CHAPTER 1

Introduction

IN THE FIELD WITH

EVENING MAGAZINE

The clock on the train platform reads 6:30 A.M. as I climb aboard the train and head for the city. The sun is not yet up and the usual bay fog hangs over the water as the train pulls out of the station. Today is a big day. In a few hours, I will be on the road with the crew from Evening Magazine, accompanying them on a remote shoot to see how things are done in the real world of video field production.

In less than 30 minutes, the train reaches the downtown station and I hop off and head for the escalator to street level. The sky has brightened considerably as I join the other morning commuters in their trek to the office. The fog has left the pavement slick, and I walk carefully as I thread my way through the downtown streets to the television station where I am scheduled to meet the field producer who has invited me along for the morning shoot. I arrive at the station at 7:30 and Mike, the producer, arrives moments later. We are not scheduled to leave until 8:30, so we duck into a restaurant across the street for a quick breakfast and some strong coffee.

Today’s shoot centers on Tom K., a 24-year-old patient at a nearby medical center. Several months ago, Tom was stricken by a virus that seriously damaged his heart. Today, his heart is working at only 15 percent of its normal capacity—the damage done by the virus is severe and irreparable. He has been on the waiting list for a heart transplant for over a month.

The story being planned by Evening Magazine focuses on Tom and on a fund-raising effort that has been organized by some of his friends. They plan to water-ski over 70 miles in the ocean to publicize Tom’s case and to solicit funds to help pay his medical bills. The story will consist of interviews with his friends, actual footage of the open-ocean waterskiing, and interviews with Tom and his doctor. The latter interviews are scheduled to be recorded today. We have a 9:30 A.M. appointment with Tom at the medical center.

Mike and I finish breakfast and walk the short block and a half back to the station and go up to the Evening Magazine offices. There’s not much activity at this time of the morning. The office occupies one corner of the floor of the building. Sections of the office have been partitioned off into small cubicle-like offices for the staff members. Two permanent rooms off to one side house the video editing equipment and serve as work stations for the two video editors. Several other offices have been assigned to the show’s producer and associate producer. Large windows face out into the city and toward the bridge across the bay.

Mike makes a few last-minute phone calls as we prepare to leave the station. Rita, the camera operator, or “shooter,” has arrived. We’re waiting for Don, the production assistant. It’s Don’s job to drive the van that will carry us to the medical center, which is about an hour’s drive south. At 8:30, there’s still no sign of Don, and Mike begins to get a bit agitated. It’s crucial that the interview be completed today, as Tom could receive the transplant at any time and the interview must be finished before the operation. Mike is getting more anxious. Finally, Don arrives.

The van is parked in the basement garage, along with other station vehicles and the employees’ cars. The sides and rear are decorated with the distinctive logo that identifies Evening Magazine. I notice an electrical extension cord trailing out a window into a wall socket. This connection to power is being used to charge up the extra batteries carried inside the van that will power the video equipment in the field.

We all pile into the van and head toward the freeway through the early morning traffic. Three bucket seats hold the driver and two regular passengers. I get to sit on a milk crate next to the sliding door. The interior of the van is paneled and carpeted, and shows the effects of plenty of wear.

Against one wall of the van is a metal cart. On it are various pieces of video equipment: a color monitor, a portable videocassette recorder (VCR), and a forest of cables. Next to this, against the same wall, is a shelf holding half a dozen or so batteries, all locked into the charging unit. Above them is a shelf of videocassettes. On the floor at the rear of the van, on a small rectangular piece of carpet, lies the camcorder. The body of the camcorder shows signs of wear. It’s scratched and dented in the places that are not covered over with decals. The Evening Magazine logo is evident. One side of the camera carries a decal of Chinese ideographs—a souvenir from a recent trip to the People’s Republic of China.

We arrive at the medical center at 9:30 A.M. and, after some negotiation with a traffic guard, manage to park the van in a red zone near the main entrance to the hospital. Mike goes inside to confirm the interview arrangements with the publicity director of the hospital, and Rita and Don begin to take equipment out of the van.

While Mike is inside, Rita and Don talk about whether today will be a two-tape or a three-tape day. The discussion is important from a planning standpoint because Don has responsibility for bringing along enough blank tape to record the interviews. If he brings only two tapes and they need a third, he will have to return to the van. However, more important than the planning considerations is what a two-tape or a three-tape day means in terms of the amount of work the crew will be required to perform. On a two-tape day, they finish work earlier than on a three-tape day.

A few minutes later, Mike returns and indicates that everything is set—the interviews can go on as planned. For the next 10 minutes or so, he gives a quick overview of the story as he sees it. He indicates that when the story is edited, it will begin with a montage sequence built out of the water-skiing shots, and then the piece will establish the main theme—that this is a benefit for Tom. Mike talks briefly about the interview segments with Tom and his doctor and mentions some specific shots he would like to have: a shot of Tom walking down a hallway to establish him and the location, shots of Tom being examined by his doctor, and so on. At 9:45, we head into the hospital. Rita carries the camcorder and a tripod. Don has a shotgun microphone and some headphones. I’m carrying a canvas bag filled with tape, cables, batteries, extra microphones, and other miscellaneous equipment, and Mike has a large soft light and stand in hand.

We set up the equipment in a hallway and Mike introduces us to Tom. He’s extremely personable and jokes about his health and his role in this program. “I’ve never been on TV before,” he deadpans. “I feel like one of Jerry’s kids.”

Between 10:00 and 10:45 A.M., the crew shoots at least six different situations with Tom. The establishing shot Mike called for is staged in the hallway. Two takes are recorded, since Tom looked at the camera and laughed in the first one. The camera is moved outside, and we record several takes of Tom entering and exiting the hospital. Then it’s back inside the building to record him as he is weighed on a scale in the hall, as his blood pressure is taken in an examining room, and as he talks with the nurse who has been supervising this activity. The entrance of the doctor into the examining room is staged and recorded, then his actions in the room are recorded without any rehearsal or guidance from the crew.

Throughout most of the taping, the crew members ask the nurse, the doctor, and Tom to go about their normal business and not pay any special attention to the camera. Rita, the camera operator, busily focuses on different elements of the activity. I notice on several occasions that she appears to reshoot something she has just shot; for example, at one point she starts a shot on a close-up of the nurse and then pans across to Tom. Apparently unhappy with the way the shot comes out, she refocuses on the nurse and repeats the shot.

At 10:45, Mike interviews Tom’s doctor in the hall outside the examination room. The light is set up, a small microphone is pinned onto the doctor, and the interview is completed in about 10 minutes. Hospital personnel freely move through the hall as the interview takes place. Once again, Don and Rita tell the hospital personnel not to worry about interfering with the crew’s work.

At 11:10, we move upstairs to the Cardiac Echo Lab, where a sonar device will be used to show what the inside of Tom’s heart looks like. The output of the device is displayed on a small television monitor. It’s eerie to watch Tom lying on the examination table and to see his heart beating on the nearby television screen. Rita records the image on the screen and also records the doctor as he traces over Tom’s chest with the sonar device. Don uses a shotgun microphone on an extendable fishpole boom to record the sound.

We move back downstairs and out to an exterior courtyard to set up for the interview with Tom. The fog has reappeared and the day is a bit gloomy. Rita finds a bench for Tom to sit on and decides she will need to use the soft light to add some brightness to the picture. We find some exterior electrical outlets to plug in the light. A large piece of blue plastic, a conversion filter, is clipped onto the front of the lighting instrument so that its light matches the color of daylight.

Don worries about the noise being generated by air conditioners protruding from the building walls into the courtyard. He conducts an audio test and decides together with Mike that the sound is acceptable. At 11:25, Tom joins us outside and Mike conducts the interview. He has some questions written down in a reporter’s notebook and asks the questions from off-camera. The interview is short—approximately 10 minutes. We thank Tom for his help and he heads back inside to wait for the day when a heart is available for transplant. We dismantle the equipment and return it to the van. Rita pops one of the videotapes into the VCR on the rack inside the van and checks the picture quality and sound on the monitor. Everything is OK. My watch reads 11:48 as we climb into the van to head back to the station. It is a two-tape day.

During the next week, two events occur that have significance to the story. First, the crew goes out in the middle of the week and shoots the ocean waterskiing footage. Unfortunately, the weather is bad and the sea is rough, and the skiers are unable to complete the planned 70-mile event. Then, one week after our interview with Tom, a compatible heart becomes available for transplantation. The operation is completed without complications. About three weeks after the interview with Tom was shot, the story is broadcast on Evening Magazine. It appears as a hopeful story of a young man’s fight to win back the life that once hung so precariously in the balance.

The kind of production typified by Evening Magazine represents an approach that has become one of the dominant modes of video production. Shooting with a single camcorder, which combines a high-quality video camera and video recorder into one easily carried unit, and a relatively small crew by traditional television standards, organizations like Evening Magazine have revolutionized the concept of video production. Increasingly, video production is field production; it takes place in the outside world, rather than in a studio inside a television station or video production facility (see Figure 1.1). In addition to magazine-style stories, on-location news productions, documentaries, and reality programs are typical examples of video produced in the field.

FIGURE 1.1 Television News Photographers Equipped with Professional Camcorders Cover the Arrival of the President

This type of production depends on reliable, portable video production equipment and on the ability of skilled production personnel to use it. The focus of this book is on such single-camera video field production—on the equipment that makes it possible and on the production techniques and strategies that can be used to create effective messages through the use of this technology.

THE EVOLUTION OF VIDEO

PRODUCTION TECHNOLOGY

When television was demonstrated to the U.S. public at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York, it thrilled those who saw it. The display was impressive: Technicians, cameras, lights, and the instantaneous transmission of a televised image and sound were all part of the event. Not only was the demonstration impressive but so was the equipment, particularly its size. Television cameras and television lights were very large and complicated pieces of equipment. Indeed, during the first several decades of its existence, television production was characterized by the large size of the equipment needed to produce televised images.

In the early days of television (and even today for large-scale remote sports productions), a remote production—one staged outside a studio—was an incredibly complicated event involving scores of technicians and an armada of equipment. When one went on a remote, essentially one took the television studio along and set it up at the remote location. The same equipment used in the studio was often rolled into a truck and used for a remote broadcast.

For many years, only two alternatives were available to a producer who wished to incorporate remote material into a production. The first alternative was a live electronic remote broadcast, with the problems inherent in transporting huge amounts of television equipment to the remote location. The other possibility was to cover the event on film. Until the mid-1970s, film was used extensively in television for news and documentary production, largely because of the portability of 16mm film equipment. However, a revolution was brewing in television that would change remote production. It started quietly enough, but by the 1980s, the use of film for remote television production was largely replaced by the use of portable video equipment. Table 1.1 chronicles some of the highlights in the development of video technology.

Portable video systems have been significantly refined in the four decades since their introduction. Portable systems composed of a separate camera tethered by cable to a portable VCR have been replaced by one-piece camcorders, and video editing systems have become smaller, less expensive, and more precise. Originally, the equipment used in video field production and editing was based upon conventional analog signal processing and recording. Today, however, a whole new generation of digital camcorders and nonlinear digital editing systems is poised to take over as the current analog systems wear out and are replaced and as the U.S. broadcast system converts to a new, federally mandated digital standard.

PRODUCTION USES OF

PORTABLE VIDEO EQUIPMENT

It is important to note that video production no longer is an expensive, labor-intensive activity available only to federally licensed television broadcasters. As a result of the portability and accessibility of this new technology, video has found a host of new uses. Portable video is increasingly being used for personal expression, for independent production, in educational institutions and corporations, and in the arena of broadcast and cable television.

Personal Video

Because of its relatively low cost, portable video equipment has made video accessible to individuals in much greater numbers than ever before. VCRs and/or DVD players can be found in almost 90 percent of all U.S. homes and camcorders in about half. VCRs, camcorders, DVD players, and digital disk-based personal video recorders are among the most popular consumer electronics items introduced in recent years.

The popularity of digital disk-based personal video recorders has given rise to a relatively new phrase: Instead of saying that they are going to record a program, DVR users often say instead that they are going to “TIVO it.” This is a reference to the brand name TIVO DVR, which was one of the first on the market and continues to have one of the most identifiable brand names of all DVRs.

Personal uses of portable video equipment vary. Some people buy video recorders for use primarily in their home entertainment systems. These machines are used to record programs that have been broadcast or cablecast, or they are used to play back owned or rented videocassettes or DVDs. A growing segment of users have purchased portable video camcorders in addition to their home video recorders. These low-cost camcorders have the advantage of producing electronic recordings that are available for immediate playback. They are used extensively to record family events such as birthdays, special parties, and weddings. Sports enthusiasts use them to record and then criticize their own sports performances, such as golf swings, swimming strokes, and tennis serves. In addition, these camcorders are convenient for making visual and sound messages to send to friends or relatives who live far away (see Figure 1.2).

Independent Video Production

Independent video production refers to those organizations and individuals who use video to make their own programs or who make their production skills and facilities available to others who want to produce and distribute messages via video. A large group of independents have used video to produce television documentaries. Almost any large or medium-sized community contains individuals who are working on video documentaries that focus on various community-oriented social, economic, and political problems. These independents may have a number of goals in mind. Some may try to gain access to their local cable company or television station with their finished program, whereas others may try to distribute their material regionally or nationally. Whatever the distribution aim, the availability of relatively inexpensive equipment and facilities provides an opportunity for video production independents to express alternative viewpoints on community and national problems.

Many independent producers produce video for clients. These may range from producing a video for a couple who want to record their wedding, to producing video for a small company that does not have its own video production facility but that wants a video that introduces a new product to a client or trains employees in new sales techniques, new methods of product maintenance, and so on.

Video Art

Independent artists have been using video for some time. Video has become popular as a medium for artistic expression, and numerous video experimenters have gained access to the medium through the use of portable equipment. Whether the artistic statement is dramatic or experimental, whether it involves the manipulation of content or formal properties of the medium (such as lighting, editing, or sound), access to the medium has been facilitated by the introduction and use of this equipment.

Educational Uses

In the past decade, numerous educational institutions have turned to video, primarily for nonbroadcast, in-house uses. For example, video is often used in schools as a supplement to instruction. Indeed, some actual instruction may be done via televised lectures live or previously recorded. Speeches in public-speaking classes are recorded and then played back for a critique by the instructor or class. Teacher-training programs often videotape student teachers to provide a record of their classroom performance. Colleges and universities with programs in the broadcast or electronic media most frequently use portable video equipment in their laboratories and cable television facilities.

Medical Video

Many hospitals have their own video staffs and put video to a variety of uses. It is used for the distribution of in-house information and for instruction in new medical techniques as a part of an ongoing program of continuing education. It is also sometimes used to provide information to patients on various health problems and their treatment. Institutions involved in providing therapeutic treatment such as counseling or other forms of therapy to patients with speech defects or mental or emotional problems often use video as part of therapy or to record therapy sessions.

Legal Video

Video is finding increasing use in legal settings. The broadcast of President Bill Clinton’s August 17, 1998, videotaped grand jury testimony brought worldwide attention to this specialized use of video technology.

Professional guidelines have been established in most states for the recording of legal depositions. Legal video producers are in demand to produce video reenactments of accidents and crime scenes as well as to design effective video presentations of critical exhibits of evidence, such as photographs, maps, time lines, and so on, for use in courtroom presentations.

Corporate Video

Many large corporations use video to distribute electronic corporate newsletters to their employees, particularly if corporate offices are widely distributed. In-house training or staff development is another common use, as is video for use at the point of sale. You have probably seen product demonstrations being played on video monitors in department stores.

Government Uses

Local, county, state, and federal government agencies also are significant users of video. Many government agencies produce video to inform their constituents of new programs, policies, regulations, or accomplishments (see Figure 1.3). In some cases, these programs may be cablecast or broadcast via local media outlets.

Public Access

Similarly, portable video has proved invaluable for local media access groups. Many cable systems operate public access centers in which studio or remote equipment is available to community members. A provision for community access may be included in the franchise agreement for the cable company that operates in the town or city where you live.

Broadcast,Cable,and Satellite Television

The move toward the miniaturization of professional-quality equipment is a strong and continuous process. Broadcast and cable satellite television uses of portable video equipment have centered in two areas: electronic news gathering (ENG) and electronic field production (EFP). It was in the area of ENG that portable video equipment first made a significant impact in broadcasting. Prior to its introduction, broadcasters relied on film for stories that took place in the field, or on the placement of live remote television cameras. The difficulty with film recording was the time delay involved in returning the film to the station or network and in processing and editing the film.

The introduction of lightweight, portable video recording systems changed the face of television news. Most local television stations, as well as the major broadcast networks, made the transition from film to portable video for electronic news gathering in the mid-1970s. The creation of 24-hour cable news channels like CNN and MSNBC was made possible by portable video production equipment and the microwave and satellite transmission links that are used to instantaneously transmit pictures and sound of news events as they occur anywhere in the world.

Similarly, the existence of portable broadcast-quality video recorders and cameras made possible the growth of EFP. Before the introduction of this equipment, much local television programming had been based in the studio or shot on film by those few stations with a commitment to remote production. The introduction of portable professional-quality equipment made it much easier for producers to get out of the studio. Nationally syndicated television magazine feature programs such as Hard Copy, A Current Affair, and Entertainment Tonight rely on remote production crews using portable video camcorders. Programs such as 48 Hours, 60 Minutes, Dateline, and 20/20 are examples of network television programs that make extensive use of portable video technology. A host of “reality-based” programs such as Survivor, MTV’s Real World, Cops, and America’s Most Wanted rely as well on portable video technology for field production and editing. These programs reflect the fact that quality production no longer depends on studio-based equipment. Portable video production equipment has proved itself to be a reliable and cost-effective part of the professional video production process.

FIGURE 1.4 Multimedia Incorporates Video and Sound

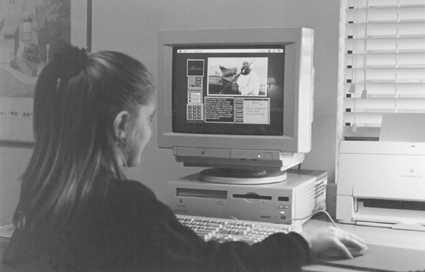

Multimedia Production and Video

on the World Wide Web

Not all video is destined to be viewed on a conventional television set. With the increasing popularity of personal computers for the home, there is a growing demand for the skills professional video producers can bring to multimedia production. Multimedia programs incorporate animation, sound, text, illustrations, and video. Frequently produced for distribution on CD-ROMs (compact disc read-only memory) or DVDs (digital versatile discs) or via the Internet, these programs are viewed on a computer screen and allow the viewer to interact with the program material (see Figure 1.4).

In addition, viewers have increasing access to video that is distributed via the Internet from a wide variety of World Wide Web (WWW) sites. Although the limited bandwidth of the typical telephone modem link to the Internet does not yet allow for full-screen, full-motion video displays on home computer screens, new developments in video compression and transmission technologies, and more powerful home computers, will continue to improve the quality of video and sound distributed through the Internet. As broadband distribution technologies such as DSL (digital subscriber line), cable television modems, and wireless broadband are adopted by more home computer users, the home computer or the home digital television receiver connected to the Internet will become the point of reception for new services such as interactive television as well as video programs that are webcast, that is, transmitted directly over the Internet from the program’s creator to one or more receivers.1

CAMERA EQUIPMENT

QUALITY AND TARGET MARKETS

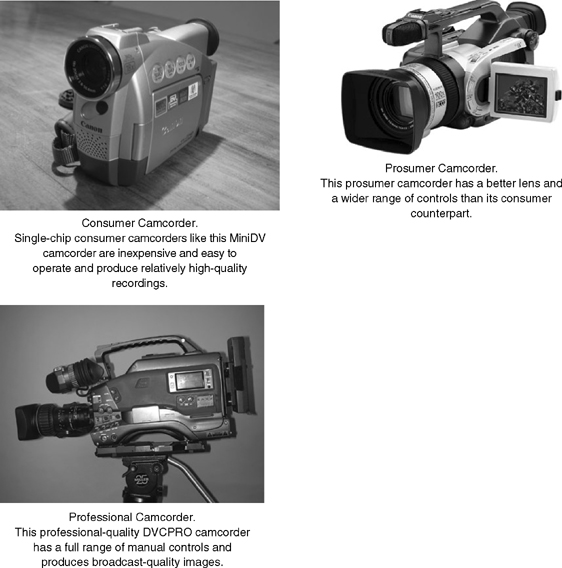

Video equipment makers produce a wide range of equipment that is designed to meet the needs of consumer users, video enthusiasts, and production professionals. (See Figure 1.5.) Video equipment varies greatly in terms of features, quality, and cost.

Consumer and Prosumer Equipment

At the low end of the scale is consumer-level equipment, which is marketed to home video users for their personal use. Consumer camcorders can readily be bought for less than $500, and the quality of the images they produce and record is remarkable given their relatively low cost. This type of equipment tends not to be very durable and many of the basic camera control functions have been automated to eliminate operator errors.

Prosumer equipment is a step up in cost, quality, and features from consumer equipment, but this equipment generally is not used in a professional environment. A serviceable prosumer camcorder might cost in the neighborhood of $1,000 to $3,000 and provide the operator with a bit more durable quality and more controls that feature manual as well as automatic settings.

Professional/Broadcast Equipment

At the high end of the scale is equipment designed for the professional/broadcast market. This equipment is the most rugged and contains a wider set of controls for the professional operator. Prices for professional cameras and camcorders vary widely depending on how they are to be used. High-quality ENG camcorders can easily cost between $10,000 and $20,000; high-end cameras and camcorders designed for High Definition Television production may cost up to $100,000.

It is generally important to match the quality level of production equipment to the situation at hand. Most broadcast outlets expect programs to meet technical standards that are more easily achieved with professional-quality equipment than with consumer- or prosumer-level equipment.

VIDEO AS A MEDIUM

OF COMMUNICATION

Video is both a medium of communication and a type of technology. The successful producer must understand not only the components and operation of the technology of video communication but also the elements of the process of communication via video. As we view the process of video field production, five elements characterize this particular communication situation:

1. The unique elements of the production organization (source)

2. The fundamental importance of message design

3. The importance of the video medium as a channel of communication

4. The particular nature of the audience

5. Audience feedback to the program producer

Figure 1.6 graphically displays this communication process.

Production Organization

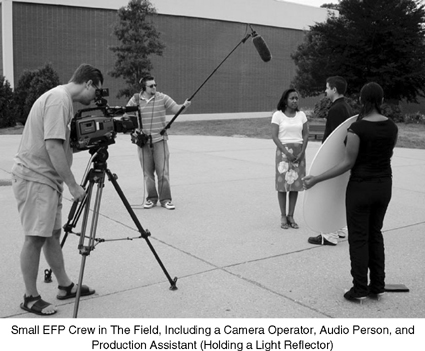

The video field production group is often significantly smaller than the studio production organization. Typically, the principal roles involved in producing single-camera remote productions are the producer, who is responsible for the overall organization of a production and for delegating responsibility to the other members of the production team; the camera operator, or videographer (sometimes called the shooter), who is responsible for the visual treatment of the subject matter as well as for the physical operation of the camera; the production assistant, who is responsible for monitoring audio, helping to set up the lights, and providing other general production support; and the video editor, who is responsible for executing the producer’s vision in the process of postproduction editing. The editor has primary responsibility for physically performing the edits, and, depending on the role of the producer, the editor may have much or little responsibility for actually making editing decisions. In many cases, work roles overlap. An entire production may be produced by two or three people, with each assuming several responsibilities during the production.

The nature of single-camera field production and the small production crew it involves often create a sense of excitement and responsibility that studio productions lack. Each person’s contribution counts. There is often intense involvement by the crew on the production, and those involved exercise greater control over the final product than do their counterparts in studio production. The challenge of recording in the field, the excitement of instantly playing back images that were recorded only minutes ago, and the intense involvement demanded by the editing process all characterize video field production (see Table 1.2).

FIGURE 1.6 Communication Process via Television and Video

Message Design

Message design is a critical part of the telecommunication process. Ironically, one of the first elements that should be considered is the desired effect of the message. Who is to do what with this information? Because the goal of most commercial television programming is to maximize the size of the viewing audience at a given time, many program producers and station program directors desire to design and distribute entertaining and informative programs that will appeal to the largest cross-section of the general viewing audience. Success is typically measured in terms of program ratings, which provide an estimate of the size of the audience and determine how much money advertisers can be charged to place their commercials on the air.

Producers of educational and industrial video programs frequently begin the design stage of their productions by thinking in terms of a list of specific objectives—things they hope the audience will be able to understand or do after viewing a particular program. Whether you are producing a program designed to teach language or computational skills to children or new safety procedures to employees in your manufacturing facility, you must have a clear understanding of the effects you expect your program to have on the viewers before you begin to produce it. Naturally, you will also need to consider your target audience. A program aimed at children will be approached differently from one aimed at adults, even if the subject matter is similar. Message design is therefore concerned with the basic idea, which involves the choice of subject; a decision about how that subject will be treated as it is presented through the video medium; and an understanding of how to control the treatment of the subject to achieve maximum impact on the target audience.

| Studio | Field | |

| Number of cameras | Multiple cameras (usually 2 or 3) | Single camera |

| Size of crew | Large (often 8 or more) Producer Director Audio Camera operators (2 or 3) Floor director Technical director VTR operator |

Small (usually 2 or 3) Producer Camera operator Production assistant |

| Recording method | Usually live or live on tape; a complete program or large segments | Individual segments or shots to be edited or inserted into a larger program |

| Amount of control over environment | Controlled studio Studio lighting Sound (acoustics) controlled Assured source of power Available technical support staff |

Uncontrolled remote location Available light Ambient, location sound Must provide own power No technical support |

| Type of script | Usually fully or semiscripted | May be fully scripted, often semiscripted |

The Video Medium

Until relatively recently, television and video have been characterized by the small size of the viewing screen. Traditional cathode ray tube (CRT) television/video displays typically range in size from 13 inches in diameter to a maximum size of approximately 36 inches. This is very small in comparison to theatrical motion picture screen displays. However, large flat screen video displays are becoming increasingly popular, particularly in screen sizes of 42 inches and greater. (As this book goes to press, the largest flat screen video display available is 102 inches in diagonal.)

The small screen lends itself well to the use of close-up shots; wider screen displays provide the ability to focus on wide shots that emphasize the landscape over close-up detail. Nevertheless, the close-up shot continues to play a central role in most programs produced for television and video.

The audience has learned to expect close-ups and reaction shots, and the successful producer will give the audience what it expects with respect to these conventions. Close-ups provide the magnification often necessary for small-screen use. Magnification, a key to visibility, is central to most video production. Close-ups are also important because they are a means of focusing audience attention on a specific detail or relationship by eliminating all other parts of the picture.

Reaction shots are important to messages designed to persuade or to generate an emotional response. The use of reaction shots evolved as media practitioners learned that the effect of a statement or action is determined by the receiver, not the sender. The quick cut to the face of a person listening to a speaker reveals how the speech is being received, whether it is being accepted or rejected. In seeing how this person reacts, the audience is told how to react in turn.

The Audience

The dictum “know your audience” is just as important for video producers as it is for public speakers. Producers of corporate and instructional video always include a description of the characteristics of the program’s target audience in their preproduction planning material and use their knowledge of the target audience to guide production decisions at each step of the production process. Even though broadcast and cable television are often thought of as forms of mass communication, the successful video producer realizes that communication takes place between the message and an individual in the audience. Even though someone may be part of a very large audience, for a message or program to be effective, it must communicate individually to each person in the audience. This is no easy task, given the variations that may exist among different audience members.

Feedback

Feedback is that part of the communication process in which audience responses to the production are transmitted to the producers. The nature and extent of feedback are related to the type of production and the way in which it is distributed to and received by the audience. In commercial broadcast and cable television, program ratings—a measure of the size of the audience—provide one indication of the audience response to a program. E-mail, telephone calls, and letters from audience members to stations and networks are also an important part of the feedback process. For the home video producer, feedback might take the form of comments by family members on the quality of the videotape documenting a family celebration. Feedback is extremely useful to the video producer because it provides important information about the audience’s response to the program or videotape—information that the producer needs to have in order to make subsequent productions more effective.

PRINCIPAL ELEMENTS

INVOLVED IN VIDEO PRODUCTION

Technical Factors and Aesthetic Factors

Video field production combines an understanding of the technical factors of production with the aesthetic factors of production. Technical factors relate to developing an operational understanding of the way in which equipment functions. To work successfully with portable video equipment, you must understand how the equipment works. This does not mean that you need to be an engineer or understand all of the electronic and physical principles that govern the operations of the equipment. What it does mean is that you must have an understanding of the way in which the system operates—the way in which different technical elements interrelate and the way in which you can control the technical components of production. It also means that you need to have a basic understanding of what the video signal is and how it can be controlled. All video equipment operates on similar principles; this book stresses fundamental underlying principles of operation. Because underlying operational principles vary little among brands of equipment, you should have little difficulty in adapting the general principles discussed here to the specific requirements of a particular system.

Many handbooks on video production are nothing more than manuals of equipment operation. However, this text takes the position that one must know not only how to manipulate the equipment but also how to manipulate the medium in which one is working: video. This brings us to the area of media aesthetics. Aesthetic factors, throughout this text, refer to production variables and the ways in which they can be manipulated to affect audience response to the video message.2

The process of video field production is a combination of technical factors and aesthetic factors. Whether you are engaged in video production for personal, artistic, educational, or broadcast uses, the requirements of the technology and the medium must be considered. The fundamentals of production and the production processes discussed in this book will be helpful to you, no matter what type of video production you are engaged in.

Creative Problem Solving

If there is one phrase that expresses what is at the center of video field production, it is creative problem solving. Communication via video means that the producer/writer/director must understand the medium and how to use it. Finding the appropriate techniques to effectively express the idea and content of a program presents problems that must be solved creatively.

Video field production also presents a unique set of logistical problems. No two days of shooting in the field are ever quite the same, because no two locations are ever the same. The ability to deal with the range of problems encountered on location is the mark of the successful field production person.

Finally, video field production presents a set of unique technical problems. People involved in field production simply must know more about the technical side of video production than must their studio counterparts. All manner of technical problems arise in the field, and field producers must be able to anticipate and avoid them or correct them when they arise.

Teamwork and Control

Teamwork. Video production is a group activity. No one individual can do everything that needs to be done on a production. Successful producers and crew members need to remember at all times that they are part of a production team focused on a common goal—the creation of an effective video production (see Figure 1.7). To achieve this goal, all team members should have a clear idea of their responsibilities, and they should strive to communicate clearly with each other at all times.

Control. One of the most important challenges in video field production is to take control of the location in order to maximize the chances of completing a successful production. Unlike the studio video producer, who works in an environment with controlled lighting, acoustics, and sound, the video field producer works in remote locations where these elements may vary greatly from location to location and from one time of day to another. The ability to effectively control these elements is an essential characteristic of the effective field producer.

NOTE

1. See Chapter 13, Video on the Web, in Compesi, Ronald J. and Gomez, Jaime S., Introduction to Video Production: Studio, Field and Beyond, Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2006.

2. For a full discussion of media aesthetics, see Zettl, Herbert, Sight Sound Motion: Applied Media Aesthetics, 4th ed., Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 2005; and Douglass, John S. and Harnden, Glenn P., The Art of Technique: An Aesthetic Approach to Film and Video Production, Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 1996.