | Talent should face camera 2. |

| Stretch | Tell talent to go more slowly (there is time to spare). |

| Tell talent to pad/keep talking | Tell talent to improvise until next item is ready. |

4.6 THE CAMERA AS AN OBSERVER

The program shows us the scene from various viewpoints, and we begin to feel a sense of space as we build up a mental image of a situation—although the camera is only showing us a small section of the scene in each shot. The camera becomes an observer, moving close to see detail and standing far back to take in the wider view.

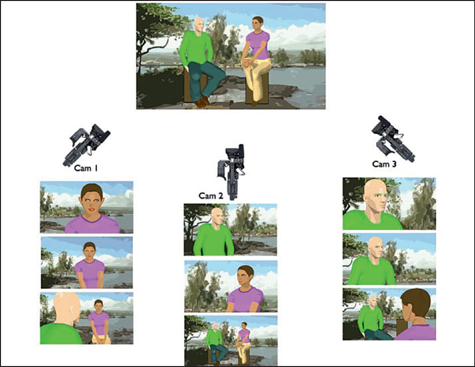

We might, for example, watch two people sitting and talking. As one speaks, we see a CU of the speaker. A moment later, the camera switches to show us the other person listening. From time to time, we see them together (Figure 4.12).

There is nothing imaginative about this treatment; but then, it is not intended to work on the audience’s emotions. It is intended to show us clearly what is going on, who is there, where they are, and what they are doing. It intermixes CUs to show the details we want to see at a specific moment (people’s expressions) with LS that help us establish the scene and give a more general view of the situation. In fact, treating a conversation in front of the camera in another way, by overdramatizing its presentation, would normally be inappropriate.

FIGURE 4.12

A basic three-camera shoot uses a mix of different shot angles to maximize communication.

4.7 THE PERSUASIVE CAMERA

If, on the other hand, you are shooting a music video, shots may be as bizarre and varied as you can make them. Your aim is to excite and to shock, to create great visual variety. There is no room for subtlety. Picture impact, strange effects, and rapid changes in viewpoint thrust the music at your audience (Figure 4.13).

There is a world of difference between this brash display and the subtle play on the emotions that we discussed earlier. Yet they all demonstrate how directors can influence the audience through the way they choose and compose their shots, move the camera, and then cut those shots together.

A high-angle shot looking down on the subject can suggest an air of detachment. A low-angle shot can exaggerate the subject’s importance. Tension increases as the camera dollies. These are typical ways in which the camera can affect the viewers’ responses to what they are seeing (Figure 4.14).

FIGURE 4.13

Shooting an entertainment video allows you to use creative techniques that may not be appropriate for other types of show such as a news production.

FIGURE 4.14

A low-angle shot exaggerates the grandeur of a scene while a high angle shot can diminish the grandeur.

4.8 HOW DO YOU VISUALIZE SOMETHING THAT DOES NOT EXIST?

We become so accustomed to seeing pictures to accompany seemingly every subject under the sun that sometimes we overlook one fundamental paradox: For many situations there is, strictly speaking, no subject to shoot. There are no images.

Directors have to deal with this problem on various occasions:

■ abstract subjects that have no direct visuals (philosophical, social, spiritual concepts) (Figure 4.15);

■ general nonspecific subjects (transport, weather, humanity);

■ imaginary events (fantasy, literature, mythology);

■ historical events where no authentic illustrations exist (Figures 4.16 and 4.17);

■ upcoming events where the event has not yet happened;

■ events where shooting is not possible, is prohibited, or the subject is inaccessible;

■ events where shooting is impracticable, is dangerous, or you cannot get the optimum shots;

■ events, now over, that were not photographed at the time;

■ events where the appropriate visuals would prove too costly, would involve travel, or have copyright problems.

FIGURE 4.15

Abstract concepts can be very difficult to visualize. Cloud shots like this could be used to visualize spiritual concepts such as “heaven”.

FIGURE 4.16

Historical events are often visualized by using miniature models.

FIGURE 4.17

Some historical or imaginary events are visualized by using full-size sculptures.

So how do directors cope with these situations? The least interesting method is to have the talent stand outside of the building—where the camera was not allowed in to watch a meeting—and tell the audience what they would have seen if they had been there. Newscasts frequently use this approach when the event has already come to an end. The bank robbery, the explosion, or the fire is now over, and we can only look at the results.

Another method is to show still images or artwork of the people or places involved, utilizing explanatory commentary. This could be a good solution if the director is discussing history, such as the discovery of America or the burning of Rome. Some museum relics might even be available to show, to enliven interest, but items such as these are usually only peripheral to the main subject.

What do you like about being a producer?

First and foremost I like being able to tell the “story” of a game my way. My guiding principle when I’m producing a game is “What do I want to know about?” Also, I like being the place where the buck stops. As the producer, the format is organized your way—how you think—so you can provide complete answers quickly. And, last but not least, the challenge of getting 25 people working toward the same goal without a script (most of the time).

How do you prepare for a specific assignment as a producer?

First you have to assess what is already in place so you can decide what needs more attention (i.e. crew—are they good at what you need, do you need to get all your own crew or truck, what is on the truck and what extra do you need to get?). Next I make a format with the open, breaks, and end and then build around that. At the same time I am reading everything I can get my hands on regarding the teams/players to select interesting stories that can be supported by video recordings and/or graphic elements. I also make sure I develop strong relationships with the people I will have to interact with, mostly because they control the timing of the event. Ideally, you need to get who is controlling the timing (which also includes refs/officials) to give you a little leeway about when to restart the event after commercial breaks. But, it is important you do not ask for extra time in every break. After you get your ideal scenario set up, you then have to make a mental “Plan B” if you have technical issues and know what elements are “must haves.” The fact is, there is no substitute for experience when it comes to planning, but there are some things you have to (and will!!) learn the hard way.

FIGURE 4.18

Scott Rogers, Sports Producer.

What challenges do you have to deal with as a producer?

You have to be able to go “off plan” at any moment. You create a lot of plans/timelines of how you’re going to accomplish things, and then something technical, etc. delays you, so you have to reaccess what needs to get done now and what can wait until later or not at all. Also, you need to know what areas you need help in and delegate someone to help you with that area.

Scott Rogers has been involved in productions for the NBA and multiple Olympics, as well as local television.

Sometimes the director can show substitutes—not a picture of the actual bear that escaped from the zoo but one like it. Although you cannot show photos of next week’s parade, shots of last year’s parade may illustrate the excitement of the upcoming event.

At times, directors may not be able to illustrate the subject directly. Instead, they have to use visuals that are closely associated with it. For instance, if the director does not have photographs or drawings of a composer, he or she might be able to show shots of the composer’s native country or hometown. These shots can be used as cutaways or wherever suitable visual material does not exist for one reason or another.