CHAPTER 2

Preproduction and

Production Planning

Without a doubt, the key to success in field production lies in adequate production planning. The remote producer is at the mercy of the location and the people in the production and does not have the same kind of controlled situation as the studio video producer. Therefore, it is imperative that all elements of the production be as carefully planned as possible. This is not to suggest that such planning ensures that the production will go off without a hitch. If there is one thing that can be guaranteed in field production, it is that the unexpected will happen—and you must be able to cope with it.

Nevertheless, producers who carefully plan out the course of their productions undoubtedly have greater success in the field than do those who do not plan. In fact, the planning part of the production often involves more time and energy than does the actual production time in the field.

STAGES AND TYPES

OF PRODUCTION

Three Stages of Production

All productions can be broken down into three stages: preproduction, production, and postproduction. The preproduction stage is crucial to a production’s success because it is in this stage that the initial idea for the subject is developed and the production mechanism put into motion. Thorough preproduction planning ensures that the actual production phase goes smoothly. The production phase of a field production is the actual shooting time for the program. Finally, the postproduction phase involves the editing and packaging of the production. Once again, anticipating and solving problems through thorough planning in the preproduction and production stages will make the postproduction process easier.

When producers encounter unanticipated problems in the field, they may be inclined to say, “Don’t worry, we’ll fix it in postproduction.” While this is sometimes possible, more often than not major problems that are not corrected in preproduction or production will haunt a production. Some problems can be solved, others cannot. The place to anticipate and solve problems is in preproduction, not postproduction.

Adequate planning is an important part of all three production stages. A comprehensive map of the program plan must be communicated clearly to all members of the production group for the overall program design and production to be executed efficiently and smoothly. This is in large part accomplished through production planning. All major decisions about a production should be made on paper before the camera is uncapped and the tape rolled.

Independent versus

Client-Based Production

The production planning process is influenced by the nature of the production. An independent production is one in which the producer is responsible for the development of the program idea and does not have to report to another agency or individual for consultation or approval. This type of production operates somewhat differently from a client-based production—one in which the producer has been hired to carry out someone else’s program idea.

Video producers find themselves in many different production situations. In the commercial arena, the producer most often executes production ideas developed by others. In the area of independent documentary production, the producer most often develops an idea and carries it through the production process. However, in many cases, the producer must report to a grant-giving agency to obtain the funds necessary for the production. The in-house corporate video producer may have to report to an executive producer or department head to win approval for production projects but may then be given significant autonomy to develop and execute the production idea.

PREPRODUCTION

PLANNING

Getting and Developing a Program Idea

Whether a video program is developed to communicate an idea about a political issue, to attempt to persuade the audience to buy a particular brand of deodorant, to convey information about changes in corporate policy to employees, or to entertain through the presentation of a dramatic, comedic, or musical extravaganza, the program idea is at the heart of the production. No program can proceed without a basic idea governing its organization and production. Both the media experimentalist, who breaks narrative and aesthetic conventions of media structure in order to challenge the audience to focus on new relations between visual and aural images, and the instructional video producer, who uses the medium to clearly and unambiguously teach a subject to a target audience, make a series of initial decisions about the design of their respective programs.

In the early stages of program development, the program idea contains at least several components. Central to the idea is the concept of the program’s subject. What does the program producer want to communicate? Evaluating the target audience gives the producer important information about the medium best suited for transmitting the idea, and the way in which the subject can best be treated in that medium to communicate the program idea effectively to the audience. So, in the initial planning stages of a program, we need to consider the concerns that were raised in the first chapter of this book: The idea for a program can be moved to effective actualization only through thorough consideration of the elements of subject, medium, treatment, and audience.

For the independent producer or the student who is required to complete a program for a video production course, getting the idea may be the hardest part of the production process. For the in-house producer or educational media specialist, ideas may be generated by resource people with expertise in particular content areas. The producer’s role, then, is to adapt the content to the particular requirements of the medium and audience by applying the proper treatment to its development.

Program Conceptualization

and Design

No matter what the source of the idea for a program or program segment, the video field producer should follow a method for the development and execution of the program idea. At least four areas should be addressed in the initial stages of program design and conceptualization: subject, treatment, visual potential, and feasibility.

Subject. Preliminary planning should consider the subject from at least two perspectives: content and structure. Analysis of the content of the subject identifies the important information to be conveyed in the piece—what is to be communicated and why this information is important and/or appealing to the audience.

Information about the subject and audience can be gathered by conducting basic research on the subject and audience. For many years, U.S. broadcasters were required to ascertain the needs of their communities through systematic research and interviews with community leaders and then to broadcast programming designed to meet those needs. The staffs of many ongoing program series include one or more researchers whose job it is to identify subjects of interest to their audiences. In news operations, assignment editors determine which of the day’s stories have the greatest importance and/or potential interest to the viewing audience and then assign their production to the various ENG production teams.

Initial program planning should also consider the structure of the presentation. At the very least, you should make some preliminary plans as to the organization of the material. Aristotle’s observation that all drama contains a beginning, a middle, and an end is just as useful to video producers as it is to theatrical dramatists. Indeed, concepts of dramatic structure are as indispensable to the producers of television news, documentaries, and commercials as they are to the producers of televised drama. Story structure is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 9.

Program Format/Treatment of the Subject. Once the subject has been identified, a decision needs to be made about how the program idea will be presented. Not only does a program format have to be identified but also decisions need to be made about the way in which the subject will be treated within the chosen format. For example, concern about the negative consequences of tobacco use might lead one producer to produce a documentary on the medical consequences of smoking, while another producer might develop a campaign of public service announcements (PSAs) to be distributed to local television stations.

The documentary approach can rely on the testimony of experts, focus on victims or survivors of smoking-related illnesses, or combine the two. The public service announcements can focus on one issue or many, perhaps using so-called commercial production techniques.

Visual Potential. While developing a production idea, some thought must be given to the visual potential of the subject. In many ways, this is a two-edged sword. Concern with those subjects having greater visual potential over those with less visual potential has led to some serious, justified criticism of television. Subjects with more visual potential often seem to be those that receive coverage, while those with less visual potential are ignored.

In evaluating the visual potential of the subject, the producer should consider not only whether one subject has more visual potential than another but also how the visual potential of any subject can be maximized. On the surface, a discussion of the failing economy might seem to have less visual potential than a magazine segment on trained chimpanzees who parachute from airplanes on skis and slalom down a mountain ski course. But this may be only because the producer has not thought out the visual potential of the piece on economics. At the very least, a discussion of economic theory could be supplemented with visual material on the subject: computer-generated graphics or perhaps three-dimensional models to convey information about various concepts or to support the discussion. Interviews or profiles of real people suffering the consequences of the economic problems can be integrated into the program. For example, a discussion of rising interest rates need not focus only on the statements of a mortgage banker sitting in an office. It might also include shots of construction sites and lumber mills to provide external visual information about the issues being discussed.

Even if additional visual material is not going to be used in the story, the visual potential of the basic interview with the banker should be considered. The interview location, camera position, shot selection, and lighting can all be manipulated to maximize the visual potential of the interview.

Feasibility. No program proposal is worth developing if it is not feasible. A documentary based on the lifestyle of the members of the local Zen Buddhist bakery might seem intriguing, but the likelihood of ever producing such a piece is slim if the local Buddhists are cloistered, have taken a vow of silence, refuse to allow interviews, and prohibit cameras from entering their premises. Preliminary decisions about the feasibility of the program should focus on the field producer’s ability to get access to the subject as well as on the availability of resources to support the production. Production resources include financial support (an adequate budget to pay for the production), personnel (paid or unpaid production personnel to execute the production), and equipment and facilities.

Formal Program Proposal

and Shooting Schedule

Once the preproduction planning has been completed, you will be able to develop a formal program proposal. The amount of detail contained in the proposal will vary, depending on your production situation. A proposal for submittal to an agency as part of an application for a development or production grant will be more detailed than one developed for an in-house production or an independent production not dependent on outside funds. Depending on your particular situation, your formal program proposal will contain some combination (and perhaps all) of the following elements.

Treatment. A narrative description of the idea for the project should be presented to convey the essential idea behind the project, as well as its importance and need. An example of a treatment for a video documentary is presented in Appendix Five.

Outline of Major Elements. This section should present an outline of the major elements of the program. If your proposal is for an entertainment or documentary program, this section identifies the program’s most important parts. If you are producing an educational program, this section will outline your major goals or objectives, perhaps in the form of a list of what is to be learned from the program.

List of Locations and Setups. A list of locations and setups is extremely important because it will give you an idea of how you will need to budget your production time. A location is a general area where shooting will take place, whereas the setup describes specific shooting areas at the more general location. For example, one might schedule a location shoot at the local airport. At that location, specific setups might be needed at the ticket area, baggage area, and maintenance area.

Outline of Proposed Shooting Schedule. The shooting schedule outline presents a realistic estimate of how each production day will be spent. The outline should include a breakdown of the amount of time each segment is expected to take to shoot, as well as the more mundane elements such as time for travel, equipment setup, and breaks for the crew.

Figure 2.1 presents a proposal for a remote segment from the PBS series Over Easy. Notice how the four elements just listed are developed and presented in this proposal.

Comments on Technical Feasibility. You should address any questions about access to the location, crowd control, or access to power and/or adequate light. If a remote survey has been completed, this can provide answers to the most important questions about the use of the proposed remote locations.

Script. A script is an important part of any production. If your program will be completely scripted, a copy of the script or an excerpt from it should be included in the proposal. If your program is a documentary or is based on interviews, you will not have a complete script. Instead, present an outline of the major components of the program. (Scripts are discussed in greater detail later in this chapter.)

Evaluation. Programs produced with particular goals in mind need to be evaluated for effectiveness. The proposal form, therefore, should contain a description of the method that you plan to use to evaluate the effectiveness of the program.

There are two types of evaluations that are performed in video productions: formative and summative.

Formative evaluation is an assessment of the project that is conducted while the program is being produced. From the initial conceptualization of the video and throughout the production process, there is the need to constantly evaluate what is being done to ensure the objectives of your program are being met. Formative evaluation should permeate the whole production process to provide continuous feedback that you can use to adjust the production as changing circumstances or new ideas come into play.

There are many ways to perform formative evaluation, but the most common are: (a) commentaries by peers, colleagues, or friends; (b) focus groups with members of the intended target audience, experts on the subject, or other video producers; (c) screenings of the program to observe viewers’ reactions; (d) questionnaires; and (e) interviews.

Summative evaluation refers to evaluation done after the production is completed. A producer needs to know if the program met the goals established for the program. For an educational program, summative evaluation may involve measuring what viewers learned from the program. Commercial producers might look at the impact the commercial has had on product sales. Entertainment producers might look at the program’s ratings or critical reviews of the program.

Budget. Many program proposals include an estimate of the budget for the program. The budget should be a realistic estimate of all the costs associated with the production. Video producers find themselves in a variety of production situations with respect to budgeting. For example, a home video producer or a student in a university production course may find that the only cost associated with a production is the cost of videotape. The independent producer, on the other hand, may have to rent a considerable amount of equipment for the field shoot, and facilities for postproduction editing. The field producer working within a television station might not have any responsibility at all for developing budgets, since all production costs may be carried as part of the normal operating expenses of the station.

How, then, does one go about developing a budget? Because the budget should present a realistic assessment of the costs associated with the production, developing the budget depends on your particular production situation. The cost of producing an hour of prime-time dramatic television for distribution on one of the commercial networks may exceed $1 million. Although only a few video producers work in this budget range, even nonbroadcast productions produced to professional specifications may be relatively expensive. For example, professionally produced programs for corporate and institutional clients may cost from $1,000 to $2,000 per minute of finished program.

Many producers of small-scale productions find that their budget needs are significantly more modest than those just described. A 30-minute independent documentary, a video documenting the accomplishments of a community organization, or an edited video of a wedding ceremony can often be produced on a shoestring budget and delivered for a few thousand dollars or less.

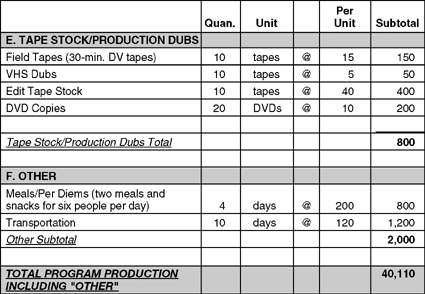

Figure 2.2 shows the actual production costs for a small-scale production that resulted in the completion of a five-minute music video, produced with a professional DVCPRO camcorder and edited on a digital nonlinear editing system. The principal production equipment (camcorder, editing system, lights, microphones, etc.) was supplied by the university department in which the student who produced the program was enrolled. Members of the production crew were not paid for their time, thereby eliminating personnel expenses completely. Additional expenses included videotape and an external computer hard drive, rental charges for a music recording studio, and miscellaneous supplies. The total cost of the production was just under $2,000.

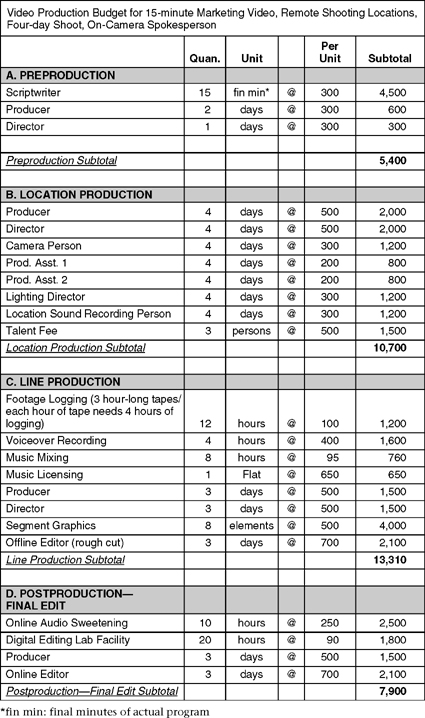

Figure 2.3 shows a budget for a 15-minute marketing video produced in the San Francisco Bay area. Unlike the music video production, all production personnel involved in this production were paid at the prevailing rates in the area. The total production costs were $43,210, slightly less than $1,500 per minute of finished program.

Scripts

Because the types of programs that video field producers work with are quite varied, a number of different script formats and scripting strategies are used.

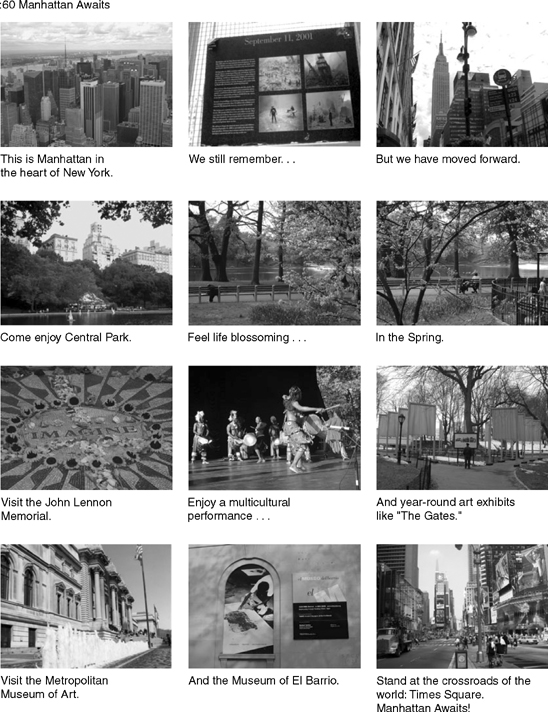

Story Outline Script. In most electronic news gathering (ENG) situations, and in many other production situations as well (such as television magazine segments), a formal script probably will not be developed. Because time is of the essence in such productions, it is more likely that a story outline will be developed. The story outline script is a list of the major elements that will be used in the story. Usually, it specifies the locations to be used, the essential visual material to be recorded at the various locations, and the subjects of any interview segments. Occasionally, specific recommendations for shots, particularly transition shots and opening or closing shots, are specified (see Figure 2.4).

Sometimes the story outline is not written but is instead presented orally by the segment producer to the production crew. This type of production planning (or lack of it) is not recommended for the beginning producer. Professional crews are able to utilize this shorthand method of production planning principally because they are used to working together as a team and, most importantly, because they understand the conventions of television. That is, they all know what they need to get onto videotape in order to gather enough material for the story to hold together. Without even having a script, the camera operator knows what needs to be shot and may even stage multiple takes of a particular shot or sequence that will be important to the overall story. The producer may have a list of questions or an outline of subject matter to be treated in an interview.

Music Video Production Budget

Shooting Days : 6

Length : 04:52

| Qty | Unit | Cost | Total | |

| PREPRODUCTION | ||||

| Story development | 1 | 15 | 15 | |

| Music production (food & rent studio) | 130 | 130 | ||

| Audio (dat + cass + dubs) | 1 | 40 | 40 | |

| Location scouting (pictures + gas + permission) | 50 | 50 | ||

| Subtotal | 235 | |||

| PRODUCTION | ||||

| Talent | 0 | |||

| Crew | 0 | |||

| Production expenses | ||||

| Catering | 1 | 110 | 110 | |

| Makeup | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Props & Costumes | 1 | 50 | 50 | |

| Miscellaneous | 1 | 100 | 100 | |

| Set | 1 | 249 | 249 | |

| Location/gas | 1 | 50 | 50 | |

| Field Equipment | ||||

| DVCPRO Camcorder | 6 | day | 0 | 0 |

| Camera supplies | 2 | day | 0 | 0 |

| Lighting | 6 | day | 0 | 0 |

| Playback VCR | 3 | day | 0 | 0 |

| Tapes | ||||

| DVCPRO (60 min.) | 16 | 20 | 320 | |

| Subtotal | 879 | |||

| POSTPRODUCTION | ||||

| Videotape | 2 | 20 | 40 | |

| 250 GB hard drive | 1 | 200 | 200 | |

| Final Editing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other expenses | 1 | 50 | 50 | |

| Video dubs | 50 | 1.5 | 75 | |

| DVDs | 50 | 10 | 500 | |

| Subtotal | 865 | |||

| TOTAL | 1979 |

FIGURE 2.2 Small-Scale Production Budget

In the ENG situation, an on-camera stand-up introduction and close are usually recorded on location. In other kinds of electronic field productions (EFPs), such introductory and summary statements are most often added to the production later as a voice-over by the principal talent. In both types of productions, the video editor has responsibility for viewing the tape and making the primary editorial decisions about which shots to use, what order to use them in, and how much of the primary interview material to include in the segment. Figure 2.4 presents an example of a story outline written by a field producer for the video editor.

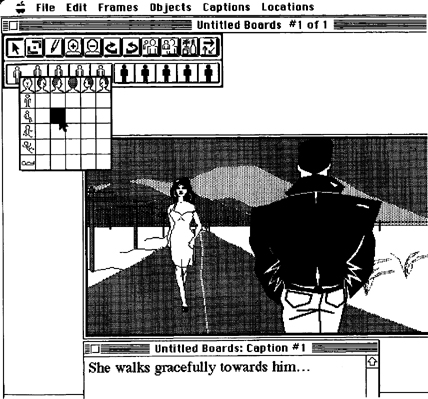

Storyboard. A storyboard is a visualization of the principal visual material in a film or television production. In developing a storyboard, the principal frames of visual information that correspond to the written script are drawn and arranged in sequence with the script. Storyboards have long been used in the production of television commercials and spot announcements. Because these announcements are short, the visual parts of the program can be drawn in considerable detail. Storyboards are also used extensively in feature-film production; they allow the director to see what the film will look like before it is shot. In some cases, directors even make preliminary decisions about shot choices and the arrangement of visual sequences on the basis of the still frames in the storyboards. Storyboards are also used extensively in the development stages of animated features.

The treatment of the content of a program is reflected in the storyboard. Producers are expected to present such storyboards to clients or potential backers as the primary means of “pitching” the proposed production. Often, commercial clients expect to consider several treatments before commissioning a production. The storyboard need not include each shot that will be used in the final product, but it must include the major visual elements that establish the scope and tone of the production. The storyboard is arranged in proper sequence so that the progression of the narrative is clear and the integration of sound and picture can be considered in practical terms.

The storyboard is a working document subject to change as the production design evolves. It reflects the vision and discipline of the producer and often allows the production crew to anticipate problems and prepare solutions before shooting begins.

The development of a full script and storyboard is probably the best exercise the beginning video producer can undertake to plan out a production’s visual sequences. You can use a number of different storyboard formats. In the professional arena, storyboards such as the one shown in Figure 2.5 are common. The individual frames of the storyboard are arranged across the page, with the principal audio information written below. For producers who feel they don’t know how to draw well enough to construct a storyboard, computer programs with predrawn characters, locations, and properties are available at minimal cost (see Figure 2.6).

Full Script. Many single-camera productions are shot from a full script. In many ways, the use of a full script (and storyboard) creates the best of all possible production situations. Preparation of the full script and storyboard saves a great deal of time in the production and postproduction stages. Any program that is prepared for a client should be fully scripted. All educational/instructional programs and dramatic programs are fully scripted. Even many interview-based documentaries utilize very detailed shooting scripts. Although you may not know exactly what the interviewees will say, you can predict their general point of view and roughly the way they will answer your questions. The script can therefore describe in detail the program’s organization, the questions to be asked, and the predicted answers. This will serve as the initial shooting guide. Modifications in the script can be made after the field material has been shot to bring it into line with what was actually said in the interview.

Although there are a number of different kinds of full-script styles or formats in use, the two-column split-page format is one of the most widely used and one of the most useful to beginning video producers. In this script format, information about the program’s video is contained in the left column and information about the program’s audio is contained in the right column (see Figure 2.7).

The full script will contain sufficient detail to answer most production questions. Location and shot angle are specified. This, in turn, may suggest lens focal length, depth of field, and light requirements of the shot. The audio associated with the shot is also included because it is important to the duration of the shot and, if music is identified, to the rhythm of the shot, and to the speed of camera movement or movement of objects within the frame.

The full script is central to the calculation of the production budget. The production calendar is generated from the full script, as are equipment, location, audio, light, costume, and property requirements. These, in turn, lead to rental, transportation, food, insurance, and salary calculations (and profit, too, for that matter).

VIDEO SCRIPT

| Title: | “BRANCH PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT CASE STUDY” |

| Draft: | Final |

| Note: | Throughout the program, we hear natural background sounds appropriate to the scene. When we are focusing on people, at times we hear them speak under the narrator’s voice. We may understand a word or phrase here and there, but what they say is not important to the content of the program unless it is detailed in quotes. |

| VIDEO | AUDIO |

| Super Title: | |

| “Case Study: Part I: The Players |

|

| Fade Up On: | |

| 1. Exterior: Front of branch seen from street. Signage is clearly visible. We hear street sounds. | NARRATOR (Male Voice, VO): Welcome to the Longtree Branch of XXXXXXXXXXXX Bank. We’re located in a medium-sized California suburb. |

| Dissolve to: | |

| 2. Interior: WS (wide shot) of lobby. We see customers in line. | We serve a mix of customers with a variety of banking needs. Everyone from seniors to college students, merchants to manufacturers, middle-class families to professionals. |

| Cut to Pan of: | |

| 3. A TELLER crossing the lobby and approaching EDITH FARNSWORTH at her desk on the platform. There are pictures of her grandchildren behind the desk. The TELLER has a question for EDIE. | Edith Farnsworth, or Edie as she likes to be called, is our Branch Manager. Edie’s been with the bank for twenty years and is proud to have risen to the Branch Manager position. |

| 4. Another angle of EDIE. She is distracted from her conversation by something she notices in the branch (we do not see what it is). | She likes to be aware of everything that is going on in the branch and is always very busy. |

| 5. MS of DOROTHEA HALL. Pull back to reveal Edie conferring with her over a piece of business. They are standing somewhere behind the teller windows. EDIE nods, smiles at Dorothea, then exits frame. | Dorothea Hall is our Customer Service Representative. She and Edie have worked together since they first came to the bank as tellers. |

| Cut to: | |

| 6. DOROTHEA on phone. Hangs up and goes back to working on the daily report. | Dorothea handles customer concerns and problem phone calls referred by the tellers. |

| 7. CU of DOROTHEA’s face as she works. | She also compiles detailed daily reports for Edie. |

| 8. GEORGE BEALES at the merchant window. He greets an approaching customer as if they know each other well. | George Beales, our Purchase Merchant Teller, knows his customers well and enjoys working with them. He has been with the bank for six years and aspires to the job of Branch Manager. |

FIGURE 2.7 Full Script in Split-Script Format with Numbered Shots

The split-script format lends itself particularly well to the script breakdown. In the script breakdown, each shot is given a number (if this was not already done in writing the original version of the script), a shot list is compiled, and then—by considering the shot list and the availability of shooting locations and any actors/actresses (talent) who may be involved in the production—a daily shooting plan for the production is constructed. Figure 2.8 presents an example of a shot list, and Figure 2.9 presents the plan for one day’s shooting schedule on this production.

Preinterview

An extremely important part of the preproduction planning process is the preinterview. The preinterview is simply an interview scheduled before the production date with the program’s subject. Preinterviews are important to both the segment producer and the interviewee. From the producer’s perspective, a preinterview establishes contact with a subject and gives the producer initial permission to actually produce the piece. In terms of program design, the preinterview is an important point at which to gain familiarity with the subject in terms of the person and the content of the piece. The preinterview may well tell you what is important about the topic being investigated. This serves at least three functions: it provides initial information about the structure and content of the piece; it suggests possibilities for visual material to be incorporated into the piece; and it may suggest possibilities for interviews with other people or visits to other sites to gather additional information relevant to the program.

Often, the people who are the subjects of video field productions have not been on television before. For example, a magazine program that focuses on unusual people or unique local characters is likely to identify as subjects for segments people who have little experience on camera. The preinterview serves an important function for such subjects in that it allows them to establish rapport with the producer and/or other production personnel. This puts them at ease for the interview, particularly if a rough outline of the interview topics is discussed.

SHOT LIST:

Drug Diversion Program

Shot |

Camera Angle |

Description |

Location |

| 1 | LS | Probation officer giving instructions with people in background | Conference Room |

| 2 | MS | Probation officer | |

| 3 | CU | Officer giving instructions | |

| 4 | MS | Probation officer talking/holding agreement | |

| 4A | Zoom to CU | Zoom in to CU of agreement | |

| 5 | MS | Probation officer explains program to David | |

| 6 | MS | David paying fee | Front Office |

| 7 | MS | David turning in proof of completion | |

| 8 | MS | Probation officer talks about program | Probation Office |

| 9 | CU | Probation officer | |

| 10 | CU | Sign on courtroom doors | Courtroom |

| 11 | LS | Dolly into courtroom | |

| 12 | LS | Judge refers David to diversion program | |

| 13 | MS | Courtroom activity | |

| 14 | MS | Judge | |

| 15 | CU | Judge | |

| 16 | MS | David’s reaction (over the shoulder) | |

| 17 | CU | David |

There is no set way to approach the preinterview. Some producers are content to make the initial preinterview contacts with the subject over the telephone, whereas others prefer an in-person visit. In either situation, it is essential that the producer take accurate notes on the discussion. Some producers prefer to use an unobtrusive audiocassette recorder to tape the preinterview discussion.

When deciding whether or not to conduct a preinterview, several factors should be taken into account. Because the preinterview often entails a visit to the remote location, preinterviews are somewhat time consuming. This illustrates a major advantage to the telephone preinterview—it eliminates travel time and may be more efficient for the producer who is pressed for time. However, the producer who travels to the interview site can also conduct an on-site remote survey to gather information about the location.

SHOOTING SCHEDULE:

City and County of San Francisco

Adult Probation Department

Drug Diversion Program

| Date: | Friday, April 7 |

| Location: | Hall of Justice 880 Bryant St., Room 200 |

| Contacts: | Christina Marina 555-1718 Jimmy Lee 555-5717 |

| Time | Activity/Shot |

| 7:00–8:00 A.M. | Travel |

| 8:00 | Arrive and set up—Conference Room |

| 9:30 | Call: David and Probation Officer

Probation officer explains program procedure 1 LS with people in background 2 MS Probation officer giving instructions 3 CU Giving instructions 4 MS Probation officer talking/holding agreement 4A Zoom in to CU on agreement 5 MS Probation officer explains program to David |

| 11:30 | Set up—Probation Office |

| 12:00 | Call: David and Probation Officer

Probation officer explains the rules 6 MS Probation officer talks about program 7 CU Probation officer talks about program |

| 12:45 | Shot of paying cash (near office)

8 MS David paying fee 9 MS David turning in proof of completion |

| 1:00 | Lunch Break |

| 2:00 | Set up—Courtroom |

| 3:00 | Call: David and Judge Gross

Dolly Shot 10 LS Dolly into the courtroom |

| 3:30 | Shots in courtroom

11 CU Sign outside courtroom 12 LS Judge refers David to diversion program 13 MS Courtroom activity 14 MS Judge 15 CU Judge 16 MS David’s reaction (over the shoulder) 17 CU David |

| 4:30 | Strike equipment and leave |

Perhaps the greatest danger in the preinterview is that it may cause a loss of spontaneity in the actual interview. Few news producers who are conducting an investigative report would want their subjects to have the opportunity to rehearse their answers. Similarly, even in noninvestigative reports, subjects who appear to be reciting rehearsed answers to questions often lose credibility or destroy the credibility of the segment itself. The remote producer, then, must walk a careful line in conducting the preinterview. Important information about the subject should be gathered, and the subject should be put at ease, but this should not destroy the spontaneity of the interview, its personal nature, or the sense of discovery that makes an on-camera interview come alive.

Remote Surveys

Video producers working in the controlled environment of the studio know that they will always have adequate light for the production, adequate power for the equipment, and an acoustic environment that is insulated from unwanted, exterior noise. The video field producer has no such guarantees. Location production presents the production crew with an incredible array of variables that seldom concern the studio producer.

Every location is unique, so field producers adopt one of two strategies to deal with the peculiarities of different locations. They can bring along every piece of remote equipment imaginable, so that any production situation can be dealt with, or they can visit the remote location in advance of the production date to determine the location’s characteristics and the production strategies and equipment needed to shoot in that location. If they are fortunate enough to have a production van equipped with a wide array of power, audio, and lighting equipment, they are operating at a considerable advantage over the field producer who must order and budget each piece of equipment individually. Most field producers rely heavily on the remote survey—a technical and aesthetic assessment of a remote location—to provide important information about the location in which the shoot will take place.

Technical Factors. Any remote survey should gather data on at least three important technical factors: lighting, power, and sound. The available light in a location setting is extremely important. The remote survey should indicate what the nature of the available light is and whether there is enough of it to meet the camera’s baselight requirements. If the light is not adequate, then external lights or reflectors will be needed. If external lights are used, then the availability of power may be critical. Not only will it be needed for the camcorder but also it may be needed to run the lights if adequate batteries are not available.

The location should also be assessed for sound characteristics. You need to know what kinds of microphones and how many of each are necessary.

Legal and Safety Factors. Of primary importance with respect to the remote survey are certain legal and safety factors. The production crew should be able to operate safely in the remote location. The remote survey, therefore, should carefully identify any potential hazards on the location and determine whether the presence of the remote crew will create hazards. For example, consider a sequence that is to be shot on the floor of a warehouse where there is significant activity by forklifts moving pallets of merchandise within the production area. This should be duly noted in the remote survey. Will the crew be in the area in which the machines are operating? What will you do about the AC power lines? Will they interfere with the movement of the equipment?

Perhaps you plan to shoot a segment inside an elevator. How will you ensure that the elevator remains on the floor on which you are shooting? Will this present a problem to people in other parts of the building who might need the elevator to get from one part of the building to another?

Particularly in large buildings or industrial locations, it is always advisable to discuss the nature of the production with the maintenance or plant supervisor or the building supervisor. The supervisor will know about potential dangers that exist on the location and safety regulations that are in effect and may be able to help you solve technical problems with the location.

Aesthetic Factors. The remote survey should also note any relevant aesthetic factors apparent at the location. For example, the technical survey may indicate that sufficient light exists on location, but if it comes from a variety of sources with different color temperatures (e.g., a mix of daylight and fluorescent light), it may be difficult to set the camera white balance properly.

Similarly, notes on the visual character of the remote location may identify important architectural features that should be included (or excluded) from the production. Particular attention should also be paid to the sound environment. An interview scheduled in a house that is near the runway of a large, busy airport presents a challenging, if not impossible, situation for the audio person. A house next to a school playground may have appeared to be a suitable location for an interview if the remote survey was conducted while all the children were in class. However, if several hundred children are loudly playing in the playground during the remote shoot, it may be difficult to obtain a good audio recording of the interview.

Access to the Location. Your remote survey should also include information about access to the location. A primary concern is to obtain permission to shoot on the proposed location. If the property is private, permission from the owner should be obtained, preferably in writing. If the property is publicly owned, you will need to obtain permission from the appropriate agency. For example, in San Francisco, New York, and other large cities, permission must be obtained from the municipal government to shoot anywhere within the city. If you set up a camera and a tripod on a sidewalk, you must have the approval of the city agency that regulates these matters. If you are shooting a profit-making production, you may have to pay for the right to shoot and obtain an insurance policy that protects the city from damage suits in the event someone is injured during the production. If your project is nonprofit, the use fee and insurance requirements may be waived (see Appendix Two). Appendix Two presents an example of a shooting permit required in San Francisco.

Permission to shoot in local, state, or national parks usually involves submitting the appropriate application. Similarly, if you are shooting in a public facility, you will need to obtain the permission from the appropriate agency. To shoot in the local airport or railway station, or on a city-owned bus, permission must first be granted by the supervising agency.

Conducting the Remote Survey

It is never possible to anticipate all the problems that may arise on a location shoot. However, it is certainly better to conduct a remote survey and anticipate some of them than to skip the survey and go to the location totally unaware. Several guidelines can be used to help you conduct a good remote survey.

Survey When Conditions Are Similar to the Shoot. Try to survey the location at the same time of day and day of the week that you plan to do the actual shoot. If you plan to shoot on a weekend morning, survey the site on a weekend morning. This is primarily important in providing accurate information about the available light, but it is also important for other reasons. Traffic patterns and people patterns differ significantly from day to day (and certainly from weekday to weekend day) in many locations.

Bring a Viewer,Tape Measure, and Remote Survey Form. Bring a viewer or digital camera, a tape measure, and a remote survey form with you (see Figure 2.10). Director’s viewers, which enable you to see a location the way the camera will see it, are available from equipment supply houses. The viewer lets you look at the site and determine how it will look on camera. Also consider bringing along a digital camera. While the field of view produced by the camera may not be equivalent to the field of view produced by your video camera, it will nevertheless show you the location in a frame. It is also extremely useful in providing a photographic record of the location.

A tape measure is particularly useful. Measure the dimensions of any rooms that you expect to shoot in. Measure the distance between rows of objects that are important to the shoot. For example, you may want to dolly the camera between rows of bottles of aging wine in a winery, but you will be able to do this only if the distance between the rows of bottles is greater than the spread of the tripod dolly.

Make Parking Arrangements. Where will you park? If you are transporting a significant amount of equipment, you will need to be able to park your vehicle near the remote location. Is parking readily available? Will you need special permission to park near the shooting site?

FIGURE 2.10 Remote Survey Form

Consider Crowd Control. If you are shooting outside, how will you control the inevitable crowd of onlookers who will appear as soon as you set up the camera and lights? Even in the smallest amateur, nonprofit production, the appearance of a camera is sure to draw comments from passersby. Anticipate this and take steps to control the situation. For example, field producers who shoot in the skid row section of San Francisco have worked out an uneasy truce with local inhabitants. The production budgets usually contain a small fund used to pay off bystanders. A dollar or so will buy assurance that no one will jump in front of the camera when the tape is rolling.

Arrange for Food for Cast and Crew. You will need to provide food if your shoot lasts more than a few hours. The need for your cast and crew to eat should be seen as an essential part of the production and production planning rather than as a sign of weakness among crew members and cast. Is food readily available at the location, or will other arrangements need to be made?

Arrange for Bathroom Facilities. Consideration of the need for adequate bathroom facilities may seem to be far from the lofty ideals embodied in your program, but they are nonetheless essential.

Releases and Related Legal Issues

The video producer working for a television station or production house often has access to the legal department of the station or production center. However, many independent producers often work without the benefit of such readily available legal advice. Amateur, student, and independent producers may find that legal advice on production matters is available free or at low cost from their local media arts or community-access organization. In any event, there are a number of areas of legal concern that are of extreme importance to all video field producers.

Talent Releases. Perhaps the most important factor to be considered is the need for the field producer to obtain releases from those individuals who appear on videotape or from those individuals whose voices are used in a tape. To use someone’s image or voice in a production, you must obtain a talent release, which is a standard agreement signed by the subject giving permission for such use to the program producer or production agency (see Figure 2.11).

In documentary productions and other nonfiction programs or program segments (for example, magazine segments), talent releases are obtained from anyone who is interviewed as well as from anyone who can readily be identified in the picture, even if he or she does not speak. On remote locations, it is a good idea to warn people when videotaping begins so that they can get out of the camera’s field of view if they don’t want to be recorded.

For a fully scripted program using paid (or unpaid) actors and actresses, you should secure the appropriate talent releases well in advance of the production date. If the actors and actresses are paid for their services and sign contracts, the allowable uses of the performance will be specified in the contract. For unpaid talent, particularly in documentary programs or interview-based magazine segments, the talent release is usually obtained on the day of the taping. It is usually the responsibility of the producer to obtain the signed release.

Professional actors and actresses are familiar with contracts and releases. Nonprofessionals, who are frequently the people featured in student productions, are usually completely unfamiliar with releases. Therefore, it is extremely important that the producer, or someone else on the production staff, clearly explain what rights are conveyed to the production group when the release is signed.

There is little agreement as to whether it is better to obtain the release before an interview is recorded or after it. Obtaining the release prior to recording the interview is certainly preferable from the production team’s standpoint. Why waste time recording an interview only to be refused permission to use it in the end? On the other hand, many interviewees are extremely nervous about granting the interview, and being confronted with a decision about signing a release before the taping may cause them to refuse to participate. For such subjects, it may be better to wait until after the taping is finished and then obtain the signed release.

Many subjects are nervous about how their images and voices will be used. Most producers and editors are ethical people who want to use the best of what was obtained in an interview, not the worst. A simple assurance from the producer about the intention to use the good material will often put a subject at ease with respect to signing the release. If your production is noncommercial or educational in nature, this should also be stressed when asking the subject to sign the release.

Shooting in public places presents a unique situation with respect to obtaining releases from individuals in a crowd. Generally, the producer in such a situation is protected by the public nature of the area. However, it is always a good idea to make an announcement that the area is about to be videotaped or, if possible, to post signs with a similar announcement, so that anyone who doesn’t want to appear in the production will have the opportunity to get out of the camera’s field of view.

Video producers should also be aware of the special conditions that apply to the use of members of the American Federation of Television and Radio Actors (AFTRA) or the Screen Actors’ Guild (SAG) in their productions. AFTRA and SAG members are bound by the contracts of their respective unions, and if such union members are used in productions, specific rules apply to their working conditions and salaries. If you are working on a low-budget, nonprofit production, the unions will often grant waivers that allow you to use union members without paying the standard union wages. Waiver forms are available from the local office of the appropriate union.

Location Releases. As discussed earlier, location releases are sometimes necessary. Releases are often needed to shoot on city streets; in city, state, and national parks; and in public buildings such as government buildings, airports, and so on. The need for such location releases almost always extends to student producers, just as it applies to broadcast television producers. (See Figure 2.12.) In many situations, however, the student producer can obtain a waiver of the use fee usually associated with the release.

Location Safety. Field producers should also pay particular attention to the safety requirements in effect at any remote location. Depending on your location, a number of different state or local safety codes may apply. The Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) is a federal law that requires the states to set up safety regulations for employee protection. You should be familiar with local OSHA requirements and abide by them. If you are shooting in a factory, mine, or other industrial area, the plant supervisor can usually give you information about any OSHA requirements that apply.

Use of Copyrighted Music,Film, or Tape. Just as a release must be obtained from each person who appears in your production, so must permission be obtained if you plan to use any copyrighted material in your production. Violation of copyright with respect to music is very common but, nevertheless, illegal. Recorded music may not be used in a production unless permission is obtained from the copyright holder for its use. Similarly, any material that is broadcast or cablecast is almost always protected by copyright. It is illegal to tape something off the air and then incorporate it into your program. Permission must first be granted by the copyright holder. Troublesome and expensive legal hassles can be avoided if permission to use copyrighted material is granted before you use it in your program.

Releases are also critically important if you plan to enter your production in a video festival or media competition. Festivals and competitions routinely require entrants to certify that they have the rights to the material in their production. Typical of these requirements is the following statement from the Broadcast Education Association’s Festival of Media Arts release form, which the BEA requires all entrants to sign:

I, the undersigned, hereby warrant that I own and/or have obtained legal clearance of license to all contents of my Festival entry including but not limited to script; still and moving pictures; writings; talent; music and all other images and sounds.1

Stock Footage, Sound Effects, and Music. There are numerous sound and visual image (tape and film) libraries that supply material to producers for a fee. Stock tape and film footage are typically available, as are sound effects and music. For example, old newsreel footage is available for a fee from Movie-Tone News in Los Angeles. The National Geographic Society in Washington, D.C., has an extensive collection of stock footage of wildlife, which is also available for a fee. The National Archives in Washington, D.C., has millions of feet of old newsreels and government film, all of which is in the public domain. No royalties have to be paid to use this film, but the Archives charges a minimal fee to search for and transfer the material to videotape.

Access to sources of stock footage and music has increased markedly for producers in recent years. Most of the professional video trade publications carry advertisements for companies that provide stock footage and music. Many producers buy libraries of music on compact discs or subscribe to services that provide them with music on a regular basis.

Perhaps one of the most interesting and efficient ways to gain access to music and stock footage libraries is through the World Wide Web. A video producer who has a personal computer linked to the World Wide Web can search a wide variety of stock footage and music catalogs online. In many cases, it is possible to preview sound and video clips on your computer. One service, FOOTAGE.net, claims to provide access to nearly every stock footage library in the world through its online catalog service. (See Figure 2.13.)

If you are looking for a particular type of stock footage or sound, chances are good that you will be able to locate it and that rights to the material can be bought for a modest fee, depending on your intended use. The rights to copyrighted material cost more if you plan to use it in a widely distributed commercial production than if you plan to use it in a noncommercial program with a much smaller target audience.

Obtaining Original Music

One way to avoid the problems associated with obtaining permission to use copyrighted music in your production is to have someone compose original music for you. At first, it may seem more difficult to obtain original music than to write for permission to use already-written music. In reality, this is not always the case.

Many professional and semiprofessional musicians, as well as many music students, will jump at the chance to write an original musical score, particularly if it is going to be used in a program that will be shown to a large audience. In most cases, music composed specifically for a program will work better than already-written music. Make sure that you obtain a release to use the music in your program, just as you would obtain a release for the appearance of talent in your program.

Another way to obtain original music is to compose your own, using software that is readily available in several nonlinear editing systems or from other software sources. Programs like Apple’s Soundtrack and Garage- Band provide a library of sound effects and music loops that can be edited together to provide a unique soundtrack for your program. No additional releases need to be obtained to use this material in your project.

FIGURE 2.13 FOOTAGE.net Home Page

PRODUCTION

PLANNING

In many respects, while the actual process of shooting in the field is the focal point of the production, it can be a rather small part of the production process. This may seem like a paradox, given the amount of time this book spends describing production techniques, yet there is an element of truth to the statement. Preproduction planning and postproduction almost always take more time and energy than the time and energy spent on production itself. Weeks of preproduction planning may precede a one- or two-day shoot, and the material recorded during those two days may take another week or two to edit. Story or program conceptualization and development, script preparation, design of the storyboard, and coordination of all the preproduction elements require a considerable investment of time and creative energy. Alfred Hitchcock, the great film director, once commented that for him the most creative part of making a film was in visualizing the story and planning how he would shoot it. The actual process of filming the story was a technical exercise in which he merely tried to capture on film what he had already committed to paper.2

Admittedly, very few producers and directors possess Hitchcock’s skill in transferring to film or tape the ideas that have been planned out on paper. Indeed, if there is one given in visual production, it is that the finished product will differ from the planned product. Production in general, and the process of field production in particular, has a unique dynamic in which things that appear to work on paper often do not work in production, and things that do not look good on paper sometimes seem to come alive in the actual production. Nevertheless, the initial planning and visualization of the production process are indispensable to the completion of the project.

From the standpoint of production planning and organization, three critical factors emerge during field production itself:

1. Equipment needs for a shoot must be identified and satisfied.

2. Crew assignments must be clearly delineated, and responsibility must be delegated to the appropriate crew members.

3. The material that is shot must conform to the script or script outline, and the shoot must proceed efficiently.

Equipment Needs

The remote survey will tell a field producer precisely how much equipment is needed for a shoot. If a remote survey has not been conducted, then it is always wise to bring a little more equipment than you think you might need, particularly with respect to peripheral production equipment such as lights, microphones, cables, and so on.

In any case, a remote production equipment checklist serves as a guide to your available equipment and should be filled out when the remote survey has been completed. Figure 2.14 presents a typical checklist that should suffice for most producers involved in simple to intermediatelevel shoots.

Crew Assignments

The size of the crew and the responsibilities of the crew members vary with the type of production. An ENG crew, for example, may very well consist of two people: the camera operator and the on-camera talent. The camera operator, or shooter, has responsibility for operating the camcorder and thus principal responsibility for recording acceptable picture and sound. The on-camera talent, usually the segment or story producer, has responsibility for conveying the details of the story outline to the shooter, suggesting needed visuals, conducting required interviews, providing the on-camera stand-up introduction (or intro) and summary (or extro), and writing and delivering any additional voice-over narration. A more elaborate ENG crew might include an additional crew person who takes responsibility for sound recording.

In simple EFP shoots, characterized by those in which magazine segments are built out of on-location interview material, a three-person crew is often used. The producer has responsibility for story design and execution. The camera operator has responsibility for shooting the segments and for making sure that enough material is recorded to facilitate editing of the piece. The shooter, therefore, must make decisions about camera position, lens angle, zoom activity, and retakes of significant material. Although the field producer has the ultimate responsibility for planning the segment, the shooter has significant autonomy in shooting the visual material. A good shooter must be flexible and alert, and have a good eye for the visual potential of the scene and must also keep in mind the requirements of the editor and the editing process. This is necessary to obtain material that will make the piece visually interesting and coherent.

The production assistant (PA) in an EFP shoot serves a number of important functions. The PA takes responsibility for setting up any needed lighting instruments and microphones, functions as sound recordist (particularly if a fishpole-type microphone is used), and labels tapes as they are shot. The PA is often called on to set up and strike equipment and to make sure that an adequate supply of charged batteries is available. In addition, he or she is often responsible for driving the crew to and from the location. If the producer has primary responsibility for story design and the shooter primary responsibility for visualization, the PA has the responsibility for making sure that the shoot goes smoothly in a technical sense.

Many, if not most, EFP crews that shoot magazine-type material also use on-camera talent. Most often this is not the segment producer, and in this regard, magazine EFP differs significantly from ENG shooting. The questions the on-camera talent asks are developed through consultation with the producer, who has significant responsibility for directing the questions and producing the actual content of the piece.

These two types of production situations are fairly simple ones. In some production situations, the field production crew can be extremely large. For example, in the production of a dramatic script (whether it is artistic, theatrical, or instructional in orientation), the crew will most likely consist of a producer, director, camera operator, lighting director and assistants, audio director and assistants, talent, makeup crew, set designers and/or properties coordinators, and maybe even a stuntperson or two. In these full-scale productions, the director becomes the field production person with primary responsibility for coordinating all elements of the production. The director is responsible for visualizing the script and blocking (staging) the action and for communicating these decisions to the appropriate cast and crew members.

Regardless of whether the production has a designated director or the producer or camera operator acts as the director, the director’s role in the field is an important one. The director must delegate responsibility for performing production tasks to the various crew members, must have a clear idea of how the individual shots in the production will look, and must communicate that idea to the camera operator. The director must also analyze the shooting situation in order to direct the sequence in which shots or segments are recorded.

Efficient Field Shooting

With respect to the last point, the goal is to make certain that the most important things are shot first. The ENG crew covering a disaster in progress has to make quick decisions in the field with respect to what to shoot and in which order to shoot it. The magazine EFP producer has to decide on the order in which interviews and supplementary visual material will be recorded and how much time to allocate to shooting each element. The director of the dramatic script needs to break down the script into its component parts and decide how best to make use of the actors, actresses, and various locations.

Labeling Tapes in the Field

Just as thorough preproduction planning creates a record or plan of what is supposed to happen during production, tape labeling and logging create a record of what happens during production. Identifying individual tapes and their content is critical, not only to help the producer and editor keep track of what has been recorded but also because most nonlinear editing systems require every tape used in a production to be identified with a unique name or number. In addition, when you consider that even relatively short productions typically use several field tapes while complex productions may use 10, 20, or more, professional practice dictates that everything be labeled clearly.

Label Field Tapes as They Are Shot. Each tape should be labeled in the field as it is used. This is usually the duty of the PA. The most common method of labeling is simply to affix an adhesive label to the cassette box with the tape number and a brief description of the content, such as tape 1—glass-blowing B-roll. If an adequate number of tapes are available, you might want to record different interviews or shots from different locations on separate tapes. Each segment can then be clearly identified when it is time to edit the piece. This also eliminates the danger of accidentally recording over and erasing a segment. Also, if a field tape should be lost or destroyed, only one segment of material will be lost rather than a number of segments. As field tapes are recorded and labeled, the record safety device should be removed or engaged to prevent accidental erasure.

Slate the Tapes. It is common practice to slate the head of each tape for identification purposes. The slate simply records onto the tape information about the content of the upcoming material. This is extremely useful, particularly if the tape and its box should become separated.

If the content of the tape will be an interview, it is good practice simply to ask the person who is the subject of the interview to face the camera and state his or her name and occupation (or other relevant data). This will then serve to identify the person on the tape to the production personnel (and the editor, in particular). Another advantage of this type of identification is that it provides you with the correct pronunciation of the subject’s name. Because the narration that will be added to a piece may well contain a reference to the name of the subject, correct pronunciation is essential.

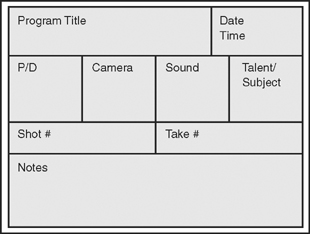

Another method of slating involves the use of a formal production slate that is held in front of the camera at the beginning of the tape and at the beginning of each shot. An example of a production slate is shown in Figure 2.15. The slate should contain the essential information about the production. It is common to include the title of the production and the names of the director, producer, and camera operator; the date; the shot and take number; and any other relevant notes. This kind of formal slate is typically used only when the production being videotaped is fully scripted. Because individual shots within the script need to be staged and recorded, the slate serves as a simple and consistent way to identify the shots on each tape. If multiple takes of a particular shot are recorded, the good take can be distinguished from the bad takes by reference to the take number.

Once the field footage has been recorded, it is time to begin planning the postproduction or editing phase of the project. This phase is described in detail in Chapter 10.

COPYRIGHT AND

DISTRIBUTION

Copyright

Copyright has been discussed earlier with respect to obtaining permission to use material that has been copyrighted by someone else. However, as a producer of a complete program, you may decide that you want to protect your rights to the program you have produced. This is particularly important if you believe that your program has commercial potential or if you want to control its distribution and display.

A video program automatically gains copyright protection as soon as it is created and “fixed” in a copy; that is, when it exists in recorded form. However, to protect against copyright infringement of your work, the U.S. Copyright Office recommends that the copyrighted work display a copyright notice including the word Copyright or its symbol (©) or abbreviation (Copr.) as well as the name of the author of the work and the date of its first publication; for example, © R. Compesi, 2007.

The U.S. Copyright Office registers claims to copyright and issues certificates of registration. To obtain a copy of the form used for programs produced on videotape—Form PA (for works of the performing arts; see Appendix Three)—contact the Register of Copyrights, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20559. You can also obtain a copy of the form online at http://lcweb.loc.gov/copyright. Then send the completed form, the filing fee, and a copy of your videotape to the Register of Copyrights at the address provided above.

Generally, if you produced your program independently, you will be considered the author and owner of the program. If you produced it for your employer, then the program is a work made for hire and your employer will own the copyright. If the program is a specially commissioned work, it will be owned by your client if you sign a “work made for hire” agreement. If you are a student at a college or university, you should check your institution’s policy with regard to copyright. Many schools stipulate that they be named the copyright owner for any programs produced using their facilities.

The length of time that the copyright remains in effect depends on the status of the owner. If you are the program’s author, the copyright term is for the length of your life and 70 years after your death. If your program is a work made for hire, the copyright will protect it for 95 years after its first publication.

Distribution

No discussion of production planning is complete without at least some mention of the area of distribution. For the home video producer or the student working on a class project, the issue of distribution is relatively simple: you assemble a captive audience (friends, family, classmates, or instructor), put the videotape or DVD into a playback machine, and then observe their response. Similarly, the employee of a broadcast or cable station is usually not overly concerned about distribution—the program or segment is completed and then aired as part of an individual program or series.

For the independent producer, however, the area of distribution is critical. We all make video programs to be seen, and in many cases we hope that they will be seen by rather large audiences. The problem of distribution, then, is one of maximizing the exposure of the program to its target audience.

In recent years, the opportunities for distribution of visual materials have opened up somewhat. Whereas only a few years ago the options were limited, the proliferation of VCRs and DVD players in education and industry, the expansion of the cable television industry, and access to public broadcasting and public access cable television have given independent producers a number of realistic alternatives for distribution. In addition, the large number of video festivals and competitions throughout the country also provide a significant number of outlets for visual materials.

The type of distribution you desire depends quite clearly on the program’s content and target audience. Producers of educational materials might find a receptive market among public broadcasters or any one of the educational program distribution services. Documentary producers have traditionally had a rough time earning back the cost of their investment but nonetheless have a number of distribution options. Video festivals, public broadcasting, subscription cable systems, and individual sales to libraries and other organizations all provide potential outlets and sources of revenue. A program on cancer, for example, might be attractive not only to a number of broadcast or cable outlets but also to local (or national) cancer societies or other health agencies. Individual hospitals might be interested in the program if it could be used for counseling or providing basic information to patients.

One of the fastest-developing areas for distribution of video content is via the Internet. Programs or program segments not meant for cable or broadcast distribution may be posted on a web site for viewing via the Internet.

Clearly, you need to accurately assess the market potential of your program in its initial stages of development. If you’re contemplating a widespread sales campaign, then you need to develop promotional material and a list of potential buyers. An independent producer can rent out or sell tapes and DVDs and can distribute them independently (through selfdistribution) or through an established distribution service.

NOTES

1. Broadcast Education Association. BEA Festival of Media Arts Release Form. Available online at http://www.beafestival.org/release.html.

2. Crawley, Budge; Markle, Fletcher; and Pratley, Gerald, “I Wish I Didn’t Have to Shoot the Picture: An Interview with Alfred Hitchcock,” in LaValley, Albert H. (ed.), Focus on Hitchcock, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1972, pp. 22–27.