p.42

A critical analysis of the role of humor in activist–business engagement

Katharina Wolf

Introduction

This chapter provides a first-hand, in-depth insight into humor-based activist–organization interaction based on a single case study. Although extensively examined in social science literature,1 humor is arguably not a characteristic that is frequently associated with activism in mainstream Western culture and psyche. Historically, business and communication scholars have examined the activist–business relationship primarily through an organizational lens. In providing an alternative—activist-focused—perspective, this chapter addresses an existing gap in the literature. It challenges current understanding and assumptions, and hence the way businesses seek out to engage with activists and ‘manage’ opposition. Based on in-depth observations I argue that comedy, wit and hilarity have traditionally performed a crucial role in activist communication and continue to do so today. However, the communication styles and tools utilized by activists tend to differ from those used by professional organizations, which employ humor for very specific and distinct purposes. The unfamiliarity and adverse connotations associated with street theater, clowning and playful communication in a business context may lead to activists being injudiciously misunderstood or dismissed as unprofessional and amateurish. However, much of this conclusion may be based on misconceptions and the assumption that humorous protests are targeted at and performed for the benefit of organizational representatives, which is being contested in this chapter.

Street theater inspired actions and small protest are not unique to Australia and are certainly not uncommon, ranging from localized protests to international, humor-based campaigns by established networks and non-government organizations (NGOs). Nevertheless, these types of ‘actions’—in particular at a community level—tend to take the business community by surprise, as they represent a dramatic contrast to the way corporations communicate, negotiate and function on a day-to-day basis. Within a business context, humor is largely used as a means to an end, for example as ice breaker at the start of meetings or discussions, or as part of team building exercises and staff development. Although the benefits of comedy and in particular clowning are recognized within professional contexts, such as health2 and even corporate staff training (see e.g. www.nosetonose.com and www.circusunique.com.au), the concept of humor remains undertheorized and frequently misunderstood within the context of professional and/or business communication.

By providing an alternative perspective on activist–organization engagement and its drivers, this chapter challenges the use of humor as leveler and bridging tool. Instead, the author argues that within this context humor arises naturally out of irreconcilable differences and the lack of a common ground. I thereby question the business community’s assumptions and ‘best practice’ approaches related to activists’ interest in being consulted and co-opted into projects and developments, encouraging a review of approaches and the allocation of resources.

p.43

Activist–business engagement

This chapter investigates professional communication and activist–business engagement from a public relations perspective. As a multidisciplinary field, the public relations perspective enables scholars to draw on relevant literature and scholarly insight from a range of related subject areas, including management, organizational behavior, business studies, linguistics, psychology and marketing. Furthermore, a key focus of public relations is organizational engagement with a wide range of key stakeholders, in this case between business representatives and community activists. Moreover, activist–business engagement and activist communication represent one of the largest bodies of knowledge in the public relations literature, therefore providing useful and relevant insights for the purpose of this chapter.

Best practice communication theory has traditionally been built on the concept of (symmetrical) two-way communication3 and the assumption that a compromise is the desirable best practice outcome for any form of stakeholder engagement.4 Within this context it is important to note that the public relations activism research agenda has historically been largely limited to the corporate perspective, motivated by a focus on issues management and damage limitation.5 Activists have been predominantly framed as entities that disrupt meaningful engagement. Hence, they need to be managed, quieted, and moved on, so that organizations, corporations and governments can engage with those communities that may be less confrontational and more inclined to seek out a compromise. More recently, critical scholars have strongly questioned the notion of negotiating a ‘middle ground’ or ‘win–win zone’ as a desirable goal of ‘excellent’ public relations, as a ‘compromise’ may not appeal to those activist groups who are entirely opposed to a business proposition or policy decision.6 The author argues that there are some activists, particularly those interested in broader (global) issues, who are not interested in engagement at a meso level. There is no such thing as a middle ground for networks like the no coal alliance or—as in this case study—the anti-uranium movement, i.e. groups that are entirely opposed to the future of mining of certain raw materials. Instead, the aim of their communication efforts is to raise awareness and challenge the status quo. Hence, what may be perceived as a humorous action performed for the benefit of organizational representatives is a crucial means for activists to strengthen their internal bonds, re-energize themselves and raise awareness of an issue amongst the broader community. Furthermore, the concept of balanced, two-way communication as championed in the extant literature essentially ignores the unequal distribution of power between activists and organizations,7 which is usually in favor of the commercial entity.

The role of humor in business communication

Although multidisciplinary by nature, ‘humorology’ has evolved into a field of research in its own right, with dedicated scholarly journals, such as Humor: The International Journal of Humor Research, The European Journal of Humor Research and The Israeli Journal of Humor Research. Scholars refer to humor as a “powerful communication tool.”8 Its use—and positive effects—have been particularly highlighted within the context of business negotiations9 and any other form of communication where persuasive techniques may be required,10 such as meetings with key external stakeholders, or internal (e.g. pay) negotiations. Within this context humor acts as a power leveler11 and can be used to “diffuse tension, mitigate a possible offense, introduce a difficult issue, and thus to pursue one’s own goals.”12 Its use can aid in lowering defenses and hence invite others to open up to new perspectives.13 Research has furthermore suggested that humor can compensate (to some extent) for weak arguments.14 However, scholars warn that some types of humor are more effective than others. For example, studies identified persuasive benefits specific to the use of irony,15 which may explain why some studies have identified the use of ironic exaggerations as the most common type of humor used in (business) meetings.16

p.44

Additionally, humor contributes to social cohesion in the workplace, by increasing feelings of solidarity17 or collegiality between co-workers,18 i.e. humor aids in breaking down existing hierarchies and potential barriers by creating communities of shared understanding and a sense of belonging. However, there is consensus amongst scholars that styles and dominant types of humor depend on the context, initiators and the overall aim of humor use. Hence, existing studies suggest that different communities of practice have dissimilar ways of doing humor.19 This observation is arguably particularly relevant within the context of this study, where two distinct ways of communication and styles of humor collide as community activists confront business representatives in the reception area of their head offices, as will be described later in this chapter.

Beyond its much celebrated benefits, multiple studies have highlighted the drawbacks and challenges of humor use in (business) communication. For example, communication scholars have traditionally warned against the pitfalls of using humor in cross-cultural communication, due to translation difficulties and differing preferences in terms of humor styles,20 which may essentially result in a reduction of communication effectiveness. Furthermore, multiple studies refer to the double-edged nature of humor use. As much as it is recognized for its ability to unite communicators and facilitate collaboration, humor simultaneously has the ability to alienate and divide, through the (re)enforcement of norms and delineation of social boundaries.21 For example, in meetings, humor does not tend to challenge existing power relationships, which are usually predetermined and relatively static.22 The acceptable and chosen style of humor therefore tends to be determined by an already powerful group,23 which may result in the emergence of sub-groups and collusion against each other.24 Hence, humor can have a dual purpose; both as a unifier and divider: as much as it can be used positively to promote inclusion, it may equally have negative effects, through the facilitation of collusion, exclusion and the emphasizing of differences between participants.

The use of humor in activism

Humor has a long history as a tool to “confront privilege, weaken the power of oppressors and empower resistance.”25 A classic example of this is the royal court jester, who could express critical thoughts about policies without fearing punishment.26 Lievrouw27 similarly argues that activists’ political and artistic heritage is in Dada and situationism, which leads to the use of irony and humor as a means to confront power, challenge the status quo, and emphasize alternative points of view via, for example, culture jamming, flash mobs, or provocative media artifacts. Hence, humor is frequently employed by social movements and community activists as a communication strategy in its own right. Scholars have argued that humor naturally complements other forms of activism, in particular political activism and protest.28

p.45

Within this context it is important to note that scholarly literature, industry publications and the media commonly refer to activism as a monolithic concept and practice, encapsulating well-established and funded international non-government organizations and mass demonstrations, as well as community groups, individual ‘active’ citizens and signatories of petitions. This conceptualization of activists as a homogenous entity implies that international NGOs, like Greenpeace and Amnesty International, can not only be studied in the same way, but are by implication comparable to other forms of activism, such as localized community groups or context-driven, heterogeneous social movements, such as the Arab Spring or Occupy Wall Street. It is not disputed that some international NGOs, such as the World Wildlife Fund, have deliberately positioned themselves to work with corporate entities to negotiate a compromise and hence sustainable solutions to business challenges. Within this particular context, the community building features of humor, as noted above, provide obvious benefits, by lowering defenses and encouraging both business representatives and activists to open their mind to the other party’s suggestions and perspectives. However, the focus for this chapter is the use of humor in community or grassroots activism and what Smith and Ferguson29 define as issue activists, i.e. individuals focused on border-spanning causes (e.g. global warming, landmines, or pollution). The author argues that within this context there is often no middle ground to negotiate, as activists are entirely opposed to a particular business proposition. Hence, I contend that contrary to best practice communication theory and industry assumptions, the anti-nuclear activists observed as part of this study do not use humor to engage and collaborate with business representatives. Instead, they use humor for their own purposes to illustrate differences in aims and priorities between commercial entities and the broader community, and to challenge the status quo.

Method

Activists’ engagement in business contexts has traditionally been examined through a corporate lens, characterized by a heavy reliance on conceptual papers and minimal insights into the activist perspective. This study aims to address current gaps in the literature by gaining real-time, first-hand insights into activist communication. In this chapter the author sets out to challenge the common underlying assumptions of activists seeking some form of a compromise—or indeed any form of engagement—with business representatives within the context of humorous actions, by investigating activist–business engagement through the eyes of community activists.

This case study is part of a larger, longitudinal study into activist communication, which follows an ethnographic approach to explore the activities, interests and motivations of activists affiliated with the West Australian anti-nuclear movement (WA ANM). A range of methods have been employed, including participant observation for multiple, extensive periods at the movement’s planning meetings and public actions; interviews with activists; and qualitative document analysis of activist texts (such as flyers and brochures), as well as media coverage such as newspaper articles, online reports, and broadcast programs, including audience comments and subsequent discussions. For the purpose of this particular case study, close attention was paid to activists’ artifacts and the wider support community’s online communication in response to first-hand insights into this particular humorous action, which targeted a local mining operation, as well as the (re)distribution of the resulting video and photos via social media. Despite the existence of a video channel and Twitter account, interaction and ‘sense making’ of public actions has traditionally been largely limited to Facebook, i.e. the group’s profile, related accounts and comments from individuals in response to posts, photos, videos and others’ statements. Face-to-face interactions and reflections at planning meetings, as well as at consequent actions further contributed to this case by providing insight into activists’ interpretations of individual actions and engagement with business representatives that would not have been captured as part of a structured interview process.

p.46

A grounded theory approach was chosen for this study, as this is considered particularly suitable for the exploration of social organizations from the participants’ point of view30—in this case, through the eyes of West Australian (WA) anti-nuclear activists, as opposed to the organization in the premises of which the action took place. To overcome the scarcity of existing knowledge and insights into humorous activist–organization engagement from the activist perspective, a single case study approach was selected, enabling the author “to collect ‘rich,’ detailed information across a wide range of dimensions.”31 This includes records of media reports and online engagement; images, photos and screenshots; personal notes on observations at public actions and group meetings; audio files of interviews and subsequent transcripts; as well as a reflective diary that was kept throughout the longitudinal study. Data have been stored and coded with the aid of the software package NVivo. The central storage location enabled the continuous analysis and coding of data throughout this study. It allowed the data to gain meaning in the form of key themes and helped to identify further areas for data collection.

The West Australian Anti-Nuclear Movement (WA ANM)

The WA ANM is a collective of not for profit organizations, community groups and individuals that are opposed to the use of nuclear technologies during any stage of the nuclear fuel cycle.32 This covers the exploration, mining and export of uranium ore, as well as the use of uranium for the purpose of energy generation and warfare. The global anti-nuclear movement was arguably most active and visible during the 1960s and 1970s. Interest in and support for the anti-nuclear movement in Australia may have diminished since hundreds of thousands of supporters took to the streets in the 1980s to participate in mass rallies.33 However, the anti-nuclear movement remains relevant due to the unique circumstances Australia finds itself in. On one hand, Australia is recognized as one of the world’s major uranium exporters34 and home to the world’s largest uranium reserves.35 However, on the other hand, despite much debate and speculation over the past decades, Australia does not have any nuclear power stations, with the exception of a research facility, which is largely used for medical purposes. A number of factors have ensured the anti-nuclear movement’s continued activity and relevance: the framing of nuclear energy as an affordable, safe and—arguably most importantly—low carbon response to the threat of global warming by the nuclear lobby;36 major international incidents such as the nuclear meltdown and release of radioactive material at the Fukushima Daiichi Plant in Japan following an earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011; increased calls for nuclear waste to be stored in the Australian outback; and reversals of state-based uranium mining bans, such as in Western Australia in 2008.37 Hence, the WA ANM has been a prominent voice in Australian politics and social commentary for over four decades, although activists’ focus may have shifted over the years from opposition to nuclear weapons testing to the prevention of the mining of uranium.

p.47

The movement has traditionally been characterized by its dedication to non-violent direct action (NVDA) and civil disobedience, which highlight the appropriateness of humor, street theater and satire as crucial campaign tools and recognizable characteristics of the WA ANM. However, the author argues that the concept of humor is largely misunderstood and underutilized within an organizational—and in particular a corporate—context, which can lead to activists’ capabilities being underestimated or even dismissed as ineffective, childish and amateurish. Organizations fail to recognize the multiple, crucial roles that comedy, wit and hilarity perform in sustaining movements and community groups,38 by wrongly assuming they themselves are a key target audience of—or even a vital participant in—humorous actions. In this chapter I argue that humor arises naturally out of the contrasting communication styles preferred by activists and the organizations whose practices they challenge. Business representatives and their offices provide merely the props and stage setting, whilst the true target audiences are fellow activists and the broader community.

This chapter challenges the role of humor as power leveler and community builder in activist-organizational engagement, arguing that its actual intention is the complete opposite. This theory will be further investigated and substantiated on the basis of a case study outlining observations of activist–organization engagement throughout the next part of this chapter.

Findings

Case study: Toxic Office Clean Up

Flanked by his office manager and front desk staff, the chief executive officer of a middle-sized mining company watches with astonishment as, without prior warning, five flamboyant characters empty multiple bags of bright yellow sand onto the polished floor tiles in front of him. Donning colorful wigs and scarves, feather dusters, buckets, mops and brooms, the representatives of what appears to be a ’70s-style cleaning crew waste no time in spreading the fine sand throughout the otherwise pristine and arguably sterile reception area. The contrast between the clean cut, professional business environment and the five representatives of a local grassroots group gives the entire event a somewhat surreal effect. One activist attentively films every detail, as his peers embrace their characters and the chaotic atmosphere, without taking much notice of the small group of business representatives that has gathered—and continues to grow—behind the glass doors leading to the main offices. There is head scratching and bewilderment amongst the workforce. Some point their phones in the direction of the activists to record the strange events with the intention of sharing this experience with colleagues and peers. Others are on the phone to security services. However, all appear to be somewhat mystified about the scene in front of them, struggling to make any sense of it. The activists make no demands, nor any efforts to communicate or to raise any concerns. Less than four minutes after the group has confidently entered the reception area, they are escorted off the premises by two suited security guards. They do not protest, simply shout over their shoulders “clean up your mess,” and spill giggling back onto the pavement, as their every move is recorded on a small handheld camera.

The events described above took place in late 2012 in the Central Business District (CBD) in Perth, Australia, and are just one example of a string of protest performances by local, national and international representatives of the anti-nuclear movement, opposing the exploration of uranium in (Western) Australia (and beyond). Through a professional communication lens, these activities appear to be pointless and fail to make any sense, especially as no attempt is being made to communicate or engage with representatives from the mining company. The spreading of the sand is later framed as vandalism in the local business news and activists are publicly condemned for their “irresponsible behavior” and “time wasted.”39

p.48

However, these (public) interpretations of this short public action are entirely based on an organizational perspective. Through the eyes of participating activists and their wider support community the above scenario signified time and resources well invested, as illustrated in the resulting video and related online discussions, supporter comments on Facebook and references to the Toxic Office Clean Up in consequent email exchanges, planning meeting and their official records.

Cultural differences in humor use and appreciation

As discussed earlier, communication literature commonly cautions against the pitfalls associated with using humor in cross-cultural communication. This case study arguably emphasizes this point, as organizational representatives struggle to make sense of activists’ actions, failing to understand what the activist community perceives as so hilarious about their Toxic Office Clean Up initiative. From an organizational perspective there is nothing humorous about the event. Instead, the incident appears childish and pointless, representing an unwelcome disruption to the workday with no clear objectives, demands or attempts to engage.

This brief scenario emphasizes that humor is ultimately culture-bound, i.e. dependent on what is considered to be amusing, or indeed appropriate behavior amongst a group of actors with shared values.40 Although jokes may take place in virtually all organizations and groups, the appreciation of a joke usually requires a shared cultural background, assumptions and beliefs. Within this context culture should not be understood in the narrow sense of ethnic or national identity, but refers to a discourse community that individuals belong to and to which underlying stylistic conventions they prescribe. Conversely, humor can provide insights into the distinctive culture which develops in different workplaces or communities of practice.41 In this case, both groups may be concerned with the mining of uranium and have similar subject knowledge; however, their interpretation of the world around them, associated values and priorities differ starkly. This context and shared understanding ultimately influence communication and humor styles.

For example, within the grassroots activism context there is a strong emphasis on clowning, carnivalesque actions and street theater,42 which are forms of expression that are uncommon in day-to-day business contexts. Slapstick humor, dress ups, drama and colorful costumes are all integral parts of the WA ANM resources kit. Their contrast to the sterile business environment, decision makers in suits and perceived humorless attitude increase their attractiveness for activists and leads to humor arising naturally. However, I argue that in dismissing activists as ineffective, business representatives commonly misunderstand—or even overestimate—their own role in humorous activist actions. In interviews and informal discussions WA ANM activists emphasized a lack of interest in engagement with corporate representatives, largely driven by a fear of being co-opted into a project or business decision. (Corporate) Consultation processes were being interpreted as meaningless and tokenistic. Hence, humorous protest is not being enacted for the benefit of the business community. Business representatives’ confusion and their apparent inability to see the funny side of the action, ultimately lead to hilarity among performing activists and the subsequent audiences’ first-hand accounts of the ‘action’ in word, print, images and video. Although humor has the ability to become a unifier, breaking down existing boundaries and hierarchies, in this case humor is used as a divider, creating an ‘us vs. them’ scenario, which further strengthens the identity of and solidarity amongst activists and their broader support community. This is illustrated in on- and offline discussions following the Toxic Office Clean Up, where supporters shared in the hilarity surrounding corporate representatives’ puzzlement.

p.49

The role of humor in activist–business engagement

Business scholars have highlighted the effectiveness of humor use in persuasive communication,43 which may lead to the assumption that activists seek to engage with organizations—via humor and other means—in order to have their voice heard and to potentially contribute to some form of negotiation or compromise. However, a critical analysis of communication (email, social media, discussions at meetings, informal engagement and interviews) surrounding the Toxic Office Clean Up action indicates that community activists such as the WA ANM do not set out to persuade business representatives of their point of view. From an anti-nuclear perspective there is no room for negotiation or a compromise with mining operations. Company employees are merely discussed as bystanders and part of the stage setting. However, at no stage was any direct engagement or interaction with representatives of the targeted organization planned or even considered.

As discussed earlier, irony has been identified as the most common and effective form of humor in a business context.44 However, within the context of the Clean Up action, irony does not arise from a common denominator, shared understanding, or similar values, but from the fact that business representatives do not understand WA ANM activists’ actions. Hence, their confusion and bewilderment as captured in the video actively contribute to activists’ amusement; both during the actual action, but even more so when recordings and photographs are shared and discussed with the wider support community in person and via social media. The stark contrast between the office environment and the clean-up crew, corporate dress and colorful costumes, the uneasiness of corporate representatives and confident determination of the ‘clean-up crew’ all add to the embedded irony and overall effectiveness of the stunt from the activist perspective.

Underlying power relationships do not tend to be dynamic, but dependent on available resources—both symbolic and financial. Humor can be utilized to overcome hierarchies and power differences; however, scholars emphasize that essentially the more powerful entity determines what is funny, what type of humor is acceptable, who can start a joke and—most importantly—if the style of humor is inclusive or exclusive of the less powerful group.45 In choosing a style of humor that is unfamiliar to the corporate context, WA ANM activists effectively undermine existing power relationships and distribution, challenging norms and preconceptions. Essentially, their aim is not to convince business representatives of their point of view. At no point of this study have any objectives been set that relate to consultation, direct engagement with corporate representatives or the direct influence of business goals by the WA ANM. Humorous actions may contribute to individual activists’ enjoyment of their involvement, but they ultimately exist to engage the broader community, which is illustrated by the fact that the action itself is recorded in video and stills and widely shared via social media and personal networks.

Different types of humor construct different types of relationships. According to Holmes and Marra,46 humor is a means to maintain “sustained mutual relationships,” which by nature can be harmonious, but may also be conflictual. Rogerson-Revell47 similarly refers to humor’s ability to reinforce solidarity, or to contribute to what she labeled distancing. Hence, whilst humorous actions like the Toxic Office Clean Up may contribute to harmony and feelings of solidarity amongst activists and their wider support community, they simultaneously serve as an acceptable vehicle to express subversive attitudes and negative feelings towards mining representatives. Therefore, preferred humor styles may act as boundary markers, which reinforce differences between activists and commercial entities.

p.50

Humor and laughter have traditionally served as powerful tools in social protest, contributing to social cohesion, a strong sense of unity and belonging.48 However, within this context ‘unity’ does not refer to engagement and collaboration with the targeted mining company and its representatives, but to the strong internal community building features provided by comedy, hilarity and absurdity, which allow activists to strengthen the bond among participants, as well as to reach out to their supporters, networks and likeminded groups. On- and offline discussions prior to and after the Clean Up action indicate that there was no desire to utilize humor to engage with organizational representatives. Humor is invoked to make both alliances and distinctions.49 It is used to highlight differences and strengthen connections within individual groups, especially as part of cross-cultural communication.50

Within the context of the Toxic Office Clean Up action, humor is utilized to distinguish activists from the mining business. This ‘us vs. them’ ideology contributes to the level of hilarity and increases the stickiness and appeal of resulting artifacts, such as photos, videos and first-hand accounts amongst activists and their wider support network. Recent studies have found that sarcasm and silliness are the most common and effective forms of humor used on social media networks, such as Facebook.51 Furthermore, emotions evoked have been determined to be more important than the actual content in political satirical videos.52 Hence, costumes, the clumsiness of the characters and the disruptive nature of the Toxic Office Clean Up action itself, as captured in humorous videos53 and photos and subsequently shared online with the wider community, are therefore arguably more valuable and effective than any factual discussion about uranium mines or angry protests could ever be. Humorous actions empower audiences by making them laugh at the inability of corporate representatives to make sense of the clean-up action. Despite the limited subject-specific, educational content, records of the Toxic Office Clean Up action draw attention to the cause and encourage viewers to challenge the status quo, based on which corporate entities are assumed to hold the balance of power.

Discussion

Business and communication scholars have traditionally emphasized the notion of a compromise, or the negotiation of a win–win zone, as best practice in organization–activist engagement.54 Hence, through a corporate lens, initiatives like the Toxic Office Clean Up appear to be unprofessional and immature, by failing to clearly outline objectives, demands and alternative viewpoints. This interpretation is clearly captured via the visual recording of corporate representatives’ facial expressions and body language, as well as indirectly in the consequent criticism of the WA ANM’s action in the business press. However, these interpretations are based on the assumption that the organization is the actual target of the brief performance, implying that activists actively seek to engage with corporate representatives in an effort to influence decision making (in this case their determination to pursue uranium exploration rights).

p.51

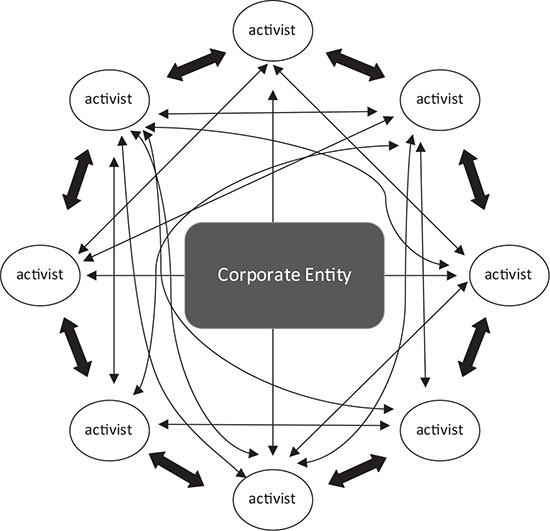

Figure 2.2.1 A visual representation of humor arising from activist–organization engagement

In lieu of the goal of persuasion, community activists such as the WA ANM use humor as a tool to confront, divide and ultimately to highlight irreconcilable differences between the business and activist perspectives. As illustrated in Figure 2.2.1, activists in this case study do not seek to engage with business representatives. Instead, humorous actions emphasize irreconcilable differences between participants and the business community and are targeted at likeminded people, i.e. fellow activists and the broader community of supporters. As traditionally powerless—or power lacking—entities in the organization–activist-relationship, community activists utilize the capabilities of humor to confront privilege and challenge preconceived assumptions. In doing so, they frequently employ different styles of humor to those employed in a business context, which may lead to organizational representatives dismissing activists as ineffective. However, this contrast in communication styles—hence styles of humor—and the resulting bewilderment by business representatives are key to the success of humorous activist actions, as they challenge preconceived power relationships and communication preferences. Rather than setting out to build solidarity and understanding, or to initiate further engagement, activists use organizational representatives as props and a crucial element of their stage set; both in real time and as part of resulting artifacts, such as videos, photos and first-hand accounts.

Conclusions

Business leaders feel somewhat helpless when confronted by a gaggle of clowns, a singing group of pensioners or other colorful characters, all of which are crucial elements of activist groups such as the WA ANM and similar collectives. Faced with a communication style which is entirely removed from their day-to-day expectations and assumptions, the business community is inclined to dismiss grassroots activists as unprofessional, ineffective communicators and time wasters, as detailed in related news articles and resulting commentary. ‘Hippies,’ ‘tree huggers’ and ‘clowns’ are some of the derogatory terms frequently used to describe participants in these types of actions in the (local) media, alongside the assumption that activists are unemployed and hence have nothing better to do with their time. This chapter challenges these preconceived assumptions by providing first-hand insights from the activist perspective, disputing the notion that businesses are the principal target of humorous actions. It furthermore challenges preconceived assumptions by the business community relating to ‘best practice’ approaches and activists’ interest in being consulted and co-opted into projects and developments. If resources are to be used in a cost effective and productive manner, any relationship—including activist–organization engagement—needs to be examined from both sides and communication approaches tailored accordingly.

p.52

Based on observations, interviews and the analysis of related artifacts, I argue that in this context humor is an asymmetrical communication strategy intended to create conflict with, and encourage resistance to, dominant social discourses. Humorous actions by community activists, such as the Toxic Office Clean Up, challenge best practice communication theory and the notion that collaboration should be a core aim of activist–organization engagement. Instead, activists advocate conflict, resistance and irreconcilable differences as important contributors to democratic processes, by ensuring exposure of alternative perspectives and the drawing of attention to issues close to their heart (in this case uranium mining).

Drawing on more than two years of participant observation at planning meetings, actions, Annual General Meetings and industry conferences, the author argues that the business community has failed to understand the true drivers and motivators behind humorous activist activities. I challenge the notion that activists exist in opposition to organizations and instead argue that grassroots activists frequently do not seek to engage with business representatives and may instead even actively avoid being consulted or entering any form of relationship based on the notion of a compromise. Grassroots activists such as the WA ANM identify themselves as facilitators of democratic decision making. Their perceived role is not to convince business leaders of their point of view or to enter negotiations. Instead, they draw on humorous actions to raise awareness of issues that are close to their hearts in an effort to engage and possibly mobilize the wider community. Through the grassroots activist lens, the business community represents merely part of the stage setting. Corporate decision makers are not a target audience but purely ‘props’ that are being utilized to emphasize the humor inherent in a given action or situation.

Limitations

As an exploratory, single case study, this study has a number of limitations. Its insight is limited to one activist group, during a given period of time, within one cultural and economic context. Due to the focus on a specific research setting, the generalizability of this case study is limited. However, humorous, street theater inspired actions are not unique to (Western) Australia. Readers may be able to relate some elements of this case study to their own observations in different cultural contexts. Furthermore, due to space limitations this chapter does not provide detailed examples of the data itself, but rather presents conclusions drawn from the data available. Observations at actions and planning meetings, as well as the use of a reflective research diary provided the broader context that informed many of the interpretations and assumptions on which this chapter is based. This study provides a snapshot of what I as a researcher observed and experienced during the time of data collection. I acknowledge that many conversations and examples of communication would have taken place without my presence. Furthermore, the findings and in particular my conclusions rely on my personal ability as a researcher, as well as my own identity and cultural background (intersubjectivity). However, it is my actual presence and participation as a researcher that characterize this study and have enabled me to gain first-hand insights into grassroots activism from the activist point of view in the first place, thereby enabling me to provide an alternative viewpoint that challenges the extant body of knowledge. Strategies have been put in place to ensure the quality of the research findings. Further research based on different contexts, issues and groups is needed to confirm findings and conclusions drawn regarding the role of humor—and consequently the nature of the activist–organization relationship.

p.53

References

1 E.g. Bogad, L. M. (2010). Carnivals against capital: Radical clowning and the global justice movement. Social Identities, 16(4), 537–557; Bruner, M. L. (2005). Carnivalesque protest and the humorless state. Text and Performance Quarterly, 25(2), 136–155; Chvasta, M. (2006). Anger, irony, and protest: Confronting the issue of efficacy, again. Text and Performance Quarterly, 26(1), 5–16; Shepard, B. H. (2011). Play, Creativity, and Social Movements: If I Can’t Dance, It’s Not My Revolution (Vol. 57). New York: Routledge; Weissberg, R. (2005). The Limits of Civic Activism: Cautionary Tales on the Use of Politics. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

2 Killeen, M. E. (1991). Clinical clowning: Humor in hospice care. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 8(3), 23–27; Mancke, R. B., Maloney, S., & West, M. (1984). Clowning: A healing process. Health Education, 15(6), 16–18; Schamberger, M. (2014). Compassionate clowning: Improving the quality of life of people with dementia. In S. Shea, R. Wynyard, & C. Lionis (Eds.), Providing Compassionate Healthcare: Challenges in Policy and Practice (pp. 139–154). Oxon: Routledge.

3 Grunig, op. cit.

4 See e.g. Smith, M. F., & Ferguson, D. P. (2001). Activism. In L. H. Robert (Ed.), Handbook of Public Relations (pp. 291–300). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

5 E.g. Bunting, M., & Lipski, R. (2001). Drowned out? Rethinking corporate reputation management for the Internet. Journal of Communication Management, 5(2), 170–178; Deegan, D. (2001). Managing Activism: A Guide to Dealing with Activists and Pressure Groups. London: Kogan Page; Grunig, L. A. (1992). Activism: How it limits the effectiveness of organizations and how excellent public relations departments respond. Excellence in Public Relations and Communication Management (pp. 503–530). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; John, S., & Thomson, S. (2003). New Activism and the Corporate Response. London: Palgrave Macmillan; Turner, M. M. (2007). Using emotion in risk communication: The anger activism model. Public Relations Review, 33(2), 114–119; Werder, K. P. (2006). Responding to activism: An experimental analysis of public relations strategy influence on attributes of publics. Journal of Public Relations Research, 18(4), 335–356.

6 See e.g. Stokes, A. Q., & Rubin, D. (2010). Activism and the limits of asymmetry: The public relations battle between Colorado GASP and Philip Morris. Journal of Public Relations Research, 22(1), 26–48; Weaver, C. K. (2010). Carnivalesque activism as a public relations genre: A case study of the New Zealand group Mothers Against Genetic Engineering. Public Relations Review, 36(1), 35–41.

7 Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (2007). It’s Not Just PR: Public Relations in Society. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; Dozier, D. M., & Lauzen, M. M. (2000). Liberating the intellectual domain from the practice: Public relations, activism, and the role of the scholar. Journal of Public Relations Research, 12(1), 3–22; Jones, R. (2002). Challenges to the notion of publics in public relations: Implications of the risk society for the discipline. Public Relations Review, 28(1), 49–62.

p.54

8 Meyer, J. C. (2000). Humor as a double-edged sword: Four functions of humor in communication. Communication Theory, 10(3), 310–331, p. 328.

9 Vuorela, T. (2005). Laughing matters: A case study of humor in multicultural business negotiations. Negotiation Journal, 21(1), 105–130.

10 Lyttle, J. (2001). The effectiveness of humor in persuasion: The case of business ethics training. The Journal of General Psychology, 128(2), 206–216.

11 Duncan, W. J., & Feisal, J. P. (1989). No laughing matter: Patterns of humor in the workplace. Organizational Dynamics, 17(4), 18–30.

12 Vuorela, op. cit.

13 Meyer, op. cit.

14 Cline, T. W., & Kellaris, J. J. (1999). The joint impact of humor and argument strength in a print advertising context: A case for weaker arguments. Psychology & Marketing, 16(1), 69–86.

15 Lyttle, op. cit.

16 Vuorela, op. cit.

17 Rogerson-Revell, P. (2007). Humour in business: A double-edged sword: A study of humour and style shifting in intercultural business meetings. Journal of Pragmatics, 39(1), 4–28.

18 Holmes, J., & Marra, M. (2002). Having a laugh at work: How humour contributes to workplace culture. Journal of Pragmatics, 34(12), 1683–1710.

19 See e.g. Rogerson-Revell, op. cit.

20 Chiaro, D. (1992). The Language of Jokes: Analyzing Verbal Play. London: Routledge; Curtin, P. A., & Gaither, T. K. (2007). International Public Relations: Negotiating Culture, Identity and Power. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing; Holmes, J., & Hay, J. (1997). Humour as an ethnic boundary marker in New Zealand interaction. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 18(2), 127–151.

21 Meyer, op. cit.

22 Rogerson-Revell, op. cit.

23 Rogerson-Revell, op. cit.

24 Meyer, op. cit.

25 Branagan, M. (2007). The last laugh: Humour in community activism. Community Development Journal, 42(4), 470–481, p. 470.

26 Hart, M., & Bos, D. (Eds.). (2007). Humour and Social Protest (Vol. 15). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

27 Lievrouw, L. A. (2011). Alternative and Activist New Media. Cambridge: Polity Press.

28 Bruner, op. cit.; Hart, & Bos, op. cit.

29 Smith & Ferguson, op. cit.

30 Glaser, B. G. (1998). Doing Grounded Theory: Issues and Discussions. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

31 Daymon, C., & Holloway, I. (2011). Qualitative Research Methods in Public Relations and Marketing Communications (2nd ed.). Oxon: Routledge, p. 115.

32 Kearns, B. (2004). Stepping Out for Peace – A History of CANE and PND (WA). Perth, Australia: People for Nuclear Disarmament.

33 Murray, S. (2006). ‘Make pies not war’: Protests by the women’s peace movement of the mid 1980s. Australian Historical Studies, 37(127), 81–94; Wittner, L. S. (2009). Nuclear disarmament activism in Asia and the Pacific, 1971–1996. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 25.

34 World Nuclear Association. (2016, May 22, 2015). World Uranium Mining Production. Retrieved March 11, 2016, from http://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/mining-of-uranium/world-uranium-mining-production.aspx.

35 World Nuclear Association. (2016, February 2016). Australia’s uranium. Retrieved March 19, 2016, from http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/inf48.html.

36 Towie, N. (2010, February 1). Great science debates of the next decade: Spotlight on uranium. Perth Now; Switkowski, Z. (2009, December 3). Australia must add a dash of nuclear ambition to its energy agenda. Sydney Morning Herald.

p.55

37 O’Brien, A. (2011, August 6). Boom economy starts to feel spreading gloom. The Australian. Retrieved from http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/boom-economy-starts-to-feel-spreading-gloom/story-fn59niix-1226108821447.

38 Wolf, K. (2014). Beyond the corporate lens: The use of humour in activist communication. In L. Lievrouw (Ed.), Communication Yearbook: Challenging Communication Research (Vol. 38, pp. 91–105). New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

39 Online news articles have since been removed by the relevant news organization, as news items are archived on a regular basis. The author has set up her own news and social media archive for research purposes.

40 Chiaro, op. cit.; Rogerson-Revell, op. cit.

41 Burns, L., Marra, M., & Holmes, J. (2001). Women’s humour in the workplace: A quantitative analysis. Australian Journal of Communication, 28(1), 83; Rogerson-Revell, op. cit.

42 See e.g. Bruner, op. cit.; Hart, & Bos, op. cit.; Weaver, op. cit.

43 Lyttle, op. cit.; Vuorela, op. cit

44 Lyttle, op. cit.; Vuorela, op. cit.

45 Rogerson-Revell, op. cit.; Vromen, A., & Collin, P. (2010). Everyday youth participation? Contrasting views from Australian policymakers and young people. Young, 18(1), 97–112.

46 Holmes, & Marra, op. cit.; Holmes, J. (2000). Politeness, power and provocation: How humour functions in the workplace. Discourse Studies, 2(2), 159–185.

47 Rogerson-Revell, op. cit.

48 Hart, & Bos, op. cit.

49 Meyer, op. cit.

50 Holmes, J., & Hay, J. (1997). Humour as an ethnic boundary marker in New Zealand interaction. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 18(2), 127–151.

51 Taecharungroj, V., & Nueangjamnong, P. (2015). Humour 2.0: Styles and types of humour and virality of memes on Facebook. Journal of Creative Communications, 10(3), 288–302.

52 Botha, E. (2014). A means to an end: Using political satire to go viral. Public Relations Review, 40(2), 363–374.

53 Footprints4Peace. (2012, November 28). Toro Energy Clean Up AGM. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AAL-BJCOUQU.

54 E.g. Smith, & Ferguson, op. cit.; Grunig, J. E., & Grunig, L. A. (1997). Review of a program of research on activism: Incidence in four countries, activist publics, strategies of activist groups and organisational responses to activism. Paper presented at the Fourth Public Relations Research Symposium, Managing Environmental Issues, Lake Bled, Slovenia July 11–13.