4

Utilitarianism

4.1 Revealed Preference in Social Choice

Until relatively recently, it was an article of faith among economists that one can’t make meaningful comparisons of the utilities that different people may enjoy. This chapter is a good one to skip if you don’t care about this question.

Social choice. The theory of social choice is about how groups of people make decisions collectively. This chapter is an aside on the implications of applying the theory of revealed preference to such a social context. Even in the case of a utilitarian government, we shall therefore be restricting our attention to notions of utility that make it fallacious to argue that policies are chosen because they maximize the sum of everyone’s utility. On the contrary, we assign a greater utility to one policy rather than another because it is chosen when the other is available.

The theory of revealed preference is orthodox in individual choice, but not in social choice. However, no new concepts are required. If the choices made collectively by a society are stable and consistent, then the society behaves as though it were seeking to maximize something or other. The abstract something that it seems to be trying to maximize is usually called welfare rather than utility in a social context.

There are two reasons why it may be worth trying to figure out the welfare function of a society. The first is that we may hope to predict collective choices that the society may make in the future. The second is that bringing a society’s welfare function to the attention of its citizens may result in their taking action to alter how their society works. For example, it may be that fitting a utilitarian welfare function to the available data is only possible if girls are treated as being worth only half as much as boys. Those of us who don’t like sexism would then have a focus for complaint.

Difficulties with such an approach are easy to identify. What justifies the interpersonal comparisons of utility that are necessary for anything useful to emerge? Why should we imagine that even a rational society would have the consistent preferences we attribute to rational individuals?

4.1.1 Condorcet’s Paradox

Thomas Hobbes’ (1986) Leviathan treats a society like a single person written large. Karl Marx (Elster 1985) does the same for capital and labor. But a democratic society isn’t a monolithic coalition that pursues its goals with the same single-minded determination as its individual citizens. The decisions it makes reflect a whole raft of compromises that are necessary to achieve a consensus among people with aspirations that will often be very different.

Condorcet’s paradox of voting shows that a society which determines its communal preferences from the individual preferences of its citizens by honest voting over each pair of alternatives will sometimes reveal intransitive collective preferences. Suppose, for example, that the voting behavior of three citizens of a small society reveals that they each have transitive preferences over three alternatives:

a ![]() 1 b

1 b ![]() 1 c,

1 c,

b ![]() 2 c

2 c ![]() 2 a,

2 a,

c ![]() 3 a

3 a ![]() 3 b.

3 b.

Then b wins a vote between a and b, c wins a vote between b and c, and a wins a vote between c and a. The collective preference so revealed is intransitive:

a ![]() b

b ![]() c

c ![]() a.

a.

In real life, voting is often strategic. For example, Alice may agree to vote with Bob on one issue if he will vote with her on another. Modern politics would founder altogether without such log-rolling agreements. But those of us who enjoy paradoxes need have no fear of being deprived of entertainment. Game theory teaches us that the conditions under which some version of the Condorcet paradox survives are very broad. However, the kind of welfarism we consider in this chapter assumes that stable societies can somehow manage to evade these difficulties.

4.1.2 Plato’s Republic?

Ken Arrow (1963) generalized Condorcet’s paradox from voting to a whole class of aggregation functions that map the individual preferences of the citizens to a communal preference. Arrow’s paradox is sometimes said to entail that only dictatorial societies can be rational, but it represents no threat to utilitarianism because Arrow’s assumptions exclude the kind of interpersonal comparison that lies at the heart of the utilitarian enterprise.

A dictatorial society in Arrow’s sense is a society in which one citizen’s personal preferences are always fully satisfied no matter what everyone else may prefer. The fact that utilitarian collective decisions are transitive makes it possible to think of utilitarian societies as being dictatorial as well, but the sense in which they are dictatorial differs from Arrow’s, because the dictator isn’t necessarily one of the citizens. He is an invented philosopher-king whose preferences are obtained by aggregating the individual preferences of the whole body of citizens. In orthodox welfare economics, the philosopher-king is taken to be a benign government whose internal dissensions have been abstracted away.

The imaginary philosopher-king of the welfarist approach is sometimes called an ideal observer or an impartial spectator in the philosophical literature, but the stronger kind of welfarism we are talking about requires that he play a more active role. Obedience must somehow be enforced on citizens who are reluctant to honor the compromises built into his welfare-maximizing choices.

Critics of utilitarianism enjoy inventing stories that cast doubt on this final assumption. For example, nine missionaries can escape the clutches of cannibals if they hand over a tenth missionary whose contribution to their mission is least important. The tenth missionary is unlikely to be enthusiastic about being sacrificed for the good of the community, but utilitarianism takes for granted that any protest he makes may be legitimately suppressed.

Authors who see utilitarianism as a system of personal morality tend to fudge this enforcement issue. For example, John Harsanyi (1977) tells us that citizens are morally committed to honor utilitarian decisions. John Rawls (1972) is implacably hostile to utilitarianism, but he too says that citizens have a natural duty to honor his version of egalitarianism. But what is a moral commitment or a natural duty? Why do they compel obedience? We get no answer, either from Harsanyi or from any of the other scholars who take this line.

My own view is that traditional utilitarianism only makes proper sense when it is offered, as in welfare economics, as a set of principles for a government to follow (Goodin 1995; Hardin 1988). The government then serves as a real enforcement agency that can effectively sanction “such actions as are prejudicial to the interests of others” (Mill 1962). However, just as it was important when discussing the rationality of individuals not to get hung up on the details of how the brain works, so we will lose our way if we allow ourselves to be distracted from considering the substantive rationality of collective decisions by such matters as the method of enforcement a society uses. It is enough for what will be said about utilitarianism that a society can somehow enforce the dictates of an imaginary philosopher-king.

Pandora’s box? This last point perhaps needs some reinforcement. When we reverse the implicit causal relationships in traditional discussions by adopting a revealed-preference approach, we lose the capacity to discuss how a society works at the nuts-and-bolts level. What sustains the constitution? Who taxes whom? Who is entitled to what? How are deviants sanctioned? Such empirical questions are shut away in a black box while we direct our attention at the substantive rationality of the collective decisions we observe the society making.1

There is no suggestion that the social dynamics which cause a society to make one collective decision rather than another are somehow less important because we have closed the lid on them for the moment. As philosophers might say, to focus on consequences for a while is not to favor consequentialism over deontology. If we find a society—real or hypothetical—that acts as though it were maximizing a particular welfare function, the box will need to be opened to find out what social mechanisms are hidden inside that allow it to operate in this way. However, we are still entitled to feel pleased that temporarily closing our eyes to procedural issues creates a world so simple that we might reasonably hope to make sense of it.

4.2 Traditional Approaches to Utilitarianism

David Hume is sometimes said to have been the first utilitarian. He may perhaps have been the first author to model individuals as maximizers of utility, but utilitarianism is a doctrine that models a whole society as maximizing the sum of utilities of every citizen. This is why Bentham adopted the phrase “the greatest good for the greatest number” as the slogan for his pathbreaking utilitarian theory.

What counts as good? Bentham’s attitude to this question was entirely empirical. The same goes for modern Benthamites who seek to harness neuroscience to the task of finding out what makes people happy (Layard 2005). Amartya Sen (1992, 1999) is no utilitarian, but his proposal to measure individual welfare in terms of human capabilities might also be said to be Benthamite in its determination to find measurable correlates of the factors that improve people’s lives.

Bentham probably wouldn’t have approved of a second branch that has grown from the tree he planted, because it takes for granted the existence of a metaphysical concept of the Good that we are morally bound to respect. John Harsanyi (1953, 1955) originated what I see as the leading twig on this metaphysical branch of utilitarianism. John Broome (1991), Peter Hammond (1988, 1992), and John Weymark (1991) are excellent references to the large literature that has since sprung into being.

John Harsanyi. I think that Harsanyi has a strong claim to be regarded as the true prophet of utilitarianism. Like many creative people, his early life was anything but peaceful. As a Jew in Hungary, he escaped disaster by the skin of his teeth not once, but twice. Having evaded the death camps of the Nazis, he crossed illegally into Austria with his wife to escape persecution by the Communists who followed. And once in the West, he had to build his career again from scratch, beginning with a factory job in Australia. It took a long time for economists to appreciate his originality, but he was finally awarded a Nobel prize shortly before his death. Moral philosophers are often unaware that he ever existed.

Harsanyi’s failure to make much of an impression on moral philosophy is partly attributable to his use of a smattering of mathematics, but he also made things hard for himself by offering two different defenses of utilitarianism that I call his teleological and nonteleological theories (Binmore 1998, appendix 2).

4.2.1 Teleological Utilitarianism

What is the Good? G. E. Moore (1988) famously argued that the concept is beyond definition, but we all somehow know what it is anyway. Harsanyi (1977) flew in the face of this wisdom by offering axioms that supposedly characterize the Good. My treatment bowdlerizes his approach, but I think it captures the essentials.

The first assumption is that the collective decisions made by a rational society will satisfy the Von Neumann and Morgenstern postulates. A society will therefore behave as though it is maximizing the expected value of a Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility function. In this respect, the society behaves as though it were a rational individual whom I call the philosopher-king.

The second assumption is that the Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility function U of the philosopher-king depends only on the choices that the citizens would make if they were Arrovian dictators. If the N citizens of the society are no less rational than their philosopher-king, they will also behave as though maximizing the expected value of their own individual Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility functions un (n = 1, 2, . . . , N). We then need to know precisely how the philosopher-king’s utility function depends on the utility functions of the citizens.

To keep things simple, I suppose that ![]() is a social state that everybody agrees is worse than anything that will ever need to be considered, and

is a social state that everybody agrees is worse than anything that will ever need to be considered, and ![]() is a social state that everyone agrees is better. We can use these extremal states to anchor everybody’s utility scales so that U(

is a social state that everyone agrees is better. We can use these extremal states to anchor everybody’s utility scales so that U(![]() ) = un(

) = un(![]() ) = 0 and U(

) = 0 and U(![]() ) = un(

) = un(![]() ) = 1. For each lottery L whose prizes are possible social states, we then assume that

) = 1. For each lottery L whose prizes are possible social states, we then assume that

![]()

so that the philosopher-king’s expected utility for a lottery depends only on the citizens’ expected utilities for the lottery.2 The linearity of the expected utility functions then forces the function W to be linear (Binmore 1994, p. 281). But linear functions on finite-dimensional spaces necessarily have a representation of the form

![]()

If we assume that the philosopher-king will always improve the lot of any individual if nobody else suffers thereby, then the constants wn (n = 1, 2, . . . , N) will all be nonnegative.

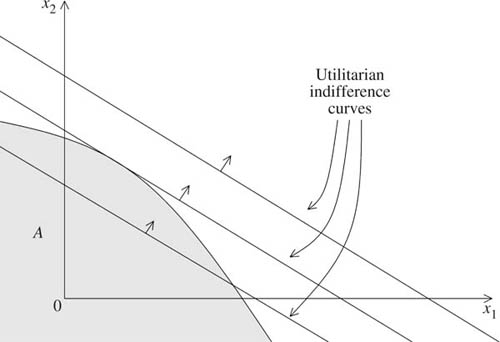

Formula (4.1) is the definition of a utilitarian welfare function. The constants w1, w2, . . . , wN that weight each citizen’s individual utility determine the standard of interpersonal comparison built into the system. For example, if w3 = 2w5, then each util of citizen 3 is counted as being worth twice as much as each util of citizen 5. Figure 4.1 illustrates how the weighting influences the choices a utilitarian society will make from a given feasible set.

Harsanyi not a Benthamite? Amartya Sen (1976) argued that Harsanyi shouldn’t be regarded as a utilitarian because he interprets utility in the sense of Von Neumann and Morgenstern. The criticism would be more justly directed at me for insisting on reinterpreting Harsanyi’s work in terms of revealed-preference theory.

Harsanyi himself is innocent of the radicalism Sen attributes to him. Although he borrows the apparatus of modern utility theory, Harsanyi retains the Benthamite idea that utility causes our behavior. Where he genuinely differs from Sen is in having no truck with paternalism. Harsanyi’s philosopher-king doesn’t give people what is good for them whether they like it or not. He tries to give them what they like, whether it is good for them or not.

Figure 4.1. Utilitarian indifference curves. The diagram shows the indifference curves of the utilitarian welfare function W(x1, x2) = x1 + 2x2. The indifference curves are parallel straight lines for much the same reason that the same is true in figure 3.13. The point of tangency of an indifference curve to the boundary of the feasible set A is the outcome that maximizes welfare. If we were to increase player 2’s weight from w2 = 2 to w2 = 3, her payoff would increase.

4.3 Intensity of Preference

When is it true that u(b) − u(a) > u(c) − u(d) implies that a person with the Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility function u would choose to swap b for a rather than c for d? Luce and Raiffa (1957) include the claim that Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility functions automatically admit such an interpretation in their list of common fallacies. But we have to be careful not to read too much into what Luce and Raiffa say.

It is true that nothing in the Von Neumann and Morgenstern postulates allows any deductions to be made about intensities of preference, because no assumptions about such intensities are built into the postulates. However, nothing prevents our making additional assumptions about intensities and following up the implications.

The intensity issue is especially important in a welfare context. The literature commonly assumes that most people have decreasing marginal utility: that each extra dollar assigned to Pandora is worth less to her than the previous dollar (section 3.3). But utilitarians don’t want the same to be true of utils. They want each extra util that is assigned to Pandora to be worth the same to her as the previous util.

Von Neumann and Morgenstern’s (1944, p. 18) take on the issue goes like this. Pandora reveals the preferences a ![]() b and c

b and c ![]() d. We deem her to hold the first preference more intensely than the second if and only if she would always be willing to swap a lottery L in which the prizes a and d each occur with probability

d. We deem her to hold the first preference more intensely than the second if and only if she would always be willing to swap a lottery L in which the prizes a and d each occur with probability ![]() for a lottery M in which the prizes b and c each occur with probability

for a lottery M in which the prizes b and c each occur with probability ![]() .

.

To see why Von Neumann and Morgenstern offer this definition of intensity, imagine that Pandora has a lottery ticket N that yields the prizes b and d with equal probabilities. Would she now rather exchange b for a in N, or d for c? Our intuition is that she would prefer the latter swap if and only if she thinks that b is a greater improvement on a than c is on d. But to say that she prefers the second of the two proposed exchanges to the first is to say that she prefers M to L.

In terms of Pandora’s Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility function u, the fact that L ![]() M reduces to the proposition

M reduces to the proposition

![]()

So Pandora holds the preference a ![]() b more intensely than the preference c

b more intensely than the preference c ![]() d if and only if u(b) − u(a) > u(d) − u(c).

d if and only if u(b) − u(a) > u(d) − u(c).

To evaluate the implications of Von Neumann and Morgenstern’s definition of an intensity of preference, suppose that u(b) = u(a) + 1 and u(d) = u(c) + 1. Then Pandora gains 1 util in moving from a to b. She also gains 1 util in moving from c to d. Both these utils are equally valuable to her because she holds the preference a ![]() b with the same intensity as she holds the preference c

b with the same intensity as she holds the preference c ![]() d.

d.

4.4 Interpersonal Comparison of Utility

The main reason that Lionel Robbins (1938) and his contemporaries opposed the idea of cardinal utility is that they believed that to propose that utility could be cardinal was to claim that the utils of different people could be objectively compared (section 1.7). But who is to say that two people who respond similarly when put in similar positions are experiencing the same level of pleasure or pain in the privacy of their own minds? Since neuroscience hasn’t yet reached a position where it might offer a reasonable answer, the question remains completely open.

Nor does it seem to help to pass from the Benthamite conception of utility as pleasure or pain to the theory of Von Neumann and Morgenstern. Attributing Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility functions to individuals doesn’t automatically allow us to make interpersonal comparisons of utility. The claim that it does is perhaps the most important of the fallacies listed in Luce and Raiffa’s (1957) excellent book. It is therefore unsurprising that economics graduate students are still often taught that interpersonal comparison of utility is intrinsically meaningless—especially since they can then be tricked into accepting the pernicious doctrine that outcomes are socially optimal if and only if they are Pareto-efficient.3

Von Neumann and Morgenstern (1944) clearly didn’t think that interpersonal comparisons of utility are necessarily meaningless, since the portion of their Theory of Games and Economic Behavior devoted to cooperative game theory assumes not only that utils can be compared across individuals, but that utils can actually be transferred from one individual to another. The notion of transferable utility goes too far for me, since only physical objects can be physically passed from one person to another. However, as in the case of intensity of preferences, nothing prevents our adding extra assumptions to the Von Neumann and Morgenstern rationality postulates in order to make interpersonal comparisons meaningful.

In Harsanyi’s teleological argument, the extra assumptions are those that characterize the choice behavior of a society, so that we can envisage it as being ruled by an all-powerful philosopher-king whose preferences are obtained by aggregating the preferences of his subjects. The standard of interpersonal comparison in the society is then determined by the personal inclinations of this imaginary philosopher-king from which we derive the weights in equation (4.1).

Where do the weights come from? According to revealed-preference theory, we estimate the weights by observing the collective choices we see a utilitarian society making. If its choices are stable and consistent, we can then use the estimated weights to predict future collective choices the society may make.

However, Harsanyi (1977) adopts a more utopian approach. He is dissatisfied with the idea that the standard of interpersonal comparison might be determined on paternalistic grounds that unjustly favor some individuals at the expense of others. He therefore requires that the philosopher-king be one of the citizens. The impartiality of a citizen elevated to the position of philosopher-king is guaranteed by having him make decisions as though behind a veil of ignorance. The veil of ignorance conceals his identity so that he must make decisions on the assumption that it is equally likely that he might turn out be any one of the citizens on whose behalf he is acting.4

Whether or not such an approach to social justice seems reasonable, the method by which Harsanyi copes with the problem of interpersonal comparison within his theory is well worth some attention.

Anchoring points. A temperature scale is determined by two anchoring points, which are usually taken to be the boiling point and the freezing point of water under certain conditions. Two anchoring points are also necessary to fix the zero and the unit on a Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility scale. In section 4.2, we took everybody’s anchoring points to be ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

It is sometimes argued that the mere choice of such common anchoring points solves the problem of interpersonal comparison. It is true that such a choice determines what counts as a util for each citizen. A society can therefore choose to trade off each util so defined against any other util at an equal rate. The weights in the utilitarian welfare function of (4.1) will then satisfy

w1 = w2 = . . . = wN.

The theory that results is called zero–one utilitarianism because the standard of interpersonal comparison is determined entirely by our decision to assign utility scales that set everybody’s zero and one at ![]() and

and ![]() . But what use is a standard chosen for no good reason? Who would want to use the zero–one standard if

. But what use is a standard chosen for no good reason? Who would want to use the zero–one standard if ![]() and

and ![]() meant that someone was to be picked at random to win or lose ten dollars when Adam is a billionaire and Eve is a beggar?

meant that someone was to be picked at random to win or lose ten dollars when Adam is a billionaire and Eve is a beggar?

But the shortcomings of zero–one utilitarianism shouldn’t be allowed to obscure the fact that comparing utils across individuals can be reduced to choosing anchoring points for each citizen’s utility scale. To be more precise, suppose that citizen n reveals the preference ![]() n

n ![]() n

n ![]() n. Then

n. Then ![]() n and

n and ![]() n will serve as the zero and the unit points for a new utility scale for that citizen. The Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility function that corresponds to the new scale is given by

n will serve as the zero and the unit points for a new utility scale for that citizen. The Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility function that corresponds to the new scale is given by

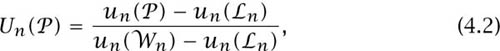

where un is the citizen’s old Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility function and Un is the citizen’s new Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility function.

We can now create a standard of interpersonal comparison by decreeing that each citizen is to be assigned a weight to be used in comparing the utils on his or her new scale with those of other citizens. If we assign Alice a weight of 5 and Bob a weight of 4, then 4 utils on Alice’s new scale are deemed to be worth the same as 5 utils on Bob’s new scale.

Such a criterion depends on how the new anchoring points are chosen, but it doesn’t restrict us to using the new utility scales. For example, reverting to Alice’s old utility scale may require replacing her new Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility function U by u = 2U + 3. We must then accept that 8 utils on Alice’s old scale are to be deemed to be worth the same as 5 utils on Bob’s new scale.

Such mathematical reasoning tells us something about the structure of any standard of interpersonal comparison of utility, but it can’t tell us anything substantive about whether some particular standard makes sense in a particular context. We need some empirical input for this purpose. For example, how do people in a particular society feel about being rich or poor? How do they regard the sick and the lame? In his nonteleological argument for utilitarianism, Harsanyi followed David Hume and Adam Smith in looking to our capacity to empathize with others for input on such questions.

4.4.1 Empathetic Preferences

If Quentin’s welfare appears as an argument in Pandora’s utility function, psychologists say that she sympathizes with him. For example, a mother commonly cares more for her baby’s welfare than for her own. Lovers are sometimes no less unselfish. Even Milton Friedman apparently derived a warm glow from giving a small fraction of his income to relieve the distress of strangers in faraway places. Such sympathetic preferences, however attenuated, need to be distinguished from the empathetic preferences to be discussed next.5

Pandora empathizes with Quentin when she puts herself in his position to see things from his point of view. Autism in children often becomes evident because they commonly lack this talent. Only after observing how their handicap prevents their operating successfully in a social context does it become obvious to what a large degree the rest of us depend on our capacity for empathy.

Pandora expresses an empathetic preference if she says that she would rather be Quentin enjoying a quiet cup of coffee than Rupert living it up with a bottle of champagne. Or she might say that she would like to swap places with Sally, whose eyes are an enviable shade of blue.

To hold an empathetic preference, you need to empathize with what others want, but you may not sympathize with them at all. For example, we seldom sympathize with those we envy, but Alice can’t envy Bob without comparing their relative positions. However, for Alice to envy Bob, it isn’t enough for her to imagine having Bob’s possessions and her own preferences. Even if she is poor and he is rich, she won’t envy him if he is suffering from incurable clinical depression. She literally wouldn’t swap places with him for a million dollars. When she compares her lot with his, she needs to imagine how it would be to have both his possessions and his preferences. Her judgment on whether or not to envy Bob after empathizing with his full situation will be said to reveal an empathetic preference on her part.

Modeling empathetic preferences. In modeling the empathetic preferences that Pandora reveals, we retain as much of the apparatus from previous chapters as we can. In particular, the set of outcomes to be considered is lott(X), which is the set of all lotteries over a set X of prizes. We write L ![]() M when talking about the personal preferences revealed by Pandora’s choice behavior. We write (L,

M when talking about the personal preferences revealed by Pandora’s choice behavior. We write (L, ![]() )

) ![]() (M, m) when talking about Pandora’s empathetic preferences. Such a relation registers that Pandora has revealed that she would rather be citizen m facing lottery M than citizen

(M, m) when talking about Pandora’s empathetic preferences. Such a relation registers that Pandora has revealed that she would rather be citizen m facing lottery M than citizen ![]() facing lottery L.

facing lottery L.

Harsanyi appends two simple assumptions about Pandora’s empathetic preferences to those of Von Neumann and Morgenstern.

Postulate 5. Empathetic preference relations satisfy all the Von Neumann and Morgenstern postulates.

Pandora’s empathetic preference relation can therefore be represented by a Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility function v that assigns a utility of

vn(![]() ) = v(

) = v(![]() , n)

, n)

to the event that she finds herself in the role of citizen n facing situation ![]() .

.

Harsanyi motivates the next postulate by asking how Pandora will decide to whom she should give a hard-to-get opera ticket that she can’t use herself. One consideration that matters is whether Alice or Bob will enjoy the performance more. If Bob prefers Wagner to Mozart, then the final postulate insists that Pandora will choose Wagner over Mozart when making judgments on Bob’s behalf, even though she herself may share my distaste for Wagner. No paternalism at all is therefore allowed to intrude into Harsanyi’s system.

Postulate 6. Pandora is fully successful in empathizing with other citizens. When she puts herself in Quentin’s shoes, she accepts that if she were him, she would make the same personal choices as he would.

The postulate is very strong. For example, it takes for granted that Pandora knows enough about the citizens in her society to be able to summarize their choice behavior using personal Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility functions. When attempts to agree on what is fair in real life go awry, it must often be because this assumption fails to apply.

In precise terms, postulate 6 says that if un is a Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility function that represents citizen n’s personal preferences, and v is a Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility function that represents Pandora’s empathetic preferences, then ![]() vn represents the same preference relation on lott (X) as

vn represents the same preference relation on lott (X) as ![]() un.

un.

It is convenient to rescale citizen n’s Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility by replacing un by Un, as defined by (4.2). We then have that Un(![]() n) = 0 and Un (

n) = 0 and Un (![]() n) = 1. We can choose any utility scale to represent Pandora’s empathetic preferences, provided we don’t later forget which anchoring points we chose to use.

n) = 1. We can choose any utility scale to represent Pandora’s empathetic preferences, provided we don’t later forget which anchoring points we chose to use.

Two Von Neumann and Morgenstern utility functions that represent the same preferences over lott (X) are strictly increasing affine transformations of each other (section 3.6). So we can find constants an > 0 and bn such that

![]()

for any prize ![]() in X. We can work out an and bn by substituting

in X. We can work out an and bn by substituting ![]() n and

n and ![]() n for

n for ![]() in (4.3) and then solving the resulting simultaneous equations. We find that

in (4.3) and then solving the resulting simultaneous equations. We find that

The answers we get depend on Pandora’s empathetic utilities at citizen n’s anchoring points, because it is her empathetic preferences that we are using to determine a standard of interpersonal comparison of utility.6

We now propel Pandora into the role of a philosopher-king behind Harsanyi’s veil of ignorance. Which lottery L will she choose from whatever feasible set she faces? If she believes that she will end up occupying the role of citizen n with probability pn, she will choose as though maximizing her expected utility:

![]()

where the constant term p1b1 + p1b1 + . . . + p1b1 has been suppressed because its value makes no difference to Pandora’s choice. If we write xn = ![]() Un (L), we find that Pandora then acts as though maximizing the utilitarian welfare function of (4.1) in which the weights are given by

Un (L), we find that Pandora then acts as though maximizing the utilitarian welfare function of (4.1) in which the weights are given by

wn = pnan.

In summary: when Pandora makes impartial choices on behalf of others, she can be seen as revealing a set of empathetic preferences. With Harsanyi’s assumptions, these empathetic preferences can be summarized by stating the rates at which she trades off one citizen’s utils against another’s.

The Harsanyi doctrine. The preceding discussion avoids any appeal to what has become known as the Harsanyi doctrine, which says that rational people put into identical situations will necessarily make the same decisions.

In Harsanyi’s (1977) full nonteleological argument, all citizens are envisaged as bargaining over the collective choices of their society behind a veil of ignorance that conceals their identities during the negotiation. This is precisely the situation envisaged in Rawls’s (1972) original position, which is the key concept of his famous Theory of Justice. Harsanyi collapses the bargaining problem into a one-person decision problem with a metaphysical trick. Behind his veil of ignorance, the citizens forget even the empathetic preferences they have in real life. They are therefore said to construct them anew. The Harsanyi doctrine is then invoked to ensure that they all end up with the same empathetic preferences. So their collective decisions can be delegated to just one of their number, whom I called Pandora in the preceding discussion of empathetic preferences.

Harsanyi’s argument violates Aesop’s principle at a primitive level. If you could choose your preferences, they wouldn’t be preferences but actions! However, Rawls is far more iconoclastic in his determination to avoid the utilitarian conclusion to which Harsanyi is led. He abandons orthodox decision theory altogether, arguing instead for using the maximin criterion in the original position (section 3.7).

My own contribution to this debate is to draw attention to the relevance of the enforcement issue briefly mentioned in section 4.1. If one gives up the idea that something called “natural duty” enforces hypothetical deals made in the original position, one can use game theory to defend a version of Rawls’s egalitarian theory (Binmore 1994, 1998, 2005). My position on the debate between Harsanyi and Rawls about rational bargaining in the original position is therefore that Harsanyi was the better analyst but Rawls had the better intuition.

1 The rationality of this book is sometimes called substantive rationality to emphasize that it is evaluated only in terms of consequences. One is then free to talk of procedural rationality when discussing the way that decisions get made.

2 I avoid much hassle here by assuming directly a result that other authors usually derive from what they see as more primitive axioms.

3 An outcome is Pareto-efficient if nobody can be made better off without making somebody else worse off. For example, it is Pareto-efficient to leave the poor to starve, because subsidizing them by taxing the rich makes rich people worse off.

4 Moral philosophers will recognize a version of John Rawls’s (1972) original position, which Harsanyi (1955) independently invented.

5 Economists traditionally follow the philosopher Patrick Suppes (1966) in referring to empathetic preferences as extended sympathy preferences.

6 It makes no effective difference if we replace v by Av + B, where A > 0 and B are constants.