p.99

Daniel Putz and Tabea Scheel

Theory

Major parts of today’s economy are based on service jobs that include the deliberate regulation of emotions during customer contact. Organizations aim at creating pleasant customer interactions in order to provoke desirable reactions (e.g., higher turnover, less cancellations and complaints) that may ensure and increase commercial success. At the same time, employees are often challenged with stressful job demands that may impair their subjective well-being and their actual capability to shape customer relations in a positive way. Therefore, the aim of the present study is to investigate the relationship between job demands and the quality of customer contact. Specifically, we investigate how time pressure is related to the adoption of positive and negative humor in interactions with retail customers, and whether the emotion work strategies of deep and surface acting mediate these relationships.

Given the focus on humor in the communication between employee and customer, our research is in line with humor definitions as a communicative activity. For instance, Romero and Cruthirds (2006) defined humor as amusing communications that create a positive cognitive and emotional reaction in a person or a group.1 In addition, we differentiate between the potentially positive and negative sides of humor, thus following the humor styles introduced by Martin et al.2 They conceptualized two positive (i.e., affiliative, self-enhancing) and two negative styles (i.e., aggressive, self-defeating) of using humor in everyday life. Given our focus on interpersonal communication, our positive and negative humor use in customer contact mirror other-directed humor, i.e., the affiliative and the aggressive styles.

The role of humor in customer contact

The creation of positive mood during customer contact may be regarded as a pivotal task of employees in customer service. Pleasant interactions with employees are likely to increase customer satisfaction, loyalty and recommendations.3 The global PwC Total Retail Survey 2016 with nearly 23,000 participants from 25 countries highlights the relevance of satisfying customer contacts: with 40% approval, sales associates were qualified as the most relevant factor to increase in-store experience.4 The creation of positive customer contacts may be among the most promising factors to face one of the main challenges for retailers today: operators of department stores and local shops are struggling to gain and secure customers and sales, while mobile and e-commerce offer permanent access to cheaper and more convenient purchasing opportunities.5 Thus, service providers are faced with the question of how their employees can evoke and maintain comfortable feelings during customer contact. One effective way to do so may be the purposeful use of humor, which can be regarded as “amusing communications that produce positive emotions and cognitions in the person, group or organization.”6 Accordingly, service employees may smile to customers and banter with them during sales talks in order to create an enhancing and affiliative atmosphere. However, humor may also be used in a more negative way, such as mocking and making fun of customers, and can therefore also impair the quality of customer relations through aggressive or deprecating behaviors.7 Thus, Martineau8 stated that depending on the kind of humor used, it can both function as a social “lubricant,” fostering closeness to other people and increasing social support, or as an “abrasive,” creating a hostile atmosphere and disintegrating relationships. This differentiation between desired and undesired kinds of humor raises the question of what increases the likelihood of employees applying positive humor and avoiding negative humor in customer contact.

p.100

Time pressure threatens the purposeful adoption of humor in customer contact

The purposeful use of humor in customer contact involves a number of self-regulatory activities, such as:

• monitoring and interpreting the characteristics, behavior and emotional state of customers for potential links for jokes and their receptivity to humorous interactions in a given situation;

• keeping up professional communication while preparing for an amusing statement or action;

• adopting them at the right time and in an appropriate application rate to develop its humorous potential for the self and the other; and

• regulating one’s own feelings in order to prevent the adoption of negative humor (e.g., by reducing annoying or aggressive impulses) and to facilitate positive humor (e.g., lightening up one’s mood).

According to the Ego Depletion Theory,9 stressful job demands reduce employees’ self-regulatory resources and may therefore influence the adoption of humor. For instance, customer contact is often characterized by subjective time pressure. Customer requests can occur suddenly at any time during operating hours and are usually expected to be tended to immediately regardless of whether the responsible employee has other work obligations or not. Thus, “the sense that one’s duties and responsibilities exceed one’s ability to complete them in the time available”10 is likely to occur and will permanently redirect a certain amount of employees’ regulatory resources from current customer interactions to the monitoring of concurrent requirements and the preparation for future tasks. Due to the reduced amount of resources available, employees pressed for time may lack the essential attention and readiness to express a witticism with a right timing to make the customer laugh and to brighten up the atmosphere, or may fail to suppress an ironic reply or cynical remark that may harm or annoy a customer. Furthermore, the ongoing consumption of self-regulatory resources caused by stressful job demands such as time pressure is regularly accompanied by impairments in subjective well-being and increases in affective irritation.11 This results in a prevailing mood readily accessible for aggressive and deprecating impulses. Employees need to actively suppress these emotions in order to enable affiliative and pleasant interactions. We therefore assume that time pressure impairs employees’ ability to adopt humor in a functional way through the delimitation of self-regulatory resources and the impairment of subjective well-being resulting in less positive and more negative humor.

p.101

Hypothesis 1: Time pressure will be (a) negatively related to the adoption of positive humor and (b) positively related to the adoption of negative humor in customer contact.

Emotion work strategies mediate the effects of time pressure on humor

In modern service societies, emotion work, that is, the “emotional regulation [. . .] in the display of organizationally desired emotions”12 has become a central job requirement for many employees. Customer contact is to be regarded as a prototypical type of emotion labor, requiring employees to actively regulate their emotions in order to display emotions that are desired by the organization and the customers. This involves ongoing self-regulatory activities, such as:

• understanding a client’s emotional situation;

• activating the relevant social rules that determine which emotions should be suppressed or evoked in the given situation;

• perceiving one’s own actual emotional state; and

• coping with the demand to suppress or amplify one’s actual feelings or to express diverging emotions.13

Employees may apply different strategies in order to regulate their emotions, and these emotion work strategies may be one of the mechanisms linking time pressure to employees’ adoption of humor in customer contact.

There are at least two distinct strategies to shape apparent emotions in a desired way: employees may either modify their facial expressions without regard to their actual emotional experience (“surface acting,” e.g., smiling while feeling sad) or they may try to influence their inner feelings in a way that their emotional experience fits the requested emotional expression (“deep acting,” e.g., cheering oneself up when being sad).14 While surface acting refers to a behavioral strategy of changing emotional expression, deep acting attempts to adjust the emotional experience itself. As such, surface and deep acting do not only describe certain ways of adjusting emotional expressions, they also refer to different stages in the development of emotional experience.15

Deep acting aims at aligning a person’s true feelings to the situational requirements before emotional cues can elicit behavioral, experiential, or physiological response tendencies.16 Thus, deep acting can be regarded as an antecedent-focused emotion regulation strategy, i.e., a strategy that is applied very early in the timeline of the emotion process before an emotion entirely develops its experiential and behavioral potential. When a person becomes aware of an inconsistency between the emotional reactions directly provoked by situational cues and the emotional reactions required in the very same situation, he or she may engage in deep acting. This may be addressed in three ways:

p.102

• by changing the situation (e.g., addressing an annoyed customer in a different way in order to reduce his or her anger and to induce more positive reactions);

• by changing the perception of the situation by refocusing attention on situational aspects or thoughts more consistent with the required emotional reaction (e.g., focusing on the spending capacity of a rude and demanding customer or remembering the last pleasant interaction with a client); or

• by reappraising the situation (e.g., reframing the customer interaction as an opportunity to learn how to deal with challenging interaction situations which may increase sales counts in the long run rather than viewing it as a critical situation to immediately increase poor sales counts).17

As a consequence of these deep acting strategies, emotional experience is redirected in the desired way, thus immediately resolving the emotional conflict and triggering the required emotional expressions. People who tend to engage in deep acting report less negative feelings and show fewer expressions of negative affect while positive emotional experience and expressions are increased,18 most likely resulting in a corresponding pattern of less adoption of negative humor and more use of positive humor in customer contact. Empirical studies show that deep acting is associated with closer and more positive interpersonal relations19 as well as higher job satisfaction, emotional performance and customer satisfaction.20 Accordingly, we assume deep acting to be positively related to the adoption of positive humor in customer contact.

While deep acting appears to be beneficial for the person and the organization, its effective adoption requires the person to immediately sense and rapidly react to the very onset of emotional conflicts in order to selectively redirect attention, reinterpret information, and inhibit emotional stimuli before emotional experience unfolds. Accordingly, Gross and John suggested that “occasionally, there may not be time to cognitively reevaluate a rapidly developing situation, making reappraisal an unworkable choice.”21 Especially under time pressure, when employees are occupied with several tasks simultaneously, the opportunity to perceive and respond to the development of undesired emotions is limited, thereby increasing the risk of missing the very limited time frame when deep acting can be effectively applied. We therefore assume that higher time pressure will be associated with less engagement in deep acting.

In contrast, surface acting describes a response-focused strategy of emotion regulation that can be applied rather late in the timeline of the emotion process. When an emotion has already developed and the person experiences an inconsistency between the expressive reactions associated with the actual emotional experience and the situational requirements, surface acting aims at suppressing undesired automatic reactions while amplifying or faking desired emotional expressions. Thus, surface acting enables people to manage emotional expression without adjusting their actual feelings22 and may also be applied when the opportunity to deep act was missed. Time pressure should therefore increase the likelihood of surface acting.

p.103

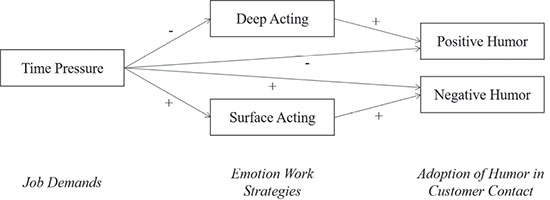

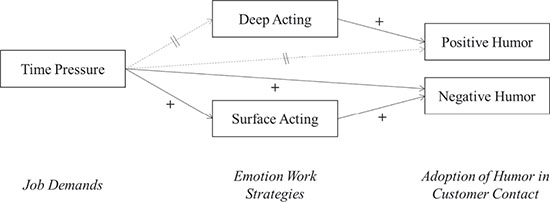

Figure 3.3.1 Research model

Employees engaging in surface acting may be effective in masking negative feelings, but the negative experience itself remains unchanged and the emotional conflict between actual feelings and requested emotions persists, thus continuing to provoke undesired emotional reactions that need to be countered by further emotional regulation. Surface acting therefore permanently consumes cognitive resources to effortfully manage emotion response tendencies. Furthermore, while employees engage in surface acting the ongoing discrepancy between inner feelings and observable behavior is likely to trigger feelings of inauthenticity that also need to be countered by active emotional regulation, further reducing the capability to effectively manage the emotional expression, interpersonal behavior and performance. In fact, people who tend to engage in surface acting not only report less positive affect and show less positive expressions but also experience higher levels of negative emotions resulting in less close and less positive interpersonal relations.23 Furthermore, a meta-analysis by Huelsheger and Schewe24 showed surface acting to be positively associated with burnout and strain and negatively related to job satisfaction and emotional performance. Accordingly, we assume that surface acting will increase the likelihood of negative humor use.

Altogether, we assume a mediating role of employees’ emotion work strategies for the link between time pressure and humor use with customers. Our hypotheses are summarized in Figure 3.3.1.

Hypothesis 2: The relationship between time pressure and humor use in customer contact will be mediated by (a) deep acting for the adoption of positive humor and (b) surface acting for the adoption of negative humor in customer contact.

Method

Participants and procedure

We conducted a cross-sectional, quantitative study at four German retail stores in order to test our hypotheses.25 Complete surveys of 170 employees were obtained (70.8% response rate). Surveys were administered personally to employees, completed during work time, and immediately collected. Anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed.

Fifty-six participants were women (32.9%), and 106 were men (62.4%). Most of the participants were between 21 and 30 (n = 68, 40%) or 31 and 40 years of age (n = 56, 32.9%), nine were between 16 and 20 (5.3%), 26 were between 41 and 51 (15.3%), seven were between 51 and 60 (4.1%), and four were older than 60 (2.4%). Participants had worked in retail for an average of 11.4 years (SD = 8.1).

Measures

Time pressure

Time pressure was measured with the four-item subscale from the Instrument for Stress-Oriented Analysis of Work (ISTA)26 on a 5-point Likert scale. Two questions (e.g., “How often are you pressed for time?”) were rated as 1 (very rarely/never), 2 (rarely/approximately once a week), 3 (occasionally/approximately once a day), 4 (frequently/several times a day), or 5 (very often/almost continuously). The answer choices differed for two questions: The question “How often do you have to delay or cancel your break due to too much work?” were rated as 2 (rarely/approximately once a month), 3 (occasionally/approximately once a week), 4 (frequently/several times a week), or 5 (very often/daily). The question “How often do you have to leave work later than planned due to too much work?” differed from the previous question in the anchors for the ratings of 3 (occasionally/several times a month) and 5 (very often/almost daily). Cronbach’s alpha was .71.

p.104

Emotion work

Deep acting and surface acting were assessed with three items each.27 A sample item for deep acting is “I try to actually experience the emotions that I must show” and for surface acting “I try to hide my true feelings.” The items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale as 1 (seldom/never), 2 (seldom/several times month), 3 (occasionally/several times a week), 4 (often/daily), and 5 (very often/several times a day). Cronbach’s alpha was .75 for deep acting and .82 for surface acting.

Adoption of humor in customer contact

Four questions had to be answered for positive humor in customer contact, and two questions for negative humor with customers. The questions were rated on the same 5-point Likert scale as applied for emotion work. For instance, participants were asked to answer “How often do you joke with the customers in a sales conversation?” (adoption of positive humor) or “How often do you poke fun at customers, directly in sales conversation?” (adoption of negative humor). Cronbach’s alpha was .70 for positive humor with customers and the correlation of the two items of negative humor with customers was r = .52 (p < .01).

Control variable

As the adoption of emotion work strategies is likely to change with ongoing work experience, we controlled deep acting and surface acting for participant’s tenure in retail.

Analyses

In order to test our assumptions that time pressure is related to the adoption of certain kinds of humor in customer service and that this relationship is mediated by emotion work strategies, we used Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression-based mediation-analysis with bootstrapping provided by the PROCESS software for SPSS.28 PROCESS estimates the indirect effect of the predictor on the dependent variable through the mediator. If emotion work strategies mediate the effects of time pressure (predictor) on the kind of humor used in customer contact (criterion), this indirect effect becomes significant. PROCESS only provides unstandardized estimates. Therefore, we z-standardized all variables before entering them into the mediation analyses in order to facilitate interpretation of effects. In case of significant mediation, the amount of variance explained through the mediation process can be quantified by comparing the indirect effect to the direct effect of time pressure on the kind of humor used without taking emotion work strategies into account.

p.105

Results

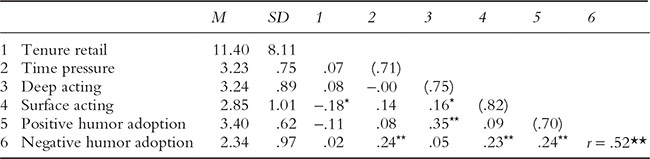

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations for all variables are displayed in Table 3.3.1. Emotion work strategies show the assumed relations with the adoption of humor in customer contact with positive associations between deep acting and the adoption of positive humor (r = .35; p < .01) and surface acting and the adoption of negative humor (r = .23; p < .01). The associations of time pressure with emotion work strategies were less distinct: time pressure was positively associated with the adoption of negative humor in customer contact (r = .24; p < .01). Although the correlation coefficient for time pressure and surface acting was also numerically positive it did not become significant (r = .14; ns). There was no direct association between time pressure and either the adoption of positive humor (r = .08; ns) or deep acting (r = .00; ns).

Table 3.3.1 Descriptive statistics and correlations between the variables

Note: N = 169–170. Pearson correlations, two-sided. Reliabilities (Cronbach’s α) are on the diagonal in parentheses. *p < .05. **p < .01.

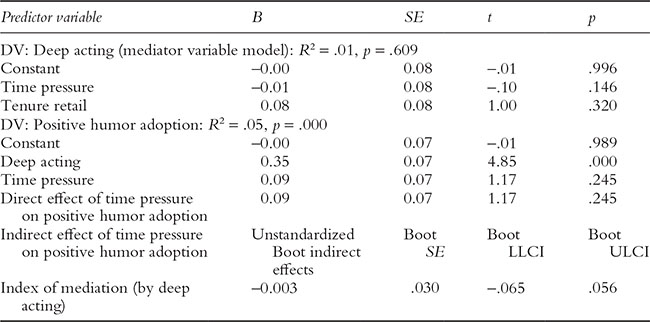

To test our hypotheses on the mediating effects of emotion work strategies, we estimated a mediation model29 using 1,000 bootstrap samples and 95% bias-corrected bootstrap Confidence Intervals (CIs) for all indirect effects. Results support our assumption that emotion work strategies are associated with the adoption of humor in customer contact after controlling for tenure. Deep acting was positively related to positive humor use (B = .35, SE = .07, p ≤ .001; Table 3.3.2). However, as for the zero-order correlations, time pressure was not related to either positive humor (direct effect = .09, ns, 95% CI [−.059, .229]) or deep acting (B = −.01, SE = .08, ns). Accordingly, the indirect effect was not significant (indirect effect = -.003, SE = .03, 95% CI [-.065, .056]). Thus, hypotheses 1a and 2a were not supported (see Table 3.2.2).

Table 3.3.2 Results of mediation-analysis of deep acting mediating the relationship between time pressure and adoption of positive humor (hypotheses 1a and 2a)

Note: Listwise N = 169. All variables are z-standardized. DV = dependent variable. LL = lower limit. CI = confidence interval. UP = upper limit. Bootstrap sample size = 1,000. CI = 95%.

p.106

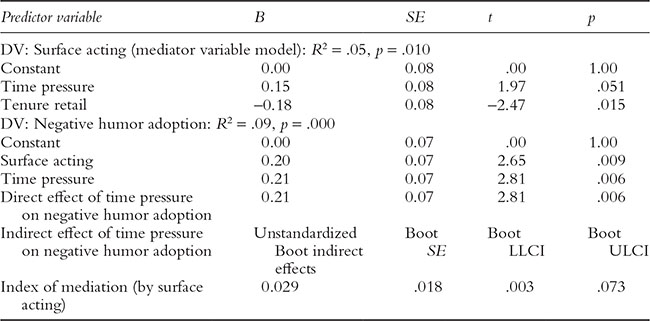

Table 3.3.3 Results of mediation-analysis of surface acting mediating the relationship between time pressure and adoption of negative humor (hypotheses 1b and 2b)

Note: Listwise N = 170. All variables are z-standardized. DV = dependent variable. LL = lower limit. CI = confidence interval. UP = upper limit. Bootstrap sample size = 1,000. CI = 95%.

Time pressure was directly related to negative humor use (direct effect = .20, p ≤ .01, 95% CI [.062, .356]), and this association was partially mediated by surface acting (Table 3.3.3). Time pressure was significantly positively related to surface acting (B = .15, SE = .08, p = .051), and surface acting was positively associated with negative humor use (B = .20, SE = .07, p ≤ .01). The indirect effect was significant (indirect effect = .03, SE = .02, 95% CI [.003, .073]) and accounted for 13.8% of the direct effect of time pressure on negative humor use in customer contact. Thus, hypotheses 1b and 2b were supported by the results (see Table 3.3.3).

Discussion

In our study we investigated the relationship between time pressure, emotion work strategies and the use of positive and negative humor in customer contact on a cross-sectional retail sample. The results are summarized in Figure 3.3.2.

Figure 3.3.2 Summary of results

p.107

First of all, we assumed that the strategies of surface and deep acting influence the kind of humor adopted during customer contact, which was supported by the results of the survey. Deep acting seems to foster pleasant customer relations through affiliative and enhancing humor use while surface acting seems to challenge positive customer interactions through deprecating and aggressive humor use. Therefore, our findings correspond well to the theoretical assumptions and well-established empirical findings on the effects of emotion work strategies on employees’ emotional experience, performance and customer satisfaction30 and add further support for the beneficial effects of deep acting and the undesirable effects of surface acting on interpersonal performance in customer service.

Furthermore, our results support our assumption that time pressure increases the likelihood that employees will engage in surface acting which in turn is associated with a higher tendency to adopt negative humor in customer contact. These findings are in line with Ego Depletion Theory31 which predicts that time pressure disrupts employees’ capability to purposefully adopt humor in customer contact due to an increased need for and consumption of self-regulatory resources accompanied by impairments of subjective well-being and higher levels of affective irritation. However, we found no negative effects of time pressure on either deep acting or on the adoption of positive humor in customer contact. Thus, time pressure seems to increase the likelihood of dysfunctional strategies of emotional regulation, while leaving the tendency of deep acting rather unaffected. These differential effects of time pressure on deep and surface acting may be attributed to different levels of conscious control required by the emotion work strategies. While surface acting always involves deliberate monitoring of one’s own emotional experience and purposeful regulations of emotional expression in order to fit situational demands, deep acting may develop into an automatic reaction to emotional conflict through processes of instrumental learning, also referred to as passive deep acting.32 This may explain why there was no relationship between time pressure and deep acting in our sample, and could also indicate that in contrast to surface acting deep acting may be largely unaffected by stressful work demands in general.

Conclusions and managerial implications

Based on the beneficial effects of deep acting on the adoption of positive humor, we suggest that service providers should support their employees to develop and apply deep acting behaviors (e.g., through supervisor’s feedback and behavior modeling, trainings and coaching). Such interventions may increase the likelihood of deep acting even in stressful work situations since deep acting was unrelated to time pressure in our sample. Deep acting may be even more effective than surface acting when employees’ resources are stressed by high work demands as some authors have suggested that deep acting may require less regulatory resources.33 Since surface acting keeps the original emotional experience intact, it constantly consumes regulatory resources in order to disconnect the emotional expression from the inner feelings. In contrast, deep acting is proposed to require less regulatory resources, because once the emotional experience is aligned to the situational demands, there is no further need to purposefully influence the emotional display. Thus, applying the emotion work strategy of deep acting may restrict employees’ resources for shorter terms and to a lesser degree than surface acting, enabling them to quickly refocus their attention and efforts to the creation of pleasant customer interactions.

p.108

Nevertheless, time pressure appears to impair the quality of customer contact through an increased likelihood of surface acting and negative humor use. Thus, employees should not only be qualified in deep acting but should also be encouraged to prefer deep acting strategies over surface acting when situational demands may provoke the adoption of the latter. Over and above the effects on the adoption of humor, deep acting may be more effective in provoking desired effects on customers than surface acting. Organizational rules for emotional display are often based on the assumption that certain emotional expressions will result in desired customer reactions (e.g., higher sales by friendly shop assistants, less cancellations and complaints about sympathetic insurance salesmen). However, research shows that positive emotional expressions only evoke positive reactions to the extent that they are perceived as authentic.34 Since surface acting results in inauthentic emotional displays, organizational interventions should aim at promoting the adoption of deep acting which involves authentic expressions of emotions and supports positive interactions between employees and customers.

Limitations and recommendations for future research

Our results are based on a cross-sectional sample from a German retail company. Thus, they do not allow for causal interpretations and generalizability is restricted. Future studies should test our theoretical model in longitudinal designs, such as diary studies, and larger as well as more diverse samples. Including nearly three quarters of the entire staff of four retail stores, our sample is likely to reliably represent a major industrial sector of service work. However, there are other fields of work requiring employees to deliberately regulate their emotions in different ways, which may also include the suppression of affiliative emotional expressions (e.g., security agents required to appear repellent rather than kind, debt collectors who have to control their sympathy and compassion for debtors, judges who are expected to remain unaffected by emotions of defendants and witnesses). It is reasonable to assume that these diverging demands will affect the adoption and effects of emotion work strategies and humor in service interactions. Replication studies should also introduce and evaluate more reliable scales for measuring the adoption of humor in customer contact. We assessed time pressure and emotion work strategies through well-established scales that also proved to be sufficiently reliable in our sample. Since there was no evaluated scale in the literature we tried to capture humor adoption through self-constructed items that showed an acceptable reliability for positive humor and a positive correlation between the items capturing the adoption of negative humor. We therefore assume that our items can be interpreted as a general indicator of humor use. Further investigations of the adoption of humor in customer contact and the integration of results will nevertheless benefit from more elaborated models and empirical measures that could for instance apply models of individual humor styles35 to customer interaction. For instance, sense of humor as well as the self-enhancing humor style are associated with amusement by the incongruences of life (including adversities), i.e., these kinds of humor help people to distance themselves from problems in stressful situations. Thus, self-enhancing humor could be an effective coping strategy for employees during stressful periods of (emotion) work. Also important for future research is the inclusion of customer ratings or mystery shopping results in order to test whether customers actually perceive a similar type of humor as rated by the employee, and whether specific kinds of humor are actually related to (un)favorable customer reactions. Replications and extensions of our findings would allow for causal interpretations and generalization of effects and would therefore offer a solid framework for the design and implementation of effective intervention strategies to foster positive customer relations through the purposeful use of humor.

p.109

References

1 Romero, E. J., & Cruthirds, K. W. (2006), The use of humor in the workplace. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(2), 58–69.

2 Martin, R. A., Puhlik-Doris, P., Larsen, G., Gray, J., & Weir, K. (2003), Individual differences in uses of humor and their relation to psychological well-being: Development of the Humor Styles Questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(1), 48–75.

3 Fisher, M. L., Krishnan, J., & Netessine, S. (2006), Retail Store Execution: An Empirical Study. Philadelphia, PA: The Wharton School. http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/13361.pdf [Accessed October 26, 2016].

4 PwC (2016), They say they want a revolution. Total Retail 2016. http://pwc.com/totalretail [Accessed October 26, 2016].

5 MacKenzie, I., Meyer, C., & Noble, S. (2013), How retailers can keep up with consumers. McKinsey Quarterly. http://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/how-retailers-can-keep-up-with-consumers [Accessed October 26, 2016].

6 Romero, E. J., & Cruthirds, K. W. (2006), The use of humor in the workplace. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(2), 58–69; p. 59.

7 Martin, R. A., Puhlik-Doris, P., Larsen, G., Gray, J., & Weir, K. (2003), Individual differences in uses of humor and their relation to psychological well-being: Development of the Humor Styles Questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(1), 48–75.

8 Martineau, W. H. (1972), A model of the social functions of humor. In J. Goldstein, & P. McGhee (Eds.), The Psychology of Humor (pp. 101–125). New York: Academic Press.

9 Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998), Ego-depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1252–1265; Muraven, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000), Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 247–259.

10 Kleiner, S. (2014), Subjective time pressure: General or domain specific? Social Science Research, 47, 108–120; p. 108.

11 De Jonge, J., & Dormann, C. (2006), Stressors, resources and strains at work: A longitudinal test of the Triple Match Principle. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1359–1374.

12 Zapf, D., Vogt, C., Seifert, C., Mertini, H., & Isic, A. (1999), Emotion work as a source of stress: The concept and development of an instrument. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8, 371–400; p. 371.

13 Zapf et al., op. cit.

14 Grandey, A. A. (2000), Emotion regulation in the work place: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 95–110.

15 Gross, J. J. (1998), The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2, 271–299.

16 Gross, op. cit.

17 Grandey, op. cit.

18 Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003), Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 348–362.

19 Gross & John, op. cit.

20 Huelsheger, U. R., & Schewe, A. F. (2011), On the costs and benefits of emotional labor: A meta-analysis of three decades of research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(3), 361–389.

21 Gross & John, op. cit.; p. 361.

22 Grandey, op. cit.

p.110

23 Gross & John, op. cit.

24 Huelsheger & Schewe, op. cit.

25 See also Scheel, T., Putz, D., & Kurzawa, C. (2017), Give me a break: Laughing with colleagues guards against ego depletion. European Journal of Humour Research, 5(1), 36–51.

26 Semmer, N. K., Zapf, D., & Dunckel, H. (1999), Instrument zur Stressbezogenen Tätigkeitsanalyse (ISTA) [Instrument for stress-related job analysis (ISTA)]. In H. Dunckel (Ed.), Handbuch psychologischer Arbeitsanalyseverfahren (pp. 179–204). Zürich: vdf Hochschulverlag.

27 Brotheridge, C. M., & Grandey, A. A. (2002), Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspectives of “people work.” Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60, 17–39.

28 Hayes, A. F. (2015), The PROCESS macro for SPSS and SAS. Retrieved on January 26, 2015, from http://www.processmacro.org/download.html.

29 Model 4 of Hayes PROCESS macro, op. cit.

30 Huelsheger & Schewe, op. cit.; Grandey, op. cit.

31 Muraven & Baumeister, op. cit.

32 Zapf, D. (2002), Emotion work and psychological wellbeing: A review of the literature and some conceptual considerations. Human Resource Management Review, 12, 237–268.

33 Totterdell, P., & Holman, D. (2003), Emotion regulation in customer service roles: Testing a model of emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 8, 55–73.

34 Grandey, A. A., Fisk, G. M., Mattila, A. S., Jansen, K. J., & Sideman, L. A. (2005a), Is “service with a smile” enough? Authenticity of positive displays during service encounters. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 96, 38–55.

35 Martin et al., op. cit.